Russian Analytical Digest No 213: 2017 in Review, Perspectives for 2018

19 Feb 2018

By Vladimir Gel’man, Richard Connolly and Aglaya Snetkov for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 7 February 2018.

2017 Year in Review: Russian Domestic Politics

By Vladimir Gel’man

Abstract:

2017 was a year of tactical successes for Russia’s authoritarian regime. On the domestic front, it remains unchallenged, despite continuing economic problems, growing protests and increasing disappointments among elites and masses. Although the Kremlin has effectively averted risks prior to the upcoming March 2018 presidential elections, the major challenges lie ahead.

On the Eve of Presidential Elections

According to the calendar of events in Russian domestic politics, the year of 2017 was an interlude between State Duma elections (conducted in September 2016 and resulted in a landslide victory of United Russia) and presidential elections, scheduled for March 2018. Aiming to further strengthen the power of Vladimir Putin and to avoid any post-election protests that might even slightly resemble those of 2011–2012, the Kremlin concentrated on the upcoming presidential campaign as the major task of all state-driven political machinery. At first sight, this should not be a risky game. Given the high popular approval rates of Putin, the seeming lack of viable alternatives to the political status quo in light of the notorious weakness of the opposition in Russia, and the successful implementation of a policy of lowscale repression as a tool of the regime’s preemptive control over dissent, the Kremlin should easily maintain its dominance over Russia’s political landscape. Nevertheless, the regime feels itself to be vulnerable and these feelings increased in 2017, against the background of sluggish economic recovery and increasing disappointments among both elites and masses.

Within the context of a presidential campaign, the Kremlin found itself between a rock and a hard place. On the one hand, it is faced with increasing political demobilization given the non-competitive nature of elections— the voter turnout during the 2016 State Duma elections was 48 per cent, the lowest-ever in post-Soviet history (and in the large Russia’s cities, it was even lower). Presidential elections should not be a boring ritual similar to Soviet-style elections without choice and intended to bring as many voters as possible to the polling stations so that Putin can claim a renewed legitimacy. On the other hand, the amount of carrots available for buying the loyalty of Russian voters is much lower than during previous elections, and the regime has been forced to rely upon the extensive use of sticks towards its rivals.

The scope of the repressions in 2017 was not so harsh, in terms of the numbers of political prisoners or victims of political violence, but were highly sensitive for all real and/or potential challengers of the Kremlin. In September 2017, a major star of the Russian theater, the nonconformist Moscow stage director Kirill Serebrennikov was put on criminal trial, due to accusations of misappropriating state funds. The former technocratic minister of economic development, Alexey Ulyukaev was sentenced to eight years in jail in December, because of criminal charges of bribery relating to the privatization of large block of shares of the state oil company Rosneft. The renowned European University in St. Petersburg, a private graduate school in social science and humanities, lost its educational license during 2017 and has been evicted from its premises in the city center of St. Petersburg. Experts argued that all of these cases were manufactured by the law enforcement agencies, as well as by interest groups (in Ulyukaev’s case, by Rosneft top management), in order to produce demonstrative effects as part of a state-induced politics of fear. Western-minded intellectuals, being afraid of a further “tightening of the screws”, opted for emigration or at least lowering the tone of their critical voices, and have avoided joining the camp of protesters. At the same time, independent media faced further shrinking of freedom of speech. RBK holdings, previously controlled by the former presidential candidate Mikhail Prokhorov, changed its owner and editorial line. The popular Echo Moskvy radio station faced financial troubles, and one of its leading journalists, Tatyana Felgenhauer, was attacked by a stranger with a knife while in the office. Attempts to increase state control over the Internet and social media continued throughout the whole year. Also in 2017, there was a continuation of vicious violent attacks by pro-Kremlin militants at “unwanted” cultural events and entities, as well as against political activists (such as Alexey Navalny), without serious prosecution by the Russian authorities.

Apart from countering real or potential dissent, the Kremlin invested new efforts into the strengthening of the “power vertical”, the hierarchy used to govern not only the economy, but also political processes across Russia’s regions and cities. In 2017, more than twenty regional chief executives (including some long-standing holders of these jobs) left their posts and were replaced by younger officials, often without major political experience. In most instances, the delivery of votes in elections is considered as the main task for new appointees. Meanwhile, the centralization of the state control, launched in the early 2000s, reached the last bastion of regional autonomy, Tatarstan. In 2017, the Kremlin refused to prolong the bilateral treaty on the division of power between Moscow and Kazan (first signed in 1994, and then confirmed twice after that, it was the only legal act of this kind, which remained in force until 2017). Later in the year, the mandatory titular language classes in schools in all ethnic republics of Russia were officially cancelled at Putin’s request, thus causing major disappointments in Tatarstan. The efforts of the republican leadership to protect the special status of Tatarstan (let alone the status of all other republics, except for Chechnya) proved to be in vain. However, despite this growing disappointment among elites and the continuing struggles between rent-seeking actors, there is no sign of open or latent disloyalty among Russia’s ruling class on the eve of the presidential elections.

