Russian Analytical Digest No 215: Russia before the Presidential Elections 2018

14 Mar 2018

By Evgenia Olimpieva, Andrei Semenov, Sergei Gogin and Inga Saikkonen for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The four articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 9 March 2018.

Who Is Ms. Sobchak?

By Evgenia Olimpieva

Abstract:

Ksenia Sobchak is unfairly dismissed as a pro-Kremlin candidate with the potential to hurt the opposition. Her decision to run should be understood in the context of post-election politics. Instead of being condemned, she should be welcomed and supported as a strong addition to Russia’s opposition ranks.

Controversies around Sobchak

In October 2017, Ksenia Sobchak—the daughter of St. Petersburg’s first democratically elected mayor, a former reality TV show host, a political journalist, and an opposition activist—announced her decision to run in Russia’s presidential elections scheduled to take place in March 2018. Sobchak’s decision to run has stirred considerable controversy and has been largely condemned by the Western and Russian media. A recent article published in The Economist is indicative of this trend. While being generally respectful of Sobchak and admitting that she “might be a genuine liberal,” it argues that her participation in the elections only serves to spoil anti-corruption crusader Alexei Navalny’s agenda and split the opposition into competing camps while also benefiting the Kremlin in its goal of legitimizing the elections and increasing turnout. The Economist is neither the first nor the only publication to make such claims about Sobchak. Moreover, in an interesting twist of events, liberal Western and Russian independent and state-controlled media are similar in how they portray Sobchak as a spoiled child of the nineties, unfit for politics and only capable of participating in it as an entertainer, serving as “a clown,” “a parody,” and “a circus actor.”

Perhaps, such an attitude is not surprising considering Sobchak’s personal and professional history. The daughter of Anatoly Sobchak, a major liberal political figure of the 1990s, Sobchak gained fame as the host of a popular reality television show “Dom-2”1. While Sobchak’s recognition rating today is around 95%, she is mostly associated with her work as an entertainer. Her connection to “Dom-2” remains, even though she had a successful career as a journalist working at the opposition television channel Dozhd where she had her own show.

The other controversy around Sobchak’s candidacy is her alleged closeness to President Vladimir Putin personally. In the 1990s, when Ksenia Sobchak was very young, Putin worked for her father and, according to Sobchak, did a lot to help her father later on. During her first press conference as a presidential candidate, she said that she was not going to attack Putin personally even though she intended to criticize him as a politician. This attitude gradually developed into a campaign that calls for Putin’s peaceful departure from politics along with his allies with no lustration to follow. By contrast, Nalavly’s campaign essentially seeks to throw Putin and his cronies into jail. While there is no evidence that the ties between Putin and Sobchak’s family in the nineties translated into some special relationship today, the close acquaintance linking Sobchak and Putin has led many in Russia and abroad to quickly dismiss Sobchak as a pro-Kremlin candidate.

The circumstances under which Sobchak announced her candidacy only made the situation worse. Her announcement followed an article published by Vedomosti newspaper quoting a source close to the Kremlin who leaked the information that the Kremlin was looking for a woman to run against Putin and that Sobchak was on the list of possible candidates. What added fuel to the fire is the fact that after the announcement of her candidacy, Sobchak was invited to participate on a number of shows aired on governmental channels, something that would be unthinkable for a candidate like Navalny, whose name state officials are forbidden to pronounce in public. “Why would she be allowed on TV after years of being banned due to her opposition activity?” wondered journalists and observers and bombarded Sobchak with the same question. She must be in bed with the Kremlin, they surmised.

A Strange Portrait

The supposed closeness to Putin and Russia’s political elites in combination with her fame as a media persona has led to Sobchak being portrayed not only as a “clown”, but as the Kremlin’s clown. Agent-Clown-Sobchak is sent out into the world to fulfill a complex and multifaceted Kremlin plan to, on one hand, spoil the party for the opposition by providing an illusion of representation for the urban elites, undermining Navalny’s calls to boycott the elections, and thereby creating divisions among those opposed to Putin, and on the other, to make gains for the Kremlin by increasing turnout and support for the president while legitimizing the elections with her presence. What follows is that Sobchak, on top of being an agent and a clown, must also be a superwoman, for while being a joke, she is apparently capable of providing impressive political results.

The combination of conspiracy thinking and plain sexism, two powerful forces, are the only way to make sense of Sobchak’s strange media portrait in Russia and the West. While the claim that the Kremlin controls everything is not something new—even Navalny at some point was accused of being the Kremlin’s agent— the sexism part, perhaps, requires additional explanation. Had Sobchak not been a woman with a history of being involved in a typically “feminine” type of show business (a reality show about relationship-building), reactions to her decision to run would not have been so unanimously negative. Young, rich, glamourous, and blonde, not afraid to swear and make fun of herself, Sobchak just makes for an easy target.

Legitimate Concerns

Of course, in some sense it is justified to be concerned about Sobchak’s participation in the 2018 presidential elections, especially given the logic of regime change mechanisms. Elections matter even in an electoral authoritarian country like Russia, just for different reasons than they do in democracies. As scholars of authoritarian regimes show, autocrats must ensure a credible and decisive victory. Winning by a large margin provides “an image of invincibility” to those in power, which sends an important signal dissuading potential challengers.2 Such an image is especially crucial for Putin, who is getting older and for whom this could be the last term. Anticipation of his departure could lead to the dissolution of his coercive powers, as the elites begin thinking about a future without him in power.3 Thus, it is possible that the weaker he appears in these elections, the greater could be the chances of a democratic transition.

One can debate whether Sobchak’s decision to participate as a candidate “against all4” or Navalny’s election boycott will do more to weaken Putin’s result. But chances are that neither of these strategies will have a major impact and Putin, most likely, will be re-elected by a large margin regardless.

Looking Beyond 2018

In this context, trying to understand Sobchak’s role in the presidential elections of 2018 is not particularly interesting. It is more productive to shift focus from Sobchak as a presidential candidate in 2018 to Sobchak as a newborn player and an opposition politician in Russia’s political arena. Once these elections are over, they will be followed by six more years of Putin’s rule, parliamentary elections in 2021, and, crucially, the presidential elections of 2024. The latter are especially likely to be full of uncertainty, since there is a strong possibility that Putin will not participate. It is from the perspective of what is to follow the presidential elections of 2018 that Sobchak’s decision to enter politics should be viewed and, as I will argue here, welcomed.

Sobchak should be received first and foremost as a strong addition to the camp of opposition leaders in Russia. She differs from billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov, who disappointed all who voted for him in the 2012 presidential elections by essentially disappearing in their aftermath. Sobchak appears determined to stay in politics, to build a party and to run for the Duma. Taking into account the dearth of contenders in the opposition camp, Sobchak’s decision to enter politics should only be welcomed. While Navalny is an impressive politician, not everyone in Russia is ready to support him. The old-timer and Yabloko party leader Grigory Yavlinsky is getting on in years and is increasingly out of touch.5 Boris Nemtsov, the only well-known, young, charismatic opposition leader with political ties to the pre-Putin era, was murdered in 2016, leaving a gaping hole in the opposition ranks.

Of course, there is always a concern that a new player in the political arena will cause new divisions. Some are worried, for instance, that Sobchak could drive a wedge between Navalny’s supporters. It is hard to see, however, why Navalny’s supporters would quit being Navalny’s supporters simply because Sobchak is now out there. Instead, it is likely that the overlap between Navalny’s and Sobchak’s supporters will be small and that she will mobilize a different group of people.6 She could attract the support of women (especially young women), entrepreneurs, university students and young professionals whom her campaign clearly targets. Finally, she could be supported by those who backed her father in the past and who remember the nineties as a time of democratic promise rather than an economic disaster (those people do exist). If those people are out there, unhappy with the regime, but unconvinced by Navalny for one reason or another, Sobchak is well positioned to bring them out of the limbo of political passivity.

