No 100, Caucasus Analytical Digest: Georgia´s Domestic Political Landscape

20 Dec 2017

By Tornike Zurabashvili, Tsisana Khundadze, Rati Shubladze, Ricardo Giucci and Anne Mdinaradze for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The four articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Caucasus Analytical Digest on 30 October 2017.

Georgia’s 2016 Parliamentary Election: One Year Later

By Tornike Zurabashvili

Abstract

This article reviews the results of Georgia’s 2016 parliamentary elections and assesses the post-electoral political development, focusing on the constitutional reform process and the dramatic changes in the opposition spectrum that followed the polls. The article concludes that despite the overall democratic conduct of parliamentary elections one year ago, the political implications in the aftermath have been worrisome. The ruling Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia party solidified its presence in the Parliament, while the liberal opposition spectrum has become fragmented and further weakened, losing its leverage for influencing everyday political decisions. The ruling party has also embarked on an ambitious and single-handed journey to transform the country’s constitution, including pushing through the widely denounced abolition of direct presidential elections and postponing its earlier plans to transition into a fully proportional parliamentary representation in 2020.

Introduction

On 8 October 2016, Georgia held its eighth parliamentary elections since it regained independence in the early 1990s. Georgia’s constitution, which holds the cabinet accountable solely to the 150-member legislature, makes parliament a pivotal player in its political system and the parliamentary elections a milestone event in the country’s political existence.

In Georgia’s mixed electoral system, voters elect 73 members of parliament in majoritarian, single-seat constituencies (more than 50 percent of votes are required for an outright victory). The remaining 77 seats are distributed proportionally in the closed party-list contest among the political parties that clear a 5 percent threshold.

The 8 October elections ended with an overwhelming victory for the ruling party. The Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia (GDDG) party garnered 48.68 percent of the votes and 44 mandates in a nationwide party-list contest. The GDDG party’s major contender—the United National Movement (UNM) party—finished with 27.11 percent of the votes and obtained 27 mandates. The Alliance of Patriots, the third party to enter parliament, narrowly cleared the five percent threshold and secured six parliamentary mandates. No other potential entrants have come close to the five percent threshold, except the Free Democrats who were just 0.37 percent short of passing the target.

The GDDG party also secured an outright victory in 23 single-seat electoral districts in the first round of elections and won almost all runoffs on 30 October, thus claiming a constitutional majority of 113 seats in the Parliament. Only one oppositional candidate managed to win a majoritarian contest (representative of the Industrialists party) along with one GDDG-supported but formally independent candidate (former Foreign Affairs Minister Salome Zurabishvili). The former—Simon Nozadze—joined the GDDG’s parliamentary majority group soon after the polls, increasing the ruling party’s parliamentary representation to 116 MPs.

A New Political Configuration

Despite some allegations of unlawful campaigning and several cases of violence, Georgia’s 2016 parliamentary contest was mostly peaceful, competitive and well-administered. Fundamental freedoms were generally observed; candidates were able to campaign freely, and voters were able to choose from a wide range of candidates, a significant step forward for Georgia’s young democracy.

The political consequences have been worrisome, however. The hopes for a multi-party parliament have been effectively dashed. The pre-electoral expectations for a close race between the incumbent Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia and the formerly ruling United National Movement appeared to be largely overstated as well; the UNM trailed far behind in the proportional contest and failed to narrow this difference in the majoritarian runoffs. As a result, the GDDG secured a constitutional majority in the parliament, which is a considerable step backwards from the diversity and balance of the previous parliamentary composition.

The Alliance of Patriots, the Georgian replica of contemporary European right-wing populist parties, cleared the 5 percent threshold and obtained six parliamentary mandates, leaving much older and more experienced liberal “third parties” far below the electoral bar and prompting a fundamental reshuffle of the oppositional spectrum. Soon after the elections, Irakli Alasania, leader of the Free Democrats, announced that he would be “temporarily quitting” politics, followed by Davit Usupashvili, the leader of the Republican Party and the former Parliamentary Chairman, who announced that he would be parting ways with the Republicans and starting a new oppositional political force—the Development Movement. Operatic bass turned politician Paata Burchuladze, whose State for the People party was considered to be a possible third party challenger to the UNM-GDDG duo, won just 3.5 percent of the vote before also leaving politics. One year after the elections, it remains unclear whether the three parties1 that won a cumulative 9.6 percent of support will survive their defeat and the subsequent high-profile defections.

The Big Schism

The United National Movement was beset by troubles as well. While Mikheil Saakashvili, the country’s exiled former president and the leader of the party, called for a boycott of the runoff elections and parliament, the Tbilisi-based party leadership preferred to enter the parliament and the majoritarian runoffs. Saakashvili lost the debate, and the party opted against the boycott, except in the city of Zugdidi where UNM’s candidate and Mikheil Saakashvili’s wife Sandra Roelofs refused to participate in the second round.

The UNM’s expectedly meager performance in the runoffs reignited intra-party frictions and gave the former president an upper hand in the debate. Disagreements emerged on a range of issues, from filling the vacant seat of the party chairperson to the date and scale of the 2017 party convention. The UNM’s decision to conduct the convention with 7,000 delegates, as Saakashvili wanted, did not end the crisis. The sides continued exchanging accusations, with the conflict particularly felt in social networks where sympathizers of Saakashvili challenged their numerically fewer opponents and accused them of trying to distance the party from Mikheil Saakashvili and its grassroots.

The four-month tug-of-war ended with the departure of several UNM party heavyweights, including former Parliamentary Chairman Davit Bakradze and former Tbilisi mayor Gigi Ugulava, released from prison in January 2017 after the Tbilisi Court of Appeal requalified the misspending charges against him. They announced that they would leave the party and establish a new political movement under the name of the European Georgia party.

This was not the first time the United National Movement had lost members of parliament; almost 20 lawmakers left in 2012, and more defected in 2015 and 2016. However, the party had successfully managed to minimize the negative consequences of these defections or at least managed to present the impact of such differences as of little importance. The remaining UNM leaders did exactly that this time as well; they commented on several members “defecting” from the party rather than the European Georgia-advanced “splitting” of the party in an apparent attempt to downplay the significance of the development. Despite their attempts, however, it is clear that the division has significantly affected the party itself and the overall political configuration of the country.

First, the UNM party lost a majority of its lawmakers and the Tbilisi-based leadership, reducing its parliamentary representation to six MPs and stripping the party of some of its most skilled party bureaucrats and opinion-makers. The victory of the less compromising faction under the leadership of Mikheil Saakashvili over its consensus-oriented rivals also signaled the beginning of the party’s transformation to a more vocal, protest-oriented movement, with the potential to solidify UNM’s traditional support base but repel disgruntled GDDG voters or third party supporters. The fact that the UNM incurred the electoral cost of the division was clearly demonstrated in the National Democratic Institute’s June opinion poll, where only nine percent (down from 15 percent in June 2016) of respondents named the UNM as “the party closest” to them, compared to 23 percent who named the GDDG (up from 19 percent in June 2016).

The split has been particularly hard for the European Georgia party and its leaders, whose constituency has never been as stable as that of Mikheil Saakashvili. The party has failed to win over the non-UNM oppositional vote, which could have opened up following the defeat and gradual weakening of liberal third parties. As a result, NDI’s July survey shows the party struggling to clear the five percent threshold (the European Georgia party is “closest” for 4 percent of respondents).

The New Constitution

Possibly the most significant political development in the aftermath of the 2016 polls is the constitutional reform process, which completes the country’s evolution towards a parliamentary form of government through introducing a number of important changes to the existing institutional arrangement.

The history of the Georgian Dream-led constitutional reform process dates back to 2013, a year after the Georgian Dream coalition won a decisive victory over the then-ruling United National Movement. The three-year tenure of the Constitutional Reform Commission, established to address “serious shortcomings” in the constitution, yielded no result. Lacking intra-coalition consensus and sufficient legislative votes to pass the proposed constitutional amendments, the Georgian Dream coalition backtracked on its plans to amend the country’s constitution.

The environment changed drastically in the aftermath of the 2016 parliamentary election. The GDDG, with a much larger parliamentary mandate, re-launched the constitutional reform process with the aim of “perfecting” the constitution. The 73-member State Constitutional Commission, consisting of legal experts and representatives of seven political parties, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations, was established on 15 December 2016 and was tasked with offering its official proposals by the end of April 2017.

The Commission endorsed the draft constitutional amendments with 43 votes to eight at its final session on 22 April, following four months of intensive, closed-door discussions and earning a “positive assessment” from the Venice Commission, Council of Europe’s (CoE) advisory body for legal affairs.

The Commission’s work and the subsequent public discussions were, however, marred by claims by the president and opposition that the ruling party aimed to craft a system that would solidify its hold on power. Dissatisfied with the composition of the Constitutional Reform Commission, the presidential administration rejected the Commission and publicly criticized the reform process on numerous occasions. As the commission neared the end of its work, seven opposition parties left the body, accusing the ruling party of wanting to cement its power through constitutional changes.

Proposed presidential elections through an indirect, parliamentary vote, the postponement of the introduction of the fully proportional electoral system to 2024 (instead of 2020 as initially planned) and the proposed rule attributing wasted votes to the winner in the proportional parliamentary polls (the bonus system) were particularly criticized.

Despite criticism and several failed attempts to resume political dialogue over the amendments, the parliament of Georgia approved the draft constitution in its third and final reading at its special sitting on 26 September 2017, with 117 lawmakers voting in favor and two voting against it. The United National Movement and the European Georgia boycotted the parliamentary vote.

When combined, the presidential and political party boycotts severely affected the constitutional reform process and undermined the public trust in the work of the commission and the overall reform process. It also affected the state of the country’s democracy: by adopting the draft of the new constitution without broad political participation, the ruling party reinforced the long-lasting tradition of single party-led constitutional revision processes and contributed to the erosion of the principle of constitutionalism with the potential to affect the country’s long-term prospects of democratic consolidation.

The manner in which the process was conducted also contributed to the widely held assumption that the constitutional reform process was aimed specifically at weakening the presidency of Giorgi Margvelashvili due to his acrimony toward the ruling party. The GDDG’s compromise that the implementation of the new mode of presidential election would start with the 2024 presidential election and thus not affect the upcoming 2018 election remedied the situation but failed to resolve concerns entirely.

