Russian Analytical Digest No 224: Economic Risks and Opportunities For Putin`s Fourth Term

18 Oct 2018

By Emily Ferris and Ben Aris for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The article featured here was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 26 September 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Kremlin.ru external page(CC BY 4.0)call_made

Putin’s Fourth Presidential Term: Looking East for Answers

By Emily Ferris, Royal United Services Institute

Abstract

As President Vladimir Putin begins his fourth term of office, regional administrations are likely to play an increasingly important role in Russia’s foreign and domestic policy decision-making. The underfunded Far East of Russia is likely to become the focus of the authorities’ attention in a bid to attract investment and stimulate the local economy. The Western sanctions will continue to bite and are likely to be periodically extended and expanded in the coming months, obliging Russia to approach non-Western countries, such as China and Japan for foreign investment in the Far East, although diplomatic disagreements will ensure this investment remains restricted.

Introduction

When Vladimir Putin resumed the presidency in March 2018 for his fourth term, discussions over the likely course of Russian domestic and foreign politics focused disproportionately on him and his ever-diminishing circle of trusted advisors. Examining Putin is important, but this approach overlooks other powerful political apparatuses in Russia that have a strong influence on domestic affairs, and which can also affect Russia’s foreign policy decision-making.

Russia’s economy is only sluggishly improving, following the oil price fluctuations and concomitant imposition of Western sanctions in 2014, which were introduced in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its military intervention in eastern Ukraine. The World Bank has forecast that Russia’s economy will grow by just 1.5–1.8% in 2018–2020, which will be largely dependent on oil prices that have remained depressed—Russia relies on oil for almost half of its annual revenues.

Investing in the East

The authorities are aware that to stimulate the economy and prevent a downturn in real wages, Russia will have to encourage foreign investment. However, the sanctions—and the likely prospect of further US sanctions as the Mueller inquiry continues—have restricted Russia’s access to European capital markets and technology, particularly in the oil and gas sector, and reduced the pool of willing investors. Russia has already begun to turn to non-Western partners to account for this trade deficit, and one of the main priorities will be attracting foreign investment to the underfunded Far East, where wages are low and local infrastructure is poor.

Many of Russia’s untapped natural resources are located in the Far Eastern regions, but the territory is underfunded, sparsely populated and in significant debt to Moscow. When Putin was re-elected to the presidency in 2012, he issued the so-called May Decrees, a package of laws stipulating—among others—that the regions must raise local salaries. Attempts to follow this resulted in spiralling debts to Moscow, and in November 2017 several regions requested financial assistance from the capital. However, while the Russian government is in principle open to foreign investment, a 2008 Russian law stipulates a list of more than 40 sectors that the authorities have designated as ‘strategic’—sectors of significant economic importance that tend to receive prioritised government subsidies and resources. These sectors include defence, the oil and gas industry, and natural resources, such as mining. Foreign investment in these sectors is often highly restricted and projects in this area tend to attract the attention of powerful local business figures—foreign companies who find themselves embroiled in business disputes with these entities rarely prevail.

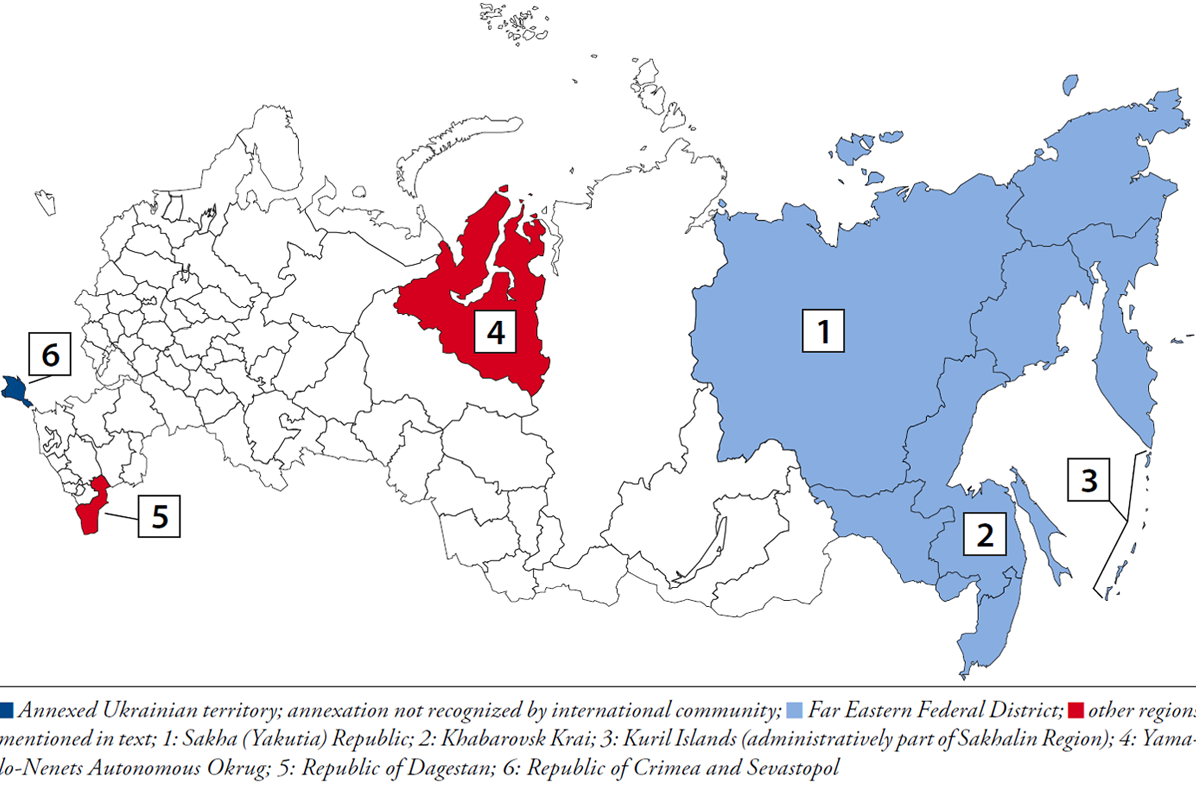

Encouraging investment to improve local infrastructure, create jobs and raise wages is also a political move. It is significant that in the March 2018 presidential elections fewer people voted for Putin in the Far Eastern region of Yakutia than in 2012—64% compared with 69%. In the neighbouring Khabarovsk region, votes were similarly low, at 65%. Demonstrations in the Far East over environmental pollution from factory waste, spats with local companies over delayed wages and protests against corruption are small but growing, and the authorities are keen to placate blue collars workers in particular, because they are historically a key support group for the incumbent United Russia party.

Regional Governors: Reshuffling the Deck

Regional administrations governing the Far East are likely to become increasingly prominent and influential in the coming years, as Russia attempts to encourage Japanese and Chinese investment there. While Moscow is the nexus of Russia’s political power, Russia’s regional administrations handle most day-to-day matters, particularly business. Good relations with governors and the administration they control are often the key to successful investment for both foreign and local companies. Governors can mediate disputes between companies and local Russian firms, assist in hiring local workers and facilitate bureaucratic licensing procedures.

