Foreign Direct Investment into Russia since the Annexation of Crimea

24 Jul 2017

By David Szakonyi for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 12 July 2017.

Over the last decade, foreign investors have been riding the roller coaster of doing business in Russia. For years, Russia has been viewed as a leading emerging market, boasting a huge consumer base, a highly educated workforce, and ample natural resources. But investor confidence in Russia plummeted in 2014 in the wake of a precipitous drop in oil prices and the imposition of international sanctions. Suddenly Russia was isolated both politically and economically from the West, and the volume of foreign direct investment (FDI) shrank.

Anecdotal evidence suggests the tide may be turning. Leading multinationals have announced expansion plans, while Russian officials have successfully courted large-scale investments from China, Qatar, and India. Which companies are braving significant political risk to invest in Russia under the sanctions regime? How successful overall has Russia been at reducing its reliance on Western financial investors?

Statistical evidence confirms foreign investors are dipping their toes back into Russian waters. This cautious optimism began before the most recent US presidential elections and extends into sectors beyond oil and natural gas production. Specific policies adopted by the Russian government are partly responsible. Incentives passed to localize production and the development of a multilateral investment fund have helped compensate for the drop from other investors spooked by political risk. FDI will continue to trickle into Russia as long as the economy remains relatively stable. But fundamental obstacles prevent a complete rebound in foreign investment. Tackling rampant corruption, further diversifying the economy, and reducing political tension with the West will unleash strong pent-up demand among multinationals to re-engage with Russia.

Withered Investment under Political Uncertainty

After a slow recovery from the 2008 financial crisis, foreign investors were already beginning to pile back into Russia by early 2013. Russia had finally joined the WTO the year before, and talks were underway to liberalize some of the restrictions on FDI into strategic sectors. Moreover, upon taking office for his third term, President Putin had set a target of dramatically improving Russia’s ranking on the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business scale. Shortly thereafter, policymakers simplified procedures for starting businesses, eased property registration rules, and introduced electronic services for businesses to pay taxes and submit customs documents. In 2013, a United Nations report ranked Russia as the number three most attractive country worldwide for foreign investment (after the US and China).

But the overall investment atmosphere would soon darken. By the end of 2013, clear signs of stagnation were on hand, as fixed-capital investment slowed to a trickle and GDP growth barely registered. Analysts were concerned that the boom years of the mid-2000s had given way to an altogether more fragile and resource-dependent economy. The collapse in the price of a barrel of oil in 2014 proved them right. Russia’s economy sped downward, with the ruble rapidly depreciating and Russian policymakers scrambling to prevent a repeat of the 1998 financial crisis. Foreign investors fled seemingly overnight, as overall FDI into Russia dropped by roughly 50% in 2014 in comparison to the boom year of 2013.

International sanctions compounded the damage from the drop in oil prices. Beginning in March 2014, the US and the EU imposed several types of measures to try and compel Kremlin decision-makers to renounce the annexation of Crimea and enforce a settlement for the conflict in Ukraine. Foreign asset freezes and travel bans were imposed on individuals regarded as responsible for Russia’s policy towards Ukraine. Western governments severely restricted commercial opportunities available to politically connected Russian companies. These sectoral sanctions prevented key firms operating in the financial, energy, and defense sectors from taking on new long-term debt, as well as importing dualuse technology. Partnerships between oil companies were among the first to be put on hold. Western multinationals quickly withdrew from providing technology and services to Rosneft and Gazprom Neft, who were forced to hunt for substitutes, domestic or otherwise, to continue exploiting their reserves.1

The sanctions also caused a regulatory nightmare. From 2014–2016, Russian companies were regularly being added to the sanctions list and the language of the rules tightened, actions that could jeopardize preexisting loans and investments and reduced the appeal of entering into new ones. Although more and more parties included “sanctions clauses” in their business contracts, multinationals that didn’t know the ultimate beneficiaries of their Russian business partners, a difficult task for due diligence, were especially at risk. Sanctions increased the costs for a variety of multinationals operating in Russia, especially financial services firms, who were forced to devote more resources to ensuring compliance.

