Involved in the Middle East: George W Bush versus Barack Obama

29 Jun 2017

By Aneta Hlavsová for Central European Journal of International and Security Studies (CEJISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made in Volume 11, Issue 2 of the external pageCentral European Journal of International and Security Studies (CEJISS)call_made.

This article evaluates the different foreign policy approaches of the United States Administration under the 43rd and 44th presidents, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, towards the Middle East. They each projected a completely different style of conflict resolution strategy. While George Bush is known as “war president,” Obama utilised a Wilsonian approach in his foreign policy attitudes, especially towards the countries of the Middle East. While in office, Obama managed to overcome the neorealist legacy of George Bush, to arrange a ground-breaking nuclear non-proliferation deal with Iran, to (at least partly) withdraw US troops from Iraq as well as Afghanistan, and to carry out the “new” Middle East military engagements in line with international laws or general support. This paper studies how Obama’s new foreign policy approach shifted some of the international and regional paradigms in terms of balance of power in the Middle East.

United States Foreign Policy

This article evaluates the different foreign policy approaches of two US presidents towards the Middle East. George W. Bush and Barack Obama each relied on different foreign policy mechanisms and forms of leadership, and while the former became to be known as a “war president” pursuing unilateralist and illegitimate or illegal military interventions in other countries, the latter projected a more multilateralist approach to international relations, gaining international support for his engagements in the Middle East.

Nonetheless, it is debatable whether the two presidents’ foreign policy differs as to means and consequences. Therefore, this paper examines the decisions of two of the US leaders Administrations concerning Middle Eastern countries and societies and determines whether (and how) their different foreign policy approaches altered the balance of power within the region.

Methodologically, the paper chronologically follows the relevant foreign policy decisions of George W. Bush and Barack Obama in order to compare and evaluate the different aspects of their military engagements in the Middle East. Concerning sources and literature, the paper builds on the main speeches and proclamations given by the two presidents as well as the National Security Strategy documents which frame the respective presidential doctrines.

