EU Policy Options Towards Post-Soviet De Facto States

22 Nov 2017

By Urban Jakša for Polish Institute of International Affairs (PISM)

The this article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by external pageThe Polish Institute of International Affairscall_made on 19 October 2017.

EU Policy Options towards Post-Soviet De Facto States

Conflicts in post-Soviet areas involving de facto states have remained unresolved since the ceasefires in the early 1990s. By heating up periodically, these conflicts threaten broader regional security, and by remaining unresolved, limit their chances for political association and economic integration with the EU, undermining the Union’s Eastern Partnership. In recent years, the EU’s tensions with Russia, the ever-growing dependence of most post-Soviet de facto states on Russia, the recent re-escalation in Nagorno-Karabakh, and recently emerged, protracted conflict in eastern Ukraine have made the situation more complicated and urgent. Since the EU’s current approach towards these “frozen conflicts” has so far shown little result, the EU and the V4 should take a more active role in resolving these conflicts and might want to consider stepping up engagement with the post-Soviet de facto states. Increasing the interaction and extending its scope while at the same time reassuring the parent states that this will not constitute “de facto recognition” would de-isolate the populations of these territories, reduce their dependence on Russia and provide incentives for conflict resolution.

De Facto States in the Post-Soviet Space

According to one of the most widely adopted definitions, de facto states1 are “territories that have achieved de facto independence, often through warfare, and now control most of the area upon which they lay claim. They have demonstrated an aspiration for full de jure independence, but either have not gained international recognition or have, at most, been recognised by a few states.”2

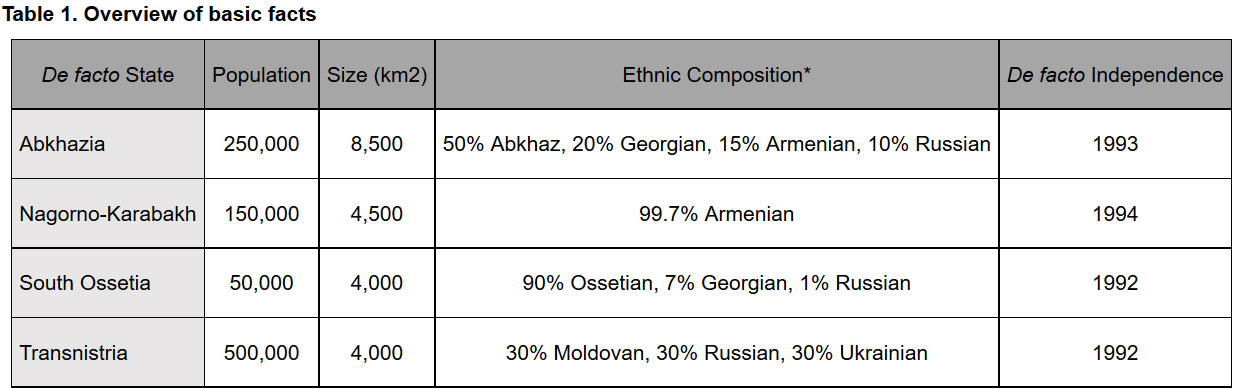

The emergence of the four post-Soviet de facto states—Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria—is inseparable from the armed conflicts from which they emerged in the context of the “broader process of disintegration of the Central and East European political, economic and security system”3 as a result of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. These unresolved conflicts4 have in turn become protracted5 and remain hot6 (especially in Nagorno-Karabakh)7 or at least simmering,8 although the journalistic cliché “frozen conflicts”9 is often used outside expert communities. These conflicts are, however, far from frozen and present a consistent threat to regional security10 while undermining territorial integrity, and thus hinder the democratic reforms in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine and their closer political association and economic integration with the EU. This has become even more evident since the Russian military intervention in Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea, and support for the rebels in Donbas since 2014, and the renewed hostilities in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in April 2016.

