Russian Analytical Digest No 190: Russia and the Oceans

13 Oct 2016

By Claire Christian and Vitaly Kozyrev for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The two articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 7 October 2016.

Russia and the Southern Polar Regions: Consensus or Conflict?

By Claire Christian

Abstract

A large coalition of countries would like to create a marine protected area for the Ross Sea and East Antarctica. The measures would provide valuable protection for a unique ecosystem and numerous iconic species. In advance of an October meeting of the Commission on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), Russia is the only holdout blocking a consensus decision. Russia has been a constructive player in numerous cases and the hope is that it will join the negotiations.

New Momentum for Protection

Since the beginning of 2015, ocean conservation has reached new heights and made headlines around the globe. In 2015, more of the planet was committed to protection than ever before. From the Pacific nation of Palau, to Chile’s famed Easter Island, New Zealand’s Kermadecs, and the remote British overseas territory of Pitcairn Island, more than 1,609,344 square kilometers of ocean were set aside in marine protected areas (MPAs) or fully protected marine reserves.

The drive to implement MPAs and marine reserves has gained significant momentum in recent years. Scientific research has confirmed that, when properly designed and enforced, MPAs and reserves can have significant conservation benefits and in some cases allow depleted species to recover.1 These areas can also provide scientists with reference zones for studying ecosystems and species in the absence of direct human impacts, which is particularly important in understanding how climate change is affecting the marine environment. Even with recent designations, only two percent of the ocean is fully protected in marine reserves. This is below the 10 percent protection target adopted by the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in its landmark Aichi Targets and far below the 30 percent that scientists have found to be the most effective in achieving protection goals.2

Focusing on the Ross Sea and East Antarctica

Most MPAs and reserves have been designated in territorial waters, but these only make up a fraction of the world’s oceans. In response, the Commission on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), the international, treaty-based organization that governs the Southern Ocean around Antarctica, decided to designate a circumpolar network of MPAs. For several years, the twenty-five member governments of CCAMLR (twenty-four countries and the EU) have met to discuss proposals for MPAs in the Ross Sea (led by the U.S. and New Zealand) and East Antarctica (led by the EU, France, and Australia) respectively, but have yet to reach consensus on their official designation even after holding five formal meetings.

The proposed protected areas together are almost 2.2 million square kilometers in size, an area larger than Greenland. More importantly, they include the habitats of many iconic species, including penguins, whales, seals, and Antarctic toothfish, which is better known to consumers as “Chilean seabass.” Polar waters may appear inhospitable; nevertheless, the Southern Ocean is home to many species that have adapted to thrive in frigid temperatures. This includes the Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba), a tiny, shrimp-like crustacean that is thought to be one of the most numerous on Earth and is eaten by everything from starfish to blue whales.

Although fishing is increasing and waters are warming and acidifying, the Southern Ocean still remains relatively untouched by human impacts, and scientists have identified the Ross Sea as one of the least altered marine ecosystems on Earth.3 East Antarctica is home to breeding habitats for seals, penguins and flying birds, and has unique geographic features. The countries that have proposed the East Antarctica and Ross Sea MPAs have expended considerable effort to analyze available scientific information and develop areas for protection that will not only safeguard the ecology of these regions, but also provide opportunities for research on topics

ranging from climate change to fish populations.

Russia Opposes MPAs

In October 2016, CCAMLR will meet again to decide whether to make these proposed MPAs a reality. The areas covered by these MPAs would restrict fishing—in the Ross Sea by the inclusion of no-take zones, and in the East Antarctic by requiring all fishing activity to go through an approval process. The restrictions will not affect current fishing levels in these regions. Moreover, the data collection and scientific research that are integral components of managing all MPAs can actually help inform management of fisheries (including that of toothfish). They also help CCAMLR fulfill some of its main obligations: to set appropriate catch limits and minimize ecosystem impacts. Not all CCAMLR Members supported the MPAs initially, and some expressed reservations about restricting fishing opportunities. But these concerns have been addressed and 24 governments have indicated that they are satisfied with the revisions. But only one country, Russia, continues to prevent consensus and oppose MPAs.

It has proven difficult to determine how to address Russia’s opposition. Tensions between Russia and other countries over a variety of other issues such as Crimea and Syria may be partly to blame. This article will focus on CCAMLR-specific issues. Some of the tension reflects larger disagreements among CCAMLR members about the meaning of the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention). Article II of the Convention states:

• 1. The objective of this Convention is the conservation of Antarctic marine living resources.

• 2. For the purposes of this Convention, the term “conservation” includes rational use.4

• 3. Any harvesting and associated activities in the area to which this Convention applies shall be conducted in accordance with the provisions of this Convention and with the following principles of conservation: a) prevention of decrease in the size of any harvested population to levels below those which ensure its stable recruitment. For this purpose its size should not be allowed to fall below a level close to that which ensures the greatest net annual increment; (b) maintenance of the ecological relationships between harvested, dependent and related populations of Antarctic marine living resources and the restoration of depleted populations to the levels defined in sub-paragraph (a) above; and (c) prevention of changes or minimisation of the risk of changes in the marine ecosystem which are not potentially reversible over two or three decades, taking into account the state of available knowledge of the direct and indirect impact of harvesting, the effect of the introduction of alien species, the effects of associated activities on the marine ecosystem and of the effects of environmental changes, with the aim of making possible the sustained conservation of Antarctic marine living resources.

A member of the U.S. government delegation who was present during Convention negotiations recalls that Article II was intended to ensure that CCAMLR was “an ecosystem conservation regime, not a regional MSY [maximum sustainable yield] fishery management regime.”5 Fishing, therefore, could only happen if the three principles of conservation described in paragraph 3 of Article II were implemented.6 This was a revolutionary concept in fisheries management when the Convention was signed in 1982, but has become more common in the years since. Since then, it has become apparent that not all CCAMLR members interpret Article II in terms of fisheries conservation.