Protests Rising

Economic problems continued in 2017, despite the rise in the global oil price up to $60+ per barrel (to some extent fueled by the deal between Russia and OPEC) and the major efforts of the Central Bank of Russia to target inflation (about 3 per cent in 2017, the lowest ever index in post-Soviet history). The optimistic signs of economic growth in early 2017 had become skeptical accounts by the end of the year, especially given the new wave of decline in the real incomes of Russians, expectations of a further deepening of international economic sanctions and the uncertain prospects for the future. As a result, 2017 saw an increase in economic and labor protests across Russia’s regions. Most of these actions remained local and/or issue-based by nature and have not challenged the regime, as such being more or less minor nuisances for the Kremlin. Even social protests in major cities (such as meetings against the housing renovation program in Moscow or against the takeover of St. Isaac’s cathedral in St. Petersburg by the Russian Orthodox Church) mostly had local, rather than nationwide significance and did not affect Russia’s political landscape much.

However, the political movement, formed around opposition leader Navalny, became a major troublemaker for Russia’s authorities in 2017. Early in the year, Navalny announced his intention to run in the 2018 presidential elections, and launched a major campaign tour across Russia’s regions, accompanied by mass meetings and public gatherings. His team opened campaign headquarters in 80+ major cities, and effectively used Youtube videos and other Web resources as means of communication and mobilization. In March 2017, Navalny posted online the documentary video, On vam ne Dimon, which openly accused the prime minister Dmitry Medvedev of various instances of corruption. The video, watched by 20+ million viewers, was met with no official responses from the Kremlin and/or law enforcement agencies. Navalny, in turn, called for protest actions, which were held on 26 March and 12 June 2017 in a number of Russian cities. Surprisingly for many observers, these actions brought to the streets many young people, attracted by Navalny’s claims and political style. Some observers even considered these tendencies as early signs of a “revolutionary situation”, in light of the centennial jubilee of the 1917 Russian revolution, but in fact they have not reached the level of a major anti-system mobilization. Meanwhile, the Kremlin effectively blocked Navalny’s participation in the presidential elections. In spite of his low public approval rate, the very possibility of real electoral competition was considered by Kremlin’s strategists as an existential threat to Russia’s political regime. Although public gatherings in twenty Russian cities officially nominated Navalny’s candidacy, the Central Electoral Commission banned him from balloting, because of a law prohibiting Russian citizens with a criminal record of serious offences from running in elections. In 2013, Navalny was charged with a criminal offence and got probation instead of incarceration, but, in 2016, his legal case was overturned by the European Court of Human Rights. Deprived from running in elections, Navalny called for an “active boycott” of the elections and protest actions on the eve of elections, thus turning his temporary campaign network into a regular opposition political movement.

The call for a boycott coincided with an increase in expectations about the predictable outcome of the elections: according to a Levada Center survey, conducted in December 2017, 75 per cent of those Russian voters, who intended to participate in March 2018 elections, preferred to vote for Putin (the next potential candidate, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, was endorsed by 10 per cent of voters). It contributed to warnings regarding low voter turnout (the same survey demonstrated that only 30 per cent of respondents “definitely” intended to vote, and another 28 per cent declared that they were “likely” to go to polls). The Kremlin needed new figures on the ballot, who may attract the interest of voters. This is why the Communist Party of Russia replaced its 73-yearold leader Gennady Zyuganov with the previously little known 57-year-old agricultural businessman, Pavel Grudinin (formerly a regional lawmaker from United Russia) as its candidate. At the flank of the so-called “systemic liberals”, apart from long-standing Yabloko leader Grigory Yavlinsky, 36-year-old TV star Xenia Sobchak, the daughter of Putin’s former boss Anatoly Sobchak (city mayor of St. Petersburg in 1991–1996), declared her candidacy under the label of “against all” existing candidates, with a conspicuously pro-democratic and pro-Western political program. However, many analysts predict that the increase in voter turnout in March 2018 may be achieved largely through the widespread use of workplace mobilization to ensure employees turn up to vote, especially in the public sector, as well as by mass practices of electoral fraud. To what extent the Kremlin will be able to avoid post-election protests remains to be seen.

Challenges Lies Ahead?

As for Putin, in 2017, he did not launch any major new initiatives in domestic politics, and his policy promises before the presidential campaign remain intentionally vague. The only exception was the introduction of state payments for low-income families with newborn children from 2018 (accompanied with the prolongation of the maternity capital program until 2021). However, the contours of the economic policies under the new government (as well as the composition of the government after the 2018 elections) are still uncertain. In 2017, two major teams of experts proposed policy programs for Putin, based on hardly compatible agendas. The Center for Strategic Research, led by the former minister of finance Alexei Kudrin, proposed structural reforms, alongside major institutional changes aimed at economic (and, to a lesser degree, political) liberalization and overcoming the international isolation of Russia. Alternatively, the isolationist and statist Stolypin Club, grouped around Boris Titov and Sergey Glazyev, suggested a major increase of state investments into hightech industries and the stimulation of domestic consumer demand as would-be drivers of economic growth. However, Putin has not disclosed his actual policy preferences and it is unlikely that he will initiate major policy changes after his expected reelection in 2018.