Over the past three years, Putin has reshuffled many of these governors—some were promoted beyond the regional administration, others were naturally reaching retirement age, and some had courted public scandal or failed to economically stimulate their region. Some reshuffles have a clear security intent; for example, in November 2017 Vladimir Vaseylov was installed as the governor of the volatile southern region of Dagestan. Vaselyov is a long-serving member of Putin’s United Russia party and a Muscovite—his appointment was intended to break up local clan networks and promote loyalty to the central government.

The Kremlin measures governors’ performance based on an annual review. Those at the upper end of the scale tend to be rewarded and those at the lower end dismissed. In May 2018, Yegor Borisov, governor of the Far Eastern Yakutia region, was dismissed—Borisov had been ranked in 63rd place out of 85 governors and was removed just before the results were published, owing to his involvement in a long-standing corruption scandal within his regional administration that involved skimming funds from a local investment programme. Borisov’s dismissal could also have been linked to his failure to secure sufficient votes for Putin during the elections.

Many of the governors now climbing the ranks of the administration are younger, replacing the gentrified Soviet-style leadership, who tended to remain in office long past retirement age. Some governors have the traditional background in the security services, but others increasingly hail from the private sector, and are selected for their business acumen. Dmitry Kobylkin was appointed Minister for Natural Resources in May 2018, a position that oversees Russia’s oil and gas strategy. Kobylkin had spent many years in the oil and gas industry—his appointment was a promotion following the successful governorship of Yamal-Nenets, a large Arctic region that exhibited major economic growth thanks to the discovery and development of oil and gas fields on the Yamal Peninsula.

Several major positions relating to the Far East have also recently been reshuffled. The Minister for the Development of the Far East, a relatively new ministry only established in 2012, was taken up by Alexander Kozlov in May 2018. Putin also has his own Presidential Envoy to the Far East, Yuriy Trutnev, a highly influential figure and former Minister for Natural Resources (2004–2012), who assumed his post in 2013. Trutnev, who most recently travelled to China on a working visit to discuss investment prospects in August, facilitates investment discussions with Chinese investors—a Chinese company called COFCO Coca-Cola announced in late August 2018 that it was considering investing in drinking water production in Russia’s Far East and parts of Siberia.

The Russian government also established the Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) in 2015, an annual affair held in September on Vladivostok’s Russkiy Island, with the aim of attracting foreign investment. The Russian authorities are particularly keen to promote the Far East’s Special Economic Zones (SEZs)—areas that allow tax exemptions or very low tax rates in exchange for significant investments in the local economy. Representatives from China, Japan and South Korea routinely attend the EEF. At the 2017 event, the Russian authorities announced that 217 commercial deals were signed, worth USD44bn. Investment contracts worth more than USD60bn are likely to be signed at this year’s forum, with dignitaries, such as Chinese President Xi Jinping, scheduled to be in attendance.

Diplomatic Deadlocks

However, there are several serious obstacles to Chinese and Japanese investment in both the Far East and other parts of Russia.

While China has longstanding business relationships in Russia at a local level that predate the fall of the Soviet Union, there is still mutual mistrust on both sides. Although Russia and China occasionally appear to be diplomatically in sync—they tend to support each other’s votes on the UN Security Council—Russia has been rankled by China’s Belt and Road initiative that broadly bypasses Russia and uses countries like Ukraine as a cargo transit country to Europe. Russia is already China’s largest supplier of crude oil, but is reluctant to be pigeonholed as a commodity supplier. The two countries have also clashed over China’s enduring influence in Central Asia’s gas industry. As a result, Chinese investment in the Far East has been piecemeal and relatively small-scale, despite routine investment forums and bilateral meetings.

Russia’s diplomatic relationship with Japan is also complicated. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also attends the Eastern Economic Forum every year, and frequently meets with Putin. Japan and Russia share mutual security concerns, such as North Korea’s nuclear programme, but a long-standing disagreement on the status of disputed islands is preventing deeper cooperation. Russia claims the Kuril Islands, known in Japan as the Northern Territories, as its own, but many preliminary economic agreements drawn up with Japan hinge on some recognition of the territory as Japanese. Japan has proposed the return of some of the smaller islets in exchange for further investments, but Russia is unlikely to agree to this. Moreover, Russia’s militarisation of the Kuril Islands is a further concern for Japan. Russia has deployed new missile defence systems and has plans in the pipeline to construct a naval base there. In turn, Russia is concerned that Japanese ownership of the islands could provide a platform for a future US military base on the Kuril Islands, which Russia would consider a serious security issue.

Further complicating the mix, Japan has fallen in line with the US and EU’s approach to Russia and, in 2014, introduced its own sanctions on Russia, which are linked to its annexation of Crimea and military activities in eastern Ukraine. Japanese investors are very cautious of falling afoul of them and are also wary of investing in large-scale energy projects in Russia that could become sanctioned by the US in future.

Notwithstanding these political obstacles, the authorities will continue to prioritise the development of the Far East and providing resources to the institutions that govern it. Although Moscow is technically the hub of Russia’s political institutions, the Far East and the ministries responsible for it will become the focus of Russia’s strategy towards East Asia in the coming years.

Figure 1: Map of Subjects of the Russian Federation Highlighting Regions Mentioned in Text

About the Author

Emily Ferris is a Research Fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a defence and security think-tank based in London. Her research focuses on Russian foreign and domestic politics, with a particular interest in Russian organised crime. She has previously written for Foreign Affairs, Forbes and the Moscow Times.

Putin 4.0: State-Led Reforms to Remake Russia’s Hybrid Economic Model

By Ben Aris, business new europe

Abstract

Russia’s president Vladimir Putin has just started his last term in office, which could be the hardest of his four terms in office. The petro-funded economic model is exhausted and the Kremlin is trying to create a new model, based on investment and innovation. However, while the population also want change, they want gradual change. The result is a hybrid model of introducing competition into the economy, but leaving the state in control of the main levers of power.

After being swept back to power in the March presidential elections, Russian President Vladimir Putin has started his last term in office and has his eye on his legacy. The constitution limits a Russian president to two consecutive terms in office, which will expire in 2024 after the rules were changed to extend terms from four years to six. At this point, most commentators are expecting him to stand down after 24 years in the job.

And the job has changed dramatically in that time. When he took office in 2000, he was presiding over a wrecked economy that was recovering from a major economic meltdown and was being looted by the oligarchs that had grown powerful in the Yeltsin-era. The devaluation of the ruble in 1998, when it lost three quarters of its value, gave the economy the first shot in the arm, and the relentlessly rising oil prices—oil prices rose from $10 in his first term to $150 by the time he took his hiatus as prime minister in 2008—fuelled an economic boom that saw the economy double in size.