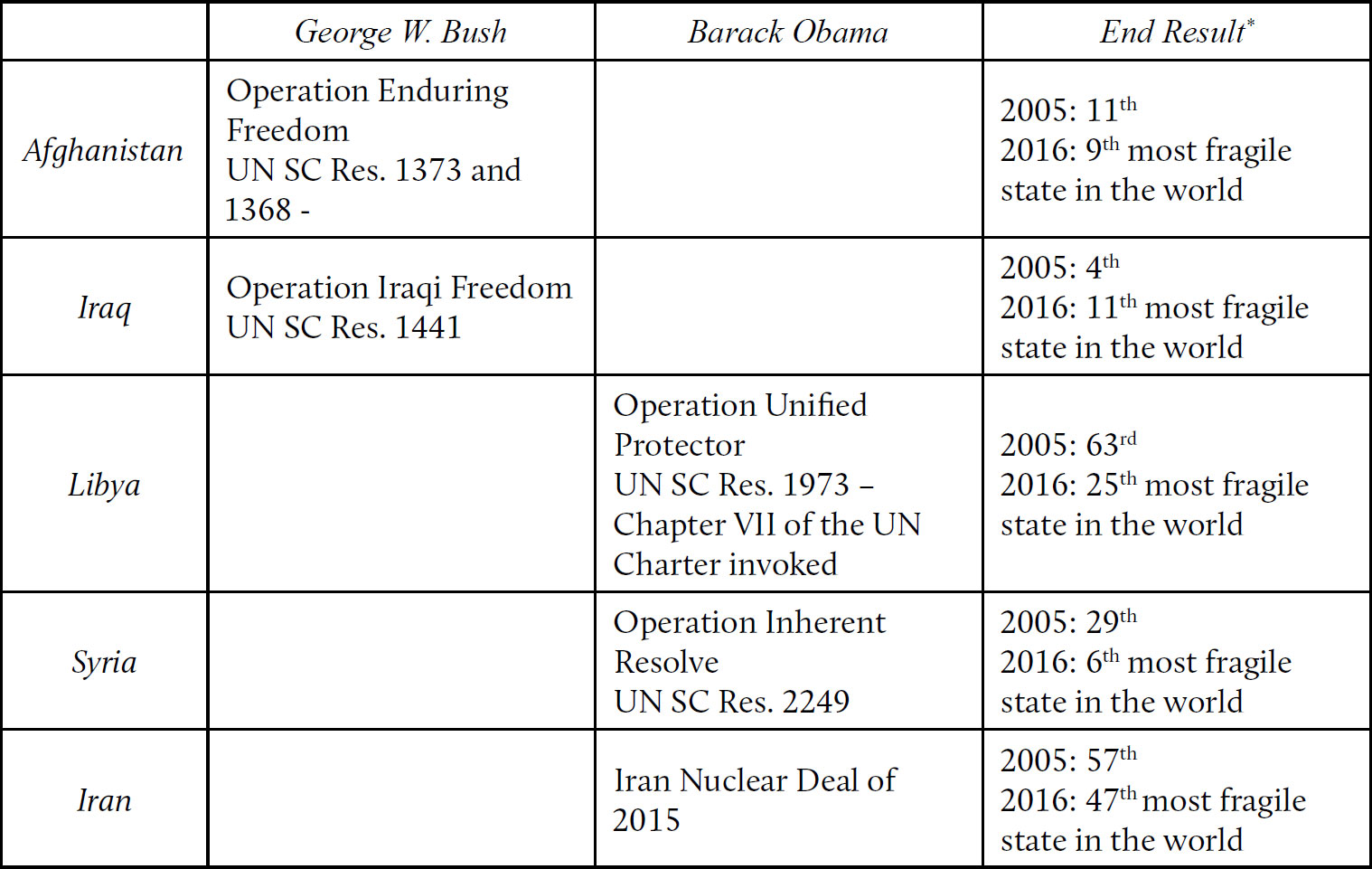

The first part deals with the military interventions carried out by the Bush administration, that is, the US decisions to go to wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; the second part then follows the foreign policy of Barack Obama and his interventions in Libya and Syria. The executive summary provides a table summarizing US foreign policy towards the Middle East over the course of the past fifteen years, linking the other countries of the region into the overall balance of power system.

Military Interventions Under Bush

Researching the different foreign policy approaches of George W. Bush and Barack Obama, specifically the US foreign policy towards the Middle East from 2001 until the autumn of 2016, one may come across a problem inherent in the internal political system of the United States – the bipartisan mind-set of the American political scene. In reality, the discourse often transforms into a Democrat – Republican stand-off when Democrats fiercely criticize Bush for his foreign policy actions and subsequently the Republicans criticize Obama for his security strategy; additionally, when there were what initially appeared as sparks of democracy in the Middle East in the form of the Arab Spring in 2010-2011, voices attempted to vindicate Bush and claim he was right about his foreign policy decisions all along. For instance, Greenwald1 asserted in 2011, speaking of the successes of the Bush administration in the Middle East, their fight against terrorism and the already-ongoing Arab Spring, that it ‘was the Freedom Agenda of the George W. Bush administration—delineated and formulated as a conscious alternative to jihadism—that showed the way’ to other Arab societies. In other words, in order to correctly evaluate the different foreign policies of presidents’ Bush and Obama, it is necessary to remain detached and look at the matter through a non-partisan lens.

Bush’s First Term in Office and the post 9/11 Foreign Policy Shift

The horrific terrorist attacks of 9/11 quickly changed the course of Bush’s presidency. However, it is debatable whether he would have become war-prone in his foreign policy attitudes if it had not been for the 2001 events. In retrospect, Bush’s foreign policy priorities before the attacks included the country’s relationship with Russia and China and building a ballistic missile defence system around the world. Concerning the Middle East, Bush’s attention was aimed at the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and whether a ‘peace settlement was in the cards.’2 Therefore, originally, not much attention was to be attributed to the Middle East; nonetheless, this was promptly reconsidered following September 11, 2001.