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was the first, fought between Armenia and Azerbaijan from 1988 until May 1994, when a shaky bilateral ceasefire was put into place, leaving Armenians (an overwhelming ethnic majority in the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast within Azerbaijan) in control of the territory as well as some adjacent areas of Azerbaijan proper while its status remains disputed and negotiations continue within the format of the Minsk Group (under the co-chairmanship of France, Russia, and the U.S.). Compared to other conflicts in the region, the war between the pro-Transnistria and pro-Moldovan forces did not have a distinct ethnic character and lasted four months in 1992. The number of casualties and refugees/internally displaced persons (IDPs) generated by this conflict was lower than in the other three conflicts. Transnistria was recognised as a party in conflict and negotiations on its status continue in the format of the “5+2” talks involving Transnistria, Moldova, Ukraine, Russia, and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), plus the U.S. and the EU as external observers. Wars in South Ossetia in 1991–1992 and Abkhazia in 1992–1993 broke out after Georgia declared independence and attempted to reassert control over the territories within its internationally recognised borders. The war in Abkhazia differs from other post-Soviet conflicts as it was the only Soviet republic in which the titular nation striving for independence—the Abkhaz—comprised less than 20% of the population in the multi-ethnic Abkhazian ASSR. It was also particularly bloody and resulted in the deaths of an estimated 10% of the Abkhaz population as well as in the displacement of at least 200,000 ethnic Georgians.

Post-Soviet de facto states are small in terms of territory, population, and the economic power and influence they possess. With their violent past, de facto states were for a long time seen as black holes, zones of illegality and organised crime, run by warlords and riddled with corruption,11 having to battle the stereotypes associated with the lack of recognition of their sovereignty since “without sovereignty, anarchy is assumed.”12 Despite being initially seen as temporary geopolitical anomalies, the post-Soviet de facto states have gradually become a semi-permanent fixture, necessitating policymakers acknowledge and engage with them, even if diplomatic recognition is ruled out.

Evolving Realities and Perceptions

The realities in de facto states have changed much since the early 1990s when these entities emerged victorious out of secessionist conflicts, but impoverished and often warlord-run. By the early 2000s, there was a growing realisation among European scholars and policymakers that these were no longer temporary “black holes,” but that through intense state-building, they had managed to establish most trappings of statehood. There were greater calls for EU engagement and democracy promotion in post-Soviet de facto states after Russia and a handful of its allies recognised Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008.13 De facto states were no longer vilified and there was a growing awareness of their diversity. Things changed again after new actors who seem keen on abusing the state form appeared on the world stage: People’s Republic of Donetsk, People’s Republic of Lugansk. All post-Soviet de facto states are now again being re-cast in the light of efforts to build state-like entities in Donbas, being once again seen as instruments of Russian foreign and security policy and its growing geopolitical ambitions. Because this one-size-fits-all characterisation of post-Soviet de facto states as Russian puppets or satellites is at worst wrong and at best lacks nuance, it calls for a reassessment of the status, role, dependence, and prospects of engagement with these entities. An even more pressing reason for the reassessment is that not only did the EU’s policy of “engagement without recognition” not produce the desirable effects, but that the conflicts deemed by many as frozen can—and do (as the re-escalation of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh in April 2016, which caused more than 200 deaths on both sides)—heat up, threatening broader regional security.

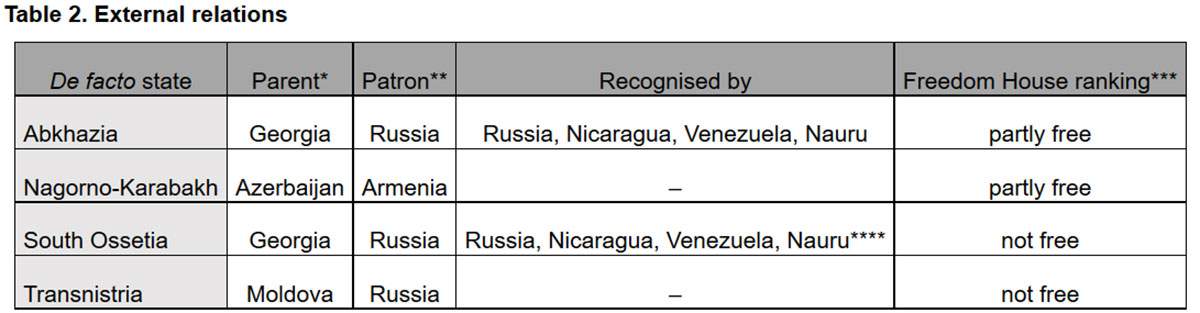

If we put political regimes of de facto states in their post-Soviet context, they do not stand out all that much.14 When it comes to democracy and freedom, their parent and patron states are often not in much better shape. When Abkhazia seceded in the early nineties, Georgia was a haven for organised crime and mafia ran a significant part of the economy. Corruption and smuggling are a problem in Transnistria as they are in Moldova. According to Freedom House,15 Nagorno-Karabakh—which seceded from Azerbaijan—is considered partly free, as opposed to its parent state Azerbaijan, which is considered not free. Abkhazia ranks higher than Russia (partly free compared to not free) and in 2011, a pro-Russia candidate, Raul Khajimba, notably lost the elections (albeit winning the next election and currently in power), proving that domestic politics in de facto states are far from predictable.