Moreover, Sobchak is not an addition that should be taken lightly. If her campaign is indicative of anything, she will be a fearless and uncomfortable opponent of the Kremlin. One example is her appearances on state TV. Regardless of what one thinks of Sobchak as a politician, it is hard not to be impressed with her performance on the Evening with Solovyev, 60 Minutes, or Time will Tell—the notoriously nasty political shows aired on Russia’s main state-controlled channel Rossiya 1. Descended into the tank with the Kremlin’s chief propaganda sharks, Sobchak came out on top by addressing almost all of the most sensitive topics in Russian politics, usually either forbidden on state television or presented in a way that distorts reality. She answered difficult questions, navigated the provocations and manipulations, simply talked over the show hosts when they sought to intimidate her, and bombarded them with facts: Putin is afraid of debates, Crimea is Ukrainian, and Navalny is illegally prevented from running. Being a media insider surely helped Sobchak stand her ground and fight as an equal opponent in a situation with a highly skewed playing field. She made Vladimir Solovyev7 come close to losing his temper and Artyom Sheinin8 turn to the weapon of last resort and wear a red clown nose. The point was surely to delegitimize Sobchak and her words and to turn the debate into a circus and Sobchak, once again, into a clown.

It is hard to say what takes more guts: not losing your temper in the face of a “journalist” with a clown nose on, or traveling to Chechnya for a single-person protest against the arrest of a human rights activist, as Sobchak did on January 28, 2018. Sobchak’s confrontation with Kadyrov and her statement that a woman can easily be the next leader of the Chechen Republic could be the topic for a separate paper. Her role as a female candidate, which she has only gradually been embracing, could be the topic for yet another one. Here it will suffice to say that a person like Sobchak should be welcomed in the opposition ranks at the very least for her ideological convictions, determination, fearlessness and strength. Sobchak in politics, Sobchak in the opposition, and potentially Sobchak in the Duma (and who knows, Sobchak as a presidential candidate in 2024?) are all potential positive outcomes of her decision to run in the presidential elections this year and the more support she gets, the more likely these outcomes are to materialize.

Notes

1 Dom-2 was an extremely popular reality TV show in the early 2000s. In the show, the couples worked at the construction site of a house that will become a future home for one of them if they succeed in building their relationship as well.

2 For the importance of the “image of invincibility” achieved through elections, see Magaloni, Beatriz. Voting for autocracy: Hegemonic party survival and its demise in Mexico. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

3 Hale, Henry E. Patronal politics: Eurasian regime dynamics in comparative perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2014. “It often happens that elites come to expect a patronal president’s imminent departure from power, and this can undermine the president’s capacity to shape elite expectations…the value of presidential promises and gravity of her threats start to dissipate. The president can become a ‘lame-duck’” (p. 84).

4 Since the ballot line “against all” was cancelled in Russia in 2006, the original idea behind Sobchak’s decision to run was to serve as a candidate “against all” so that people could express their dissatisfactions with available candidates by voting for her. Even though Sobchak now has a program and larger political ambitions than being a candidate “against all”, this idea is still important for her presidential campaign (<https://lenta.ru/ news/2018/01/17/reiting/>)

5 Despite the brevity of her campaign, Sobchak’s ratings are very close, even slightly surpassing Yavlinsky’s as the latest polls conducted by the government-sponsored Russian Public Opinion Research Center reveal (<https://2018.wciom.ru/ index.php?id=1234>). Unfortunately, since the only independent pollster Levada Center was labeled a foreign agent, they cannot reveal the results of their polls until the elections are over and we are forced to rely on governmental data.

6 Unnamed sociologists (probably from the Levada Center since they are still conducting research without publishing it) argue that Navalny’s and Sobchak’s audiences only overlap by 20% as revealed by Echo Moskvy Editor-in-Chief Alexander Venediktov: <https://echo.msk.ru/ programs/personalno/2143196-echo/>.

7 The host of the Vecher s Solovyevym (Evening with Solovyev) television show on Rossiya 1.

8 One of the hosts of the Vremya Pokazhet (Time will Tell) television show on Rossiya 1.

About the Author

Evgenia Olimpieva is a second year PhD student in comparative politics at the University of Chicago. Her interests include authoritarian regimes and transitions, protest movements and the politics of memory.

Russian Systemic Opposition Candidates in the 2018 Elections

By Andrei Semenov

Abstract:

In Russia’s March 2018 presidential elections, the systemic opposition has little chance of replacing Putin. This article explores why these candidates run and examines their platforms in terms of politics, the economy, social policy, and foreign policy. Ultimately, these candidates do little to challenge the status quo.

A Weak Challenge to Putin

On 7 February 2018 the popular independent media outlet Meduza published an online quiz entitled “10 Strokes or 20 Steps? An Absurd Political Quiz about the Program Titles of the Presidential Candidates,” which parodied the striking similarity in the way that all the candidates but Putin (who had not yet revealed his program) framed their major programmatic documents. Vladimir Zhirinovsky, who is running for the sixth time, has a 100-point program entitled “Powerful Breakthrough Forward!” while first-timer Communist of Russia nominee Maksim Suraikin preferred “Stalin’s Ten Strokes”. Ksenia Sobchak’s “123 Difficult Steps” competes with “Pavel Grudinin’s 20 Steps,” and Yavlinsky’s “Road to the Future” in a way that mirrors Sergei Baburin’s “Russia’s Pathway to the Future.” It seems like the opposition candidates, regardless of their ideological positions or experience in politics, collectively assume that changing power in Russia is not going to be easy or straightforward. Indeed, both the Public Opinion Foundation (FOM) and the All-Russian Public Opinion Polls Center (VCIOM) surveys indicate that the average share of voters favoring Vladimir Putin ranges from 67 to 73 percent of those who intend to come to the polling station, while the other candidates trail far behind, at less than 10 percent.

With these numbers—and the absences of Putin’s primary opponent Aleksei Navalny, whose appeal to the Supreme Court regarding his right to participate failed in December 2017—the presidential race looks like a one-man show. This situation poses a simple question for the rest of the challengers: Why participate? Is there any strategic logic behind their bid for the presidency?