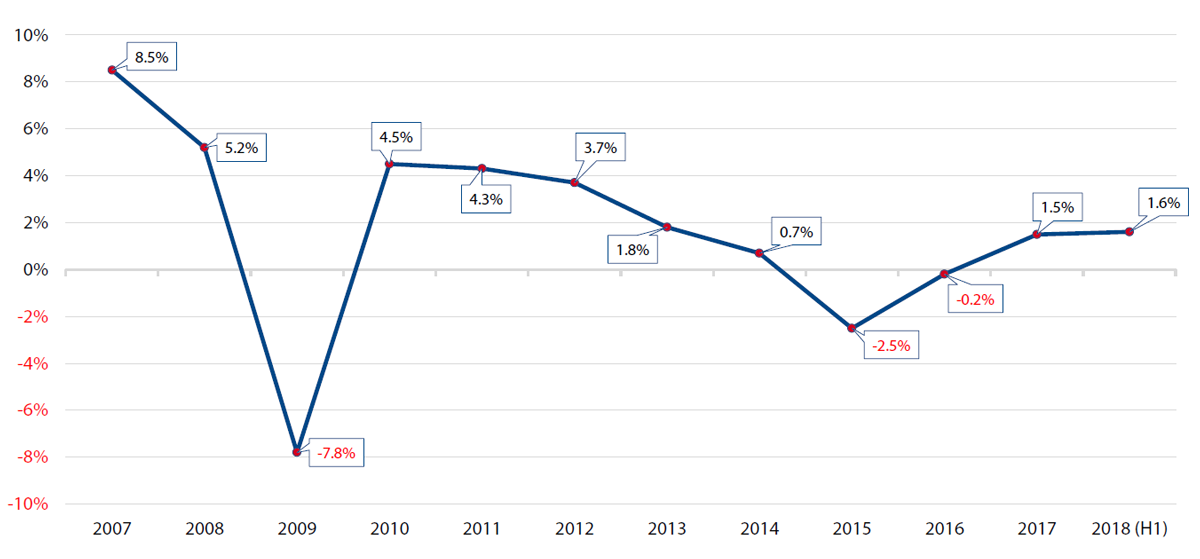

However, the petro-dollar driven growth model was fully exhausted by 2011, by when growth had started to slow and by 2013 growth had fallen to zero, well before the Kremlin clashed with the West over Ukraine and despite the fact that oil was still over $100 a barrel.

Commentators and critics have long complained about the lack of deep structural reforms that Russia needs to flourish and this became patently obvious to even Putin in 2013. But his political agenda has not allowed him the freedom to concentrate on the economy. Already in 2012, Putin had decided a clash with the West was inevitable and that was the year he passed the now infamous “foreign agent” NGO law that stigmatizes any NGO receiving foreign funds, as well as launching a multi-trillion ruble modernization of the Russian military. Liberals in government, most noticeably former Finance Minister and now head of the Audit Chamber, Alexei Kudrin, were sacrificed along with Russia’s new-found prosperity, as all spare resources were funnelled into military spending. Incomes that had been rising by 10% a year for a decade began to fall in 2015 as the economy spluttered and stalled.

In parallel, political tensions with the West escalated to reach a crescendo in May 2014, when Russia annexed Crimea and sent its military into the Donbas region of western Ukraine. What followed was a two year long “silent crisis” during which incomes fell, the banking sector teetered and major state-owned enterprises (SOE) struggled to meet their debt obligations. Russia’s economy came close to a real crisis in 2016, when then Finance Minister Andrei Siluanov had a external pageRUB2 trillion hole in the budgetcall_made, a hole that was only filled at the last minute by the “privatization” of a 19% stake in state-owned oil major Rosneft, bought by Swiss-based trader Glencore and Qatar Investment Authority (QIA) for $12.2bn. The deal later turned out to be a loan in disguise and part of the stake was subsequently sold to CEFC, who has since reneged on the deal.

But it doesn’t matter any more. The rise in the price of oil over the last year means the Russian budget is back in profit. The Ministry of Economy was forecasting a modest 1.5% of GDP deficit, but at the time of writing the budget was already in surplus and could end the year with as much as 2% of GDP surplus. The three-year budget plan assumes average oil prices of $40. However, over the first part of the year, oil was averaging over $60 per barrel and that rose to $75 over the summer months. In the meantime, the breakeven price of oil for the budget has fallen from a peak of $115 in 2008 to $53 now, according to Renaissance Capital’s calculations. The financial pressure is off the government.

However, the fundamental problem of a petro-based economic growth model has not been solved. The Ministry of Economy’s forecast for growth in 2018 was a mere 2%—a goal that has been cut twice this year to the current 1.8%, as the US has ratcheted up sanction threats. For an emerging market that rate of growth represents stagnation, as the rest of the world will grow significantly faster in the coming years, which means Russia’s economy will inexorably fall behind its peers and rivals unless it grasps the reform nettle.

And Putin has a plan. Putin unveiled a very ambitious spending plan during his external pagestate of the nation speechcall_made on March 1. The President wants productivity growth to accelerate to 5% per year (since 2009, the average growth was only 1%) during next decade, the share of SMEs in GDP to go up to 40% (from current level of 20%), the number of people employed in SMEs to go up from 19mn to 25mn people, and to halve the number of people living below the poverty line (currently 13.8% of the population or 20mn people).

In addition, he proposed a external pageRUB8 trillion spending extravaganzacall_made over the next six years to be spent on the social sphere and infrastructure to “transform” the Russian economy and to create a new economic model, based on technology and innovation. Although it is neither clear where the funding for this approximately RUB2 trillion a year of extra spending will come from, nor are the details of the national spending projects on the table, Putin has already bitten the bullet on two painful changes.

In the midst of the World Cup in July, when the population was distracted by the Russian national team’s heroic performance, the government announced two radical reforms: retirement ages were increased from the Soviet-era 55 years for women and 60 years for men to 63 and 65 respectively by 2028; and VAT was hiked from 18% to 20%.

These are radical changes, as the early retirement ages are seen as a basic perk: few pensioners actually stop working when they “retire” and so a pension is a subsidy that dramatically improves a Russian’s life and most eagerly look forward to the extra income. On taking office in 2000, the first thing Putin did was introduce a flat rate 13% income tax on the population that has been sacrosanct ever since. The VAT hike is the first time the government has directly increased the tax burden on the population since Putin has been in office. Both reforms have been extremely unpopular. Putin’s personal rating tanked from over 80% into the 40s as a result.

But the reforms show Putin’s commitment to change. He made a standard political decision to push through painful, but badly needed reforms in the honeymoon period after re-election that gives him the maximum possible time in the political cycle to recover from the blow. And neither reform could be dodged given Russia’s demographics and the need to fund the RUB8 trillion of new spending; one pensioner used to be supported by the social taxes of two workers, but that ratio has already fallen to close to 1:1, thanks to the demographic dip from the 90s. Putin has calculated he has enough political capital to afford to spend some on making these changes. And two months after the announcement in a rare TV address Putin softened the terms of the reform, reducing the retirement age for women to 60 from the originally mooted 63, and introducing exemptions for women with more than 3 children to sweeten the medicine (Putin also won 61% of the female vote in the March elections, so this is a core constituency for him.)

More generally Putin has reorganized the government to try and reduce corruption, increase accountability and boost efficiency. One of the positive effects of the silent crisis and the RUB2 trillion budget hole problem of 2016 is that it has promoted a revolution in the Russian tax service. The taxman’s IT system has been totally overhauled and put online, so that one Russian cosmonaut has even paid his taxes from space, while serving on the International Space Station. Next up are the regional governments that have hired external pageIBS IT Servicescall_made, Russia’s software developer, who are putting regional government’s finances into the cloud, thus enabling just-in-time payments that vastly improve their cash management. There has also been a crackdown on corruption that has seen several regional governors arrested and even the sitting minister of Economics, Alexey Ulyukayev, was arrested and jailed for taking a bribe (although this case also contained a strong element of power games, as he had offended Rosneft’s CEO, Igor Sechin). The upshot of this tax revolution has been that tax collections were up by some 40% last year.

