Russian Analytical Digest No 225: Russia´s Pension Reform

8 Oct 2018

By Martin Brand, Elena Maltseva and Irina Meyer (Olimpieva) for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article featured here was originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 8 October 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Kremlin.ru external page(CC BY 4.0)call_made

Carrot and Stick: How It Was Possible to Raise the Retirement Age in Russia

By Martin Brand, Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen

Abstract

At the end of September, the Russian Parliament passed a law increasing the retirement age by five years to 60 for women and 65 for men. The aim was to move toward sustainable finances for the Russian Pension Fund, but the move proved extremely unpopular. In the light of considerable protests against the reform announced in June—just hours before the opening of the World Cup—the government was forced to react to popular discontent with a public debate and concessions.

In the Shadow of the World Cup

This summer, the Russian government faced a dilemma that was difficult to resolve: For years, the Russian Pension Fund (PFR) has been in deficit as the pension contributions fall far short of covering current expenditures on old-age pensions. Therefore, when public attention was focused on the World Cup and public protests were restricted for security reasons, Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev announced a painful solution to the problem: Women should work eight years longer, men five.

However, the project has led to public discontent for at least three crucial reasons: First, pension reform threatens the social security of people aged 55–65. Second, due to corruption and nepotism, the political elite seems to lack the legitimacy to carry out reforms that deeply affect people’s lives.. Third, the current pension age of 55 years for women and 60 for men has enormous symbolic significance. For many people in Russia it seems to be a kind of last bastion for the defence of social achievements from Soviet times.

Accordingly, there was broad public opposition to the government’s plan to raise the retirement age—ranging from the systemic opposition parties in the Duma (in this case all parties except United Russia) to the trade unions and the movement of Alexei Navalny. Regular demonstrations have taken place throughout the country since July. In polls and elections, approval for both Vladimir Putin and United Russia fell after the reform plans were announced.

The crucial question in early fall 2018 was therefore: Will the government of Prime Minister Medvedev find a way to pass the reform?

Key Problems of the Russian Pension System

In order to understand the rationale behind the planned increase in the retirement age, it is worth first taking a look at the three central problems in how Russia provides for its senior citizens: 1) the deficit in the pension fund, 2) demographic development and 3) low pension benefits.

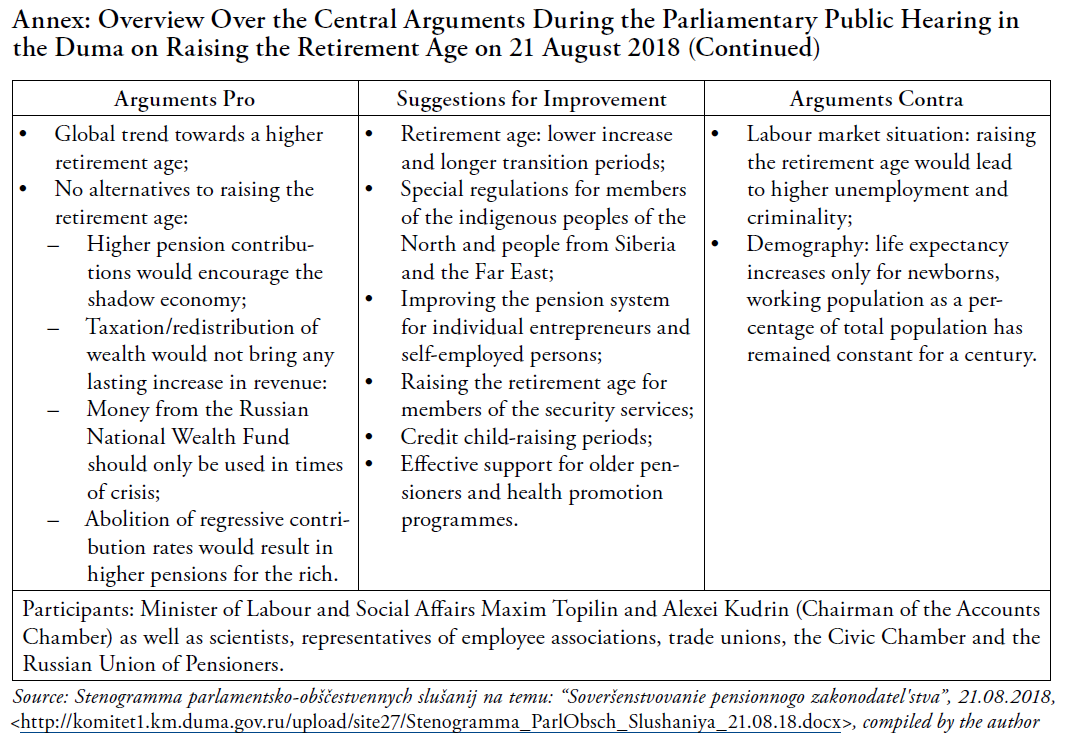

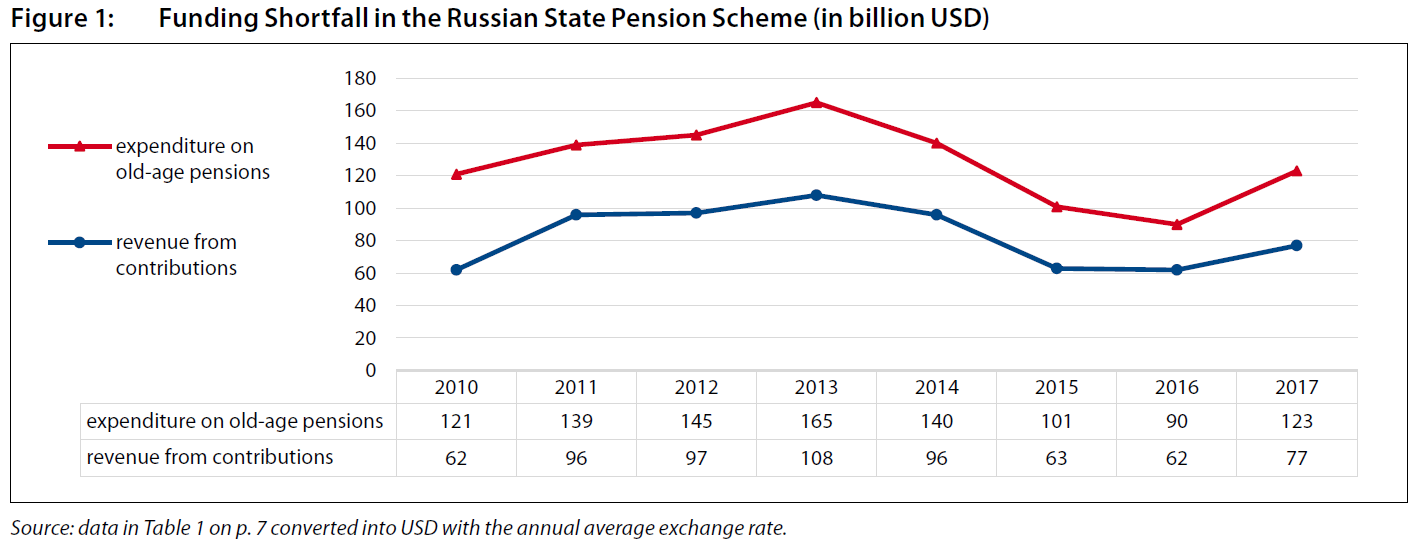

The core economic problem of the pension system is the deficit of the Pension Fund. It amounts to about one third of pension expenditure and must be covered year after year by subsidies from the federal state budget (see Table 1 on p. 7). The shortfall is problematic for two reasons: On the one hand, financing from the federal budget contradicts the principle of a contributory pension system in which current old-age pensions are paid out of current employees’ pension contributions (In Russia, employers cover all of the pension contributions and employees do not contribute directly). On the other hand—and this is the really serious problem—the subsidies place a considerable burden on the federal state budget. Slightly more than one fifth of total federal government expenditures flow into the Pension Fund (see Table 1 on p. 7). At a time when Russia’s economic development is stagnating (due to the low oil price, Western sanctions and structural problems) and the pressure to consolidate the state budget is growing, these subsidies to the Pension Fund are a prime target for austerity efforts.