Some CCAMLR Members, including Russia, have implied that the Convention creates an obligation to gather data and open fisheries. In addition, Russia has argued that creating MPAs with large no-take areas will hinder CCAMLR’s work, since fishing vessels often gather data that is used by CCAMLR to make fisheries management decisions.7 Neither proposed MPA prohibits research fishing, but would place some additional limits on it. Furthermore, commercially viable species represent a small fraction of the marine life in the Southern Ocean. MPAs are designed to conserve whole ecosystems, in line with the foundational principles of Article II, and research plans will likewise need to be broad.

Although fishing vessels do sometimes offer opportunities for scientists doing research on scientific topics unrelated to commercial interests, much important research is sponsored by CCAMLR members and takes place using government research vessels. Fishing vesselbased research is primarily used to inform the development of fish stock assessments that can be used to set catch limits. But the research and monitoring on some objectives not related to commercial species is unlikely to be carried out by fishing vessels. For example, one of the objectives of the Ross Sea MPA is “to protect largescale ecosystem processes responsible for the productivity and functional integrity of the ecosystem.”8 The view that excluding fishing vessels will mean a lack of data thus indicates a narrow interpretation of the purpose of MPAs and of CCAMLR’s work in general.

Securing Access to Fisheries

Russia’s insistence on the need for fishing vessel-based research seems to stem both from a lack of government-funded research (making it necessary to use commercial vessels as a research platform) as well as a desire to secure fishing access to the Southern Ocean. CCAMLR closes areas to fishing for several reasons. In some cases, CCAMLR scientists do not believe they have sufficient information to set appropriate management rules in some areas, either due to a lack of data or due to past overfishing, and close areas until there is the capacity to conduct the right kind of research. Other closed areas are part of an overall scientific strategy for managing fishing in a large area.

CCAMLR’s Scientific Committee and its working groups have analyzed all proposals for research fishing with extra care over the past few years in an effort to ensure that research programs are providing the data required to develop stock assessments and understand ecosystems better. This process has been tense at times, particularly when Russia has presented proposals. Russia has expressed a desire to see more closed areas reopened, and has submitted proposals for research that would ostensibly provide the data needed to do so, including in areas encompassed by the Ross Sea MPA. This research has drawn scrutiny from the CCAMLR Scientific Committee and its working groups. And in recent years, Russian research fishing in the Weddell Sea obtained strikingly anomalous data. CCAMLR has prohibited Russian research in that area until Russia can fully investigate the situation and determine if their research was conducted and reported according to CCAMLR regulations. This has greatly frustrated Russia, which has indicated that it does not accept the scientific reasons given for rejecting its plans.

Another aspect of Russia’s opposition to the Ross Sea MPA is a belief that these protections will impose additional restrictions on a place that already has too many areas where fishing cannot occur. At the 2015 CCAMLR meeting, Russia noted that fishing is already not allowed in 70 percent of the Ross Sea9, and the MPA would limit this area further since it has a large no-take zone. The MPA will not change catch limits, but will constrain fishing grounds slightly. Russia wants to open closed zones in the Ross Sea that are not in the MPA, perhaps with the hopes that doing so would significantly increase the fishable area and catch limit.

However, toothfish catch levels in the Ross Sea are currently informed by a multi-year strategy developed by CCAMLR scientists, and unless there are dramatic increases in toothfish population estimates (which is highly improbable), they are unlikely to change. Over the last two fishing seasons (2013–2014 and 2014–2015), Russia has been one of seven countries fishing in the Ross Sea, and took 12 percent and 17 percent of the catch, respectively. The fishery is an Olympic fishery, meaning that the catch is not allocated between participants but is a race for fish before the catch limit is reached. Thus it appears that Russia’s main opposition to MPAs is not due to diminution of its present fishing ability, but rather due to perceived restrictions on potential new fishing opportunities and possibly precedent, since these MPAs are expected to be followed by others.

Russia has also indicated that it believes MPAs are linked to territorial claims, since some MPAs are located adjacent to land areas claimed by their proponents. New Zealand countered this argument by noting that “’[w]e do not see any advantage for territorial sovereignty claims on the Antarctic continent that would be derived from establishing an MPA...this MPA is about collective decision-making and management.”10 Indeed, the research and monitoring required for the MPAs will require multiple countries’ involvement. However, if Russia can only contribute fishing-vessel based research to the CCAMLR process, it may still believe its influence in CCAMLR will decrease if MPAs are created and more of CCAMLR’s agenda is devoted to MPA-related issues.

Russian Leadership in Other Areas

Even as these disagreements occur in CCAMLR, in other areas of the world, Russia has demonstrated leadership in marine protection. In August 2015, Russia joined with Canada, Denmark, Norway, and the United States to voluntarily ban commercial fishing in the Central Arctic Ocean. In the Arctic, where the country has a long history of exploration, it constructively participated in the meetings and discussions leading to this closure, and has taken an active role in making sure that scientists can learn more about fish stocks and how they are reacting to melting ice, warming waters, and ocean acidification.

Russia has an equally strong connection to the more geographically distant southern polar regions. Russians Admiral Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev, his second-in-command, became the first explorers to set eyes on the Antarctic continent in 1820. Over the years, their legend has grown, and they are remembered as some of the world’s greatest explorers. Since then, Russia has had a robust scientific presence in the Antarctic.