De facto states suffer from too little and too much attention simultaneously: lack of attention from the wider international community and excess attention from the “patron states” on which they depend for their survival.16 Effectively isolated, they are easy prey for regional powers seeking to monopolise their relations17—namely Russia.18 In some de facto states, such as Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Transnistria, the “chaos of war became transformed into networks of profit”19 that have a stake in perpetuating the protracted conflicts. Post-Soviet de facto states experience tension between “competition and pluralism entailed by democracy and the claim to homogeneity contained in the nationalist discourse.”20 21

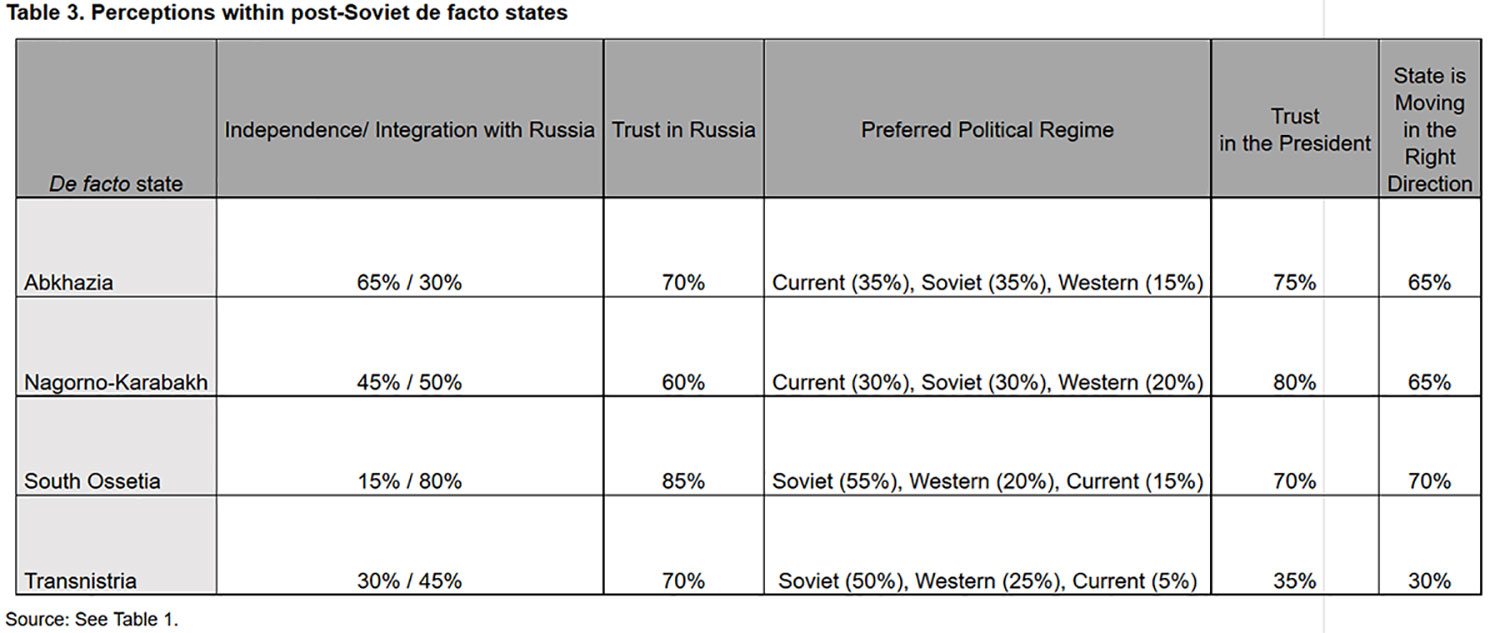

Perhaps the most interesting and policy-relevant set of perceptions are those of the populations in de facto states towards their political system, status, and attitudes towards Russia, which can give an indirect clue as to what kind of engagement is possible. In Abkhazia and South Ossetia, close to 70–85% trust in the Russian leadership, 70% in Transnistria, and 60% in Nagorno-Karabakh, while the support for the presence of Russian troops in Abkhazia and South Ossetia is around 80% and in Transnistria below 60%. In Abkhazia and South Ossetia, 65–70% believe the state is moving in the right direction, in Nagorno-Karabakh it is two-thirds, and only a third in Transnistria. Trust in the president of the republic stands at about 75% in Abkhazia, close to 70% in South Ossetia, around 80% in Nagorno-Karabakh and only around 35% in Transnistria. Abkhazians overwhelmingly favour independence (65%) to integration with Russia (30%), while 80% of Ossetians favour the latter. In Transnistria, the electorate is split, with a slight preference for integration with Russia. In South Ossetia and Transnistria, half of the population believes the Soviet system to be the best political system, about a third in Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh. One third of the population supports the current system in Abkhazia and Nagorno-Karabakh, but only 15% in South Ossetia and a mere 5% in Transnistria. Generally, between 15% and 25% of the population prefers Western democracy, the percentage being the highest in Transnistria (25%) and the lowest in Abkhazia (15%).22