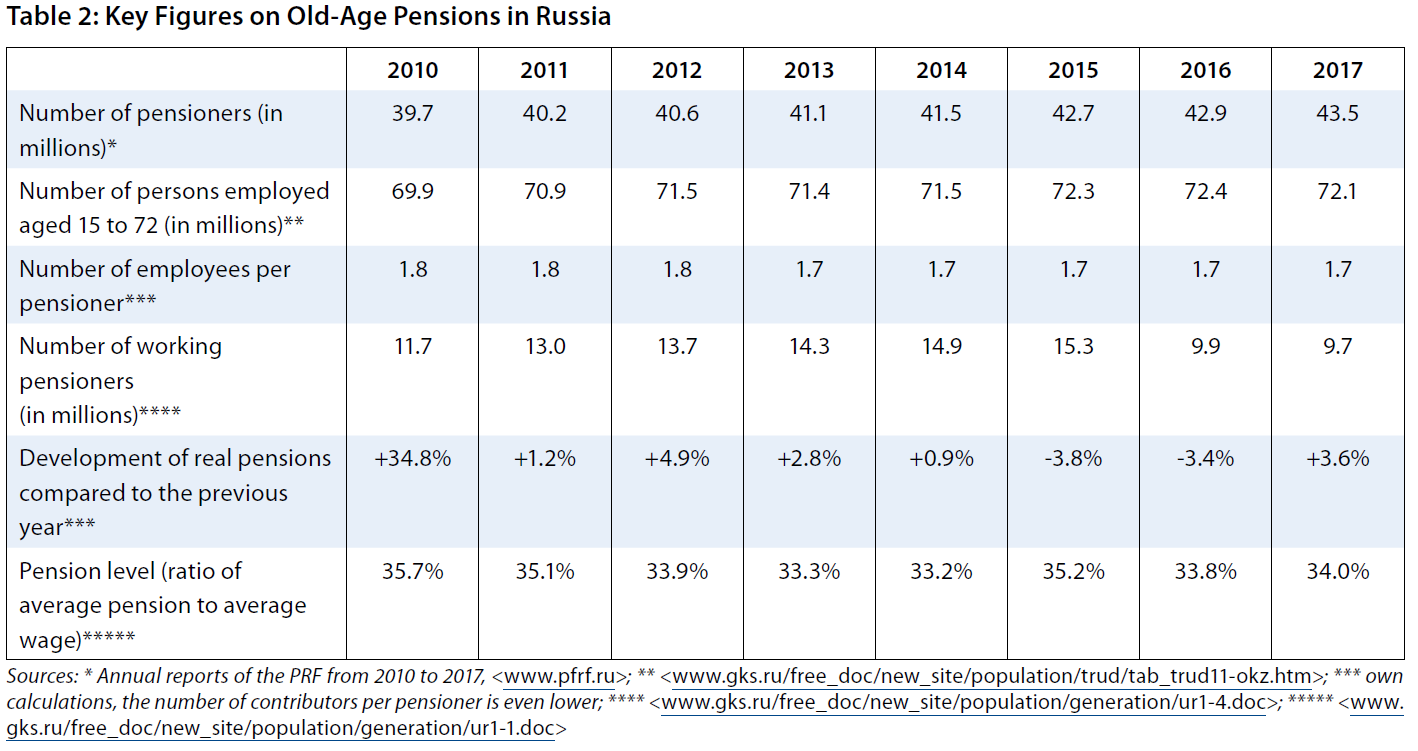

Another problem of old-age provision in Russia is the demographic situation. Russia’s society is ageing—and according to the UN World Population Prospect, this trend will continue in the coming decades, even if the birth rate has risen significantly in recent years thanks to financial incentives for families. Since 2010, the number of pensioners has risen by almost four million, while the number of people employed has stagnated for three years. There are only 1.7 employed people per pension recipient. Almost one third (30%) of all people in Russia receive an old-age pension (see Table 2 on p. 7). Although the trend towards ageing societies is putting pressure on pension systems worldwide, compared with many OECD countries, the ratio of employed people to pensioners in Russia is low.

Compounding these issues, the third fundamental problem is the relatively low level of the pensions. The pension level for an average earner is currently around one third (34%) of the former wage. This figure, too, is low compared to many OECD countries. That’s why almost one in four pensioners in Russia continues to work, especially in the early years of retirement (see Table 2 on p. 7). Accordingly, for younger pensioners, in particular, the old-age pension often serves as a kind of basic income that must be topped up through gainful employment. Inactive pensioners, on the other hand, are particularly at risk of poverty.

Pension Reforms of the Past

These core structural problems of pension provision in Russia have existed for a long time. Over the past 20 years, they have led to numerous reforms aimed at stabilising the pension system in the long term:

- In 1990 the Pension Fund of the Russian Federation was established as the administrative body of the contributory pay-as-you- go pension system;

- In 2002, the pay-as-you-go pension system was extended to include a compulsory and a state-supported voluntary funded pension scheme;

- Since 2014, funded pension schemes have been suspended in order to use the contributions to finance the pay-as-you-go pension (now extended to 2020);

- In 2015, a new pension formula was introduced that takes into account years of working life employment, wage level and real retirement age, and the early retirement system for various occupational groups was reformed;

- In 2017, the retirement age for civil service employees was raised to 63/65 (women/men).

However, the general retirement age of 55/60 (women/ men) years remained unchanged. Although experts from international organisations and Russian economists and pension experts repeatedly recommended raising the general retirement age, this was long considered a taboo political issue. President Putin declared in 2005 that the retirement age would not be raised as long as he was president.

Raising the Retirement Age: A First Bill

The retirement age of 55/60 (women/men) years inherited from the Soviet Union is one of the lowest in the world. It is therefore not surprising that, since their independence, almost all post-Soviet states except Uzbekistan have raised the retirement age—most recently Belarus and Ukraine in 2017. In June 2018, the Russian government under Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev broke the taboo and announced, with reference to international developments, that it would raise the retirement age in Russia. The aim, it said, was to create a sustainable financing basis for old-age provision and to increase pension payments. The first draft law contained the following detailed provisions:

- From 2019, the general retirement age should be gradually increased: to 65 for men by 2023 and to 63 for women by 2026;

- By analogy, the social pension should also be increased from 60/65 to 65/70 (women/men) years. Social pensions are paid to people who, for whatever reason, are not entitled to an insurance pension;

- Some special arrangements to allow early retirement for certain categories of people should also be increased by 8/5 (women/men) years, e.g. for relatives of deceased soldiers or indigenous peoples living in the North;

- Teachers, healthcare workers and artists have the right to early retirement after a certain number of years of service. This right is to remain, but is to be postponed, gradually to eight years. For other groups of people with the right to early retirement, e.g. from security structures, there will be no change.

This bill was adopted on 19 July after its first reading with the votes of the United Russia (UR) parliamentary group (only one member of UR voted against). The members of all other parliamentary groups present (KPRF, LDPR and A Just Russia) voted unanimously against.

