Military Conscription in Europe: New Relevance

22 Apr 2016

By Matthias Bieri for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published as CSS Analyses in Security Policy, No. 180 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

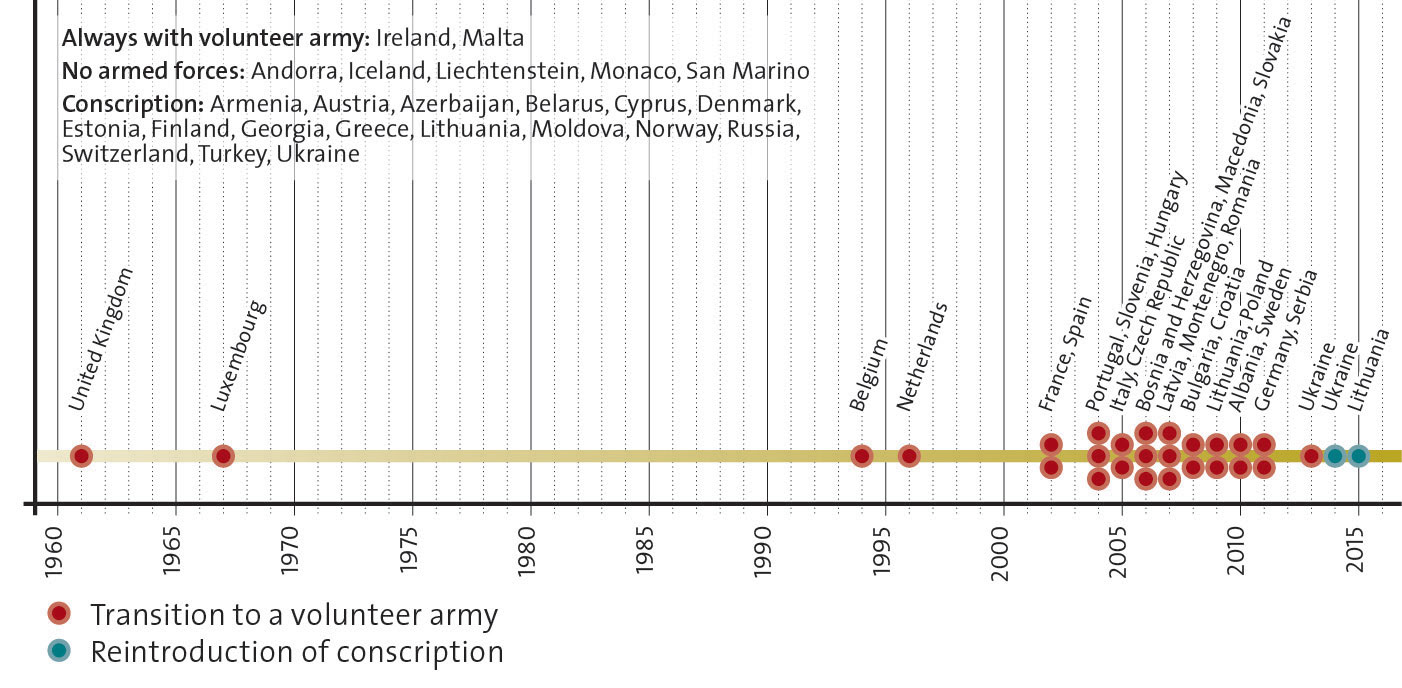

Is the Ukraine crisis bringing about a revival of conscription in Europe? After 24 countries ceased to practice conscription between 1990 and 2013 and for a certain time only 15 adhered to the model, two countries have recently re-introduced the draft – Lithuania and Ukraine. The justification offered for this measure was obvious: Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its intervention in eastern Ukraine. Lithuania also raised its defense budget from .78 per cent of GDP to 1.11 per cent of GDP between 2013 and 2015. In other Eastern European countries, but also in Sweden, debates began on the reintroduction of conscription and the defense readiness of the armed forces.

In Western Europe, too conscription has once again become an issue; however, the context is a different one and is marked by societal issues. In France, for example, following the attack on the editorial offices of satire magazine “Charlie Hebdo” in January 2015, some commentators lamented the loss of the service national, which was ended in 2002, and its integrative and didactic function. Due to this perspective, the debate took a different direction than those in Eastern Europe or Scandinavia: A number of notable politicians proposed a general community service for women and men without an obligation to do military service.