The next step is to improve the spending of tax revenues. These changes were made after Putin’s reelection and started with the appointment of Kudrin as head of the Russian Audit Chamber. Previously, this body played little role in Russia’s political life and was a retirement home for ex-prime ministers. However, the chamber has been growing in prominence. Kudrin takes over from external pageTatiana Golikovacall_made, who began a revolution at the chamber to make it an instrument of accountability for regional government spending. When she finally left the chamber earlier this year, she burst into tears at the lectern during her goodbye speech, but claimed to have prevented RUB46bn of wasteful spending in the last year alone. A close ally of Kudrin’s, she received a major promotion in the external pagegovernment reshuffle following Putin’s electioncall_made. She was appointed straight to the post of Deputy Prime Minister responsible for the social sphere, close to the top of the hierarchy, where she will have responsibility for overseeing a large part of the RUB8 trillion of spending.

Pundits were disappointed with Kudrin’s appointment to the Audit Chamber job, because they hoped that he would be given a top job in the government or a very senior post in the presidential administration (that actually runs the country). However, it appears the intention is to make the Audit Chamber into what its name suggests.

The Audit Chamber will be given carte blanche to inspect regional spending, suggesting that the Kremlin sees the institution becoming a key watchdog under Kudrin and he has called for the Chamber’s mandate to be expanded to include the power to audit the Central Bank of Russia (CBR).

Kudrin laid out the four main objectives for the Audit Chamber as: curbing corruption, tying Russia’s strategic development goals to the actual budget, enhancing the methods of budgetary control, and informing the public on the realisation of national strategic goals. “The question is not, whether we spend the money in accordance with the procedures, but whether the spending is getting us closer to the national strategic goals,” Kudrin said in April. This results-based way of thinking would be a pretty new way of thinking for the plodding Russian government.

The final piece in the puzzle is supervising spending on ad hoc really big projects, specifically infrastructure investments. The bridge connecting Russia’s mainland to the Crimean peninsula cost upwards of $4bn and clearly has political, as well as economic, value, but these types of projects usually become feeding frenzies for corruption apparatchiks.

At the end of May, external pagePutin appointed Igor Shuvalov as the head of the state development bank Vnesheconombank (VEB)call_made, which has been responsible for big projects in the past. Shuvalov is another heavyweight bureaucrat, who has been Putin’s economic deputy since 2008, and later first deputy Prime Minister, and is formally the third most powerful person in Russia. Just like Kudrin, Shuvalov is a long-time Putin’s ally who has proven his efficiency in office. VEB will be another agent that spends vast amounts of state cash on economic development projects.

VEB’s main job will be to oversee a external pagenew RUB3 trillion ($50bn) fund for infrastructure investmentcall_made that is supposed to be established in 2019, the Finance Minister Anton Siluanov told delegates at the St Petersburg Economic Forum this year. The fund would function until 2024 and would be directly tied to the latest May Decree of President Vladimir Putin, which, among other ambitious goals, external pagelays out a plan for massive infrastructure spendingcall_made. “This decision practically stems from the president’s decree and will be one of the sources of securing high economic growth rates,” Siluanov said in May, adding that the fund would be replenished with borrowed funds.

VEB’s control over gigantic infrastructure investment formalises the system of using state sponsored oligarchs, or external pagestoligarchscall_made, that Putin has adopted until now. That officials and businessmen will steal from the state is a given, but by increasingly limiting access to big projects to a shrinking circle of businessmen, Putin has secured personal control over Russia’s biggest state sponsored projects, such as the construction of the Kerch bridge to Crimea or the Power of Siberia gas pipeline connecting Russia and China—the contracts for both were given to the two main stoligarchs, Gennady Timchenko and Arkady Rotenberg. These two men were dubbed the “kings of state contracts” by Russian daily Vedomosti, as they have won more state contracts than anyone else in 2017 and have been involved in every major building project over many years, from the Sochi Olympics to the World Cup and beyond.

By handing over infrastructural investment projects to Shuvalov and VEB, Putin is effectively delegating to the stoligarch system and expanding it. It is a hybrid system in which Putin maintains personal control over the biggest state spending projects, whereas the more general spending on the population and businesses at large has been delegated to Kudrin and his team. Shuvalov is a personal ally of Putin, whereas both Golikova and Siluanov used to work for Kudrin, who leads the liberal economics block in the Kremlin.

In general, Russia’s economic model is a hybrid in which the state likes to stay in charge, but in order to win the benefits of market-based competition, it sets up two large state-owned entities to compete against each other. The economy is marked by these pairs: Sberbank vs VTB bank in the financial sector; Rosneft and its gas subsidiaries vs Gazprom & and its oil subsidiary Gazprom Neft in hydrocarbons; and Irkut and Sukhoi in aviation, to name three of the most obvious. However, large sections of the economy, such as retail, agriculture and technology, in which turnover is high, but margins are low, have been left to the liberal block to manage and are largely free and subject to market forces.