Protests

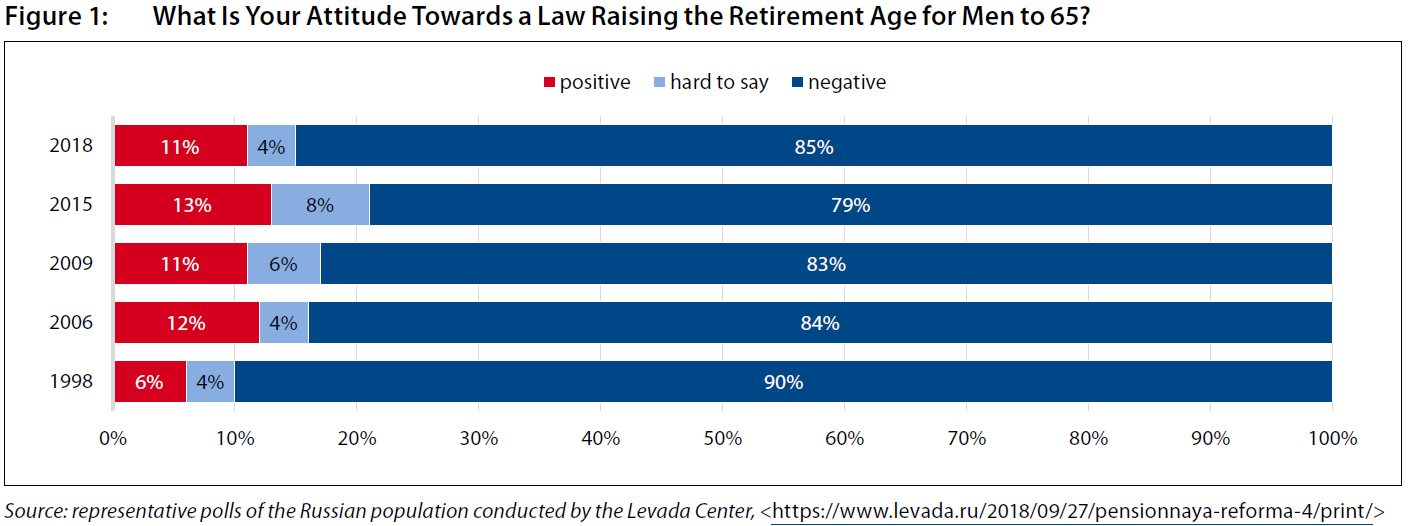

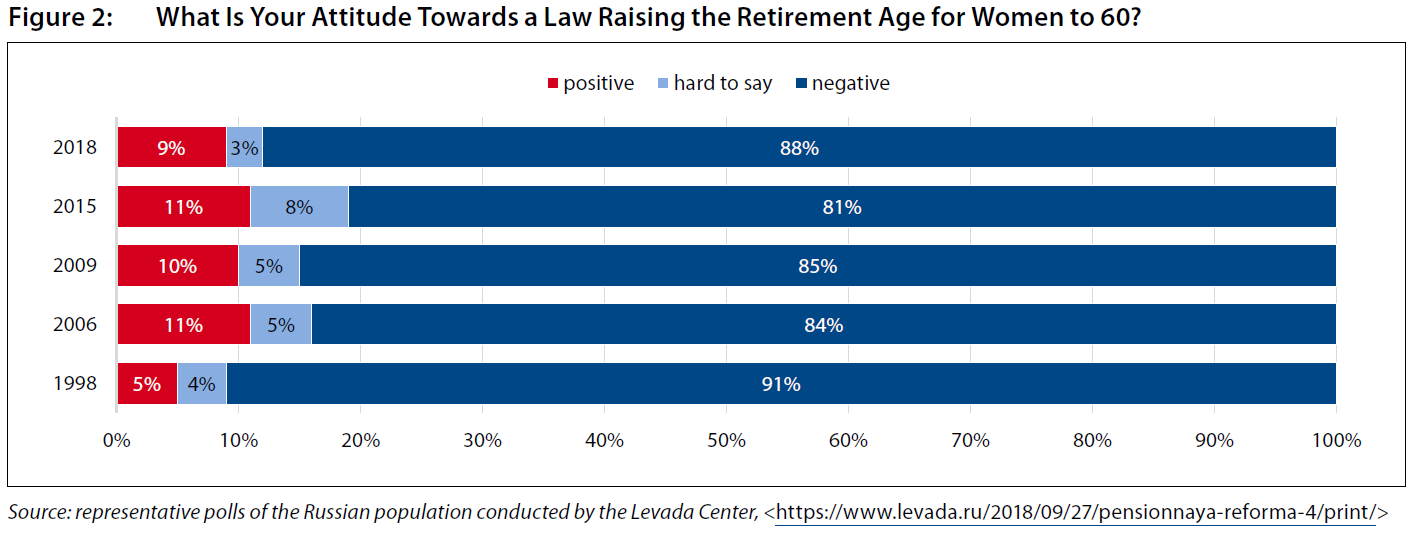

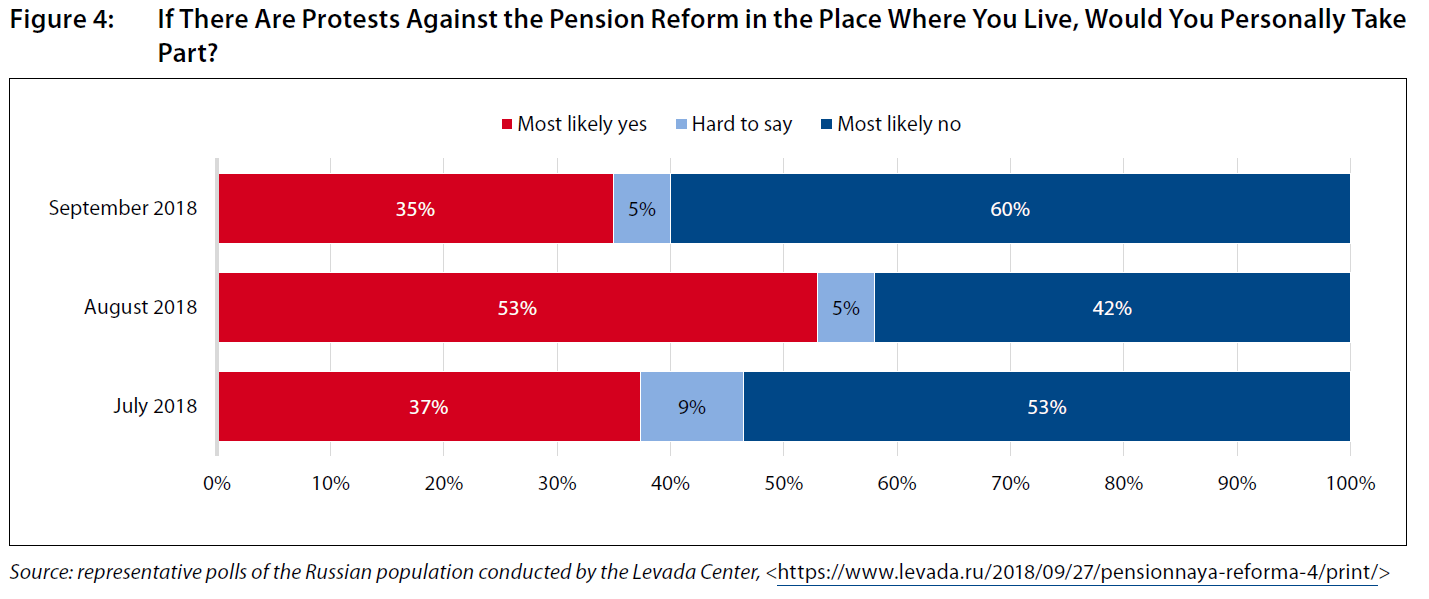

This Duma voting reflects the widespread unpopularity of the pension reform plan among the population. Surveys by opinion research institutes Levada and FOM show clearly: The vast majority of the population (between 80 and 90 percent) strongly oppose a higher retirement age. Within a few days after the Prime Minister announced the reform plan, the approval ratings for Dmitry Medvedev, Vladimir Putin, the Russian government and the party United Russia dropped by 10 to 15 percent. What’s more, the political protest potential also rose sharply. In a survey conducted by the Levada Center, more than a third of the population said that they were ready to take part in rallies against the pension reform if such demonstrations were to take place in their city.

However, resistance to the pension reform is not only manifested in surveys. Almost three million people signed an online petition by the independent trade union centre “Confederation of Labour of Russia” (KTR) against raising the retirement age. In many Russian cities, people took to the streets. Several hundred to several thousand demonstrators took part in each of the 100 plus demonstrations nationwide. Ultimately, it was not so much the number of demonstrations and participants that attracted attention, but the broad spectrum of organisers. Rally leaders included representatives of the left-wing (including KPRF, A Just Russia, Left Front), liberal (including Yabloko, PARNAS) and right-wing (LDPR) parties and organizations as well as trade unions (KTR, the official FNPR) and the opposition movement of Alexei Navalny.

The authorities were accordingly nervous: some demonstrations were banned and there were repeated reports that protesters were arrested. In August, Sergei Udaltsov, coordinator of the Left Front and one of the leaders during the 2012 protests against Vladimir Putin, as well as Alexei Navalny were each sentenced to 30 days imprisonment. Thus two important figures of the extra-parliamentary opposition were temporarily withdrawn from circulation.