Swiftly getting involved in Afghanistan, Bush in his January 2002 State of the Union Address heavily praised his own success in the country’s regime change and exclaimed, rather prematurely, that thanks to the skills of the US troops and American military might, “we are winning the war on terror.”3 Bush, in that same speech, also delineated the infamous axis of evil countries consisting of North Korea, Iraq, and Iran – a perilous legacy which Barack Obama diligently tried to overcome. It is also of some interest that Bush in this flagship address did not mention Saudi Arabia at all – obstinately taking Saudi Arabia as a US ally in the Middle East. The speech links the 9/11 attacks to Afghanistan (and by extent to Iraq) only, leaving Saudi Arabia and its possible connections to terrorism for the next president to address.

Nonetheless, the ensuing 2002 National Security Strategy document, published in September, left little to the imagination as to what was coming. As part of the already-commenced war on terror, the Strategy (along with the already ongoing invasion of Afghanistan) virtually paved the road towards the Iraq operation: ‘While the United States will constantly strive to enlist the support of the international community, we will not hesitate to act alone, if necessary, to exercise our right of self-defence by acting pre-emptively against such terrorists, to prevent them from doing harm against our people and our country.’4 Put differently, within the first two years of Bush’s first presidential term, the US had already been militarily involved in Afghanistan as well as in Iraq, all the while offering the American public a strong rhetoric against Iran.

Additionally, the legality of the two wars and the corresponding debate play an important role in the evaluation of Bush’s doctrine. Even though, again usually along the partisan lines in the US, there were people arguing for the legality of the operations, it should be noted that neither of the invasions received the appropriate mandate from the United Nations. In the case of Afghanistan, immediately following the 9/11 attacks, the Security Council passed two resolutions condemning the terrorist acts. Resolution 1368 expresses ‘its readiness to take all necessary steps to respond to the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, and to combat all forms of terrorism;’5 similarly, Resolution 1373 calls on states to combat terrorism and to cooperate in their fight6. Nonetheless, none of these documents specifically invoke UN Charter’s Chapter 7. The 2010 report for the British House of Commons states that if the US pursued the ‘all means necessary’ clause from the Security Council, they would have possibly obtained it; however, the existing resolutions ‘simply state the broad general requirement to take action to combat international terrorism.’7

Concerning the Iraqi operation, the unilateralist approach became even clearer. UN Security Council Resolution 1441 calls onto Iraq to cooperate with the international agencies concerning its weapons of mass destruction programs8; nonetheless, no resolution authorized the invasion per se. This is not to say that the current situation and instability in the Middle East is solely the fault of George W. Bush, owing to the fact that the roots of anti-Americanism in the region go much deeper into history. Ironically, pursuing unilateralist and interventionist policies in Afghanistan and Iraq deepened the Arab societies’ distrust in American behaviour abroad.

Bush’s Second Term in Office and the Perpetual War on Terror

In 2005, Bush’s second inaugural speech underlined the general cause of virtually all the evil in the world, proclaiming that ‘The survival of liberty in our land increasingly depends on the success of liberty in other lands,’9 swiftly linking the idealist promotion of democracy abroad to US national security and suggesting that only democracies will not promote terrorism and therefore it is high time to end all tyranny in the world. It is noteworthy that such democracy promotion was a shift from his previous rhetoric as it ‘became an effective rhetorical device for blunting domestic critics.’10 The National Security Strategy of 2006 then continued on a similar note, praising the democratising effects of the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq;11 while at the same time it reminded the general public that there still exist states in the Middle East that do not comply with American worldviews, such as Syria and Iran, which “continue to harbour terrorists at home and sponsor terrorist activity abroad.”12

As a summary of George W. Bush’s two-term presidency, the White House offers an online list of the president’s achievements – and especially those concerning the Middle East are noteworthy, being labelled as Fact Sheet: President Bush’s Freedom Agenda Helped Protect the American People. Directly resulting from the president’s second inaugural address, the fact sheet states that Bush “has kept his pledge to strengthen democracy and promote peace around the world”13 further suggesting that he “acted quickly and decisively to help end international crises.”14 Concerning Iraq, the fact sheet posits that as a direct result of the allied invasion, the US “freed 25 million Iraqis from the rule of Saddam Hussein, a dictator who murdered his own people”15 – the overthrow of Saddam Hussein being indeed an undeniable fact.