The perspectives of de facto states on engagement with the EU vary case-by-case. Abkhazia has in the past shown most interest in engagement, especially after Russian recognition, but most of that enthusiasm seems to be gone and Abkhazia has forged closer relations with Russia after the pro-Russian Raul Khajimba assumed the presidency in 2014. Nevertheless, some elements conducive to engagement still exist. Civil society in Abkhazia remains vibrant and interested in EU engagement. Transnistria’s population is disappointed with its political system, people lack trust in the president and a third of the population prefers Western democracy. It exports more goods to the EU (through Moldova) than to Russia. Closer engagement based on economic interests seems more plausible than engaging with Transnistria’s governmentally co-opted civil society. South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh are influenced by their proximity to their kin states: North Ossetia as part of the Russian Federation and Armenia. Most of their foreign interaction is conducted through these patron states, so increased direct engagement is less viable.

The EU’s Evolving Approach to Post-Soviet De facto States

The Helsinki Final Act and the Paris Charter form the legal basis for relations between states in Europe, reaffirming principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, peaceful settlement of disputes, and inviolability of borders. In line with these principles, the EU has consistently supported the territorial integrity of Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine and refused to recognise the breakaway regions as independent states. While its stance has remained unchanged, the EU’s approach to these entities has evolved from low-profile involvement throughout the 1990s to a greater role in conflict resolution and promotion of positive social change through “engagement without recognition.” The EU has a strong interest in conflict management and resolution in its Eastern Neighbourhood. Re-heating these conflicts could destabilise the region, result in loss of human life, humanitarian crises, and trigger additional refugee flows. Furthermore, the conflicts effectively undermine territorial integrity and block Georgia, Moldova, Azerbaijan, and now Ukraine from pursuing their aspirations of Euro-Atlantic integration. Despite their diversity and the fact that post-Soviet de facto states are not all Russian puppet states, the territories of Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria—all economically dependent on Russia and hosting its military bases—could (and some have in the past) be used as a staging ground for military operations directed against Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries.

The Visegrad Group’s (V4) interest in post-Soviet de facto states should be based on their strategic interest in defending a security architecture based on the principles agreed in Helsinki. The V4 will be more affected by the area of instability in its neighbourhood than other EU countries. Even if V4 members sometimes demonstrate a different approach to Russia, they should be interested more than the others that the EU defends those values and remains a normative power. The V4 countries for a majority of post-Soviet countries still represent powerful examples of the positive transformative power of European integration and can act as models emulated by the EaP countries. The V4’s interest in the EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood and the V4 countries’ experience of economic and political reform call for the greater involvement of the Visegrad countries in conflict resolution. This has so far been done mainly through cooperation with EaP countries while the dimension of engagement with de facto states has been neglected.

The primary interest of the EU in post-Soviet de facto states is related to security and its primary role is to support resolution of the protracted conflicts. In this context, engagement can be seen as an insurance policy. Without engaging with the parties to the conflict, the EU would have no leverage in case of re-escalation. This goes the other way too: if the EU’s engagement (such as in trade in Transnistria or civil society projects in Abkhazia) benefit the populations in de facto states, they will be less likely to risk re-starting hostilities. Despite internal divisions among its members, the EU should be interested in containing Russia’s influence in the de facto states. By not engaging, it would simply surrender the post-Soviet de facto states to Russian influence. By empowering local actors (who are often staunchly independent and weary of over-dependence on Russia), it keeps a foothold in the region and sends a signal to Russia that it will not be bullied into accepting the logic of spheres of interest.

In the 1990s, the EU played a relatively small role as a mediator. Consequently, this role was performed by the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), the UN, and OSCE.23 The predominant attitude of the international community at the time was that these unrecognised states are unlikely to persist and that engagement is not just unnecessary, but that it might encourage the entrenchment of separatist elites and contribute to state-building.