Russia’s own retaliatory measures further complicated the situation for investors. In August 2014, the Russian government imposed its own countersanctions, banning dairy, meat, and produce imports from the EU, the US, Canada, Australia and Norway. Longstanding trading relationships within the agricultural sector collapsed. In the midst of all of this tension, a row with Turkey over a downed fighter jet temporarily exacerbated economic relations with another important economic partner. By the end of 2015, FDI into Russia had plunged another 92% year-on-year, totaling just under $10 billion.

Turning the Tide

However, things would not stay at rock bottom for long. Russia’s Central Bank has appeared to have turned the corner on runaway inflation, and moved to taking over bad banks and cleaning up the financial sector. By the end of 2016, industrial production had exceeded expectations, and state officials are predicting small but positive GDP growth for 2017, a surprise to many analysts who had feared much worse.

Foreign investment has not been far behind. Official data from the Russian State Statistics agency confirms this renewed interest among multinationals in Russia. While total net FDI inflows were just $6.5 billion in 2015, just through the first three quarters of 2016, that number had increased to $11.1 billion. FDI stock in Russia surpassed $320 billion through the third quarter of 2016. A good portion of that upswing is due to “round-trip” investment from offshore sites such as Cyprus, Bermuda, and the British Virgin Islands, but companies solely based in major world economies also have jumped back in.