Even up to this day, the fact sheet continues to proclaim that the ‘U.S. and Iraqi forces have made significant progress in reducing sectarian violence, restoring basic security to Iraqi communities, and driving terrorists and illegal militias out of their safe havens’16 resulting in overall enhanced security which in turn paved the road for political and economic development. In general, the rest of the fact sheet speaks of Bush’s contributions to democracy in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Israel/Palestine.

Obama’s Twist on Bush’s Foreign Policy

What was the US legacy in the Middle East the newly elected president inherited in 2009? Two illegal (and costly) wars – one of them being completely illegitimate; an Arab society latently preparing for the unprecedented Arab Spring; Iran portrayed as part of the axis of evil countries; but a firm alliance with Israel and Saudi Arabia. Nonetheless, the promotion of democracy by the Bush administration in the Middle East was to manifest itself soon after the inauguration of president-elect Barack Obama.

A vast study conducted by Bruce Gilley on the topic of Bush’s democratization attempts in the Middle East provides interesting insights. Bill Clinton’s administration’s cap on democracy promotion spending in the Middle East was at $ 3 million annually; however, during the Bush era, specifically between 2006 and 2008, the US spending reached an astronomical $ 436 million,17 even excluding the spending on the Iraqi and Afghani wars. The author further posits that most of the money went to virtually 7 crucial countries – Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, and Yemen.18 Except for Pakistan, all the countries were to soon experience the Arab popular uprising of 2010-2011.

This is not to suggest that the Bush administration directly caused what came to be called the Arab Spring. The reasons for the Arab wave of protests against authoritarian governments run more deeply and complex than the simple US wish for a democratized Middle East. It is undeniable, however, that Bush pushed for the democratization of the region.

Obama’s First Term in Office and the Arab Spring

The succeeding president Barack Obama inherited a true conundrum. The United States’ economy was crippled by a severe financial and economic crisis, the country was heavily (and expensively) involved in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the overall situation in the Middle East was becoming increasingly labyrinthine. ‘Obama spent much of his first six months in office working to prevent the collapse of the US economy and with it the international financial system’19 and it became apparent to the new president that the Middle Eastern challenges were not to be resolved unilaterally. In fact, Obama proclaimed in The Atlantic interview that most importantly, having inherited the US foreign policy after George W. Bush, his task was not to do anything ‘stupid.’20 And indeed, the international developments were not particularly kind to Obama’s position.

In December 2010, the Arab countries in Northern Africa and the Middle East experienced mass uproars against their establishments. Most countries of the Arab world participated in the general wave of protest, including all seven of the countries where Bush’s freedom agenda was heavily supporting democratization through financial flow.21 At first, Obama was being quite hopeful as he ‘continued to speak optimistically about the future of the Middle East, coming as close as he ever would to embracing the so-called freedom agenda of George W. Bush, which was characterized in part by the belief that democratic values could be implanted in the Middle East.’22 However, the president quickly grew sceptical as the events were turning out to be more to the detriment of the countries involved when honest calls for democratizations gave way to brutality and different kinds of oppression. Goldberg then continues to write that ‘what sealed Obamas fatalistic view was the failure of his administrations intervention in Libya, in 2011.’23 This is where Obama should have learned the lesson from his predecessor.

Contrary to unilateralist decisions made by George W. Bush concerning interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, Obama managed to employ a more diplomatic and multilateral stance. In general, Obama’s foreign policy is described by neoliberals as multilateral, internationalist and/or Wilsonian. When Ikenberry differentiates between the two respective presidents, he notes that Obama ‘is more sceptical about the use of military force than the last President, but he is manifestly more internationalist in his embrace of the wider spectrum of partnerships, institutions, and diplomatic engagements that make up the American-led order.’24

Hence, concerning the Libyan crisis, the intervening coalition consisted of not only the US and NATO European states, but Middle Eastern parties as well (namely, Saudi Arabia and Jordan, Turkey as a NATO member), which granted the coalition even more credit. The United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 1973 with 5 abstentions (Germany, Brazil, China, Russia, and India) establishing a no-fly zone over Libya and allowing the coalition to take ‘all necessary measures’25 to protect the country’s civilian population. ‘Obama did not want to join the fight,’26 however, pressure from the British and the French along with factions within US internal politics forced him to join in.