The reintroduction of conscription is thus once more an option due to considerations of military necessity in the foreign-policy sphere and considerations of state and social policy. However, the former solely gained popularity in Eastern and Northern Europe. In Western Europe, even under the new conditions of geopolitical tension, volunteer armies are in principle a suitable means of territorial defense. It is thus safe to say that here, domestic motives predominate.

In recent years, the European armies have been reduced in size to adapt them to new mission profiles and smaller defense budgets, lessening the need for recruits. Switzerland’s armed forces, too, are facing a 50 per cent reduction in numbers. Since 73 per cent of the Swiss voting population favored retaining conscription in 2013, there will be no changes in this form of national defense. However, an adaptation of the recruitment format is conceivable (see "Conscription in Switzerland" below).

Figure 1: Changes in form of national defense in Europe (click to enlarge).

Why (abolish) conscription?

The trend towards abolishing conscription in the past 20 years has had a number of causes. In the geopolitical détente after the end of the Cold War, mass armies were superfluous in Europe, while peacekeeping missions and foreign interventions became more important. Most countries refrain from deploying conscripts in such conflicts. Moreover, service periods have been growing shorter even as technically advanced armed forces require increasingly higher training standards. Many countries have therefore switched to volunteer armies, aiming to professionalize their forces and raising overall operational readiness. This allows them to use their resources in a more targeted and efficient manner in preparation for the most likely mission scenarios.

The end of conscription was also hastened by a shift in societal values. After the military threat had vanished, it became increasingly difficult to convey to citizens the purpose of this forced service – politicians could thus win votes by promising to abolish the draft. Furthermore, NATO and EU accession, with all the security guarantees that entailed, also fostered the abolition of conscription. In the countries concerned, national defense is planned strictly within the parameters of the alliance; large-scale conscript armies are no longer seen as necessary.

It is worth noting, however, that some conscript armies have de facto long relied on volunteer recruits, and certain states, while continuing conscription or returning to this model, effectively refrain from tapping its full potential. For example, Norway expanded conscription to include female citizens in 2015. At the same time, however, only the fittest and most highly motivated part of a given year’s intake of men and women – no more than one sixth – are actually called up for military service. Therefore, the armed forces are effectively recruited from volunteers. In Denmark, conscriptions have long been reserved for those recruitment places that are not filled with volunteers. For several years, the number of Danish volunteers has also been sufficiently high to make recruitment of conscripts practically superfluous. This is also the model that Lithuania decided to follow in 2015, with the reintroduction of the draft limited to five years for the time being. In these cases, the draft serves to guarantee a sufficient pool of recruits for the armed forces.

The countries retaining conscription are motivated by considerations of state and social policy, but also by concerns over the expected cost of switching to an all-volunteer force. There is also the fear that a fully professional army would find it difficult to recruit new soldiers, or that it would mainly draw its recruits from the poorer social strata.

Moreover, it is mainly smaller countries that adhere to conscription, which allows them to maintain armed forces of a certain size. Moreover, country- and region-specific reasons are also always involved. For the countries of Eastern and Northern Europe, the main consideration is their proximity to an erratic and militarily superior Russia. Moscow, in turn, wishes to reduce its number of conscripts and abolish the draft altogether in the 2020s. Then again, there are states whose interests are under threat from unresolved conflicts in their neighborhood. This is why countries like Greece, Turkey, or Cyprus, as well as countries in the Caucasus and Moldova, maintain armed forces that are geared towards conventional warfare conducted under national autonomy. Non-aligned status, too, is a strong argument in the debates over conscription. Since no other country is obliged to assist non-aligned countries, maintaining a numerically impressive army makes sense. In Austria, Finland, and Switzerland, this argument is frequently involved in support of conscription.

Newfound appeal

For many years, the concept of conscription was regarded as a throwback. In recent months, however, numerous countries have revisited the pros and cons of the draft. In Poland, the opposition is in favor of bringing it back. In Romania, the draft is still on the books in wartime, and certain politicians wish to reintroduce it altogether. Sweden is debating the return of conscription, which was suspended in 2010. In France, Italy, and the UK, too, conscription has been debated in recent months. The newfound appeal of conscription is due to military considerations as well as political idealism. It is only where both arguments apply that the return of conscription seems likely.

