Russian Analytical Digest No 210: Political Mobilization in the Run-Up to the Presidential Elections

17 Nov 2017

By Andrei Semenov, Jan Matti Dollbaum, Levada Center, Jardar Østbø, Oleg Zhuravlev, Svetlana Yerpyleva and Natalia Saveleva for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published by the Center for Security Studies, on 14 November 2017.

How Far Can They Go: Russia’s Systemic Opposition Seeks Its Place

By Andrei Semenov

Abstract

The upcoming 2018 presidential elections in Russia present a familiar challenge for the mainstream opposition: to take part in the Kremlin’s well-organized play as statists or try to push the boundaries of the possible. The latter is strongly linked to the amount of the resources available to opposition players. In this article, I outline the discursive, institutional, and financial resources accumulated by the mainstream opposition (KPRF, LDPR, Just Russia, and Yabloko), and argue that, for now, a full-fledged assault on the regime by these parties is highly improbable: their electorate is shrinking, they rarely control executive or legislative powers on the subnational level, and institutional rules ensure their expulsion from power if they constitute a real threat. Therefore, survival and not expansion is at stake in these elections. However, the opportunities created by the campaign combined with the sizeable number of undecided voters give the systemic opposition a good chance to direct the resources they have towards strengthening their bargaining position vis-a-vis the dominant party.

Presidential Elections: Does Participating Make Sense?

In March 2018, Russian voters will face presidential elections that will decide the fate of the country for the next six years. They are also about to choose from a familiar list of candidates: while Vladimir Putin is “thinking“ about his participation in the race, some contestants have already started the campaign. LDPR frontman Vladimir Zhirinovsky will run for the sixth time—an unmatched record in post-Soviet history. Yabloko nominated its founder Grigory Yavlinsky (he ran in 1996 and 2000; in 2012 he was denied registration), and Just Russia’s Sergei Mironov is looking for confirmation for his third presidential bid at the party convention in December 2017. The Communists (KPRF)— the second-largest faction in the State Duma—appear to be divided on this question, but the odds that Gennady Zyuganov will join the campaign are high: for the Communists, maintaining internal cohesion seems to be a priority over electoral results.

In short, all the candidates from the systemic opposition— the parties that are to varying degrees coopted into the power structures, but are largely excluded from the decision-making process—are politicians from 1990s who have already lost the race to the incumbent several times. Some intrigue remains if Aleksei Navalny eventually will be allowed to run (likely not), or if Kseniya Sobchak—a TV-star and a vocal member of 2011–2012 For Fair Elections! movement—will become a focal point for discontented voters. But even with their names on the ballot, the opposition cannot seriously threaten the incumbent’s dominance. A recent Levada-Center public opinion poll indicates that 48% of respondents (and 60% of likely voters) will cast their vote for Putin, while Zyuganov and Zhirinovsky might expect the support of 2% of the population and the rest of the possible candidates—less than 1%.

With these numbers, the opposition’s participation in the presidential elections appears to be a useless enterprise, so why it is willing to invest in it? The same poll shows that a significant fraction (24% of the respondents, 30% of likely voters) is unsure about their choice, while 18% of respondents do not want to see Putin as president for another term. If these parties (KPRF, LDPR, JR) are regarded as independent political players (which they seldom are), the campaign can serve as a means to widen their support base, send a signal of strength via mobilization of followers, and, in the end, provoke splits within the regime. But even if the systemic opposition’s participation is viewed merely as part of the Kremlin‘s strategy to present voters with ideological alternatives that do not challenge the established power relations, these parties need to attract dissatisfied voters to guarantee a turnout that satisfies the needs of the Kremlin. To achieve these aims, they need to pool their specific types of resources: powerful narratives, appealing to those in doubt; mobilization structures and leadership on the ground capable of generating electoral support; and the allies and financial resources required to maintain the respective parties’ electoral machinery. How well prepared is the systemic opposition to achieve these goals? Let us examine the current state of affairs.

