Choosing the Price: How Leaders Pay for War

3 Mar 2014

By Rosella Cappella for ISN

One of the most important decisions a leader can make is how to pay for a country’s war effort. In an era when states are facing ballooning deficits, economic austerity, and increased financial globalization, understanding war finance is more important than ever. How a state finances a war has implications for the conduct of the war, the economic health of the state (debt accumulation, inflation, and the redistribution of wealth), democratic accountability, and leadership survival. Thus, as economies contract and states cut deficit spending to balance their budgets, the source of war finance is at the forefront of contemporary debates regarding future economic growth, political stability, and national security.

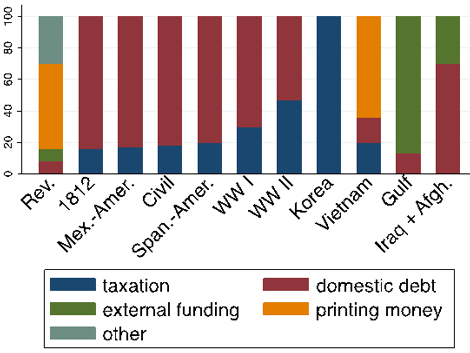

Unfortunately, war finance is often discussed as a tax-versus-borrow tradeoff, and the policy chosen is explained via a war’s cost. That is, costlier wars are paid for by higher amounts of debt. Neither of the two claims can explain why the United States chose to finance 50% of World War II—its most expensive war to date, with a whopping price tag of 35.8% of GDP in 1945—by taxation. Nor does it explain why the United States chose to finance its recent war efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, two of the cheapest wars it has fought (a mere 1.2% of GDP in 2008, the costliest year of the war), entirely by domestic and foreign debt (See Figure 1).[1]

Figure 1. Variation in U.S. War Finance[2]

So, what policy options do leaders have beyond tax and debt? What then, if not the cost of war, explains leaders’ decision making when deciding how to finance a war?

What Are States Paying For?

The narrow concept of cost, the budgetary cost of the war, is the direct financial outlay to pursue military objectives. This narrower conception excludes many pertinent expenses as well as human costs in life and suffering. Excluded are pre-war armament programs, demobilization, occupation, and arms races. Also excluded are indirect costs to society such as veterans’ costs, the effect of loss of life on a state’s economy, or interest payments on war debt. While a broader conceptualization of cost may be useful for long-term analyses of the consequences of war, the focus of state leaders themselves is procuring money for specific military operations within a specific theater and for a specific duration. War finance, therefore, is the means by which the state meets the costs of executing the war effort. It is the manner by which the state redirects or procures monetary resources to meet government outlays to continue the war.

War Finance Options

How can a state finance a war? What options are available to policymakers? The majority of wars are financed though some combination of taxation, domestic debt, money printing, and funding from abroad. Each war finance alternative has distinct political and economic costs and benefits.

Taxation is the most politically costly method of war finance as it directly wrests income from citizens. On the other hand, it is the least costly economically as it combats inflation by removing purchasing power from citizens, lowering the demand for scarce goods, and reducing pressure on prices.

Domestic borrowing, money lent to the government from individuals, groups, or institutions within the country with the explicit understanding that it will be paid back over time, compounds the cost of war through high interest rates and has inflationary effects by increasing the money supply. It is less politically costly, however, as it only asks for money from citizens.

External funding refers to resources from abroad that can be used to achieve domestic objectives. These include securities floated on foreign markets, inter-state loans, grants, or even plunder. External funding is less politically costly than taxation and domestic debt as the state does not ask anything from domestic society. However, it is relatively more economically costly than domestic debt and taxation. External funding can be inflationary as it increases the money supply while not removing purchasing power from citizens.

Unlike taxation and domestic debt printing does not use money already circulating within the state. Thus, the initial political cost of printing is low—the government pays for the war effort without demanding anything from society. By contrast, the economic costs of printing are enormous and can result in disastrous inflation.