The proposed bonus system, the postponement to 2024 of the introduction of the fully proportional electoral system and the abolition of electoral blocs have raised concerns as well, with opponents arguing that the move would serve further consolidation of the GDDG party’s grip on power and hinder smaller parties from entering the legislature. The ruling party’s pledge that it would allow the party blocs for the next parliamentary elections and abandon the bonus system from 2024 is indeed a positive but insufficient development for ensuring long-term party pluralism and equal distribution of votes.

Foreign Policy

The government has in general continued to pursue a broadly democratic agenda despite a number of controversial decisions in 2017, including the Rustavi 2 TV ownership dispute, the government’s crackdown on Fethullah Gülen-affiliated schools, and the mysterious disappearance and subsequent detention of Azerbaijani journalist Afgan Mukhtarli.

Regarding foreign policy, the orientation towards the West has continued despite the fact that the two ardently pro-Western political parties—the Free Democrats and the Republicans—are no longer in the Cabinet and the pro-Western opposition spectrum has weakened at the expense of its Russia-sympathetic alternatives, most notably the Alliance of Patriots. The country formalized visa-free travel with the Schengen area and secured a number of important mentions in U.S. government documents, including sanctions against Russia and the military budget for 2018.

EU and NATO integration has remained the GDDG party’s top priority, as underlined by Prime Minister Giorgi Kvirikashvili and other GDDG leaders on numerous occasions after the elections. This was particularly the case for the country’s EU aspirations, which the government has actively lobbied for at EU institutions and with member state governments.

The country’s diplomats continued engaging with their Russian counterparts in the Geneva International Discussions and the Prague talks, the two regular formats of dialogue, but no major breakthrough has been achieved in the relations between Tbilisi and Moscow. Fundamental differences on the status and the future of Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia and Moscow’s step-by-step political and military integration of the two regions have hampered any further progress in the bilateral relations between the two countries.

About the Author

Tornike Zurabashvili is Editor-in-Chief of Civil Georgia. Civil.ge is a daily news online service devoted to delivering quality news about Georgia. Published in three languages (Georgian, English, Russian), Civil.ge has a history of editorial and political independence.

The Public Political Mood in Georgia

By Tsisana Khundadze (CRRC-Georgia)

Abstract

Georgia’s population’s perception of the government’s performance and overall direction of the country’s development has fluctuated during the last several years. Individuals appear to be more positive toward the government and the country’s future immediately after elections, though these feelings fade over time. Considering that issues related to employment and the economic situation continue to be the top concerns for citizens throughout the years, it appears that individuals are more hopeful for positive change during election periods and become disillusioned after several months. The following article discusses national-level issues that people perceive as salient. It also follows individuals’ perceptions of the government’s performance and overall assessments of the country’s development over time, seeking the link between perceived issues of importance and the assessment of the government’s performance.

Introduction

Political life in Georgia stepped into a new phase after the 2012 parliamentary elections when, for the first time in independent Georgia’s history, the political power was passed from one party to another through elections. Five years and four national and local elections later, Georgian citizens continue to give the mandate to the party that promised to make the Georgian dream come true. While the ruling party changed in 2012, data shows that individuals’ perceptions of the most important national issues has not. What changed is the people’s perception of the government’s performance and the country’s direction. Nationally representative survey data1 from CRRC-Georgia and NDI-Georgia draw a picture of the dynamics of the public political mood in Georgia. Observed trends in Georgian public opinion resonate with the notion that people in democracies have more positive attitudes toward the government immediately after elections (Ginsberg & Weissberg 1978; Blais & Gelineau 2007).

During the past five years, there were some significant changes in economic and political terms in Georgia. The parliament adopted several pieces of controversial legislation and drafted amendments to the constitution that triggered extensive discussions in political circles (Transparency International-Georgia 2014 / Radio Tavisupleba 2017). Continued and fluctuating devaluation of the national currency has also raised concerns about financial stability in the country since the end of 2014 (Jandieri 2015 / Namchavadze 2015). On the other hand, significant advances occurred in terms of foreign relations. Georgia and the EU signed the association agreement in June 2014, and as of spring 2017, Georgian citizens can enjoy visa-free travel to the EU’s Schengen area countries.

Democracy

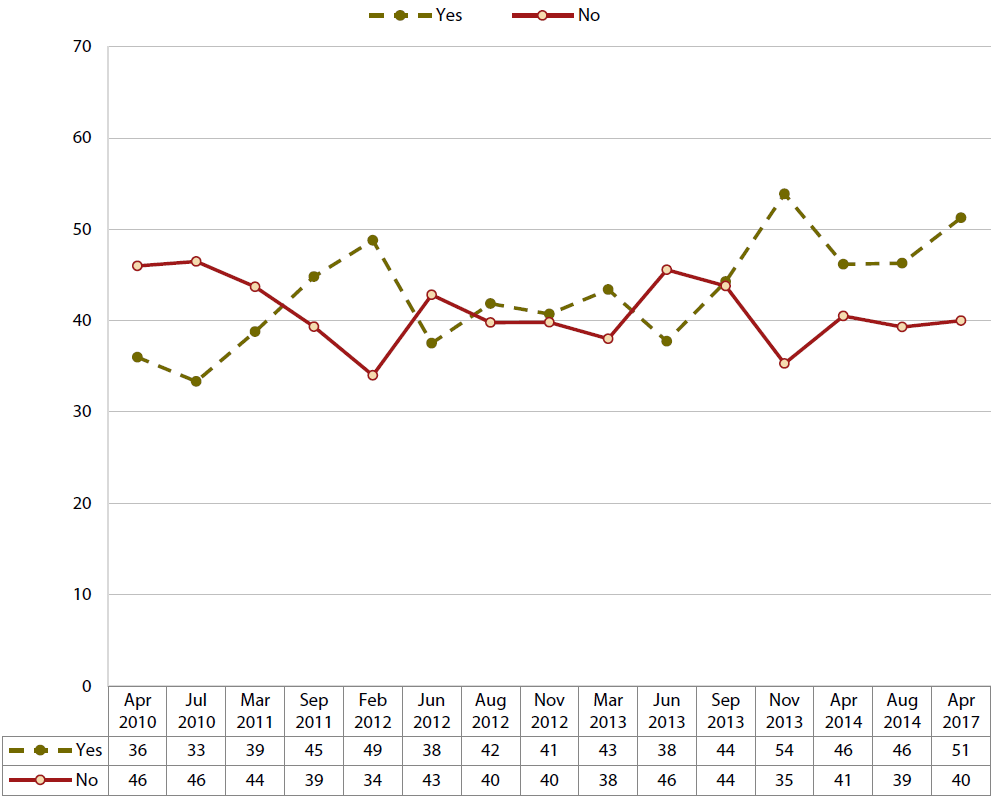

Individuals’ perceptions of Georgia as a democracy have been more or less consistent since the end of 2013, despite many changes in political life. According to data from the CRRC/NDI April 2017 survey, approximately half of the population says that Georgia is a democracy, while 40% think that it is not a democracy. The picture was slightly different before 2011, when the share of individuals who felt that Georgia was not a democracy was higher than the proportion of the population who stressed that Georgia is a democracy. Public opinion dithered between 2011 and 2013, until finally, at the end of 2013, the majority began to see Georgia as a democracy (See Figure 1 on p. 8).

Even though we cannot say with precision what individuals base their assessment on, we can speculate that they take various indicators of democracy into consideration. For example, when asked about the situation in the country in terms of freedom of speech in June 2017, 51% of the population indicated that the situation in the country is good. Positive opinions were stated by 35% of the population about free and fair elections and protection of human rights, by 32% about the rule of law, by 29% about citizens’ participation in public life, by 28% about curbing corruption, and by only 24% about government response to citizen concerns. Thus, for each of these criteria except for freedom of speech, the proportion of individuals who say that the situation is good is around the same as the percentage who say the situation is bad (in the case of freedom of speech, only 18% say the situation in Georgia is bad). Additionally, people’s perception of the condition in the country in terms of these criteria has not changed significantly since November 2015.