Political Narratives and Policy Positions

On the discursive side, the parliamentary opposition decided to stick with their usual stories. All three parties continuously lament United Russia’s domination and instances of unfair elections but avoid critiques of the president. All three share nationalistic and anti-corruption discourse and target specific government policies, typically economic. Above all, the parliamentary opposition praises the foreign policy achievements of the president and his anti-Western rhetoric. Programmatic statements are vague or veneered in lengthy party documents; consequently, many policy positions are close to each other or identical. For example, the parliamentary opposition in different forms promotes increasing public spending in education and health, enhanced state regulation of the economy, and direct elections of local executives. Even Yavlinsky’s program with its anti-communist flair and claims to restore historical continuity (istoricheskaya preemstsvennost) resembles a soft version of the LDPR’s statements. Among the contenders, Yavlinsky unequivocally regards Crimea as a territory of Ukraine and speaks for the restoration of good relationships with this country. However, apart from this issue, all the mainstream opposition parties present nebulous policy positions and narratives, a feature that will not help the voters find the best fit for their preferences.

Regional Elections

Is there enough institutional basis to convey the messages of the opposition candidates? In other words, how successful has the opposition been in winning political office? Thus far, the tally has been less than impressive. During the 2012–2016 cycle, KPRF members Sergei Levchenko and Vadim Potomosky became governors of Irkutsk and Orel oblast’s respectively. Levchenko won office in 2015 in a highly contested campaign, defeating the incumbent Sergey Eroshenko in the second round, while Potomsky was appointed by the president in 2014 and then elected in a referendum-style manner with 89.2% of the votes. LDPR member Aleksei Ostrovsky assumed the governor’s seat in Smolensk oblast in 2012via appointment and won election in 2015. Following the latest rounds of gubernatorial firings, in October 2017 the president appointed Alexander Burkov from Just Russia to lead Omsk region, while Andrei Klychkov replaced his comrade Potomskii in Orel. In short, only Levchenko win his position via popular vote; the rest climbed the ladder with help from the president. As the president possesses the authority to remove any governor at any time, the regional executives have an excellent reason to behave and limit their ambitions in electoral pursuits. For those candidates without support from above and who decided to run anyway, the municipal filter (the requirement to collect local council members’ signatures to qualify for the race) is a significant obstacle. Some well-known independent politicians in the regions, like Konstantin Okunev in Perm krai or Evgenii Roizman in Sverdlovsk oblast, were unable to register their candidacies precisely because they could not pass the filter.