The situation changed in 2008. In April of that year, despite warnings and protests from many sides (including Serbia and Russia, but also some EU member states such as Spain and Slovakia), Kosovo declared independence and was recognised by the U.S. and the majority of EU members as well as other countries. In August, there was a re-escalation of the conflict in South Ossetia, which Russia used to intervene militarily in Georgia. Russia ended the remaining Georgian security presence in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and recognised the two entities as independent states, establishing full diplomatic relations. This was a game-changer for the EU. The approach to conflict-resolution that emerged after the recognition of Kosovo in April 2008 and the Russo-Georgian war of August 2008 was based on the idea that engagement with de facto states would de-isolate these entities, foster positive social developments through NGOs and thus reduce their dependence on Russia. The siege mentality in post-Soviet de facto states subsided as there was no imminent military invasion and reincorporation. They also acquired the ability and confidence (especially Abkhazia after Russian recognition) to engage with other states with realistic expectations. Despite paying lip service to the ultimate goal of acquiring international recognition, they seem to be focusing more on short- and medium-term goals, such as state-building, attracting aid and investment, and forging cultural links. There seemed to be genuine willingness for engagement on the side of the de facto states, Abkhazia with its stated multi-vector foreign policy being a prominent example. While this “engagement without recognition”24 approach achieved modest success in civil-society development, it was widely regarded that the EU did too little too late—not providing enough incentive for engagement and missing the short time window when these entities seemed interested in greater engagement before becoming disillusioned and succumbing to Russian integrationist pressures. The EU’s engagement was also constrained by the policies of both the patron (Russia) and parent states—Georgia and Moldova. The EU Monitoring Mission to Georgia (EUMM), the Union’s only “frozen conflict” peacekeeping mission, is denied access to Abkhazia and South Ossetia by Russia and the de facto authorities. While Moldova has allowed Transnistria to export its goods to the European market using Moldovan export certificates,25 Georgia either criminalised or strongly discouraged most types of engagement with Abkhazia and South Ossetia. The high level of integration of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia, and Azerbaijan’s insistence on barring people who have visited Nagorno-Karabakh from entering Azerbaijan, decreased both the need and the possibilities for engagement.

The latest shift in terms of EU engagement with post-Soviet de facto states occurred as a result of Russian military intervention in Ukraine, the annexation of Crimea and support for the rebels in Donbas. The worsening relations between Russia and the EU and U.S. (involving rounds of sanctions and counter-sanctions), has affected EU perceptions and attitudes of Russia as well as the Russia-backed de facto states. But while references to “Europeanisation” and the EU as a “normative actor” in relation to the Eastern Partnership are much rarer, the EU’s approach towards these de facto states has largely remained one of “engagement without recognition.”

Despite the high level of energy dependency of the V4 countries on Russia and disagreements over such important issues as sanctions against and energy cooperation with Russia, the V4 countries have consistently supported the territorial integrity of Moldova, Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Ukraine, refused to recognise the de facto states, and supported the EU’s role in mediation and conflict resolution. It is worth noting, however, that although support for the territorial integrity26 of the parent states is not mutually exclusive with engagement with de facto states, both the EU and the V4 countries have been hesitant, mostly because of parent states’ fears that this would constitute “creeping recognition.” However, recognition never happens automatically or by default,27 and reassuring the parent states or even pressuring them to allow for greater interaction with populations in these territories would open up new possibilities for engagement beyond conflict resolution, humanitarian, and civil society domains.28

Today, engagement is becoming progressively more difficult because of the opposition of parent states, the disillusionment of the de facto authorities, their growing dependence on Russia (in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh on Armenia) and the internal disagreements within the EU. Nevertheless, not all is lost and the EU still has several tools it can use. First, the EU has political tools: experience with mediation and monitoring and a seat at the table29 provide an opportunity for formal engagement with all parties. Second, it has economic tools: the appeal of its common market for those de facto states not yet trading with it (Abkhazia, South Ossetia, and Transnistria) and the economic leverage on ones it is already trading with (Transnistria). Third, the EU has Track II diplomacy and media tools: it is already investing in NGO-led projects in de facto states, supporting the involvement of civil society in conflict resolution and building capacity. Redoubling these efforts and finding ways of better promoting their outcomes could have an important effect on public opinion. Russia could, of course, foil the EU’s plans of deeper engagement. By allowing more engagement, Russia could start losing influence in post-Soviet de facto states, but by actively countering EU engagement (especially if using overt pressure) it would risk alienating parts of the local population in favour of independence and a multi-vector foreign policy.