The intervention could be considered a success in that it did prevent the anticipated massacres of civilian population in Benghazi. It also had a spillover effect when on 30 October 2011, the empowered (and enraged) opposition captured and (possibly unlawfully) killed Muammar Qaddafi. Nonetheless, the intervention proved to be the lowest point in Obama’s presidency – as he learned one lesson from Bush, but not the crucial one. The United States along with the coalition forces “planned the Libya operation carefully – and yet the country is still a disaster.”27 Obama criticized the British and the French prime ministers for their roles in the operation; however, according to The Guardian report, he admitted that ‘the biggest mistake of his presidency was the lack of planning for the aftermath of Muammar Gaddafi’s ouster in Libya that left the country spiralling into chaos and coming under threat from violent extremists.’28 And in the flagship Goldberg’s interview, Obama similarly acknowledged that the US prognosis of the tribal division of Libyan population was inadequate.

Unfortunately, Obama added to the list of US foreign policy failures a repeated pattern. Planning a military offensive, an invasion, or an operation carefully and then swiftly seeing it through is undeniably a fantastic quality of the Americans. However, planning for what comes next (after a regime is overthrown or an operation is finished) and actually understanding the Middle East is what the United States repeatedly failed to do. Due to these grave mistakes, three out of the three countries where the US (along with the coalition forces) intervened are in complete turmoil now, that in turn calls for a serious attention of the international community – the most obvious example being the ISIS threat to peace and security and balance of power in the entire region.

Obama’s Second Term in Office and the “War on Terror”

Similarly to Bush who whose presidency was challenged by the traumatic and unprecedented 9/11 attacks, Obama observed a rebirth of terrorism in the Middle East in the form of the now notoriously-infamous Islamic state. Even though the beginnings of this organization are linked directly to the war in Iraq and the coalition’s behaviour in the region (Gerges writes that the many detention camps and US-run prisons in Iraq clearly served as incubators of future Islamic fundamentalists and radicals, since for instance ‘former detainees compare Camp Bucca to an “Al Qaeda school,” an institution that produced jihadists in a factory-like environment,’29 and the Islamic state per se was first proclaimed on 13 October 2006), its biggest success came only in 2014, already under Obama’s watch, when it swept through vast regions of Iraq and Syria gaining significant portions of the two countries in which to proclaim their Islamic state. In retrospect, the US involvement in Syria and Iraq under the umbrella of a fight against terrorism was nothing short of a chaotic foreign policy filled with the pursuit of many old-time national interests. Firstly, Obama’s intervention in Syria was troubled, to say the least, even before there was any actual involvement. Tragically, and ironically enough, the Americans had been calling for the removal of Bashar al-Assad even before the Syrian people had the same objective in mind – dating back to Bush’s suggestion that Syria was harbouring terrorists, combined with the fact that Assad’s regime has strong ties with Putin’s Russia. The United States wanted to oust the Syrian president Bashar al-Assad (since a general blueprint for democratization of the Middle Eastern countries is to remove its authoritarian leaders and then ‘hope for the best’). However, the first wave of popular protests in Syria had a different shape – the original protestors were calling for genuine economic and legislative reforms as years of neo-liberal economic reforms gravely damaged the agrarian sector and produced strata of poor, disengaged, and unemployed people.30 These people started to call for new economic opportunities, not the removal of Assad. Nonetheless, with the ensuing brutal governmental crackdown on the protesters, the range of their demands consequently broadened.

After months of pressure from the Republican and the hawkish- Democratic camps in Washington, Obama drew the adversarial ‘red line’ for Assad concerning the regime’s chemical weapons program in August 2012.31 Nonetheless, Obama then failed to gain congressional support for a military intervention, and hence, the red line was never enforced by the United States. Ironically, ‘a deus ex machina appeared in the form of the Russian president, Vladimir Putin’32 when the Russians subsequently secured the removal of chemical weapons from the Syrian war-torn country. This may have been the last point at which the national interests of the United States and Russia did somewhat converge concerning the security situation in Syria.

