Subsidiarity and Swiss Security Policy

14 May 2018

By Matthias Bieri and Andreas Wenger for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in May 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Subsidiarity is an enduringly popular principle that ensures efficient, citizen-oriented political solutions. However, when applied, it also always entails a great deal of effort and a certain degree of vulnerability. As a way of compensating for these disadvantages, Switzerland’s security policy will in the future be characterized by constant dialog and pragmatic governance approaches.

The principle of subsidiarity requires that the state should only become involved where society is unable to cope unassisted, and that problems should always be dealt with at the lowest possible state level. Today, this maxim is encountered in a variety of debates involving such disparate topics as how to make the EU more responsive to citizens’ needs, how to order post-conflict societies, or how to preserve the Swiss system of federalism. In all these instances, subsidiarity is a prominent factor. However, implementing the principle of subsidiarity is not an easy matter. For subsidiarity to operate effectively, all tasks must always be clearly delegated to specific levels of government. In an increasingly networked world, this has obviously become more difficult.

In Swiss politics, the principle of subsidiarity has a long history. Since the creation of the federal state in the 19th century, it has been a part of the federal state model, embodying the notion that the state should be built from the bottom up. Switzerland’s security policy, too, rests on the subsidiarity principle. Traditionally, it has been based on a classic division of responsibilities. While external security comes under the purview of the federal state, and is thus primarily a matter for the armed forces, the cantons are responsible for domestic security. In this sphere, the federal level will only offer auxiliary, i.e., subsidiary support if the resources of the cantons are insufficient and they appeal to the federal administration for help. However, exceptions to this rule are becoming more and more common. Today, the federal administration handles numerous tasks, especially complex and cross-border assignments in the field of domestic security.

Observance of the subsidiarity principle brings inherent advantages and disadvantages. In the context of security policy, contemporary threats and dangers illustrate the intrinsic difficulties. Major challenges here are the rapid assessment of the seriousness of an incident and identification of links between distinct events. Moreover, jihadist terrorism is an example of how multiple levels of state authority deal with the same issue today. Cooperation between the authorities involved and coordination of tasks is thus an essential, but onerous requirement. Additional issues regarding the interface of state and society arise in the sphere of cyberspace. Although the new challenges are disparate, they too can be overcome; however, they require new, pragmatic approaches, which are already emerging today.

Inherent Pros and Cons

In the political context, “subsidiarity” has two main connotations. On the one hand, the term refers to a state only intervening when non-state actors are unable to cope with a situation. On the other hand, the principle of subsidiarity implies that a superordinate level of state bureaucracy will only become involved when the lower level is overextended. In Swiss federalism, both senses of the word are important. On the one hand, subsidiarity governs relations between the state and society; on the other, it is also the governing principle in the relationship between various state levels, i.e., between the federal administration, the cantons, and the communities.

Compared to centralist systems, the principle of subsidiarity has certain undisputed advantages. One of these is efficiency, since problems are to be resolved as closely to the source as possible. Low levels of the public administration are authorized to make decisions and find solutions. This ensures that no more resources than necessary are expended. Moreover, subsidiarity is designed to avoid duplication. If a problem exceeds the capabilities of one state level, it may call upon the resources of the next higher level. In this way, all levels have access to a shared reserve of resources that can be used to deal with challenges, with the highest level always serving as a reserve of final resort. Also, the principle of subsidiarity is based on the idea of a non-expansive state that economizes on resources.

The second advantage of subsidiarity is management coordination in close proximity to citizens. Measures should be taken by the level of administration that is best suited to do so, based on its knowledge of local conditions and its proximity to the consequences of decisions. This means that solutions can be designed quite individually. The example of Switzerland, where 26 cantons with population sizes ranging between 16,000 and 1.5 million are responsible for the same issues, illustrates that quite diverse solutions may be required.

However, subsidiarity also has disadvantages, especially when it comes to crisis management. Naturally, lower levels of administration may be overwhelmed by the extent of a crisis. If the authorities fail to recognize this early enough and do not call for assistance, the consequences may be far-reaching. Especially in the case of rapidly escalating crises, subsidiary structures may obstruct timely responses. If several crises of varying intensity occur at the same time, the need for a unified command responsibility may be realized too late. Moreover, each case of subsidiary activity requires a great deal of coordination, which may again obstruct crisis management and involve considerable effort. For instance, in Switzerland, the cantonal authorities retain overall operational command in all cases involving domestic security. In such a situation, the use of federal resources under the operational management responsibility of cantonal authorities may constitute an additional challenge.