Nevertheless, Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) was able to publish two videos in which the Pension Fund and its head Anton Drozdov were accused of embezzlement. Drozdov—a long-time state official, who never worked in the free economy—is said to have real estate worth several million US dollars. Based on these accusations, Navalny’s movement called for nationwide protests against the pension reform on 9 September—the day of regional and local elections in Russia. Security authorities responded to these protests with violence and, according to information from OVD-Info, arrested 1,195 people, mainly in St. Petersburg.

Finally, the protests against the pension reform were reflected in the results of regional and local elections. The nationwide dominant pro-Kremlin party of power United Russia lost considerable support among voters. In three regional parliaments, the KPRF became the strongest party ahead of United Russia—a political earthquake by Russian standards. Since 2007, according to Arkadiy Lyubarev from the voters’ rights movement Golos, United Russia has always won the majority in all parliamentary elections in the regions. Moreover, contrary to expectations, the United Russia candidate was not able to win first round gubernatorial elections in four regions. Finally, two LDPR candidates won the run-off, one election was declared invalid after massive falsifications in favour of the United Russia candidate and another was postponed after the United Russia candidate’s withdrawal.

Political Ways of Conflict Resolution

- Faced with protests and resistance, the regime felt compelled to initiate a political process in order to enclose the emerging conflict in society. This process consisted of three elements:

- A parliamentary public hearing in the Duma on improving the pension legislation on 21 August 2018;

- A television address by Vladimir Putin on 29 August 2018;

- Adoption of the law in second and third reading with inclusion of numerous amendments on 26/27 September 2018.

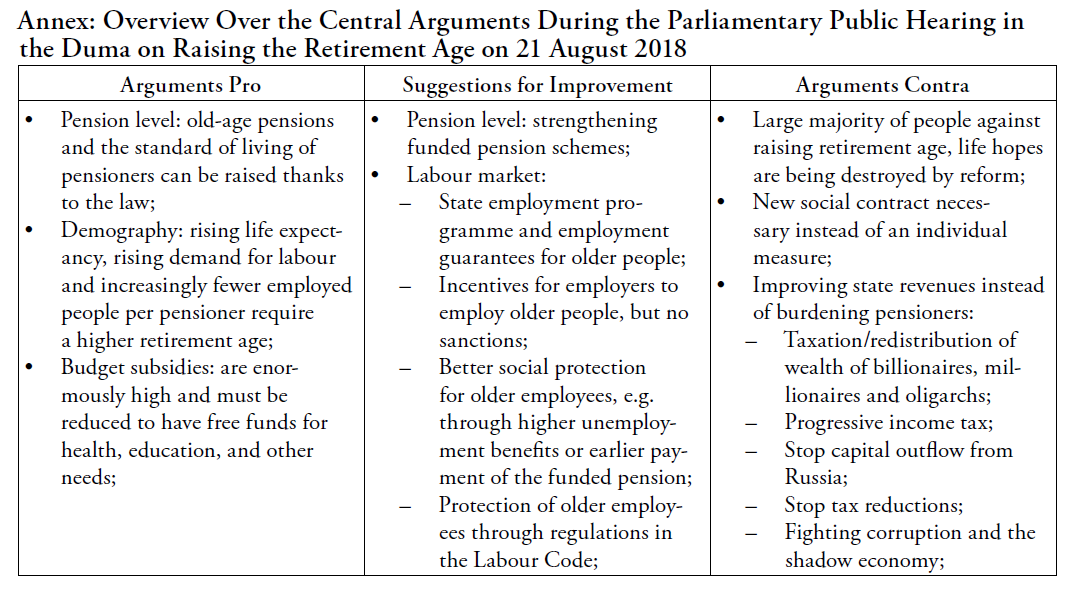

The aim of the public parliamentary hearing in the Duma was to imitate a public debate. Yet the framework of this discussion had already been defined by the Medvedev government’s draft law. So the hearing was all about justifying the need for a higher retirement age and to articulate proposals for changes on details. Only the leaders of the three opposition parliamentary groups (KPRF, LDPR and A Just Russia) and the representative of the Confederation of Labour of Russia voiced fundamental criticism of the retirement age increase (see the overview given in the appendix). Nevertheless, the debate served an important purpose: A range of stakeholders were able to express the concerns of their clientele and argue for improvements. Thus, the debate served as a platform for the public to respond to the government’s reform plan—but not as platform for competing political ideas.

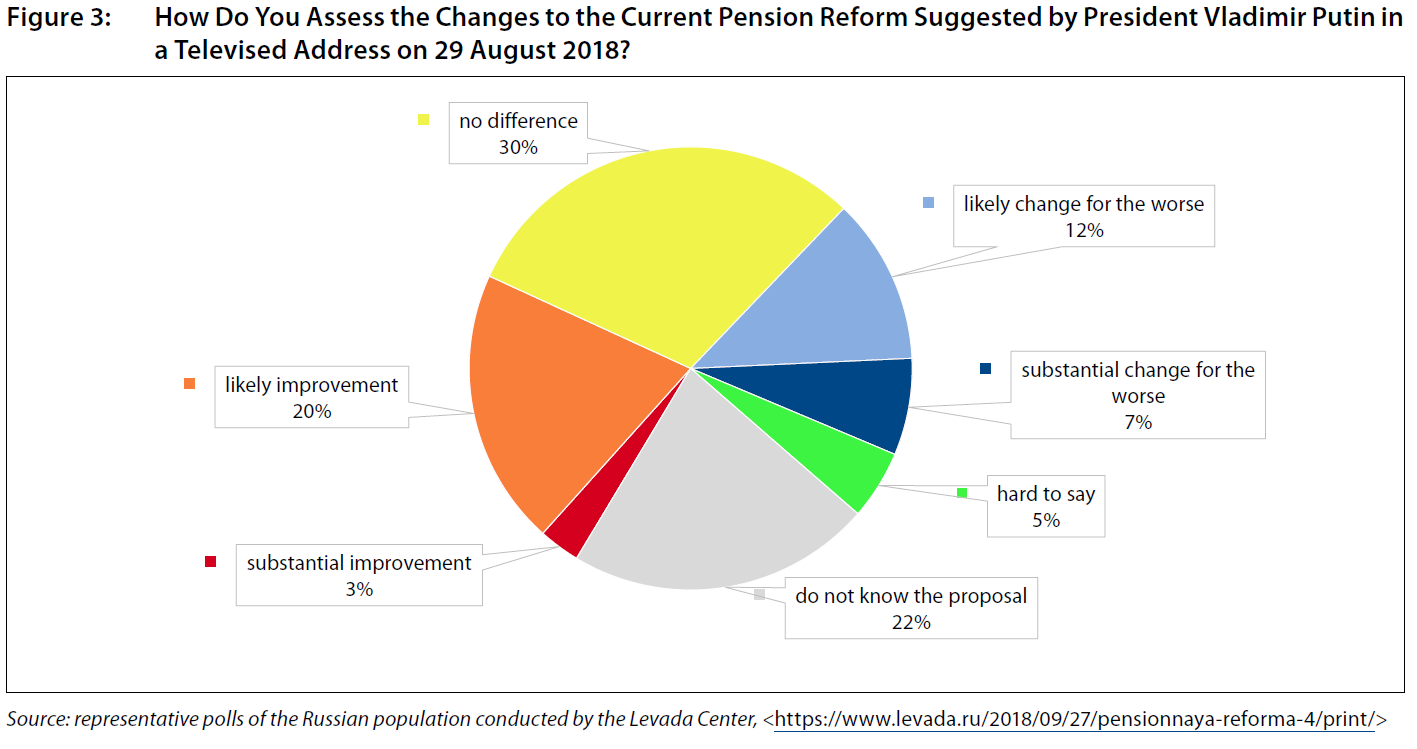

Finally, President Putin intervened personally in the debate and explained by televised address why a higher retirement age was necessary. At the same time, he formulated changes to the draft law in order to soften its social consequences as far as possible:

- Retirement age: women should receive state pension from the age of 60, women with three or more children should have the right to retire earlier, the necessary length of employment for early retirement should be reduced by three years to 37/42 (women/ men) years;

- Labour market situation: ban on dismissals five years before retirement age, doubling unemployment benefits and training for older workers;

- Privileges and supplements: maintain existing benefits for pensioners from 55/60 years of age (women/ men), pension supplements for the rural population, maintenance of special arrangements for early retirement of certain categories of people.