The year 2014 complicated the entire Middle East geopolitical scene at large. Nonetheless, it wasn’t only due to Islamic state’s vast successes which marked 2014 as fierce. It was also the Crimean crisis and the Russian annexation of the peninsula which has shaped the uneasy US-Russia relations until today. Unfortunately, as the relations between the two countries deteriorated, the fight against terrorism, which should have been carried out as a joint effort of the international community became focused on the pursuit of different national objectives rather than a collective victory over Islamist jihadism.

Put differently, despite the initial rapprochement between the US and Russia at the beginning of Obama’s first term (in the form of a New START treaty signed in 2010), the two countries’ mutual relationship disintegrated after the Crimean annexation in 2014. Their relation turned into black and white Cold War logic, which negatively influenced their combined stand against the Islamic state in Syria and Iraq. The United States, already displeased with the annexation of Crimea and the re-election of Bashar al-Assad for the third time, became more upset when the Russian forces became directly involved in Syria in the autumn of 2015 (at the request of the Syrian government). The decision of Russians to join the fight against militant Islamic fundamentalism has been widely debated. Russia has a large Muslim minority and has dealt with fundamentalists in the past; therefore, Putin rightly feared the spread of Islamist radicalization further north from the Middle East. Unfortunately, what should have been a joint effort of the US and Russia to combat terrorism turned into a petty ‘you-did-it-no-you-did-it’ nihilist standoff between Obama and Putin.

On the other hand, 2015 represented the biggest shift in a positive direction in the US-Iranian relations. The two countries’ mutual relations were strained, to say the least, for the better part of a half of century – culminating in Bush adding Iran to the axis of evil countries in 2002. Nonetheless, the goodwill of Barack Obama led to great results in this case because he “had assumed that if the United States moderated its tone, reached out to foreign capitals, stressed common interests and then decided to lead, others would follow.”33 And luckily enough, quite a number of European countries, including Germany and France, followed.

The permanent members of the Security Council (the US, the UK, France, Russia, and China) plus Germany finally struck a deal34 with Iran on 14 July 2015. As revolutionary as this American-Persian rapprochement was, it further complicated the already complex relations within the region. Iran’s fundamental foes, Israel and Saudi Arabia, were particularly not pleased with the developments. However, Obama was determined to see this historical deal to its end. He suggests that Iran as well as Saudi Arabia need to acknowledge the new Middle Eastern dynamics, and that ‘they need to find an effective way to share the neighbourhood and institute some sort of cold peace.’35 The Saudi-Obama relations were nonetheless complicated from the very onset of his presidency (long before any Iran deal negotiations started to take shape) as Obama was soon portraying himself to be much less likely than his predecessor to side with the Arabian ally: ‘They had never trusted Obama—he had, long before he became president, referred to them as a “so-called ally” of the U.S.’36 And Obama has been indeed clearly unenthusiastic about the US-Saudi alliance as well.

The Fragile State Index, as developed annually ever since 2005 by the Fund for Peace Washington-based think tank, puts the US foreign policy towards the Middle East in a new perspective. It has been demonstrated that the behaviours of George W. Bush and Barack Obama in the international arena were different – up to a certain degree.

The military operations aimed at combating terrorism in the Middle East under the Bush administration were unilateralist actions. They did not receive the ‘all means necessary’ clause from the United Nations Security Council, nor did Bush ‘win the war on terror.’ In fact, the actions of the coalition forces were an additional factor in the creation of a new wave of Islamist jihadists, this time under the umbrella of the so-called Islamic state. Additionally, after going into Iraq under false pretences, Bush must have changed the overall rhetoric during his second term in office – ‘democracy promotion’ in selected countries became the bread and butter of the US foreign policy decision making and public rhetoric.