Challenges and Perspectives

Theoretically, there are four EU policy options towards post-Soviet de facto states: 1) active isolation (embargo and or support for parent re-integration); 2) passive isolation (no engagement); 3) engagement without recognition; 4) recognition. The current stated approach is engagement without recognition, but in terms of implementation falls somewhere between it and passive isolation. Active isolation and recognition are extreme options and would both lead to further destabilisation of the region. There is a quasi-consensus within the European institutions that there is no real alternative to engagement without recognition—the only question is how and to what extent. Keeping in mind that the four conflicts involving post-Soviet de facto states are very different and that a common solution is not possible and a one-size-fits-all approach not suitable, the EU should in the short term continue to support conflict resolution through the Geneva Discussions, Minsk Group and “5+2” talks and continue its monitoring activities under EUMM in Georgia. These conflicts have remained unresolved for more than two decades, they have become increasingly difficult to disentangle, and the solution is not even on the horizon. Yet, this should not preclude the EU from trying since the risks are simply too high to ignore. The situation is currently most unstable in Nagorno-Karabakh, so the EU should urge both sides to continue negotiations and continue working with Russia on deploying even more OSCE observers to the conflict zone (in May, it was agreed to increase the number of observers by seven).

The perspectives for engagement are rather gloomy, both because of the growing dependence and waning interest of the de facto states as well as the lack of agreement among EU member states on a coherent policy. Nevertheless, there is a little room for manoeuvre and the EU should continue direct engagement with civil society to the extent possible. Continued support for democracy, human rights, and freedom of the press should be maintained by the EU, but these should be need-based, locally owned, and not framed as Europeanisation,30 as this is generally seen (in part because of the influence of pro-Russian media) as an attempt to impose Western liberal values on traditionally conservative societies. Environmental initiatives in particular hold much potential due to local needs in this field and tend to be less contentious and politicised than civil rights initiatives.

The EU would also do well to lay out clear criteria and conditions for engagement to make it more transparent and predictable. Drawing the boundaries of engagement would help reassure parent states that engagement will not go too far and amount to “de facto recognition.” It would also help the populations and decision-makers in post-Soviet de facto states understand what they can expect and what is expected of them. Stronger engagement must still be conditional on the approval of parent states, but the EU should invest more effort into convincing them that more rather than less engagement is in their interest31 and persuade them to allow for engagement in areas of trade, infrastructure development and healthcare.32

The V4 countries are well positioned to play a more active role here because of their strategic interest in the EaP, close relationships with parent states, and as examples of the benefits of reform (and potential models) for de facto states.

In the medium term, the EU should consider opening information centres dedicated to de facto states since the media landscape there is dominated by pro-Russian media and most citizens do not have the access, interest, or language skills to read or watch media from EU countries. These information centres should be considered where the prospects for meaningful engagement are greatest, starting with Abkhazia and perhaps followed by Transnistria. This would allow the EU to have a more tangible presence on the ground and to present its accomplishments and opportunities it offers through cooperation. Meanwhile, the EU should work on allowing people living in de facto states greater access to its territory, including for purposes of study and tourism.33 The EU should also advocate for the re-establishment of an impartial international presence in Abkhazia.34

In the long term, the EU, in cooperation with parent states, should look for ways to offer de facto states with the ability and willingness for meaningful engagement, technical assistance to help reconstruct and upgrade civil infrastructure. Another possibility would be to help renovate outdated production facilities, which could contribute to generating jobs, raising the standard of living, and improving environmental quality. In an effort to de-isolate the populations in de facto states, the EU could explore ways to open up channels and give voice to the populations living in these territories. This would prevent complete dependence on Russia, help to further de-isolate these people, give them a sense that the EU cares for them while giving the Union an important opportunity to get direct feedback on how its policies are perceived. It is possible that engagement could benefit Russia, but only if it is conducted unilaterally against the will of parent states and/or would strengthen institutions and resources under Russian control. It is more likely, however, that Russia would attempt to foil the EU engagement, but this could mean paying a price in lost legitimacy amongst the local population. In any case, the EU could consider further engagement with less hesitation, but still be cautious and selective in terms of choosing its goals and methods.

Notes

1 A whole range of roughly analogous terms to “de facto state” exist: unrecognised states, phantom states, quasi-states, para-states, contested states (see: D. Geldenhuys, Contested States in World Politics, Palgrave MacMillan, 2009). Although the term “unrecognised state” may be more widespread and popular (especially outside academia), the majority of scholars studying these entities use the term “de facto states.” The use of “de facto state” is particularly justified in the case of Abkhazia, because it is recognised by four UN members, which technically makes it a partially recognised state, conceptually setting it apart (together with South Ossetia) from Nagorno-Karabakh and Transnistria, whereas using the term “de facto state” avoids this distinction and applies to all of them equally.