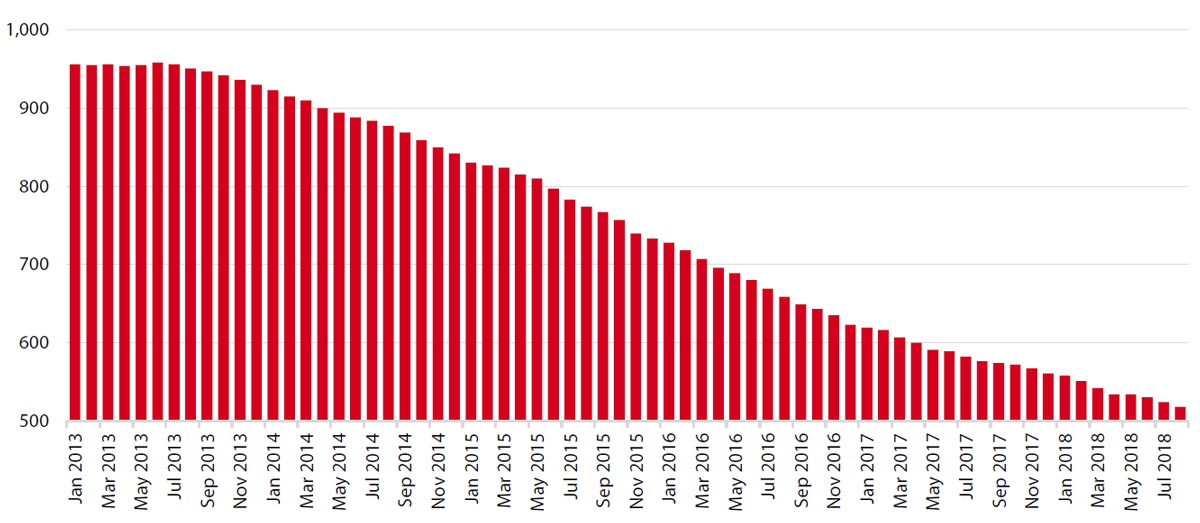

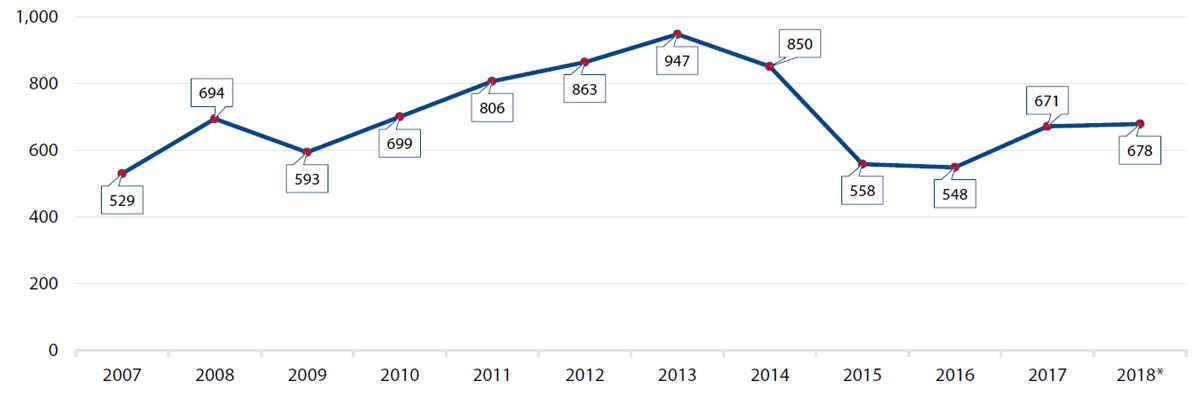

Another of Kudrin’s former employees is CBR governor Elvira Nabiullina, who has been put in charge of cleaning up the banking sector. Of all the reforms, this is by far the most advanced. Nabiullina has been closing 100 banks a year since she took the job in 2013 and has halved the number of banks since then to 518, as of August this year (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Russia: Number of Banks (EOP)

Nabiullina is also a former personal economic advisor to Putin from the presidential administration, but Putin has not made Turkish president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s mistake and has left the CBR’s independence intact. He trusted Nabiullina’s call to impose an emergence rate hike of 10% to 17% in the midst of the 2014 ruble meltdown, an incredibly painful decision, but one that preserved Russia’s hard currency reserves, whereas Erdogan has pointedly refused to allow the same, even though this decision was badly needed in Turkey this summer.

Nabiullina is coming to the end of her clean up operation, as the informal goal is to have some 300 banks— similar to Germany’s system—which will be achieved in the next two years. And the process is becoming more painful as that goal is approached. Following the “wild cat” banking days of the ‘90s, Russia has been badly overbanked, with most banks acting either as glorified treasury operations for large companies or outright money laundering scams fuelling capital flight.

In April 2017, the newly created Russian Analytical Credit Rating Agency (external pageARCAcall_made)—a domestic rating agency, which is another new control institution like the Audit Chamber, but for banking—pulled its AAA rating for several large commercial banks, including external pagePromsvyazbank (PSB)call_made and external pageFinancial Corporation Otkritiecall_made.

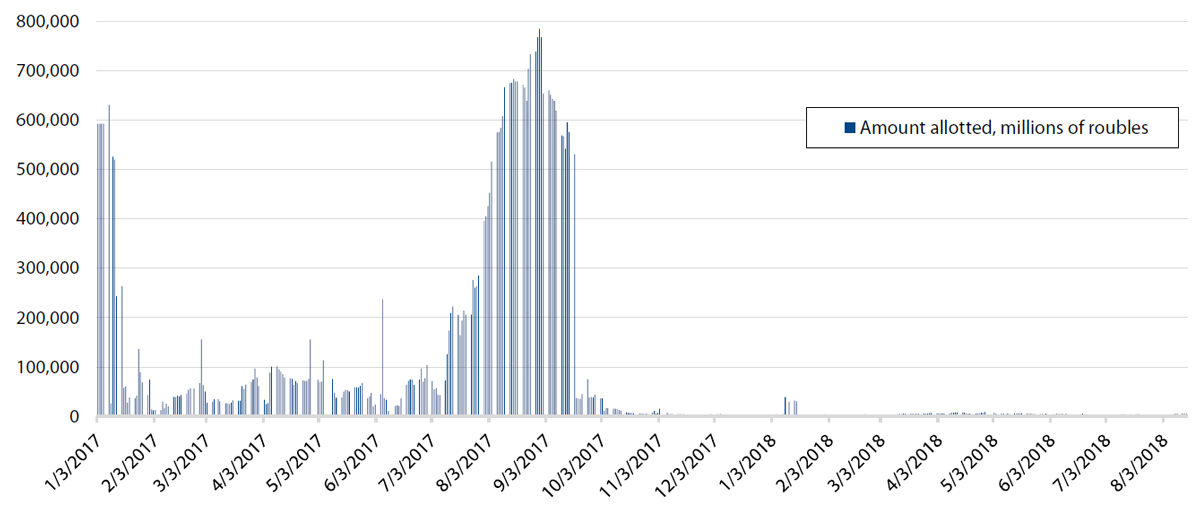

This automatically means SOEs are no longer allowed to keep money at these banks, starting a run on accounts that led to a mini-banking crisis in September. Also, in April, anticipating the crisis, the CBR had set up a new Banking Sector Consolidation Fund (BSCF). Previously, if a bank went bust, then depositors were compensated by the Deposit Insurance Agency (DIA), but the size of these commercial banks were simply too big for the government to just bail them out. The scale of the crisis was clearly visible in the repo volumes, as banks rushed to the CBR to borrow cash against their bond holdings until the CBR took the struggling banks over and the subsequent calm in the sector would be restored (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Russia Repo Volumes (mn RUB)

Instead, they were taken over by the BSCF and allowed to stay open, thus avoiding the need for an expensive bail out. As it was they still needed trillions of rubles in support, but in theory the CBR can recoup this money by selling the banks again.

While the September 2017 mini-bank crisis looked bad from the outside, it transpired that all four of external pagethe so-called Garden Ring bankscall_made were owned by the same group of shareholders and had bought pension funds, which they used to pump up their balance sheets. The Garden Ring banks were a disaster waiting to happen once the pension fund market stopped growing.

In addition to closing banks, Nabiullina has been introducing better and closer supervision for the 25-odd “systemically important” banks, but the main gain has been to reduce the number of banks to a number that the CBR can effectively supervise.

These are not the radical reforms outside observers would like to see, but the pace is what the Russian people would prefer. external pagePolls showedcall_made in 2018 that the majority of Russians want change, but they want gradual change. Russia is caught in a external pagemiddle-income trapcall_made, whereby the population is more worried about losing the substantial gains in their quality of life made over the last 17 years, than they are about seeing fresh advances. Putin has tailored his reforms to meet these concerns—the watering down of the pension reforms is a classic example— but the danger is if reforms are not radical enough that Russia will slide backwards behind the rest of the world and stagnate.

Russia’s economy is now stable and growing again and, indeed, has scored several successes. Inflation and unemployment are currently at record post-Soviet lows of 3% and 4.7%, respectively. Overnight interest rates are at a high of 7.25%, but have been coming down. Growth is a lacklustre 1.8% and industrial production was a similarly uninspiring 3.9% in July, but the economy is recovering. However, with gross international reserves (GIR) standing at a massive $460bn, or 17 months of import cover, and external debt a mere 15% of GDP—one of the lowest levels in the world—Russia’s economy has a giant cushion, with lots of wiggle room. The wildcard hanging over the economy’s outlook for the rest of Putin’s last term in office is the severity of future US sanctions. The first round of sanctions imposed in 2014, following the annexation of Crimea, were largely symbolic—a list of visa bans for a few generals and government officials involved in the operation—, but nevertheless caused a big sell off of Russian assets.

