Industrial-Scale Looting of Afghanistan´s Mineral Resources

8 Jun 2017

By William A Byrd and Javed Noorani for United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageUnited States Institute of Peace (USIP)call_made in June 2017.

Summary

- Afghanistan is well endowed with underground resources, but hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of minerals are being extracted yearly, unaccompanied by payment of applicable royalties and taxes to the state.

- The bulk of this industrial-scale mineral looting—which has burgeoned over the past decade—has occurred not through surreptitious smuggling but openly, in significant mining operations, with visible transport of minerals on large trucks along major highways and across the Afghan border at a few government-controlled points.

- The prior political penetration of power holders and their networks in government, who became increasingly entrenched over time, explains this pattern of looting, which is engaged in with impunity owing to massive corruption of government agencies charged with overseeing the extractives sector, main highways, and borders.

- The current political and security climate favors continued and even further increased looting, which strengthens and further entrenches warlords, corrupts the government, partly funds the Taliban and reportedly ISIS, and fuels both local conflicts and the wider insurgency.

- Although the situation is dire and no answers are easy, near-term recommendations that could begin to make a dent in the problem include halting the issuance of new mining contracts, enforcing existing contracts to ensure taxes and royalties are paid, monitoring the transport of minerals on main roads and across borders, and imposing an emergency levy on mineral exports.

- The recent appointment of a new minister of mines is a good step forward, but a well-functioning, effective ministry management team will be key to success.

- Over the medium term, a political consensus is needed that part of the proceeds of mineral exploitation goes to the government budget and that ownership arrangements of mining companies are transparent. In addition, a system of monitoring flows of some Afghan minerals outside the country—as conflict minerals—should be considered.

Introduction

Afghanistan is well endowed with mineral resources. In addition to significant oil and gas reserves in the north (not discussed in this report) and a few mega-resources (Aynak copper and Hajigak iron, also not covered), there are numerous medium-sized and smaller deposits of minerals such as precious gemstones (notably emeralds and rubies), gold, silver, coal, chromite, marble, granite, talc, and nephrite. Afghanistan is uniquely endowed with reserves of lapis lazuli, a semiprecious colored stone considered the country’s signature mineral. Artisanal exploitation of small, scattered mineral resources typically has occurred on an informal basis. Artisanal extraction is not a focus of this report.

Though the mega-resources remain untapped, mineral extraction from medium-sized and smaller mines has burgeoned in recent years and is occurring at what can appropriately be called an industrial scale. Unfortunately, it is generating only negligible taxes and royalties for the Afghan government, largely negating any benefits for national development. Moreover, such resource exploitation benefits and strengthens the power of warlords, corrupts the government and undermines governance, partly funds the Taliban and reportedly ISIS as well, and fuels both local conflicts and the wider insurgency.

It is striking that these activities, which for the most part are engaged in by registered companies holding contracts issued by the Afghan government for mining purposes, are both visible and potentially monitorable. Unlike surreptitious extraction and smuggling, mining on this scale entails significant operations and is conducted openly, with the minerals being transported on large trucks along major highways and exiting Afghanistan at just a handful of government-controlled border crossing points. The Afghan government should be able to exert control over these activities and receive state benefits in the form of stipulated royalties and taxes paid into the national coffers, but it does not.

Hence the central question addressed by this report is, why not? The second question is, what can be done about this dire situation? The report puts forward a conceptual framework and presents brief case studies of selected minerals to provide a basis for answering the first question. There are no simple answers to the second question—on the contrary, there are grounds for pessimism based on the analysis provided here. Nevertheless, the report ends with some fairly drastic recommendations that, if implemented, would provide some hope for containing and, over time, rolling back this scourge on Afghanistan’s politics, governance, security, and development.

Minerals Ownership and Mining Contracts

Under the national constitution, Afghanistan’s underground minerals belong to the state. In principle, legal mining activities can occur only under a contract issued on behalf of the state by the Ministry of Mines and Petroleum (MoMP). Royalties are negotiated separately for each contract and are specified in the contract, though some broad guidelines for different minerals are in place. In addition, mining enterprises, like other businesses, are required to pay tax on their profits, in accordance with the country’s income tax law. The MoMP is supposed to monitor royalty payments, whereas corporate profit tax is under the purview of the Afghanistan Revenue Department, and export licenses and fees are handled by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry (MoCI).

Mining contract provisions for the most part are not observed, however, and substantial commercial exploitation often occurs during the exploration phase (which is frequently extended), with negligible payment of royalties and taxes to the government. Abuses occur in a variety of ways and at all stages of the process: in the issuance of tenders (often skewed in favor of certain parties), in reviewing and shortlisting applications received (subject to political influence), during the bidding process and bid evaluation (winning bids are often based on highly unrealistic promises of royalties), through bypassing the legal prohibition against political leaders and government officials engaging in mining activities, through failure to conduct environmental and social impact studies or to observe mine safety regulations, through abuse of the exploration period for commercial exploitation, in ex post changes in contracts to the benefit of the company concerned, and in failure to deliver stipulated royalties to the state or to pay profit tax on mining activities.

Mining companies that obtain contracts tend to be owned by politically connected persons, including, in many cases, members of the Afghan parliament (MPs), their family members, their associates, and power holders with access to armed groups and their networks. The beneficial ownership of mining companies—that is, who shares in the profits—tends to be hidden, particularly when shareholders are persons not allowed under law to have a contract with the government (as is the case for MPs). These ownership patterns conveniently enable power holders and their networks to share in the proceeds of mineral extraction while denying the government taxes and royalties payable under the contracts.