On the other hand, the Libyan military intervention was both a legal and a legitimate action of the international community as Obama and the coalition forces first received the appropriate mandate from the United Nations Security Council. In the case of the Syrian bombing operation, the question of legality was discussed as well – even though the UN SC Resolution 2249 had been passed unanimously under Chapter VII of the UN Charter calling on the member states to combat the Islamic state, the ‘all means necessary’ clause was technically still absent from that resolution. Nonetheless, there seems to be a consensus among the international community ‘that US strikes against ISIL in Syria are probably illegal but widely recognised as legitimate.’37

Hence, the 44th president of the United States partly managed to learn an important lesson from his predecessor. However, in terms of the well-being of the states involved, Obama did not learn the most crucial one – that is, regardless of the legality of the operations, all the countries of the Middle East where the United States became militarily engaged during the past 15 years are currently worse off.

Receiving the appropriate mandate from the Security Council and gaining support of the international community are indispensable for a new-age military doctrine of any world leader. However, in reality, this does not matter much to the people physically involved. Libya is still a “mess” – overthrowing a regime by a coalition force is “easy,” unlike the post-involvement reconstruction of the state which no one paid attention to. As a direct result of this fatal omission, the country is currently in complete disarray; and so are Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria.

Additionally, concluding the nuclear deal with Iran seems to have altered the regional balance of power even further. Obama’s natural distrust in the Saudis and his not-so-fundamentalist support of the Israelis allowed the United States, along with the countries of the Security Council plus Germany, to negotiate a ground-breaking treaty with a long-time foe of the international system. Possibly, this could mean for the future that Iran may have a strengthened position for the bid for regional hegemony as opposed to Saudi Arabia, which is tragically involved in its own military operation in neighbouring Yemen. Iran could use this diplomatic success and ease its isolationism within the region.

Conclusion

The paper has attempted to study the different foreign policy approaches of George W. Bush and Barack Obama towards countries of the Middle East. Particularly, it scrutinized the Bush’s administration involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq – which were two illegal wars with vast negative consequences for the security of the region. Further, it examined the foreign policy of Barack Obama towards Libya and then his combat against terrorism in Syria and Iraq with relation to his approach to Russian engagement in Crimea and Syria.

As a result of the analysis, the paper has argued that due to gross mismanagement (and possibly grave misunderstanding of the Arab societies) of the post-conflict reconstruction of the states (namely, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya), the countries in which the United States, along with a coalition of their aides, militarily intervened during the past fifteen years are currently worse off than ever before.

Put differently, the three countries where the US openly intervened are in a state of chaos. Having compared the foreign policy measures taken by Bush and Obama, a shift in the US foreign policy is evident. Obama, contrarily to Bush, relied on the mechanisms of the United Nations and made sure – trying to learn the lesson that Bush did not, that the Libyan operation was a legal and a multilateral effort at the same time. However, in the end, Obama made exactly the same mistakes as his predecessor – he underestimated the complexities of Arab societies and failed to plan for ‘what comes next.’ Unfortunately, the end results for Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya are all quite similar.

It is the historic rapprochement with Iran which needs to be carried on. Obama managed to overcome the unilateralist legacy of George W. Bush and together with the international community signed a historic deal with this ‘rogue’ Middle Eastern country, a long-time open foe of the United States. It is still too early for us to tell if President Donald Trump will continue on this note. It is also this historic Iran Deal which may have the biggest opportunity in changing the regional balance of power, provided that Iran continues its diplomatic engagement with the international community and that the relationship between the United States and/or Saudi Arabia and Israel remains not-so-fundamentalist and questionable as they were under the Obama administration. Only then might there be enough space for Iranian political manoeuvring in its bid for a regional hegemonic presence.

Notes

1 Greenwald, A. (2011). What We Got Right in the War on Terror. Commentary Magazine. September 1, 2011. Available from: https://www.commentarymagazine.com/articles/what-we-got-right-in-the-war-on-terror/

2 Leffler, M. P. (2011). September 11 in Retrospect: George W. Bush’s Grand Strategy, Reconsidered. Foreign Affairs. September/October 2011. Available from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2011-08-19/september-11-retrospect

3 Bush, G. W. (2002). The President’s State of the Union Address. January 29, 2002. Washington, DC, The United States.

4 The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. (2002). The White House. September 17, 2002.

5 United Nations Security Council Resolution 1368. (2001). Security Council resolution 1386 (2001) on the situation in Afghanistan. December 20, 2001.S/RES/1386 (2001).