Over the years, many countries have developed a scientific presence in Antarctica. As these countries realized how important and unique Antarctic research had become, a decision was made to develop an international treaty for the continent. In 1959, at the height of the Cold War, the United States, the then-Soviet Union, and 10 other countries with interests in the Antarctic came together to declare the continent a place of peace and science. Today, Antarctica is home to significant research, including climate change studies that can be conducted nowhere else. A subsequent treaty was signed by these countries and others in 1982 to create CCAMLR, which is widely considered one of the first governance organizations to use an ecosystem-based approach to managing activities. Russia, therefore, has a long history of leadership on Antarctic issues, even in a historic, challenging geopolitical climate.

This year, Russia will once again chair the annual CCAMLR meeting. Other CCAMLR members have stated their disappointment with the failure to reach consensus on these MPAs despite agreeing unanimously to create them. Some members are developing proposals for MPAs in other parts of the Southern Ocean and would prefer for the East Antarctic and Ross Sea MPAs to be finalized and designated first. Fulfilling the commitment to a network of MPAs seems unlikely unless Russia and MPA proponents can make progress in their negotiations, and unless CCAMLR members can reach a unified understanding of how to interpret the Convention’s mandate.

Although this may seem like a fairly unpromising situation for achieving international cooperation, it is not without precedent in the Antarctic. In the 1980s, countries party to the Antarctic Treaty spent six years negotiating a new international agreement to regulate mining on the Antarctic continent. Even though mining had not yet occurred, it was thought better to have rules in place before problems emerged. A last-minute change of heart from Australia and France led instead to the negotiation and ratification of the Environment Protocol, which banned mining. Thus, Antarctic Treaty parties were able to agree that it was more prudent to protect the continent than to exploit it.

MPAs in CCAMLR present a similar situation for the Antarctic Treaty System. Antarctic governance has a reputation for being a beacon of international cooperation and policy innovation. This has largely been possible because the countries involved have decided that they have a responsibility to protect Antarctica and cannot only act to protect narrow national interests. The MPA discussion in CCAMLR has tested this reputation and exposed some strong differences of opinion over interpreting the Convention. But these differences have been largely resolved through dialogue and good-faith negotiations. As the annual CCAMLR meeting in October approaches, MPA proponents can only hope that Russia will come to the table in the traditional spirit of polar cooperation.

Notes

1 Graham J Edgar et al., “Global Conservation Outcomes Depend on Marine Protected Areas with Five Key Features.,” Nature 506 (2014): 216–20, doi:10.1038/nature13022; Callum M. Roberts and Julie P. Hawkins, “Establishment of Fish Stock Recovery Areas,” European Parliament (2012), doi:10.2861/50714.

2 Bethan C. O’Leary et al., “Effective Coverage Targets for Ocean Protection,” Conservation Letters 00, no. 0 (2016): 1–6, doi:10.1111/conl.12247.

3 Benjamin S Halpern et al., “A Global Map of Human Impact on Marine Ecosystems.,” Science (New York, N.Y.) 319, no. 5865 (February 15, 2008): 948–952, doi:10.1126/science.1149345.

4 external pagehttps://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/camlr-convention-textcall_made

5 Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition. 2015. Implementing Article II of the CAMLR Convention. CCAMLR XXXIV/BG 25. Available at external pagehttp://www.asoc.org/storage/documents/Meetings/CCAMLR/XXXIV/cc-xxxiv-bg-25.pdfcall_made.

6 Ibid.

7 Scientific Committee for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. 2014. Report of the Thirty-Third Meeting of the Scientific Committee. Hobart, Australia: paragraph 5.38.

8 New Zealand and the United States. 2015. A proposal for the establishment of a Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area. CCAMLR XXXIV/29 Rev. 1. Available at external pagehttps://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/environment/antarctica/ross-sea-region-marine-protected-area-proposal/call_made.

9 Commission on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. 2015. Report of the Thirty-Fourth Meeting of the Commission. Hobart, Australia: paragraph 8.

10 Commission on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources. 2014. Report of the Thirty-Third Meeting of the Commission. Hobart, Australia: paragraph 7.65.

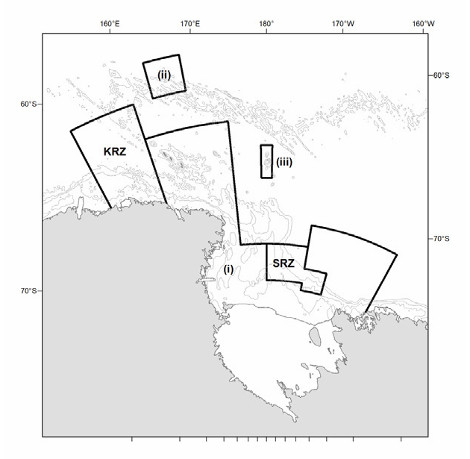

Figure 1: New Zealand–U.S. Proposal for the Ross Sea Marine Protected Area, 2015

Source: A Proposal for the Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area, Delegations of New Zealand and the United States, 25 October 2015, p. 10, <https://www.mfat.govt.nz/assets/_securedfiles/Antarctica/Proposal-for-establishment-of-Ross-Sea-region-MPA-CCAMLR-XXXIV29-Rev1.pdf>. The original caption reads: “The Ross Sea Region Marine Protected Area, including the boundaries of the General Protection Zone, composed of areas (i), (ii), and (iii), and the Special Research Zone (SRZ), and the Krill Research Zone (KRZ). Depth contours are at 500 m, 1500 m, and 2500 m.”

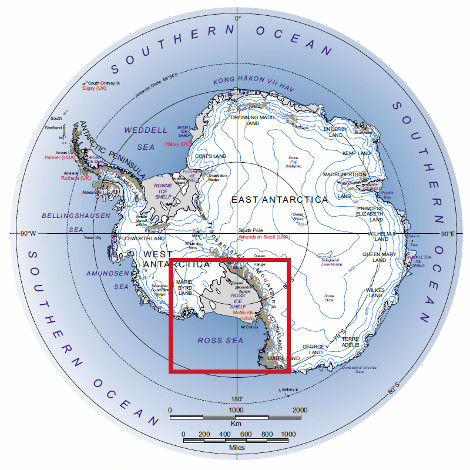

Figure 2: Overview Map of Antarctica

Source: <http://lima.nasa.gov/pdf/A3_overview.pdf>

Does Moscow Cross the Red Line in the South China Sea Dispute?