The rampant extraction and export of minerals likely amounts to well into the hundreds of millions of dollars per year, but government revenues from the country’s mineral resources have been very small, with royalties accruing to the MoMP amounting to only Afs 1.1 billion ($16 million) in 2016. Thus looting is a correct description of most of the mineral exploitation currently occurring in Afghanistan, and it has burgeoned to the point—thousands and tens of thousands of tons annually, and in some cases even more—that industrial-scale looting is an appropriate characterization.

Lootable Resources: Definition and Implications

The word loot, in verb or noun form, entered the English language toward the end of the eighteenth century from Hindi; its origins can be traced back to Sanskrit. In the dictionary definition, to loot means to steal, plunder, or take by force. In this report, when we talk about the looting or industrial-scale looting of Afghanistan’s mineral resources, we are using this conventional, commonly understood definition of the term.

The report also uses the term lootable, which carries a technical definition in the academic and policy literature on resource exploitation and makes an important distinction between lootable and nonlootable resources. Lootable gained widespread currency when it came to be used in reference to minerals that could be plundered easily and used to finance armed groups or to corrupt and undermine governments; an example is so-called conflict diamonds in Africa.

Richard Snyder lists four elements, the first two of which are essential, the second two of which frequently occur, that make for a lootable resource:

- Low economic barriers to entry and relative ease of extraction. An example is alluvial diamonds, for the extraction of which “a pick, shovel, sieve, and sweat” are all that is needed.

- Low bulk. Lootable resources are easy to transport, conceal, and smuggle, making the value-to-weight ratio high enough that small-scale transport by surreptitious means is profitable.

- Geographic dispersion. Many lootable resources are found in widely scattered locations in remote areas.

- The illegality of some lootable resources. Illicit opium and opiates are a notable example.

Snyder asserts that, having these characteristics, lootable resources are not amenable to purely public-sector extraction, by the national government and its entities. Instead, what he terms private extraction—that is, extraction by local actors—is the norm. He further posits that, through a combination of incentives and threats, the government may be able to pressure local actors into engaging in some form of joint exploitation whereby the government shares in the proceeds of extraction. Conversely, nonlootable resources, or those lacking the characteristics that define a lootable resource, are amenable to public extraction. The anomaly in Afghanistan is that resources that would be considered nonlootable by Snyder’s criteria are subject to massive looting outside government control.

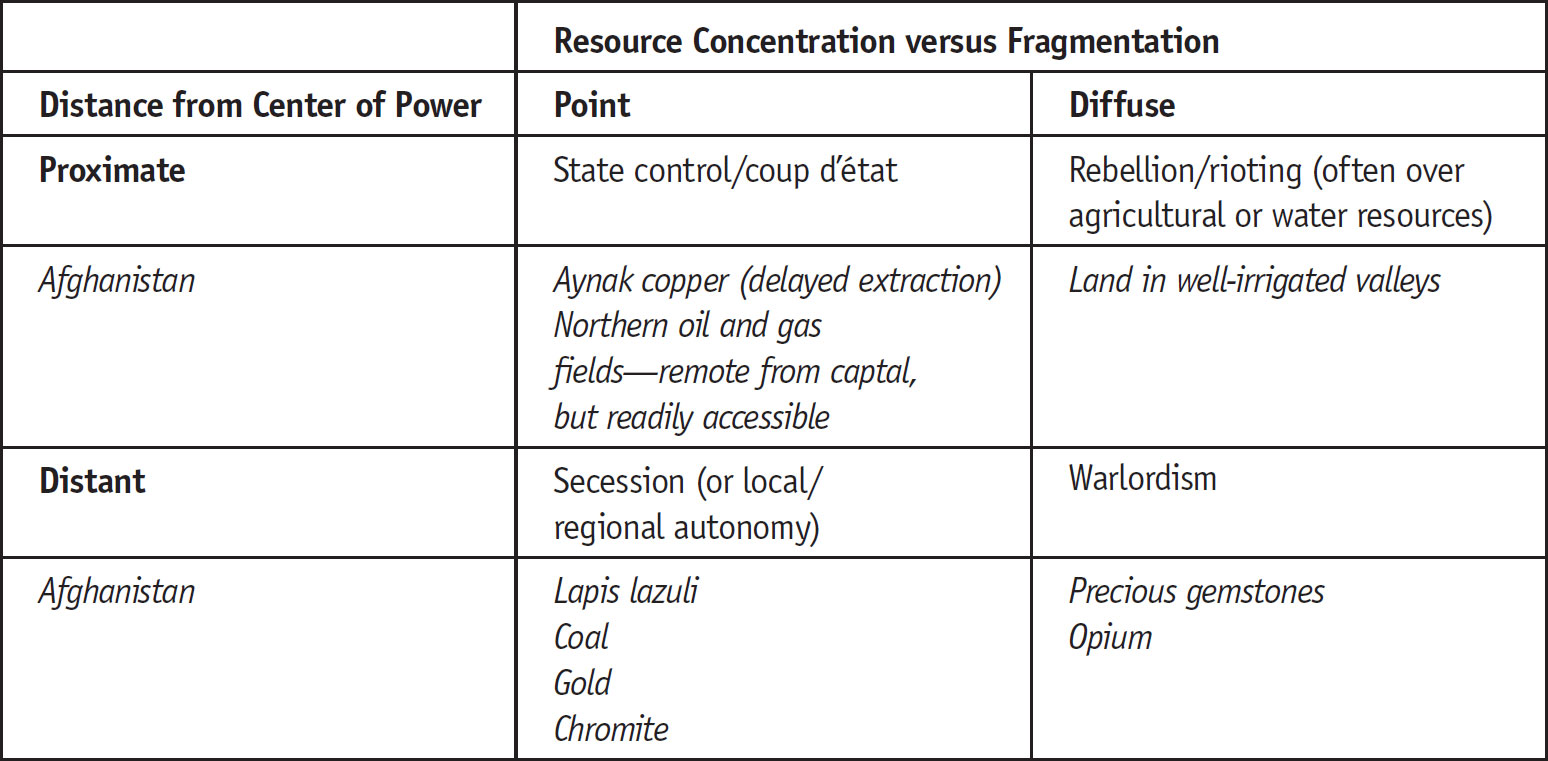

Philippe Le Billon provides a conceptual framework for analyzing natural resources and conflict based on a twofold geographic categorization of resources: point (concentrated) versus diffuse (scattered widely) and proximate (to the center of power) versus distant (remote). Table 1 shows this two-by-two mapping, illustrated with selected Afghan mineral resources.