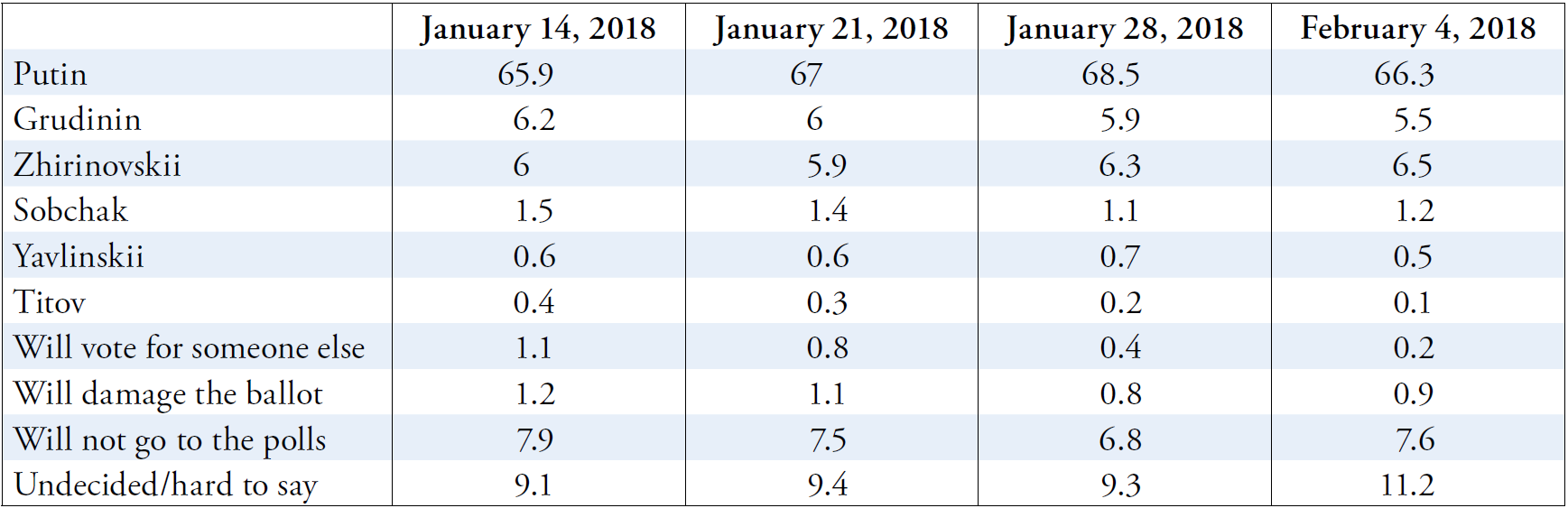

Apparently, some of them do not even claim to challenge the incumbent, like Party of Growth leader Boris Titov or Maskim Suraikin. Yet, the old systemic opposition (LDPR, KPRF, and Yabloko) have to make at least an attempt to look like they seriously think this race will get them as far as the second round. Strong appeals to their core constituencies, swing voters and those who remain undecided, carefully crafted slogans, and the means to communicate them to the target groups would be beneficial in this regard. If the opposition could manage to capture a sizable chunk of Putin’s electorate and persuade those in doubt (FOM polls report that the latter category amounts to about 10%, see Table 1.), this would indeed force a second round. Assessing the probability of this scenario is a worthwhile task since the stakes are high and the ramifications important. I will do that here, comparing the political platforms and some tactical choices made by the systemic opposition given the state of affairs in Russian public opinion. I will structure the assessment around the usual topics like politics, the economy, social policy, and foreign policy, a list that is more heuristic than precise as the candidates and public tend to mix them up.

Politics and Governance

Given their structural disadvantages, it comes as no surprise that systemic opposition parties promise constitutional reforms of some sort: Zhirinovsky calls for a unitary state with thirty provinces and the abolition of the Federal Council; Grudinin and Yavlinsky pledge to restore the four-year presidential term and increase parliamentary powers. All of them mention the need for an independent judiciary. Only the leader of Yabloko refers to civil and political rights and their protection in a meaningful way. Overall, politics occupies a relatively small space in the candidates’ agenda, and even if it appears, the claims are formulated in vague terms like demands for “free and fair elections” or “stronger self-governance.” Extravagant measures devoid of the content like Grudinin’s idea to create a “Supreme State Council” that will check presidential power or Zhirinovsky’s unicameral parliament showcase the unimportance of this topic. Although all candidates agree that the national legislature should gain more political weight (Grudinin talks about “greater accountability” for the president vis-à-vis the parliament, and Yavlisnky argues for a wider set of competencies), none of them advocates the immediate transition to a parliamentary republic—a point made by Aleksei Navalny as part of a comprehensive set of political reforms.

The disregard of politics definitely reflects the state of public opinion: only 4 percent of the population lists limits on civic and democratic rights among Russian society’s “salient problems,” according to a Levada-Center August 2017 opinion poll.1 Asked about necessary constitutional reforms or amendments, 10 percent of Russians think about their wellbeing and demand the right to have a minimum salary/pension enshrined in the Basic Law. A different 10 percent seeks additional guarantees for state-financed healthcare and education systems that provide services “free of charge.” Again, human rights protection is mentioned in a mere 3 percent of the answers. Aleksei Kudrin’s Center for Strategic Development 2017 study also reveals that for the next 10–15 years Russian citizens rank civil rights protection in 11th place, on par with the task of raising the country’s prestige—far below “increasing defensive capacity” and even further from anti-corruption measures2, which 33 percent of respondents regard as a fundamental problem. On the latter issue, there is a solid consensus among candidates that corruption constitutes a severe threat to the country’s future. However, none of them advocate any specifics.

Economy

The economy dominates both the public agenda and candidates’ programs. According to the same Levada poll mentioned above, rising prices worry 61 percent of the population, poverty 45 percent, unemployment another 33 percent, the economic crisis 28 percent, and inequality 25 percent. Consequently, the candidates line up to pledge dramatic changes in the state of the economy. The choice of tactics is designed to magnify the effects of their statements: on the liberal flank, Yavlinsky exploits his academic and professional background and lectures the public about the need for a windfall profit tax and a basic income, deregulation, legal and institutional protection of property rights, and redistribution of tax revenues between the center and the regions. Low workforce productivity, inefficient governance and weak institutions, insufficient funding for science and education, and insufficient links to global financial and technological flows are listed among numerous other obstacles for economic growth.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, the KPRF’s candidate, who happens to be the director of a successful privately owned agricultural company with substantial foreign financial assets, visits factories and argues for a new industrialization, increased support for national producers, and withdrawal from the World Trade Organization. Nationalization of the “strategically important and systemic industries” would follow Grudinin’s election alongside a progressive tax system and price and tariff control measures. Zhirinovsky’s program predictably consists of populist statements about industrialization, taxation on excess profits, and lowering the burdens for small and medium-sized business. Both the LDPR and KPRF candidates trace the current state of affairs in the economy to the 1990s market transition: in their view, inequality and social injustice stem from privatization and other “mistakes” made by Yeltsin’s government. Interestingly, Navalny’s program conflates these populist measures of the leftists with the liberal conduct of economic policy, making him indispensably appealing to both sides of the opposition electorate.

Social Policy

On par with the economy, social policy appears to be a point of reference for most Russian citizens. Pensions, social welfare, education, and healthcare are perceived as state obligations, and the vast majority of Russians demand access to these goods. The salience of pensions reflects troubles with the transition from the Soviet welfare system to the market economy. Savings and other forms of investments cannot make up for low payments: according to the 2016 Russian Eurobarometer, only 52 percent of the population had savings in the bank (Romir reported 57% in June 2017)3. Hence, the candidates try to balance the evident need to propose at least some reforms in this area with the reassurance of preserving the status quo. Although all of them criticize the current pension system, Grudinin unequivocally rejects the idea of raising the retirement age, Yavlinsky mildly supports it and advocates refilling the funds with dividends from state-owned companies and oil-and-gas export revenues. These steps are unlikely to compensate the Pension Fund’s deficits. In contrast to his competitors, Zhirinovsky remains optimistic and calls for raising pensions without any apparent financing to support his generous outlays. Likewise, candidates compete with each other in promises to increase social spending, primarily for science, education, and healthcare.

Obviously, in this vein, the opposition cannot outpace the incumbent: Putin’s last term (apart from foreign policy initiatives) has been increasingly tilted towards paternalistic social policy with the May 2012 decrees providing generous benefits to constituents. As a result, the public does not view the opposition as an alternative to the status quo—a point that applies to Navalny’s program too as he criticizes “systemic liberals’” for their attempts to raise the retirement age, though he proposes no remedy beyond a redistribution of public revenues to the “Future Generations Fund” and some “effective and just stimuli for a late retirement”. From this perspective, nobody on the opposition side can claim their share of Putin’s electorate.

Foreign Policy

In the foreign policy sphere, the contrast between liberal and nationalist opposition camps is more pronounced. Yabloko and Yavlinsky defend their well-known pacifist and internationalist position and demand the withdrawal of all military units from Eastern Ukraine and Syria, and the normalization of relations with the Western democracies. Yavlinsky even put it at the forefront of his program as “steps of prime importance” and calls for an international conference on Crimea. Grudinin and Zhirinovsky do not share this approach to international politics: both are outspoken supporters of Russian military operations abroad and demand recognition for the Luhansk and Donetsk separatist regions; both are anti-NATO and anti-Western; finally, both are likely to keep defense spending at its current level. The LDPR candidate rather mundanely expresses anti-migrant sentiments and promises to limit their number in Russia—a position which is close to Navalny and some of his constituencies.

The Road to What Future?

More generally, each systemic opposition candidate conveys a message to his fellow citizens about the great value of living in Russia. They all seem to gravitate naturally toward some “grand narratives” on Russian history and culture. The Russian world and the Orthodox Church are the linchpins of Zhirinovsky’s worldview, Grudinin represents the “national-patriotic” strand and praises Josef Stalin for his wise rule, and even Yavlinsky sometimes sounds like he is more concerned with writing a history book about Russian greatness than running a campaign. The March 2018 elections provoke reflections about the past as the participants from the systemic opposition are unlikely to implement their specific proposals in the nearest future. However, it is hard to say that their reflections are in any way visionary or challenging to the dominant narrative.