First of all, threat perceptions in Europe have shifted since the annexation of Crimea by Russia and the beginning of the Ukraine crisis. A confrontation with the neighboring great power of Russia appears more likely again. Thus, several states have announced increases in their defense budgets. Others are working on building up their military reserves or have reminded reservists of their duty in case of conflict. In Sweden, even the idea of NATO accession is gaining popularity; currently, a majority of the population is in favor. In many places, conscription has also gained importance. Since it facilitates numerically greater armies, it is apparently a reasonable option for Russia’s neighbors with their comparatively small populations.

From a military perspective, however, the return of conscription in response to the threat from Russia must be questioned. For one thing, Russia’s military capabilities remain limited. Even after a massive arms build-up on the part of Russia, which will emphasize quality rather than quantity, most of the countries of Europe will not need to return to full conscription and the concomitant numerical increase of their armed forces. Additionally, the military starting position is not really affected much by conscription even in the countries that border Russia. However, for the Baltic states, conscription is of great symbolic importance, allowing them to demonstrate their willingness to defend themselves and assert their self-confidence. Ultimately, however, the numerically increased armies of the Baltic states can only serve to demonstrate determination and to delay any Russian attack until NATO forces can reinforce them. Whether this is militarily feasible and likely without a local presence of troops from other NATO states is a whole different question.

Secondly, attention is once again being given to the societal function of conscription, in Western Europe, too where the threat scenario has been largely unaffected by the crisis in Ukraine. In many countries, pundits decry an alleged sense of responsibility and of societal values. The conscript army as the “citizens’ school” is currently being nostalgically evoked in this context. In Italy in the summer of 2015, the Lega Nord announced it would introduce a bill to bring back mandatory military and civil service. In France, where an increasing fragmentation of society and a ghettoization of parts of society may be observed, some regret the abolition of conscription. The Paris attacks were attributed in some parts to a lack of intermixing between social milieus, with republican values no longer being promoted throughout society by way of the armed forces. According to opinion polls, 60 to 80 per cent of respondents would support the reintroduction of the draft. Even in the UK, discussions about conscription made a return in 2015 after Prince Henry made it known that he supported the idea. In 2011, after violent youth protests, the government of Prime Minister David Cameron had introduced voluntary community service for youths. At the time, a survey showed 77 per cent of UK citizens supported a mandatory service for young people.

