Rapprochement on the Korean Peninsula

8 Mar 2019

By Linda Maduz for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published in the CSS Analyses in Security Series by the Center for Security Studies on 6 March 2019. This article is also available in German and French.

When it comes to the Korean peninsula, the spotlight is on the summits between the US president, Donald Trump, and the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-un. However, the impetus for the current rapprochement initiative arose from developments at the inter-Korean level. Without the participation of the incumbent South Korean government, the ongoing détente in the nuclear dispute would hardly be imaginable. For South Korea, much is at stake. The aim of the current diplomatic initiative is not just to contain its northern neighbor’s nuclear ambitions, but also to help bring a modicum of predictability to the often erratic inter-Korean relations and facilitate long-term détente on the peninsula. This is especially important, and even becomes a life-and-death matter, when considered against the background of the isolationist and self-interested withdrawal of the US as the protecting power.

The Korean conflict today is marked by a new set of geopolitical determinants. It is true that the security order in East Asia remains largely shaped by the bilateral agreements that the US concluded after the Second World War with its Asian allies. The latter received security guarantees and access to the US market. In return, the US secured a military presence and important alliance partnerships in Asia. Subsequently, the foreign and security policies of East Asian countries, namely South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, would be closely aligned with those of their protector, the US. Today, this arrangement is in jeopardy, due to the end of the East-West confrontation, a resurgent China that wields more and more economic and political clout in the region, and domestic developments on both sides of the Pacific (i.e. democratization, diminishing internationalism).

North Korea’s newly acquired military capabilities are also contributing to realignments of power and interests. In 2017, North Korea tested long-range missiles that are theoretically capable of delivering nuclear warheads to major US cities. Therefore, the strategic stance of the US must now also take into account the possibility of a direct nuclear threat by North Korea. Given North Korea’s de facto nuclearization, the question of how an overarching political strategy towards North Korea should be shaped and which role the broadly coordinated international sanctions should play in such a strategy appears more urgent than ever. North Korea’s immediate neighbors, in particular, want to avoid the twin dangers inherent in the current sanctions regime – a humanitarian disaster and regime collapse. In view of the shifting framework conditions, it remains to be seen how North Korea will behave in the near future and whether the close security policy alliance between the US and South Korea will endure.

Politics in North Korea

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the beginning of North Korea’s enduring international isolation, which has lasted to this day. The Cold War dynamics had not only brought about the separation of the two Koreas in the war of 1950 – 1953, but also shaped the subsequent divergent developments of the two sibling states. For North Korea, which was integrated into the Soviet bloc, the end of the East-West conflict also marked the end of the strong diplomatic and economic support it had been given by the Soviet Union and China, leading to a collapse of its external trade structures. North Korea’s difficulties in realigning itself politically and economically were due not least to ideological issues. Both the extreme isolation and the exceptional stability of the world’s most autocratic state (according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s EIU Democracy Index 2017) were fostered by the socialist state ideology of juche. Introduced by the state’s founder, Kim Il-sung, it has secured the Kim dynasty’s legitimacy over three generations and given rise to a cult of personality around the leadership. The ideology, which upholds the supreme maxim of securing the country’s political and economic independence, manifests itself in a philosophy of economic autarky and extreme militarism.

Today, North Korea is highly dependent on China, not least as a result of sanctions imposed on Pyongyang in the course of the nuclear dispute. Ninety per cent of North Korea’s foreign trade is currently conducted with China. The UN Security Council’s (UNSC) sanctions regime has stopped up to 90 per cent of North Korean exports. The first round of sanctions was imposed in response to North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006, the second in response to the second nuclear test in 2009. In doing so, the UNSC demanded that North Korea return to the Nuclear Weapons Test Ban Treaty and that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) resume inspections. With the new round of sanctions imposed in 2016 and 2017, the UNSC is now targeting the entire spectrum of North Korea’s economy. The effectiveness of these sanctions is dramatically enhanced as countries like China have begun to enforce them more systematically in recent years (presumably in response to the secondary sanctions imposed by the US in 2017). Accordingly, one of North Korea’s immediate negotiation objectives is to have these sanctions loosened.