Overall, in 2017, Russia did not experience any key changes in domestic politics. The Kremlin kept its firm control over political processes and did not encounter irresolvable problems in the short term, at least, before the March 2018 presidential elections. The inertia created by two previous choices made by the Russian leadership—in 2012, when the regime’s partial liberalization was shifted to a repressive politics of fear, and in 2014, when Russia sacrificed the policy of prioritizing economic growth and development for the sake of geopolitical adventures—continue to determine the conduct of domestic politics and are likely to cast their shadows for a longer period of time. This does not mean that the regime will avoid major challenges to its dominance in the long term—sluggish economic growth, generational changes, and international sanctions may contribute to political changes, but not immediately. As of yet, the desire of Russian leaders to preserve the political status quo and consolidate their power under authoritarianism has met few obstacles.

About the Author:

Vladimir Gel’man is professor at the European University at St. Petersburg and at the Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki.

Stagnation and Change in the Russian Economy

By Richard Connolly

Abstract

The Russian economy returned to growth in 2017 after a prolonged recession. However, the pace of recovery unexpectedly subsided in the second half of the year despite favourable external conditions. As a result, many observers now fear that the Russian economy is stagnant and that only structural reform will reignite growth to levels approximating or in excess of the global average rate of growth. Nevertheless, several areas of the Russian economy are performing extremely well, suggesting that the characterisation of a stagnant economy may be too simplistic and missing some important areas of change.

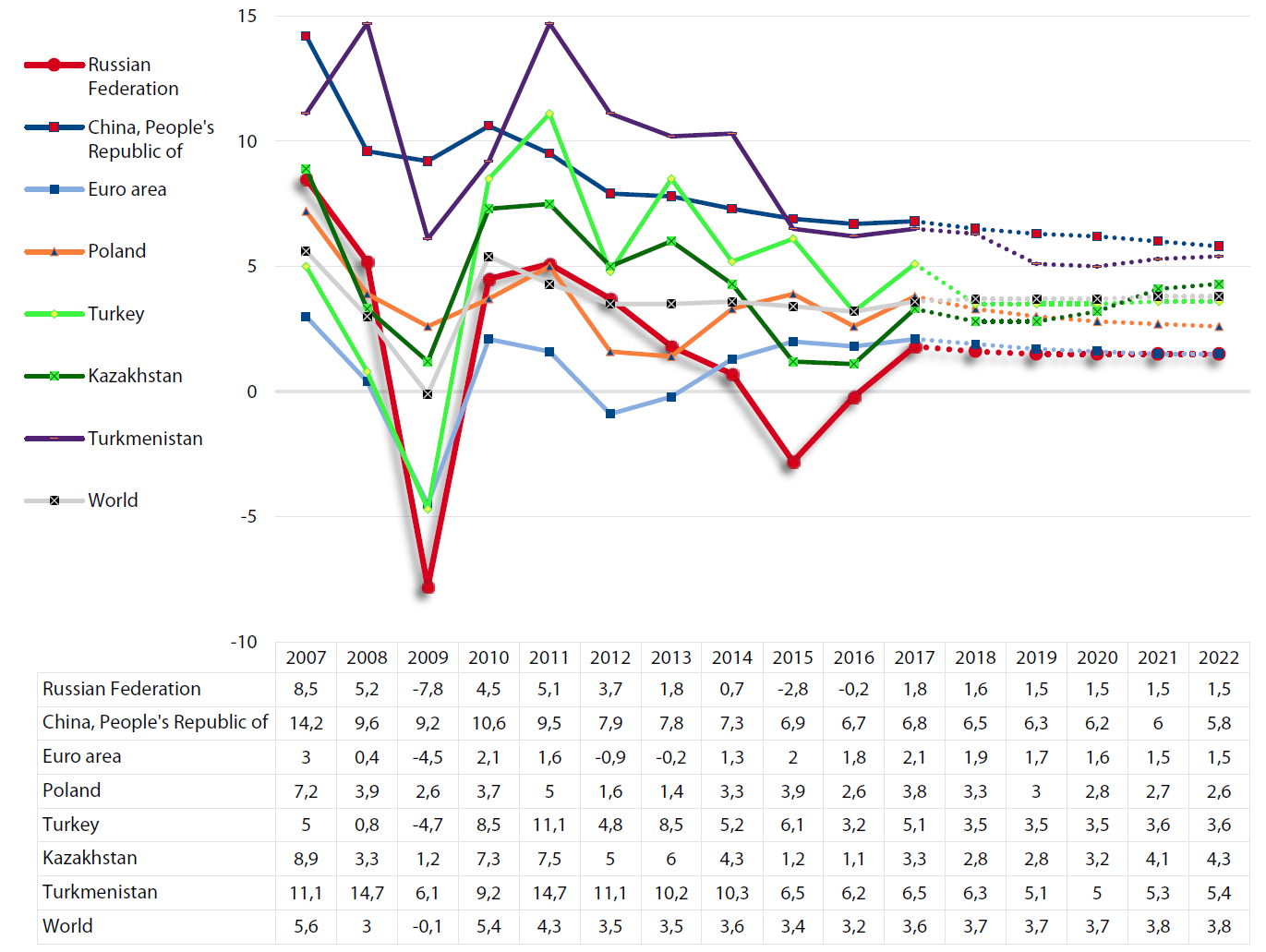

After a protracted recession that began in early 2015, the Russian economy returned to growth in 2017. However, the estimated rate of GDP growth—1.5 per cent—was lower than many had hoped for earlier in 2017, when some of the more optimistic forecasts, such as those produced by Russia’s Ministry of Economic Development, suggested that the economy might expand by as much as 2 per cent. Despite oil prices hitting their highest level since 2014, official forecasts—both from within Russia and from international agencies—suggest that growth will continue at its current anaemic pace into 2018. This poorer-than-expected performance has led many observers to suggest that the Russian economy is essentially stagnant, and that the prospects for economic growth will remain bleak until the leadership engages in significant structural economic reform. While this is an obvious conclusion to draw when examining aggregate data, closer inspection of the economic data reveals that considerable change is taking place across the Russian economy, with a number of important sectors growing at a brisk pace.