Linking this table to Snyder’s definition of lootability, the mineral resources in the lower right quadrant (scattered, distant from center of power) can be characterized as lootable, whereas those in the upper left quadrant (point source, proximate to center of power) are nonlootable. Resources in the lower left quadrant (point source, distant from center of power) for the most part would also be nonlootable, though scattered point deposits of easily extractable, high-value minerals would be lootable. The upper right quadrant also appears to hold largely resources that are not easily lootable.

Following Le Billon’s analysis, different types of conflicts can be aligned with various quadrants in the two-by-two table. Given the lack of serious secessionist movements in Afghanistan’s history, conflicts generated by resources in the lower left quadrant (point concentration, distant from center of power), should be expanded beyond outright secession to include conflicts aimed at furthering regional and local autonomy but falling short of attempts to split up the country. Resources in Afghanistan that are distant from the center of power, whether point source or scattered—those represented by the lower half of the table—may generate funding for Taliban and other antigovernment elements that, beyond regional or local autonomy, are also contesting for control of the country. Interestingly, proximate point resources (top left quadrant) and proximate but diffuse resources (top right quadrant) have not been the most salient sources of conflicts in Afghanistan. Finally, warlordism is an apt characterization of many extraction arrangements and associated conflicts in Afghanistan, certainly those in the lower right quadrant but also others.

Expanding upon this conceptual framework leads to two additional important points. First, resources that are lootable in small quantities may become nonlootable (in Snyder’s definition) when large amounts are concerned, since the extraction, transport, and export of large quantities inevitably involve very visible activities. Lapis lazuli is a good example.

Second, whether a mineral resource should be considered lootable in Snyder’s definition may vary across stages of the supply chain, from extraction to processing (if any) to transport and eventually export. If a mineral is nonlootable at even one stage, it arguably must be assessed as nonlootable overall. Specifically, some resources may be lootable at the point of extraction but not at the processing stage (if significant technology and capital are required) or at the transport and export stages (for example, if transport by large trucks is occurring on a few main roads and through only a couple of government-controlled border crossing points).

Mineral Looting in Afghanistan

Although a comprehensive discussion of mineral looting in Afghanistan is beyond the scope of this report, selected examples—chromite, gold, coal, talc, nephrite, rubies and emeralds, and lapis lazuli—are briefly reviewed.

Chromite

This mineral, composed of chromium, iron, and oxygen, is the only commercially extractable source of pure chromium, commonly known as chrome. Chrome is one of the most important and indispensable industrial metals because of its hardness and resistance to corrosion.

Rich chromite resources are found in Parwan, Logar, Maidan Wardak, Nangarhar, and Kunar provinces. Chromite earlier was illegally extracted and transported out of the country, especially from Kunar, which lies on the Pakistan border and has convenient smuggling routes. This extraction from Kunar was stopped in 2012 when the Afghan government confiscated machinery being used for chromite ore crushing and warned a leader of the Afghan Local Police to end these operations, which he had been engaged in.

More recently, private operators elsewhere have been extracting chromite under exploration licenses from the MoMP. Five such contracts were awarded for mines located in the Dadu Khel area of Mohammad Agha district of Logar province, Lalandar district of Kabul province, the Gadaha Khel area of Parwan province, Goshta district of Nangarhar province, and in Maidan Wardak.

All of these contracts appear to have been awarded to MPs or their associates. The mine in Goshta district reportedly is under the control of a sitting MP, who reportedly has been extracting chromite since 2010. He is alleged to be operating through his nephew and to be collaborating with local elders and the Taliban, whom he reportedly pays off. More recently he is said to have created his own Afghan Local Police unit and to be tolerating a group of Taliban around the mine to create the impression that the project area is insecure so that he can continue to extract freely. The chromite mine in Dadu Khel reportedly is controlled by another sitting MP. He has been exploiting the mine under an exploration license and exporting chromite ore by the truckload. In addition, fifty-two smaller chromite sites in Logar province are being illegally exploited, the chromite leaving the country through the border point in Khost province into neighboring Pakistan. Another sitting MP controls a chromite mine in Parwan and has been extracting chromite under an exploration license from day one. He reportedly has extracted more than 120,000 to 140,000 tons of chromite to date without making payments to the state. The chromite mine contract in Maidan Wardak has been awarded to a politically connected person who had earlier exploited a chromite mine in Khost and was caught smuggling chromite through the Khost border checkpoint. Nevertheless, he now holds four mining contracts: two salt, one gold, and the Maidan Wardak chromite.

All in all, companies have extracted large amounts of chromite under exploration licenses, transported it along national highways in large trucks, and exported it (with bribes paid to police and border officials). So this resource as it is currently being exploited must be considered nonlootable in Snyder’s definition, though it is obviously being looted.

Gold

Afghanistan has deposits of gold in several provinces, such as Badakhshan, Baghlan, Takhar, Herat, and Ghazni; recently gold-bearing areas have been identified in Maidan Wardak and Kabul provinces. In the past, artisanal gold extraction occurred in Badakhshan, Baghlan, Ghazni, and Takhar provinces.