However, since then, the sanctions have become increasingly more painful and have increasingly targeted Russian companies and finances. So far this year, there have been four sanctions events: the so-called Kremlin report in February; the external pageApril 6 round of sanctionscall_made that targeted external pageRusalcall_made owner and Kremlin insider, Oleg Deripaska, which caused chaos on the metal markets; the Defending Elections from Threats by Establishing Redlines Act (DETER) that are again largely symbolic; and the most recent Defending American Security Against Kremlin Aggression Act (external pageDASKAAcall_made) that, if adopted this autumn, could do real damage to Russia’s long-term growth prospects.

Unlike the previous sanctions, the DASKAA targets Russian sovereign bonds, and Ministry of Finance treasury bonds, in particular OFZ bonds, which are the workhorse bond used by the Ministry of Finance to finance budget spending. Pundits think it is unlikely that the US Treasury Department (USTD) will go through with the threat to sanction the owners of these bonds, as they are so widely held internationally. International investors owned 34% of the outstanding OFZ at the start of this year, but just the threat of sanctions has seen a sell-off and foreign investors now own only 27%, or some $30bn, of these bonds.

MinFin was intending to double borrowing using OFZs to RUB2.5 trillion next year, in order to fund the Putin spending plan, but if ownership of these bonds is sanctioned by the US, not only would this funding be unavailable, but MinFin said, at the start of September, that it may buy these bonds back, and has RUB3 trillion ($44bn) on hand just in case. Because of Russia’s extremely strong public finances, it could absorb the shock of a ban on OFZ ownership and hence the sanctions would fail, but they would also derail Putin’s May Decree plan for transforming the Russian economy. What that would mean for Russia’s long-term development is not clear. Putin has very successfully played the “fortress Russia” card, in response to the US’s sanction attacks on Russia. Indeed, the landslide victory he won in March—Putin gained some 10mn more votes in March, than in the previous elections—was partly a result of Russians rallying around their leader’s flag, in the face of the hysteria in the West that followed the poisoning of the ex-spy Sergei Skripal.

If the sanctions regime is designed to force the Kremlin to change its behaviour, as is the nominal goal, then it is failing; the practical upshot of sanctions has been to cement Putin’s support and embolden his push back.

And the increasingly combative nature of the US president, Donald Trump’s administration is also starting to have noticeable repercussions in the West. As Business New Europe (bne) wrote in a recent op-ed, the craziness of the Trump administration is external pagethreatening the post-WWII security world ordercall_made. German Chancellor, Angela Merkel has called for a settlement with Russia and the new foreign minister, Heiko Maas is calling for a new Ostpolitik to deal with the Russia problem. How far these changes will go remains an unanswered question, but clearly they create opportunities for Putin, who is said to lack a strategy, but is always a consummate tactician.

The bottom line for the Kremlin is that, with the annexation of Crimea, it resigned itself to long-term confrontation with the West. The goal is not to get the sanctions removed, as like the Jackson-Vanik sanctions, it expects to be under sanctions for decades, but instead to get them watered down to a level that would allow the Kremlin to continue with its long-term transformation plans and continued access to the international capital markets. To sanction Russia’s sovereign bonds would be seen by the Kremlin as an economic act of war, which would make the future even more unpredictable.

About the Author

Ben Aris is the founder and editor-in-chief of business new europe (bne), the leading English-language publication covering business, economics, finance and politics of the 30 countries of the former Soviet Union, Central and Southeastern Europe and Eurasia.

Statistics

Real Economy

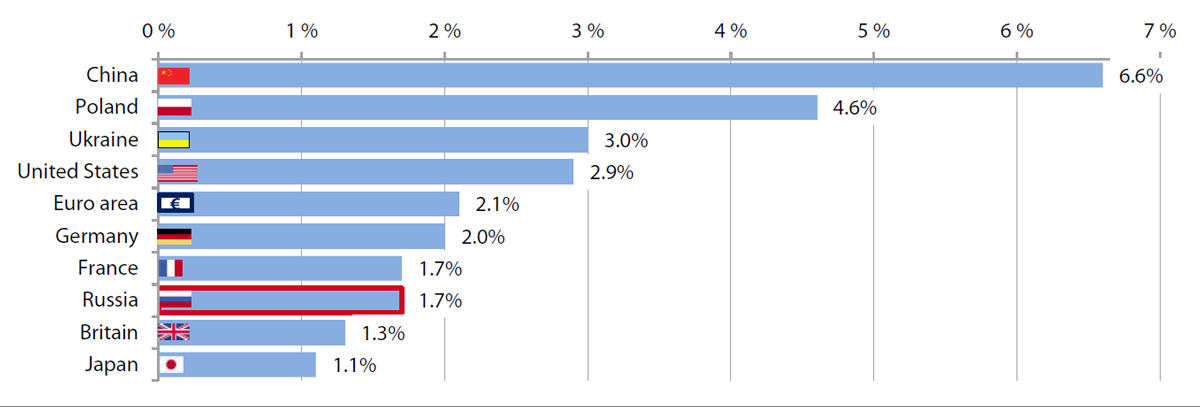

Figure1 : GDP (Change to Previous Year)

Figure 2: GDP Forecast 2018 (% Change on 2017)

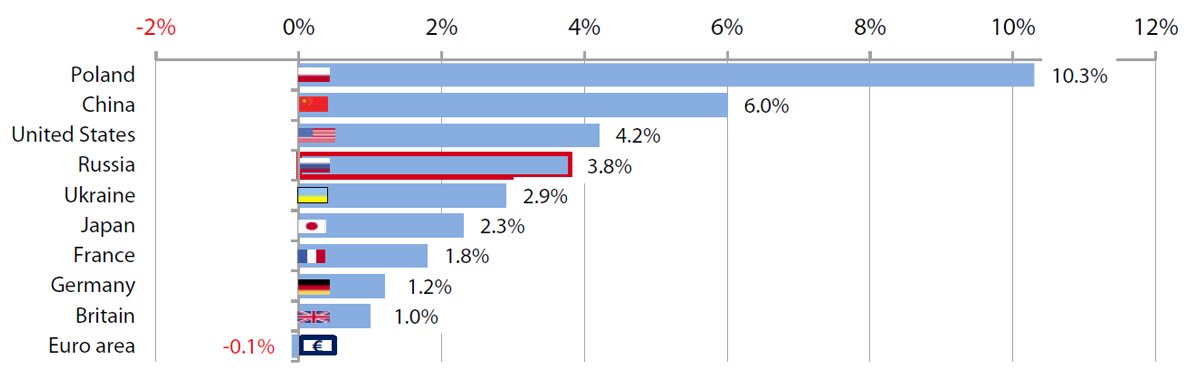

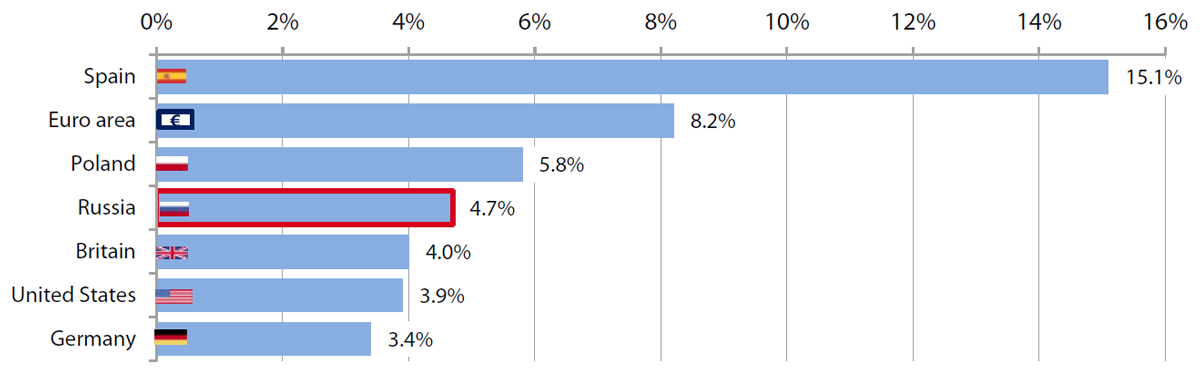

Figure 3: Industrial Production (Latest Figures, July 2018) (% Change on Year Ago)