Difficult Separation of Tasks

Since the end of the Cold War, the principle of subsidiarity and the separation of tasks have changed considerably in the field of security policy. New threats have emerged, and (military) conceptions of threat have shifted accordingly. Threat pictures below the threshold of war have therefore increased in importance for external security. This has contributed to a situation where the distinction between internal and external security threats has become increasingly blurred.

In Swiss security policy, this difficult delimitation, together with other factors, contributed to an increase of problematic task referrals to the federal level from the 1990s onwards. At the start of the 2000s, this undesirable development gave rise to a debate, which in turn led to a review of tasks and responsibilities in domestic security. While this review essentially confirmed and strengthened the subsidiarity principle, it did not find an enduring solution to the problem of allocating responsibilities. The incongruity between the constitutional obligations of the cantons, which were under financial pressure, and the apparently unused potential capabilities of the federal administration persisted for the time being. It was only a decade later that a series of reforms led to sustainable solutions that were satisfactory to all parties. On the one hand, certain irregularities were eliminated. For example, permanent missions of the armed forces in support of civilian authorities will soon be a thing of the past. On the other hand, legislation was adapted to real-life practices. This involved establishing a legal basis for the armed forces’ assistance missions. The military is now authorized in principle to support the cantons in coping with extraordinary peaks in demand even if no extraordinary crisis situation has been declared. On the one hand, from a constitutional perspective, this means that a violation of the subsidiarity principle persists in certain areas. However, jurisdictions and responsibilities in the sphere of domestic security have been clarified, setting the course for the future and suiting the requirements of all parties involved.