In 2011, the current North Korean leader Kim Jong-un succeeded his late father Kim Jong-Il. Under Kim Jong-un’s leadership, North Korea accelerated the pace of its nuclear weapons program and has stepped up parallel efforts to advance the country’s economic development (byungjin strategy, 2013). Four out of its six nuclear tests and more than 80 missile tests have taken place since 2011. At the end of 2017, Kim Jong-un announced that the nuclear missile program had been successfully concluded, and in early 2018, he announced mass production of nuclear warheads and ballistic missiles. North Korea, he claimed, was now sufficiently powerful to deter the US with nuclear arms. Having reached this goal, it appears that the North Korean leadership has shifted its focus toward the development of the national economy. Since 2013, several hundred new markets have been licensed as complements to informal markets. The latter came into existence during the great North Korean famines of the 1990s and are increasingly tolerated under Kim Jong-un’s watch. Reportedly, such free-market activities account for a large part of the national GDP today. As a nuclear power, the regime now finds itself with a strong hand in the talks, while its economic ambitions lead it to pursue new aims and interests in negotiations.

Politics in South Korea

In recent decades, good relations with the US have been the bedrock and the foundation of South Korea’s rapid political and economic development. While the country’s economic development had been comparable to that of North Korea as recently as the 1970s, the resource-poor developing country rapidly advanced to become the world’s eleventh largest economy. During the 1980s, the former military dictatorship underwent a democratization process. Today, it is considered the most democratic country in Asia (EIU Democracy Index 2017). Militarily and strategically, the US remains South Korea’s most important partner and an indispensible ally. Currently, 28,500 US troops are stationed in South Korea. To this day, Seoul remains in the crosshairs of tens of thousands of North Korean artillery pieces and short-range missiles that are capable of delivering biological, chemical, and nuclear payloads. While the military equipment, some of which dates back to the 1950s, is regarded by experts as obsolete, North Korea still has the world’s fourth-largest army, according to a 2015 report by the US Department of Defense. Out of its population of 25 million, 1.2 million are in active military service. South Korea, with twice the population, has only half as many military personnel.

South Korea’s policy vis-à-vis North Korea is marked by party politics. The two main political camps advocate two different approaches for resolving the conflict while ensuring the continued existence of South Korea and a long-term order for peaceful coexistence on the Korean peninsula. The conservative camp places a premium on national security, including the security alliance with the US, and favors adopting a hard line vis-à-vis Pyongyang. The progressive camp supports good direct relations with North Korea and views the presence of US forces in South Korea with skepticism. In 1998, the progressive camp managed for the first time to win the presidency, electing former opposition politician Kim Dae-jun as head of state. This marked the beginning of the “Sunshine Policy” towards North Korea that was continued over two presidential terms until 2008. It encompassed an active and essentially unconditional policy of cooperation with North Korea, including investment and economic aid from the South to the North. Cross-border economic and cultural projects, such as the Kaesong Industrial Region or the tourism project at Mount Kumgang, were shut down again during the subsequent conservative presidencies of Lee Myung-bak (2008 – 2013) and Park Geun-hye (2013 – 2017) as intra-Korean relations deteriorated.

South Korea’s current President Moon Jae-in took office in May 2017 and prioritized rapprochement with North Korea from the very beginning. To understand the importance that he ascribes to intra-Korean relations, one should not only look to his membership in the progressive camp, but also consider his personal history: Long ago, Moon’s parents fled from the North to South Korea. The human rights attorney, who was once an active supporter of the democracy movement in his youth, was one of the main advisors and a close friend of former president Roh Moo-hyun (2003 – 2008). One the one hand, Moon remains true to the stance of his progressive predecessors by seeking good relations and actively promoting confidence-building measures between the two Korean states. On the other hand, he has adopted elements of the strategy pursued by his conservative predecessors, who demanded that the nuclear dispute be resolved as a precondition for improved relations and trade-offs. Specifically, the South Korean government under Moon’s leadership demands that the sanctions regime should only be loosened once North Korea makes concrete steps towards denuclearization.

