Criminal, Religious and Political Radicalisation in Prisons: Exploring the Cases of Romania, Russia and Pakistan, 1996-2016

30 Mar 2017

By Siarhei Bohdan and Gumer Isaev for Central European Journal of International and Security Studies (CEJISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCentral European Journal of International and Security Studies (CEJISS)call_made on 8 November 2016.

Abstract

Ironically, prison and imprisonment plays a significant in role in the development of radicalised and extremist individuals and movements—a point highlighted by the recent enquiry into the radicalisation process of Islamists in Europe. The fact that prison might act as a ‘school of crime’ is one of the most debated issues in the field of penology and has begun to impact decision making in the areas of judicial affairs, social work, policing and public policy more generally. The state penitentiary system is intended to correct and improve a person who committed a crime – driven by whatever ideology or without any ideology. However, sometimes, prison becomes the vehicle for criminal and radical ideological careers. This article presents an attempt to revisit and reapply some concepts of labelling theory, developed by sociologists, to analyse a succinct political science issue in terms of the relationship between penal systems and governance structures. This work questions what and how measures taken by state agencies to persecute law-breaking activities of various types may contribute to increases in these activities, their intensity and scale. This work deploys a comparative methodology and examines Romania (criminal), Russia (criminal/ ideological) and Pakistan (ideological) to gauge the level of radicalisation occurring in their prisons.

Introduction

Prison and imprisonment plays a significant in role in the development of radicalised and extremist individuals and movements—a point highlighted by the recent focus into the radicalisation process of Islamists in Europe. The fact that prison might act as a ‘school of crime’ is one of the most debated issues in the field of penology and has begun to impact decision making. The state penitentiary system is intended to correct and improve a person who committed a crime – driven by whatever ideology or without any ideology. However, sometimes, prison becomes the vehicle for criminal and radical ideological careers. This article revisits and reapplies some concepts of labelling theory, developed by sociologists, to analyse a succinct political science issue in terms of the relationship between penal systems and governance structures. This work questions what and how measures taken by state agencies to persecute law-breaking activities of various types may contribute to increases in these activities, their intensity and scale. This work deploys a comparative methodology and examines Romania (criminal), Russia (criminal/ideological) and Pakistan (ideological) to gauge the level of radicalisation occurring in their prisons.

That prisons can function as a breeding ground for organised criminal and extremist activities is nothing new and an assortment of powerful subcultures are known to have developed from within prison walls—such as the Russian blatnoi mir (criminal world) which is a self-sustaining community funded entirely through illegal activities. And it is not only criminality being fostered in prisons: they often incubate socio-political and religious extremist organisations. The cases of Sayid Qutb and Abu-Bakr Baghdadi are illustrative of the phenomenon.

And, prisons have been shown to act as a way of transference—of turning people from one type of deviant behaviour to another one. For instance, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (the de facto father of ISIS), began as an ordinary criminal and became a radical Islamist in prison. Transference is also reflected in levels of criminality. Both Romania and Russia – owing to their lack of adequate rehabilitation mechanisms – have seen the steady increase of repeat offenders that go on to commit more and more criminal acts. In short, prison is – in many places – the school for radicalism and criminality instead of detention for the sake of the punishing of offenders. Before delving deeper into this dynamic and exploring the comparative cases of Romania, Russia and Pakistan, it is important to provide an overview as to the theoretical foundations this work is built on and to tease out some of the deployed terminology.

Theoretical Framework

A common thread that stiches together organised criminal activities (Romania, Russia) and religious extremism (Pakistan) is the nature of the agent or perpetrator of certain, deviant and radicalised behaviours. It is therefore important to highlight that this work is, in fact, focused on how some penal systems encourage the very things they are meant to punish—deviancy and the requisite violations of law that act as a challenge to social order and norms. While, for this work we define both political extremism and criminality as, essentially, a single type of deviant behaviour even though – as will be discussed at length below – the reasons for such behaviours may differ. For instance, in Romania and Russia, the issue mostly gravitates around politically motivated neglect of corruption in the prison apparatus while in Pakistan it is closely connected to the infiltration of the penal system by those with overt or covert Islamist sympathies.