Macro-Level Stagnation…

The Russian economy recorded annual GDP growth in 2017 for the first time in three years. The most recent Rosstat estimate, released at the beginning of February, indicates that GDP expanded by 1.5 per cent. This was towards the lower end of the range of most official forecasts made at the beginning of the year, when annual growth of between 1.5–2 per cent was forecast. In the summer, it had looked as though growth would surpass expectations after the economy recorded brisk growth in the first half of the year. However, the rate of year-on-year growth slowed considerably towards the end of the year, dampening any sense of optimism that the economy might quickly return to a pre-recession level of output.

This slowdown at the end of the year was all the more disappointing, because it took place against a backdrop of improving external conditions.

First, the deal between Russia and OPEC to reduce crude oil output, concluded at the end of 2016, began to achieve its intended objective of reducing global crude inventories, which in turn exerted upward pressure on spot prices for crude oil across the world. In 2016, the average price for Urals crude was $42.1 per barrel; in 2017, this rose by 21 per cent to $53.3 per barrel. In the past, an annual increase in the price of Russia’s primary export product would have generated faster GDP growth.

Second, the wider global economic growth picture improved as the year progressed. According to the IMF, global growth was expected to accelerate by 0.4 percentage points in 2017, reaching 3.6 per cent. This was expected to rise to 3.7 per cent in 2018. The strong global growth performance saw Russia’s main trading partners— the Eurozone economies and China—grow at an estimated rate of 2.4 per cent and 6.8 per cent respectively. In both cases, performance exceeded most forecasts made at the beginning of the year. Ordinarily, an improvement in the fortunes of Russia’s main trading partners would result in faster growth in Russia, not the slowdown observed at the end of the year.

Third, Russia’s economic performance in 2017 was much weaker than the populous middle-income countries located near Russia, such as Poland (estimated GDP growth of 4.1 per cent in 2017) and Turkey (5.1 per cent), and was also weaker than neighboring natural resource-exporting economies like Kazakhstan (3.5 per cent) and Turkmenistan (5.7 per cent).

Thus, although Russia avoided the economic apocalypse that some observers had predicted would ensue when Russia was hit by a combination of Western sanctions and declining oil prices in 2014, and is now on a path of slow but steady recovery, it is also clear that something is holding back aggregate economic performance, even as external conditions have improved.

Identifying the sources of Russia’s seemingly anemic economic performance demands detailed examination of economic data, not least because headline figures can often conceal important developments at more finegrained levels of analysis.

Looking at the main indicators, the obvious culprit for the deteriorating performance in the second half of the year was industrial production, and, more specifically, manufacturing. Annual growth in industrial production amounted to a mere 1 per cent, which was especially poor considering that this was a slightly slower rate than that recorded in 2016—a year in which the economy contracted on aggregate—when industrial production grew at 1.1 per cent.

There are two immediate explanations for the decline in industrial production in the second half of the year. First, oil extraction—which constitutes a major component of industrial production—did not grow in 2017, due to Russia’s commitment to reducing output as part of the deal with OPEC. This also dragged output down in other areas of the economy that are highly correlated with oil extraction, especially oil extraction equipment. Second, unseasonably mild weather in the winter dampened demand for fuel and heating across the country.

Furthermore, there was considerable variation in performance across different branches of industry. Strong performance in gas extraction (annual growth of over 8 per cent), as well as in other mining branches (coal production, for example, rose by over 6 per cent), meant that output in extractive industries expanded by around 2 per cent. However, manufacturing barely grew at all (0.4 per cent). Consequently, despite a high-profile import substitution campaign and elevated spending on the procurement of armaments, the volume of manufacturing production remained well below pre-recession levels.

Other headline figures for 2017 also dampened optimism that the recovery from recession would be robust. Investment in fixed capital grew by 3.5 per cent over the course of 2017, causing the fixed investment share of GDP to rise slightly from 21.6 per cent in 2016 to 21.8 per cent. Given that most economists would agree that Russia needs to be investing around 25–30 per cent of GDP annually for a sustained period of time to achieve anything approximating modernization, the modest growth in investment is clearly insufficient. Indeed, the pace of this recovery in investment is slower than might be expected, not least because the protracted length of the slump in investment that took place over 2014–2016 would suggest that significant latent demand for investment exists. Furthermore, mirroring the trajectory of industrial production, the pace of investment growth slowed at the end of 2017 as investment by the state and large firms declined. It is possible that investors might be waiting for signs that the recovery is well and truly underway before committing themselves to long-term investment projects. But there are also legitimate fears that investment is not being held back by a lack of ‘animal spirits’, but instead by structural constraints, such as weak property rights and poor access to capital for small and medium-sized enterprises.