The Current Convergence of Interests

Kim Jong-un’s New Year speech at the beginning of 2018 marked the official start of the current process of rapprochement. On this occasion, and in subsequent statements, the North Korean leader indicated his willingness to engage in intra-Korean talks and meetings. However, South Korea under President Moon had spent months in preparation for this diplomatic overture. This included informal meetings between government representatives. The platform of the Winter Olympics in South Korea was skillfully leveraged to resume the intra- Korean dialog. Later, South Korea mediated between North Korean and US actors at critical junctures, ensuring that the diplomatic process could be continued and the summit between Kim and Trump could take place in mid-2018.

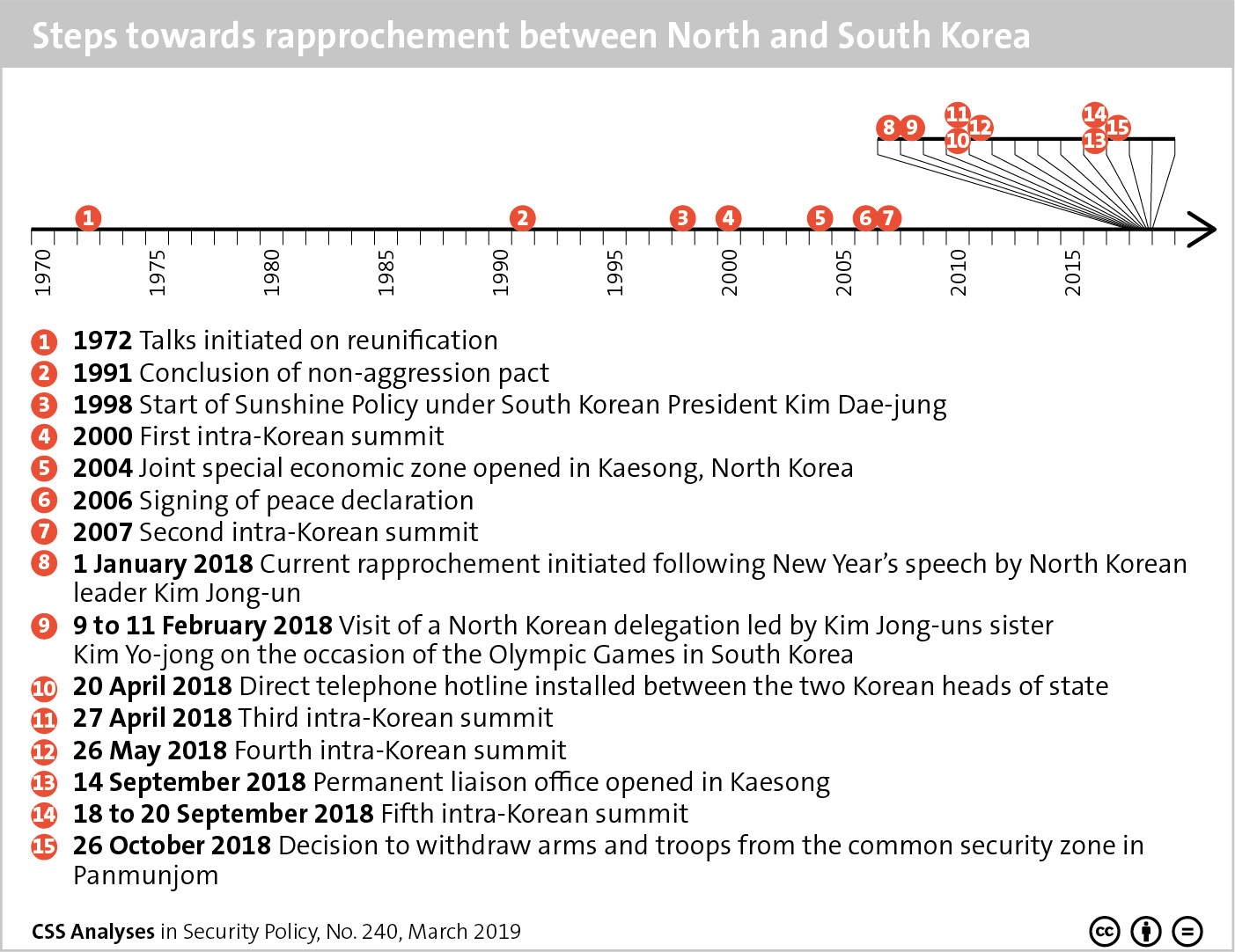

The year 2018 was a historic one for the history of the Korean conflict. Overall, the South Korean president and the North Korean leader met three times, including one memorable encounter on the southern side of the border village of Panmunjom. Important confidence-building measures were initiated with the aim of opening channels of communication between the two Koreas (see Figure). At the international level, the first US-North Korean summit ever was held in June 2018, constituting the high point of rapprochement. In order to avoid negative reactions by their respective counterparts on the other side, the US and South Korea decided in the course of 2018 to forgo their annual joint military exercises, while North Korea waived further nuclear and missile tests. Despite the less than succesfull second US-North Korean summit at the end of February 2019, the parties are sticking to these peace-building measures.

South Korea’s current policy towards the North reflects the political stance of President Moon Jae-in. More generally, however, it might also indicate a fundamental strategic shift against the background of simultaneous changes in US-South Korean relations. Should the US prove to be a less reliable protecting power in the future, the result in South Korea might be the emergence of a hitherto lacking cross-party consensus on relations with the North that prioritizes direct intra-Korean relations. According to Moon, intra-Korean relations should be primarily shaped by the two Korean states themselves. The denuclearization of North Korea, which is the focus of international efforts vis-à-vis North Korea, is also one of South Korea’s key demands. However, for South Korea, it is only one of several disparate elements required for realizing its overarching goal: An order that avoids military tensions and ensures long-term peace and stability on the peninsula.