2 N. Caspersen, Unrecognized States in the International System, Routledge, 2011.

3 D. Türk, “Recognition of States: A Comment,” European Journal of International Law, vol. 4, no. 1, 1993.

4 S. Fischer, “Not frozen! The unresolved conflicts over Transnistria, Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno-Karabakh in light of the crisis over Ukraine,” SSOAR, 2016, http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/48891.

5 C. King, “The Benefits of Ethnic War: Understanding Eurasia’s Unrecognized States,” World Politics, vol. 53, no. 4, 2001.

6 M. König, “The Effects of the Kosovo Status Negotiations on the Relationship Between Russia and the EU and on the De Facto States in the Post-Soviet Space,” OSCE Yearbook 2007, 2008.

7 N. Melvin, Nagorno-Karabakh: The Not-so-frozen Conflict, Open Democracy Russia, 9 October 2014, www.gab-ibn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/Re13-Nagorno-Karabakh-The-Not-So-Frozen-Conflict.doc.

8 G. Toal, J. O’Loughlin, “Frozen Fragments, Simmering Spaces: The Post-Soviet De Facto States,” in: Questioning Post-Soviet, 2016.

9 P. Rutland, “Frozen conflicts, frozen analysis,” ISA’s 48th Annual Convention, Chicago, 1 March 2007.

10 A good example is Nagorno-Karabakh, which is militarily integrated with Armenia. Armenia and Azerbaijan can both draw on their allies—the former is a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) and hosts the Russian 102nd Military Base in Gyumri and the 3624th Airbase at Erebuni Airport near Yerevan. Azerbaijan is a close ally of Turkey (which has closed the border with Armenia in solidarity), which itself is a NATO member. It is unlikely that the re-escalation of the conflict would involve the broader region, but the conflict dynamics are nevertheless highly unpredictable.

11 See: S. Pegg, De facto States in the International System,” Institute of International Relations, University of British Columbia, 1998; D. Lynch, “Separatist States and Post-Soviet Conflicts,” in: W. Salter, A. Wilson (eds), The Legacy of the Soviet Union, Palgrave MacMillan, 2004.

12 N. Caspersen, A. Herrberg, Engaging Unrecognised States in Conflict Resolution: An Opportunity or Challenge for the EU?, Crisis Management Initiative, 2010.

13 On “engagement without recognition,” see: A. Cooley, L. Mitchell, “Engagement without Recognition: A New Strategy toward Abkhazia and Eurasia’s Unrecognized States,” The Washington Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 4, 2010;, N. Caspersen, A. Herrberg, op. cit.

14 C. King, “The Benefits of Ethnic War: Understanding Eurasia’s Unrecognized States,” World Politics, vol. 53, no. 4, 2001.

15 Freedom House, op. cit.

16 P. Kolstø, “The Sustainability and Future of Unrecognized Quasi-states,” Journal of Peace Research, vol. 43, no. 6, 2006.

17 A. Cooley, L. Mitchell, op. cit.

18 The case of Nagorno-Karabakh is different because most of this de facto state’s foreign policy is conducted through Armenia, making use of and relying on its channels of communication and lobbying, including the Armenian diaspora.

19 C. King, op. cit.

20 N. Caspersen, op. cit.

21 Demographics of ethnic homogeneity often play an important role in how far a de facto state dares to proceed with democratisation. In Nagorno-Karabakh, where an overwhelming majority of the population is ethnically Armenian, this is much less of a problem than in Abkhazia, where barely half—by some accounts, only a good third—of the population is ethnically Abkhaz, prompting the authorities to implement an ethnic democracy that favours the Abkhaz to preserve their culture instead of managing diversity (R. Clogg, “The Politics of Identity in Post-Soviet Abkhazia: Managing Diversity and Unresolved Conflict,” Nationalities Papers, vol. 36, no. 2, 2008). More centralised and authoritarian de facto states tend to simulate pluralism through electoral processes of managed pluralism and fake party-building, although this is more true for Transnistria, which has been described as a hybrid regime (O. Protsyk, “Secession and hybrid regime politics in Transnistria,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 45, no. 1–2, 2012), than for the Caucasian de facto states (H. Blakkisrud, P. Kolstø, “From Secessionist Conflict Toward a Functioning State: Processes of State-and Nation-Building in Transnistria,” Post-Soviet Affairs, vol. 27, no. 2, 2011).