This ping-pong game with suggestions from the government, which are publicly weakened by the president, was widely expected. Putin’s proposed changes failed, however, to prevent nationwide demonstrations on 9 September and the decline of United Russia’s popularity in many regions. Less than a third (29%) of the Russians believe that Putin’s proposals actually improved the pension reform that had been announced earlier in the summer.

Finally, the pension reform was passed on 26/27 September in its second and third readings in parliament. Putin’s proposed changes were adopted unanimously (even the opposition voted in favour), then the law to raise the retirement age was passed with the votes of United Russia and against the votes of the opposition. The increase in the retirement age is flanked by a number of other laws that react on some key arguments by opponents:

- Ratification of the ILO Convention concerning Minimum Standards of Social Security, which demands a minimum pension level of 40%;

- Extension of the Russian Criminal Code to include a paragraph protecting older workers against dismissal on grounds of age;

- Extension of the Russian Budget Code to include a paragraph which states that seized funds from corruption cases must flow into the Pension Fund.

Conclusion

Within a little over 100 days, Russia has implemented a pension reform that had been taboo for many years: the retirement age was increased by five years to 60 for women and 65 for men. But although there were rational reasons for doing so, the overwhelming majority of people in Russia opposed the reform. That the changes could nevertheless be implemented within a short time is a vivid example of how the technology of governance in Russia works.

First, a strategically opportune time was chosen to announce the raising of the retirement age. In June many people in Russia turned their attention to the World Cup and at the same time the right to hold demonstrations in the host-cities was restricted. Then a strategy of repressions and concessions followed in response to the burgeoning protests: demonstration bans, arrests, violence and electoral fraud, on the one hand, and a guided debate that led to expected compromises, on the other.

Was this carrot (a relatively small one) and stick approach successful? Most likely. The reform passed and although a broad majority still rejects raising the retirement age, the protest potential has clearly decreased in September. What remains, however, are fears of social decline and poverty, especially among those directly affected by the pension reform, and considerable distrust in the political elite, who are widely perceived as corrupt. But these problems seem to be calculable for the political regime.

About the Author

Martin Brand is research fellow at the CRC 1342 “Global Dynamics of Social Policy,” Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen, where he is working on poverty policy in the post-Soviet era.

Annex

Statistics

Pensions in Russia

Opinion Poll

From Stagnation to Recalibration: The Three Stages in the Transformation of the Russian Pension System

By Elena Maltseva, University of Windsor

Abstract

The transformation of the Russian pension system went through three distinct stages—a decade-long period of policy inertia during the 1990s, rapid policy change during the early 2000s, and policy recalibration during the mid-2010s. The most significant reform—launched in 2002—transformed the Soviet pay-as-you-go (PAYG) pension system to a mixed system with a mandatory funded component. However, as time passed, the Russian government determined that the 2002 reform failed to deliver the desired results. This forced the government to make several adjustments to the Russian pension system that became particularly important in light of mounting demographic, economic and financial risks. The recalibration continued into 2018, when the government announced its decision to raise the retirement age. Despite such apparent instability, one element remained constant: since the early 1990s the transformation of the Russian pension system has been primarily driven by neoliberal economic advisers to the Russian government. And given the current geopolitical and economic risks that complicate the future of the Russian economy, this trend arguably is set to continue.

Much Talk, Little Action: Pension Reform under Yeltsin

Following the collapse of the USSR, the Russian Federation inherited the Soviet pay-as-you-go (PAYG) pension system, which guaranteed nearly universal pension coverage to all Soviet citizens (de Castello Branco, 1998; Buckley and Donahue, 2000). The system was characterized by low retirement age—60 for men and 55 for women, relatively high average replacement rates, and several additional benefits that were granted to selected population groups. This system came under pressure even before the collapse of the USSR, and the situation further worsened during the 1990s (de Castello Branco, 1998; see also Seitenova and Becker, 2004). The economic collapse, which accompanied the transition, contributed to a sharp increase in official unemployment rates, as well as informal and partial employment, thus affecting the number of formal sector workers whose contributions ensured the financial stability of the distributive pension system (de Castello Branco, 1998).

Responding to these challenges amid economic crisis and a worsening demographic situation, the government entrusted a team of young liberal economists led by Yegor Gaidar to craft economic and social reforms (Åslund, 1995). The Russian policy-makers were supported by international policy actors such as the World Bank (WB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which promoted a liberal policy paradigm as the only viable solution to all social problems, including the issue of old-age social security. The key elements of Gaidar’s economic program were price and trade liberalization accompanied by decreased state spending and tight control over the monetary supply, massive privatization, and radical retrenchment and liberalization of the Soviet welfare system (Cook, 2007).

However, despite the intention of a liberally-minded government to launch the welfare reforms, as well as the tremendous pressure from the IMF and the World Bank to implement the liberal Washington Consensus policies and the growing dependence on Western funds, institutional legacies, which manifested themselves in the form of electoral expectations and veto players defending the old order, prevented substantive reforms. In the end, external shocks, the Soviet legacies, and political considerations trumped the financial incentives and weakened the power of liberal entrepreneurs inside the government circles. As a result, even though the operation of the Soviet PAYG pension system displayed several shortcomings, the standoff between the seemingly incompatible liberal and left-wing political forces resulted in no more than parametric changes.

Liberal Reform in an Illiberal Context: Pension Reform under Putin

The paradigmatic breakthrough happened shortly after Vladimir Putin’s ascendance to power in 2000. The recentralization of Russia’s political institutions was accompanied by the arrival of young liberal reformers, who, akin to the Gaidar’s team from the early 1990s, declared their intention to reshape the social institutions in order to boost the country’s economic performance (Bohlen, 2000). According to German Gref, who was appointed the Minister of Economic Development and Trade in May 2000, the goal of the new government would be to modernize the Russian economy and make it “manageable and market-oriented”. In this context, the social security reform was needed to address Russia’s “demographic hole” problem, characterized by an increase in the number of pensioners and a reduction in the number of full-time workers contributing to the pension system (“Gref: Rossiia popadet v ‘demograficheskuiu iamu’”, 2000).

Several factors, including the benevolent international environment, which was largely supportive of Putin’s liberal economic and social reforms, a steady improvement in Russia’s economic situation, the centralization of Russia’s political institutions, and the tremendous “power over ideas” wielded by Vladimir Putin’s cabinet allowed the government to carry out the liberal economic and social reforms, which had been stagnating since the 1990s (“What Russia wants”, 2002; Carstensen and Schmidt, 2015; Kivinen and Cox, 2016; Bindman, 2017).

Launched in 2002, the Russian pension reform largely followed the World Bank pension model, as it transformed the Soviet PAYG system to a multi-pillar system that was comprised of three parts: (1) the basic pension, which was guaranteed by the state and offered to all categories of pension recipients regardless of their history of employment; (2) the mandatory pension insurance that had both a PAYG (unfunded) defined contribution component and a funded, but largely government managed, defined contribution component; and (3) the voluntary, supplementary pension (Afanasiev, 2003; Williamson et al., 2006). According to the original plan, once a year workers had an opportunity to decide whether to keep their savings in the Russian Pension Fund (PFR), which invested in secure government bonds, or transfer them to a non-state pension fund or a private management company, which promised greater opportunities and higher returns on investment (“Pensionnaia reforma 2002 goda”).

The reform marked an ultimate departure from the Soviet pay-as-you-go pension system to a system that was based on the logic of shared responsibility, in which the principal decisions about individual social security rested with the future pension recipient, and not the state. In that sense, the reform produced an important structural shift in the underlying principles of the Russian pension system, falling in line with the principles of neoliberal ideology. Seen from the economic perspective, the government hoped that the introduction of a funded pension pillar would stimulate investment in capital markets, contribute to long-term economic recovery, improve the management of the country’s financial resources, and increase the sustainability and transparency of the Russian pension system (Becker et al., 2009; see also Williamson et al., 2006; Orenstein, 2008; Sokhey, 2015).

