The ´Genocide´ Taboo: Why We´re Afraid of the G-Word

16 Jan 2017

By Alice C Hu for Harvard International Review (HIR)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageHarvard International Reviewcall_made on 11 January 2017.

On July 11, 2015, Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić joined tens of thousands of people in the town of Srebrenica to pay respect to the victims of a massacre that occurred exactly 20 years ago. In the final stage of the Bosnian War, more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys were executed by Bosnian Serb soldiers who took over Srebrenica, a UN-designated “safe haven.” Vučić’s presence was intended to signal progress toward reconciliation between Bosnian Muslims and Serbs, but for many families and visitors who gathered at the town, true reconciliation cannot be achieved without use of a word — genocide. The large crowd in Srebrenica chanted “genocide” at the prime minister, whose government still refrains from calling the event a genocide even as it “unambiguously condemns” what happened.

Srebrenica is not alone. In addressing ethnic conflicts, past and current, the usage of the “G-word” has taken on an exceptional importance for both victims and the accused.

In Guatemala, the indigenous Maya Ixil, who endured ethnic cleansing under General Efraín Ríos Montt, spent 13 years building the case of genocide against him. It finally resulted in the first indictment of its kind in 2013. In Turkey, before the one hundredth anniversary of the Armenian genocide in April 2015, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan plainly stated that any motion by the European Parliament to recognize the Armenian genocide would “go in one ear and out the other.” In the United States, Secretary of State Colin Powell made history in 2004 when he broke the de facto “genocide” ban in his description of the conflict in Darfur, becoming the first member of any US administration to formally apply the word to an ongoing conflict.

How did this eight-letter word become so important? In confronting complex conflicts that involve millions of lives, how did the most urgent question become “should this be called a genocide?” Besides being one of the most powerful words in international law, “genocide” has also accrued a worldwide cultural and political significance that few other words have. Yet, the origins and implications of the “G-word” itself are seldom analyzed — and they deserve more attention if we are to better understand the ongoing disputes around genocide.