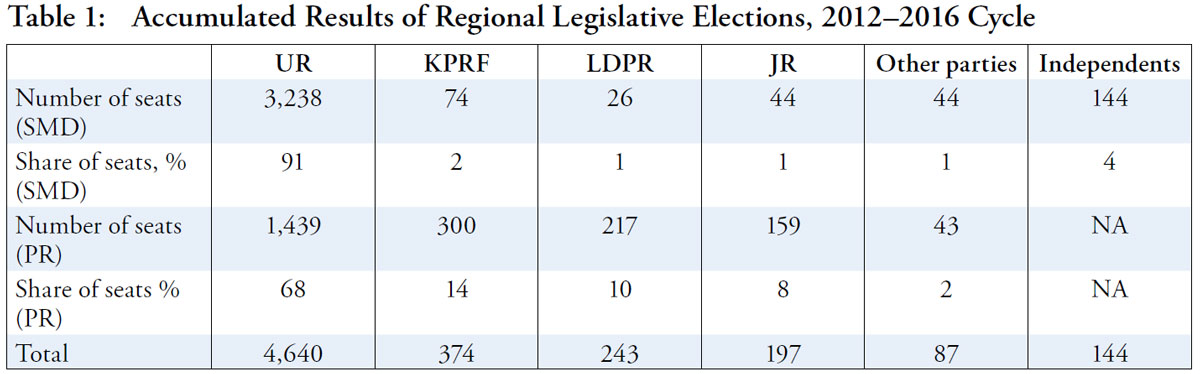

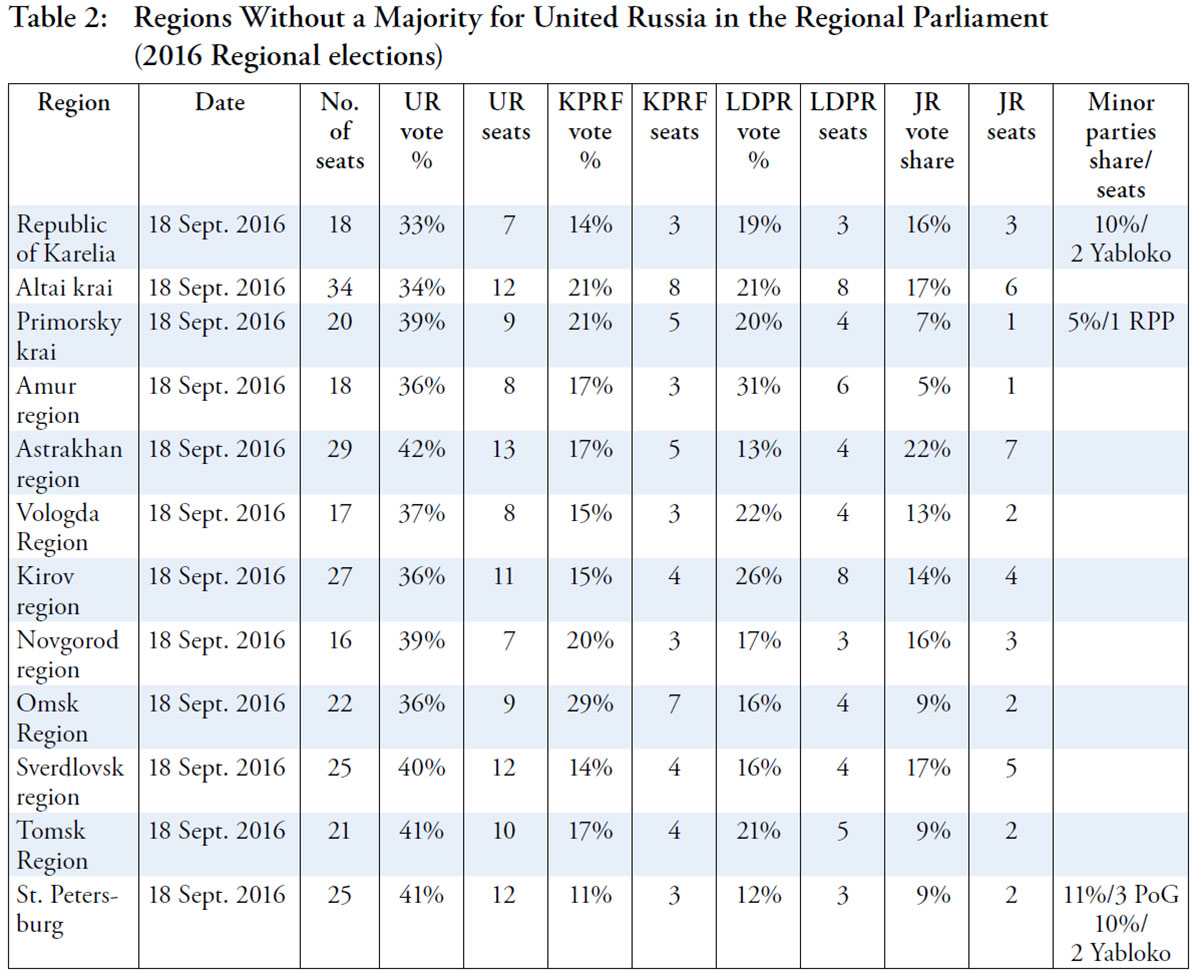

Regional legislative elections also did not bring significant results. Moreover, the mean percentage of votes for United Russia increased from 52.7 percent in the period between 2007 and 2011 to 54 percent in 2012– 2016. The margin of victory also increased by four percentage points (from 34% to 38%). In total, during the 2012–2016 cycle, the opposition parties were able to capture 719 out of 2,158 seats (33,3%) in the regional assemblies via party lists and only 188 out of 3,570 (5%) via single-member districts (Table 1 on p. 5)1. In a handful of regions, United Russia lost its majority status and opposition factions there occupy more than 50% of the seats (Table 2 on p. 5). The Republic of Karelia and Altai krai held the most competitive elections with the effective number of parties exceeding 3. The KPRF has the most substantial presence in Omsk oblast with 29% of the votes in the last elections, LDPR—in Amur region (31%), and Just Russia in Astrakhan (22%). Yabloko did not have significant achievements, yet, it passed the electoral threshold in Karelia, Pskov, and St. Petersburg. Outside the circle of old-school opposition, the Patriots of Russia party came in second in the 2012 elections in North Ossetia with an astonishing 27% of the vote. The party organization was led by ex-United Russia member Arsen Hadzhaev, and its success was largely attributed to his loyal constituents. But in general, the playing field is tilted entirely in favor of the dominant party: Single-member districts (SMDs) ensure UR’s presence in legislatures, while high electoral thresholds and other characteristics of elections shrink the representation of its rivals. Spoilers (recently created parties that closely resemble the established ones in order to split their electorate), administrative pressure, and electoral fraud do the rest of the job to prevent the opposition from obtaining a sizeable presence in power.

Local Elections

Capturing mandates and offices in the regional capitals is an essential aim for the opposition because it usually appeals more to urban voters. The last electoral cycle did not bring much success in this regard either: several opposition leaders took mayoral offices—Yevgeny Urlashov in Yaroslavl (Civic Platform, 2012), Galina Shirshina in Petrozavodsk (Yabloko, 2013), Yevgeny Roizman in Yekaterinburg, (Civic Platform, 2013), and Anatoly Lokot‘ in Novosibirsk (KPRF, 2014). However, only the latter was able to consolidate his power. Urlashov tried to unite the local opposition under the Civic Platform banner and even attempted to run for the governor’s seat in 2013, but was