The Moon government has now succeeded in launching a policy of détente on the Korean peninsula. This is all the more remarkable when considering the policy of threats and pressure that the Trump administration pursued until early 2018. However, this aggressive US stance also shows that the steps taken by South Korea are necessary for avoiding dangerous escalation and ultimately the risk of war. The North Korean regime has actively reciprocated the South Korean diplomatic offensive. Its cooperative behavior should be seen in the context of its newly acquired negotiation options.

North Korea’s current interests and options in dealing with South Korea and other parties to the conflict are not only determined by its technical capabilities as a de-facto nuclear power, but also by two strategic realignments. It is safe to assume that North Korea will cling to its nuclear weapons as a means of securing power and rule. However, in addition to the safety of the regime, it is increasingly the country’s economic development that is referenced as a priority and as a pillar of the regime’s survival. Accordingly, in Kim Jong-un’s New Year speeches of 2018 and 2019, the matter was given due prominence. Another recent change in intra-Korean relations is that North Korea no longer regards the South as a US puppet, but as a direct interlocutor. In order to achieve its short-term and longer-term economic interests, North Korea needs international partners. In this context, South Korea is important, but so are China and Russia.

Due to various long- and short-term developments, the interests of the two Korean states are currently converging. As a result, cooperative efforts are currently prevailing in intra-Korean relations. A look at the long history of the Korean conflict shows that cooperation can rapidly deteriorate into confrontation. Successful periods of rapprochement (see Figure) were repeatedly interrupted and reversed. Among the critical moments were the attempted assassination of the South Korean president (1983) or the sinking of a South Korean warship (2010), with North Korea standing accused as the perpetrator on both occasions. Thus, even the current moves towards reconciliation are essentially all reversible. Why, therefore, should or could things be different this time?

Switzerland and the Korean Conflict

Since 1953, Switzerland has a security policy mandate to maintain a presence on the Korean peninsula. It is a member of the UN Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission, which was originally in charge of monitoring troop and armaments levels. Switzerland’s mandate on the southern side of the demarcation line is shared with Sweden. On the northern side, Poland and the former Czechoslovakia shared responsibility for this task until being expelled in 1995 and 1993, respectively. The mission on the intra-Korean border was the Swiss armed forces’ first peace support operation. Today, of the 96 staff that were stationed there initially, only five Swiss officers remain in the Demilitarized Zone.