On the positive side, living standards continued to improve, albeit in an uneven and fitful fashion. Inflation dropped to a post-Soviet low level of 2.5 per cent, retail sales registered modest growth of 1 per cent, and the recorded unemployment rate remained at a post- Soviet low of close to 5 per cent. Household consumption grew by 3.4 per cent. The state of federal government finances also turned out better than had initially been expected, with a federal budget deficit of no more than 2 per cent of GDP expected for 2017, considerably lower than the deficit of 2.5 per cent forecast by the Ministry of Finance earlier in the year. This improvement in fortunes was driven primarily by the increase in tax revenues derived from oil extraction and exports, the value of which exceeded official forecasts made earlier in the year.

Overall, then, it would appear quite justified to describe the Russian economy as ‘stagnant’. Consumption and investment grew, but at a much slower rate than might be expected after a protracted recession, and certainly at a slower rate than would usually take place when oil prices rose by over 20 per cent. And although federal government finances are in better shape than some had feared, the fact that the government is conducting a relatively contractionary fiscal policy has done little to help trigger an improvement in business confidence. In short, the macro figures presented here suggest that the Russian economy is limping out of recession and remains vulnerable to any turbulence on global oil markets that might threaten the few green shoots of recovery observed to date.

…Concealing Micro-Level Change

However, while this picture roughly corresponds with the conventional narrative on the prospects for the Russian economy—that it is stagnant and vulnerable to reversal—the reality is more complicated.

For instance, while it might be tempting to conclude that Russian manufacturing in particular is in the doldrums, despite the best efforts of the government to support it, closer inspection reveals that certain pockets of manufacturing are booming. Output in the pharmaceutical and automobile industries—areas where the government has focused particular attention in recent years—both grew by over 12 per cent. Output in rubber and plastic products grew by over 10 per cent, after registering over 5 per cent growth in the previous year. Output in the chemicals industry grew by over 4 per cent, continuing a trend of consecutive annual growth that stretches back to 2010. A similar trend is evident in food processing, which has grown every year since 1998. Outside manufacturing, other service sectors of the economy also performed well. Transportation and storage services, for instance, grew by 3.7 per cent, while information and communication services grew at a rate of 3.6 per cent.

Much has been made in recent years by the leadership of Russia’s progress in the agricultural sector. Growth in output that defied the wider downturn in economic performance over 2015–16 continued, albeit at a slightly slower rate than in 2016. Overall agricultural output grew by 2.4 per cent, a slower rise than the 4.7 per cent growth recorded in 2016. Although this meant that the pace of growth across most categories of agricultural production slowed, the grain harvest delivered a post-Soviet record of 130 million tons.

To be sure, strong performance in these areas has not proven sufficient to generate more robust aggregate performance. However, the fact that certain segments of the economy are booming indicates that the simple story of stagnation may be misleading. What may be closer to the truth is that this is an economy undergoing a slow and for some industries—such as metallurgy and tobacco production—painful process of restructuring. The sectors that are performing better than average tend to be located in either the higher value-added segments of manufacturing or in the services sector. These are areas where continued growth might, if sustained, help generate a more sophisticated and diversified economic structure.

Prospects for the Year Ahead

As usual, developments on the global oil market will shape the outlook for the Russian economy. While global inventories of oil have fallen, they remain high by historic standards, prompting the extension of the Russia–OPEC deal to the end of 2018. Forecasters are divided on what is likely to happen in the coming months. Recent forecasts from the International Energy Agency (IEA) suggest that inventory levels may rise in the coming months, despite the output cut. If so, oil prices are unlikely to rise significantly, and could even fall. By contrast, more bullish forecasters, such as Goldman Sachs, are predicting that prices will continue to rise over the course of the year. Indeed, if inventories continue to fall, a closer gap between supply and demand could result in any geopolitical shocks—unrest in Iran or Venezuela, for example, or conflict on the Korean peninsula— generating disproportionately strong upward pressure on prices.

Domestically, some observers are hopeful that a comfortable win for Vladimir Putin in the presidential election in March will presage a significant change in economic policy. Given the revealed preference for a mix of conservative macroeconomic policies and incremental, technocratic institutional changes (e.g. making progress in the World Bank Doing Business Index), it remains unlikely that any significant structural reforms will be announced. This will not stop those close to the leadership generating plans to boost the rate of annual economic growth to over 3 per cent. However, while some progress in macroeconomic reform might be expected— for instance, the Finance Minister, Anton Siluanov, has hinted at plans to reform the taxation system and to reorient federal government spending towards health, education and infrastructure—meaningful progress in implementing micro-level and structural reforms—i.e. improving property rights, strengthening the rule of law, and so on—is less likely. Strong entrenched interest groups close to the leadership, as well as the economic requirements of meeting the leadership’s foreign and security policy objectives, are all likely to constrain any reformist impulses. Indeed, in January, it was rumoured that the president informed high-profile executives that they should not expect any significant change in the business environment in the near future.