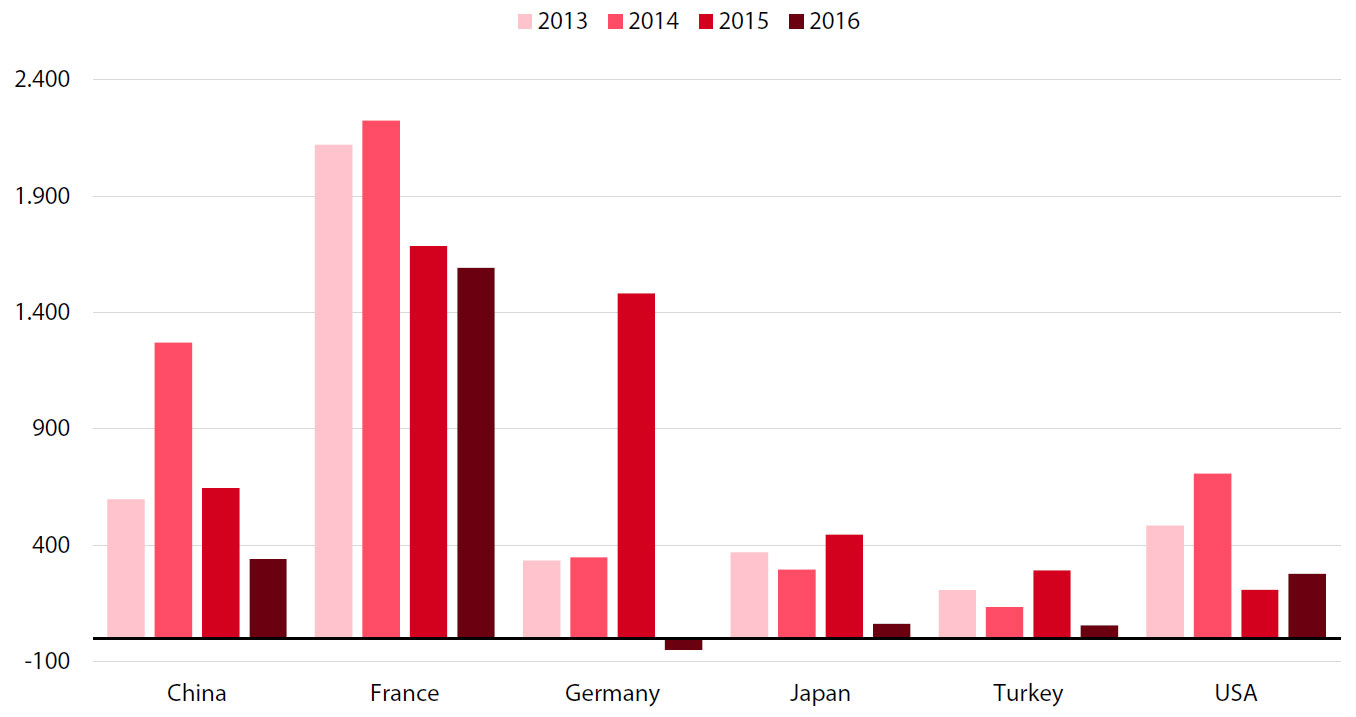

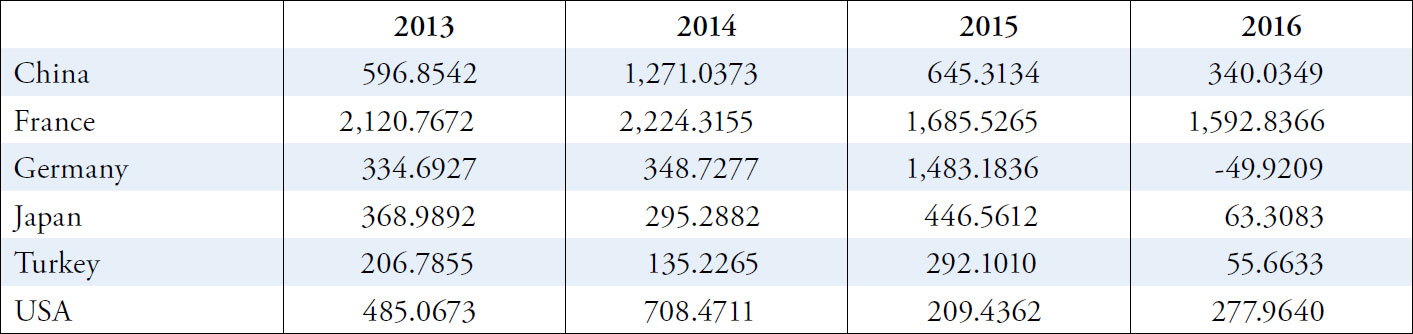

Figure 1 and Table 1 respectively plot foreign direct investment in-flows over the past four years for Russia’s six main partners (which are not offshore financial centers). Note that final data on 2016 is not yet available so statistics for that year reflect the total for the first three quarters. The overall picture is complex. German companies pushed ahead in 2015 despite the uncertain economic climate, but appeared to take their foot off the gas in 2016, ceding ground to U.S. companies. Both French and Chinese have maintained strong growth in their investment positions since the sanctions were introduced, though in the latter case, perhaps not at the levels many Russian officials had hoped for. China appears reluctant to jump headfirst into the Russian market, preferring instead to snap up key infrastructure and energy-related assets that help to extend its influence across Eurasia. Much more work remains for Russia to completely pivot to the East.

Figure 1: Foreign Direct Investment Inflows, Russia’s Six Main Partners (mln. USD, 2013–2016*)

Table 1: Foreign Direct Investment Inflows, Russia’s Six Main Partners (mln. USD, 2013–2016*)

Where specifically has investment continued to flow? First, long-term efforts to privilege locally produced goods have affected strategic decision-making by foreign firm managers. Culminating in the countersanctions on agricultural products, the Russian government for several years has embarked on an ambitious experiment to institute import substitution. Various incentives have been introduced both to spur domestic production of key goods and services, as well as to entice foreign firms to set up production facilities on Russian territory. In response, several multinationals have opted to localize their production facilities to avoid significant disadvantages in reaching consumers. Companies that have dragged their feet in complying with some new localization policies, such as LinkedIn, have even faced outright bans on operating in Russia.