Gold deposits at Qarazaghan in Doshi district of Baghlan were discovered in the 1980s and gold was extracted by an important local notable until the Taliban captured Baghlan in the 1990s and confiscated his machinery, moving it to Kandahar. After the downfall of the Taliban regime in 2001, the notable’s son resumed extraction. In 2011, apparently through political connections in the government, he secured a mining license. The company reportedly extracted gold under its exploration license (initially granted for two years and subsequently extended for another two years), without paying royalties or other taxes to the state. The company eventually denied finding any gold and managed to cancel the contract with the government even though Dusko Ljubojevic, a South African geologist working for another company, is reported as saying in 2011 that there was exploitable gold in the mine.

The Nuraba and Samti Gold Mine in Cha Ab district of Takhar was in 2008 contracted to a company that had previously had a contract for mining chromite in Khost, which it reportedly misused to extract chromite during the exploration stage and smuggle it out through Waziristan. The Nuraba and Samti contract was renegotiated in 2013. Not only were the contract terms softened, the company was also not pursued for payment of past dues. It first extracted gold during the exploration phase, and such activities continue. Despite extracting gold worth millions of dollars, the company is not yet covered under Afghanistan Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (AEITI) reporting on mining revenue going to the government, strongly suggesting that no significant royalty or tax payments have been made.

Gold presents a mixed picture with regard to lootability: significant reserves conventionally mined are nonlootable in Snyder’s terms (because of the extensive processing required for gold ores), whereas alluvial gold in rivers and streams is lootable, and smuggling small quantities of gold surreptitiously is feasible and profitable.

Coal

Afghanistan has widespread deposits of coal across the country, contrary to earlier views that coal resources exist only in the north. Coal is considered a nonlootable resource because it requires sizable operations to extract in quantity and is a bulk commodity transported by truck in large loads.

Coal deposits in the north and west of Afghanistan have long been mined, sometimes under license but often illegally by power holders, MPs, and other politically connected people. The most heavily looted coal deposits are in Dan-e-Toor and Garmak districts of Samangan province. According to a list of illegal mining sites across the country, there are more than 350 coal extraction sites in these districts. One author personally visited the Dan-e-Toor region, where he found about a hundred coal tunnels, all for illegal extraction. A senior MoMP official admitted that five MPs collectively were operating 892 coal tunnels and extracting thousands of tons of coal daily. Coal deposits in Sar-i-Pul, Takhar, and Bamiyan provinces also are being illegally mined and the coal supplied to brick kilns or exported to Pakistan.

Another MP, elected from Herat province, is operating two coal mines through his company, one in Herat and the other in the Western Garmak district of Samangan. He has reportedly been extracting large amounts of coal and exporting most of it to neighboring countries but does not pay royalties or taxes.

Yet another example is the Afghan Investment Company (AIC), created by Mahmud Karzai, Haseen Fahim, and more than thirty other businessmen to rehabilitate the formerly publicly owned Ghori Cement plant. Initially the AIC was allowed to extract up to one million tons of coal per year on highly favorable terms with the understanding that it would be used as raw material for AIC’s cement plants. Later on, two more coal deposits were awarded to the AIC. The contract for coal initially was part of the main Ghori Cement contract, but later it was separated from the cement contract, and the AIC was allowed to extract and sell coal on the open market, without an increase in the extremely low royalty rate. The government apparently has not been receiving the requisite amount of royalties. According to the AEITI report for 2013, the AIC paid Afs 56.65 million in royalties that year (around $1 million), whereas according to the contract, $8 million in royalties should have been paid for extracting one million tons of coal per year.

Trucks carry coal along major highways, which in many places are under government control, without meaningful monitoring or oversight. One author on two occasions personally counted hundreds of trucks full of coal freely passing through Kabul on the way to their destination abroad. Pakistani trucks transporting goods to Central Asia and Afghanistan on their return transport coal at half the price Afghan trucks would charge, since otherwise these trucks would be returning empty. Moreover, empty trucks take up to seven days to be cleared at the border, whereas loaded trucks are cleared within a day, providing further incentive to transport coal.

Although no accurate data are available on total coal extraction and exports, based on observation of extraction points and field research in some major mining areas in Herat, Samangan, Takhar, Baghlan, and Bamiyan, the total extraction of coal can conservatively be estimated at roughly three to four million tons a year, with an aggregate value in the range of $300 million to $400 million.

Talc

This mineral (hydrated magnesium silicate) has a wide range of industrial uses. Sherzad and Khogyani districts in Nangarhar province are known for their world-class talc deposits. Talc has been extracted by local residents and mine operators and exported to Pakistan, from where it is further exported to Italy, Saudi Arabia, France, and Japan, according to one talc trader. Though several licenses were issued to private companies for talc extraction, these companies, all politically connected with MPs or local power holders, grossly overextracted talc, violating the terms of their licenses; underpaid the government; and made payments to the Taliban. Mine operators in Sherzad district reportedly pay $10 to local officials per ton of talc and $12 to the Taliban. Any private company operating a talc mine needs to pay “rent” to the Taliban and reportedly in some cases to ISIS as well.

The supply chains for Afghan talc between Nangarhar and international markets are described in two articles in Le Monde. At the downstream end, the large French company Imerys—which mines and sells minerals, including talc, worldwide—established a relationship with and purchased talc from a Pakistani company for onward export to Europe and the United States. Afghan talc purchased by Imerys reportedly had reached twenty thousand tons by 2012 and rose further to thirty-nine thousand tons in 2014. Prices reported separately in the Le Monde articles would indicate values in the range of $3 million to $5 million and $6 million to $9 million for the years 2012 and 2014, respectively.

Le Monde also reports on another supply chain leading through a different Pakistani company to the Italian company IMI FABI. Exports by this Pakistani company reportedly surpassed one hundred thousand tons in 2014, worth at least $15 million, before declining precipitously in 2015 because of an export ban imposed early that year.