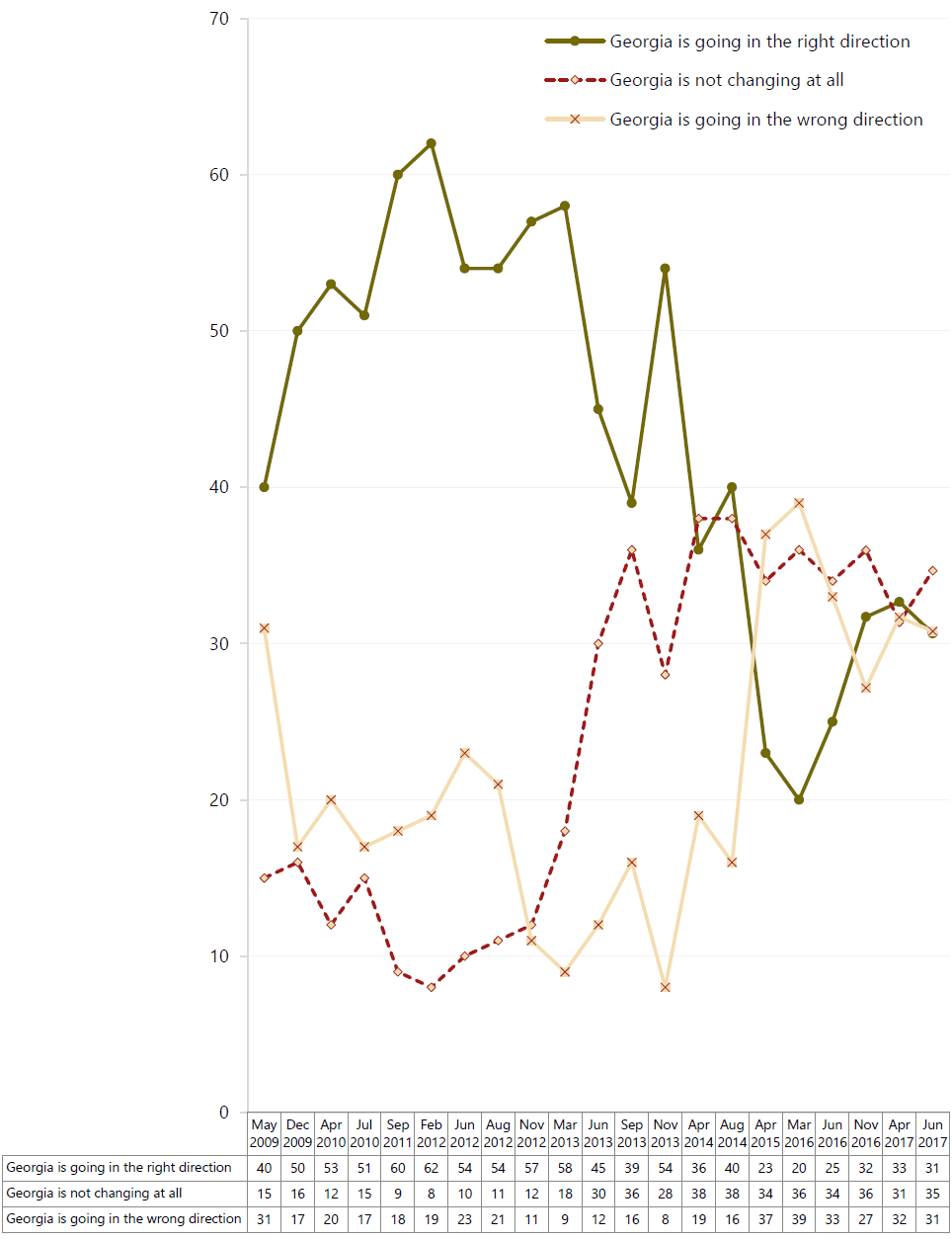

The Country’s Direction

According to the latest CRRC/NDI survey conducted in summer 2017, Georgia was split in three, with one-third of the population thinking that Georgia is going in the right direction, another third thinking that Georgia is going in the wrong direction and another third thinking that Georgia is not changing at all. While it might seem that this composition of public opinion is logical taking into consideration the processes in the country, historical data show that people were more optimistic about the country’s direction throughout 2009–2012 (See Figure 2 on p. 9). Before 2014, a larger proportion of Georgia’s population thought Georgia was going in the right direction. Throughout 2012, more than 50% of people claimed that the country was going in the right direction; beginning in April 2014, we see increasing trends for citizens who think Georgia is going in the wrong direction.

One important fact to consider is that little peaks in positive outlook are apparent shortly after national elections. The share of people who think that Georgia is going in the right direction started decreasing in the middle of 2013, with a sudden increase in November 2013 directly after the elections. The second peak occurred directly after the 2016 parliamentary elections, following another period of decrease in 2014 and 2015 of the percentage of people with a positive outlook on the country’s direction. This indicates that people have a more positive attitude shortly after the elections and that over time, the positivity decreases. It should be stressed that the positive peak was noticeably lower in 2016 compared to 2013.

Most Important National Issues

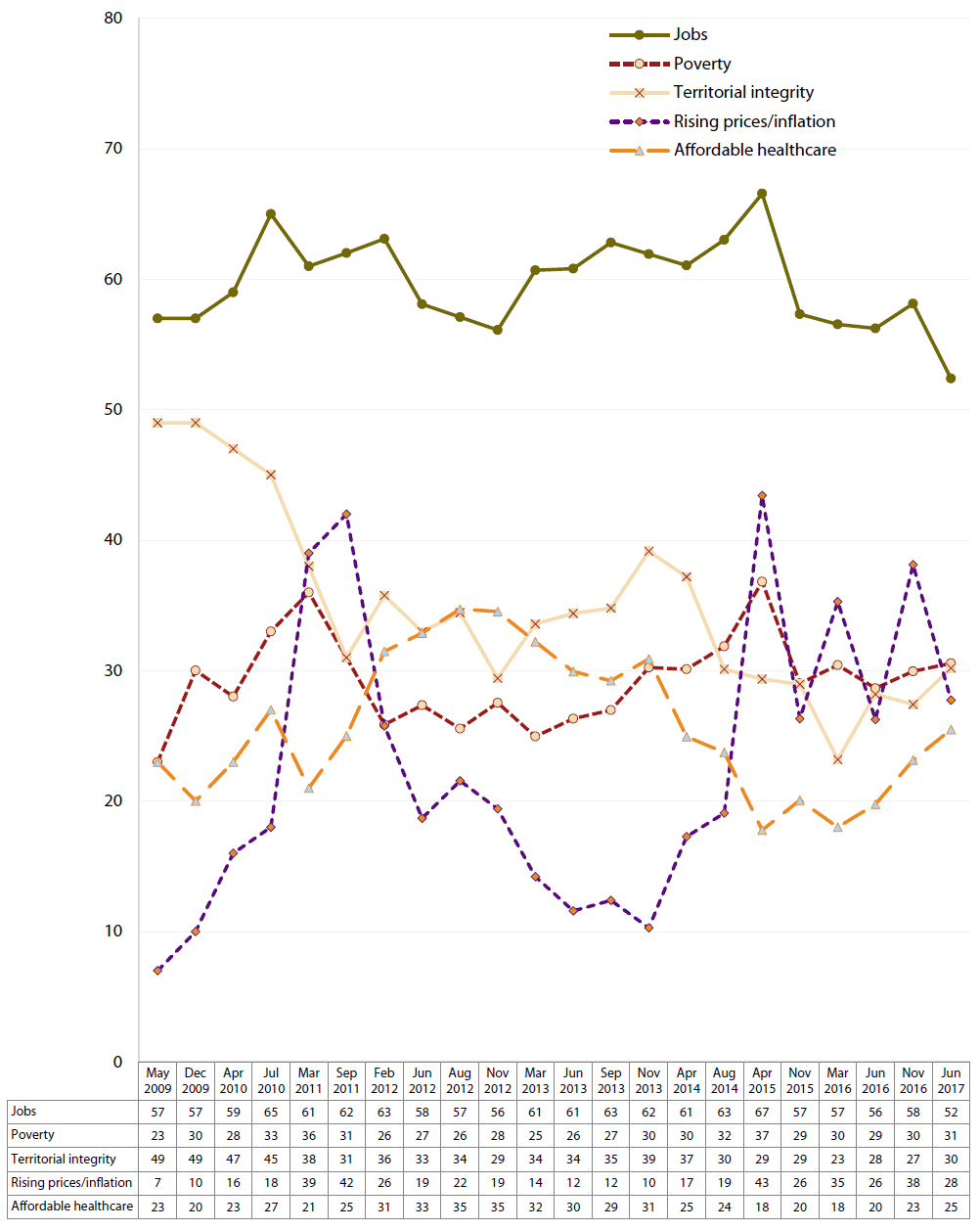

One thing that has not changed through the years is the list of national issues stressed by the population as being the most important. Employment has always been the number one issue, named by more than fifty percent of the population every time. Poverty, rising prices/inflation, affordable healthcare and territorial integrity have competed for second place throughout the years, with 25–35% of people naming them among the most important issues (See Figure 3 on p. 10). As we can see, four of the top five issues are related to economic situations.

Interestingly, issues related to political life, such as corruption, media independence, the court system, property rights, and human rights, have remained at the bottom of the list, and only a small percentage of individuals name them as important issues. One would expect more of these issues to be considered important based on people’s assessment of the situation in the country in terms of democratic development, but data show that economy-related issues are more pressing for most individuals. Moreover, issues such as NATO and EU membership are also named by only approximately 3–5% of people as the most important, even though the support for joining these organizations is high and has been high throughout the years2.