detained, charged with corruption and sentenced to 12.5 years in prison. In Petrozavodsk, after a prolonged conflict with the governor and the city council, Shirshina was ousted from mayorship by the council’s decision. She attempted to challenge this decision in court to no avail. Roizman’s position remained weak because of the shortage in institutional powers; his bid for the governorship in 2017 failed due to the inability to overcome the “municipal filter,” since United Russia members dominate in the local councils. The municipal elections in Moscow in September 2017 seem to break this chain at first glance as Dmitry Gudkov—former JR member and one of the leaders of the For Fair Elections! movement—managed to get 267 of his supporters elected, among them members of Yabloko, which received 176 seats in 51 local councils. But even this achievement cannot provide the opposition candidates for the upcoming Moscow mayoral elections with a sufficient number of signatures. This situation creates a vicious circle for the challengers: without executive powers they cannot control the electoral machine, which is necessary to ensure opposition representation in the councils, which in turn is a prerequisite to have a sufficient number of signatures to run for executive office. All that remains is to bargain with the dominant party to gain its support—a process that is already ongoing.

Funding

This brings us to the last question, namely, powerful allies and financial resources that are necessary to negotiate with United Russia and the regime. Here, despite being primarily excluded from policymaking, major opposition parties were able to raise a considerable amount of funds for the last federal elections. The LDPR garnered 663 million rubles, even outpacing United Russia, Just Russia managed to harvest 432 million, Yabloko—364 million, and the KPRF—176 million rubles. These numbers do not account for the regional and single-member districts funds, and other forms of payments like “chernyi nal” (an unregistered and unsupervised cash flow)2. The parliamentary opposition is not devoid of wealthy individual sponsors within their ranks, either: according to a RBC report, the mean annual income of JR’s members of parliament is 22.5 million rubles, LDPR—17.6, and KPRF—13.4 million rubles. The reference level set by UR MPs is 25.3 million. On the sub-national level, all the mainstream opposition parties try hard to attract moneyed sponsors in return for a place on the party list. Again, United Russia remains the most trusted recipient of investment; however, the numbers described above is indicative of the readiness of various sponsors to support the opposition financially.

