Aid Agencies’ Use of Big Data in Human-Centred Design for Monitoring and Evaluation

26 Jul 2016

By Olivier Mukarji for Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageGeneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP)call_made in June 2016.

Addressing the issue of how aid agencies can combine the latest insight in the fields of Big Data and monitoring and evaluation (M&E).

Key Points

- The implications of the emerging trend in the fields of Big Data and M&E in terms of which decision-makers are increasingly told to listen to the data so as to make informed choices based on the outputs of complex algorithms. When the data are about people – especially those who lack a voice – these algorithms run the risk of doing more harm than good.

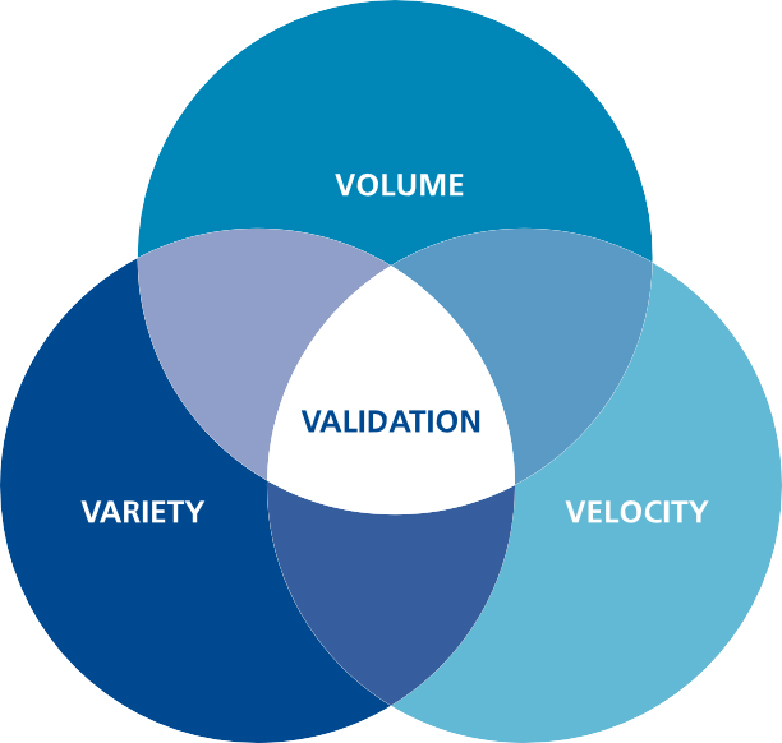

- There are two key concepts deemed necessary for Big Data-enabled M&E approaches - Validation and human-centered design (HCD).

- Newly emerging technological insights have the potential to convert huge numbers of beneficiaries’ views and reactions into a meaningful and shared narrative that provides actionable insights into what works, what does not, and why.

This paper examines some of the ways that Big Data can be used to strengthen M&E in fragile contexts characterized by low-level recurring conflict and mistrust among disparate population groups, governments and even development organizations.

The paper argues that both M&E and Big Data approaches face structural deficits related to a lack of focus on the end user or beneficiary. Unchecked, there is a danger that this will further exacerbate the levels of mistrust in fragile contexts. Any attempt to enhance M&E with Big Data approaches will therefore require a stronger focus on beneficiary validation through feedback loops that consistently secure beneficiaries’ participation. To be of use in fragile contexts, Big Data approaches need to help M&E try to recapture the essential element that is being lost between organizations and governments working in fragile contexts and the beneficiaries of their work, i.e. trust.

The paper introduces two key concepts deemed necessary for Big Data-enabled M&E approaches. The first is validation, which consists of issues such as the methodology and process of data collection; the decisions informed by the latter; and the consequences that involve ethical issues like bias, security, misuse and falsification. The proliferation of development actors churning out information based on myriad different perspectives coupled with the views of disparate groups that these actors are aiming to help continues to confound efforts to find lasting peace in conflict-prone contexts.