It appears that in both their policy proposals and prospective ideas the opposition candidates remain captives of their structural position and core constituencies: they hardly ever criticize Putin, prefer to feed their voters with conventional promises (save for some of Zhirinonvsky’s typical extravagances) rather than challenging them with novel directions, and their narratives of the future are not powerful enough to change the status quo. Against this backdrop, Navalny’s campaign indeed is a breakthrough from the status quo in the opposition camp. Grudinin might appear in Yuri’s Dud’s YouTube program, and Zhirinovsky might make a cameo on Tverskaya street in Moscow during an anti-corruption rally, however, it does not bring the systemic opposition closer to the most important job in the country. Perhaps, these candidates gain little traction because the word “systemic” still dominates the word “opposition”.

Notes

1 Samye ostrye problem [The Most Salient Problems]. Levada-Center opinion Poll. <https://www.levada.ru/2017/08/31/ samye-ostrye-problemy-2/>

2 Sociokulturnye factory razvitiya i uspeshnogo vnedreniya institutsionalnyh preobrazovanii [Socicultural Factors of Innovative Development] Center for Strategic Initiatives, <http://csr.ru/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/report-sf-2017-10-12.pdf>

3 Vahstein Viktor, Stepantsov Pavel Sberegateln’nye strategii naseleniya [Saving Strategies of the Population] Russian Academy of Public Service and Economy <https://www.ranepa. ru/images/News/2017-03/14-03-2017-opros.pdf>

About the Author

Andrei Semenov is the director of the Centre for Comparative History and Politics, Perm State University.

Table 1: “If You Vote in the Presidential Elections, Who Will You Vote For?” (in %)

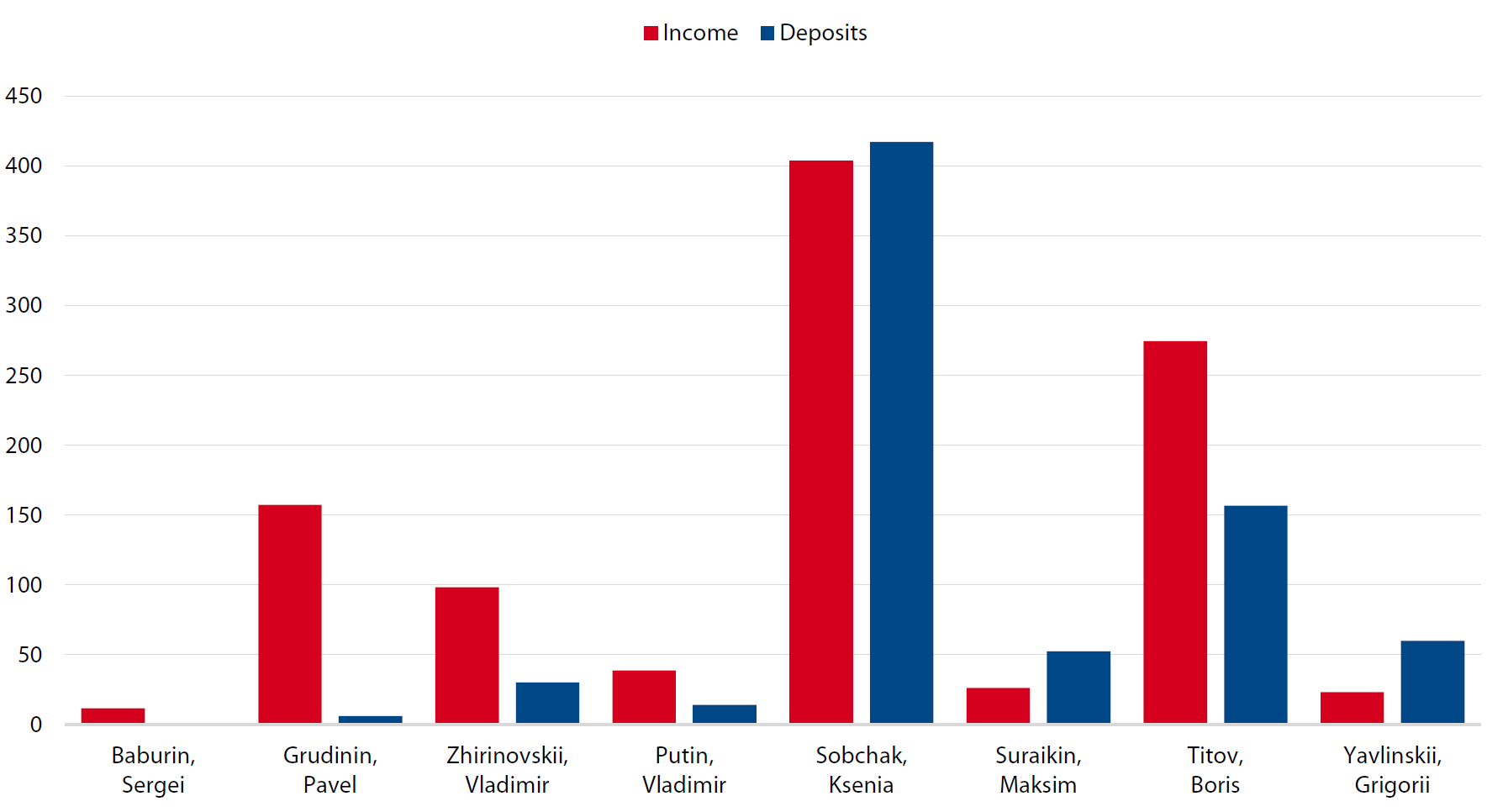

Figure 1: Candidates’ Six-Year Income and Current Bank Deposits (in mln. of rubles)

Generation Crimea

By Sergei Gogin

Abstract:

In the age of the Internet, today’s Russian young people are not a monolith. While many seek material wealth and career success, putting off starting a family, they are divided among numerous subcultures. This article presents the opinions of many young people in their own words. The Ulyanovsk-based author interviewed local youth and others in the Volga city where Lenin was born and which now is more closely associated with the aviation industry. The city gained attention in early 2018 for a viral video produced by young cadets at a local institute that came to symbolize the limits of state intervention into private life.

Russia’s Youth Today

The current generation of Russian young people spent the majority of their lives, or even their whole lives, living under one national leader and for many that fact determines their individual life position. They had to adapt to that situation as a necessity. Some call it stability and are ready to participate in the political activity organized and approved by the authorities, focusing mainly on building their careers. Others see the current situation as stagnation and join the opposition movement, demanding change. A third group is intrinsically apathetic: they prefer to lose themselves in artistic pursuits, the Internet, or personal and professional development. This group is introverts and, if they rebel, it is within themselves or in the best case “in the kitchen” as in Soviet times. Today they are labeled “Generation Crimea” or the generation of “loyal pragmatists.” At the same time, the Russian youth are part of a global Generation Z, immersed in the epoch of the Internet and gadgets. They are slowly coming of age to be hedonists and conscious individualists, looking for material success and varied forms of leisure.

These general characteristics became apparent in five focus groups conducted in Ulyanovsk for this article. Interviewees included visitors to the Jarmusch Film Club, participants in the Crossroads English conversation club, fourth-year students studying public relations at the Ulyanovsk State Technical University (UlGTU), members of the region’s youth government, and members of Ksenia Sobchak’s campaign. This text also draws on interviews with additional experts and individuals. Unless otherwise noted all quotes are from conversations conducted by the author with residents of Ulyanovsk.

Two Groups

“This generation in general is variegated, but I would divide it into two categories,” said Sociologist and head of the Department of Political Science, Sociology, and Public Relations at UlGTU Olga Shinyaeva. “The first group includes those who study for a long time, take their time looking for their social niche, spend a long time adapting to life and only then start their career. Their parents must have sufficient material resources to provide for their kids while they decide what they are going to do.

The second group does not rely on their parents and seeks to live based on their own resources. They seek to quickly find their place and already start working when they are university students, either as waiters or in other low-level positions. They get little from their education and learn more from the practical sphere (if they are lucky). Typically, given their modest academic backgrounds, they do not achieve success quickly. They don’t read a lot of books. This second group is constantly growing.”