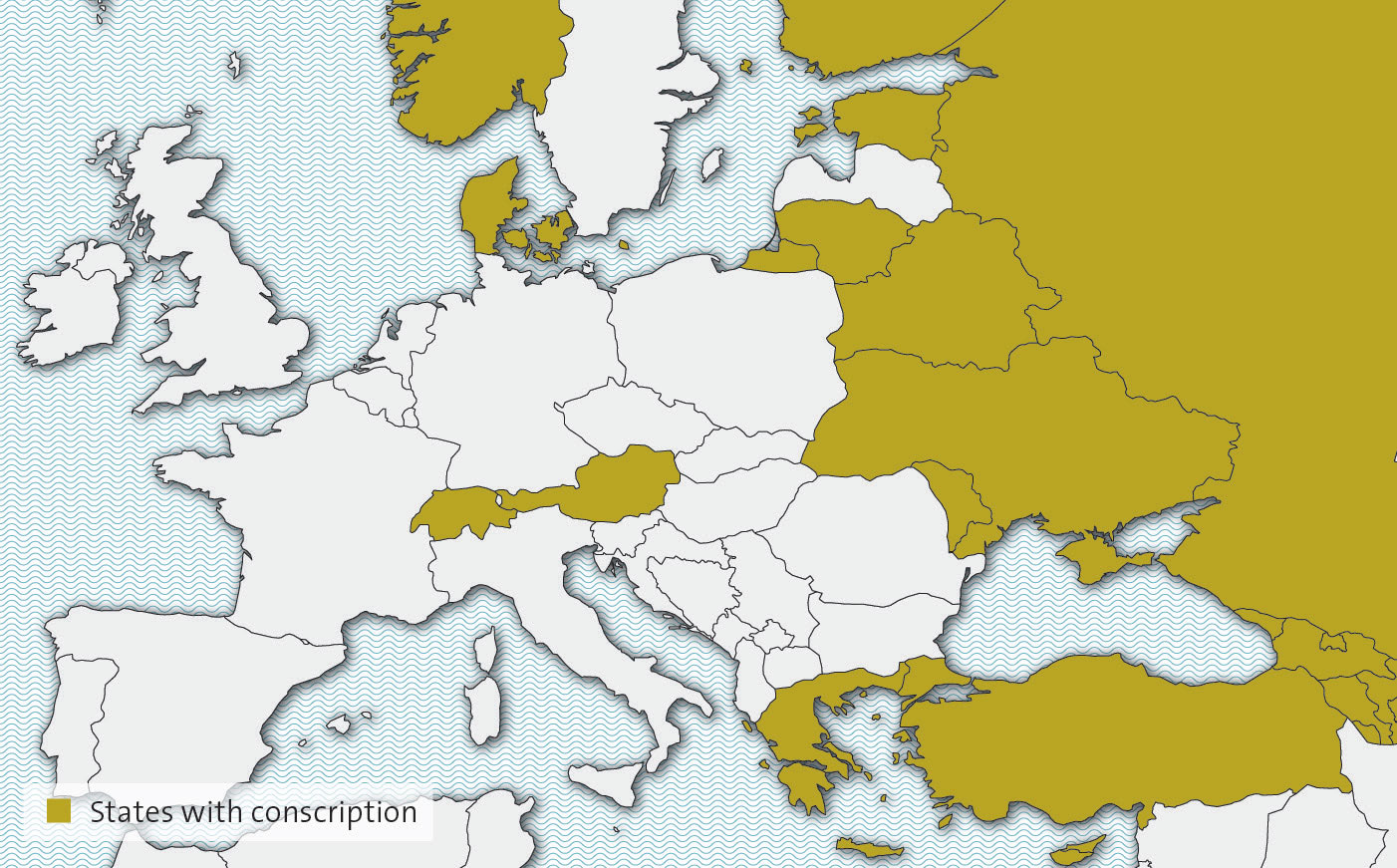

Figure 2: Conscription in Europe (click to enlarge).

The experiences of volunteer armies

For most European countries, the goal of creating smaller, more effective, and better-trained armed forces by switching to volunteer armies is still a desirable one. While territorial defense in the framework of NATO is regaining importance for many military forces, for the foreseeable future, this can also be achieved with volunteer armies. Also, despite the current averseness to military interventions in foreign countries, the capability to participate in out-of-area missions retains an important place in most military doctrines.

In some countries, higher individual motivation of soldiers is counted among the positive aspects of volunteer armies. Supposedly, these troops appreciate the realistic nature of training and the opportunity to be deployed overseas. In some countries, overseas tours of duty are actually especially popular among soldiers, due to the extra pay they receive. In numerous countries, military professionalization has actually improved the image of the armed forces. And finally, volunteer forces are often marked by a higher quota of female soldiers.

However, there are also difficulties involved with volunteer forces. Generally speaking, the transitional period has usually proven a major challenge. It is difficult to get the cadres of the old conscript army attuned to the new model of national defense. Some of the planning, for instance regarding volunteer numbers and costs, has proven over-optimistic. Certain armies have had to raise their attractiveness to find sufficient volunteers. Others are struggling with the quality of new recruits and officer candidates. However, in recent years, which were marked by the ongoing economic crisis, the problems with recruitment have markedly diminished, at least in terms of quantity. The high fluctuation rate remains a difficult problem, however. Many volunteers either depart after a short time or do not remain in the armed forces for as long as expected. This means a comparatively bad return on investment in training.

In most cases, the introduction of volunteer armies does not result in major economies in the state budget. While the number of soldiers is reduced, personnel costs in volunteer armies are significantly higher, as salaries must compete with those in the private sector and advertising costs are incurred. It is difficult to compare the costs of volunteer vs. conscript armies, since the mission profiles have shifted in the course of the reforms. It is also hard to assess the opportunity costs arising from conscript armies due to the absence of draftees from their workplaces. At the same time, the economic benefit of maintaining conscript armies is difficult to gauge.