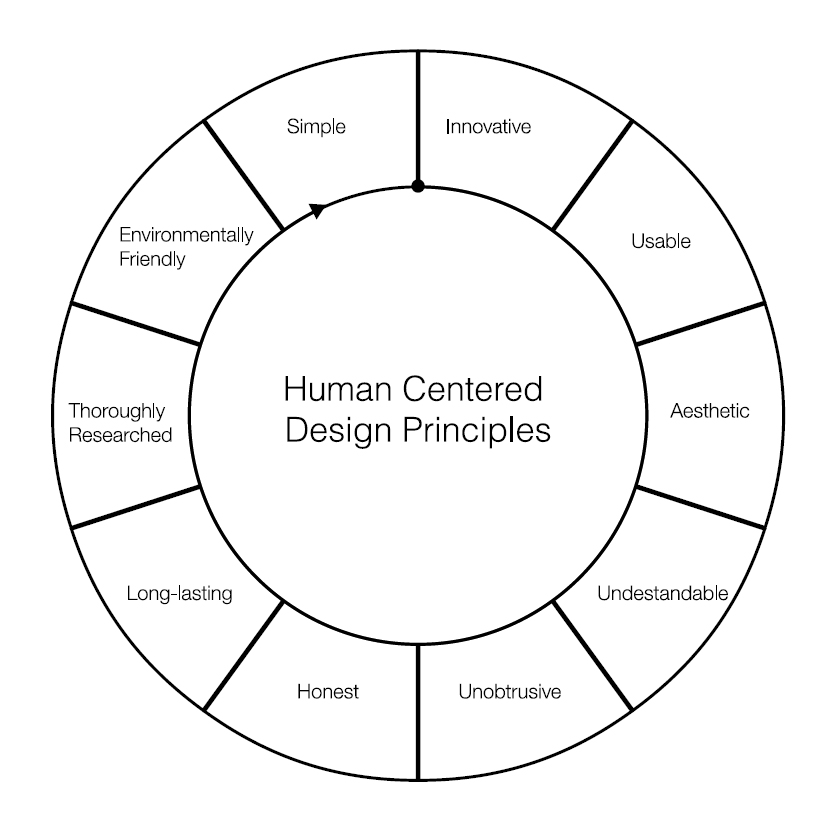

The second concept is that of human-centred design (HCD) and how it can be applied to Big Data and M&E. HCD is intrinsically linked to validation, because its people-centred focus emphasizes the role of the people that should benefit from development initiatives. One of the key strengths of HCD is the active involvement of end users. Different end users validate their situation in different ways, each from their own perspective, including individual beneficiaries, beneficiary communities or even the organizations aiming to help. A focus on end users is crucial, because they know about the context in which the M&E system will be used. Such a focus on end users’ perspectives and their active integration into the M&E system enhances acceptance of and commitment to the process and its content.

Indeed, a Big Data-enabled and human-centred approach to M&E in fragile contexts with a focus on feedback loops should be viewed as an opportunity to keep one ear open to the beneficiaries and organizations seeking to help, and the other to the projects being conceptualized, in a way that dramatically alters how such projects are designed, implemented and scaled. If this were to happen, it would not just be refreshing, but much needed and potentially game changing.

1 Background

More than ever, aid agencies are part of a larger jigsaw of partners, donors and beneficiaries, each with their own perspective that needs to be taken into account in a shifting landscape of risks and opportunities. These multiple perspectives result in myriad approaches to the issue of how to deal with these risks and opportunities, ranging from data gathering to analysis. As a result, there is a proliferation of competing narratives in fragile contexts already characterized by low levels of trust. Monitoring and evaluation (M&E) in situations of conflict and fragility is an emerging and continually developing field of practice. M&E is understood as enabling organizations involved in programme implementation to learn from experience, achieve better results and be more accountable. For a number of reasons, M&E is often neglected in conflict-affected and fragile situations. In insecure and volatile contexts programme objectives and activities are often fluid, making it difficult to maintain a coherent approach to M&E.

Technological advances in the areas of data collection and use, broadly termed Big Data, present many opportunities for M&E. Big Data is an evolving term that describes any voluminous amount of structured, semi-structured and unstructured data that has the potential to be mined for information. Big Data is understood as an evolving term that describes how organizations can enhance M&E through technological insights used to increase the volume, variety, and velocity of structured, semi-structured and unstructured data.1

In spite of progress toward establishing and building M&E best practices, the process of overcoming the key conceptual and practical challenges continues to stymie collective efforts to assess impact. To date, there is no systematic way of collecting and analysing information in real time, let alone in a way that ensures that all the beneficiaries and other stakeholders are on board from the design phase through to the implementation phase in order to build trust through ownership and participation. Additionally, it has become increasingly clear that multiple approaches that compartmentalize short-term output-centric perspectives hamstring efforts to track and assess collective long-term impact.