By Vitaly Kozyrev

Abstract

Despite speculations about Russia’s reluctance to back China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea area, the recent naval exercise “Joint Sea-2016” marked a significant shift in the Kremlin’s posture. While demonstrating an unprecedented level of tactical coherence and interoperability of the two countries’ military forces, the geographical coordinates of maneuvers and the top-level political rhetoric in the Russian leadership around the disputes underline Moscow’s growing support of China on the issues of internationalization of the conflict and freedom of navigation. Moreover, Russia’s changing attitudes toward the issue are increasingly informed by the congruent Russo–Chinese perception of global strategic stability, which equally regards the two countries’ military control over the Crimean peninsula (Russia) and the South China Sea (China) as the restoration of the global balance of power upturned by US unilateral actions and excessive uses of force.

Different Perspectives from West and East

Among the many facets of an ongoing strategic rapprochement between Beijing and Moscow, Russia’s potential role in managing the most sensitive regional conflicts in the Asia Pacific with China’s involvement has recently drawn much international attention. This mostly refers to the aggravated situation in the South China Sea (SCS) where Beijing has expanded its military presence and continues pursuing land reclamation and military infrastructure construction on the occupied artificial features. In the context of an upgraded strategic cooperation between China and Russia, loud voices in Moscow demonstrate Russia’s support for Beijing’s political position on the questions of international law and arbitration, freedom of navigation, and internationalization of dispute settlement.

In his Russian media news conference on September 5 at the G20 summit in Hangzhou, Russian President Vladimir Putin openly supported the Chinese decision to ignore the Hague Arbitration Court ruling in the dispute between China and the Philippines, and stated that “interference by any power outside the region” would “hurt the resolution of these issues” and be “detrimental and counterproductive.”1 Moscow’s growing arms supplies to China in 2016–18, which include 24 Sukhoi Su-35 Flanker-E fighters and four battalions of S-400 anti-aircraft missile systems, among the others, are considered by many in the region as a significant step in the bilateral military cooperation between the two Eurasian giants with certain potential far-reaching implications for the security balance in the disputed maritime areas. Finally, the Russo–Chinese naval drills “Joint Sea 2016” held on September 11–19 in the SCS area have stirred speculation about Moscow changing its stance toward a more proactive direct military support of China in the turbulent waters.2 During his official visit to China in August 2016, the commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Scott Swift recalled that China and Russia had conducted six joint naval exercises over the last decade, and pointed to Sino–Russian naval drills in the South China Sea in September as an example of China’s “lack of transparency,” which could lead to “uncertainty” and have “a destabilizing effect in the region.”3 The Russian and Chinese leaders, on the contrary, believe that strengthening the two countries’ naval capability and interoperability would contribute to peace and stability. This divergence of views marks the emergence of a new strategic reality in the region and reflects Russia’s changing attitudes toward the matter.

Moscow’s Shifting Neutrality Rhetoric: The Devil Is in the Details

Both the Soviet government and the post-Soviet leadership of Russia have been pursuing a policy of non-interference in the territorial disputes in the South China. Sea. Konstantin Vnukov, the current Russian Ambassador to Vietnam, emphasized in an interview with me that Moscow had never deviated from its “neutrality position” in the China–Vietnam dispute even in the era of the Soviet–Vietnamese friendship and confrontation with China in the 1960–70s.4 Even the steadily growing strategic partnership with Beijing over the recent two decades has not made Moscow take sides in the disputes or acknowledge the legitimacy of China’s U-shaped “nine-dashed-line” and historical rights in the region. Nor has it convinced the Kremlin to scrap its political and economic cooperation with Hanoi or disrupt its arms supplies to China’s neighbors—claimants in the maritime disputes. Driven by predominantly pragmatic interests in the region, Moscow has been generally satisfied with the regional status quo admitting the role of the 2002 Declaration on the Conduct of the Parties in the South China Sea (DOC), standing against any meddling by nations other than the claimant countries in the South China Sea territorial dispute, and advocating for the freedom of navigation principle as a prerequisite for the solution of the disputes.5

However, the U.S. “pivot to Asia” and the subsequent effort to secure the freedom of navigation and military “capacity-building” among China’s opponents have increasingly turned the political low-intensity conflict into an element of a greater geopolitical game. Russian expert Evgeny Kanaev noticed that since the U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton raised the freedom of navigation issue at the 2010 Hanoi session of the ASEAN Regional Forum, the core of the problem shifted from sovereignty over the islands to the geopolitical rivalry between the U.S. and China.6

Prior to the breakup of Russia’s relations with the West over Ukraine in early 2014, Moscow’s interest in Asia lay predominantly in fostering economic cooperation with all actors who could reciprocate. Russia’s successful integration with the broader Pacific region required stability between the two major great powers, namely the U.S. and China, which would enable Moscow to balance and avert conflicts. To prevent the formation of a new bipolarity, Moscow tried to stay away from the contest for regional leadership, and instead promoted the concept of the major powers’ “collective leadership,” multilateral conflict management, and inclusive integration.