Leadership Decision Making

Ultimately, leaders must choose either the economic or political price of conflict via their war finance choice. They can’t have their cake and eat it too. This means that leaders base their war finance decision on their desire to stay in power, their desire to avoid economic ruin, and their desire to win the war.

Because leaders want to stay in power, they want to take the least politically costly war finance option. Political cost is contingent on public support for the war. Low public support for the war, in turn, raises the political cost of extracting tax revenue from a reluctant society. As a result, leaders’ preferences move away from a war financed by taxation to a war finance strategy that asks as little as possible from its citizens, i.e. domestic borrowing, external funding, or printing. Conversely, high support in favor of the war reduces the political cost of extracting tax revenues, making it a more likely war finance option.

Leaders also prefer to avoid economic ruin. How a state finances its war effort can mitigate (taxation) or compound (debt and printing) the effect of war inflation. Thus, when inflation is on the horizon, leaders will choose to finance a war via taxation. Conversely, when inflation is not a concern, leaders will choose the least politically costly options such as printing, domestic debt, or external war finance. During President Truman’s financing of the Korean War, for example, both the fear of inflation and public support for the war was high. As soon as the war started so did inflation. Between June and December 1950, the consumer price index increased by 47%, while the index of wholesale prices rose by 10.4%. [3] President Truman immediately petitioned Congress for a war tax for the explicit purpose of combatting inflation. At the same time, high public support for the war made it easier for Congress to acquiesce to the president’s request. The result was unprecedented—a costly war financed entirely through taxation.

Not all leaders, however, have the freedom to exercise the full array of war finance options. A leader may favor taxation for its anti-inflationary effects and debt avoidance. However, if the state does not have the capacity to extract tax revenue, the leader will not be able to exercise that option. Not all is lost however. Low tax-capacity states often engage in long wars. The Mexican war effort during the Mexican-American War (1846–1848) is one such example. An already weak revenue administration was further weakened by the war. The state could not depend on its normal sources of revenue as ports were blockaded and a vast portion of the country was overrun. Thus, the state turned to other sources of war finance. The state borrowed from the church, borrowed from the British, and plundered. In sum, if leaders are committed to the war effort, even if they are unable to raise taxes, they will finance the war by other means.

Leaders also have no choice but to engage in external war finance when their states have to purchase inputs from abroad and do not have the currency to do so. The starkest example of this scenario is the British during World War II. When it came to financing the domestic aspect of World War II, the British government was cost-effective. The country raised taxes to keep inflation down, borrowed cheaply at a set rate of 3%, and borrowed progressively with a bond campaign that reached the entire population. Nonetheless, they had to rely heavily on costly external war finance to pay for many inputs for the war effort that were purchased from abroad, specifically the United States. Without the currency to pay for these goods, a dollar bankrupt British government engaged in a costly loan from the United States in the form of Lend-Lease aid.

The Future of War Finance

The current trend of war finance suggests a preoccupation with political over economic costs. As various countries are facing economic downturns, inflation is unlikely to be a great concern. Thus, leaders are likely to choose less politically costly options—taxation and borrowing at home and abroad—to finance their war efforts. Consequently, societies will be one step further removed from their country’s war effort. In addition, as the world becomes more integrated, external funding will also come to the fore. That is, as countries are purchasing more and more inputs for their military hardware from abroad, they will need the foreign currency to do so.

Regardless of patterns in economic growth or sources of war inputs, the bottom line is that leaders choose the price of war. They can choose to pay a political price or an economic price. They can’t mitigate both.

[1] Daggett, S. (2010). Costs of Major U.S. Wars. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service.

[2] For United States’ financing of the War of 1812 to the Korean War, see Paul Studentski and Herman Kross’ Financial History of the United States (1952). For U.S. financing of the Vietnam War, see Tom Riddell, A Political Economy of the American War in Indo-China: Its Costs and Consequences (1975). For Gulf War finance, see United States Congressional Report (Conduct of the Persian Gulf War: Appendix P, 1992). In the Revolutionary War column, “other” is referring to plunder and the selling of land for money.

[3] The Economic and Political Hazards of an Inflationary Defense Economy , 1951, p. 5.