Women in Mediation: Connecting the Local and Global

30 Aug 2017

By Catherine Turner for Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageGeneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)call_made in July 2017.

Key Points

- Women’s representation in mediation remains persistently low despite normative commitments made to increase women’s roles in peace and security.

- There is a gap between the local peacebuilding work of women mediators and the representation of women in high-level peacemaking.

- Focusing exclusively on empowering women at the local level perpetuates a distinction between the “soft” work of peacebuilding conducted by women and the “hard” work of peacemaking that is the preserve of men.

- States and international organisations need to think more strategically about how to forge stronger links among local, national and international mediation practice.

- Greater clarity is needed on the definition of mediation and the distinction between mediation and advocacy.

- It is time to rethink the role and function of mediation in light of changing trends in conflict worldwide.

Introduction

In his December 2016 inauguration speech the newly elected Secretary-General of the United Nations (UN), Antonio Guetterres, indicated that one of the priorities of his term in office would be conflict prevention. He emphasised the need to take more creative approaches to prevent the escalation of conflict, including notably a much stronger emphasis on the use of mediation and creative diplomacy.

This emphasis on conflict prevention was accompanied by a commitment to address a persistent problem in the UN – the need to ensure gender parity. As part of the Sustaining Peace Agenda, Security Council Resolution 2282 (2016) reaffirmed the importance of women’s participation in peace and security, and stressed the importance of increasing women’s leadership and decision-making roles in conflict prevention.

The bringing together of these two priorities, namely an increased role for mediation in international peace and security and a commitment to increasing the participation of women in leadership roles in the UN, presents a good opportunity to consider the role of women in conflict mediation.

However, 17 years after Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) (UNSCR 1325) mandated greater efforts to increase women’s participation in conflict resolution, studies continue to show that women remain under-represented in these processes.1 Greater emphasis now needs to be placed on taking positive action to address the reasons why women remain relatively invisible to international peace and security decision-makers. While there is no short-term fix to the under-representation of women in conflict resolution, steps can be taken to begin to redress the balance.

1. States can take immediate action to include women in their lists of nominees for envoy position through greater political commitment.

High-profile UN mediation most commonly occurs when the Secretary-General appoints an envoy or special representative to offer good offices on his behalf. The role of envoy is a high-level political appointment.

To date, only two women have held the position of envoy with a specific mediation function: Mary Robinson of Ireland was appointed as UN envoy to the Great Lakes region of Africa in 2014, and Hiroute Guebre Sellassie of Ethiopia was appointed envoy for the Sahel in the same year.

The 2015 Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 found that women’s absence in high-level processes cannot be explained by an alleged lack of experience, but rather by a lack of effort to integrate them into formal peace processes.2 The most pressing challenge is therefore to find a way to bridge this gap.

Responsibility for increasing the representation of women in mediation is divided across different UN departments. The appointment of high-level envoys or special representatives of the Secretary- General is overseen by the Department of Political Affairs (DPA). As a political body, DPA works with UN member states to identify a pool of suitable candidates from which envoys may be appointed. As a result, DPA relies on the cooperation and support of member states in its efforts to redress gender imbalance in high-level appointments.

This cooperation among and support of states, which constitute a crucial element of increasing women’s representation, requires that states include suitably qualified women candidates in their lists of nominations for envoy positions. There is inevitably a degree of political complexity to this process. To fulfil this role, women need to demonstrate that they are suitably qualified, and this is done through being involved in high-profile political work; these women therefore may have the required political profile, but lack the mediation experience. Conversely, there are women with significant mediation experience who do not enjoy the same public profile.

States can proactively identify and support suitable women and include more women on lists of nominees, and, equally importantly, they can give their active support to those women who are appointed, and to the Secretary- General in his efforts to increase gender parity. In addition, while the position of envoy is an explicitly political position, other positions in mediation teams – including that of co-mediator – could be made available to experienced women.