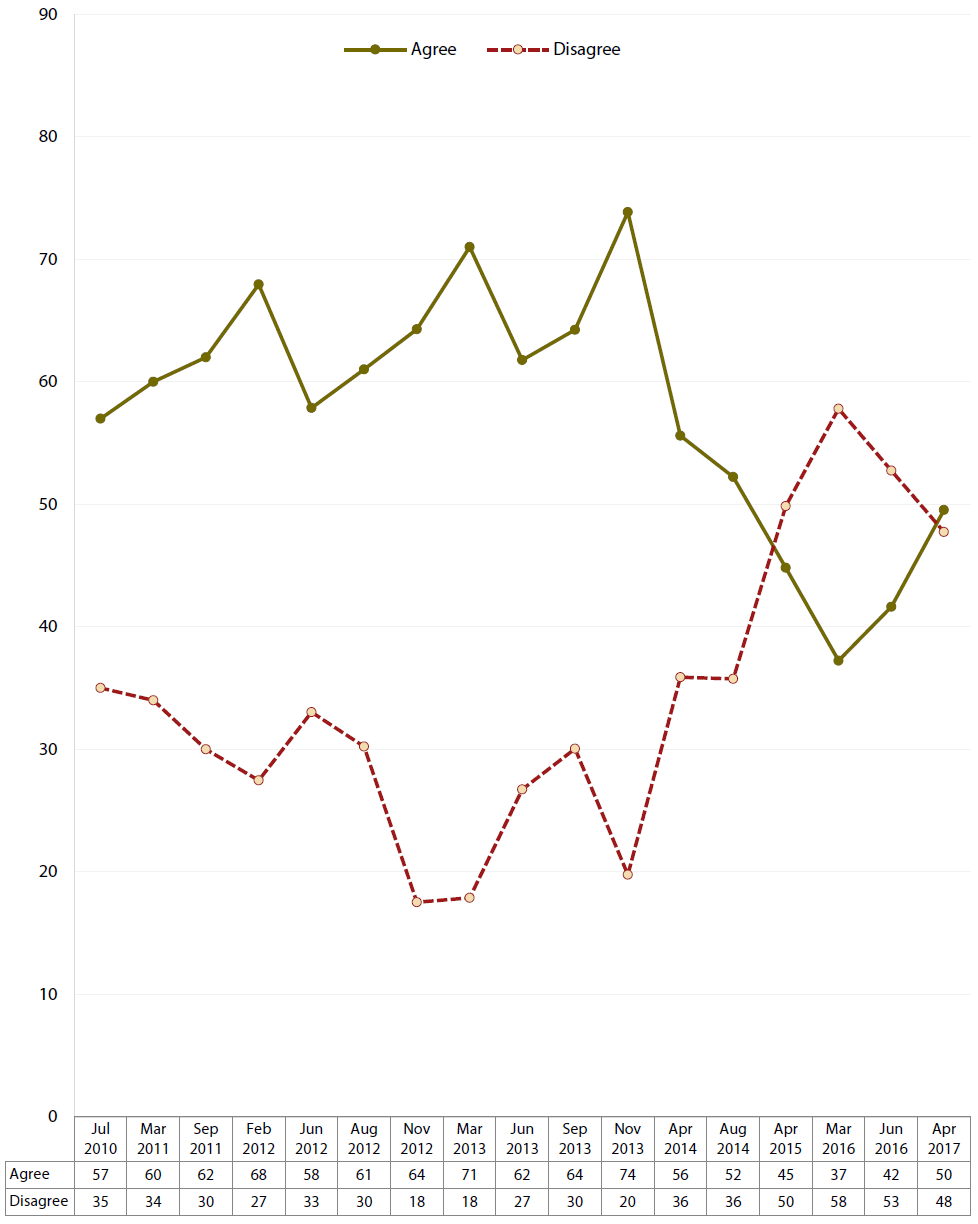

The Government’s Performance

While people’s concerns retain the salience and economic nature through the years, their perception of whether the government is making the changes important to them fluctuates much like the assessment of the country’s direction. In April 2017, the Georgian population was divided in two with half pointing out that the Georgian government was making the changes that mattered to them and with the other half disagreeing with such notions (See Figure 4 on p. 11). Historical data show that people’s opinion about the government’s activities started becoming less positive in 2014, when only 56% said the government was making important changes, compared to November 2013 when 74% said the government was making important changes. In 2016, for the first time since 2010, the percentage of people who think that the government is not making important changes actually exceeded the number of people who think that the opposite is true. However, people’s perceptions of the changes made by the government improved after the 2016 parliamentary elections. Again, even considering the overall decreasing trend in the share of people who think that the government is making the changes that matter to them, positive changes in attitudes are still apparent shortly after the national elections.

Little insight into what people base their assessment of the government on can be provided when looking at how people assess the performance of different ministries. According to data from the CRRC/NDI April 2016 survey3, the majority of the population rates the performance of different ministries as average or poor. Nevertheless, people note that the Ministry for Labor, Healthcare and Social Affairs and the Ministry of Justice are performing better than other institutions, while the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Economy and Sustainable Development, and Ministry of Finance rank the last on the list with twice as many people thinking they are performing poorly compared to people who think they perform well. This again points to people’s dissatisfaction with economy-related issues.

Discussion

The discussed tendencies illustrate that the Georgian public has a more or less clear understanding of where the country stands in terms of democracy and what important issues are. However, people’s perceptions of the direction in which the country is headed and whether the government makes relevant changes varies over time, with a more positive outlook directly after the national elections and decreasing enthusiasm after the post-election period passes. Similar tendencies of an increase in positive attitudes after elections has already been examined in other research conducted in the US and Canada. Ginsberg and Weissberg (1978) noted that people had more positive attitudes toward the regime, its leaders and the policy after the elections in 1968 and 1972 in the US. Blais and Gélineau (2007), on the other hand, found that satisfaction with the level of democracy in Canada increased significantly after the elections, although this increase was higher among people who voted for the winning party. Nevertheless, people who voted for the parties that lost or those who did not participate in the elections also expressed more satisfaction after elections than before elections (Blais & Gélineau 2007).

Possible explanations for the increase in positive attitudes toward the government after elections include the “participation effect,” implying that by participating in the elections, citizens’ levels of responsibility may increase as they have become a part of the decision-making process. Another possibility is that as a result of socialization in democratic regimes, people are more likely to accept the government elected by the majority even if they have not participated in elections. Another explanation could be related to cognitive dissonance theory, which points to the process of rationalization after making the choice, in this specific case, of voting for a certain political actor (Ginsberg & Weissberg 1978, p. 49). While any or all three of these propositions might be related to how public attitudes are formed after elections, it is important to see the similarities in the trends of the public’s political attitudes in Georgia and other democracies. Further research is needed to better understand the post-election change in public opinion in Georgia.

Conclusion

According to CRRC/NDI survey data, Georgian public opinion is divided on whether the country is developing in the right or wrong direction. While the government has made many changes in the past 5 years, the majority of citizens are not convinced that the government is making changes that matter to them. People keep naming the same economy-related issues as important. The public’s assessment of the situation of democracy remains more or less consistent, but the performance assessment tends to fluctuate. Historical data show that people are more positive directly after the elections and that the enthusiasm fades away over time. At the moment, we can only speculate about the causes for such tendencies, but at the same time, we keep in mind that such changes in public political mood have previously been observed in democratic regimes. Further investigation of the phenomena may offer some insight into the Georgian public’s political culture.

Notes

1 The data are available at http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/datasets/ as well as at https://www.ndi.org/georgia-polls

2 See http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/datasets/, https://www.ndi. org/georgia-polls

3 See http://caucasusbarometer.org/en/datasets/

Further Reading/Bibliography

Blais, A. and Gélineau, F., 2007. Winning, losing and satisfaction with democracy. Political Studies, 55(2), pp. 425–441.

Ginsberg, B. and Weissberg, R., 1978. Elections and the mobilization of popular support. American Journal of Political Science, pp. 31–55.

Jandieri, G. 2015, “What Has Happened with Georgian Lari?” 4liberty.eu <http://4liberty.eu/ what-has-happened-with-georgian-lari/>

Namchavadze, B., 2015. “The Effects of Depreciation of GEL on the Social-Economic Strategy Georgia 2020” <https://idfi.ge/en/the-effects-of-depreciation-of-lari-on-the-social-economic-strategy-georgia-2020>

Transparency International-Georgia. 2014. “New anti-discrimination law: Challenges and achievements” <http:// www.transparency.ge/en/blog/new-anti-discrimination-law-challenges-and-achievements>

Radio Tavisupleba, 2017. “Constitutional changes—the theme of autumn sessions” <https://www.radiotavisup leba.ge/a/sakonstitucio-cvlilebebi-sashemodgomo-sesiebis-mtavari-tema/28720276.html>

About the Author

Tsisana Khundadze holds a PhD in Psychology from Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University. She is a senior researcher at CRRC-Georgia and an invited lecturer at Tbilisi State University.

Figure 1: Is Georgia a Democracy Now?

Figure 2: In Which Direction is Georgia Going?

Figure 3: Most Important National Issues

Figure 4: Current Government Is Making Changes That Matter to You

Why Is the Turnout of Young People So Low in Georgian Elections?

By Rati Shubladze (CRRC-Georgia)

Abstract

The paper analyzes the different factors contributing to the generational gap between younger and older voters in Georgia. It shows that the lack of awareness and interest in political and specifically in electoral processes among young people largely explains this phenomenon. At the same time, several institutional factors, such as electoral campaign salience and specific legislation, also contribute to the low levels of youth participation in elections. Finally, the article proposes several practical steps, including the introduction of online and/or electronic voting and the emphasis of youth-related issues in electoral campaigns, that could help to increase the turnout of young voters in Georgia.

Introduction

A lack of interest in politics and low levels of political participation among young people are common not only in Georgia but also in many countries (Fieldhouse et.al. 2007). A number of complex issues are believed to explain this phenomenon, e.g., having little stake in society (Economist 2014) or preferring other types of activities (EUROPP 2013) to express one’s political and social views. The low levels of political participation among youth and their alienation from public activities, such as elections, have been matters of concern in representative democracies (Norris, 2003). Political parties, usually not mainstream and protest-oriented, see youth alienation as an opportunity to gain their support. During the 2016 parliamentary election campaign in Georgia, a minor political party, “New Political Center—Girchi,” released a commercial encouraging young people to participate in the upcoming elections1. The commercial appealed to young voters to change the current political situation, wherein political parties use populist promises in an attempt to attract older voters. In addition, the commercial claimed that younger voters needed to turn out to voting booths and have their say. Despite this, post electoral surveys revealed that a relatively small number of younger voters participated in the 2016 elections (Figure 1 on p. 15). This contribution argues that low levels of electoral involvement result from a combination of interconnected aspects, including systemic, institutional and individual factors. Furthermore, the article claims that by implementing a few practical steps, such as online and/or electronic voting and the application of more youth-oriented political campaigns, the turnout of young voters in Georgia could be increased.

Assessing Young Voters’ Involvement in Voting

This contribution was not able to use the official election data, as the Central Election Commission of Georgia (CEC) does not report voter turnout by age group. To estimate the turnout of young voters, this contribution uses reported rates of participation in elections based on CRRC/NDI polls conducted in June 2016, November 2016 and June 20172. Polling data provide the opportunity to deeply investigate the socio-economic background of the adult population (18 years old and over), as well as their preferences, attitudes toward elections and reasoning for voting or not voting at elections. However, using data from public opinion polls has its own limitations, and these should be kept in mind during analysis. Political scientists have identified that there is a considerable difference between self-reported voter turnout, as seen in survey findings, and official turnout. The most widespread explanation for this fact is social desirability bias, i.e., when respondents who did not vote are embarrassed to admit it (Holbrook and Krosnick, 2009). The same difference is observed when comparing official electoral turnout with turnout reported in surveys conducted in Georgia, including the CRRC/ NDI post-electoral survey. For example, according to the CEC, the voter turnout for the 2012 parliamentary election was approximately 60%3, but the survey conducted right after the election indicated an 86% turnout4.