22 J. O’Loughlin, V. Kolossov, G. Toal, op. cit.

23 N. Kereselidze, “The engagement policies of the European Union, Georgia and Russia towards Abkhazia,” Caucasus Survey, vol. 3, no. 3, 2015.

24 It must be stated at this point that “engagement without recognition” does not constitute a clear policy, but more an approach attributed to the former EU Special Representative for the South Caucasus Peter Semneby in 2009. Although various policy documents mention “engagement without recognition,” no EU policy document explicitly defines it. This is understandable since engagement in this context refers to informal contacts between representatives of the EU and of the de facto states.

25 Some have seen this as the capitulation of Moldova and EU to Transnistria and a way of cheapening the Russian imperial operation by providing a lifeline to the Russian-backed regime in Tiraspol. However, extending the EU’s Deep and Comprehensive Trade Agreement (DCFTA) to Transnistria actually supports the territorial integrity of Moldova as well as provides the EU with some economic leverage in this de facto state.

26 The question of recognition in international law is often tied to balancing between the principles of territorial integrity and nations’ right to self-determination. However, due to concerns for the stability of the international system, UN member states are very reluctant to recognise and accept new members, expressing a clear preference for territorial integrity.

27 “As long as a state insists that it does not recognise a territory as independent, and does not take steps that obviously amount to recognition—such as the establishment of formal diplomatic relations through the appointment of an ambassador or the establishment of an embassy—then it does not do so.” See; J. Ker‐Lindsay, “Engagement without recognition: the limits of diplomatic interaction with contested states,” International Affairs, 2015.

28 Respondents in the 2012 public opinion survey of Abkhazians’ attitudes towards the EU carried out by the Centre for Humanitarian Programmes (Abkhazia) in partnership with Conciliation Resources (London) noted that “it is a mystery what Europe fears to lose if it were to take a neutral position. Georgia would not turn away from Europe in any case. But it would make Europe’s influence in the Caucasus as a whole much greater ... .” Some respondents emphasised that if the EU were to change its stance vis-à-vis Georgia’s “territorial integrity,” it could considerably boost its presence in Abkhazia.

29 The EU is a co-chair in the Geneva International Discussions concerning the conflict resolution between Georgia, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, while several of its member states have a seat at the table in other conflict resolution formats, including the Minsk Group (regarding Nagorno-Karabakh) and 5+2 Talks (regarding Transnistria).

30 Europeanisation as an EU conflict-resolution approach focuses on “the consolidation of political reforms and institutions, including respect for human rights and civil liberties, making civil society actors more visible and engaged partners, and creating a political, economic and social environment to which the separatist entities might feel attracted. This is a structural approach to conflict resolution, acting as a stabilising force in the neighbourhood, through the promotion of democracy and changing the conditions within which conflict thrives […] This structural approach, inherited from the enlargement processes, proved very limited once a clear prospect of accession was absent.” L. Simão, “The problematic role of EU democracy promotion in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh,” Communist and Post-Communist Studies, vol. 45, no. 1–2, 2012.

31 It is often thought that political isolation, economic embargos, and counter-recognition strategies will exacerbate the conditions inside de facto states, making it more likely they will eventually give into the pressure or be lured by the relative prosperity of their parent states. However, the empirical evidence does not support this assumption as there are virtually no cases of de facto states giving up their de facto independence (often acquired at great human cost) without the use of force. Gagauzia could be considered in this context since it was reincorporated into Moldova in a peaceful way through institutional arrangement, but the conflict there was not violent and Gagauz leaders were split on the question, eventually deciding in favour of broad autonomy in Moldova.

32 There is a real need for renovating and upgrading roads, bridges, and railways, which tend to be in a very poor, if at all functioning, state as well as improving healthcare facilities in most de facto states (Nagorno-Karabakh being an exception). Positive examples of investment include the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)-funded renovation of the Inguri dam on the Georgian-Abkhaz border, and a positive example of trade is Moldova allowing the use of its export certificates to Transnistria so that they can export their goods.

33 Residents of Nagorno-Karabakh use Armenian passports when traveling abroad and Transnistrian residents often have two or three passports and use Russian, Moldovan, Ukrainian, or even Romanian passports to travel abroad. Residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia face the greatest difficulties as many are denied visas when applying with Russian passports issued in these territories.

34 The UN would be best placed due to its perceived impartiality and experience in the region—the UN Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG) operated between 1993 and 2009. The OSCE is currently internally blocked and the EU is often seen as too partial. It goes without saying that any international presence would have to be agreed to by Russia, which is unlikely in the short-term.

About the Author

Urban Jakša is an Expert Fellow at The Polish Institute of International Affairs.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.