Internet

The main educational, entertainment, and social resource for young people is the Internet. Specialists note that teenagers spend a large part of their lives on-line. Several hours a day in front of the screen or with their tablet deprives them of traditional interactions with their peers or the need to make the kind of decisions necessary for adult life.

“For many of them, everything that goes on around them takes them away from what happens in their computers and phones,” Andrei Leshvanov, 30, a biology and chemistry school teacher said about his students. During each recess, kids play games on their phones, look at pictures on Instagram, and check the news on Vkontakte. I noticed that the majority of my students from 5th to 11th grade are not interested in anything in particular or are interested in many things, but only superficially, and generally what is connected to their games. I don’t know any interested in politics, the environment, or history.”

Aleksandr Revyakin, 27, is an electrician by training, but works as a freelancer in the Internet. He thinks that social life was better before the Internet. “It was easier to find people. They gathered in one and the same places and you could find someone either here or there. Now everyone has a cell phone but you can’t find them anywhere.”

“Yes, we are the information generation. We communicate through the internet rather than in person,” said Daria Belikova, a fourth-year student at UlGTU majoring in public relations. “To a certain extent this is imposed on us and we adjust to it, but I prefer personal interactions.”

“We are a bridge generation between the two eras, linking the pre-computer generation, people who did not have telephones, but did have television sets, and the people of the completely computerized generation, which we likely will not understand in the same way that our grandfathers do not understand us with our gadgets,” said Anton Ibragimov, a classmate of Belikova’s.

Individualism

The new generation of Russians is distinguished by expressing its individualism and focus on its own interests. Despite the fact that the majority of them are part of various subcultures or, in a wider sense, solidarities, these people do not form a crowd. Even when they join a protest demonstration, it is not from a feeling of collectivism, but due to their personal choice. “When today’s young people join a group, there is no dissolution of loss of their individuality,” Elena Omelchenko, the head of the Center for Youth Research at the Higher School of Economics, told the journal Ogonyok (#13, April 3, 2017).

“Of course, I am interested in what will happen to the country during Putin’s next term,” said Anastasia Zakharova, a fifth-year student at St. Petersburg Humanities University. “But for me there are more meaningful things than Putin: I have found my life’s work in philology. It would be great to focus on this my whole life and abstract myself away from politics”.

Private practice Psychologist Nadezhda Strunnikova, 33, expresses concern for environmental problems: she signs petitions against exterminating the whales, dolphins, and polar bears, and contributes to animal shelters. But, for example, the fact that Vladimir Putin has been in power longer than Brezhnev does not bother her. She says that she has consciously distanced herself from politics because she does not want to participate in political games that work by rules unknown to her. “Otherwise, I will not have time for myself or my development.” She has not voted in ten years. “I don’t believe that my vote will change anything,” she explains. “My lack of faith evolved gradually. I don’t believe in the authorities or the government. I don’t believe that they want to change things to help people and not for their own personal interests. I see an endless flow of bureaucrats and paper in the education system, in fact bureaucracy has become its main objective, and this is frustrating.” Strunnikova motivates herself with the simple joys of life: “There are many: birds, a ray of sun light, a good book, and a cup of well-brewed coffee.”

Pragmatism

The rising generation is not romantic. Rather, it is a generation of pragmatists. A survey conducted by the Political Science and Sociology Department at UlGTU among youth 16 to 30 years old (Nov.–Dec. 2017, 488 respondents) showed that the leading values in this group include material well-being, a professional career, and education. The least important were self-sacrifice (living for others), legality, and taking the initiative (entrepreneurship). Such values as honestly living life or a clean conscious were not high priorities. Researchers explain these choices by pointing out that the current generation was born in an epoch of cardinal changes when their parents were adapting to new economic conditions and concentrated on earning enough to live.

“My parents have two kids including me. When I was growing up I did not have expensive toys, but I wanted them,” said Ibragimov. “We lived simply, but we had enough food to eat. Now I want my kids to have everything, including a good education and health care. Therefore I don’t plan to start a family before I turn 35, until then my career is the most important thing for me. I want my wife and child to live in a comfortable home, but I won’t have that kind of income until I am 35 years old.”

Belikova does not plan to have a family before reaching 30. “A modern woman should not only have children and make a home, she should stand as an individual and a specialist. You can start a family after testing yourself in various spheres and find a place in life and work.”

Sociologists confirm: young Russians, like their Western peers, study longer, marry later, and put off having children. Scholars suggest rethinking the concept of adolescence and prolonging it until the age of 24. Today’s young people are more infantile and are not in a hurry to leave their parents’ home if they are more comfortable there.

Conformism, premature conservatism, a desire for safety, and rejecting the kind of rebellion which is so natural for young people are the characteristics of a generation which sociologists have identified in surveys and in-depth interviews. These “correct” young people are closer to the typical “man in the street”: they do not want to throw off the fetters of tradition; instead, they want to find their place in the system and benefit from it. Additionally, they understand that a change in the rulers of Russia, with its characteristic belief in a charismatic leader and preference for authoritarianism, will not likely happen soon.

“Surveys conducted at the turn of the century showed that material well-being at some moment fell off the list of top priorities; at that time, the top priority for young people was self-realization,” according to Sociologist Olga Shiniaeva. “Now material well-being and high incomes are at the top of the rating of values. They want to establish themselves and earn well.”

“They see that there are people in this system who earn big salaries and want to participate in dividing up the pie,” Aleksei Leshvanov says of his students.

Mariinsky Gymnasium student Aleksandra Zvonova, 17, does not consider herself a member of Generation Z, but calls herself an “old lady.” “People of the old order educated me, my romanticism is autodidacticism. I understood that trying to raise Russia from the ruins is senseless. I want to be a lawyer, but I don’t want any other position besides being a judge. I know that the judiciary is an extremely hermetic corporation, but it is easier to make one’s way there. Maybe if I become a good judge, I will be able to change the system from within.”

Former restaurant manager Sergei Sergeev, 30, supports the campaign of Ksenia Sobchak, but for purely pragmatic reasons: he is concerned about the general drop in incomes and an inability to find well-paid work. “I would agree to leaving the authorities in place permanently under the condition that I felt an increase in income concretely in my pocket,” he said.

Art Manager Pavel Soldatov, 32, connects young people’s conformism to the development of entertainment services: “Today there are places to go clubbing, but you need money to support yourself in a comfortable, intelligent atmosphere and keep up with trends as much as possible.” Young Russians generally are not rebels, but loyalists and pragmatists, who understand that being politically active today is not safe. The example of Boris Nemtsov shows them that political activity and charisma could cost you your life. In today’s Russia it is possible to receive a big fine or a long prison term even for reposting something on social media. Judges tend to apply article 282 of the Criminal Code, which prohibits inciting hatred and enmity, liberally.

Protest

Against this background, public expressions of disagreement and attempts to counter the system draw attention. One example was the all-Russian rally against high-level political corruption, “He is not Dimon to us” organized 26 March 2017 by opposition leader Aleksei Navalny. The series of protest marches was announced after Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation published research alleging that Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev had corrupt ties. Observers pointed out that high school students across the country participated in the event. “The first post-Soviet unimplicated generation” publicist Dmitry Oreshkin called these people. No one anticipated that such young people were capable of going out on the street, but it happened and Oreshkin, in one of his articles, explained why: “They came of age in the 00’s with that era’s economic growth, rising from the knees, and infinite perspectives, which seemed completely natural, deserved, and unlimited. … But already three years now something is not right. It is not clear why. Their parents have less money. They have fewer opportunities. Their chances have faded. The television propaganda has somehow become haggard…”

A good test of this generation’s love of freedom came with a recent incident at the Ulyanovsk Institute for Civil Aviation that went viral inside Russia and abroad. Freshmen students recorded a video clip of themselves dancing in their underwear, suspenders, and uniform caps grotesquely parodying the video by Italian DJ Benny Benassi “Satisfaction,” while illustrating daily life in their dorm. Without the knowledge of the creators, the video ended up on-line. The rector of the institute Sergei Krasnov compared the students to “Pussy Riot, who profaned a cathedral” and accused them of insulting the honor of their profession and threatened to expel them. Commissions from the ministry and the Volga Transportation Prosecutor’s office visited the institute. Ultimately, the students were not expelled from the institute, but they were issued a rebuke. That mild punishment was only possible due to the wide-spread support the students received. Ten of thousands of people signed internet petitions demanding that they be allowed to continue their studies. Flashmobs appeared spontaneously around the country. Students at other institutes filmed similar videos and posted them on-line. Even pensioners from St. Petersburg took part.