1 Challenges facing M&E and Big Data

At the core of M&E in fragile contexts is the ability to identify, collect, and process data to enable more informed decision-making. But in fragile contexts where dynamics are constantly evolving, ensuring that the right information is being collected in a timely way from multiple sources remains a persistent challenge, despite its being essential to ensuring a collective response. In spite of growing pressures to be more accountable and efficient, M&E capacities arguably range from average to low levels of basic skills2 as a result of shrinking budgets3 and high staff turnover.4

Big Data-enabled M&E approaches face four key challenges in fragile contexts. These are discussed below.

Low data volumes

The overall volume of data available in many fragile contexts is low due to limited data-collecting capacities and lack of access. M&E usually resorts to data that is limited in scope and completeness and hard to cross check5, particularly baseline studies.6 When it exists, data is often segmented and not shared, because actors tend to work in separated silos of information – both among and within organisations.7 Data volume is often determined by lack of data sharing and is restricted, since organisations and corporations tend not to share much of the valuable data they possess. The reluctance of these entities – in both the private and public sectors – to share data constitutes a major hurdle and will continue to require active engagement from both public and private actors if it is to be addressed.8 This challenging climate of non-cooperation among agencies is not only due to competition for donor funds, but is also a result of high staff turnover, low prioritisation of M&E and under-developed cross-institutional information management systems. Together, these structural factors continue to create and sustain silo projects.

Lack of data source variety

Organisations have a limited variety of options to compensate for this data scarcity: they usually respond by undertaking unilateral and costly assessments and surveys9 that may themselves be subject to entry/reporting delays and errors, and which may incur additional scrutiny costs; or they may take decisions based on less authoritative and reliable sources.10 In fragile contexts this is further compounded by the fact that although mobile phone and internet penetration are generally expanding rapidly, huge infrastructure connectivity gaps remain, which makes it even harder to secure the participation of at-risk population groups.

Outdated data

The data collected in rapidly changing fragile contexts are often already outdated even in the analysis phase. Rigorous longitudinal studies can seldom be undertaken due to the difficulties inherent in conducting research in these contexts. By design, M&E is focused on the past and is relegated to identifying what has happened and outlining what worked and what did not.

The focus is on reporting on processes and activities rather than the perspectives of those whose lives are shaped by the results of these interventions. All too often M&E reports are delivered too late to have an effect on project implementation. Too few people read such reports due to high staff turnover and the lack of a shared information management system. More importantly, there is no feed back to staff in the project area. No funds are available for dissemination and staff have moved on, so lessons learned are written down but rarely absorbed.

Lack of validation

Due to the low levels of trust and implementation capacity among national and international actors, as well as multiple myopic perspectives, a shared narrative and vision of the future remain elusive – especially at the operational level. The use of more and multiple data sources in M&E is neither straightforward nor always appropriate, and raises a number of questions. For instance, what of these sources’ validity: What do we wish to measure? How do we collect information? Whom should we involve? With Big Data, the challenge is framed the other way round: What data do we have? What can we do with it? Can it be used by the project implementers on the ground, beneficiaries and other stakeholders? As various data sources are accessed and analysed, they ultimately reflect the interests of those who are part of this data collection, query and analysis process. Data sets are often analysed from the perspective of those who collect the data, but not from the perspective of the people who depend on the results. Indeed, as a result of a general lack of feedback mechanisms, beneficiaries and other local stakeholders often have little understanding of why data is being collected in the first place, nor how it is being used.

This augments the already low levels of trust between aid agencies and recipients and is aptly captured by a traditional North Kivu proverb, “what you do for me, but without me, is against me”.11 The fact that we cannot know in advance what use will be made of our private data poses an ethical problem in a developed world context. But in a fragile context where levels of trust among communities and between state and communities are already low and state capacities poor at best, getting it wrong can have grave consequences. For better or worse, do-no-harm principles and other social and environmental safeguard mechanisms are an important first step in informing ethical considerations, as well as a guide for the decision-making and actions of actors working in development and fragile contexts.12 Although the subject of ethics in the field of Big Data is relatively new, it has rapidly gained traction recently, as evidenced by Edward Snowden’s revelations about the US National Security Agency surveillance programme and Apple’s dispute with the FBI over the latter’s right to access encrypted data on phones. The innovative use of data and data-gathering techniques will continue to create tensions related to privacy and data protection as legislation attempts to catch up with what is happening on the ground.