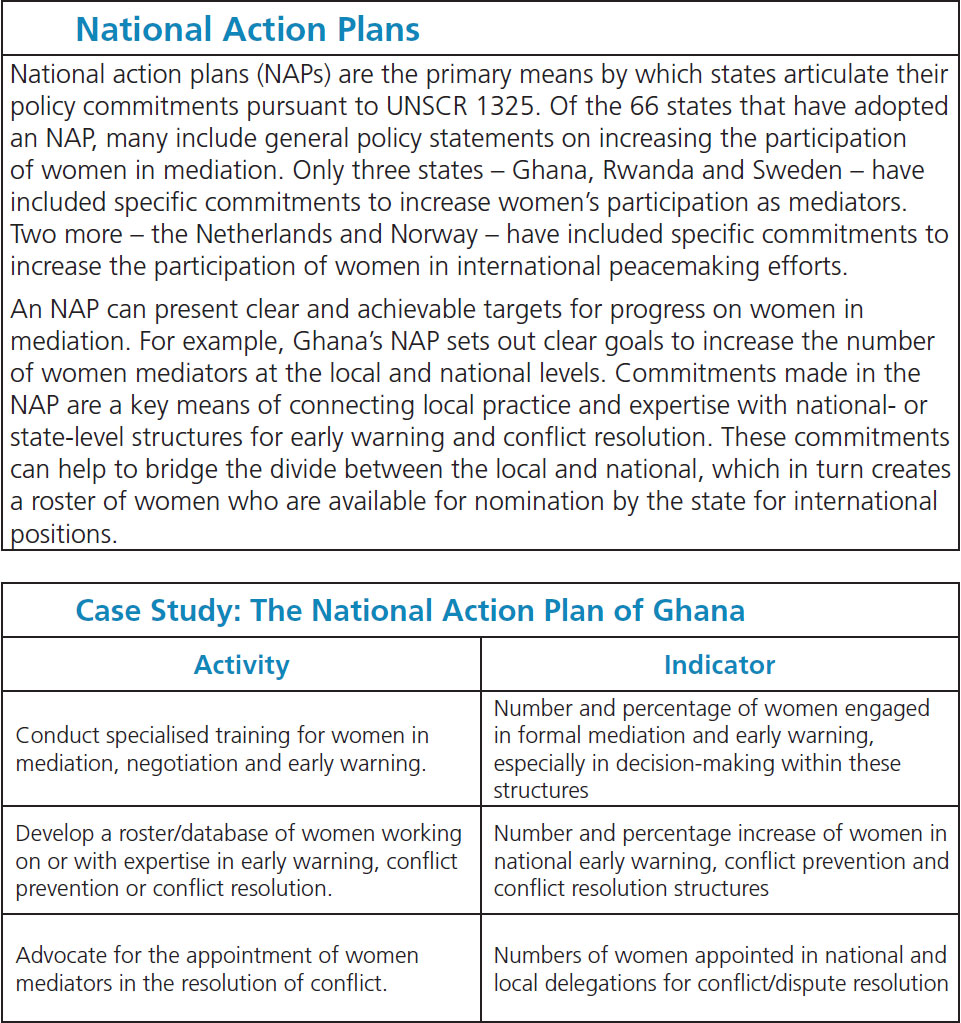

Another way in which states could demonstrate their political commitment to bridging the gap is to make a policy commitment through their national action plans on Resolution 1325 (see Box 1). Policy commitments could address the relative absence of women in these positions to date and make a statement that women are equally qualified to play high-profile roles in mediation. They can also provide resources for better coordination, cooperation, training and capacity-building, as identified below.

2. The international community needs to think strategically about how stronger links could be forged among the local, national and international levels through capacity-building, coordination, and cooperation within and between the UN and states.