“Genocide” and Intent

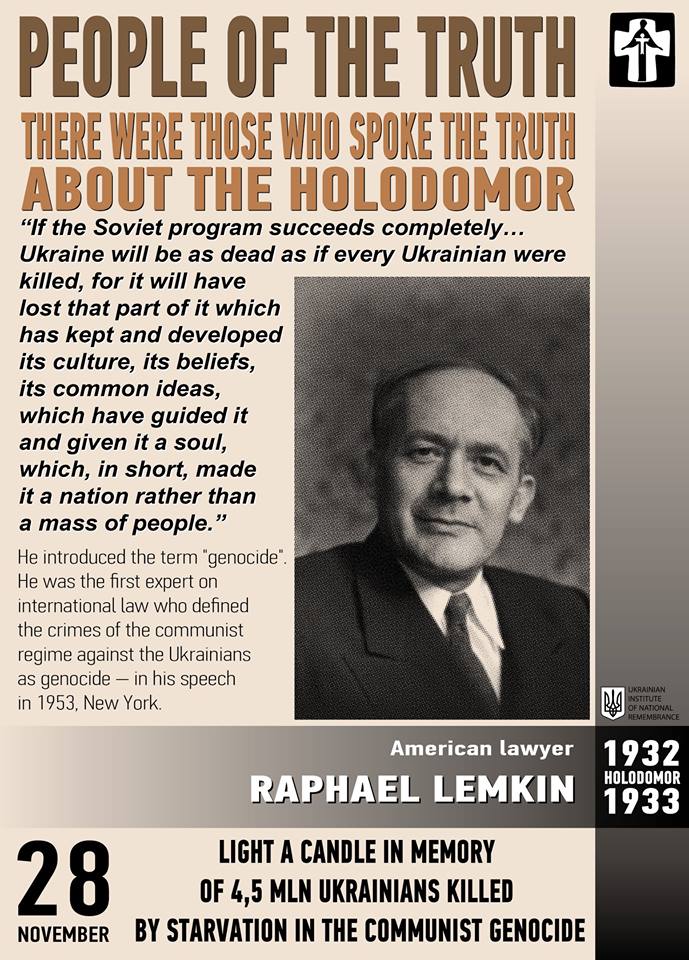

The word “genocide” is a hybrid of the Greek prefix genos, meaning race, and the Latin suffix cide, meaning killing. It was coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1944. A Polish lawyer and a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, Lemkin was the first to study what was occurring in his home state from a legal standpoint. Genocide, in his view, is “a premeditated crime with clearly defined goals, rather than just an aberration.” According to Lemkin, unlike other cases of mass violence, genocide has targeted intentions. Lemkin went on to serve as the Chief Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials. Four years later, largely due to the efforts of Lemkin and his supporters, the term “genocide” was enshrined in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, and was adopted by the UN General Assembly on December 9, 1948.

Lemkin’s influence on our contemporary definition of genocide cannot be understated. In accordance with his view, Article II of the Convention defines genocide as specific “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.”

From a technical standpoint, this definition should expand the protection of international law. While genocidal acts include killing members of a group, they also include inflicting mental harm, imposing measures intended to prevent births, and forcibly transferring the children of the targeted group.

Furthermore, unlike crimes against humanity, no person needs to be harmed for the event to be called genocide. According to Article II (c), “inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about physical harm” with intent to destroy the group is sufficient. It is not necessary for the calculated conditions to succeed in bringing harm. Rather, the intent is the key to determining whether or not an event is genocide.

The Darfur Case

The “intent” in genocide’s definition, however, seems to have worked more like a lock than a key — excluding victims of wide-scale ethnic violence from legal protection.Take Darfur, an ongoing conflict that has led to the deaths of an estimated 400,000 people over 13 years. More than 2.5 million people out of the region’s 6 million-person population have also been displaced.

The roots of the issue are complex. A region in western Sudan, Darfur has been deep in conflict since the non-Arab tribes, citing systematic discrimination, took up arms against the Arab-led government in 2003. Since then, the government- backed Arab paramilitary, the Janjaweed, has been raiding villages in Darfur and massacring their residents, most of whom are black Africans belonging to the Fur, Zaghawa, and Masalit groups.

The number of deaths, refugees, destroyed homes, and razed villages are so high that it is disorienting. Yet, Darfur did not receive the assistance legally guaranteed to cases of genocide because it lacked intent as defined by the Convention, according to many politicians and scholars.

In face of widespread resistance to labeling the Darfur case a genocide, Powell’s decision to use the “G-word” in 2004 before the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee became monumental. Influenced by the infamous 1994 Rwandan Genocide, Powell’s Assistant Secretary of State Lorne Craner undertook an investigation on Chad’s borders, where many of Darfur’s refugees were fleeing. The results showed evidence of massive killings, rape, serious bodily harm, and destruction of necessities for life, all of which was in line with the language of Article II. The victims were also of mostly the same ethnic groups, but some still questioned whether the intent was proven.

Powell, facing a decision that has troubled so many political leaders, justified calling it a genocide. Nine days after his monumental decision, the UN Security Council adopted a resolution to conduct an investigation in Darfur, and in 2010, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an indictment for genocide against Omar al-Bashir, the president of Sudan.

While Powell’s decision is commendable to many, it also shows the subjective and even arbitrary nature of the genocide label. The clear and conclusive language of Article II breaks down into messy human variables when applied to real cases. This variability, in turn, spurs disagreements and questions of legitimacy when using the term “genocide.”

Burden of Responsibility

The trouble with the “G-word,” however, is more than a semantic quarrel. It would be misleading to discuss the incredible precaution with which countries approach the genocide question without first taking into account Article I of the Convention. The Article states, in brief but powerful terms: “The Contracting Parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.”

This obligation worried the United States, which had finally ratified the Convention in 1988, after four decades of congressional protest over the infringement of national sovereignty. Although Article I does not specify what type of actions the obligation entailed, the US government nevertheless avoided using the word “genocide” for decades. A declassified briefing by the National Security Archives revealed that, during the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, State Department lawyers were concerned that calling the event genocide might require the Clinton administration to “actually ‘do something.”