2 Human-centred approach to Big Data-enabled M&E

Key to a human-centred approach is that it addresses the key structural challenge facing M&E and Big Data: validation. At its core is a focus on people. This is achieved via interviews, observation and good old-fashioned listening.13 Conversations must shift from competing narratives based on past reflections and performance to a shared narrative about the future based on frequent conversations in the present. With principles like innovation, usability and unobtrusiveness, human-centred design (HCD) offers methods and techniques to strengthen existing methodologies and technologies in order to secure the stories and perspectives of people and communities. HCD champions learning and utility through the investigation of social problems, analysis of knowledge, engagement of users and iteration of solutions.

Dieter Rams sums it up well: “In my eyes, indifference towards people and the lives they lead is the only sin a designer can commit.” Placing a stronger emphasis on HCD and its focus on value and usability has many benefits to offer in terms of offsetting the inherent challenges facing M&E and Big Data, namely the issue of validity. Unsurprisingly, together with Big Data has come a host of new disciplines and stakeholders that are all keen to ensure sustainable progress in fragile contexts. Nevertheless, collaboration among practitioners, social scientists and data scientists will need to include beneficiary participation to make progress in contexts where there are multiple perspectives on truth. HCD is a collaborative process that benefits from the active involvement of various parties, all of whom have insights and expertise to share.

It is therefore important that the development team be made up of experts with technical skills and people with a stake in the proposed M&E process. The ideal and most effective team would include managers, design specialists, beneficiaries, software engineers, graphic designers, interaction designers, project staff and thematic practitioners familiar with the contextual realities.

With this shift towards large-scale quantitative approaches to data collection and analysis, the continued importance of qualitative techniques is a must for two reasons: firstly, because there is a risk of losing the compelling and inspiring stories of people in what ultimately becomes yet another homogenized narrative of data at a scale that does not address underlying trust issues; and secondly, because, as evidenced in fragile contexts, sidelining people’s stories and perspectives is a guaranteed way of ensuring that projects fail.

3 Volume, variety, velocity and validation

Big Data are often characterised by the so-called 3Vs: volume of data, variety of types of data and the velocity at which the data is processed.14 However, in fragile contexts it is becoming increasingly clear that the one common challenge facing both M&E and Big Data is that of validation. A process that ensures the validation of data by the users who are affected by the data that has been collected and analysed is key. Validation should therefore be the fourth aspect of any Big Data approach to enhancing existing M&E methodologies. This is crucial, since merely injecting more data into a context where there is no trust will only give people more issues to contest and on which to disagree. Validation can be operationalised using a human-centred approach when data volumes, variety and velocity increase in M&E.

Volume

This relates to the unprecedented amount of data that can be collected, whether currently or in the future.15 Consequently, new proxy indicators can be created that allow for a deeper level of analysis16 – and eventually a more nuanced picture of at-risk populations.17

Variety

This relates to the formal and content heterogeneity of datasets. Technological innovations increasingly permit access to datasets that are both diverse and produced by a variety of sources (radio, phone, internet, etc.);18 some of these datasets are more easily collected than others. This can contribute to addressing data gaps and issues related to accessibility, as well as enabling the validation of existing datasets. Big Data approaches can improve the cost efficiency of M&E and facilitate consensus building by connecting datasets. New ways of potentially breaking down silos by linking datasets are starting to play an increasing role in generating new insights, while creative approaches to visualising data can help to generate a shared narrative among various stakeholders. To match this new potential, organisations are starting to develop in-house capacities and establish partnerships and joint operations with partners to access and manage data in order to leverage the potential of increased data volumes, variety and velocity.

Velocity

There has been a dramatic increase in the rate at which data from multiple sources is being collected and the speed at which it is processed and acted on. This has one key benefit: a reduction in the time it takes to collect and analyse data and act on it. There is also a potential to increase the capacity for real-time analysis and thus be more responsive to events unfolding on the ground.19

Validation

If people and organisations are expected to be responsible for their own transformation then their perspectives need to be taken into account at all times. Organisations increasingly acknowledge the importance of improving the validity of data, and a stronger and context-specific integration of research methodologies could strengthen the validity of the data collected while simultaneously increasing the volume, variety, and velocity of data collection and use.20

EXAMPLES OF HOW TO INCREASE VALIDITY

Volume: using new sources of data to monitor risks

New sources of Big Data can facilitate innovative solutions to compensate for the difficulties of hazard detection and mapping in data-scarce environments. The US Geological Survey, for example, integrates social media surveillance into its network of seismographs to improve the tracking and real-time mapping of landslides and earthquakes. The case study “Early Flood Detection for Rapid Humanitarian Response: Harnessing Big Data from Near Real-time Satellite and Twitter Signals” provides an example of how social media can be used to gather real-time images and descriptions of developing situations.