Taking Stock of the Resources

The systemic opposition at this stage apparently cannot pose a significant threat to Vladimir Putin and United Russia. Each of the parties on this flank sticks to their core constituency preferences, hence, the familiar faces and no changes in narratives. Each party has a limited presence in the regions which is sufficient to help their candidates run the race, but not sufficient to mount a full-fledged assault. Fundraising seems to be the least important issue: in addition to sponsors’ money, all parliamentary opposition parties are eligible for state funding.3

Navalny’s campaign contrasts starkly across all dimensions with that of the mainstream opposition as it is limited in its material base yet anchored in a powerful narrative that resonates with certain social demands. At least some of the mainstream opposition leaders seem to acknowledge the lackluster character of their campaigns—but are they willing to trade their privileged status and ambitions for an alliance with energetic yet not widely popular politicians? However obvious the answer to this question might be, there are still dissatisfied voters out there who can turn the campaign in one direction or another, and the systemic opposition should rather be aware of that.

Notes

1 This count does not include elections in Sevastopol and Crimea Republic. 144 independent candidates won SMD seats during the same period.

2 Edinoi Rossii golosa oboshlis v 20 raz deshevle, chem Yabloku [United Russia spent 20 times less per vote than Yabloko] <https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/articles/2016/09/27/658595-edinoi-rossii-deshevle>

3 In order to be eligible for state funding, the party list should receive more than 3% of the votes in federal elections. Yabloko used to meet this threshold from 2011 to 2016 but fell below it after the last elections.

About the Author

Andrei Semenov is the director of the Centre for Comparative History and Politics, Perm State University.

When Life Gives You Lemons: Alexei Navalny’s Electoral Campaign

By Jan Matti Dollbaum

Abstract

Since the opposition politician and anti-corruption activist Alexey Navalny announced his plan to become president in 2018, his team has built one of the most extensive political campaigns in post-Soviet Russia. In the context of electoral authoritarianism, the competition takes place on a highly uneven playing field. Although it remains unlikely that he will be allowed to run in the election, the campaign’s central strategy—to turn obstacles into advantages—confronts Russia’s political leadership with its first real challenge in years.