In short, this work considers the issue of radicalisation as involving a specific type of deviant behaviour regardless of its ideational grounds. Radicalisation means increasing readiness to challenge the social order and its norms or a readiness to undertake more “radical” acts which can be defined as more provocative, violent and wide-scale. But that also includes willingness to join and form appropriate structures and organisations (although in some cases that can be very general kind of membership or virtual interaction with networks). However, the most important aspect includes the willingness to directly challenge the social order.

This raises an important question about the driving forces behind deviance. Sociological studies on deviance long ago pointed out that the sources and causes of initial deviance may differ from the sources and causes of continuing deviance. Lemert, for instance, argued that the initial causes of individual deviance (including criminal behaviour) in many cases are different than those which determine its further continuation. He proposed to define them as primary and secondary deviance, correspondingly.1

Lemert insisted that primary deviance is “polygenic,” i.e., generated by numerous factors while the secondary is driven not by original causes but by the external reaction to the primary deviance. Secondary deviance reflects ‘how deviant acts are symbolically attached to persons and the effective consequences of such attachment for subsequent deviation on the part of that person.’2 Incarceration – in all its forms and types, i.e., before the trial and after it – may be considered the strongest type of that external response, and taking into custody in many cases labels a persons as a deviant with regard to existing social order. That creates premises for possible secondary deviance and, hence, radicalisation.

Conditions in jail – both treatment by administration, contacts with other prisoners or arrested, possibility of communications with outside world while in jail, etc. – significantly shape subsequent choice how to behave of a person after he or she is released from the prison. He or she can either choose to return to following the social order norms and conventions or the person can opt for further challenging these norms. And if the conditions in jail would facilitate the latter choice, then the jails become a place of radicalisation and part of the problem of deviance and not part of its solution.

So, one implication concerns the role of institutions in facilitating radicalisation. In other words, where ideologies (their content, basis or sophistication) are used to justify deviance by deviant persons to themselves or others, the level of radicalisation largely depends on the institutions where arrested and/or convicted persons are detained. Based on this hypothesis, the following factors characterising the work of, and conditions in, the institutions where arrested/convicted persons are held are focused on. These are the:

- general conditions in jails and prison system—space availability, the autonomy of a prison system from police, state prosecution and other government agencies and socioeconomic conditions

- framework conditions for radicalisation—indoctrination and the organisation of law-breaking groups, which involves the cohabitation of various types of criminals (leaders and ideologues of criminal or radical groups) and the free (undisturbed by law enforcement agencies) socialisation between them

- framework conditions for the continuation of law-breaking activities—the availability of communication channels with the outside world that may be used for the continuation of criminal or ideologically-based law-breaking activities and opportunities to avoid giving up criminal or radical activities despite being taken into custody.

This hypothesis posits that radicalisation will increase with the deterioration in general conditions in jails, and with improving framework conditions for radicalisation and continuation of law-breaking activities while in prison. To verify this hypothesis, this article takes three cases in which various types of radicalisation can be easily observed, yet the extent of radicalisation differs significantly. At the same time, all three cases share some common traits as far as the problem is concerned.

Temporally, the study is rooted in the past two decades. This time selection was made in order to preserve the relevance of the study so as to better inform the wider international public as to the dangers of dysfunctional penal systems. Also, this timeframe represents

- the accession of Romania to the EU and NATO and the issues it faces impacts its relationship to those organisations, such as its exclusion from the Schengen space,

- the continued transition of Russia away from its Soviet past and towards a still-indeterminate ideological place,

- the clear shift in Pakistan towards Islamic radicalism.

The study posits that the conditions prevailing in the jail system of respective country plays a crucial role in radicalisation and the article compares two general sets of parameters for the three selected states. First, the level and dynamic of deviant actors and behaviours – both of a general criminal nature and of a political/religious nature. This is done by comparing the known data on organised criminality, and other information on criminal activities, and violent activities by the radical political and religious groups (large-scale attacks and terrorism, etc.). Due to the nature of the problem, the situation is better characterized by qualitative description.

Second, the study compares the conditions prevailing in specific prison systems. This means both comparing known general data on capacities and needs, and other information on incarceration conditions in the three selected cases. Again, emphasis shall be made on qualitative description.

The aim of the study is to determine whether the correlation between these two sets of parameters – deviance prevalence and the situation in prisons – may be established. Additionally, similarities and differences in prison conditions in the three countries will be identified to make an attempt at explaining the specific problems with radicalization these countries face.

A Note on Case Selection

Prior to shifting attention to the case-work this article relies so heavily on, it is important to justify the deployment of three very different states in order to support the main hypothesis of this work.