Variety: Analysing large-scale news media content for early warning of conflict

Global Pulse and the UN Development Programme explored how the data mining of large-scale online news data could complement existing tools and information used for conflict analysis and early warning. Taking Tunisia as a test case and analysing news media archives from the period immediately prior to and following the January 2011 government transition, the study showed how tracking changes in tone and sentiment in news articles over time could offer insights about emerging conflicts. This study indicated the considerable possibilities for further explorations of how the mining of online digital content can be leveraged for conflict prevention. Human-centred approach in the making: TrackFM (Trackfm.org)

Through a network of local, regional and/or national broadcasters (radio, TV and print), TrackFM reaches those segments of the population that are often excluded from public debate and M&E exercises. In order to gather these relevant “voices from the field” in hard-to-reach areas, TrackFM facilitates and mediates collaborations between practitioners and radio stations, collecting research questions from non-profit organizations while simultaneously training radio hosts to integrate the questions into their talk shows as radio polls. The TrackFM software allows listeners to send feedback via mobile messaging services free of charge. SMS responses from radio listeners are collected through the software and instantly integrated into a range of comprehensive graphs and maps for the radio host’s use.

Velocity: understanding public perceptions of immunization using social media

Pulse Lab Jakarta undertook a project to examine how an analysis of social media data could be used to understand public perceptions of immunization. In collaboration with national counterparts, it filtered tweets for relevant conversations about vaccines and immunization. Findings included the identification of perception trends, including concerns around religious issues, disease outbreaks, side effects and the launch of a new vaccine. The results confirmed that real-time information derived from social media conversations could complement existing knowledge of public opinion and lead to faster and more effective responses to misinformation, since rumours are often spread through social networks.

4 Conclusion: towards a common narrative

It is becoming increasingly clear that the common challenge facing both M&E and Big Data is the issue of validation. A process that ensures the validation of data by the users who are affected by the data that is collected and analysed is key. This is an important issue when increasing the volume, velocity, and variety of data sources collected and analysed so as to ensure a convergence of multiple perspectives to create a shared narrative. Indeed, with the growing emphasis on impact measurement, organizations are increasingly obliged to work closer together to assess collective progress in a way that goes beyond merely measuring the outputs of individual projects. No longer can a single entity, whether public or private, achieve its objectives on its own, no matter how big it is or how much funding it has. In this environment, finding ways to track progress, institutionalize learning and champion a shared narrative has never been more important.

It is clear that Big Data-enabled M&E has the potential to improve lives. But without a human focus, its single-minded efficiency can accentuate structural weaknesses inherent to Big Data and M&E, thereby further marginalizing people who are already at risk.

An emphasis on validation through a human-centred approach to M&E is an iterative process. It will require a strong emphasis on ethics, transparency, privacy and security to offset the risks associated with the use of Big Data in fragile contexts. How do M&E and the data it collects and uses relate to the people whom aid organizations are trying to help? How much of this decision is simply machine generated and how much is beneficiary focused? One thing is certain: keeping people in the loop is a time-tested recipe to build trust, offset risk and create opportunities.

Recommendations

- Championing human-centred design processes. This will help simplify and validate complex systems such as M&E through the use of Big Data approaches as enablers. By involving beneficiaries from the outset and throughout the implementation period, the process will focus on the validation and utility of the results, as well as forging trust. This will help make organizations collectively more accountable for what happens as a result of their work (impact), and means being accountable for more than simply whether the organization has achieved its immediate objectives.

- Storytelling. Adopting a storytelling approach to M&E that puts the protagonist beneficiaries at the centre will help shift the focus of development actors away from the formulaic, public-relations narratives that many organizations use in which those on the receiving end of aid are passive characters in the story.

- Transparency. Any M&E system will need to explain and show how (and by whom) information will be collected, analysed, and reported to and discussed with stakeholders. Each decision will need to be explained and documented in relation to stakeholders, outcomes, indicators and benchmarks.

- Iterative and interactive process. Mechanisms should be in place for providing feedback to and receiving it from end users at regular intervals after their use and experience of early design solutions. The feedback from this exercise should be used to develop the design further. Technology allows stories not merely to become interactive, but also to reach new audiences.

- Ethics. Dialogue on ethics and privacy should be fostered with and among stakeholders to understand and address the social, political and legal risks of an intervention.

- New types of partnerships. New partnerships are needed with a focus on public- private-individual partnerships that bring together multidisciplinary teams in a human-centred design process to advance the use of Big Data and M&E to serve populations at risk in fragile contexts.