Navalny: I’m Running

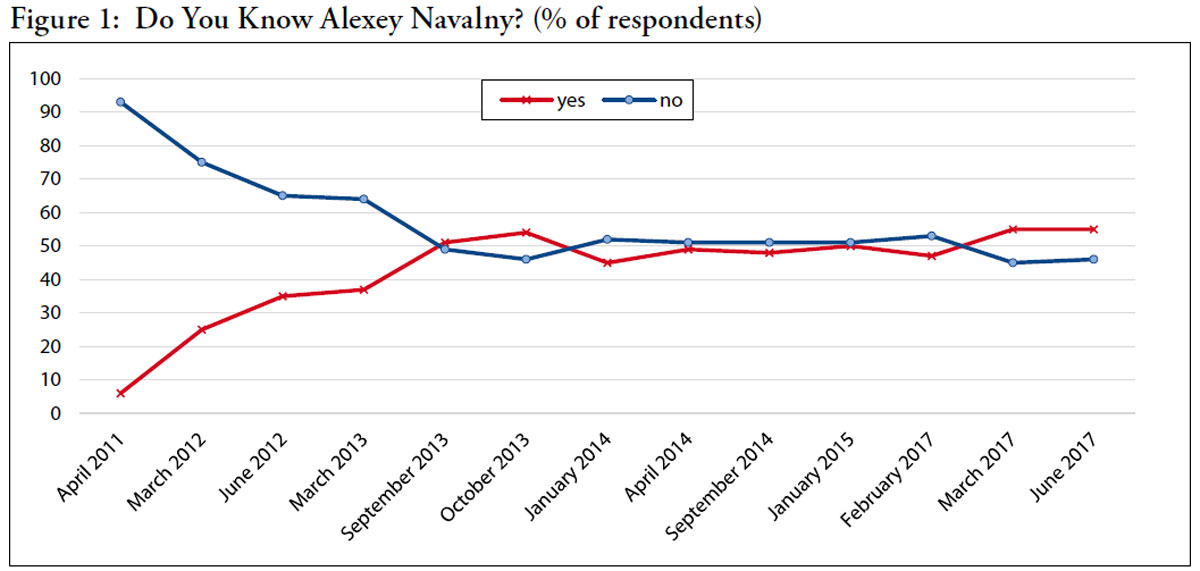

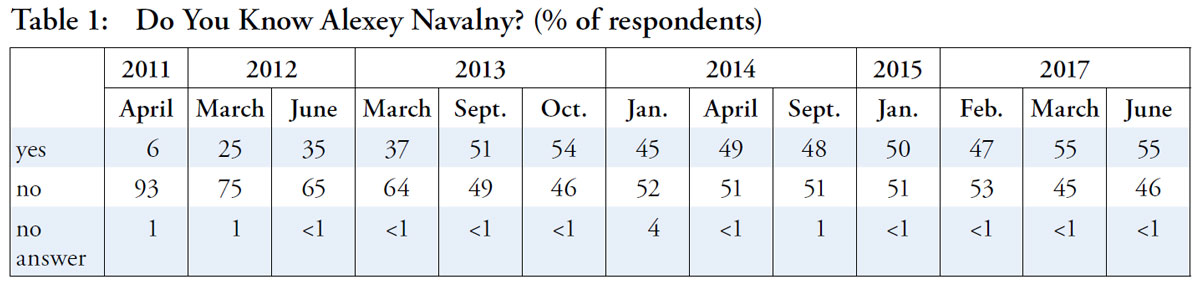

In December 2016, Navalny declared his intention to take part in the 2018 presidential elections. With this decision, he substantiated his claim for leadership within the Russian non-systemic opposition. Navalny had begun his political career as an activist for Yabloko’s Moscow branch, quickly climbing the party hierarchy. Yet in 2007, the party expelled him, pointing to his nationalist statements (Navalny himself asserts the real reason was his criticism of Yabloko leader Grigori Yavlinsky). After that, he founded the organization “The People” (NAROD), which called itself “democratic nationalist” and claimed to advance the interests of ethnic Russians, yet rhetorically distanced itself from radical nationalists and cooperated with democratic opposition forces. And although he removed all nationalist rhetoric from his current campaign, some liberals and leftists still uneasily remember Navalny’s appearances at the “Russian Marches” until 2011 and his nationalist positions in his blog (see Moen-Larsen 2014). In the elections to the Coordination Council of the Opposition, a short-lived attempt to institutionalize the heterogeneous For Fair Elections movement in 2012, Navalny gained the most votes of all 209 candidates. His effective campaign in the 2013 mayoral elections in Moscow, where he received 27% and almost forced the Kremlin-backed candidate Sergey Sobyanin into a run-off, then finally established him as the most serious challenger to the current political system.

In parallel to his political career, Navalny became the country’s best-known anti-corruption activist. As a minor shareholder of several large energy companies, he has access to some of the firms’ internal documents. These form the basis of large-scale investigations into the entanglements of big business, state corporations and the administrative elite. Additionally, with a team of capable lawyers and IT-savvy colleagues, he built crowd-based mechanisms for corruption detection and automatic complaint filing. The results of this activity are brought to the public in stylish, often sarcastic video clips that hit a nerve on social media. His most successful piece, a 45-minute film on the alleged corruption of Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, has been viewed over 25 million times. And indeed, absent neutral (let alone positive) coverage on state-controlled television, social media is the single most important way for Navalny to engage with the electorate.