First, these countries had and/or have to struggle with political, social and religious radicalism. While today’s Romania has few radical political groups, in the past it had a large and extremely sophisticated Orthodox radical movement called the Iron Guard. While this work limits itself to the contemporary period, it is important to note that Romania has a heritage of radicalisation. Russia – for its part – struggles with an assortment of radical political and religious groups—primarily (but not exclusively) Islamists. Pakistan has been waging a nascent war of attrition against a host of radical political and religious groups (re: Lashkar-e-Jhangvi) and large-scale radical insurgents such as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). In short, all the testing cases have a heritage of combatting radicalisation.

Second, – and in addition to radicalised groups – Romania, Russia and Pakistan all have mature criminal communities; although the degree of sophistication, areas of specialisation and specific traits differ. Briefly, Romania’s and Russia’s organised criminal communities are sophisticated and well-established with known projection on a global scale, helped on by very large and influential diaspora communities in important cities and states around the world. For Pakistan, the organized criminal community is mostly niche-centred in narcotics trafficking (heroin) on an industrial scale.

Third, while the investigation here commenced with Romania (as a starting point), it was important to select two additional cases to provide stronger evidence in terms of penal systems working against their intended goals to the point that they can be termed as – in some cases – incubators of radicalism of a political and/or criminal nature. So, while Romania and Russia share certain socioeconomic, religious, historical, political and cultural traits, they remain different enough as to be able to provide a more in-depth analysis of how radicalism is being produced by their penal systems’. This dyad is especially important since Romania joined the EU and NATO and the expectation that it reformed its judicial system should have set it apart from Russia, which went through a different set of post-Cold War changes.

Pakistan – in obvious contrast – is a completely different case from both Romania and Russia—an Islamic republic located along the frontiers of the Middle East (re: Iran) and the South Asian Subcontinent (re: India). Pakistan remains an under-modernised state (compared to Romania and Russia), was located in the US-led camp during the Cold War (it was not part of the socialist bloc), and is plagued by continuous political instability. Despite these differences however, the fact remains that all three cases have – on initial investigation – shown that some form of political and judicial dysfunction is producing radicalism among inmates rather than detention being a source of social rehabilitation.

This work now turns to a case-by-case evaluation of Romania, Russia and Pakistan in order to better understand what their particular penal situations are.

Romania: General Conditions in Jails and the Prison System

The main penitentiary institution in Romania is the National Administration of Penitentiaries which is situated under the supervision of the Ministry of Justice. At present, Romania has some 45 prisons and detention centres, of which 16 are referred to as maximum security prisons. Highlighting the most important stages in the formation of the modern Romanian prison system, we need to highlight the factors that played a crucial role in its formulation. In our view, the key event in the transformation of penal system in Romania was its transition from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and its placement under the Ministry of Justice as of 15 January 1991. This step was consistent with the standards prevailing in democratic countries of Western Europe. Transferring the control of prisons from the Interior Ministry to the Ministry of Justice was an indication that the prisons had become a social institution to solve practical problems, rather than punitive institutions meant to deter and punish.

An important process in development of the Romanian criminal justice system commenced on 01 February 2014 with the introduction of the new Romanian Code of Criminal Procedure which was considered ‘more than the Penal Code, the Code of Criminal Procedure is the test paper of democracy.’3 The new Romanian Code was adopted to correspond to the standards imposed by the European Convention on Human Rights. The expectation that Romania’s justice system was joining the ranks of the EU was, however, premature.

According to the statistics, the number of convicted persons increased dramatically after the collapse of communism in Romania. Three key explanations have been floated around Romanian institutions and media and offered to the EU to explain the rising prison population between 1991 and 2016:

- the rise in criminal behaviours that accompanied the transition to a market economy,

- the increasing of the length of confinement for maximum sentences,

- the absence of non-custodial alternatives.4

In other words, the working logic is that in the period of transition – of shifting from a centrally planned to a market economy – generated more criminal activities and more criminals. Romania’s judicial reaction to that increase was a platform of deterrence that increased mandatory minimal sentences for particular crimes. This swelled prison population came at a time when tremendous state budget cuts were taking place and the penal system was unable to cope. To make matter worse, Romania incarcerates nearly all convicted criminals and few non-custodial alternatives are visible. This implies that the already overstretched prison system becomes even more retarded since all levels of crime – from petty theft to murder – are punished by some form of incarceration and detention. In numbers, the prison population in 1989 was situated at some 29000. By 2001 that number had jumped to 50000. This growth negatively impacted prison conditions, which are often criticised for lacking adequate hygienic equipment, medical facilities and modern penal programmes for social rehabilitation.