In its attempt to assume the role of a third party balancer, Moscow significantly improved its relationship with the Southeast Asian nations in 2008–2014 and actively supported the formation of an institutionalized security mechanism in the Asia-Pacific with the East Asia Summit (EAS) at the center, considered by the Kremlin as instrumental for maintaining stability, managing conflicts and promoting stronger “connectivity” in the Asia-Pacific. In that period, Russia’s stance on the issue of “internationalization” of the SCS disputes did imply some tacit support of collective arrangements or even outside facilitators within the existing multilateral institutions that would strengthen ASEAN’s consolidated position in its negotiations with Beijing with some elements of impartial international mediation and arbitration. For example, in May 2012 Russian ambassador in the Philippines Nikolay Kudashev publicly acknowledged that Russia was “not indifferent” to the situation which could have been addressed without any “meddling by nations other than the claimant countries in the South China Sea territorial dispute,” specifically referring to the United States. As a matter of balancing, however, Kudashev proposed that it was okay for “outsiders” like the United States, Russia and other European nations to provide assistance to claimant countries when asked. He went further saying that both Russia and the U.S. were “concerned about freedom of navigation in the sea,” which, as he believed, would be one of the aspects of a solution to the larger problem of the South China Sea.”7 One leading Russian expert on Asia at that time unambiguously pointed to the fact that, since China’s sovereignty claims expanded over the 80 percent of the SCS, Beijing’s declarations of its support of freedom of navigation in the area would mean that “from now on freedom of navigation would be secured by China, rather than formal legal norms shared by all.” This expert also warned the Kremlin that Russia should never recognize China’s nine-dashed line, remain consistent in its partnership with Vietnam, and even stimulate the formation of a political alliance between Vietnam and China.8 In the beginning of 2013 Russia’s ambassador to China Sergey Razov tried to dissolve the Kremlin’s ambiguity stating that “the lifting of bilateral disputes to collective, international, or regional level would not bring about appropriate solutions.”9 Moscow’s pragmatism and “balancing” behavior raised suspicions in the Chinese expert community: some observers accused the Russians of getting benefits from the U.S.–China rivalry and maximizing its gains in the era of geopolitical uncertainty.10

Since the outbreak of the Ukrainian crisis and Moscow’s split with the West, Moscow’s position toward the SCS disputes have increasingly become more articulated and sympathetic toward China. Firstly, Russia’s top governmental officials, while avoiding their open recognition of China’s historical rights in the South China Sea, formally supported China’s right to ignore the Hague arbitration July 12 verdict as illegitimate due to the one-sided claim by the Philippines and the court’s insufficient jurisdiction to judge on territorial disputes of sovereign states. Secondly, on the disputes’ “internationalization” issue, the Kremlin no longer attempts to stimulate a multilateral dialogue among the claimant states, trying to dissuade the U.S. from interfering and utilizing anti-China sentiments for militarization of the dispute. Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov stated in April 2016 that in the situation over the disputed isles in the South China Sea “all parties involved into the disputes should follow the principles of non-use of force and find political-diplomatic solutions acceptable for all the claimants of disputed territories.” While formally supporting neither side in the disputes, Russia obviously backs Beijing which opposes internationalization of the issue.11 The current Russian ambassador to China Andrey Denissov also echoed Lavrov’s words explaining that a new standoff in the SCS was incited artificially due to the interference of nonregional actors in conflict settlement.12 Thirdly, Moscow no longer believes that freedom of navigation may only be secured by the neutrality of all claimants and the adherence by all parties to international law. It is now China that is seen by the Russian government as the real guarantor of freedom of navigation. As ambassador Denissov stated, China “is more than anyone else interested in freedom of navigation in the area without any complicating circumstances.”13 It is noteworthy that this position corresponds to China’s self-declared role of a responsible great power which intends to apply legal procedures and negotiations in conflict settlement, avoiding forceful measures.14

These statements have been widely publicized by the official media in China showing Russia’s enhanced support of China’s position in the territorial disputes with its neighbors.15 Speculations about Moscow as a new ally of China in its multiple maritime disputes have gone so far that the Russian side had to officially dismiss all allegations of Moscow’s changing position toward this sensitive issue. Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Maria Zakharova had to remind the international community in July that Russia “had never been a participant of the South China Sea disputes” and “would not be involved into them.” Zakharova reiterated Moscow’s position of not taking sides and non-interference in the negotiations between the parties involved into the conflict, calling for a non-violent diplomatic solution of the issue.16

Zakharova’s comments came out in the midst of the heated debates in the West about the character and purpose of the China–Russia naval exercise in the South China Sea in September. Lack of information about the concrete area for joint maneuvers and Russia’s assurances fueled observers interest toward the “Joint Sea 2016” but did not cause much concern about China’s and Russia’s behavior. One key U.S. China analyst Bonnie Glaser was confident that the maneuvers would not necessarily become “a departure from what has so far been a pattern of relative restraint.17 While being novel operationally, the proceeding of the drills demonstrated the accuracy of this assessment.

The Joint Sea-2016: An “Entrapped” Russia?

Since the announcement of the Russian–Chinese naval exercises in the South China Sea earlier this year, some Russian observers confessed that this time the area of operations was coincidently chosen by Beijing and Moscow which set the order of the two parties’ joint maneuvers as early as in 2012. Having conducted similar exercises in 2012 and 2014 in which China’s Northern and Eastern Fleets were involved, 2016 marks the turn of the PLAN’s South Fleet that predetermined the parameters of joint operations. While the Russian naval commanders consider the Joint Sea-2016 as simply a positive cooperation experience,18 some experts in Moscow considered Moscow’s consent to hold the drills in the sensitive maritime zone of the South China Sea as “entrapment.” Military analyst Alexander Khramchihin maintains that Russia has become engaged into the conflict since it now formally supports China in its disputes with its Southeast Asia neighbors and, indirectly, Beijing’s conflict with the U.S. This expert warns the Russian government against the establishment of a permanent naval operational group with China, which, in his view, would substantially enhance China’s naval capability and further sharpen Moscow’s relations with Washington.19