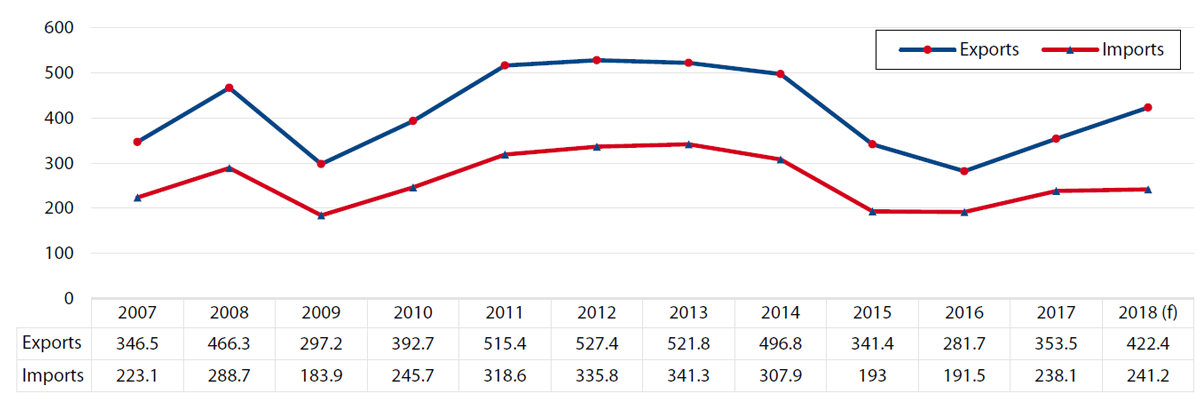

Figure 4: Foreign Trade (USD Bln.)

Finances

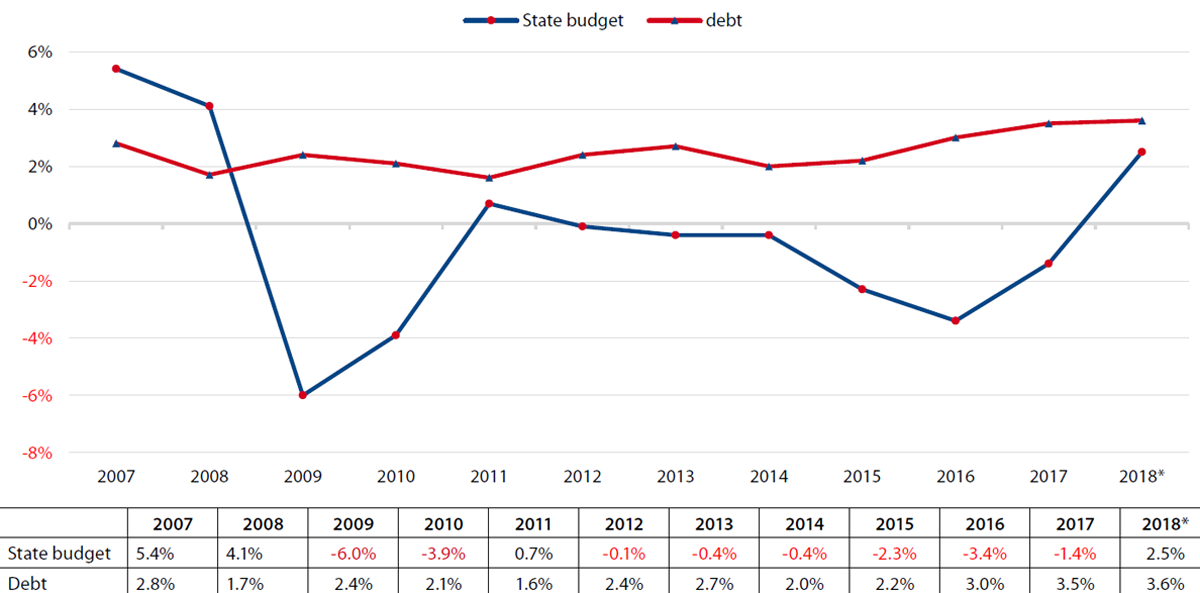

Figure 5: Balance of State Budget and External Debt (Federal Govenrment Only; as SHare of GDP)

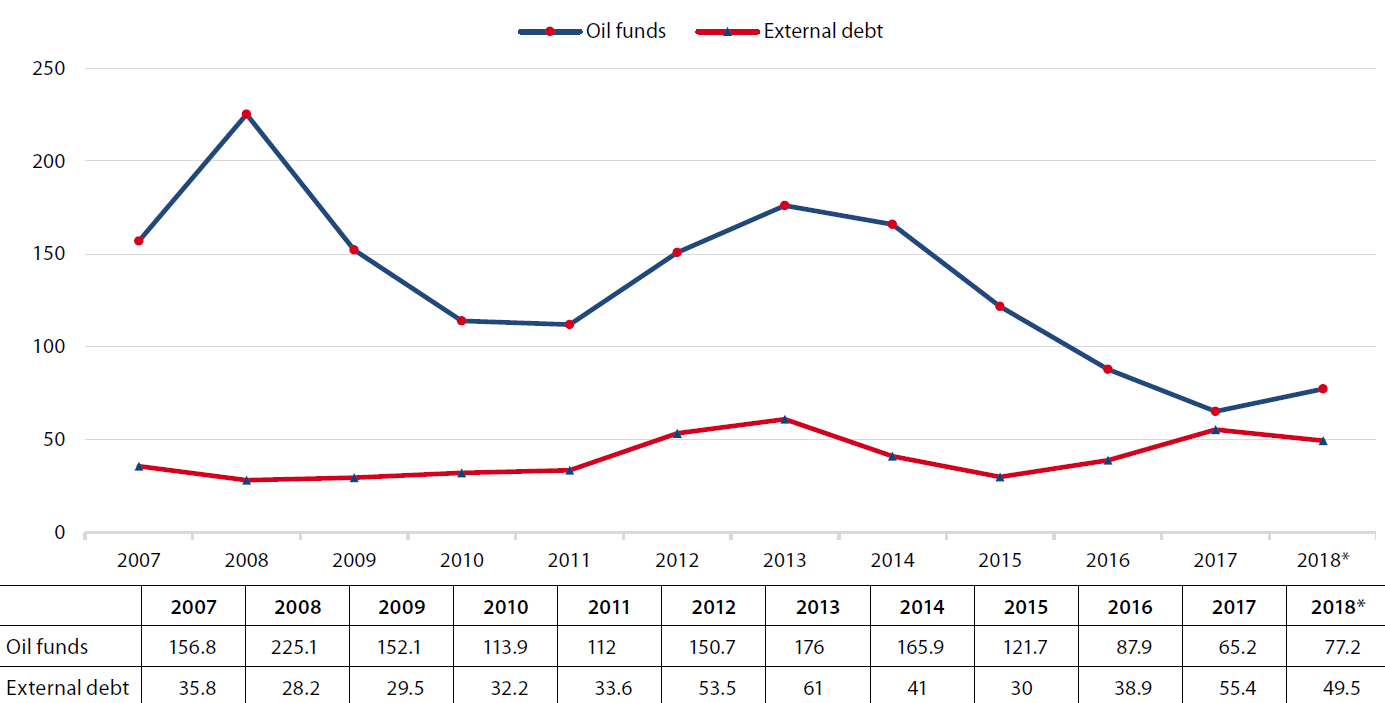

Figure 6: External Debt and Value of State Oil Funds (in Bln USD)