Concerned about the uncontrolled exploitation of talc and associated funds going to the Taliban, the Afghan government declared a blanket ban on the extraction and export of talc, precipitating a sudden disruption of supply across the border and a build-up of talc stocks in Nangarhar. According to an MoMP official who personally inspected stocks of talc, about 375,000 tons were piled up in Sherzad district alone. Estimates of the total amount of talc stockpiled after the ban were as high as 750,000 tons, worth perhaps $40 million within Afghanistan.

Under pressure from downstream purchasers to continue to supply high-quality Afghan talc, interested parties reportedly had to pay senior provincial and Kabul officials to arrange a one-time permit for export of the accumulated stockpiles of talc, and an export permit for one hundred thousand tons was secured. But then foreign and Afghan talc traders reportedly exported perhaps as many as a million tons of talc, far in excess of the permitted amount. Despite the ban, talc extraction reportedly is ongoing in Sherzad, Khogyani, and Achin.

Senior officials of the provincial mining department admit that most of the talc-rich districts of Nangarhar have come under the influence of the Taliban or ISIS. Residents have complained that the Taliban and ISIS may have started to engage in direct extraction of talc. Local elders recently stated that “the Taliban shadow governor of Nangarhar province visited the talc mines in Sherzad district to assess them, and NATO aircraft bombed his location, but he managed to escape unhurt, though several Talban died. In Achin district of Nangarhar, ISIS reportedly had taken control of talc and was directly extracting and selling it to traders.”

Talc is a low-price bulk commodity typically priced at around $200 per ton when exported from the region and less than half that within Afghanistan, and therefore does not meet Snyder’s criteria for lootability. It is being looted on an industrial scale because of lack of security at mining sites and the pervasive corruption that allows talc to be transported on government-controlled roads and through the international border checkpoints. As security has deteriorated in Nangarhar and both the Taliban and ISIS have made some gains, not surprisingly they increasingly share in the benefits from talc looting. However, as a bulk commodity with significant transport costs, the profit margins for talc are lower than for higher-value minerals, providing less scope for extortion, rents, and payoffs.

Nephrite

Nephrite, a form of jade, is much prized for stone carvings and jewelry, especially in China. It is a strategic material that is very hard and has high resistance to heat. Afghanistan has nephrite deposits in Kunar, Nangarhar, Nuristan, Kabul, Logar, Badakhshan, and Parwan provinces, with potential in other areas as well. Illegal extraction reportedly is occurring in all these provinces. Siberian nephrite had been considered world-famous, but Afghanistan, whose nephrite was introduced to the world market three years ago, is seen to have the potential to yield even better-quality stone.

A blatant case involving nephrite is found in Goshta district of Nangarhar province, home of an extensive deposit that stretches to Khas Kunar district of Kunar province. A sitting MP reportedly has been extracting significant amounts of nephrite from Goshta for the past three years with no contract, and smuggling it out of the country through Gandaw and Torkham. Earlier he reportedly paid 15 percent tax to the Afghan Taliban and 15 percent to the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, but now he is alleged to be paying 15 percent to members of ISIS as well, to allow him to transport the nephrite out. ISIS reportedly has begun to extend its control to the nephrite mines themselves, and to be extracting jasper from the same district.

Another nephrite mine, between Kohi Safi district of Parwan and Tagab district of Kapisa, is in territory under the control of the Taliban but is operated by local people. A local resident spoke of an agreement with an Afghan trader to supply nephrite from the mine. When the trader came for the first time, he paid $10,000 to the Taliban plus $1,000 for every ton of nephrite extracted from the site.

Overall, it appears that tens of thousands of tons of nephrite are being smuggled out of the country every year, though variation in the quality of nephrite makes it difficult to estimate the total value.

Precious Gemstones (Emeralds and Rubies)

Afghan gemstones have been extracted in small amounts for millennia. Among the gemstones, rubies and emeralds have been increasingly exploited in recent decades. These are eminently lootable resources because they are remotely located, easy to extract, and profitable to transport surreptitiously in small amounts.

Well-known deposits of rubies are found in Badakhshan province and in the Jegdalek area of Sarobi district of Kabul province. Local people in both areas have extracted rubies using artisanal techniques for decades. The locality where rubies are found in Jegdalek is currently under Taliban control, but miners can work, and reportedly pay about 10 percent “royalty” to the Taliban. Local police in the district also are said to take a 10 percent cut from whoever passes through. As noted in a 2012 BBC report on ruby mine plundering, “Tribal elders say that…the mines are being plundered by thieves, corrupt officials and the Taliban.” According to a police officer who accompanied the BBC journalists on their visit, “The Taliban tell the locals to work here.…They tell them: ‘We will give you 25% of the profit on the rubies you bring.’ The best rubies are on Taliban’s side of the mountain. Every Friday the Taliban organize a ruby bazaar near Jegdalek....Here they sell rubies which are then smuggled to Dubai, Pakistan and Thailand.”

Extraction has increased manyfold in recent years. Demand for Afghan rubies appears to have increased at least in part because new buyers use them to launder their illicit money. Terrorism may be another factor contributing to increased demand, because terrorists can use gemstones to transfer financial resources from one area to another unnoticed.

Emeralds were discovered in the Khenj district of what is now Panjshir province in the 1970s. No official or public records of emerald production in Panjshir exist; however, according to some reports, Commander Ahmad Shah Masood, leader of the anti-Soviet resistance, estimated that approximately $8 million worth of rough emeralds were extracted in 1990. A member of his circle is quoted in a report as mentioning emeralds as a source of revenue for the group.

Emerald mines in Panjshir are under the control of provincial elites. Extraction is illegal but widespread, even though the province is peaceful and secure. Miners are said to pay a 10 percent royalty to the provincial government, but these monies reportedly do not reach the central government. Local people engaged in mining have no official contracts; they reportedly just inform the district administration before they start.