Another Russian expert represents a more cautious view on the prospect of Russo–Chinese military cooperation. Alexey Maslov from the Russian Higher School of Economics points to the intensity and scope of Sino–U.S. military cooperation, which reduces the risks of open confrontation. Besides, as this expert asserts, Russia’s goal in this exercise is to demonstrate that Moscow has some military allies in the era of Western pressure. As for China, its joint maneuvers with Russia is the demonstration of international support of China’s maritime claims in the disputed waters.20 Western analysts also stress that being one of the major suppliers of arms to China’s opponents in the dispute, Moscow remains careful to maintain its balancing act on the South China Sea maritime disputes between Beijing and Hanoi, which could be one reason why Russia’s Joint Sea-2016 detachment was relatively small and did not include any of the Russian Navy’s newest warships. Franz-Stefan Gady considers the “Joint Sea-2016” a kind of symbolic gesture, he believes that the major rationale behind the joint drills is “political rather than practical and is meant to emphasize the burgeoning security partnership between the two countries.”21 Japanese observer Yu Koizumi believes that, while stressing its close ties with China, Russia tries to keep distance from territorial problems, and the Kremlin’s rhetoric by no means expresses Russia’s full support of China in the South China Sea issue.22

These views conceal the real significance of the maneuvers for both Russo–Chinese strategic cooperation and the changing security environment in the Asia-Pacific region.

First of all, the 2016 naval drills in the South China Sea appeared to be the most sophisticated and multidimensional since the partners started joint naval exercises in 2012. The “Joint Sea-2016” may be considered as a sign of the growing intimacy of the two countries’ military forces.

Compared with the “largest ever” joint Sino–Russian naval maneuvers held in August 2015 in the Sea of Japan, the Joint Sea-2016 involved a total of 18 warships, among which Russia dispatched three warships (the big anti-submarine ships Admiral Tributs and Admiral Vinogradov, the big amphibious ship Peresvet) and two supply vessels (the sea towboat Alatau, and the tanker Pechenga). China was represented by guided-missile destroyers, frigates, landing ships, supply ships and two submarines. Air operations were supported by 21 aircrafts and eight helicopters. A total of 160 Chinese and 96 Russian marines participated in the maneuvers.23 The three stages of the drills included 30 naval live fire drills, anti-submarine warfare and air defense maneuvers, and also the island-seizure exercises.

At first glance, both Russia and China conducted their drills in a less contentious site, refraining from holding their exercise in the southern part of the South China Sea, close to the Spratly islands, which would raise unprecedented controversy and increase tensions in the area. Territorially, the “Joint Sea-2016” took place near the city of Zhanjiang, located in southern Guangzhou province and north of the South China Sea’s Hainan Island, where China’s main regional military base is located.24

However, even with the limited size of the joint fleet, the Chinese and Russian navies have gone beyond the standard feature of the two countries’ maneuvers which combined search and rescue operations, amphibious missions and airborne landings, undertaking an “island-seizing” exercise, with an upgraded level of interoperability and the improved the quality of exercises. Abhijit Singh believes that the trajectory of recent maritime interactions suggests that the partnership is beginning to outgrow the original template of military cooperation.25 Chinese Navy spokesperson Liang Yang explained that this time the drills were realistic, with the unprecedented involvement of information technologies, standardization, and the unified and more practical command and control procedures.26 Much attention was devoted to landing operations (on Dashu island) and the more sophisticated anti-submarine operations, engaging early warning helicopters (Ka-27PL and Z-9C), JH-7A aircraft, Chinese destroyer Guangzhou, guided-missile frigates Huangshan, Sanya and Daqing, and the Russian technologically advanced anti-submarine destroyer Admiral Tributs.27 More importantly, the two navies successfully conducted joint combat and maneuvering operations within the joint tactical naval and anti-missile group, as well as joint targeting and joint target coordination.28

Another significant aspect of the “Joint Sea-2016” maneuvers is related with Russo–Chinese changing strategic worldview, which is utterly confrontational to current U.S. global behavior. The documents signed during Russian President Putin’s visit to Beijing on June 25, 2016 demonstrate China’s support of Moscow’s policy of balancing against the U.S. as a positive measure to deter expansionism and aggression.29 The Kremlin increasingly looks into its activities in the South China Sea as part of a worldwide “struggle for peace” by means of power balancing with the hegemonic U.S. The Russian leaders regard Moscow–Beijing relations as an instrument of strategic stability, aimed at curtailing U.S. unilateral actions and uncontrolled uses of force. Both Russian and Chinese leaderships believe that their effort to preserve state sovereignty would eventually solve the problem of global instability. Russia’s and China’s strategic capacity to deter the U.S. by military means becomes the major guarantee of global peace and stability. Hence, both Russia and China are determined to protect their respective zones of strategic interests. As Aaron Austin contends, China is clearly intent on developing the largest military and maritime law enforcement force in the Asia-Pacific region.30

So, it is not primarily access to natural resources or commercial transportation routes in the disputed waters of the South China Sea that determine China’s strategy. Looking at the vulnerable condition of the southern elements of its nuclear defense system, Beijing increasingly enhances its own military control capability in the area. China is actively considering a South China Sea Air Defense Interception Zone (ADIZ) and is a continuing to block Philippine access to the waters near Scarborough Shoals. There are also reports that China is considering the deployment of floating nuclear power plants to the South China Sea to provide power to offshore platforms.31 Beijing regards these waters as a corridor for its growing nuclear submarine fleet harbored in the Yulin naval base on the Hainan island. The development of the military infrastructure on the disputed rocks in the Paracels and Spratly area is considered in China as part of its ambitious plan to set up a series of protected outposts along the ways of China’s nuclear submarines patrolling in the Western Pacific.32 In this context, China’s claims in the South China Sea may be compared to the strategic role of the Crimea for securing Russia’s military control over the Black Sea and the protection of Russia’s vital strategic nuclear defense infrastructure. As Abhijit Singh suggests, the nautical synergy also reveals an enduring correlation between geopolitics and maritime strategy. The Sino–Russian maritime relationship seems driven by political motivations and a desire to jointly counter U.S. military pressure.33 Some leading military experts in Russia also regard China’s military assertiveness in the Pacific as beneficial for Russia’s own national security.34 There are also proposals in the Russian expert community to form a permanent Russo–Chinese joint naval operational group enhanced by Russia’s Tu-22M3 strategic bombers to deter the U.S.–Japanese naval coalition forces in the region.35 Dmitry Novikov from Russia’s Higher School of Economics, believes that by supporting China Russia will contribute to the balance of power in the Asia- Pacific to eventually stabilize the region.36