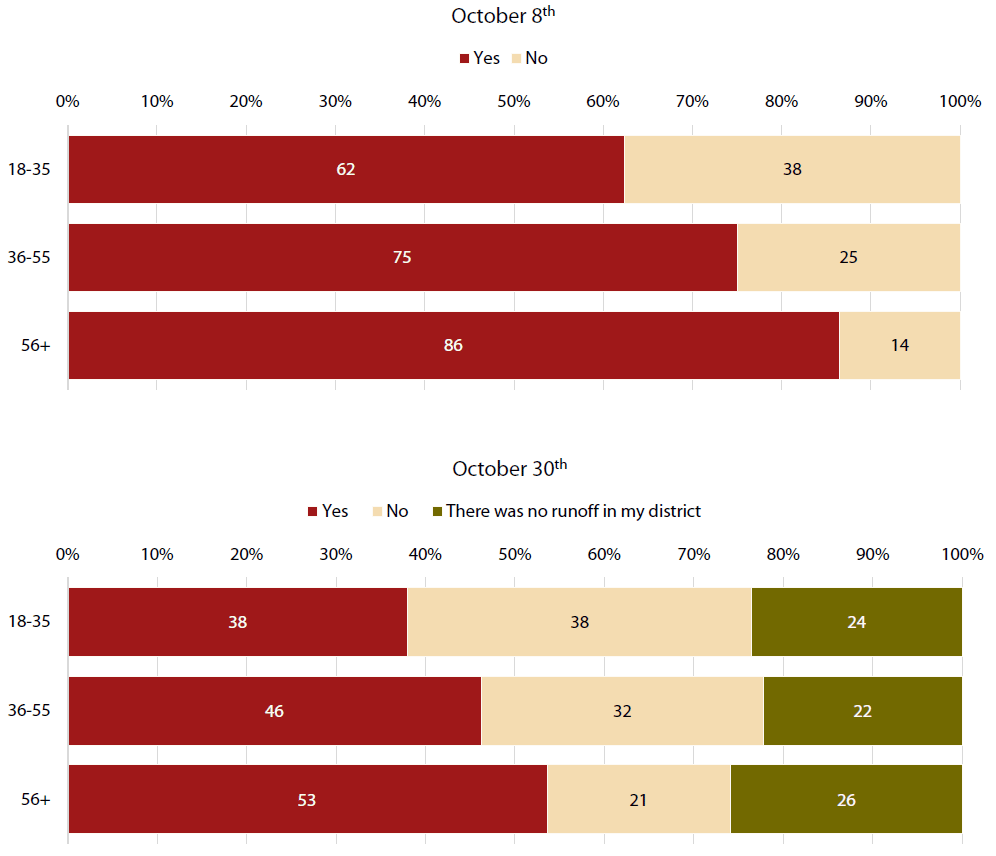

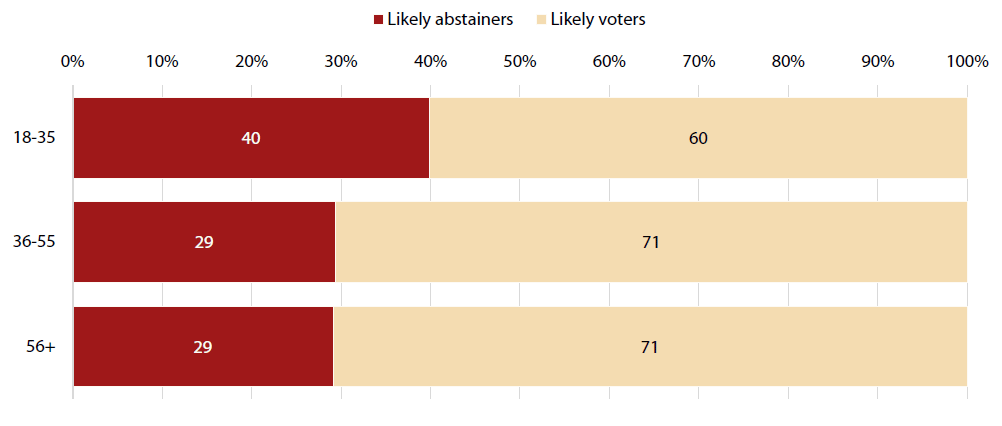

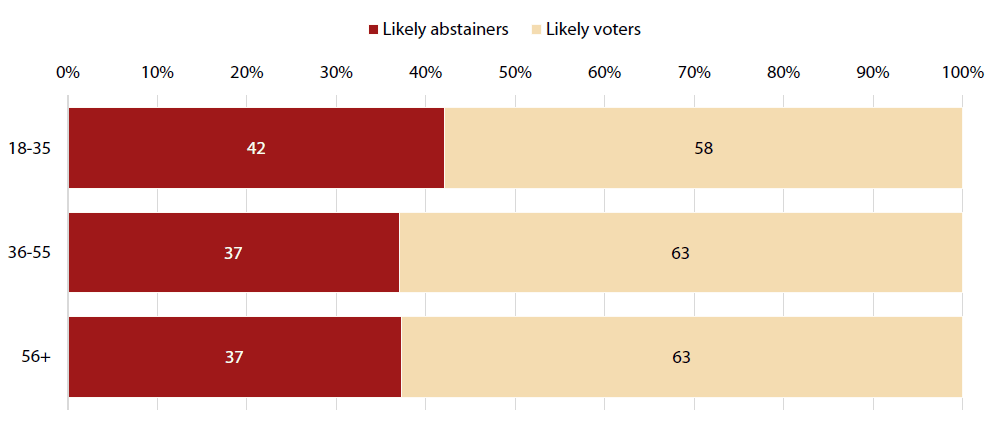

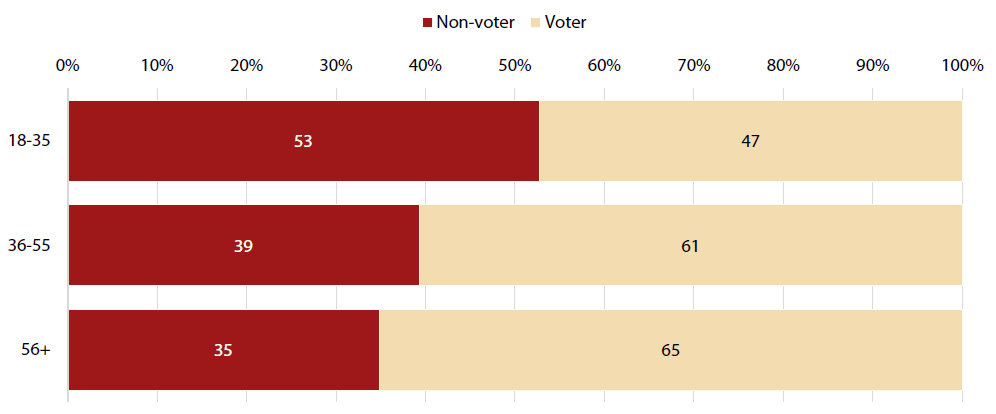

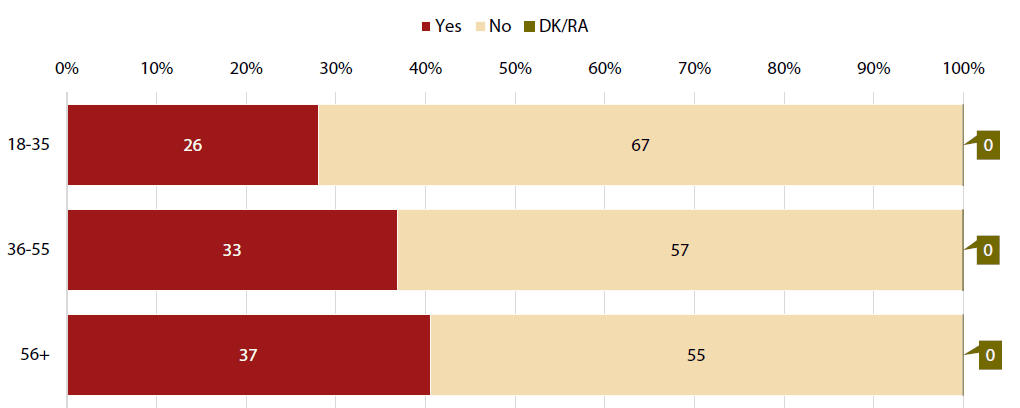

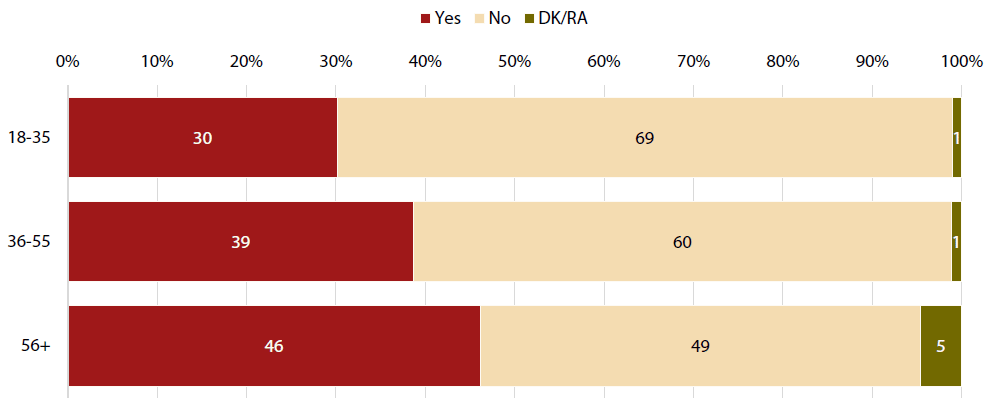

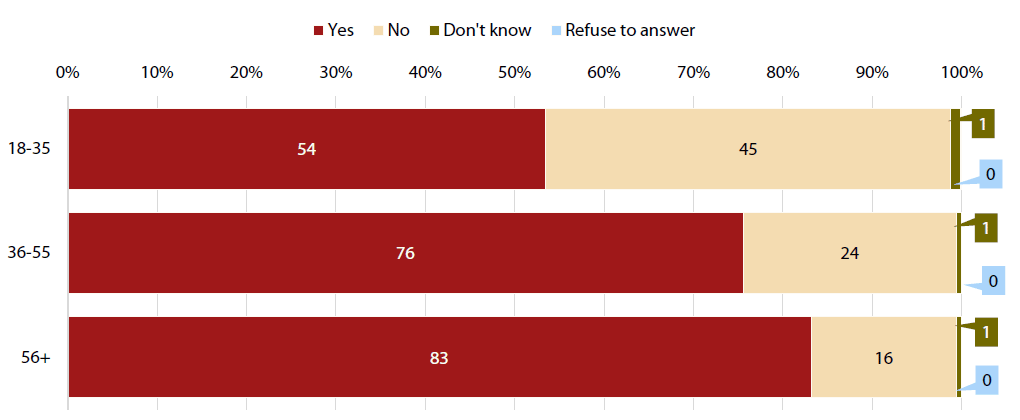

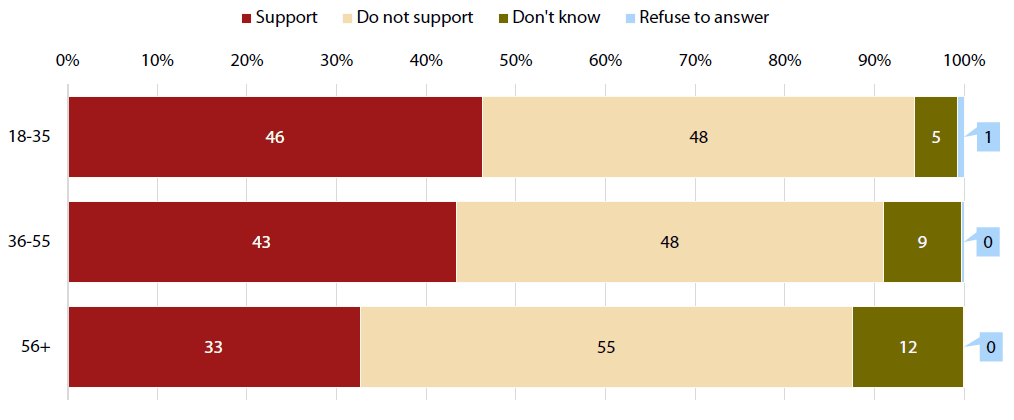

According to the results of the CRRC/NDI post-electoral November 2016 survey, there is a generational gap between voters in Georgia. Even accounting for social desirability bias, during both the October 8th parliamentary elections and the October 30th runoffs in 2016, voters who were between the ages of 18 and 35 were reported to be less active than older voters (See Figure 1 on p. 15). In the pre-electoral June 2016 and June 2017 surveys, younger voters also indicated relatively low levels of voting intention when compared to other generational groups (See Figure 2a and 2b on p. 16). Moreover, in June 2017, the CRRC/NDI pre-electoral survey also provided likely voter model5 variables to eliminate social desirability bias. However, the younger cohort again showed lower levels of voting intention than did older generations (See Figure 3 on p. 17).

Factors of Low Young Voter Turnout

To understand what factors can constrain young voters from casting their votes, this paper employs analytical tools to evaluate systemic, institutional and individual factors (Esser and De Vreese 2007). At the systemic level, overall historical and cultural traditions, particularly those related to the political culture and electoral traditions of the country, could influence youth turnout. Evaluations at the institutional level take into consideration “the structural context of political and media institutions,” i.e., how specific electoral laws and media coverage can encourage or discourage young voters to cast their votes. The individual level looks at the socio-demographic features of voters, such as their involvement in electoral processes and their knowledge of electoral procedures.

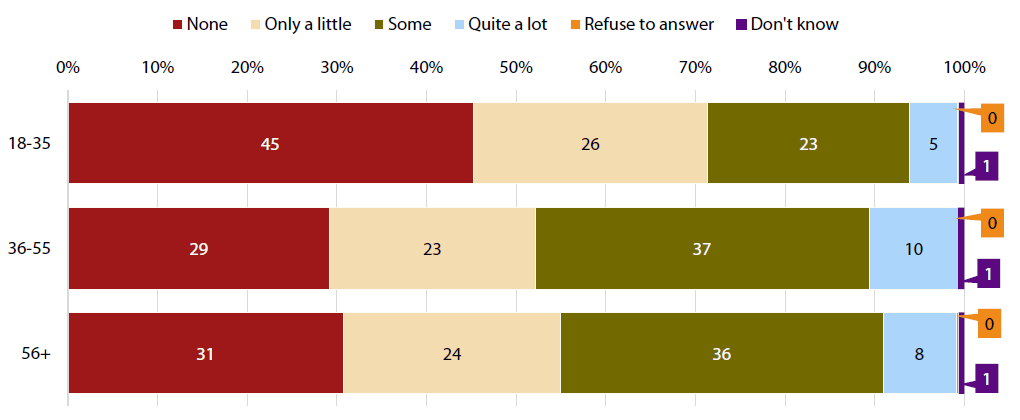

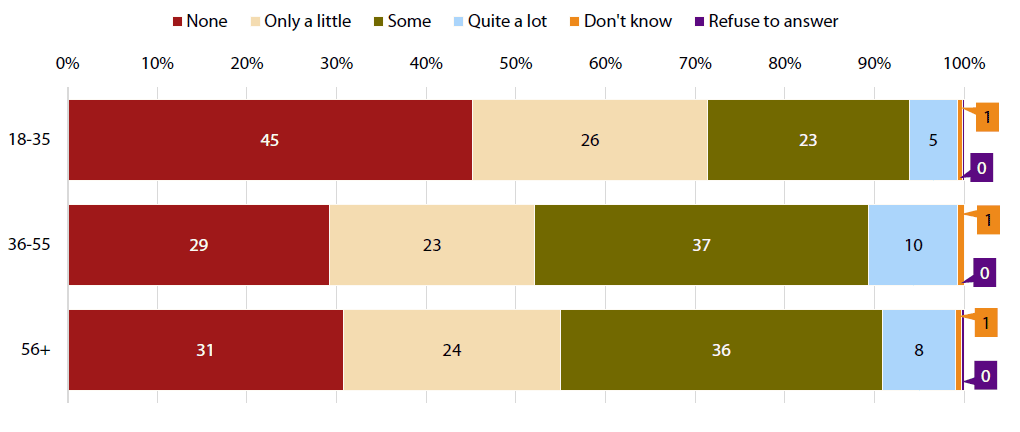