However, a decade later, it became evident that the 2002 pension reform failed to achieve the desired results. Several factors, including continuously emerging external economic shocks, accompanied by the growing deficit in the Russian Pension Fund and the poor performance of the private funds, higher than expected transition costs, weak administrative and financial structures on which the reform rested, and the failure of the liberal pension ideas to “stick” with Russian values and expectations undermined the implementation of the reform and lowered the level of public trust in the sustainability and attractiveness of the new pension system.

In Search of a New Pension Arrangement: Russia’s Pension Reform at a Crossroads

By 2012, the realization was growing among the Russian government that if Russia wanted to continue its modernization course under the conditions of growing economic and international uncertainty, stable and sufficient financial injections into the economy were required. Therefore, another adjustment of the Russian pension system was in order. Two main options were on the table. Whereas advocates of a social approach were calling for making the mandatory savings accounts voluntary, the liberal camp and business sector advocated the elimination of the notional defined contribution accounts and argued that only a switch to a mandatory all-private savings system could save Russia’s pension system and by extension the capital market (Kulikov, 2011; Remington, 2015). Some liberal experts, such as the former finance minister Aleksei Kudrin, proposed increasing the retirement age gradually up to 70 years (Remington, 2015).

The debate ended with the president signing a compromise version of the pension reform, which introduced a new points-based pension formula and partially reversed the pension privatization by making the funded component optional. At the same time, it encouraged the workers to keep the funded component of their pensions with the help of a co-financing mechanism (“Sofinansirovanie pensii”, n.d.). However, the implementation of the 2013 pension reform was offset by the unfavourable economic situation, which continued into 2014 as a result of the crisis over Ukraine and declining oil prices (Remington, 2015). As a consequence, the Russian government faced severe strain in securing long-term investment capital for the national infrastructure projects it considered necessary to boost economic growth (Remington, 2015). In addition, if prior to the 2014 crisis the government was able to cover the deficits in the State Pension Fund through transfers from the federal budget, after the onset of the most recent economic crisis, the budget transfers dried up and the situation demanded the implementation of structural reforms (Cook and Aasland, 2016).

As fiscal stresses escalated, the government found itself in a difficult situation with a limited number of policy options: restoring the mandatory private pension component, raising social taxes, cutting spending, increasing the pension age, or cutting pension benefits (Remington, 2015). Faced with this challenge, the government decided to restore the mandatory private pension system and stated that these funds could be used for long-term capital investment in the economy, calling on the private pension funds to contribute to state infrastructure projects (Remington, 2015; Liutova, 2015).

In addition, the government returned to the question of increasing the pension age. The first step was made in 2015, when the government submitted a law to the parliament that presupposed a gradual increase of the retirement age for state officials to 65 from 60, which included civil servants, municipal employees and those in state positions (“Russia introduces law to raise retirement age for state officials to 65”, 2015). The bill signed into law by President Vladimir Putin in 2016 took effect from January 1, 2017. Furthermore, in 2016, the Center for Strategic Research, led by the ex-Finance Minister Alexey Kudrin, prepared for President Vladimir Putin a strategy, which proposed to reduce the number of pensioners by increasing the retirement age for women to 63 years and for men to 65 (“MVF porekomendoval Rossii”, 2017).

After the 2018 presidential election, the government announced its decision to raise the retirement age for men from 60 to 65 by 2028 and from 55 to 63 for women by 2034, but promised to keep some benefits and the early retirement option for selected population groups, such as the people working in harsh climatic conditions of the Far North. The reform was supported by the IMF (IMF, 2017). Following the protests, the president announced a softening of the proposed changes to the retirement age for women, which would be raised to 60 instead of 63, while the increase for men would remain the same. The reform is expected to start in 2019. In addition, the government indicated that it planned to move ahead with other policy innovations, such as abandoning the points system used to calculate one’s pension (“Bally s vozu, pensionnoi sisteme legche”, 2018).

In conclusion, as evident from this brief overview, the transformation of the Russian pension systems went through three major stages. During the 1990s, the liberal policy ideas, promoted by the Western policy advisors were very popular across the region, although their realization depended on the presence of strong policy actors capable of overcoming the various institutional and political obstacles to the reforms. In the case at hand, weak state capacity, coupled with institutional legacies in the form of electoral expectations and veto players defending the old order, prevented substantive reforms. The reform was launched following the arrival of new political actors, who proved to be capable of navigating and changing the complex political and institutional environment, which in the end facilitated the historic policy breakthrough. Despite the successful start, the 2002 pension reform failed to become institutionalized because of a combination of endogenous and exogenous factors, including the onset of a global financial and political crisis (an unexpected external shock), and institutional bottlenecks that constrained the actions of the key policy actors responsible for the implementation of the reform, weakened reform legitimation in the eyes of the public, and the actual deficiencies in the program of the new pension system.

The subsequent recalibration attempts that followed in 2013, 2015 and 2018 signalled that the conservative neoliberal developmental model adopted by Putin’s administration back in the early 2000s will likely continue to dominate the Russian social security sector also in the future. This model tries to marry political authoritarianism with neoliberalism in the social and economic domains with the purpose of shifting the responsibility for the social well-being of the population onto the shoulders of individual actors. In that sense, the Russian neoliberal conservative trend in the sphere of old-age security is not different from the developments in some Western countries, suffice it to think of the policies of Thatcher and Reagan 30 years ago, which also supported the policies of welfare retrenchment, liberal labour reforms, and commercialisation and privatization of the public sector (Budraitskis, 2018).

About the Author

Elena Maltseva is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Windsor in Windsor, Canada. Her current research focuses on left-wing politics in post-Soviet states, social security reforms, and labour issues and regime stability in post-communist countries.

References

- Aasland, Aadne and Linda Cook (2016). “Russia Is Facing a Pension Dilemma as the Country Goes to the Polls’, EUROPP—European Politics and Policy, September 8; accessed at <http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/70269/1/blogs.lse.ac.uk- Russia%20is%20facing%20a%20pension%20dilemma%20as%20the%20country%20goes%20to%20the%20 polls.pdf>, October 5, 2018.

- Afanasiev, S.A. (2003). “Pension Reform in Russia: First Year of Implementing”, paper presented at the PIE International Workshop on “Pension Reform in Transition Economies”, Hitotsubashi University, Japan, February 22; accessed at <http://www.ier.hit-u.ac.jp/pie/stage1/Japanese/discussionpaper/dp2002/dp146/text.pdf>, October 5, 2018.

- Åslund, Anders (1995). How Russia Became a Market Economy, Washington D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

- “Bally s Vozu, Pensionnoi Sisteme Legche” [By removing the points system, the pension system will be doing better], Fontanka, June 18, 2018; accessed at <https://www.fontanka.ru/2018/06/18/107/>, October 5, 2018.

- Becker, Charles M., Grigori A. Marchenko, Sabit Khakimzhanov, Ai-Gul Seitenova, and Vladimir Ivliev (2009). Social Security Reform in Transition Economies: Lessons from Kazakhstan, New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bindman, Eleanor (2017). Social Rights in Russia: From Imperfect Past to Uncertain Future, Routledge.

- Bohlen, Celestine (2000). “Putin’s Team Hammers Out a Plan to Untwist, Level and Streamline Russia’s Economy”, New York Times, April 2; accessed at <https://www.nytimes.com/2000/04/02/world/putin-s-team-hammers-out-a-plan-to-untwist-level-and-streamline-russia-s-economy.html>, October 5, 2018.

- Buckley, C. and D. Donahue (2000). “Promises to Keep: Pension Provision in the Russian Federation”, in Mark G. Field and Judyth L. Twigg (eds) Russia’s Torn Safety Nets: Health and Social Welfare During the Transition, New York: St. Martin’s Press, pp. 251–270.

- Budraitskis, Ilya (2018). “How Conservative Is the Russian Regime?”, Open Democracy, August 8, 2018; accessed at <https://www.opendemocracy.net/od-russia/ilya-budraitskis/how-conservative-is-the-russian-regime>, October 4, 2018.