The vast majority of the comments in the internet argued that there is no sin in a group of healthy young people having a good time, especially at home, while interfering in their personal lives would be a sign of totalitarianism. “That the support was expressed in analogous parodies shows that the students hit a nerve,” Sociologist Omelchenko told the internet publication Ulgrad. “Maybe a subtle, hidden message of this performance was a demonstration of the right to one’s body and free time, a personal, private, apolitical part of life.”

“Even if you serve the state, you have the right to a private life and this right is guaranteed by the constitution. This is what aroused the uncontrolled rage among the defenders of state morality,” according to publicist Andrei Arkhangelsky, who described the incident as “a real conflict between the modern and the archaic, a conflict of cultures between the worlds of freedom and commands.”

Conclusion

Even as Russia’s contemporary younger generation has common characteristics and value orientations, it is not monolithic: while young nationalists call for removing Article 282 of the Criminal Code, their better off peers coordinate youth projects initiated by the authorities. Russian youth are Generation Z in the era of Vladimir Putin’s one-man rule, collapsing democratic freedoms, and increasing pressure on the opposition. But as the examples here demonstrate, through the conformism and political loyalism periodically elements of hidden protest appear.

“We are a generation born in the wrong place and the wrong time,” according to fourth-year UlGTU student Anatoly Spirin. “The main idea for us is to be free to do what we want. We don’t accept limits, but there are limits in politics, in education, in the social sphere, and it bothers us. We want to fight this and know what should be—here we have the examples of the Western countries. But we can’t do anything. We presumably are a freedom-loving generation, but closer to 30–40, more traditional values start to appear—starting a family and everything that goes with it. Over time our values are leveled and soon we will become like our parents, comforted by the idea of stability. What did the story of the aviation students show us? They are also young, like us, and also do not tolerate limits. The internet flashmobs in their support is the last chance to show that we still have a civil society. The typical instrument of civil society— street demonstrations—has been lost. Therefore the internet video is the last chance to announce “Listen to those of us in the rotting dormitory and our underwear.”

About the Author

Sergei Gogin is an independent journalist in Ulyanovsk.

Voter Turnout and Electoral Mobilization in Russian Federal Elections

By Inga Saikkonen

Abstract:

Electoral turnout has generally been higher in Russian presidential than parliamentary elections. Yet, there are remarkable differences in turnout levels between and within the Russian subnational regions. Electoral turnout fell dramatically in the 2016 Duma elections. Low turnout, even in the context of an overwhelming victory for the incumbent, can delegitimize the electoral result and signal dissatisfaction among the population and thus mobilizing voters to the polls is likely to be one of the key challenges for the Russian authorities in the upcoming 2018 presidential elections.

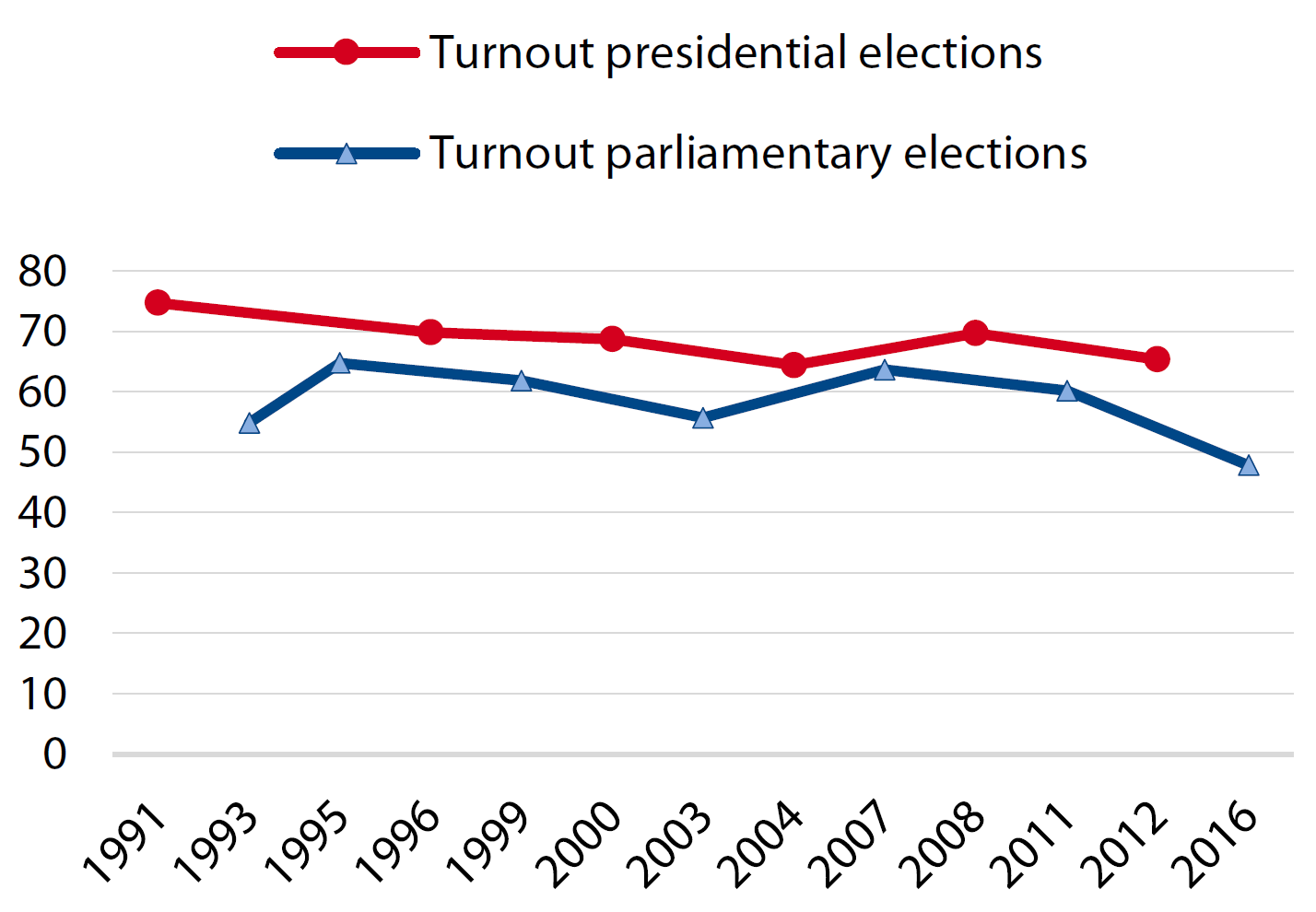

Turnout Patterns in Russian Federal Elections

Electoral turnout has traditionally been higher in Russian presidential elections than in other types of elections, such as the parliamentary elections. Figure 1 shows the aggregate electoral turnout in Russian presidential and parliamentary elections between 1991 and 2016. Electoral turnout in presidential elections has fallen somewhat since the first, “founding” elections in 1991. The competitiveness of both the Russian presidential and Duma elections has also declined considerably since the early 2000s. Evidence from many democracies shows that the closeness of the elections is linked to higher electoral participation rates, as this can incentivize the voters to participate and increase the “get out the vote” efforts by political parties (see, e.g., Geys 2006). In contrast, in Russia, the increasing predictability of the federal elections has not been reflected in overall electoral participation rates. The nationwide electoral turnout was around 65.3 per cent in the 2012 presidential elections, which Vladimir Putin won comfortably with 63.6 per cent of the votes.

Overall, turnout in parliamentary elections has generally followed the patterns in the presidential elections, and the turnout trends in presidential and parliamentary elections (which were held close in time until 2016) have tracked closely with each other over time. However, in the 2016 Duma elections turnout fell quite dramatically to only 47.8 per cent, representing over a 12 percent point drop from the 2011 elections. It was also the lowest nation-wide turnout rate in federal elections since 1991. This suggests that the Russian authorities need to exert considerable efforts in driving up electoral turnout in the upcoming 2018 presidential elections.