Since the 2001 cresting of prison number, a sustained push by Romanian authorities to reduce prison-time coupled with the settling into the market system by Romania’s next generation have driven down prison number. As of this year (2016), only 28062 prisoners are recorded in Romania.5 However, reduced numbers and less-overcrowding has not stopped the radicalisation of incarcerated persons and the trend towards the opposite has not escaped EU attention—Romania’s prisons continue to be heavily criticised by European authorities and human rights activists.

Opportunities for Criminal Radicalisation in Romania

Most penal institutions in Romania remain overcrowded and although the total number of people locked into Romanian prisons declined over the past years, prison conditions remain poor and far below European norms. Overcrowded prisons, and improper detention conditions, brought 29 decisions against Romania in the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and the country is under threat of a pilot decision due to repeated violations of the European Charter of Human Rights. According to reports of the Association for the Defence of Human Rights in Romania, the Helsinki Committee and the Association for Human Rights and People Deprived of Freedom, most prisons in Romania were overcrowded and had inadequate conditions, including insufficient medical care, poor food quality, mould in kitchens and cells, understaffing, an insufficient number of bathrooms, poor hygiene, insects, an insufficient number of doctors (including no psychologists and psychiatrists in some prisons), lack of work and inadequate educational activities.6 The Council of Europe anti-torture committee (CPT) delegation visited Romanian prisons in 2014 and collected information of beatings to inmates by special intervention forces. The Romanian Minister of Justice very recently admitted lying to the ECHR about securing funds for new prison investments.

Overcrowding, as well as related problems such as lack of privacy, can also increase rates of violence and radicalisation. One of the most evident examples of this situation is the growing number of prison riots and at least 6 prison riots erupted so far in 2016 over poor conditions of detention.7 Prison riots illustrate how bad conditions of living may result in the outbreak of violence.

The Continuation of Law-Breaking Activities

In Romania, the percentage of former repeat offenders hovers around 54%—a fact that demonstrates – to a certain extent – the failure of penal politics in the country.8 There are many factors that push former inmates to return to criminality, though one stands out as being systemic and avoidable: post-incarceration opportunities.

Sociological research has indicated that in addition to the now routine fear of remaining unemployed and discriminated against after incarceration together with very high levels of drug abuse within prisons has led to a curious radicalisation among Romanian prisoners. This is reflected in specific gang recruitment within prison walls. While the Băhăian Gang is a case in point – having grown in strength and numbers since the leaders’ 2010 arrest and 2013 imprisonment – it is the wide collection of Romania’s Romani Clans that reveal the dangers of radicalisation. Of these, the most notorious are the Duduieni, Caran and Gigi Corsicanu Clan and the Feraru Clan, both of which have their leaders in prison. In both cases, membership of the organisations flowered since clan leaders entered the prison system; they exploit poor and vulnerable inmates for cooperation in and beyond Romania’s prisons. This is more than a local or even a national problem since many of the activities involve human, weapons and drug smuggling throughout Europe.

There is another side to the story of Romania’s justice system however and there are serious allegations that Romania continues to use its penal system for political reasons—to imprison government critics and intimidate others. This is dangerous because it has the potential of turning law-abiding citizens into national criminals for issues that are not regarded as criminal by other members of the EU and has strained relations with other EU members through the systemic misuse of the European Arrest Warrant (EAW) in pursuit of political dissenters. In this way, Romania lacks a true and neutral arbiter situated above the political classes.

Russia: General Conditions in Jails and the Prison System

According to the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service (FPS), some 645350 people were serving prison sentences in 2016.9 Russia’s main institution for law enforcement, control, and oversight of functions involving the punishment of persons who have been convicted of crimes is the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service. It was created in 2006 and was placed under the Russian Ministry of Justice. In 1990, the crisis of the criminal-executive system was due to lack of finances, but by 2000 the financial problems were solved. Currently, the FPS has the highest budget in Europe and it increased by almost 6 times from 48 billion roubles in 2004 to 269 billion roubles in 2015.10

But budget size cannot be an indicator of a high-level high-quality prison service. According to a report by the Council of Europe on the study of prison systems among member states, Russia, with the largest budget for Penitentiary Service among European countries, still spends 50 times less per capita than in the EU norm.