Multi-Actor Formats Become the Rule

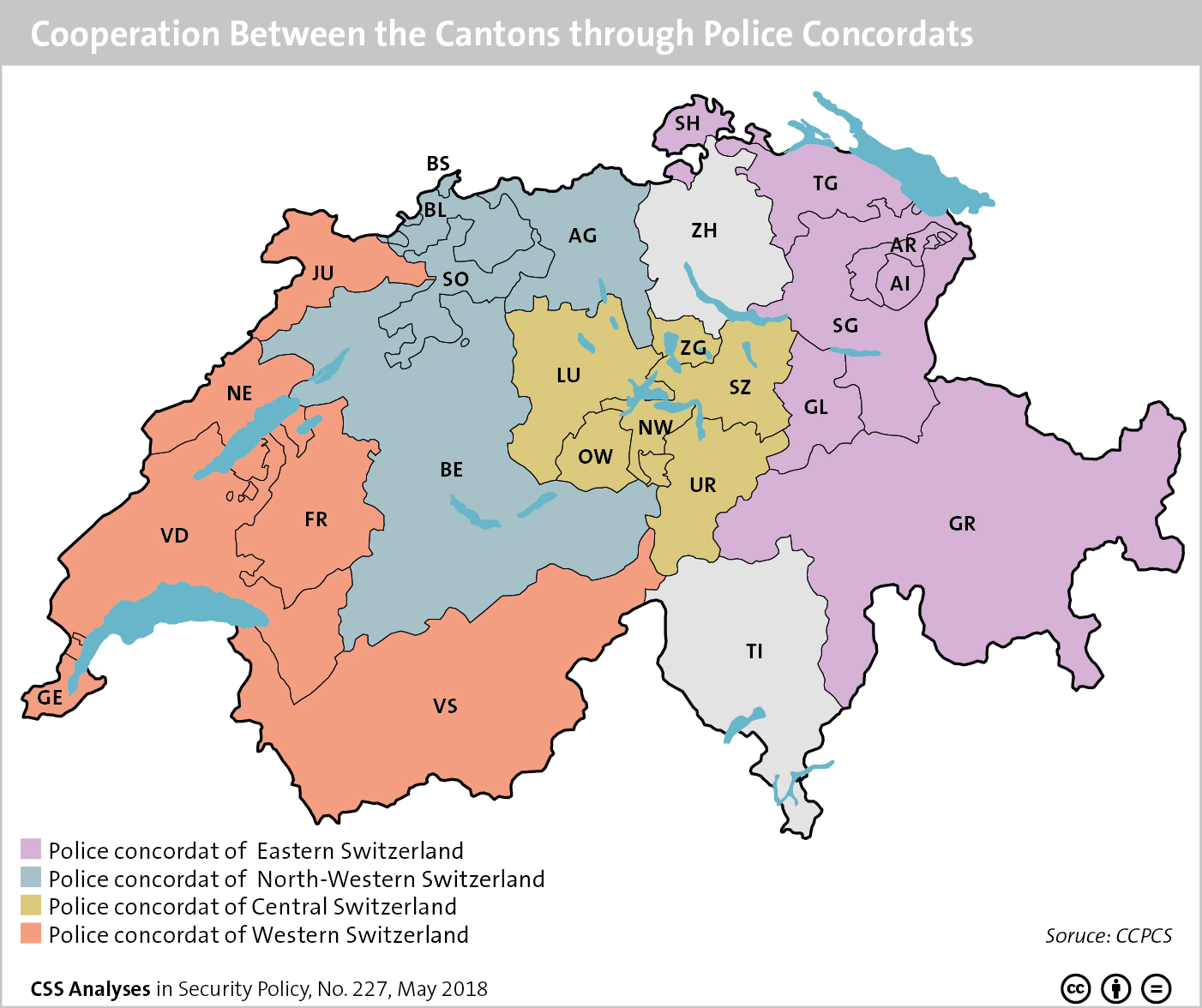

Today, the most pressing issues relating to the subsidiary order arise in connection with new challenges for the security police, which comes fully under the jurisdiction of the cantons. The focus here is on the growing number of joint tasks. The cantons increasingly cooperate horizontally and are thus able to support each other in various ways without having to involve the federal government in a subsidiary way. Specifically, this cooperation is governed by the regional police concordats (see map) and the agreement on inter-cantonal policing missions (IKAPOL). At the same time, due to persistent austerity measures, there are still incentives for ceding responsibility in return for financial support from the federal administration.

Recently, contacts between the cantons, the federal administration, and international partners have increased immensely. The security policing efforts of the cantons have become more internationalized in recent years, not least due to Switzerland’s accession to the Schengen/Dublin Agreement in 2008 and the increasing international dimension of crime in a globalized world. Due to efficiency and coordination considerations, the Federal Office of Police (fedpol) is responsible for national and international police cooperation and therefore serves as the central point of contact for all criminal police reports sent by Interpol, Europol, and as part of the Schengen Agreement. Additionally, this federal department is generally responsible for cross-border and complex serious crimes, further accentuating the role of fedpol. Of course, these tasks all require constant liaison with the cantonal authorities. In this way, the overall relationship between fedpol and the cantonal police forces has noticeably increased in importance.

The relationship between the cantons and the armed forces has also changed. They increasingly have to deal with similar issues, such as scenarios for terrorist attacks, which also involves exchange and coordination. An example of this is the expanded conception of defense that is crucially important in determining the threats for which the armed forces must prepare. As stated in the Security Policy Report 2016, whether a state of defense is in force, and thus whether the armed forces can be deployed for the protection of external security, today no longer depends exclusively on the source and means of an attack, but also on the intensity and extent of an attack. This means that even an attack by a non-state actor may lead to a defense mission for the armed forces. While that is not a complete reinterpretation of the concept, a state of defense of this kind was not conceivable in the past. As a result, the army today also deals with threats that in the past would only have been of concern to the cantons.

Jointly Against Terrorism

Counter-terrorism is a tangible example of how cooperation pressure and joint domestic security tasks have become more important. Here, the notion that various levels of government should be responsible for the same threat phenomenon is nothing unusual. Networking between federal and cantonal authorities and close cooperation with European security institutions are essential. For example, investigations of jihadist terrorism come under the jurisdiction of the Federal Criminal Police, being considered a serious crime. However, in the case of an event, it has no response capabilities, since the cantons have jurisdiction. The latter, for their part, in 2015 created a national police command staff to improve the management of supra-regional events of relevance to the police in case of a terrorist attack. In the case of an event, this staff would support the cantonal command structures that have territorial responsibility and coordinate collaboration at the national level. The cantons are also responsible for prevention of jihadist radicalization, with the federal authorities being merely authorized to offer recommendations. On the other hand, the federal authorities are involved in international policymaking on this topic. Therefore, an exchange with the cantons is appropriate in this sphere, too.

Overall, there is therefore a considerable need for coordination. To this end, TETRA, Switzerland’s national operations coordination body in the area of counterterrorism, has been transformed from a task force into a permanent institution. However, coordination platforms for dealing with complex security challenges can be found at various levels. In 2011, the Swiss Security Network (SSN) was created as a platform for basic coordination between the federal and cantonal authorities in the field of security. In the meantime, it has come to be used for a broad range of issues. The SSN is also the framework for joint exercises that deliver insights on operational coordination in case of a crisis. This focus on operational practices is especially valuable because it is in a crisis, when a lack of coordination could have devastating consequences in the context of subsidiary structures.