Currently, the long-term consequences for state and society are unclear. One may speculate about a possible nexus between certain societal developments and the absence of conscription. However, there is no question that the abolition of conscription increases the distance between the armed forces and society. The belief that an all-volunteer force causes a militarization of foreign policy due to lower inhibitions about deploying armed forces remains unverified.

Difficult return

Despite the changed external parameters, a return to conscription is unlikely for most of the countries in question. This would largely be easy to do from a legal standpoint, as in most cases, conscription was not abolished altogether, but merely suspended. In those countries where it remains part of the constitution, the respective constitutional bodies could bring back conscription within a fairly short time.

However, the reintroduction of conscription would be difficult to implement in practical terms. In most European countries, the all-volunteer forces enjoy a great deal of domestic acceptance. In Lithuania, the reintroduction of conscription was announced without preliminary societal debate. In Western Europe, absent a societal consensus on the threat picture, reactivation would entail a massive potential for political and societal conflict. In certain Eastern European states, that consensus would be easier to achieve, not least due to the geographical proximity to Russia.

In addition to the societal challenges, there are also practical ones. Military infrastructure that was sold off in the transition to smaller volunteer forces would need to be rebuilt. Training structures, too, have been lost..

Alternative models

Some countries that retain the draft have adapted in recent years. Increasingly, conscription serves to ensure availability of a sufficiently large recruitment pool to meet target strengths. In Lithuania, conscription is designed to raise the number of active reserves. These, in turn, are to support the professional army in the case of a conflict. However, it appears that in 2015, despite the country’s return to conscription, no Lithuanian males will be forced to do military service against their will. The Lithuanian model is based on the recruitment targets being met with volunteers. If not enough volunteers are to be found, conscripts will also be called up. That does not seem to have been the case in 2015.

This model was adopted from Denmark, where all those subject to the draft must make an appearance for an information event and physical examination. However, conscripts are not called up unless the number of volunteers is insufficient. Among those fit for military service, a lottery draft determines who will have to serve in the armed forces. Those not selected by the draft do not need to perform any alternative service; however, they may be called up in a crisis situation. In 2014, 99 per cent of the men and women serving in the armed forces were volunteers, not least because of the attractive remuneration for soldiers. However, that quota cannot only be attributed to the higher number of volunteers. The Danish armed forces have been continuously downsized in the past years. Despite cutting the minimum service period to four months, they need less recruits.

In countries with all-volunteer armies, increasing measures are being undertaken to introduce young people to the armed forces. In certain countries, national service has been effectively reduced to one day. The Czech Republic has decided that from 2017 onwards, all males and females must report for medical examination at age 18, giving the authorities a better picture of the citizens available for recruitment in case of a conflict. In France, since the suspension of conscription, young people, men and women, have been forced to take part in mandatory information days to meet and learn about the armed forces.

A mandatory service might offer another alternative to military conscription. In many countries, such a system was effectively already in place before conscription was suspended. In Germany, for example, there were no obstacles to choosing alternative forms of service. In many discussions over mandatory service, equality is a core issue, with many believing that women, too, should be subject to mandatory service for the community. However, including females in this service duty would mean more resources were required to build up such a service system.

Conscription in Switzerland

In a 2013 referendum, 73 per cent of the Swiss population favored conscription. Nonetheless, the Swiss defense model is also facing changes. Currently, all Swiss men have to serve in the armed forces or the civil protection service, enroll for a substitute civilian service that lasts 50 per cent longer, or pay an exemption tax. In the upcoming transformation, the armed forces will be reduced to 100’000 soldiers. Obviously, this leaves just two choices – to shorten the service period or to lower the recruitment quota. The federal administration has appointed a working group specifically tasked with examining the possible distribution mechanisms for recruits. Fundamentally, the armed forces will continue to be prioritized in recruitment. In Switzerland, too, it is conceivable that conscription may be expanded to include women. Those unwilling to serve in the armed forces would still carry out alternative civilian service or pay an exemption tax. The armed forces would still be able to select the most motivated and physically fit citizens of every year for its ranks and thus reestablish the principle of draft fairness.