Conclusion

The recent Russo–Chinese naval exercise “The Joint Sea-2016” held in the South China Sea marks a significant shift in Russia’s strategic role in the changing Asia-Pacific security environment. Beyond the multiple statements on the official level reiterating Russia’s “neutrality” and non-involvement in the territorial disputes, Moscow’s more articulated and nuanced position toward internationalization of dispute settlement and the freedom of navigation problem demonstrate that Russia’s participation in China’s activities in the disputed areas add more than just a symbolic support to Beijing’s policies. Russia’s changed rhetoric and practical actions, along with the increased sales of advanced weapons to China, should be regarded as a manifestation of the strategic congruency of Chinese and Russian visions of the evolving global order which increasingly depends on the reanimated geopolitical factors. The relationship with the U.S. is regarded by the Chinese and Russian leaders as systemic confrontation, which pushes the two Eurasian giants into the policy of hard and soft balancing. Beijing has learned the Crimea lesson: the real battle for sovereignty requires direct military control and constantly upgrading China’s defense capability. Being alienated from the West, Russia serves as an ideal ally in the uphill battle for regional and global leadership.

Notes

1 “Vladimir Putin Answered Russian Journalists’ Questions Following His Working Visit to China to Take Part in the G20,” September 5, 2016 external pagehttp://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/52834call_made

2 Chris Buckley, “Russia to Join China in Naval Exercise in Disputed South China Sea,” The New York Times, July 29, 2016, external pagehttp://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/29/world/asia/russia-chinasouth-china-sea-naval-exercise.html?_r=1call_made

3 Franz-Stefan Gady, “Top US Naval Officer in Asia Calls for Military Transparency in China Visit,” The Diplomat Online, August 11, 2016 external pagehttp://thediplomat.com/2016/08/top-us-naval-officerin-asia-calls-for-military-transparency-in-china-visit/call_made

4 Ambassador Vnukov’s conversation with the author, May 26, 2015.

5 Roy C. Mabasa, “Russia Against Meddling,” The Manila Bulletin, May 20, 2012, external pagehttp://www.mb.com.ph/articles/360014/russia-against-meddling#.UIRTUcXR6fgcall_made

6 Evgeny Kanaev, “The South China Sea Issue: A View From Russia,” in Victor Sumsky, Mark Hong, Amy Lugg (eds.) ASEANRussia: Foundations and Future Prospects. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS), Singapore, 2012, p. 98.

7 Nikolay Kudashev’s remarks may be found here: “Russia Denounces Meddling from ‘Outsiders’ in South China Sea,” May 22, 2012 external pagehttp://bbs.english.sina.com/viewthread. php?tid=82826call_made

8 Dmitry Mosyakov, “Falling Short from Foul Play: China’s Policy in the South China Sea,” (Дмитрий Мосяков, На грани фола: политика Китая в Южно-Китайском Море), Security Index (Индекс Безопасности), Moscow, Vol. 19, No. 4(107), (Winter 2013), pp. 58; 67 external pagehttp://www.pircenter.org/articles/1593-na-grani-fola-politika-kitaya-v-yuzhnokitajskom-morecall_made

9 Russian Ambassador to China Sergey Razov’s Interview to the “Russian Newspaper” (Interview Интервью Чрезвычайного и Полномочного Посла России в КНР С.С.Разова, опубликованное в «Российской газете»), February 1, 2013 external pagehttp://www.mid.ru/web/guest/maps/cn/-/asset_publisher/WhKWb5DVBqKA/content/id/124698call_made

10 Kang Lin, “Russia Benefits from the South China Sea Disputes,” (康霖:俄罗斯是南海争端的获益者), Global Times (环球时 报), August 6, 2012, external pagehttp://opinion.huanqiu.com/1152/2012-08/2990668.htmlcall_made

11 Interview of Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov to the Mongolian, Japanese and Chinese Media Prior to His Visit to These Countries” (Интервью Министра иностранных дел России С.В.Лаврова СМИ Монголии, Японии и КНР в преддверии визитов в эти страны), Moscow, April 12, 2016 external pagehttp://www.mid.ru/press_service/minister_speeches/-/asset_publisher/7OvQR5KJWVmR/content/id/2227965call_made

12 An Interview of the Russian Ambassador to China A.I. Denisov to Russian News Agencies ‘Russia Today’ and TASS (Интервью Посла России в КНР А.И.Денисова информагентствам «Россия сегодня» и ТАСС), June 21, 2016 external pagehttp://www.mid.ru/ru/maps/cn/-/asset_publisher/WhKWb5DVBqKA/content/id/2327002call_made

13 An Interview of the Russian Ambassador to China A.I. Denisov to Russian News Agencies ‘Russia Today’ and TASS (Интервью Посла России в КНР А.И.Денисова информагентствам «Россия сегодня» и ТАСС), June 21, 2016 external pagehttp://www.mid.ru/ru/maps/cn/-/asset_publisher/WhKWb5DVBqKA/content/id/2327002call_made