Emerald miners are said to have powerful patrons in Kabul. An emerald trader confided that the brother of the deceased former vice president of Afghanistan is operating a mine and buys the best-quality emeralds and has them taken out of the country. This belief is echoed by several gemstone traders in Kabul. Sources indicate that MPs and commanders are involved. A long-established company, owned by a former associate of Commander Masood, has long dominated the purchase, sale, and export of emeralds from the province, reportedly without paying royalties or taxes to the government.

Often small ruby and emerald consignments are taken out through Kabul airport. Some traders and transporters are reported to greatly undervalue their shipments of rubies or emeralds and to pay minimal royalties, while others bribe officials of the MoMP so that they can easily take the emeralds out of the country. Many traders hide small amounts of emeralds or rubies in their luggage and take them out that way. A more recent trend is the use of courier companies to send gemstones to any destination.

Lapis Lazuli

Afghanistan is uniquely endowed with reserves of lapis lazuli, located in the remote Kuran wa Munjan district of Badakhshan province in the country’s northeast. In the years prior to the late 1970s, extraction was under strict government control and was limited to four tons per year. Prices tended to be high, and significant processing of lapis occurred within Afghanistan, for lapidary and jewelry purposes. During the resistance against the Soviet occupation (1979–89), the subsequent Najibullah regime (1989–92), and the civil war and Taliban regime (1992–2001), lapis lazuli was continually extracted by mujahideen resistance forces and smuggled out of Afghanistan. In addition to funding war costs, the sale of lapis helped enrich key commanders.

After the downfall of the Taliban regime in late 2001, lapis extraction continued and has increased markedly in recent years. Two groups of power holders and their networks, one associated with former president Karzai (including a key figure heading the local unit of the Mine Protection Force, part of the national police force), the other with the former Northern Alliance (which controlled armed militia groups in the mining area), contended for control of the lapis mines and associated lucrative revenues. Violent conflicts broke out in 2011, 2012, and most notably in January 2014 when the Northern Alliance took over the mining area by force. In 2013 a contract was awarded to a mining company associated with the faction linked to Karzai. However, this company did not engage in extraction but merely collected a fee from others who were exploiting lapis. After the change of government in 2014, in a sharp reversal of policy, Afghanistan’s National Security Council banned extraction and suspended the company’s contract in early 2015, subsequently ordering cancellation of the contract in December 2015. This left the way open for the faction associated with the former Northern Alliance to continue illegal extraction. Punctuated by episodes of organized violent armed conflict, there have also been periods of fragile truce and de facto cooperation among the different actors involved.

The sheer magnitude of lapis extraction in recent years has been striking. It is estimated to have peaked in the six thousand to eight thousand metric tons range in 2014 before declining to around four thousand to five thousand metric tons in 2015. Recent production is more than one thousand times the prewar level and an order of magnitude greater than during the civil war and early post-2001 period. Estimating the value of this production is challenging; crude numbers for 2014 range from $80 million to $270 million, with somewhat lower estimates for 2015.

The transport of lapis beyond the mining area to and through the border occurs on large trucks carrying loads of as much as twenty-five to twenty-eight tons. The trucks move along Afghanistan’s main national highways and pass through or close by Kabul. The export of lapis occurs predominantly through the official Torkham border crossing between Pakistan and Afghanistan. Thus the case for considering lapis at current levels of exploitation nonlootable (in Snyder’s definition) is overwhelming. The lion’s share of lapis exports goes to China, where prices have collapsed because of oversupply.

Looting of Nonlootable Resources in Afghanistan: How and Why

Most of these minerals, at current scales of exploitation and at one or more stages of their supply chains within Afghanistan, must be considered nonlootable according to Snyder’s definition. Only precious gemstones (exemplified by rubies and emeralds) are truly lootable at all stages, from their point of extraction through the border of Afghanistan. Gold ores, in contrast to alluvial gold, which is found in rivers and streams, require significant processing, typically at or near the mine site; hence gold cannot be considered lootable at that point in the supply chain. All of the other examples—lapis lazuli, coal, chromite, talc, and to a large extent nephrite—are transported in heavy loads weighing tens of tons on large trucks that have to stick to the main paved highways as they traverse significant distances, and are exported through the handful of border crossing points served by such roads. This means that the transport and export of such minerals are visible to government agencies and cannot be surreptitious. Thus these minerals cannot be considered lootable (by Snyder’s definition) at these points of their supply chains. Moreover, the sheer scale of exploitation of a number of Afghan mineral products, most notably lapis lazuli but also others, means that they cannot be considered lootable at the extraction stage, either.

Why, then, is the dominant pattern private exploitation, with negligible revenues accruing to the Afghan government? Why is there not more public-private joint exploitation or at least sharing of the proceeds of mineral extraction, or even, in some cases, public exploitation (as was the case with lapis lazuli before the past nearly forty years of conflict)?

One partial explanation that could be advanced relates to the remoteness of many of these resources and the limited reach of the government into far-flung parts of the country. This may have some superficial plausibility, but it does not address those segments of supply chains (most notably transport by large trucks on highways and crossing the border at a few border points) where the national government does have an institutional presence and its security forces are in control. Moreover, some of the point-resources are large enough that it would be in the national government’s interest, and within the capabilities of its security forces, to exert control over the mining sites.

Based on the evidence from fieldwork and case studies, a different explanation is far more compelling. The post-2001 Afghan government from the time of its formation has been politically penetrated by networks of power holders—actors with their own access to the means of organized armed violence—whose members are involved in, or at least benefiting from, ongoing mineral exploitation. These networks, which had formed and developed during the resistance against the Soviet occupation and the subsequent civil war, were largely defeated by the Taliban regime in the mid- to late 1990s. They came back into power with the fall of the Taliban in late 2001 and have become increasingly entrenched politically. These individuals and networks essentially have formed the political base of the post-2001 government, and despite successive election cycles and the rebuilding of the government administration, they remain for the most part largely unchallenged.