The Role of Private Actors

In the context of security policy, the second meaning of subsidiarity – limiting state intervention to those areas that private actors are unable to manage unaided – is also gaining importance. A good example of this is cyberspace. external pageThe National Strategy for the Protection of Switzerland against Cyber Risks (NCS 2018 – 2022)call_made, which was jointly developed by the federal and cantonal authorities as well as the private sector, emphasizes the subsidiary role of the state in this area. Individual responsibility is singled out as an important principle. Nevertheless, protection from cyber-risks is regarded as the shared responsibility of the corporate sector, society, and the state. Pursuant to this strategy paper, the state may intervene with support, incentives, or regulations.

According to the NCS, the aim is to strengthen collaboration between the federal government, cantons, and the private sector. This implies a special role for public -private partnerships. Both on the state side and in the private sector, a clear delineation of tasks and roles is essential. However, since cyber-risks affect nearly all areas of life, the economy, and the public administration, and since at the same time these threats develop very dynamically, such a delineation is in itself a challenge. Therefore, joint solutions will be required in this field, too. For example, the SSN coordinates the implementation of the NCS at the cantonal, municipal, and community levels. Moreover, a coordinating body for implementing the NCS is established that will consist of federal, cantonal, and corporate representatives.

For the cantons, the main focus is on the topic of cybercrime. This is a challenge for many cantons that have fewer resources for dealing with the issue. Therefore, the federal administration and the cantons are planning between three and four centers of competence for cybercrime that will facilitate the exchange of information and access to expertise.

In areas that go beyond crime, the concentration of government know-how and resources with the federal administration is uncontested. With a view to the growing number of cyberattacks, permanent structures are to be established in this area too, so as not to have to rely on ad-hoc solutions, as was the case in the past. However, these fixed structures will also be characterized by broad inclusion.

The Federal Department of Defence, Civil Protection and Sport (DDPS) has a distinct role to play in matters relating to cyberspace. While the Federal Department of Finance (FDF) has the lead within the federal administration in matters pertaining to information technology, and cybersecurity is generally a matter for all government departments, the DDPS and its Federal Intelligence Service (FIS) nevertheless play a distinct part due to the singular importance of intelligence matters. Moreover, through the Federal Office for Civil Protection (FOCP), the DDPS deals with critical cyber-infrastructures that require special protection. In addition, the Swiss armed forces with their considerable means and personnel are also engaged in the response to cyber-threats.

One of the tasks of the armed forces is to serve as a strategic reserve for the civilian authorities, including in cyberspace. Therefore, it is important to establish when and under which conditions the subsidiary role takes effect and which resources the cantons can be counted on to deploy. The army must be able to close the remaining gaps, and in doing so, it can take recourse to the expertise it has built up for the protection of its own systems. However, the question is how intensively the army should prepare for subsidiary missions and for the event of a cyberattack.

Thus, the complex sphere of cyberspace requires a great deal of coordination domestically, involving a great many actors; but it also requires much in the way of cross-border coordination. Here, we may draw similar conclusions as in the case of counterterrorism. Like terrorist attacks, cyber-incidents usually do not occur in isolation, but in coordinated surges. Therefore, efficient crisis management in this area also requires that cooperation and coordination in such scenarios be constantly developed.

Fit for the Future

Increasing international links, the growth of transnational security policing threats, and the increasing importance of private actors in dealing with them have created new requirements within the subsidiary system. In the future, the need for flexible and pragmatic solutions will become even stronger. Managing complex threats in a multi-actor format will become the rule. Coordination must be commensurate to the situation and to the problem, as illustrated by the example of counterterrorism. The focus is no longer on the constitutional allocation of responsibilities, but on the concrete contribution that each level can make towards resolving a problem.

In matters pertaining to cyberspace, partnerships between private operators and state authorities are becoming more and more important. At the same time, it is the federal administration that, for the foreseeable future, can mobilize the most resources in support of the private sector. Consequently, it would be involved at an early stage of a crisis. There are other, similarly complex issues where the federal level is tasked with special duties or is involved in a subsidiary function at an early stage. Given the effort required to prepare for such cases, this is an eminently sensible approach. At the same time, it is all the more important that the cantons, communities, and society at large be assigned responsibilities in those areas where they have the means for dealing with problems. The creation of centers of competence in this area can lay the groundwork for other security-related policy fields.

Based on these insights, it appears that the hierarchical structures of subsidiary security policy seen in the past will be replaced by more flexible ones. These new structures will be aligned with the threat picture at any given point and based on the concrete contributions that the parties involved can make. In this process, the involvement of the private sector and of society at large will become increasingly natural.

About the Author

Matthias Bieri is a Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zürich. He is, amongst others, the author of Military Conscription in Europe: New Relevance (2015).

Prof. Dr. Andreas Wenger is Professor of International and Swiss Security Policy at ETH Zurich and Director of the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.