On a systemic level, the general lack of interest in politics could explain why young Georgians tend to stay at home and not vote. A number of surveys suggest that young people in Georgia are indifferent towards politics. For instance, those who are younger report discussing politics and current events with friends and close relatives less frequently6 than do those who are older. Many young Georgians also do not even know who the majoritarian member of Parliament from their constituency is7. The CRRC/NDI pre-electoral poll in June 2017 asked questions about an important ongoing political issue, namely, the draft of the Revision of the Constitution adopted by the State Constitutional Commission8. The results showed that young Georgians are less aware and less informed about the constitutional amendments than are older citizens (See Figure 4a and 4b on p. 17/18).

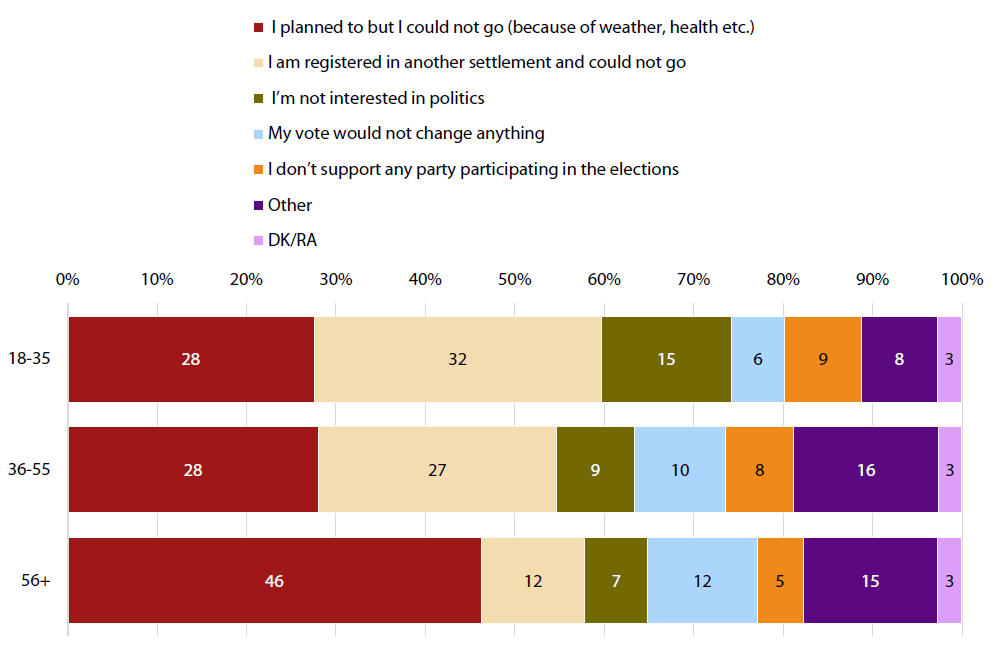

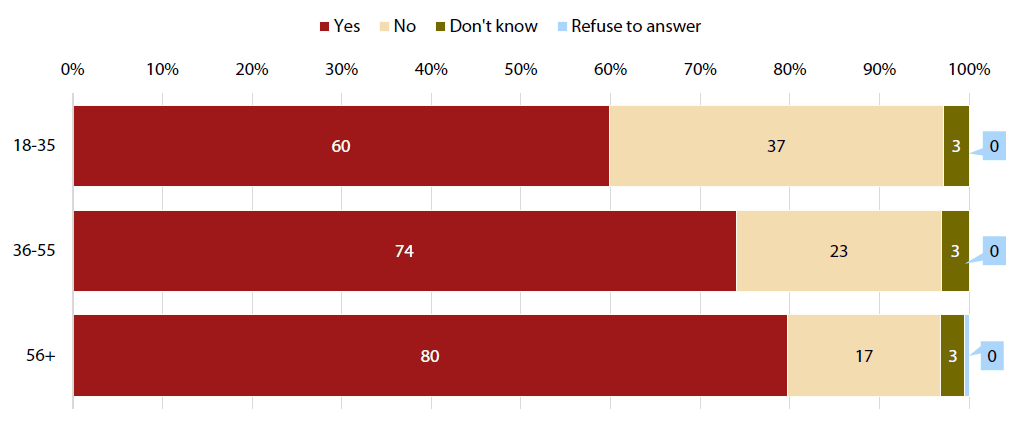

The institutional level provides yet another potential explanation of why young Georgians tend to avoid participating in elections. Georgian electoral law requires that voters cast their votes in the settlements where they are registered. However, because of internal migration, Georgians do not always dwell in the settlements where they are registered to vote9. As a result, young voters in Georgia report that they are not able to participate in the voting process, as they cannot travel to the settlement in which they are registered (See Figure 5 on p. 18). In addition to the existing electoral laws, the salience of electoral campaigns can also explain why there is a difference among age groups in regard to voting. As has already been mentioned, political campaigns in Georgia are usually concentrated on issues that correspond to the needs and requirements of an older generation10. According to the CRRC/NDI pre-electoral June 2017 survey, in comparison to other age groups, young Georgians have not given much thought to the upcoming local self-government elections, and even those young Georgians who plan to vote for a specific party are less confident in their choices (See Figure 8 and 9 on p. 21/22). Both Georgian politicians and voters are heavily dependent on television as a medium for communicating with the electorate and receiving information on political events (Anable 2006). According to the CRRC/NDI post-electoral November 2016 survey, the main source of information about parties and candidates was television, although its share was smaller in the 18–35 age group than it was in other generational groups11. The combination of these factors could eventually lead to increasingly indifferent attitudes among youth toward elections and politics.