Between 1993 and 2001 a number of new laws were adopted in Russia that may be considered as major steps in aligning Russia’s prison system with prevailing international standards. The transition of the Penitentiary service from ministry of Interior to ministry of Justice took place in 1998. However, in 1990, the spiking problem of crime led to a hugely increased prison population—resulting in overcrowding and deteriorating conditions. In recent decades, the Russian incarcerated population was still tremendous, despite falling crime rates. The number of crimes in Russia has decreased by 38% for nearly 10 years. At the same time, the number of prisoners decreased by only 18%.11

Opportunities for Criminal Radicalisation in Russia

In the case of Russia, the radicalisation process in prisons may have both social and religious roots. Religious radicalisation is usually connected with jihadism and similar ideologies of religious-political violence. Muslim minorities make up approximately 12-14% of Russia’s population that can be compared with Muslim society in some European countries. But the overwhelming majority or Russian Muslims are not migrants. They are not isolated from the dominant culture and don’t perceive themselves to be rejected by society. But some of them, mainly youth, may be influenced by radical ideas from abroad. The religious radicalisation in Russian prisons was widely discussed in the media over the past 3-5 years because of ISIS propaganda and the swelling number of Russian Muslims fighting in the Syrian civil war on the side of the jihadists. Some experts are alarmed that some imprisoned radicals use the isolated prisons to recruit and integrate new members for terrorism.12

Religious communities in prisons offer a way out of isolation as well as new social networks, and may afford important physical protection against other prisoners. There are about 61 mosques and more than 230 prayer rooms in the Russian prison system. The number of official Muslim communities is more than 950.13 Prison authorities are fearful of the growing influence of illegal ‘prison jamaats,’ where young incarcerated Muslims may adopt extremist ideas. In 2016 the number of those convicted for terrorism and complicity in terrorism grew by 2.5 times. Despite that this category was among the smallest number, cases of terrorism is growing rapidly.14

The other kind of radicalisation you may find in Russian prisons is social radicalisation that is mainly connected with criminality. Russia’s prison system has its own peculiarities. The overwhelming majority of Russian penal institutions are situated separately and far from the cities, and have their own infrastructure. Historically, in Russia there were prison-towns and prison-villages, which are on its balance sheet settlements, highways, kindergartens, schools, stadiums and houses of culture. Due to its infrastructure, which involved prisoners and ex-prisoners in the economic life, is already a basis for their specific criminal environment.

The Continuation of Law-Breaking Activities

Over the last 10 years, statistics show a growing number of repeat offenders in Russia. Despite efforts by the state, the level of recidivism among previously convicted persons continues to grow. By 2013-2014, the proportion of previously convicted persons reached 44%-45%—an absolute record in the history of modern Russia.

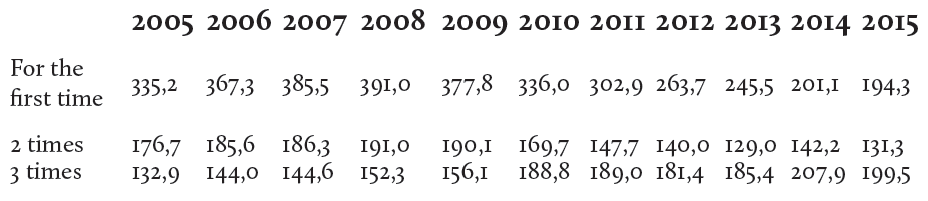

Criminal Recidivism in Russia, 2005-2015

The growing number of inmates that repeat criminal acts indicates the deep crisis of the penal system in Russia. People return time and again to prison, and use the experience to become members of criminal families. Prison in Russia does not heal, but prepares criminals for their next crimes.

Pakistan: General Conditions in Jails and the Prison System

Pakistan has, over the past two decades, faced huge organised criminal structures and politically (MQM) and religiously-motivated (TTP, Lashkar-e Jhangvi etc.) violent movements which resorts to armed struggle and terrorism. To a large extent, both criminal and ideational- driven law-breaking activities are interlinked, although this issue, as Hassan Abbas pointed out in the case of Taliban movement, remains ignored in many publications on the issue and points that also ‘criminal influences rally the group.’

