The Effects of Sanctions and Counter-Sanctions on EU-Russian Trade Flows

8 Jul 2016

By Daniel Gros and Federica Mustilli for Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCentre for European Poilcy Studies (CEPS)call_made on 5 July 2016.

After Russia annexed Crimea in early 2014 and then intervened, manu militari, in the Eastern part of Ukraine, the European Union wanted to show its disapproval and put pressure on Russia to change its behaviour. A wide variety of measures were taken, including the imposition of individual restrictions, such as asset freezes and travel bans, but also the suspension of development loans from the EBRD. But the EU (together with the United States) also took, in July and September 2014, a set of broader measures: limited access to EU primary and secondary capital markets for targeted Russian financial institutions and energy and defence companies; export and import bans on trade in arms; an export ban for dual-use goods and reduction of Russia’s access to sensitive technologies and services linked to oil production.[1]

In response, Russia boycotted imported perishable goods and some raw materials (meat, fish and vegetables) from the countries that had imposed sanctions. This set of measures is what is commonly called the economic sanctions (and Russian counter-sanctions). On the EU side, they have been extended at regular intervals and the restrictive measures were again extended until 23 June 2017, when discussed by the European Council on June 28th.[2]

The purpose of economic sanctions is first of all to signal international disapproval with respect to certain specific policies and eventually force the targeted country to reverse them. Historically, we have learnt that only in one-third of the cases have sanctions actually succeeded, which is defined as the sanctions in place actually contributing the desired policy change. Not surprisingly the success (rate) of sanctions is largely influenced by the economic importance of the country that imposes them.[3] Our contribution, however, does not deal with the likely success of European sanctions even if we realise that extending the sanctions can damage diplomatic relations between the EU and Russia. Our purpose here is only to measure their impact on trade flows.

According to a study by the Austrian Institute of Economic Research,[4] the strong fall in exports from the EU to Russia was due, at least partially, to the imposition of sanctions and counter sanctions. The authors argue that sanctions and counter-sanctions have a relative low direct impact on the trade flows of targeted products (especially because some of the contracts have been signed before the imposition of sanctions and thus are exempted). But they also found that the potential trade loss in terms of value added (€34 billion in the short run and €92 billion in the long-run) and employment were attributable to deterioration in trade relations that extended sanctions can exacerbate. That study (inter others) thus concludes that the sanctions have had serious consequences on employment in the EU.

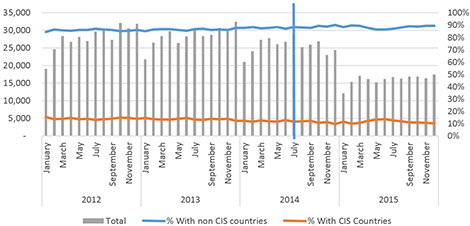

In our view, the key to measuring the impact of the sanctions is to distinguish the effects of economic sanctions on trade flows from the effects caused by the very severe downturn that is hitting Russian economy. Indeed, Russian imports in general have declined (see Figure 1) as the Russian economy went into recession in 2014-05, mostly because of the decline in the price of oil, thus undermining export revenues.

There exists a simple way to disentangle the impact on bilateral merchandise trade of the recession, on the one hand, and EU sanctions (plus counter sanctions), on the other: one has to look only at the share of the EU (and other countries that imposed sanctions, like the US and Japan,) in Russian imports. If these shares have not changed significantly, sanctions cannot be said to have played a major role in undermining trade flows between the EU and Russia.

Figure 2 shows already that the share of non-CIS countries in Russian imports does not seem to have been affected by the sanctions.

As an aside, we note that the share of CIS countries in Russian imports has not increased over the last four years. This suggests that the creation of the Eurasian Economic Union (Russia’s key economic project) has not had a visible impact on trade flows, at least so far.

Figure 1. Montly Russian imports ($ mil, % of importing counrties on right axis)

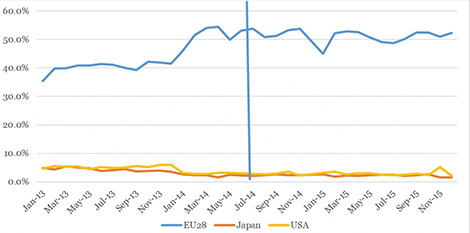

To go into more detail, Figure 2 shows the monthly values of Russian goods imported from EU member states, the US and Japan compared to total Russian goods imported.

The view that the sanctions had a strong impact on trade would imply that the share of the EU in overall Russian imports has declined. We find, however, that since the EU first began the imposition of sanctions, the share of imports from EU member states has remained on average pretty stable (at around 50% of the overall goods imported) until the end of 2015. The shares of imports from Japan and the US started to decrease in January 2014 and remained stable overall (at around 3%) for the two years. The role of those two economies in Russian trade is, however, much lower than that of the EU.

The purpose of this contribution was only to investigate the impact of the sanctions on trade flows – and thus their economic costs to the EU. The result is simple and clear: the fact that the share of EU countries in Russian imports has been stable indicates that the impact of the sanctions on trade flows has been minimal. The observed fall in exports from the EU to Russia was entirely due to the recession in Russia.

The key problem in measuring the impact of EU sanctions is that their onset coincided with the fall of oil prices and a recession in Russia. The political opposition to the sanctions has often been based on the simple observation that “EU exports to Russia have fallen a lot since the sanctions” (often up to 40%), implying that the sanctions have been very costly. Our simple approach suggests that this reasoning is completely wrong. The economic cost of the sanctions has been close to zero, at least in terms of foregone exports from the EU.

It is of course possible that the sanctions had a considerable negative impact on the Russian economy. But that is a different issue. The trade data tell us only that EU exporters cannot complain of facing specific disadvantages in the Russian markets that one can impute to the sanctions.

Figure 2. Monthly Russian imports by partner countries (% of total)

[1] See external pagewww.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions/ukraine-crisis/call_made

[3] Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J. Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott and Barbara Oegg, Economic Sanctions Reconsidered, ’3rd edition, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington,, D.C., June 2009.

[4] E. Christensen, O. Fritz and G. Streicher , “Effects of the EU-Russia Economic Sanctions on Value Added and Employment in the European Union and Switzerland”, WIFO Study, Austrian Institute of Economic Research, Vienna, July, 2015.

About the Authors

Daniel Gros is Director of the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS). He has worked for the International Monetary Fund, and served as an economic adviser to the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the French prime minister and finance minister.

Federica Mustilli is a Research Fellow at CEPS.