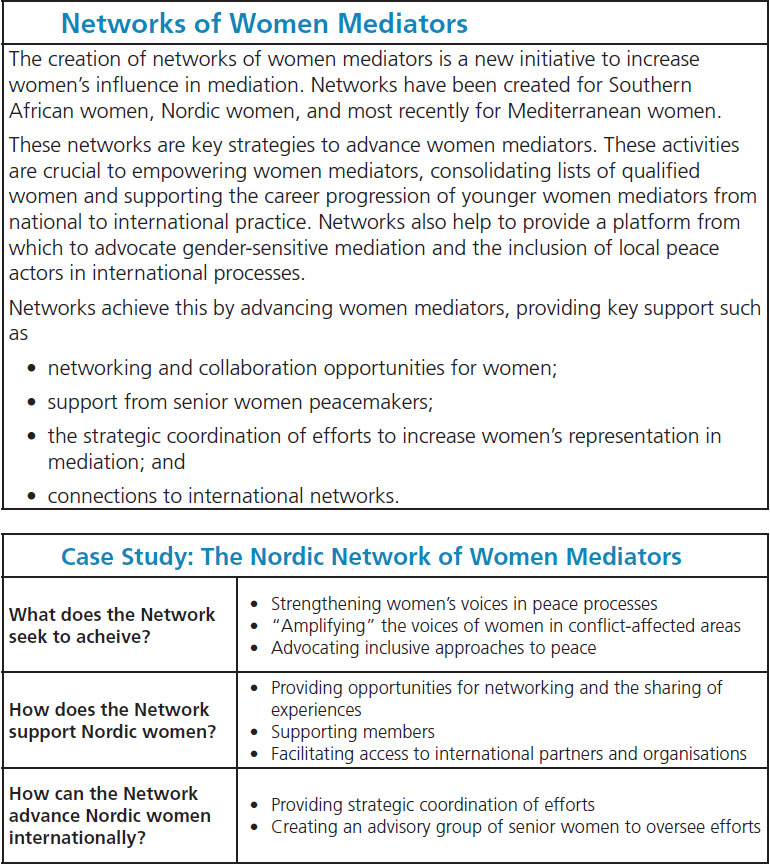

If more women are to be nominated for high-level appointments, it will be necessary to increase the pool of women available for selection. Women mediators are most strongly represented in national jurisdictions, but systemic action to identify them and create career pathways and support for them to move from national to international practice is needed. The local and global can appear to be different worlds. To increase women’s role and visibility as mediators, it is necessary to break down these barriers and to think about how more meaningful connections between these worlds can be forged.

Both DPA and UN Women have processes in place to identify women with the capacity to act as mediators. In addition to the high-level processes overseen by DPA, UN Women is tasked with working with UN member states to further the empowerment of women and support peacebuilding capacity in states. However, there is a gap between the work of UN Women in identifying and cultivating women mediators in local, national and regional contexts and the placing of those women within the DPA system.

This gap means that there has been little success in connecting the efforts of the two organisations to date, despite a shared commitment to improve cooperation.3 The lack of coordination between the different UN entities tasked with peacebuilding roles was highlighted in the 2015 Review of the United Nations Peacebuilding Architecture, which urged the lead departments responsible for peace to “actively explore enhanced ways to work in partnership”.4 Departments need to move away from a system whereby each body focuses on its own specific mandate and adopt a more collaborative approach.

In the case of women in mediation, a more collaborative system would see UN Women help both member states and DPA to identify and recruit experts outside of the traditional UN staffers or political appointees, and seek to promote those with real mediation experience on all tracks in their own countries. This working model is envisaged by the UN in its report on strengthening the role of mediation, in which the need to connect the local and global is highlighted.5 Taking this step would increase the pool of qualified women mediators made available to DPA by expanding the resource base from which appointments are made.

Further, while UN Women and DPA could take steps to improve coordination, states also have a central role to play. As stated above, states can actively identify, promote and nominate women mediators nationally so that DPA has a larger pool to select from. They also play a vital role in creating opportunities to translate skills among local, national and international mediation:6 they can create opportunities for career development at key points and be supportive of broader institutional initiatives to increase the number of women in high-level processes.

States could also cooperate more actively with DPA to provide appropriate training and opportunities. This is not training for the sake of training, but targeted leadership training that addresses the specific barriers faced by women in moving between national and international practice. Some of these barriers operate across the UN system as a whole, because women are less likely to be working in senior positions generally.7

Finally, increasing the visibility of women in Track 1 processes is key to breaking down stereotypes and cultural barriers that limit women mediators, thus publicly acknowledging that the work women do is important.

3. Focusing exclusively on empowering women at the local level perpetuates the distinction between the “soft” peacebuilding work conducted by women and the “hard” work of peacemaking that is the preserve of men.

The previous two recommendations require definite political action and resource mobilisation, and are steps that can be taken immediately, with a view to short- and medium-term improvements in the representation and visibility of women mediators. It is important to ensure that women are adequately prepared to take up high-profile political positions in peace negotiations,8 particularly in political contexts where women are traditionally excluded from the public sphere.