The final element that may explain the low voter turnout among young people can be seen to be an individual-level factor. The CRRC/NDI pre-electoral June 2017 survey revealed that Georgian youth reported lower rates of voting in the previous local elections, while at the same time, they did not show much interest in the upcoming local self-governance elections (See Figure 6a–c on p. 18/20). Given these circumstances, it is not a surprise that young voters in Georgia are less informed about where people in their neighborhood go to vote (See Figure 6a–c on p. 18/20).

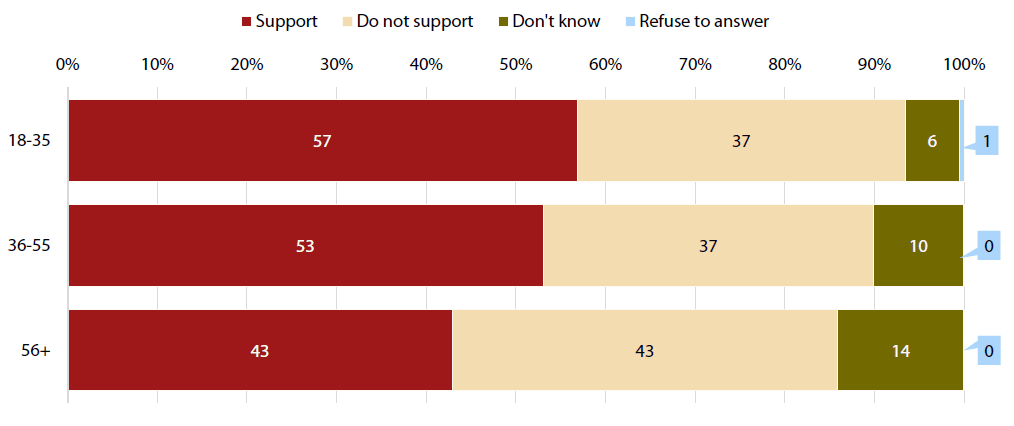

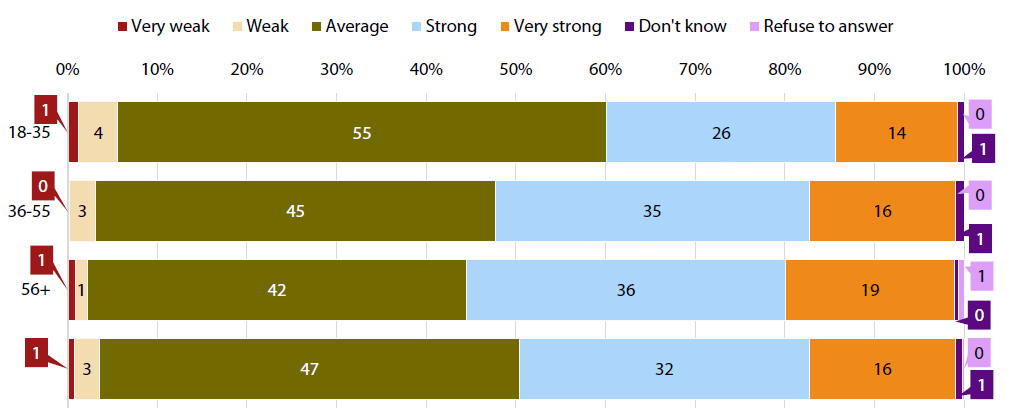

How to Encourage Young Voters?

Certain practical steps could help increase turnout in younger age groups. The first is associated with technological innovations, such as the introduction of absentee ballots or online voting. Significantly, the country does have the technical capacity to launch an online voting system, as the Minister of Justice of Georgia has already noted (Agenda.ge 2017). This could encourage more people to vote, and not just the young ones. As Figure 5 on p. 18 shows, voters under the age of 35 frequently reported that they were registered to vote in a different settlement than the one in which they lived and that they could not go to their precinct on Election Day. As Figures 7a and 7b on p. 21/22 show, young voters in Georgia are generally fond of innovations in electoral voting techniques, such as electronic and distance voting. However, past experience of electoral studies—for instance, the Estonian electoral reform—shows that the mere technical modification of an electoral system does not guarantee an increased turnout (Madise/Martens 2006).

Looking more at increased engagement and involvement of youth within the political process, literature on voting theory has shown that exposure to politically relevant issues increases the likelihood that youth will vote in elections (Kaid et.al 2007). Green and Gerber (2015) claim that “the more personal the interaction between campaign and potential voter, the more it raises a person’s chances of voting.” Therefore, direct engagement with young voters is vital in encouraging them to vote. The 2017 Tbilisi Mayoral elections have taken the first steps in mobilizing young activists around politicians12 and in attracting young voters with interesting topics such as supporting the “Night Life” of the capital13.

Conclusion

The detachment from political processes and the lack of knowledge about politics and specifically electoral processes is related to low turnout among young Georgian voters. In addition, institutional level constraints, such as living in a different electoral district, can also contribute to a lack of participation in elections. It is also important to note that the political system and political culture of Georgian parties also have an impact on youth frustration with elections. Therefore, in order to increase voter turnout among young Georgians, changes must be made both within electoral procedures and within political agendas.

Notes

1 The party, whose stated goal is to attract young educated voters, promotes socially liberal and fiscally conservative values. Source of the commercial: <https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=jHHbyv87z7U>

2 The 2016 parliamentary elections were held on October 8th, 2016, and the runoffs were held on October 30th, 2016.

3 Source: <http://cesko.ge/res/old/other/29/29081.pdf>

4 The Caucasus Research Resource Centers. (2016) “Caucasus Barometer”. Retrieved through ODA—<http://caucasusbarom eter.org/en/cb2012ge/VOTLELE/> on September 18th, 2017.

5 The variable was computed using following methods: respondents were given one point for each question they answered in a way consistent with voting, resulting in overall likelihood of voting scores ranging from 0 to 5. Numbers 0, 1, 2 and 3 from the Voter Model were grouped together and labeled as likely abstainers. For more information, please visit: <http://caucasus barometer.org/en/nj2017ge/VOTMODEL/>

6 The Caucasus Research Resource Centers. (2016) “Caucasus Barometer". Retrieved through ODA—<http://caucasusbar ometer.org/en/cb2015ge/DISCPOL-by-AGEGROUP/> on September 11th, 2017.

7 The Caucasus Research Resource Centers. (2016) “Caucasus Barometer". Retrieved through ODA—<http://caucasusbarom eter.org/en/nn2016ge/MAJNAME-by-AGEGROUP/> on September 11th, 2017.

8 The aim of the Commission is to elaborate the draft law on revision of the Constitution of Georgia. For more information, please visit: <http://constitution.parliament.ge/en-52>

9 The Caucasus Research Resource Centers. (2016) “Caucasus Barometer”. Retrieved through ODA—<http://caucasusbarom eter.org/en/na2014ge/LIVEREG-by-AGEGROUP/> on September 18th, 2017.

10 The project implemented by The Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy (NIMD) makes it possible to compare the policy programs of key political parties in Georgia. According to the programs, social assistance and pensions are top priorities for parties, and they pay little attention to the spending related to youth issues. Source: <http://nimd.ge/documents/NIMD_ wigni_ENG.pdf; http://partiebi.ge/new/>

11 The Caucasus Research Resource Centers. (2016) “Caucasus Barometer”. Retrieved through ODA—<http://caucasusbarom eter.org/en/nn2016ge/INFOSOURCE-by-AGEGROUP/> on September 11th, 2017.

12 The team of independent candidate and one of the major challenger for Tbilisi Mayor post consistent mostly from young activists. Source: <http://netgazeti.ge/news/208492/>

13 From the advertisement of governmental candidate for Tbilisi Mayor and former Vice-Premier, Kakha Kaladze. Source: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lF1oZIxCUXE>

Bibliography

Agenda.ge (2017) Georgia technically ready for electronic voting [online], 2017. Available from: <http://agenda.ge/ news/46019/eng> [Accessed September 4th 2017]

Anable, D., 2006. The Role of Georgia’s media—and Western aid—in the Rose Revolution. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 11(3), pp. 7–43.

Fieldhouse, E., Tranmer, M. and Russell, A., 2007. Something about young people or something about elections? Electoral participation of young people in Europe: Evidence from a multilevel analysis of the European Social Survey. European Journal of Political Research, 46(6), pp. 797–822.

Green, D.P. and Gerber, A.S., 2015. Get out the vote: How to increase voter turnout. Brookings Institution Press.

Economist 2014. Why young people don’t vote. [online], Available from: <https://www.economist.com/blogs/econ omist-explains/2014/10/economist-explains-24> [Accessed September 11th, 2017]

Esser, F. and De Vreese, C.H., 2007. Comparing young voters’ political engagement in the United States and Europe. American Behavioral Scientist, 50(9), pp. 1195–1213.

EUROPP 2013. Young people are less likely to vote than older citizens, but they are also more diverse in how they choose to participate in politics. [online], Available from: <http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2013/07/19/young-people-are-less-likely-to-vote-than-older-citizens-but-they-are-also-more-diverse-in-how-they-choose-to-participate-in-politics/> [Accessed September 11th, 2017]

Holbrook, A.L. and Krosnick, J.A., 2009. Social desirability bias in voter turnout reports: Tests using the item count technique. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(1), pp. 37–67.

Kaid, L.L., McKinney, M.S. and Tedesco, J.C., 2007. Introduction: Political information efficacy and young voters. American Behavioral Scientist 50 (2007).

Madise, Ü. and Martens, T., 2006. E-voting in Estonia 2005. The first practice of country-wide binding Internet voting in the world. Electronic voting, 86 (2006).