Pakistani jails are overcrowded. For instance, in the late 2000s, Rawalpindi’s Adiala Jail accommodated 6195 prisoners although it had the capacity only for 1900.15 The situation seems to be consistent: in 2015 the same jail continued to struggle with over-crowdedness and more than 6000 people remained incarcerated there.16 The problems with general conditions of imprisonment in Pakistan cannot be reduced to over-crowdedness alone. While a high-security prison in Dera Ismail Khan has a lot of free places, the conditions are characterised by local observers as a ‘sweltering hell.’17

Every province of Pakistan regulates issues related to its prisons itself and even more difficulties exist because of the ‘lack of communication’ between prison administrations and Pakistan’s numerous security agencies.18 The methods of jails administration are unsophisticated. Prisoners are tortured and mistreated, yet there is no effective control of prisoners’ activities: ‘during that time in hell in Mach [jail] his beard turned pure white,’ complain the insurgents who go on to say that ‘jails, torture and suffering won’t change our jihadist commitment.’19

Due to such inhuman treatment and problems in the justice system the prison system has a serious image problem. To get incarcerated in many cases probably means that arrest (and even more – conviction of a person) in pubic opinion does not necessarily means labeling the person as socially destructive or vicious. On the contrary, there are signs that the contrary can happen—such a person receives positive support as a victim, or even hero, who challenged a corrupt and unjust system. According to one Taliban fighter, ‘long imprisonment hasn’t slowed down our momentum, resistance and commitment to the fight.’20

Labelling starts early with very easy resorting to taking into custody. Even Pakistani officials complain of the ‘routine use of pre-trial detention, even for non-violent offences.’ Many people waiting for their trial or are in under trial and not convicted, spend years in prisons. Actually the number of those awaiting trial far exceeded (in the 1990s) the number of convicted criminals in the country’s jails and there are no signs of improvement in this regard afterward.21

Opportunities for Criminal Radicalisation in Pakistan

Religious and political radicals are held together with ordinary criminals and members of organised criminal structures.22 Since the late 1990s, there were reports that the convicts are held together with prisoners awaiting the completion of their trials and in many cases it was reported that adults were held in the same cells as minors.23 Then, in the late 2000s, for instance, in Adiala Jail in Ravalpindi only 1972 prisoners served their terms while 4223 were in the prison while awaiting trial.24

Control over prisoners is very low due to insufficient resources and competency of prison personnel. The level of the control methods is illustrated by the fact that most prisons lack psychologists and other advances medical treatment. According to the former head of Punjab police, ‘our government focuses more on providing vocational training to criminals than on psychological therapy.’ And, it was only in April 2015 that the prison administration in the biggest Pakistani province of Punjab decided to train prison personnel in criminal psychology. Moreover, it was announced that ‘hardened criminals [...] currently detained […] for terrorist activities, sectarian killings and other crimes of a heinous nature who will be given specialised psychological therapy.’25

The reality of gang activities inside Pakistan’s prisons have existed on an industrial scale for many years. Although the report of 150-strong tribally-based gang (biradri) in a jail in Sindh province, which pursued various activities ‘ranging from openly selling narcotics to criminally assaulting small children in the adjacent children’s jail’ refers to during the late 1990: the problem has remained.26

The Continuation of Law-Breaking Activities

A paradoxical situation is clear: on one hand, some observers complain that in Pakistan ‘Taliban prisoners simply disappear into a black hole with no possibility of contacting their families and no protections under the Pakistani constitution.’27 On the other hand, prisoners frequently continue to keep outside contacts involving continuation of their law-breaking activities. Thus, even in ‘a heavily guarded jail considered one of the most protected prisons in the province,’ prisoners apparently got what they needed brought inside and outside by ‘sympathetic wardens,’ and managed to communicate with the Taliban by cell phones.28 The problem of illegal communications is well known to prison authorities in Pakistan.29

Pakistani prisoners do not have much motivation to stop or even reduce law-breaking behaviours not only because they can stay in touch with their criminal or radical comrades but also because they can hope to soon get their physical freedom. There are wide opportunities for them to be released than in other countries. First, Pakistani government practices massive releases of prisoners as a ‘good will gesture’ meant to achieve some political aims. However, some observers believe that ‘the prisoner releases seem to have only succeeded in funneling commanders and fighters back to the fighting.’30