This involvement of powerful networks goes beyond transactional hand-shake corruption and extends to the embedding of their associates and interests within the government. Thus the ongoing looting of resources that are nonlootable according to Snyder’s definition is possible because key nodes of potential government control—during the contracting process, at the point of extraction, during transport and (if applicable) processing, and at border crossings—are co-opted by those engaged in the looting through their networks, preventing the government from enforcing joint public-private or public exploitation of the resources concerned.

Thus the organization of industrial-scale looting in Afghanistan is different from what Le Billon’s and others’ analyses would predict because of path dependence. Networks of power holders were entrenched in the post-2001 government before the industrial-scale looting of most mineral resources became prominent (though smaller-scale exploitation of some minerals had been occurring for several decades). Hence the power networks have been able to exploit opportunities in the extractives sector on an essentially private basis, lubricated by pervasive corruption entailing payments to political leaders, their associates, police and border officials, and connected government bureaucrats. The government, already co-opted by power holders and their networks, has been unable to prevent large-scale looting of nonlootable resources, or even to share in the profits to any significant degree. In this context, mining contracts issued by the government have effectively constituted licenses to loot, with no or negligible payments of royalties and taxes.

Dynamic considerations also have favored increasing industrial-scale looting. Such looting strengthens the financial and thereby the political base of power holders, and hence they tend to become even more entrenched over time, further enhancing their capability to engage in industrial-scale looting. All this potentially leads to a vicious cycle of increasing entrenchment of these power holders and their networks and ever-increasing looting.

Why has mineral looting burgeoned during the past decade, both in the latter years of the Karzai administration and more recently, during the tenure of the National Unity Government (NUG), to the point where calling it industrial-scale looting is appropriate? Beyond the financial and power dynamics outlined, several contributing factors may be involved, though assessing their roles and relative importance inevitably is a somewhat speculative endeavor.

Declining lucrative benefits from other activities in recent years—in particular from international military contracts, aid contracts, and other business activities associated with the enormous money flows into Afghanistan—may have been a significant push factor encouraging networks of power holders to shift into extractives. For example, a number of Afghan mining concerns had previously been construction companies, getting most of their business from international contracts until these fell off sharply during the transition with the drawdown of foreign combat troops and the phasing out of related international expenditures. The post-2001 political system thrives on various “rents” supporting the financial interests of different power holders and funding their political and security expenditures; reductions in one kind of rent may well push the political system to increase rents in other spheres of activity.

The high profits that can be relatively easily obtained from mineral looting constitute a strong pull factor attracting interest groups into the mining business. These profits have become progressively more accessible as experience is gained, markets are identified and exploited (for example, lapis in China, talc in Europe), transport channels open up, and business linkages are developed. Such dynamics can result in snowballing of extraction over time, as has occurred in the case of lapis, talc, and apparently chromite, among others.

The fragmentation of the NUG may constitute another enabling factor, along with ethnic and group-based fragmentation more generally. The Karzai administration, cobbled together from among various power holders and interest groups, was far from unified and was marred by increasingly widespread corruption. However, the polarization of the NUG between its two wings, tensions within each side, and worsening ethnic divides more generally may have further justified and encouraged mineral looting.

Though not normally relevant for extractive industries (sizable mining investments typically have long gestation periods and time horizons), intensifying short-termism may to some extent have contributed to the accelerated mineral looting seen in recent years. This looting has involved basic mining techniques (even when mechanized), minimal processing in most cases, and truck transport out of the country; thus relatively limited and short-term investments could reap large profits fairly quickly. Time horizons in Afghanistan shortened with the approach of the 2014 presidential election and its drawn-out denouement, plagued by uncertainty; after the U.S. announcement of a termination date for combat operations by the end of 2014 and complete troop withdrawal by the end of 2016 (subsequently rescinded); and with the progressively deteriorating security situation, compounded by the fragility, uncertainty, and short time horizons associated with the NUG itself (in particular as the next presidential election, now only two years away, draws near).

Unfortunately, the incentives and dynamics all seem to favor more, not less, industrial-scale looting. When such looting becomes significant in relation to the global market, most notably in the case of lapis but also other resources, steep price declines reflecting market saturation resulting from the large quantities coming out of Afghanistan may discourage further expansion of or even a slowdown in large-scale looting. However, market saturation may only slow, not stop, industrial-scale looting. Moreover, market saturation may well lead to shifts to other, more profitable minerals rather than to a net reduction in mineral looting overall.

Recommendations

In light of the entrenchment (politically, economically, and in the administration) and clout of individuals, groups, and networks associated with the industrial-scale looting of Afghan minerals, as well as the unfavorable dynamics of the Afghanistan context and the current fragile political situation and deteriorating security environment, there are no easy answers. Nevertheless, the following actions, tailored to the Afghan context, may make a difference in the near term.

Put in place a quality, cohesive, and effective leadership team in the MoMP, with the political space to carry out urgently needed reforms. This is a prerequisite for other improvements to be effective and sustainable. The recent appointment of a new minister is a good step forward, but a well-functioning, effective management team in the ministry is key to success.

Temporarily stop issuance of new mining contracts. Mineral looting often increases sharply after a government contract is issued, which appears to legitimize large-scale looting and seemingly constitutes a de facto license to loot. Thus any near-term measures short of an outright ban, such as efforts to improve the tendering and contracting process while continuing to issue new contracts, would run the risk of further increasing the scope for industrial-scale looting without yielding benefits in terms of government revenue. A temporary ban on new contracts would be straightforward to implement and would at least hinder further expansion of looting.