However, these measures are also inherently limited by the system in which they operate. To focus exclusively on this aspect of women’s participation is to overlook women’s expertise and influence across society, the importance of peacebuilding at the community level, and what inclusive peace processes look like.

Women engaged in community work are most commonly described as “peacebuilders” instead of being viewed as having hard skills that they can bring to international peace and security efforts. Policy on and the practice of women’s participation in peace tends to be focused on the question of women’s empowerment rather than as a matter of access or security policy.

However, when viewed as a question of security, the focus shifts towards drawing on women’s skills and mainstreaming them into mediation processes. This opens up the range of positions that women should be expected to fill, moving beyond being participants in inclusive mediation processes to leading these processes. This makes it easier to translate the contribution of women who are active mediators in local conflict into international terms.

Giving greater value and visibility to the role of women in mediation at all levels opens the door to more long-term strategic thinking on how women’s participation in mediation can be used not just to deliver immediate outcomes, but to gradually reshape the model of mediation itself.

We need to move beyond a system where women are simply “added” to the existing structures that focus on power and authority, and undertake a more detailed consideration of what we understand the definition and function of mediation to be. A start would be to break down the distinction between the “soft” work of community peacebuilding and the “hard” work of international peacemaking. This is crucial to both increasing women’s visibility in high-level processes and taking a more realistic, holistic view of what mediation is and where it happens.

4. Greater clarity is needed on the definition of mediation and the distinction between mediation, on the one hand, and advocacy and negotiation, on the other.

There is a significant body of literature that explores the contributions that women make when they participate effectively in mediation processes. However, this focuses primarily on women as participants in the process rather than on women as mediators.9

This distinction is important. It is often assumed that the role of women in mediation is to ensure the proper recognition of women’s rights. Women are active participants in the process, advancing positions and ensuring that women’s interests are addressed, even where they conflict with the positions of the parties. This can be contrasted with the role of the mediator, who acts as an impartial intermediary who seeks to build consensus between the parties. There is a risk that placing too great an emphasis on women’s rights may undermine the willingness of parties to engage. It cannot therefore be assumed that there is a direct link between women acting as mediators and the advancement of women’s interests in mediation.

More research is required to understand the motivations of women mediators and how they understand the mediator role, and to explore the specific category of women as mediators at all levels, and the relationship between mediation and feminist activism to promote women’s interests. This research would help to provide an evidence base to substantiate broader claims about women’s existing skills in this field, identify some of the barriers to the inclusion of women mediators in official Track I processes, and assist with the development of programmes to support women to make the transition from local to national or international mediation.

Mediation is an art – a skill that not everyone possesses. It is therefore important to make best use of those who do possess the skill and to seek to understand how women view the process of mediation. There is an inherent risk that focusing on international experts overlooks those women who have been working at the local and national levels. The career paths for women in mediation should not be restricted to traditional high-profile diplomatic figures or those who have enjoyed international careers, although further examination of the structural reasons that prevent women from achieving such positions is needed.10

Attention needs to be paid to ensuring that the knowledge and skills of women with domestic experience is validated and made visible, that they can define their own role within the process, and they have equal access to opportunities for advancement.11 This will help to empower women mediators at all levels.

5. If women’s contributions as mediators are to be more fully recognised, then a rethinking of the role and function of mediation is required.

The existing system limits the inclusion of women in Track I processes for a number of reasons, many of them practical.12 However, conceptually, the definition of mediation plays a significant role. Re-imagining the role and function of mediation is necessarily a long-term and paradigm-shifting activity, but nevertheless one worth undertaking. While the nature of wars has changed profoundly in the 21st century, the model of mediation has not kept pace.

Calls for inclusive processes have been a response to these changes.13 However, the inclusion approach, while pragmatic and effective, is also limited. The emphasis on using a high-level envoy to mediate maintains a focus on the brokering of agreements between clearly defined warring parties with the aim of restoring the status quo.14 This is at the expense of a broader analysis of the causes of conflict and the response to these causes.