Second, jailbreaks are a regular occurrence and organised collective escapes, some of them involving hundreds of prisoners – e.g. in April 2012 and July 2013 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province – are not especially rare. In this former case, prison guards did not resist the break-out and reportedly not one of those involved in freeing the prisoners was killed: ‘the militants asked them to get aside and leave.’31

Such porous barriers between prisons and outside world of law-breaking communities cannot but foster radicalisation of both criminal and extremist political-religious communities. A spectacular case of such radicalisation involves a religious extremist who, after a stint in Guantanamo Bay prison, was re-arrested in Pakistan. Despite spending five years in a jail run by the Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) agency he not only re-joined the extremist community, but quickly rose to become the Taliban overall commander for southern Afghanistan.32 This demonstrates that imprisonment failed to isolate him, and, on the contrary, provided him – like many others prisoners – with a “heroic” image.

Pakistani prisons create excellent conditions for the continuation of law-breaking at ever higher levels of intensity and sophistication. The combination of criminal radical elements in Pakistan has produced consequences for the prison system as well. According to Khalid Abbas, (then) inspector-general of Pakistan’s prisons, ‘either the government should voluntarily hand over jails to [the Taliban] or it should take serious measures and build a high-security prison [for terrorists and sectarian militants]. The existing jails have been built to keep ordinary prisoners.’33

Conclusions

The research conducted in this study generally confirmed the main hypothesis and it is clear that the intensity of problem of radicalization – both of a general criminal and ideational (political or religious) nature – correlated with the deterioration in general conditions in jails, and with improving framework conditions for radicalisation and continuation of law-breaking activities while in prison. At the same time, there are clear differences between the countries under investigation— which can be explained by differences in the intensity of the third factors which we studied as those constituting the conditions for radicalisation in prisons. Concerning the problem of radicalisation, Romania fared better than Russia and Pakistan owing to better general conditions in Romanian prisons. However, Romanian prisons remain a hotbed for criminality and criminal radicalisation. The situation in Russian and Pakistan looks similar to each other though, with Russia, generalisations were deployed since the country is huge and conditions in jails differ immensely region to region.

How can these finding be interpreted?

Poor conditions in jail encourage prisoners to continue their illegal activities and socialise with other, likeminded, people. Jails can fail to become real hurdles for criminal and extremist activities, especially when corruption (in Romanian, Russia and Pakistan) and porous security (largely Pakistan) make them penetrable. If somebody is interned in such an ineffective prison does not necessarily put an end to his or her law-breaking activities since s/he may be freed (massive escapes at Pakistani jails, politically-motivated releases and amnesties), removing one more reason for some to give up their deviant behaviour.34

Likewise, the perception of prisons by wider populations matter. Prisons are not only for criminals but also for those challenging an unjust system or those who by accident and without any guilt become the victim of the unjust system. In reviewing the casework for this article, several high-profile examples have surfaced as to people incarcerated for political reasons. This is similar in all three of the cases under scrutiny— Romania, Russia and Pakistan.

Prison conditions, the harshness, inhumane, abusive and humiliating practices of prison personnel together with other deprivations do not positively rehabilitate criminals regardless whether they follow general criminal behaviours or political and religious ideologies. Instead, they conceal the lack of efficient strategies, tools and resources for de-indoctrination and bringing them to more socially acceptable behaviour. The exception to this is, of course, those that are imprisoned for political reasons; an area that requires further research and investigation.

Notes

1 Edwin M. Lemert (1951), Social Pathology: A Systematic Approach to the Theory of Sociopathic Behaviour, McGraw-Hill.

2 Ibid, p. 82.

3 F. Ciopec and M. Roibu (2016), ‘The New Romanian Code of Criminal Procedure: Cosmetics or Surgery?’ International Report, at: <http://www.lalegislazionepenale.eu/>.

4 Mitchel P. Roth (2006), Prisons and Prison Systems: A Global Encyclopaedia, Greenwood Press, Westport, USA. p. 228.

5 ‘Romania, World Prison Brief.’ The International Centre for Prison Studies, at: <http://www.prisonstudies.org/country/romania>.

6 ‘Romania 2015 Human Rights Report,’ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2015 United States Department of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labour.

7 ‘Inmates Continue Protests in 13 Romanian Prisons,’ Romania-Insider, 15 July 2016 at: <www.romania-insider.com/inmates-continue-protests-13-romanian-prisons/>.