Instead, any economic stimulus from the authorities is likely to come either from targeted injections of federal government spending on socially- and politicallyimportant constituencies as part of the presidential election campaign, or from the Central Bank. Assuming no sharp fluctuations in the oil price, the current and historically low rate of inflation should give the Central Bank room to continue reducing interest rates from the current level of 7.75 per cent (compared to 10.5 per cent a year ago).

Western sanctions—especially the prospect of tighter US sanctions—will remain an important factor, if for no other reason than that sanctions, and even simply the threat of them, do tend to force the Russian authorities to undertake new economic policies. The import substitution campaign, as well as vigorous efforts to cultivate closer economic ties with non-Western countries, both emerged in response to sanctions. According to Anton Siluanov, the authorities must make greater efforts to improve the business environment to make Russia a more enticing destination for investment, for both foreign and domestic investors. This would, he argued, reduce the impact of any additional sanctions imposed by the US in the near future. As a result, the authorities are planning another capital amnesty to attract the repatriation of capital held by Russian citizens offshore. Measures to use state-owned banks to execute defence order transactions, as well as to reduce the transparency of state-owned enterprises, were also put in place in response to sanctions. It is likely that any future sanctions will impel the Russian authorities to craft new responses that may have a significant impact on the business environment.

Conclusion

To sum up: Russia’s economy looks set to continue a slow and uneven recovery from a protracted and painful recession. While a sudden fall in oil prices could set this recovery back, the relatively conservative macroeconomic policies set by the Ministry of Finance and the Central Bank mean that the authorities should be well placed to respond to any deterioration in the economic outlook. Furthermore, although the aggregate picture remains underwhelming, especially by the standards of Russia’s previous post-recession recoveries, the fact that a number of sectors are recording robust growth in output indicates that the economy is far from stagnant.

About the Author

Richard Connolly is director of the Centre for Russian, European and Eurasian Studies at the University of Birmingham. He is also associate fellow on the Russia and Eurasia program at Chatham House and visiting professor at the Russian Academy of the National Economy in Moscow.

Figure 1: Real GDP Growth of Russia and Selected Regions and Coutries (2007 – 2022, Annual Per Cent Change)

Russia’s Foreign Policy—Current Trajectory and Future Prospects

By Aglaya Snetkov

Abstract

A central theme in debates about Russia’s foreign and security policy in 2017 has been the role it has played within ongoing international crises, with analysts seeking to discern whether Russia’s foreign policy is predominantly a product of ad hoc pragmatism and opportunism or a more systematic and long-term anti-Western perspective. As argued in the article the answer is that it is a mixture of both. The Putin regime is on the one hand seeking to continue playing a pivotal role in individual security crises whilst on the other hand endeavouring to sustain its international position and further broader global alliances, often from a position of weakness.

Introduction

A central theme in debates about Russia’s foreign and security policy in 2017 has been the role it has played within ongoing international crises, notably Syria, North Korea and Ukraine. This has been accompanied by continued focus on Russian interference in the 2016 US election. In both contexts, analysts have often been concerned with adjudicating whether or not Russia is a victor or a loser. Against this background, an important question has become assessing the extent to which Russia’s foreign policy is a product of ad hoc pragmatism and opportunism or a more systematic and longterm anti-Western perspective. The answer suggested by this article, it that it is a mixture of both. In spite of the prevalence of concerns about the relative decline of the West and its global influence, Russia—unlike China— does not have the capabilities to set itself up as an effective counter-weight to the US. Instead, echoing Lukyanov, this article suggests that Russia is now focused on creating ‘fuzzy alliances and flexible relations’, in which it can continue to play a pivotal role within individual issues or crises. However, this selectivity does not represent a substantial long-term challenge to the influence of major powers, such as the US or China. This article will survey Russia’s foreign policy across the increasingly diverse relations that the Putin regime is seeking to establish.

Russia’s Relations with the West

The context in which Russia has been most frequently mentioned this year has been the ongoing fallout from the unexpected election of Donald Trump to the US presidency in 2016, and Russia’s purported role in this coming to pass. Whilst the Putin regime may have hoped for a renewal in its relations with Washington with Trump in the White House, 2017 has turned into one of the most problematic years in the US–Russia relationship since the end of the Cold War.

Whilst some in the Trump administration, such as Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, have continued to argue that it is the Ukraine factor that is ultimately preventing a normalization of relations between the two sides. In practice, it is virtually impossible to envisage a significant change in relations now that “the Russia factor” has become so central to US domestic political debate about the nature of the Trump administration and the extent to which it was willing to collude with a foreign power to interfere in the American domestic electoral process. As a result, the Russia factor has become poisonous among the domestic political milieu in Washington DC. Indeed, regardless of what the Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russia’s meddling in the election uncovers, the scope for a rapprochement in the short term is extremely unlikely. Added to this, as Alexander Gabuev suggests, there’s less and less knowledge and expertise in Moscow and Washington DC about one another. This is serving to consolidate the trend of painting one another in simple and antagonistic terms.

Until there is some resolution in the machinations about the election, the Trump administration has its hands tied when it comes to its policy towards Russia. Hence, 2017 has seen the passing of the Russian Sanctions Review Act into law in August and the prospect of a new round of sanctions targeting Russian elites in early 2018, the tit-for-that clampdowns on embassies and expulsions of embassy staff, the US agreement to supply lethal weapons to Ukraine and the labelling of Russia alongside China as the main security threats to the US, over and above terrorism. All in all, the impact of Trump’s election to the Presidency thus far has been a further souring of relations, rather than a new start.