This trend is beginning to be recognised by the UN, as evidenced in the 2012 Guidance for Effective Mediation that highlights the long-term elements of mediation.15 While “peace” may be brokered through official channels, it is “inextricably linked to and often shaped by, the role of civil society and community conflict resolution initiatives”.16 Activism on Women, Peace and Security begins with grass-roots mobilisation, eventually breaking through to high-level and official processes.17

Rather than simply asking how women can be fitted into the existing model of mediation, perhaps it is time to think about what a feminist theory of mediation would look like. Could an emphasis on mediation as inclusive, relationship building and problem solving address some of the current limitations?

Work to ensure greater and more effective participation of women needs to go hand in hand with a robust questioning of the definition of mediation and what it aims to achieve. If the goal of women’s increased participation in peace processes is to achieve a peace that takes account of women’s experiences, then a focus on outcome alone will not be enough. Rather than simply asking what it is we want to achieve, we also need to ask how we are going to get there. It is now time to place a gendered analysis of peace at the centre of what we understand mediation to be and what it seeks to achieve.

Notes

1 UN (United Nations), A Global Study on the Implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, 2016, http://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/UNW-GLOBAL-STUDY-1325-2015%20(1).pdf.

2 Ibid, p.28.

3 DPA (UN Department of Political Affairs), DPA Gender Factsheet, 2016, http://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/GenderFactsheet-US-Format_April%202016.pdf

4 UN (United Nations), The Challenge of Sustaining Peace: Report of the Advisory Group of Experts for the 2015 Review of the United Nations Peacebuilding Architecture, 2015, p.53, http://www.un.org/en/peacebuilding/pdf/150630%20Report%20of%20the %20AGE%20on%20the%202015%20Peacebuilding%20Review%20FINAL.pdf

5 UN (United Nations), Strengthening the Role of Mediation in the Peaceful Settlement of Disputes, Conflict Prevention and Resolution: Report of the Secretary-General, A/66/811 of 25 June 2012, para. 77a, http://peacemaker.un.org/sites/peacemaker.un.org/files/SGReport_StrenghteningtheRoleofMediation_A66811.pdf

6 M. O’Reilly and A. Ó Suilleabháin, “Women in Conflict Mediation: Why It Matters”, International Peace Institute Issue Brief, September 2013, https://www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/ipi_e_pub_women_in_conflict_med.pdf>

7 UN, A Global Study, p.51.

8 See C. Turner and M. McWilliams, “Women’s Effective Participation and the Negotiation of Justice: The Importance of Skills Based Training”, Transitional Justice Institute Research Paper No. 15-03, 2015, https://ssrn.com/abstract=2563690 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2563690

9 See T. Paffenholz et al., Making Women Count – Not Just Counting Women: Assessing Women’s Inclusion and Influence on Peace Agreements, Inclusive Peace and Transition Initiative, 2016, http://www.inclusivepeace.org/sites/default/files/IPTI-UN-Women-Report-Making-Women-Count-60-Pages.pdf

10 UN, A Global Study, p.51.

11 M. Lichtenstein, “Mediation and Feminism: Common Values and Challenges”, Mediation Quarterly, Vol.18(1), 2000, pp.21-22.

12 A. Potter, We the Women: Why Conflict Mediation Is Not Just a Job for Men, Geneva Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, 2005, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/20277/WetheWomen.pdf

13 O. Holt-Ivry et al., “Inclusive Ceasefires: Women, Gender, and a Sustainable End to Violence”, Inclusive Security Issue Brief, March 2017, https://www.inclusivesecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Inclusive-Ceasefires-Women-Gender-and-Sustainable-End-to-Violence.pdf

14 M. Kleiboer, “Understanding Success and Failure of International Mediation”, Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol.40(2), 1996, pp.360-89.

15 UN, Strengthening the Role of Mediation.

16 P. Chang et al., “Women Leading Peace: A Close Examination of Women’s Participation in Peace Processes in Northern Ireland, Guatemala, Kenya and the Phillipines”, Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security, 2016, p.13, https://giwps.georgetown.edu/sites/giwps/files/Women%20Leading%20Peace.pdf

17 Ibid., p.17.

About the Author

Dr Catherine Turner is an associate professor of Law at Durham University and the deputy director of the Durham Global Security Institute.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.