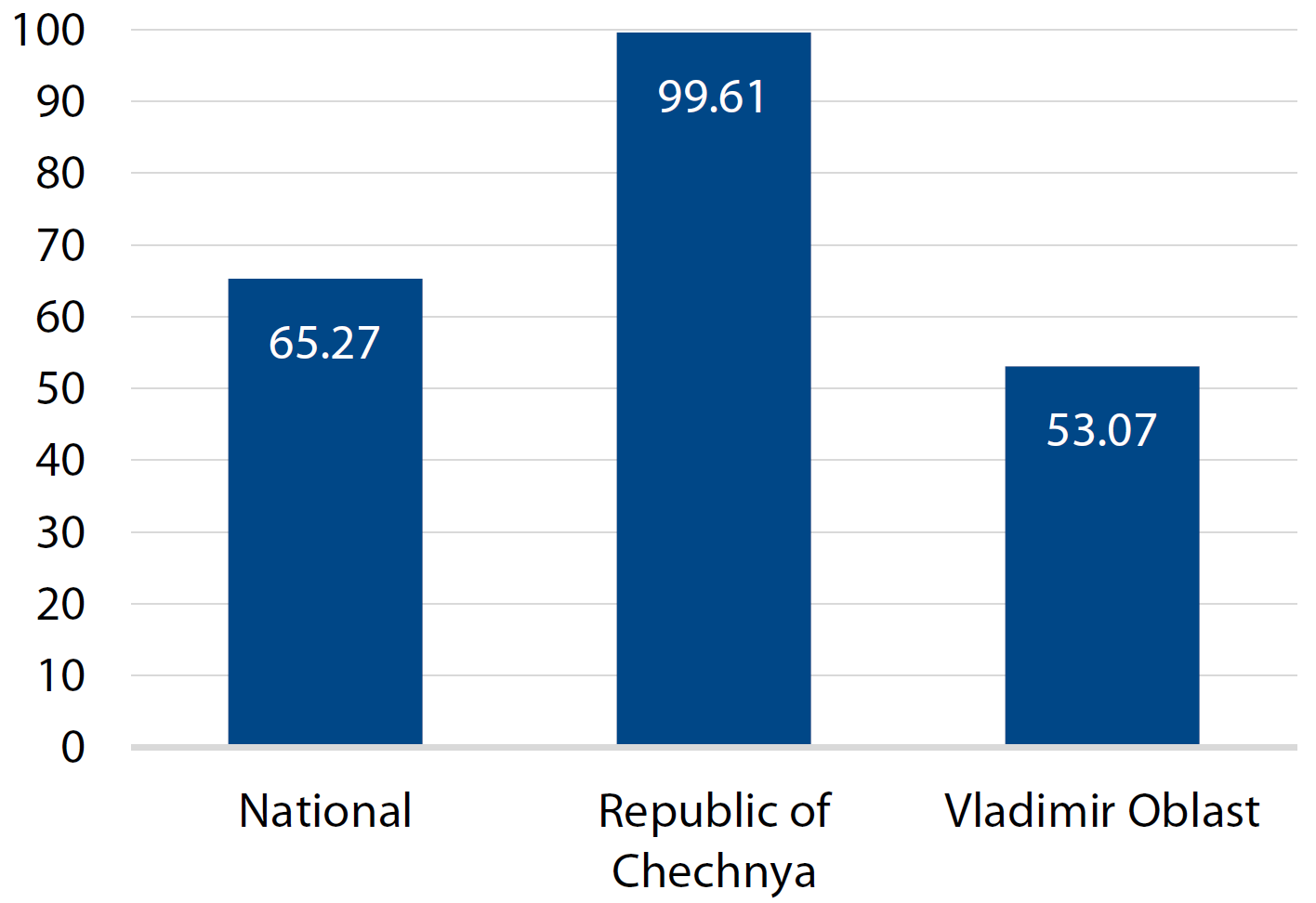

Yet, the aggregate national turnout figures mask considerable within-country differences in electoral participation rates in Russia. Although geographical variation in electoral turnout is common in many countries, the differences between the Russian subnational regions are striking by international comparison. As Figure 2 shows, in the 2012 presidential elections, the highest regional turnout rate was recorded in the Republic of Chechnya, which at 99.6 per cent resembled Soviet electoral results. In contrast, in many other Russian regions only just over half of the electorate participated in the elections. The lowest regional turnout rate, 53 per cent, was recorded in Vladimir Oblast, located in the Central Federal District. The difference between the highest and lowest regional turnout rate was thus a remarkable 46.5 percentage points.

Figure 1: Electoral Turnout in Russian Presidential and Parliamentary Elections, 1991 – 2016

In the 2012 elections electoral participation rates exceeded 90 percent in several ethnic republics, such as Daghestan and Tyva. Overall, studies have shown that regions with high concentrations of ethnic minorities, regions located in the North Caucasus, and natural resource rich regions tend to report the highest electoral turnout rates in Russian federal elections (see, e.g., White and Moser 2014).

Moreover, electoral participation rates in Russian federal elections can vary as much between the different localities (rayons) within the subnational regions as between these regions. (Rayons are local administrative units that are roughly equivalent to counties in the US.) In Russia, electoral turnout tends to be higher in rural areas than in urban centers (Clem 2006, Saikkonen 2017). Rayons inhabited largely by minority ethnic populations also report much higher turnout rates than other localities, and this is particularly salient in localities inhabited by “titular” ethnic minorities (such as the Tatars in Tatarstan) (White and Saikkonen 2016). These patterns are likely to reflect susceptibility to clientelistic targeting.

Figure 2: The Highest and Lowest Region-Level Turnout in the 2012 Russian Presidential Election (turnout in %)