Beyond the domestic US context, the wider relationship between Russia and West also remained at an alltime low across 2017. Indeed, as Kortunov suggests, the Russian official position continues to characterize the current choice in world affairs as one between order and chaos, with the West representing chaos, and Russia representing the path towards ‘developmental pluralism’. In Europe, whilst the predicted wave of (Russianbacked) populist parties sweeping to power across the continent did not materialize, concerns remain regarding the ongoing links between populist regimes in Eastern and Central Europe and the Putin regime. Against this background, Russia continues to be seen through the lens of representing a geopolitical threat, with fears mounting about cyber security and information/hybrid warfare challenges emanating from Russia. While the Kremlin views the continued sanctions regime and the build-up of NATO capabilities and forward resilience in Eastern Europe as undermining any amelioration in relations.

Relations with the Middle East

Russia’s role in Syria also remained a prime focus of 2017. In spite of commentators’ suggestions at the start of its campaign in 2015 that Russia will inevitably become bogged down in a quagmire, akin to its disastrous campaign in Afghanistan in the 1980s, this has not transpired. From the perspective of the Putin regime, not only has it demonstrated Russia’s willingness to use force abroad. It has also demonstrated its ability to take advantage of the West’s reluctance to become directly involved in conflicts in recent years, to the end of successfully propping up a regime of its choosing. Indeed, with the Assad regime now on a much surer footing, the Putin regime has hailed its operation on the ground as a success and announced, in November, a drawdown of its military campaign.

Although the intervention has shown Russia’s continued ability to play a significant role in a specific security crisis, questions remain as to what lies ahead for the Assad regime. Moscow has sought to promote the Sochi and Astana meetings in parallel to the Geneva talks, in order to position itself as a key broker in any future peace settlement. However, these alternative formats have only served to highlight the difficulties that Russia has in presenting itself as a neutral arbiter, in light of its military intervention on the side of the Assad regime. It has, therefore, struggled to bring all the various parties active in the Syrian crisis to the negotiating table, particularly opposition and rebel groups. Indeed, as Trenin notes, winning the peace in Syria is turning out to be much more problematic than winning the war for Russia.

In addition, Russia does not have the capacity to single- handedly fund a reconstruction and rebuilding plan for Syria, and is thus reliant on Western and regional actors coming on board. This means that in order to capitalize on the short term successes of its military intervention, Russia remains beholden to others in order to establish a stable post-conflict situation. Thus, although having acted militarily to have a big impact on the course of the conflict, Russia is both unwilling and unable to become the predominant power in the wider Middle East, preferring instead to share the burden for ensuring stability and orders with others.

Alongside its apparent successes in Syria, Russia’s policy towards the wider Middle East also garnered significant attention in 2017. Whilst it seeks advantage out of the West’s ongoing reluctance to become more actively engaged in the region, Russia, as Kozhanov notes, has adopted a pragmatic and transactional Middle Eastern policy. In this way, it has sought to balance a very diverse and seemingly incompatible set of relations with actors, including Iran, Turkey, Israel and Saudi Arabia. Ultimately, this approach is a product of the Putin regime’s recognition that Russia has neither the long-term interests, nor the influence of the US in the region, or even that of the ever growing economic power of China. In this context, Russia follows a policy aimed at drawing short-term benefits through a pragmatic juggling act, but without a concerted, long-term and strategic dimension. Russia is, therefore, unlikely to become a fully engaged power in the Middle East, irrespective of its occasional interventions in individual crises and policy issues.

Russia’s Asia Pivot

During 2017, Russia sought to ensure that it does not become completely marginalized from another major security crisis, namely North Korea. Unlike in Syria, Russia is clearly a second-order player, as compared with the US, China, South Korea or Japan. Nonetheless, Moscow has tried to position itself as a moderating and pacifying influence, at the same time as most closely aligning its position with China. For example, at a news conference after the September BRICS Summit in Xiamen and in the wake of North Korea’s sixth missile test, Putin adopted a moderating tone noting that “ramping up military hysteria in such conditions is senseless; it’s a dead end […]”. Before posing and answering a question: “What can restore their security? The restoration of international law.”

Similarly in response to the North Korean missile test on 14th of September, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov described their leaders as “hotheads”, who needed to “calm down”. Lavrov also outlined that: “together with China we’ll continue to strive for a reasonable approach and not an emotional one like when children in a kindergarten start fighting and no-one can stop them”. This alignment with China, for example by issuing joint statements on North Korea’s nuclear testing, is intended to bolster Russia’s position within the political negotiation on the crisis.

Russia’s attempts to further diversify its relations and reduce its overreliance on the West continued apace in 2017, with much of the focus on what Lukonin calls its ‘Eastern policy’. In the main, this has centered on bolstering bilateral relations with China. In political, economic and military terms, both Moscow and Beijing have sought to emphasize their ongoing good relations. Xi was treated to a state visit to Russia in July, in which he emphasized that China and Russia are “good neighbors, good friends, and good partners”. In addition, the two sides signed a joint plan in June for military cooperation in 2017–2020, and conducted joint Naval Exercises in the Baltic sea in July and in the sea of Japan in September, together with military exercises in December. Russia is also set to deliver S-400 surface-to-air missile defense systems to China in 2018.