- Carstensen, Martin B. and Vivien A. Schmidt (2015). „Power Through, Over and In Ideas: Conceptualizing Ideational Power in Discursive Institutionalism”, Journal of European Public Policy 23 (3): 318–337.

- Cook, Linda J. (2007). Postcommunist Welfare States: Reform Politics in Russia and Eastern Europe, Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

- De Castello Branco, M. (1998). “Pension Reform in the Baltics, Russia, and Other Countries of the Former Soviet Union (BRO)”, IMF Working Paper No. 98/11, February, pp. 1–40; accessed at <https://ssrn.com/abstract=882230>, October 5, 2018.

- ‘Gref: Rossia Popadet v ‘Demograficheskuiu Iamu’”, Lenta.ru, July 21, 2000; accessed at <https://lenta.ru/ news/2000/07/20/gref/>, October 5, 2018.

- International Monetary Fund (2017). “Rossiiskaia Federatsiia: Doklad Personala dlia Konsu'tatsii 2017 goda v sootvetstvii so stat'iei IV” [Russian Federation: Internal Report ahead of the 2017 Consultation in accordance with Article IV]; accessed at <https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/.../CR/2017/.../cr17197r.ashx>, October 5, 2018.

- Kivinen, Markku and Terry Cox (2016). “Russian Modernisation—A New Paradigm”, Europe-Asia Studies 68 (1): 1–19.

- Kulikov, Sergei (2011). “Dlia Pensionerov Pridumali Osobyi Institut” [A new institution for pensioners was developed], Nezavisimaia Gazeta, April 8; accessed at <http://www.ng.ru/economics/2011-04-08/4_pensia.html>, October 5, 2018.

- Liutova, Margarita (2015). “Medvedev Ob''iavil Rezul'taty ‘Burnykh’ Obsuzhdenii o Nakopitel'noi Pensii” [Medvedev announced the results of the heated discussions about the funded pension], Vedomosti, April 23; accessed at <https://www.vedomosti.ru/economics/articles/2015/04/23/medvedev-obyavil-rezultati-burnih-obsuzhdenii-o-nakopitelnoi-pensii>, October 5, 2018.

- “MVF Porekomendoval Rossii Povysit' Pensionnyi Vozrast” [The IMF advised Russia to raise retirement age], Moskovskyi Komsomolets, January 12, 2017; accessed at <https://www.mk.ru/economics/2017/01/12/mvf-porekomendoval-rossii-povysit-pensionnyy-vozrast.html>, October 5, 2018.

- Orenstein, Mitchell A. (2008) Privatizing Pensions: The Transnational Campaign for Social Security Reform, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- “Pensionnaia Reforma 2002 Goda” [The 2002 pension reform], NPF Soglasie-OPS; accessed at <https://www. soglasie-npf.ru/directory/pension-reform/reform-2002.php>, October 5, 2018.

- Remington, Thomas F. (2015). “Pension Reform in Authoritarian Regimes: Russia and China Compared”, unpublished paper; accessed at <http://polisci.emory.edu/home/documents/ papers/pension-reform-%20authoritarian-regimes.pdf>, October 5, 2018.

- “Russia Introduces Law to Raise Retirement Age for State Officials to 65”, Reuters, October 31, 2015; accessed at <https://www.reuters.com/article/russia-economy-pensions/russia-introduces-law-to-raise-retirement-age-for-state-officials-to-65-idUSL8N12V08120151031>, October 5, 2018.

- Seitenova, Ai-Gul S. and Charles M. Becker (2004). “Kazakhstan’s Pension System: Pressures for Change and Dramatic Reforms”, Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics 45: 151–187.

- “Sofinansirovanie Pensii” [Pension co-financing], NPF Soglasie-OPS; accessed at <https://www.soglasie-npf.ru/ pension/co-financing.php>, October 5, 2018.

- “What Russia Wants: Vladimir Putin’s Long, Hard Haul”, The Economist, May 16, 2002; accessed at: <https://www. economist.com/news/special-report/1131280-relations-between-russia-and-west-have-rarely-been-better-what-does-it-mean>, October 5, 2018.

- Williamson, John B., Stephanie A. Howling, Michelle L. Maroto (2006). “The Political Economy of Pension Reform in Russia: Why Partial Privatization?”, Journal of Aging Studies 20 (2): 165–175.

- Wilson Sokhey, Sarah (2015). “Market-Oriented Reforms as a Tool of State-Building: Russian Pension Reform in 2001”, Europe-Asia Studies 67 (5): 695–717.

Russian Pension Reform: The Rise and Failure of Organized Protests

Irina Meyer (Olimpieva), Center for Independent Social Research

Abstract

This article examines the recent splash in organized popular protests in Russia caused by the government’s decision to increase the pension age. The focus is on the role of trade unions in organizing and leading the anti-reform protests. Using the perspective of industrial relations and the model of political exchange, the article explains why organized protests led by trade unions have little capacity to affect social policy in Russia.

Increasing the Pension Age

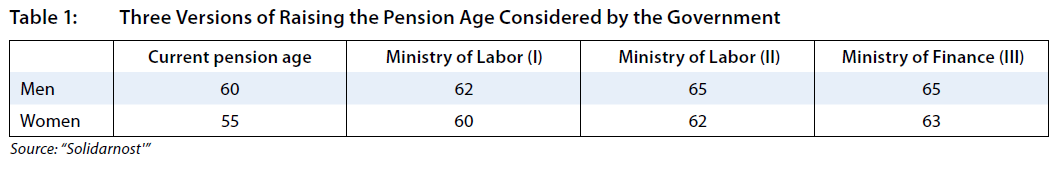

On the 14th of June, the Russian government approved a new bill raising the retirement age from 60 to 65 for men and from 55 to 63 for women. According to the main trade union media source Solidarnost', the government was choosing between three versions of the reform (see Table 1 on p. 16). The first two were suggested by the Ministry of Labor. The third and the toughest one was suggested by the Ministry of Finance and was eventually adopted by the government.

While increasing the pension age has long been discussed in governmental circles, the bill appeared as a complete surprise for ordinary people. According to Levada Center polls, about 85 percent of the population expressed their discontent with the pension reform. People felt betrayed and offended, especially because the reform appeared only a month after President Vladimir Putin announced his post-election “May presidential decrees,” promising to raise the living standards of ordinary people.

Pension Reform: Major Criticisms

Although the reform is widely advertised by the government as a measure to improve the well-being of Russian pensioners, the experts see it mostly as “accounting maneuver” of the government aimed at extracting money from the population to replenish the shrinking state budget. The bill adopted by the government concerned only raising the retirement age without taking into account a wide complex of related problems, such as, the inevitable growth of unemployment and age discrimination at the workplace, the profound restructuring of the vocational training and healthcare systems, and many others. Some experts even refused to consider the proposed bill a reform, adopting alternative labels such as the “so-called reform.”

Another major criticism of the reform refers to its hastiness. Usually, social projects of this kind are planned looking forward 5–10 years, because they affect the long-term life strategies of all categories of the population. In the case of Russia, the bill will come into force already in January 2019 (which allegedly confirms that the primary aim of the reform is to find missing funds for the implementation of the “May presidential decrees”). Although the bill implies a transitional period during which the pension age would be increased gradually, the reform would dramatically affect people of the pre-pension group who plan toexp retire in the next few years.

From the socio-demographic perspective, raising the pension age is not justified because of the low life expectancy of the Russian population, especially among men. According to the Federal State Statistics Service, in 2016 the average life expectancy of the male population was 66.5 years. The majority of the male population in 21 out of 85 federal districts is not expected to reach the age of 65.

Another reason for criticism is the selective character of the changes and unjustified inequality in pension benefits among different social groups. For some state employees, working in the military and law enforcement systems including the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, FSB, Rosgvardiya, MChS and others, the retirement age remains 40–45. The difference between these privileged groups and the rest of the population becomes even more striking with the new bill. Besides, there is a gap in the levels of pension benefits, which is also left intact by the reform. According to some external pageexpertscall_made, pension reform was deliberately designed to “buy” the loyalty of the groups supporting the regime.