Aside from Powell’s 2004 hearing, the ban on the “G-word” seems to have remained unbroken. In his 2008 bid for president, Barack Obama promised to recognize the Armenian genocide if elected. However, on the one hundredth anniversary of the event in 2015, Obama evaded the word.

Unsurprisingly, the usage of “genocide” carries weighty legal and political consequences in relations between the United States, Turkey, and Armenia. The Armenian genocide remains the single biggest source of tension between Armenia and Turkey. For many Armenian- American groups, silence on the word “genocide” represented a “surrender to Turkey,” as stated by Ken Hachikian, chairman of the Armenian National Committee of America. But in a time of growing conflicts in the Middle East, the US government is cautious about offending Turkey, a crucial partner in the region. More than ever, besides existing in a labyrinth of legality, “genocide” functions as an instrument in geopolitical chess.

Rethinking “the Stain Called Genocide”

On a fundamental level, genocide has become perhaps the worst public indictment, not for its illegality or political consequences, but for the moral and cultural shame it brings. Indeed, in the struggles over whether particular conflicts should be called genocide, the concern on both sides is largely emotional.

For indigenous Mayan victims under Ríos Montt’s dictatorship, the importance of his trial was unrelated to any geopolitical significance. It was about having their reality, their truth, recognized. “Each one of us who is watching has lost their mother or their grandparents. That is why we are here,” said one victim at the trial. “God knows that we are telling the truth.”

For some of them, it didn’t matter that 10 days after Ríos Montt was found guilty of genocide, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court annulled the verdict on technical grounds. It didn’t matter that, in the end, the former dictator was able to evade imprisonment on account of his mental conditions. For the Mayan community, “la sentencia está vigente — the verdict is valid.” Once the label of genocide is stamped, nothing can erase it.

Perhaps that is why, rather than citing legal implications, Turkish President Erdoğan stated, “It is out of the question for there to be a stain or a shadow called genocide on Turkey.” For Erdogan and many others, the greatest consequence of the “G-word” is not legal ramifications or financial compensation, but rather a legacy of shame that, once accepted, cannot be shed. When Raphael Lemkin coined “genocide,” he helped give the term not only its legal dimension, but also its moral character. Lemkin was motivated by the Holocaust — its blatant cruelty and lack of humanity laid the psychological framework in thinking about genocide. As such, many people simply cannot imagine that their grandparents, their spouses, or their loved ones could partake in a crime as heinous as the Holocaust.

The problem with this framework is that it assumes that ordinary people cannot commit these crimes, but that is exactly what occurred during the Rwandan Genocide. There was no evil gene, but there was a colonial racial caste, a lifetime of ethnic propaganda, and a history of hate. Ordinary people also committed genocide in Srebrenica, in Guatemala, in what is now eastern Turkey, and in Darfur.Each of these cases has its own history, but to insist that the act of genocide is impossible for ordinary people only hinders us from preventing future tragedies.

The establishment of genocide in international law and the global psyche has been both a blessing and a curse. While it invites near universal condemnation of crimes recognized as genocide, it also makes this recognition extremely difficult to establish. The standards for recognition, centered on proof of intent of extermination, are ambiguous and can be used by perpetrators to their advantage. The legal responsibility of the Convention also makes ratifying countries less likely to use the “G-word.” These problems are unlikely to be addressed through formal changes: the UN is unlikely to amend the language of the Genocide Convention any time soon, and governments are unlikely to change their “G-word” stances either.

But what can be changed, and perhaps is more important in the end, is our attitude toward genocide. Though characterized by the lack of humanity, genocide is still about humans — ordinary people — who act to destroy another group based on their identity. To end the resistance to the “G-word,” we must stop conceptualizing genocide as a crime alien to us. We must realize that it doesn’t take an evil predisposition or faulty culture to spark genocide. Only then can we use the “G-word” without it being seen as a condemnation of an entire people. And only then can we not only call it for what it is, but also move to prevent it.

About the Author

Alice C. Hu joined the HIR as a staff writer in 2014, and covers topics including US foreign policy, international law, and human rights. She served as Writing Chair for the 2015-2016 term. Twitter: @alicehu_.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.