Norris, P., 2003. Young people & political activism: From the politics of loyalties to the politics of choice? Report for the Council of Europe Symposium: “Young people and democratic institutions: From disillusionment to participation,” November. Strasbourg, France.

About the Author

Rati Shubladze is a researcher at CRRC-Georgia. He holds a Master’s degree in Social Sciences from Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University (TSU) and is currently pursuing a Ph.D. from the Department of Sociology and Social Work at TSU. Rati’s doctoral research investigates electoral behavior in Georgia. He also teaches undergraduate and graduate level research methods classes at TSU.

Figure 1: Did You Vote in October 8 Parliamentary Elections/ the Runoffs on October 30? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, November 2016)

Figure 2a: If Parliamentary Elections Were Held Tomorrow, Would You Vote? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2016)

Figure 2b: If Local Self-Government Elections Were Held Tomorrow, Would You Vote? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2016)

Figure 3: Voter Model By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 4a: [Are You] Aware That Commission Adopted a Draft of Revision of the Constitution? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 4b: Do You Feel You Have Enough Information about the Constitutional Changes? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 5: What Was the Main Reason You Did Not Vote in the Parliamentary Elections? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, November 2016)

Figure 6a: Did You Vote in the Last Local Elections? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 6b: How Much Thought Have You Given to the Upcoming Local Self-Government Elections? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 6c: Do You Happen to Know Where People Who Live in Your Neighbourhood Go to Vote? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 7a: Would [You] Support Electronic Voting, People Voting Using Computer on Precinct? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2016)

Figure 7b: Would [You] Support Voting Using the Internet Without Going to the Electoral Precinct? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2016)

Figure 8: How Much Thought Have You Given to the Upcoming Local Self-Government Elections? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

Figure 9: How Would You Describe Your Support for Your First Choice? By Age Group (%) (CRRC/NDI survey, June 2017)

The Georgian Economy on a Stable Growth Path

By Ricardo Giucci and Anne Mdinaradze (German Economic Team Georgia)

Abstract

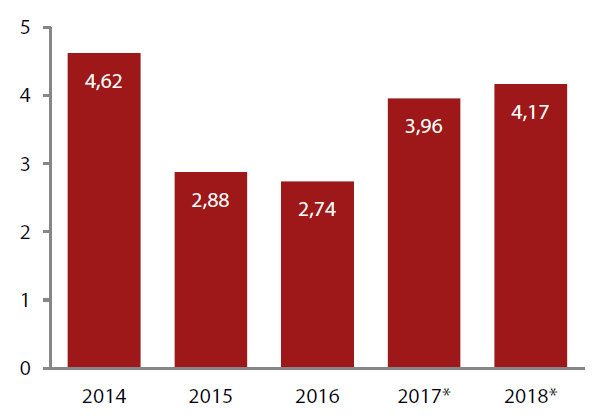

The Georgian economy is developing well: the GDP increased by 2.7% in 2016 and is expected to grow by 4.0% in 2017. With respect to demand, public investment is a key driver for growth this year. With respect to supply, construction and services remain the strongest contributors to growth.

A significant increase in excise taxes at the start of this year drove up consumer prices. As a result, inflation is expected to reach an average of 6.0% this year, which is higher than the inflation target of 4.0%. However, a significant inflation reduction is forecasted for next year.

Exports of goods are traditionally weak in Georgia, thus contributing to a large trade deficit. At the same time, it is important to emphasise that Georgia is a net exporter of services, especially in the tourism sector. The current account deficit will reach 13% of the GDP in 2017 and will continue to be financed by strong FDI inflows that amount to 11% of the GDP.

The budget deficit for this year is scheduled to amount to 3.7% of the GDP. A major shift from current to investment expenditures is foreseen, with positive long-term implications on economic growth.

GDP Growth Driven by Public Investment

Despite weak growth for regional trade partners, Georgia maintained a stable growth path during 2016 with its GDP increasing by 2.7%. This year, economic growth was originally forecasted to reach 3.5%. However, due to better than expected performance of the economy, the IMF forecast was revised to 4.0% for 2017 in the October World Economic Outlook. The main reason for this development on the demand side is due to stronger public investment. It remains to be seen whether the expectation that a higher public investment will be accompanied by a rise in private investment will be realised. Aside from these internal factors, economic growth is also supported by a recovering external sector. On the supply side, the construction and services sectors (in particular tourism) continue to be the growth drivers.

It is a positive achievement that the Georgian economy exhibited stable positive growth rates even under difficult external conditions in 2014–2016. The growth trend is expected to continue with the GDP increasing by almost 4.2% in 2018. In addition, the potential exists to achieve even higher growth rates. Furthermore, growth remains unbalanced due to an underdeveloped industrial sector and an agricultural sector that is small and stagnating.

Figure 1: Georgia: Real GDP Growth (% change year-over-year)

Excise Taxes Drive up Inflation in 2017

There were several reasons for low inflation in 2016. Due to weak aggregate demand, low oil prices and a high base effect from the previous year, prices had increased by only 2.1%. In 2017, however, inflation will increase significantly to an average of 6.0%. This comes after a strong increase of excise taxes for fuel, cars, tobacco and gas, which affect the price level. In response, the National Bank of Georgia (NBG) increased its policy rate from 6.5% to 7.0% in early 2017 in order to keep inflation in the target corridor. In 2018, the effect of increased excise taxes will weaken, and inflation is expected to meet its target of 3.0%.

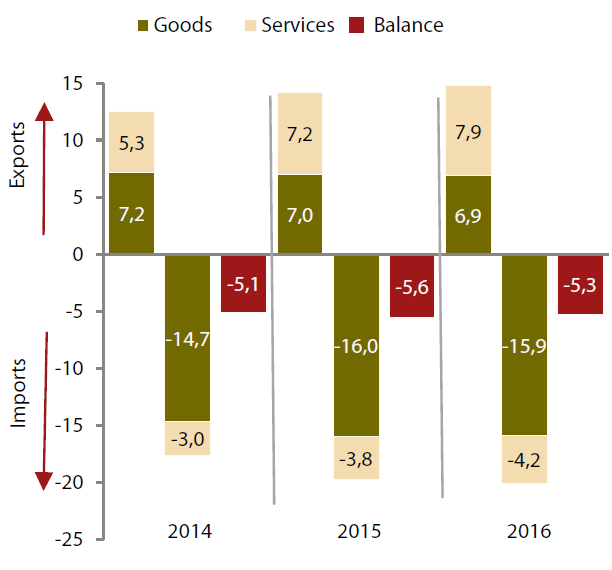

Persistently Large Trade Deficit

As in previous years, the Georgian trade balance continues to be negative, which is mainly due to weak export values. In 2016, imports remained almost unchanged and exports decreased by 4.2% due to low commodity prices. As Georgian exports are dominated by few commodities, they strongly reflect the development of world market prices.

However, a closer look at Georgian exports reveals an interesting picture. Exported goods account for only 47% of the country’s total exports. The remaining 53% are made up by services. In fact, Georgia is a net exporter of services. In 2016, exports of services increased by 10% and imports increased by 11%. Transportation and tourism are the sectors which contribute most to the positive services balance. The revenues generated by the tourism sector exceed total goods exports.

Figure 2: Georgia: Trade in Goods and Services (Gel bn)

Current Account and Exchange Rate

The structural weakness of goods exports is the main reason for the persistently negative current account balance. The IMF forecasts the country’s current account deficit to reach almost 12% of the GDP in 2017. This is not expected to change significantly in 2018. To date, strong FDI inflows accounting for 11% of the GDP provide stable financing of the current account deficit. However, the persistent current account deficit remains a source of risk.

The NBG’s flexible exchange rate policy allows for rapid economic absorption of external shocks. In 2014– 2016, the exchange rate reacted to strong fluctuations of the main trading partners’ exchange rates. In the recent past, the NBG intervened by buying US dollars to increase the country’s international reserves as stipulated in the IMF programme.

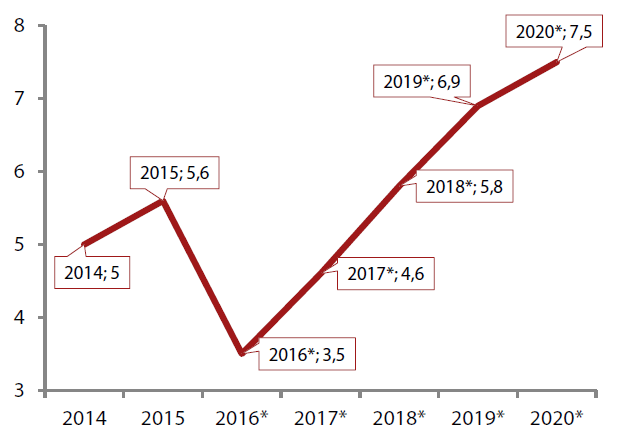

Growth-Oriented Budget in 2017

In the context of parliamentary elections in 2016, when corporate tax reform was discussed and increased public investment was announced, it was feared that the budget deficit might increase to 5% of the GDP in 2017. However, after elections, the ruling party took measures to counterbalance the budget. In particular, excise taxes were increased significantly, and the budget deficit is planned at “only” 3.7% of the GDP in 2017. The new IMF programme stipulates the continuation of the consolidation process. The budget deficit is to be reduced to 2.8% by 2020.

As it was announced during the election campaign, public investment is planned to strongly increase from 6.5% of the GDP in 2016 to 7.5% in 2020. This implies an immense budgetary reallocation from current to investment expenditures, with a positive long-term impact on economic growth.

Figure 3: Georgia: Public Investment (% of GDP)

Conclusions and Outlook

The Georgian economy is on a stable growth path. The reallocation of government expenditures from consumption to investment is, in our view, a very positive step with long-term implications for the future of the country. The IMF programme provides a good economic policy framework for stability in the coming years.

At the same time, policy measures should be taken to reduce the dependency on services and secure a more balanced approach to economic growth. The current focus on services should be complemented with measures to promote agriculture and industry. In such a way, the strong exposure to global commodity prices and the large trade deficit could be reduced, thus keeping macroeconomic risks at bay.

About the Authors

Dr Ricardo Giucci is the team leader and Anne Mdinaradze is an analyst at the German Economic Team (GET) Georgia. GET Georgia advises the Government of Georgia on economic policy issues. It is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.