Raising the retirement age is framed by the government as the only possible way to maintain the existing pension system. According to Labor Minister Labor Maxim Topilin, without raising the retirement age, the Russian pension system will have to stop indexation of pensions in two years. Meanwhile, experts suggest many other ways for solving this problem, particularly improving pension fund management and reforming the pension system as a whole.

A no less serious claim is that the pension reform was developed in the Kremlin corridors and was not the result of any public discussion.

The Splash of Anti-Reform Protests: June–July

Trade unions were the first to call for the all-Russia anti-reform protests. After the bill was submitted to the State Duma, the Federation of Independent Unions of Russia (FNPR), which is usually referred to as a collection of “official unions,”1 encouraged regional and local trade unions to organize meetings, pickets, rallies and other collective actions against the pension reform.2

The Russian Confederation of Labor (KTR) initiated the antireform petition that collected over 2 million signatures in only 3 days. Inspired by this success, some KTR leadersexternal pageexpressedcall_made assurance that mass organized protests could influence and even stop the pension reform.

The political opposition, both systemic and non-systemic, also disagreed with raising the pension age. Local branches of the Communist Party, Yabloko, LDPR, and Just Russia participated in multiple meetings and rallies organized by trade unions in the regions. On July 1, the headquarters of Alexei Navalny initiated protest actions in 40 Russian cities, many of which were joined by the representatives of systemic parties and trade unions.

According to KTR, by the middle of July, more than 140 protest actions had taken place in 100 Russian cities with about 65,000 participants. The most large-scale actions took place in Omsk (3,000 people), Astrakhan (2,000 people), Arzamas (1,500 people), and Barnaul (1,000 people).

The leadership of the trade unions for these events predetermined some features of the anti-reform campaign, making it different from previous protest actions. The first distinguishing feature was the organized character of the protests. There were almost no spontaneous gatherings or non-sanctioned meetings. In 60 cities the meetings did not take place because they were not allowed by the authorities (mostly because of the World Cup championship being held in Russia then). Until the end of summer, there were almost no police interventions in protest actions or arrests of the participants. Another interesting feature was the wide geographical extent of the protests. Usually protests take place in Moscow and other major Russian cities. In the case of the anti-reform campaign, due to the mobilization capacity of trade unions, the protests were held all over Rus sia, including in big and small cities some of which had never conducted any protest actions.

Overall, the protests demonstrated the unprecedented unanimity of all political groups. Both official and alternative trade unions expressed their disagreement with the reform, and the systemic and non-systemic opposition held joint anti-reform meetings and rallies.

However, despite the unprecedented scale and unanimity of the protests, the bill passed the first reading in State Duma on July 19 without any changes. The period for submitting amendments was extended until September 24.

August–September

The anti-reform protests continued through August and September. According to the Russian Confederation of Labor, during the summer, 465 protest actions took place in 281 Russian cities, with approximately 225,000 participants.

At the end of the summer, as the gubernatorial elections in the regions were approaching, the opposition political parties kicked their anti-reform activity into high gear, trying to improve their electoral positions. The communists (KPRF) announced that they would take the lead in the anti-reform campaign and called for an all-Russia referendum. On September 2, the KPRF organized several anti-reform rallies with the biggest one in Moscow that attracted about 9,000 participants. On September 9, the protests organized by Aleksey Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation took place in over 40 Russian cities. As a result, about 800 people were arrested since most of these protest actions were not approved by the local authorities.

While the attention of the media and the public refocused on the political opposition, trade unions continued using various legal instruments of public influence in an effort to influence the pension reform. KTR continued collecting signatures for its anti-reform petitions. On August 21, FNPR leader Mikhail Schmakov presented trade union criticism of the pension reform at the extended parliamentary hearings in the State Duma. However, by the day of the hearings, it became clear that raising the pension age was already a done deal and the fight could only be over amendments to soften the bill.

On August 29, President Vladimir Putin finally made a direct appeal to the Russian people, asking them to support the pension reform. As expected, he suggested some amendments to moderate the bill, such as, reducing the increase in the pension age for women to 5 years, from 55 to 60, because, as he put it, “In our country, there is a special, gentle attitude to women.” As was also expected, all nine amendments suggested by the president were accepted by the Duma Committee on Labor and Social Policy and unanimously approved by the parliament on September 26 when the bill was accepted in the second reading. On September 27, the bill on increasing the pension age was finally adopted by the State Duma in the third and final reading.

The government has ultimately adopted a more moderate version of the pension reform which had probably been planned from the very beginning. However, this softening of approach was presented not as the result of mass popular protests organized by the trade unions, but as a mercy bestowed by the president.

Organized Protests, Social Partnership, and Political Exchange

Organized union-led protests are a key element of the social partnership system (SPS), which provides institutionalized cooperation between trade unions, employers, and governments. In European countries, which serve as a prototype for the Russian SPS, the relations between trade unions and the state are based on the principles of “political exchange” meaning that trade unions restrain protests in exchange for keeping the interests of labour in social policy. Trade unions resort to organized protests to exert public pressure on policymakers when negotiations between social partners fail or their results are not satisfactory for the unions.

At first glance, the anti-reform protests in Russia perfectly fit the social partnership model. FNPR called for all-Russia protest action after it failed to contest the bill at the meeting of the Russian Trilateral Commission (RTC), which is the supreme institute of social partnership in Russia. The protests, organized by trade unions, encompassed most of the Russian regions and different localities; they did not pose any political demands; and the FNPR strove to ensure that the protests strictly complied with legal regulations. In fact the pension effort was the first all-Russia protest action organized by trade unions since the 1990s. Nevertheless, it failed to stop or even essentially affect the pension reform.

The attempts of the trade unions to influence the pension reform undertaken within the framework of the social partnership model would have had better results had they been realized in a different political environment. While in democratic systems the main addressee of organized protests is the elected lawmaking institutions (such as parliaments), in Russia, the key policymaking decisions are made by the Kremlin. In order to force the Kremlin to stop pension reform, the protests would have had to become unruly riots (as happened in 2005 when the spontaneous unrest of pensioners against the monetization of the in-kind benefits they received (l'goty) forced the government to suspend the reform), or create a direct threat to the political regime, which is not the case when trade unions lead the protests.

Trade unions in European countries are usually independent from the state. In Russia, the authoritarian character of the state and the lack of strong social democratic parties that could function as the political counterparts of European trade unions require the FNPR to seek alliances with the strongest players in Russian politics—the Kremlin and President Vladimir Putin.

The FNPR is known for its loyalty to the Kremlin and never encourages protest actions at the grass-root level. That is why the open call for the all-Russia anti-reform protest by FNPR leader Michail Schmakov looked quite unusual. According to Vedomosti, the union-led protests were in fact “manipulated” or “controlled” by the Kremlin, meaning that the FNPR was allowed by the Kremlin to spearhead the protests to reduce the political risks of uncontrolled protest. However even if there was no agreement between trade unions and the Kremlin the protests still would not be able to stop the reform. As an instrument of public influence on social policy, organized protests can be effective only if they are complemented by democratic institutions, such as a democratically elected parliament, true political competition, and strong trilateral institutions of social partnership, which are lacking in authoritarian regimes like Russia’s. In the absence of these basic preconditions, the organized protests are turned by the regime into another imitation of democracy.

About the Author

Irina Meyer (Olimpieva) is a senior researcher at the Center for Independent Social Research in St. Petersburg. Currently she is a visiting scholar at the Aleksanteri Institute in Helsinki.

Recommended Resources

Link to external pageMap of Anti-Reform Protestscall_made in Summer 2018 from the Russian Confederation of Labor.

Notes

1 “Official unions” are trade unions affiliated with the Federation of Independent Unions of Russia (FNPR), the successor of the soviet trade unions uniting over 20 million employees. The FNPR is the main representative of organized labor interests in the Russian Trilateral Commission. The “alternative” trade unions are united by the Russian Confederation of Labor (KTR) representing about 700 thousand members. These unions usually emerge on the wave of labor conflicts, often spontaneously as the alternative to official unions when they are unable to defend interests of the employees.

2 For more information about the scale of the protests see monitoring of protest actions on the site of Solidarity newspapeexternal pager https:// www.solidarnost.org/topics/Profsoyuznaya_kampaniya_protiv_ povysheniya_pensionnogo_vozrasta_.htmlcall_made

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library