Notes

1 This comes from the seminal work by D. Laney, “3D Data Management: Controlling Data Volume, Velocity and Variety”, MetaGroup Online Report, 2001, <http://blogs.gartner.com/doug-laney/files/2012/01/ad949-3D-Data-Management-Controlling-Data-Volume-Velocity-and-Variety.pdf>

2 M. Kawano-Chiu, “Starting on the Same Page: A Lessons Report from the Peace-building Evaluation Project,” 2011, p. 8,

<http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.allianceforpeacebuilding.org/resource/collection/9DFBB4C8-ABB-4A5B84600310C54FB3D9/

Alliance_for_Peacebuilding_Peacebuilding_Evaluation_Project_ Lessons_Report_June2011_FINAL.pdf>..

3 L. Raftree, and M. Bamberger, “Emerging Opportunities, Monitoring and Evaluation in a Tech-enabled World”, Discussion Paper, Rockefeller Foundation, 2014, <https://assets.rockefellerfoundation.org/app/uploads/20150911122413/Monitoring-and-Evaluation-in-a-Tech-Enabled-World.pdf>.

4 C. Scharbatke-Church, “Evaluating Peacebuilding: Not Yet All It Could Be”, in M. F. B. Austin (ed.), Advancing Conflict Transformation, Opladen/Farmington Hills, Barbara Budrich Publishers, 2011; D. Stauffacher, B. Weekes, U. Gasser, & C. Maday, “Peacebuilding in the Information Age: Sifting Hype from Reality”, 2011, available at: <http://www.crowdsourcing.org/document/peacebuilding-in-the-information-age-sifting-hypefrom-reality/2275>; and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), “Monitoring & Evaluation in Post Conflict Settings”,2006, <http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADG193.pdf>.

5 S. Köoltzow, 2012, “Monitoring and Evaluation for Peacebuilding”, Geneva Peace-building Platform, Paper no. 9, 2012, <http://www.gpplatform.ch/sites/default/files/PP%2009%20-%20Monitoring%20and%20Evaluation%20of%20Peacebuilding%20 The%20Role%20of%20New%20Media%20-%20Sep%202013.pdf>.

6 C. Scharbatke-Church, 2011.

7 S. Köoltzow, 2012.

8 United Nations Global Pulse, “Big Data for Development”, White Paper, 2012, p 25, <http://www.unglobalpulse.org/projects/BigDataforDevelopment>.

9 United States Agency for International Development (USAID), “Monitoring & Evaluation in Post Conflict Settings”, 2006, <http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/PNADG193.pdf>.

10 S.E. Stave, “Measuring Peacebuilding: Challenges, Tools, Actions”, Oslo, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre, 2011.

11 Proverb repeated to Oxfam by an old man in North Kivu: “‘For Me, But Without Me, Is Against Me’: Why Efforts to Stabilize the Democratic Republic of Congo Are Not Working”, Oxfam Lobby Briefing, July 2012.

12 P. Meier, Digital Humanitarians: How Big Data Is Changing the Face of Humanitarian Response, London, CRC Press, 2012, p.182-184.

13 T. Brown and J. Wyatt, “Design Thinking for Social Innovation”, Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2010.

14 D. Laney, 2001.

15 A. Gandomi and M. Haider, “Beyond the Hype: Big Data Concepts, Methods and Analytics”, International Journal of Information Management, Elsevier, Vol.35 (Issue 2), 2015, p.137-144.

16 Department for International Development (DFID), “Big Data for Climate Change and Disaster Resilience: Realising the Benefits for Developing Countries,” Synthesis Report, 2015, <http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/Output/202029/>.

17 World Bank, “Big Data in Action for Development, Online Report”, 2014, <http://data.worldbank.org/news/big-data-in-action-for-development>.

18 A. Gandomi and M. Haider, 2015.

19 Ibid

20 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), “Handbook on Monitoring and Evaluation for Results”, 2002, <http://web.undp.org/evaluation/documents/handbook/me-handbook.pdf>; and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), “Monitoring and Evaluating Empowerment Processes”, 2012, <http://www.oecd.org/dac/povertyreduction/50158246.pdf>.

About the Author

Olivier Mukarji is an Executive-in-Residence Fellow at the Geneva Centre for Security Policy, and founder and CEO of OAM Consult which focuses on integrating human-centred, crowd-based technology into client advisory services for private and public organisations working in fragile contexts.