Focus on improving implementation of existing contracts, with top priority given to ensuring that the government budget gets a share of mining revenues. Several hundred mining contracts are currently in effect, and they should be the focus of attention for the MoMP and other government agencies. The widespread abuse of exploration contracts to engage in commercial extraction with no payments to the government must be curbed. Although publication of mining contracts is a positive step, and many contracts are already available on the MoMP’s website, it will not mean much in the absence of systematic monitoring by the MoMP of contract implementation and required payments to the government.

Monitor export of mineral products at the main border crossing points, where resources that are being looted on an industrial scale clearly are nonlootable (in Snyder’s definition). Customs units of the Ministry of Finance (MoF), though widely considered to be plagued by corruption in the collection of import duties, do at least have some countervailing pressures and incentives on the import side to mobilize more revenue and therefore to engage in at least some degree of monitoring and oversight of imports. On the export side, there are no such countervailing pressures and incentives, not least since export taxes are negligible. Thus practices such as mislabeling of exports (for example, lapis lazuli in container loads listed as agricultural products) go unchecked. Stronger supervision, administrative measures, and possibly also financial incentives should be deployed.

As an emergency measure, impose a levy on mineral exports at border points. The situation has become so dire that drastic measures are called for. However, banning exports entirely has not worked, whether in the case of lapis lazuli or talc. But the government can and should collect significant revenues from ongoing mineral exploitation. The best collection points are the few border crossings where minerals are exported in large truckloads. Any mineral export levy would need to be kept simple, charged on the basis of weight or per truck. Such a levy, collected by Customs and forming part of the revenue stream generated by the Customs department, would also provide some countervailing incentives and pressures for Customs units to better monitor mineral exports. Another option to consider would be a levy on trucks carrying mineral loads at other key transport points, for example, on the main roads going through and immediately around Kabul.

Institute systematic cross-checking between the MoMP, MoF, and MoCI on mineral exports and revenues. As and when monitoring of mineral exports at the main border crossings improves, information on these exports should be cross-checked with MoMP data on extraction and with mining contract provisions relating to the payments that should be made to the government under such contracts. A joint MoMP-MoF team should be formed to ensure that taxes and royalties are paid on any mineral resources extracted and exported on a significant scale. The MoCI also should be involved because that ministry issues export licenses and collects some fees related to exports.

Explore the use of modern technology to monitor extraction activities, especially the transport and export of minerals. Industrial-scale looting involves transport by large trucks traveling on a few main arterial highways and crossing the border at only a handful of crossing points. Thus satellite and other remote monitoring technologies should be considered and tested. In some cases, remote monitoring of extraction activities (or at least the first stage of transport out of the mining area) may also be possible if the resource concerned is concentrated in a relatively small geographic area, as in the case of lapis lazuli.

Over a medium-term time horizon, provided that effective near-term measures are implemented and some progress is achieved in reining in looting and directing more payments to the government, bolder changes and reforms may be possible:

Move toward a political consensus that part of the proceeds of mineral exploitation must go to the government budget. Industrial-scale looting is fundamentally a political problem, requiring political solutions. Afghanistan faces so many other problems that taking this issue to the political level may seem overly ambitious in the current fragile and uncertain political environment. But a consensus-based approach that cuts across different mineral resources, regions, and political groupings is likely to be more manageable politically and could work better than taking on individual resources one at a time, which almost inevitably would risk being perceived as singling out specific groups or geographic areas for punishment.

Train Afghan security agencies, in particular those responsible for law enforcement on major roads and at border crossing points, to identify different mineral commodities and determine whether individuals and companies extracting and transporting them are complying with applicable laws and the terms of mining contracts. Training alone would be far from enough, but it would facilitate progress if combined with the other actions recommended in this report.

Prioritize ascertaining the beneficial ownership of mining companies and making it transparent. The existence of hidden shareholders and beneficiaries appears to be a widespread phenomenon in the extractives sector. Although making progress in identifying and exposing this hidden beneficial ownership will be difficult and will take time, it is clearly a priority in the medium term. Under AEITI, a roadmap for promoting beneficial ownership transparency has been prepared that calls for data collection to start by the beginning of 2018. Although this timetable may be overly ambitious if critical short-term actions are not undertaken soon, it does underline the importance of pursuing this agenda.

Progressively institute international monitoring of Afghan mineral flows outside the country. Many Afghanistan-sourced mineral resources as they are presently being extracted and traded arguably can be considered conflict minerals, so there is an international obligation to avoid validating, let alone stimulating, market demand for them. International monitoring will require international political buy-in and cooperation. A salient example is lapis lazuli, all significant quantities of which originate in Afghanistan: it should be possible to put in place a mechanism to try to ensure that lapis reaching main international markets (most notably China) has been legally exported and that a reasonable level of royalties and taxes has been paid on it to the Afghan government. Other minerals, such as chromite and nephrite, will most likely be more challenging to manage, but the transit and especially the processing of chromite, for example, may be concentrated enough that monitoring can be introduced and tightened over time.

Conclusion

The burgeoning phenomenon of industrial-scale looting of many Afghan mineral resources is extremely harmful to the country—strengthening and further entrenching power holders, corrupting the government and undermining governance, providing some funds to the Taliban and reportedly ISIS, and fueling both local conflicts and the wider insurgency. This dire situation calls for a multipronged and effective response. There is no guarantee that even the drastic measures proposed in this report can be fully implemented, let alone that they will resolve the problem of industrial-scale looting. However, serious actions along these lines are urgently required to hinder further expansion of the looting, begin to contain it, and progressively reduce it over time.

About the Authors

William A Byrd is a senior expert at the United States Institute of Peace (USIP).

Javed Noorani is an independent researcher and a board member of the Afghanistan Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission (MEC).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.