Undoubtedly, Russia is increasingly the junior partner in the relationship, particularly when it comes to trade and economics. Yet, for now at least, the Russian leadership seems to accept this state of affairs. Nonetheless, analysts continue to raise concerns about the increasing asymmetry, divergence and sustainability of this alliance in the long-term. As Niklas Swanström suggests, even if current relations are stable in the shortterm, longer-term prospects are ‘for storms’, notably with regard to the growing sinicization of Central Asia. Crucially, it also remains to be seen how far the dialogue about coordinating the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union and the China’s Belt & Road Initiative will lead to an understanding that is satisfactory to all parties concerned.

More broadly, Russia’s wider Eastern policy bore mixed results in 2017, with short-term gains masking potential longer-term problems. Whilst on the one hand the expansion of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to include Pakistan and India marked a new departure for the organization, this expansion has left the focus, priorities and relevance of this now pan-Asian multilateral framework much less clear. Similarly, there was ongoing cooperation between Russia and India on defense and joint military exercises, but analysts have noted an ever more competitive dynamic within the relationship. This has been fueled by the increasing economic disparity between the two powers. Uncertainty also characterizes Russia’s relationship with Japan, due to ongoing intransigence over the Kuril islands. Although Japan adopted a ‘new approach’ to the dispute, until now it has not borne any fruit, except for bilateral meetings on the sidelines of G20 and Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Russia in September. The talks of a potential rapprochement between the two sides have been complicated by Russia’s decision to designate the islands as a priority development zone, undermining any prospects of joint cooperation on this issue or Japanese firms being allowed to operate on the islands. In addition, Russia has also continued to raise its concerns about the deployment of American missile-defense systems in South Korea and Japan.

Overall, Russia’s Eastern policy continues to be a very mixed bag of short term gains, but with continued question marks hanging over the future direction of key relationships. This is of significance not only for these respective relationships, but it is also potentially problematic for the associated goal of diversifying Russian foreign policy away from a fractious relationship with the West and towards Asia.

Regional Dynamics

2017 saw no breakthroughs in the Ukraine crisis. The relationship between Moscow and Kiev remain in a perilous state. The Minsk process remains stalled and military confrontation in Eastern Donbass continues, amid repeated breakdowns in ceasefire talks. While the wider political negotiations have not progressed. The Ukraine crisis remains a major source of tension between Russia and its Western counterparts. This could be seen in the EU’s decision to continue its sanctions regime against Russia and the passing of an agreement in the US to provide Ukraine with lethal weapons.

Although the idea of placing UN peacekeepers along the conflict lines was floated in September and a major prisoner exchange took place in December, nothing has changed in practice. There is little sense the Kremlin has a strategy to extricate itself from the now intractable crisis, particularly now that Ukraine has passed a reintegration bill that labels Russia as an aggressor state. Despite denouncing the bill as undermining the Minsk II accord, the stalemate is becoming a liability for Russia. Indeed, the Ukraine crisis suggests that whilst the Putin regime may be adept at tactical and short term pragmatic victories, it often lacks suitable strategic solutions for crisis resolution in the long-term. Although time will tell if it is successful, Moscow does seem to have a strategy to extricate Russia from the Syrian conflict. However, in Ukraine, the Putin regime seems to have no such strategy, exposing its lack of longer-term strategic thinking.

Undoubtedly, Ukraine remains the key issue for Russian policy in the post-Soviet space. Among the other priorities, Trenin has noted that most focus is currently on Belarus and Kazakhstan, Moscow’s closest regional partners. The ZAPAD 2017 military exercises in September were indicative of this focus. The Putin regime continued to emphasize the development of the Eurasian Economic Union, and continued to discuss the future prospects of creating a common energy market, a single Eurasian sky program, and ongoing talks regarding the signing of free trade agreements with actors such as ASEAN and Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, Singapore, and Serbia and the potential of an economic-trade agreement with China. However, with little change in Russian economy’s performance, the decline in the momentum of the project continued in 2017.

Conclusion

In summarizing all of the above, Russia’s foreign policy during 2017 can be characterized by a focus on acquiring short-term gains from its role in ongoing international crises, whilst remaining open to new opportunities for increasing its influence in regions further afield. Russia has continued to work to increase its relevance across a divergent set of relations regions (Europe, Middle East, East Asia, South Asia), at the same time as seeking to turn individual security crises to its advantage. Nonetheless, despite its symbolic image as a major threat to the West, Russia remains a second tier player on the world stage. In recognition of this, the Putin regime adopts a pragmatic and flexible approach. Indeed, when it comes to crisis-politics, Russia can still play a major role on the world stage and impact on how these crises unfold. However, the extent to which Russia will be able to implement a robust and concerted policy across such a diverse set of relationships over the long-term remains unclear.

About the Author

Aglaya Snetkov is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies, ETH Zürich and editor of the Russian Analytical Digest. Her main research interests are in Russian foreign and security policies and critical international relations theory.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.