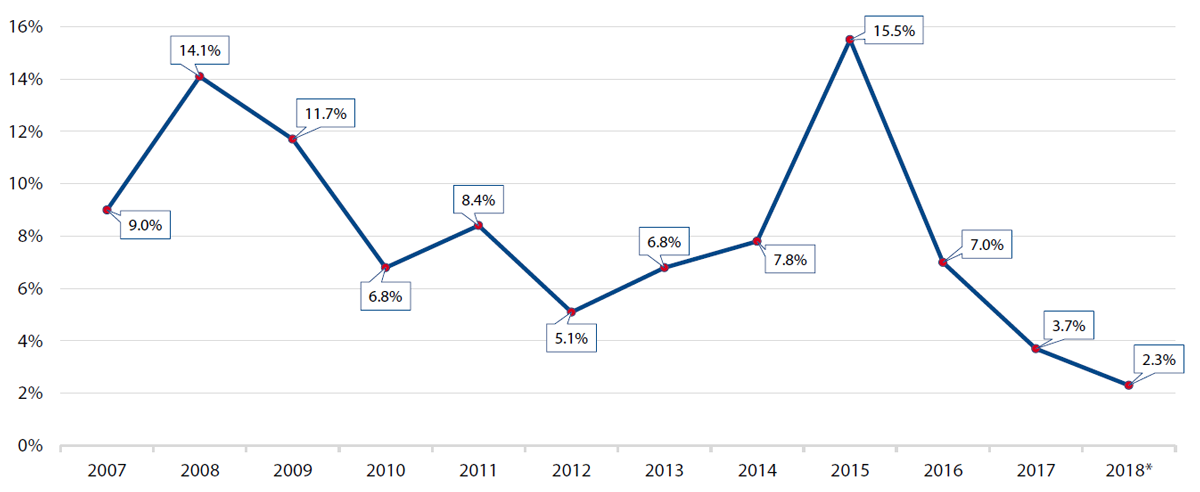

Figure 7: Consumer Price Inflation

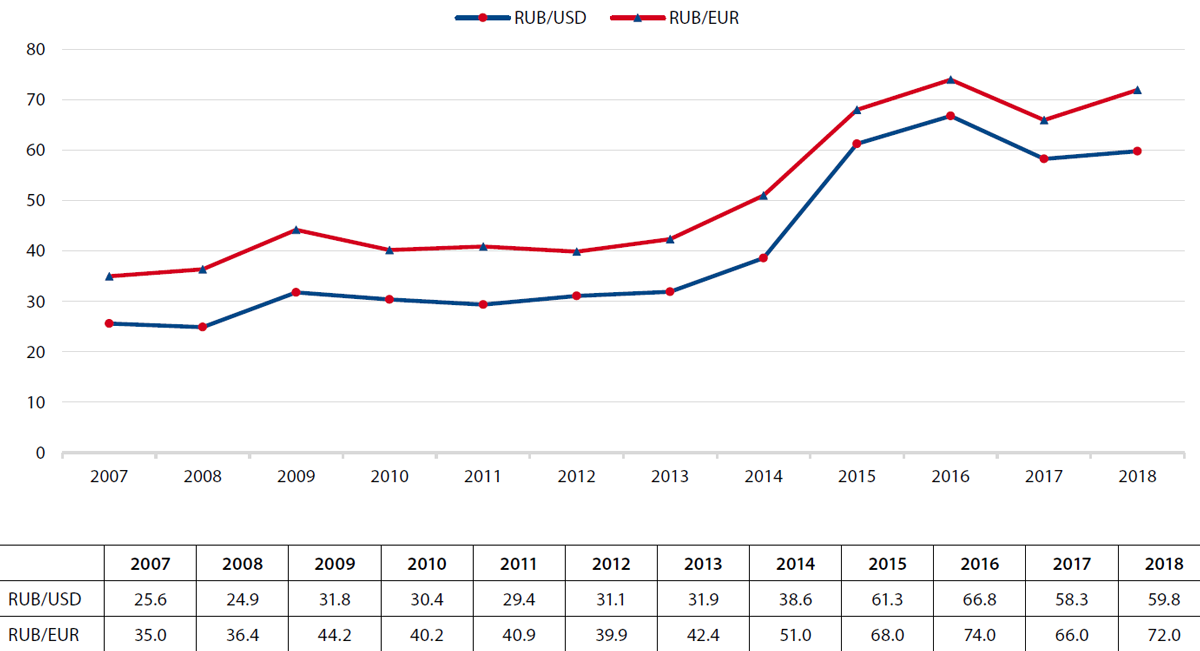

Figure 8: Exchange Rate

Social Data

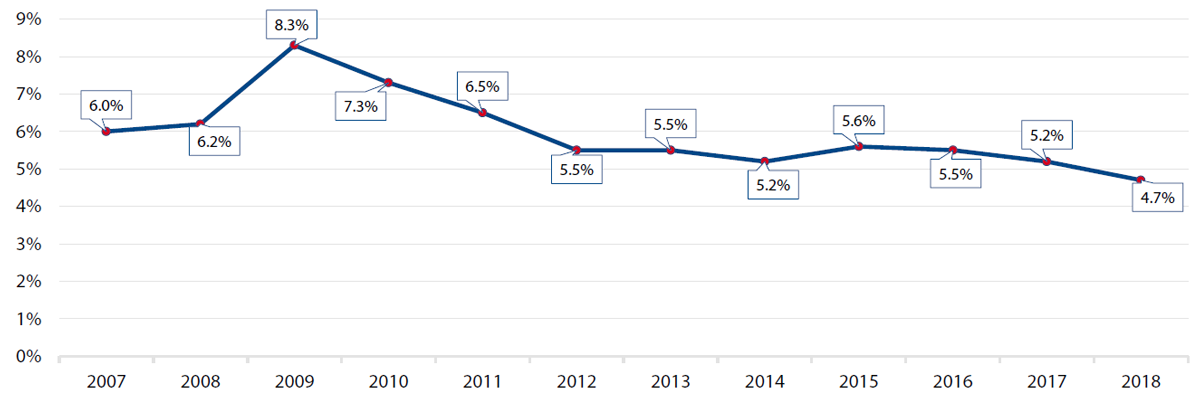

Figure 9: Unemployment Rate (ILO Method)

Figure 10: Unemployment Rate (Latest Figure, July or August 2018)

Figure 11: Average Monthly Wage (Converted into USD)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.