8 Gabriel Tical and Maria Roth (2012), ‘Are Former Male Inmates Excluded from Social Life?’ European Journal of Probation, 4:2, pp. 62-76.

9 ‘The Federal Penitentiary Service of Russia,’ (2016) at: <http://fsin.su/ structure/inspector/iao/statistika/Kratkaya%20har-ka%20UIS/>.

10 Ольга Киюцина (2016), ‘Кому тюрьма, а кому дом родной,’ Газета.Ру, at: <www.gazeta.ru/comments/2016/05/31_a_8275145.shtml>.

11 ‘Практика рассмотрения ходатайств о досрочном освобождении осу- жденных в российских судах,’ Аналитический отчет (версия для контро- лирующих органов); под ред. О.М. Киюциной, ИПСО. – СПб., 2016. С.10.

12 Григорий Туманов (2016), ‘Зеленая зона,’ Коммерсант, at: http://kommersant.ru/doc/2901612

13 Силовики начинают ломать тюремные джамааты России. // ИАП ON KAVKAZ. http://onkavkaz.com/news/690-siloviki-nachinayut-lomat-tyuremnye-dzhamaaty-rossii.html 02.01.2016

14 Михайлова Анастасия, В России в 2,5 раза выросло число осужденных за терроризм. http://www.rbc.ru/politics/17/08/2016/57b32ed49a7947d75149ff95#xtor=AL-[internal_traffic]--[rss.rbc.ru]-[top_stories]

15 Hassan Abbas (2014), The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier, Yale UP, p. 3.

16 Mohammad Asghar (2007), ‘Adiala Jail: Prison Life is a Living Hell, at: <http://www.dawn.com/news/260357/adiala-jail-prison-life-aliving-hell>.

17 ‘Haseeb Bhatti Among Murderers: A look Inside Adiala Jail,’ 2015, at: <http://www.dawn.com/news/1196693>.

18 Abubakar Siddique (2013), ‘Pakistani Prison: A “Sweltering Hell” Militants Launch Pakistani Prison Attack, RFI/RL, at: http://www.rferl.org/content/pakistan-prison-sweltering-hell/25061513.html

19 Saud Mehsud (2013), ‘Mass Jail Break in Pakistan as Taliban Gunmen Storm Prison, Reuters, at: <http://www.reuters.com/article/us-pakistan-prison-attack-idUSBRE96S0WG20130730>.

20 Ron Moreau and Sami Yousafzai (2013), ‘Freed Taliban Prisoners in Pakistan and Afghanistan Return to Jihad,’ TDB, at: <www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2013/12/06/freed-taliban-prisoners-in-pakistan-and-afghanistan-return-to-jihad.html>.

21 Ibid.

22 Asghar (2007).

23 Siddique (2013).

24 ‘Prison Bound: The Denial of Juvenile Justice in Pakistan,’ Human Rights Watch, 1999, at: <www.hrw.org/reports/1999/pakistan2/Pakistan-03.htm>.

25 Asghar (2007).

26 Ihsan Qadir (2015), ‘Pakistan Fights Terrorism with Therapy for Violent Prisoners,’ UPI, at: <www.upi.com/Pakistan-fights-terrorism-with-therapy-for-violent-prisoners/71423538815150/>.

27 Q. A. Bukhari (1998), ‘Jhang: Drug Trade, Biradrism Destroy Jhang Jail Peace,’ Dawn.

28 Moreau and Yousafzai (2006).

29 Mehsud (2013).

30 Asghar (2007).

31 Moreau and Yousafzai (2013).

32 Ismail Khan and Declan Walsh (2012), ‘Taliban Free 384 Inmates in Pakistan,’ New York Times, at: <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/16/world/asia/pakistani-taliban-assault-prison-freeing-almost-400.html?_r=0>.

33 Moreau and Yousafzai (2013).

34 ‘Militants Free 250 Inmates In Attack On Pakistani Prison,’ RFE/RL, 30 July 2013, at: <http://www.rferl.org/content/pakistan-prison-attack/25060666.html>.

About the Authors

Siarhei Bohdan is currently working on his PhD thesis at the Freie Universität Berlin. Until October 2009, Siarhei lectured at the European Humanities University in Vilnius and worked at the Nasha Niva weekly.

Gumer Isaev is the Director of the Center for Modern Middle Eastern Studies.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.