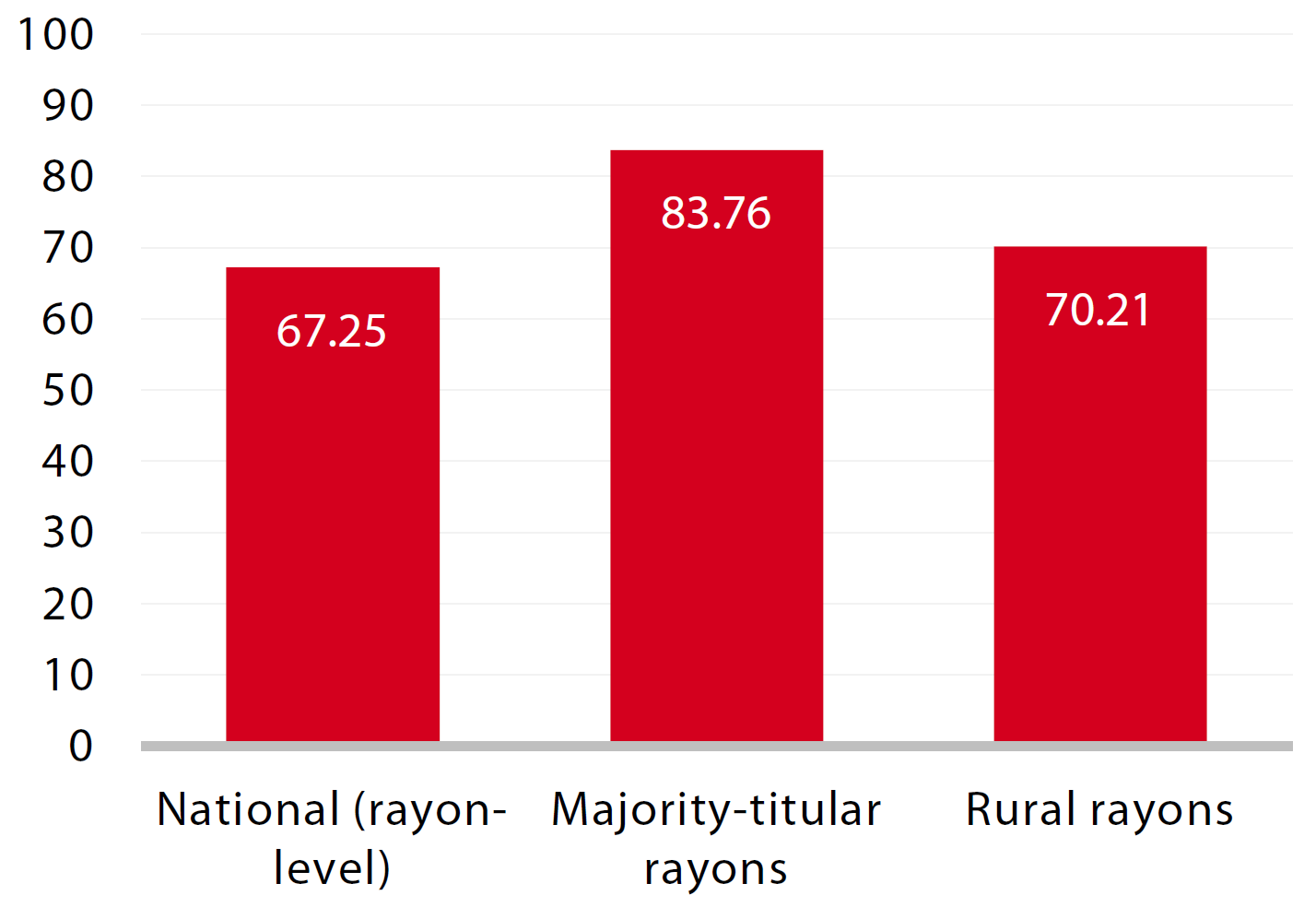

Figure 3 presents the differences in mean turnout levels in three types of rayons in the Russian 2012 presidential elections. As seen from the figure, rural rayons reported higher turnout than the nationwide average.

Figure 3: Rayon-Level Comparison of Turnout in the 2012 Russian Presidential Election (turnout in %)

This gap (around 16.5 percentage points) is even larger when turnout rates in rayons inhabited largely by titular ethnic minorities are compared to the nationwide mean. Thus the aggregate national turnout figures mask a very particular electoral geography in Russia, where electoral turnout tends to be much higher in rural and minority ethnic localities, as well as subnational regions with higher concentrations of ethnic minorities and regions located in the North Caucasus. These patterns are likely to reflect the targeting of electoral manipulation as well as electoral clientelism. Indeed, studies have shown that incidents of electoral manipulation tend to be higher in certain ethnic minority regions and the North Caucasus (Goodnow et al. 2014, Mebane and Kalinin 2010).

Electoral Mobilization in Electoral Autocracies

Elections in electoral authoritarian regimes, such as contemporary Russia, tend to be predetermined affairs that rarely pose a threat to the ruling regime’s power. Yet these kinds of elections still present other types of strategic dilemmas for the authorities. A key dilemma is how to maintain “decent” electoral turnout levels in non-competitive elections. Turnout mobilization through the means commonly used in democracies, such as by the media and political parties, can be risky in electoral authoritarian regimes, as these methods may also bring opposition supporters to the polls. Electoral autocracies benefit from the political apathy of opposition supporters, and therefore seek to keep the elections as devoid of “real” political campaigning as possible (see also Reuter 2016). Yet, the “boring” and non-programmatic character also lowers voters’ genuine incentives to participate in the elections.

However, low turnout, even in the context of an overwhelming victory for the regime, can delegitimize the electoral result, and signal “hidden” opposition among the population (Magaloni 2006). Therefore electoral autocracies commonly engage in “selective turnout mobilization,” that is, mobilizing specific sectors of the population to the polls through clientelistic appeals, such as state-dependent and socio-economically vulnerable sets of people (see, e.g., Blaydes 2010, Saikkonen 2017), while keeping the context of the elections as non-programmatic as possible. These population sectors are also often reliant on state-controlled media (especially state TV) for their political information (Kynev, Vakhshtain et al. 2012).

Electoral Mobilization in Russia and the 2018 Presidential Elections

The 2016 Russian parliamentary elections saw a considerable drop in turnout levels, and opinion poll data indicates that these trends may continue in the 2018 presidential elections. According to a survey by the Levada Center that was conducted in December 2017 only “30 percent of the respondents ‘definitely’ intended to vote, and another 28 per cent declared that they were ‘likely’ to go to the polls” (Gelman 2018, 3).

The Russian authorities have sought to invoke greater public interest in the elections by bringing in fresh faces to the ballot, such as the Communist Party candidate Pavel Grudinin and the candidate of the Civic Initiative party, Ksenia Sobchak. The incumbent President Putin remains very popular, and a part of the electorate will undoubtedly turn out to vote out of programmatic preferences. However, it is also likely that the pressures to ensure “high-enough” turnout levels will also intensify the selective turnout mobilization efforts in the upcoming elections. During the previous federal elections electoral mobilization efforts have targeted state-dependent sectors of the population, such as workers in state-connected firms and university students, or socio-economically vulnerable sectors of the population, such as pensioners or rural residents (see, e.g., Kynev, Vakhshtain et al. 2012, Frye, Reuter et al. 2014).

Turnout mobilization efforts have also been linked with the use of two types of “non-standard” voting in previous Russian federal elections, that is, voting at the workplace or at the university with an “absentee ballot” and “mobile voting,” that is, voting outside of the polling station with a mobile ballot box (see, e.g., Kynev, Vakhshtain et al. 2012). The 2012 presidential elections saw the highest totals of these types of voting to date when over 10 percent of the votes were cast by either absentee or mobile ballots. Electoral results can also be augmented by outright electoral fraud, such as the falsification of final vote counts or ballot box stuffing (see, e.g., (Mebane and Kalinin 2010)). The uncontested and predetermined nature of the upcoming Russian presidential election means that the authorities are under increasing pressure to drive up the official turnout figures.

Bibliography

- Blaydes, L. (2010). Elections and Distributive Politics in Mubarak’s Egypt. New York, Cambridge University Press.

- Clem, R. S. (2006). “Russia’s Electoral Geography: A Review.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 47(4): 381–406.

- Frye, T., O. J. Reuter and D. Szakonyi (2014). “Political Machines at Work: Voter Mobilization and Electoral Subversion in the Workplace.” World Politics 66(2): 195–228.

- Gelman, V. (2018). “2017 Year in Review: Russian Domestic Politics.” Russian Analytical Digest (213).

- Geys, B. (2006). “Explaining voter turnout: A review of aggregate-level research.” Electoral Studies 25: 637–663.

- Goodnow, R., R. G. Moser and T. Smith (2014). “Ethnicity and electoral manipulation in Russia.” Electoral Studies 36: 15–27.

- Kynev, A. V., V. S. Vakhshtain, A. Y. Buzin and A. E. Lyubarev (2012). Vybory Prezidenta Rossii 4 marta 2012 goda: Analiticheskiy doklad. Moscow, Golos.

- Magaloni, B. (2006). Voting for Autocracy, Hegemonic party survival and its demise in Mexico. New York, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Mebane, W. and K. Kalinin (2010). Electoral Fraud in Russia: Vote Counts Analysis using Second-Digit Mean Tests. Paper presented at the MPSA Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, 2010.

- Reuter, O.J. (2016). “2016 State Duma Elections: United Russia after 15 Years”. Russian Analytical Digest (189).

- Saikkonen, I. A.-L. (2017). “Electoral Mobilization and Authoritarian Elections: Evidence from Post-Soviet Russia.” Government and Opposition, 52:1: 51–74.

- White, A. C. and R. G. Moser (2014). “Voter Turnout in Russia: A Tale of Two Elections—1999 and 2011.” Paper presented at the MPSA Annual Conference, Chicago, IL, 2014.

- White, A. C. and I. A.-L. Saikkonen (2016). “More Than a Name? Variation in Voter Mobilization of Titular and Non-Titular Ethnic Minorities in Russian National Elections.” Ethnopolitics Advance online publication.

About the Author

Dr Inga Saikkonen is a postdoctoral researcher at the Social Science Research Institute in Åbo Akademi University, Finland. Her research focuses on comparative democratization, electoral authoritarian regimes and electoral behavior.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.