Switzerland has good relations with both Korean states, with whom it maintains diplomatic relations and conducts regular political consultations. While Switzerland supports the UN sanctions regime against North Korea, it has declined to impose additional sanctions, unlike the EU. In 1997, Switzerland opened a cooperation office of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (DEZA) in Pyongyang, facilitating good access to a country that is otherwise notoriously unapproachable. Since 2012, the office has focused exclusively on humanitarian aid. In recent years, Switzerland has also intensified its relations with South Korea, particularly in the areas of business and research.

With its local expertise and its good relations with the parties to the conflict, Switzerland would be well positioned to take on a potential mediating role in any future peace process or to support preliminary confidence-building measures. It has already provided its Good Offices in the past: Geneva has hosted meetings between the two Koreas, the US, and China (Four-Party Talks, 1997 – 1999), as well as between the US and North Korea (three meetings during the Six-Party Talks, 2003 – 2009).

New Opportunities, Old Obstacles

The intra-Korean rapprochement has attained a dynamic of its own that is currently shaking up the crisis surrounding North Korea’s nuclear program. While this move towards détente creates opportunities for new bilateral solutions, its limitations are just as apparent. The intra-Korean sphere of the conflict is too closely interwoven with the international level, and the interests of all parties involved in the conflict are too complex and interrelated. Ultimately, a lasting resolution of the Korean conflict requires that the nuclear issue be resolved, which in turn would determine the future of sanctions against North Korea. For further steps towards intra-Korean rapprochement, such as the deepening of economic relations or a continuation of the summit diplomacy on South Korean soil, the two Koreas depend on an easing of sanctions and thus on the material consent of the US. Consequently, the question of intensifying cooperation between North and South Korea will not be decided by the Koreans alone.

One key international determinant in the nuclear dispute has been the stance adopted by the US administration of the day. While Trump threatened North Korea with total annihilation as recently as 2017, today he relies on diplomacy. It was also Trump who had previously cast doubt on the continued presence of US troops in South Korea and the establishment of a US missile defense system, due to the high cost involved for the US. Even though such unpredictable behavior and unilateral actions have introduced uncertainty to the security alliance with South Korea, they have also opened up new avenues for (partial) solutions concerning North Korea. The current US government – probably for lack of alternatives – is casting aside earlier, internationally agreed approaches as adopted during the Six-Party Talks (2003 – 2009), while also admitting the possibility of departing in substance from the previously non-negotiable demand for full, verifiable, and irrevocable denuclearization of North Korea. While a more flexible US strategy has the potential to create more leeway for North Korea to play off the various parties to the conflict against each other, it would also open up the prospect of taking into account North Korea’s newfound interest in its (market) economy, as well as its current diplomatic openness.

The current opportunities for progress in the Korean conflict are also due to the stance adopted by the South Korean government under Moon Jae-in. Moon’s cooperative policy towards North Korea enjoys popular support, as reflected, for instance, in the success of his party at the 2018 local elections. However, his term in office ends in 2022. It is not inconceivable that, given the current geopolitical constellation, a conservative government would once more raise the option of building up a nuclear deterrent capability of its own. Moreover, surveys show that the younger generation of South Koreans is no longer as positively disposed toward rapprochement or the possibility of reunification with North Korea. Rather, South Korean 20-year-olds tend to view North Korea as a hostile or foreign nation. If the momentum of the current diplomatic process can be leveraged to pave the way for new solutions in the Korean conflict, or at least to make the attempt, that would be the most desirable outcome for all parties involved.

Recent Issues in the CSS Analyses in Security Policy Series

- More Continuity than Change in the Congo No. 239

- Military Technology: The Realities of Imitation No. 238

- The OSCE’s Military Pillar: The Swiss FSC Chairmanship No. 237

- Long-distance Relationships: African Peacekeeping No. 236

- Trusting Technology: Smart Protection for Smart Cities No. 235

- The Transformation of European Armaments Policies No. 234

About the Author

Linda Maduz is Senior Researcher in the Global Security Team at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich. She is the author of “Flexibility by design: The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the future of Eurasian cooperation”, among other publications.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.