The pharmaceuticals industry has been one of the few bright spots for investment under sanctions. Since the 2008 financial crisis, domestic drug producers have enjoyed substantial preferences under Russian state procurement, through which the bulk of medicines purchased are done.2 In late 2014, US-based Abbott Laboratories purchased Veropharm, a leading Russian manufacturer of generic drugs, for $306 million; the acquisition also included a newly completed factory. Indian giant Sun Pharma acquired an 85% share of Biosintez which operates a highly capable manufacturing facility in Penza.3

Progress attracting new localization by multinationals in the food industry has been somewhat slower. Large investments have been promised by Vietnamese and Thai companies into milk and dairy facilities, two key products falling under the counter-sanctions. Such new concerns hope to take advantage of the renewed emphasis on Russian food exports. Similarly, government officials are courting Italian dairy manufacturers hurt by the embargo, but still eager to compete with the vastly inferior domestic cheese substitutes popping up on the market. But given the rush of Russian-led investment into agricultural land, competition will be especially fierce. Concurrent with the food embargo in August 2014, Russia took steps to prevent foreigners from investing in agricultural land, either through their own subsidiaries or majority stakes in domestic companies.

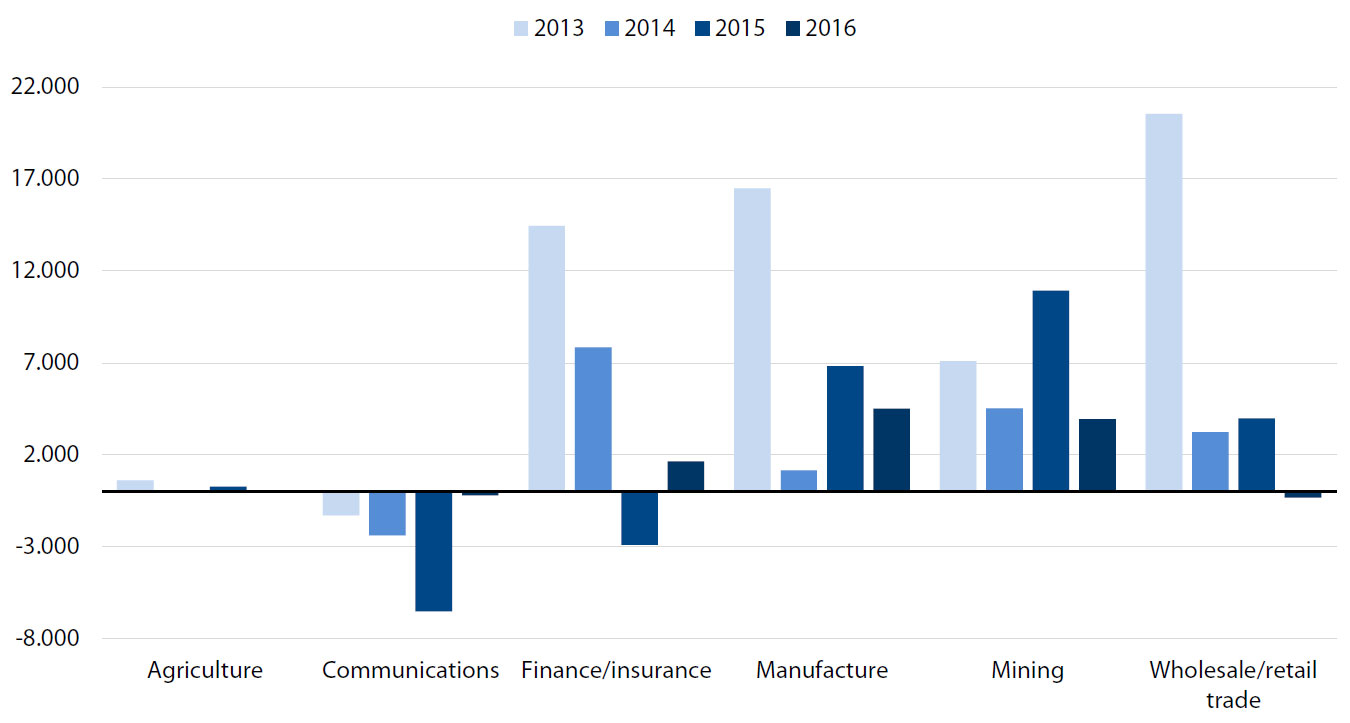

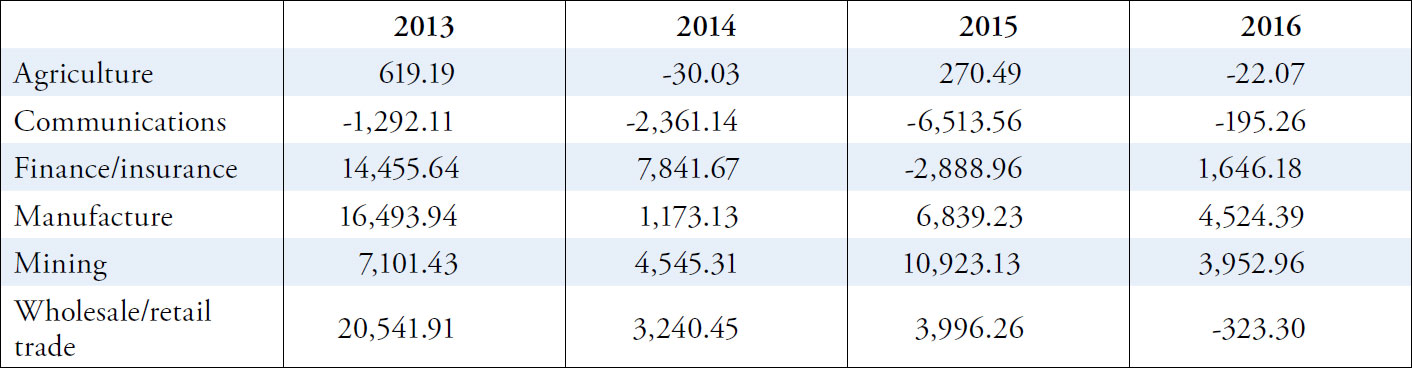

The relatively slow trickle of money into the agriculture sector is evident in Figure 2 and Table 2 respectively, which depict net FDI inflows into Russia by sector. As before, the figures for 2016 reflect only the first quarters of the year. The communications and construction sectors have also suffered under the latest crisis, as state funds have been cut back and large scale projects such as the Sochi Olympics completed. Late in 2016, news broke that IKEA, Leroy Merlin SA, and other high-profile retailers were ramping up investment to take advantage of improving consumer sentiment.4 That would reverse a trend of rapidly dropping FDI in that sector witnessed over the last several years.

Figure 2: Net FDI Inflows into Russia by Sector (mln. USD, 2013–2016*)

Table 2: Net FDI Inflows into Russia by Sector (mln. USD, 2013–2016*)