6 United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373. (2001). Threats to international peace and security caused by terrorist acts. September 28, 2001. S/RES/1373 (2001).

7 Smith, B., and A. Thorp. (2010). The Legal Basis for the Invasion of Afghanistan. International Affairs and Defence Section, House of Commons. February 26, 2010. SN/IA/5340.

8 United Nations Security Council Resolution 1441. (2002). The situation between Iraq and Kuwait. November 8, 2002. S/RES/1441 (2002).

9 Bush, G. W. (2005). President Bush’s Second Inaugural Address. January 20, 2005. Washington, DC, The United States.

10 Lindsay, J. M. (2011). George W. Bush, Barack Obama and the Future of US Global Leadership. International Affairs. 87(4), pp. 765 – 779.

11 The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. (2006). The White House. March 2006.

12 The National Security Strategy of the United States of America. (2006). The White House. March 2006. p. 9.

13 Fact Sheet: President Bush’s Freedom Agenda Helped Protect The American People. The White House. Available from: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/freedomagenda/

14 Fact Sheet: President Bush’s Freedom Agenda Helped Protect The American People. The White House. Available from: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/freedomagenda/

15 Fact Sheet: President Bush’s Freedom Agenda Helped Protect The American People. The White House. Available from: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/freedomagenda/

16 Fact Sheet: President Bush’s Freedom Agenda Helped Protect The American People. The White House. Available from: https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/infocus/freedomagenda/

17 Gilley, B. 2013. (2013). Did Bush Democratize the Middle East? The Effects of External–Internal Linkages. Political Science Quaterly. 128(4), pp. 653 – 685.

18 Gilley, B. 2013. (2013). Did Bush Democratize the Middle East? The Effects of External–Internal Linkages. Political Science Quaterly. 128(4), pp. 653 – 685.

19 Lindsay, J. M. (2011). George W. Bush, Barack Obama and the Future of US Global Leadership. International Affairs. 87(4), pp. 765 – 779.

20 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through his Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

21 Gilley, B. 2013. (2013). Did Bush Democratize the Middle East? The Effects of External–Internal Linkages. Political Science Quaterly. 128(4), pp. 653 – 685.

22 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

23 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

24 Ikenberry, J., G. (2014). Obama’s Pragmatic Internationalism. The American Interest. Available from: http://www.the-american-interest.com/2014/04/08/obamas-pragmatic-internationalism/

25 United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973. (2011). Libya. March 17, 2011. S/RES/1973 (2011).

26 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

27 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/

archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

28 Barack Obama Says Libya Was ‘Worst Mistake’ of His Presidency. (2016). The Guardian. April 12, 2016. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/apr/12/barack-obama-says-libya-was-worst-mistakeof-his-presidency

29 Gerges, F., A. (2016). ISIS: A History. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. Pg. 133.

30 Gerges, F., A. (2016). ISIS: A History. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. Pg. 172.

31 Ball, J. (2012). Obama Issues Syria a “Red Line’ Warning on Chemical Weapons. The Washington Post. August 20, 2012. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/obama-issues-syria-redline-warning-on-chemical-weapons/2012/08/20/ba5d26ec-eaf7-11e1-b811-09036bcb182b_story.html

32 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

33 Lindsay, J. M. (2011). George W. Bush, Barack Obama and the Future of US Global Leadership. International Affairs. 87(4), pp. 765 – 779.

34 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. (2015). July 14, 2015, Vienna.

35 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

36 Goldberg, J. (2016). The Obama Doctrine: The U.S. President Talks Through His Hardest Decisions about America’s Role in the World. The Atlantic. April 2016. Available from: http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2016/04/the-obama-doctrine/471525/

37 Farrell, T. (2014). Are the US-led Air Strikes in Syria Legal - and What Does it Mean if they are not?. The Telegraph. September 23, 2014. Available from: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/middleeast/syria/11116792/Are-the-US-led-air-strikes-in-Syria-legal-and-what-does-it-mean-if-theyare-not.html

About the Author

Aneta Hlavsová is a Ph.D. student at Jan Masaryk Centre of International Studies, Faculty of International Relations, University of Economics, Prague.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.