14 Chinese Defense Ministry: The Day the US Fleet Stops Provoking would Be the Moment of Stability and Peace in the South China Sea, (中国国防部:美军舰机停止挑衅之日就是南海稳定和平之时), July 8, 2016, China Radio International (CRI) Online, external pagehttp://mil.cri.cn/20160708/be80fa29-e806-9b66-e9a9-c75e9eac6cc1.htmlcall_made

15 “From Beijing with Love: Sergey Lavrov is assured that relations with China have never been so good” (Из Пекина с любовью. Сергей Лавров убедился, что отношения с КНР хороши, как никогда). Lenta.ru April 30, 3016, external pagehttps://lenta.ru/articles/2016/04/30/beijingcalling/call_made

16 Russia Refuses to Be Involved into the South China Sea Disputes (Россия отказалась втягиваться в спор за Южно-Китайское море), Lenta.ru July 14, 2016 external pagehttps://lenta.ru/news/2016/07/14/without_us_please/call_made

17 Chris Buckley. Op. Cit.

18 The Russian Navy’s deputy commander Vice-Admiral Alexander Fedotenkov appraised annual change of combat conditions as being positive for “gaining experience.” “Joint Sea-2016: the Chronology and Major Stages of the Joint Russian–Chinese Exercises,” Russian Defense Ministry, September 20, 2016 external pagehttps://defence.ru/military-exercise/morskoe-vzaimodeistvie-2016-khronika-sobitii-i-epizodov-rossiisko-kitaiskikh-uchenii/call_made

19 Anton Mardasov, “In the Wake of a Crafty Dragon,” (В кильватере коварного дракона), Svobodnaya Pressa Online, July 29,2016, external pagehttp://svpressa.ru/war21/article/153424/call_made

20 Ibid.

21 Franz-Stefan Gady, “Are China and Russia Holding Joint Military Drills in the South China Sea?” The Diplomat Online, July 7, 2016 external pagehttp://thediplomat.com/2016/07/are-china-and-russiaholding-joint-military-drills-in-the-south-china-sea/call_made

22 Yu Koizumi, “Why were the Sino–Russian Maneuvers held in the South China Sea Area?” (小泉悠, 中露合同演習はなぜ 南シナ海で行われたのか) Wedge Report, September 27, 2016 external pagehttp://wedge.ismedia.jp/articles/-/7837call_made

23 “Joint Sea-2016: the Chronology and Major Stages of the Joint Russian-Chinese Exercises.” Op. Cit.

24 Bill Gertz, “Counter-Pivot: China, Russia Hold Massive South China Sea War Games,” Asia Times Online, September 20, 2016 external pagehttp://atimes.com/2016/09/counter-pivot-china-russiahold-large-scale-s-china-sea-war-games/call_made

25 Abhijit Singh, “Why Russia and China’s Combat Drills in the South China Sea Matter,” The National Interest, September 16, 2016 external pagehttp://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/why-russia-chinascombat-drills-the-south-china-sea-matter-17729?page=showcall_made

26 “China and Russia Have Started the Largest Joint Naval Drills in History,” (Китай и Россия начали самые масштабные в истории совместные военно-морские учения), Geopolitika. info September 13, 2016 external pagehttp://geo-politica.info/kitay-i-rossiya-nachali-samye-masshtabnye-v-istorii-sovmestnye-voennomorskie-ucheniya.htmlcall_made

27 Bill Gertz. Op. Cit

28 “Joint Sea-2016: the Chronology and Major Stages of the Joint Russian–Chinese Exercises.” Op. Cit.

29 “China, Russia Sign Joint Statement on Strengthening Global Strategic Stability,” Xinhuanet.com, June 26, 2016 external pagehttp://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-06/26/c_135466187.htmcall_made

30 Aaron Austin, “China’s Subtle Strategy in the South China Sea,” The United States Institute of Peace Brief, No. 154, July 24, 2013 external pagehttp://www.usip.org/publications/china-s-subtle-strategy-in-the-south-china-seacall_made

31 Mark E. Rosen, “China Has Much to Gain from the South China Sea Ruling,” The Diplomat, July 18, 2016, external pagehttp://thediplomat.com/2016/07/china-has-much-to-gain-from-the-south-china-sea-ruling/call_made

32 “Hot Summer of 2016: Is War in the South China Sea Possible and What Is the PLA is Getting Ready For,” (Жаркое лето 2016-го: возможна ли война в Южно-Китайском море и к чему готовится китайская армия), South China Insight, Hong Kong, July 25, 2016 external pagehttps://www.south-insight.com/node/218369call_made

33 Abhijit Singh. Op. Cit.

34 Viktor Litovkin holds that “the construction of Chinese military infrastructure will provide Russia with protection in the area against U.S. Navy ships and the Aegis system and SM-3 and Tomahawk missiles.” Victor Litovkin, “Russia Could Gain from Backing China in South China Sea Disputes,” Russia Beyond the Headlines, September 8, 2016 external pagehttp://rbth.com/international/2016/09/08/russia-could-gain-from-backing-china-in-south-china-sea-disputes-experts_628057call_made

35 Russian military analyst Konstantin Sivkov represents this position. See: Anton Mardasov. Op. Cit.

36 Scalene Triangle. The goals and capabilities of Russia in its relations with the Chinese–American Duo Неравнобедренный треугольник. (Цели и возможности России в отношении китайско-американского дуэта). Russia in Global Affairs, Russian edition. June 7, 2015, external pagehttp://www.globalaffairs.ru/number/Neravnobedrennyi-treugolnik-17499call_made

About the Authors

Claire Christian is the acting executive director of the Antarctic and Southern Ocean Coalition.

Vitaly Kozyrev is a professor in the Department of International Studies at Endicott College in Boston.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.