Russian mining and manufacturing are enjoying increased attention from foreign majors over the last two years. Royal Dutch/Shell and Rosneft have begun work, finalizing a $10 billion LNG project on the Baltic Sea, while BP has created its own joint venture Ermak Neftegaz, also with Rosneft, to explore oil reserves in Siberia. The decision to sell stakes in oil reserves held by Rosneft subsidiary Vankorneft to Indian firms also marked a concerted shift towards opening strategic assets to new types of investors.5 Finally, German companies have led the way in opening new manufacturing plants, particularly automakers such as Volkswagen and Mercedes-Benz, who have eyed Russia as an attractive place to produce cars for further export.

Another government-sponsored initiative to spur foreign investment, the much-heralded Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF), has had a rocky ride. Started in 2011 with backing from the Russian government, RDIF was designed to channel (and match) foreign investment to deserving projects that weren’t clouded by political connections or influence. The fund quickly brought on board top Western executives and went on the offensive in raising funds from both the private sector and sovereign wealth funds worldwide. But questions arose about how distant RDIF truly was from the government. Loans were being granted to companies with direct ties to President Putin, and some saw the body as operating as little more than a subsidiary of the controversial Russian state development bank Vnesheconombank (which in actuality it was). The U.S. government soon agreed and added RDIF to its sanctions list. Western investors consequently backed away.

Despite this setback, the RDIF has still managed to raise considerable funds from countries in Asia and the Middle East. Its list of partnerships is impressive, totaling over $25 billion of foreign capital. In July 2015, Saudi Arabia committed to investing $10 billion over the next five years in Russia, making it the fund’s largest country partner and surpassing China. Furthermore, Kuwait, Japan and India have announced commitments of $500 million in investment that would be matched by RDIF. It is too early to assess how well these partnerships have borne fruit, but the injection of this small but growing volume of foreign capital is a first step to reducing reliance on the EU and US.

Foreign companies also have not shied away from debt instruments as an avenue into the Russia market. In many respects, Russia was the first internationally sanctioned country that had been an active participant in international debt markets. Once the picture became clearer on how the economy would weather the multiple storms it faced, many investors were eager to pick back up where they left off wherever possible. Data from Bloomberg indicates that the syndicated loan market is heating up with significant offerings made to Russian majors. Companies such as Norilsk Nickel and Gazprom both helped restart the Russian Eurobond market in 2015,6 while the latter also secured a $2 billion loan from the Bank of China in early 2016. Even sanctioned firms such as Rosneft have gotten into the action by devising pre-payment plans to get around restrictions that no credit be extended beyond 30 days.7 Loan levels are still far off from the pre-sanctions period, but foreign investors appear to be gradually dropping their guard when it comes to lending to Russian firms.

Future Prospects

Investors have not soured on long-term growth prospects for Russia, in part because the boom times of the mid-2000s weren’t enough to satiate built-up Russian consumer demand. Above-average returns are hard to come by globally, and many investors are acclimating themselves to working in situations with heightened political risk such as Russia. Russian labor costs are also now relatively inexpensive given the prolonged drop in the value of the ruble. Geographic proximity to a number of critical markets with large growth upsides makes Russia an especially attractive place to build export-oriented production facilities. Large-scale investments made now will take years to come to fruition, and foreign firms may be hoping to time their completion with liberalization of the economy under a possible fourth presidential term for Putin.

Overall enthusiasm for jumping back into Russia though is still measured. The majority of foreign investors shy away from market volatility. Severe fluctuations in the ruble exchange rate, which is still closely tied to oil prices, can disrupt even investors’ best laid plans. Moreover, optimism over a grand reconciliation between Russia and the US under Trump has waned, as evidenced by the Russian stock market MICEX now having returned to November 2016 levels after a prolonged rally. Russia requires intensive foreign investment to upgrade technology and capital stock, improve productivity, and jumpstart economic growth. Although the Russian government has continuously made overtures and designed specific policies for foreign firms, only widespread institutional reform can reduce the risk involved with investing.

Notes

1 Pami Aalto and Tuomas Forsberg. 2015. “The Structuration of Russia’s Geo-economy under Economic Sanctions” Asia Europe Journal. 14 (2): 221–237

2 Tess Stynes. “Abbott to Acquire Russian Drug Maker Veropharm” Wall Street Journal. June 23, 2014. <https://www.wsj.com/articles/

abbott-to-acquire-russian-drug-maker-veropharm-1403556975>

3 ET Bureau. “Sun Pharma to Acquire 85 per cent Stake in Russia’s Biosintez” The Economic Times. November 24, 2016. <http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/healthcare/biotech/pharmaceuticals/60-million-deal-sun-pharma-toacquire-russian-company-jsc-biosintez/articleshow/55576458.cms>

4 Ilya Khrennikov. Big Western Companies Are Pumping Cash Into Russia. Bloomberg. November 22, 2016. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-11-23/bouncing-backputin-s-shrunken-economy-lures-foreign-investors>

5 Nicholas Trickett. “Russia Strengthens Energy Ties With India” Global Risk Insights. October 28, 2016. <http://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/Russia-Strengthens-Energy-Ties-With-India.html>

6 Lyubov Pronina. “Gazprom Follows Norilsk Nickel With Russia’s Second Eurobond.” Bloomberg. October 8, 2015. <https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-10-08/gazprom-follows-norilsk-nickel-with-russia-s-second-eurobond>

7 Neil Hume and David Sheppard. “Trafigura Becomes Major Exporter of Russian Oil”. Financial Times. May 27, 2015. <https://www.ft.com/content/93a4a466-048b-11e5-95ad-00144feabdc0>

About the Author

David Szakonyi is Assistant Professor of Political Science at the George Washington University.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.