Khozhdenie v narod—The Regional Campaign

Equally central for his efforts to increase his popularity on the ground is the creation of a regional network of supporters. The electoral law requires presidential candidates without the backing of a party to assemble 300,000 signatures from at least 40 regions, with no more than 7,500 coming from each region. Furthermore, these signatures can only be collected after the elections have officially been called, which cannot happen earlier than 100 days before election day. If, as planned, elections will take place on 18 March 2018 (the date of the annexation of Crimea in 2014), Navalny can start collecting signatures in December and must end in late January, as the signatures have to be handed in 45 days before election day. It is obvious that in so short a time, no powerful campaign can be wielded, especially given the extended holidays around New Year. This design of electoral rules is part of a larger strategy common to electoral authoritarian regimes: while elections are the most important channels to fill political offices, the rules of the competition are skewed in favor of the established set of actors—in this case the candidates of United Russia and the systemic opposition.

The campaign openly acknowledges this structural disadvantage, and faces it head on: their strategy is to build a network of supporters before the signatures can officially be gathered. Thus, since February 2017, the team has been opening offices in big cities across the country, with the aim of being represented on the ground in 77 (of the officially 85) regions. In each regional “team,” the campaign pays for three or four staff members. This paid core recruits volunteers for street and online agitation and collects data from citizens willing to be called upon when the signature gathering starts. At the time of writing, the campaign claims to have collected such promises from over 630,000 people. They strive for one million—not only for the symbolic number, but also to be on the safe side: Electoral commissions are notorious for denying candidates registration on the grounds of allegedly flawed signatures.

Turning Obstacles into Opportunities

With his regional campaign, Navalny tries to make the most out of the existing rules of the game. While the regulations are designed to keep unwelcome contenders off the ballot, they also motivate upstart opposition figures to intensively engage with the electorate: Volunteers must be found for the work on the ground, citizens must be persuaded to give their personal data to the campaign. Moreover, being able to show broad regional support demonstrates closeness to the people. While Navalny’s campaign represents a liberal, digital and entrepreneurial Russia, it tries to avoid being perceived as elitist—a stigma that still undermines support for liberal politics in Russia. Hence the recurrent emphasis on crowd funding as the campaign’s only financial resource,1 and hence the strategic importance of a supporter base outside the capitals of Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Yet, no matter how much effort is invested, the authorities have the final say on whether Navalny will run. In February, he was convicted of fraud in the “Kirovles” case and issued a suspended five-year prison term. As the alleged crime was ruled to be “severe,” the electoral law precludes him from standing for elections. The court of appeal upheld the ruling in May. Consequently, Navalny can only take part in the presidential elections if the High Court annuls the ruling (possibly as a consequence of a decision by the European Court of Human Rights, as happened before), or if the Constitutional Court, to which Navalny announced he will appeal, rules the Kirovles verdict unconstitutional. Theoretical chances exist since the constitution does not explicitly discuss the restriction of an individual’s right to run for public office following a suspended sentence.

Nevertheless, neither is likely to happen. But again, the campaign’s strategy is to turn obstacles into advantages. First, pretending to conduct a normal electoral campaign in highly unfavorable circumstances bolsters one of Navalny’s main messages: a demand for normality. Navalny thus tries to use the environment in which he is campaigning as a framing resource—the state as a dreadful and incompetent Leviathan is set against the vision of a modern, well-functioning set of institutions that his campaign embodies.

Second, the campaign seeks to use every instance of repression for an immediate counter-attack. Any court proceeding conducted against Navalny becomes a stage for political speeches: In his concluding remarks in the Kirovles case, publicized later, Navalny directly addressed the judges, the procurator and even the guard in the court room, arguing that they could immensely improve their living conditions if they would deny their support to a regime that benefits only a few thousand members of the elite. Furthermore, each of the many harassments against the regional campaign offices is posted and commented on via social media. Depending on the severity of the attacks, these instances are either used to lament the regime’s indecency—or to ridicule it.

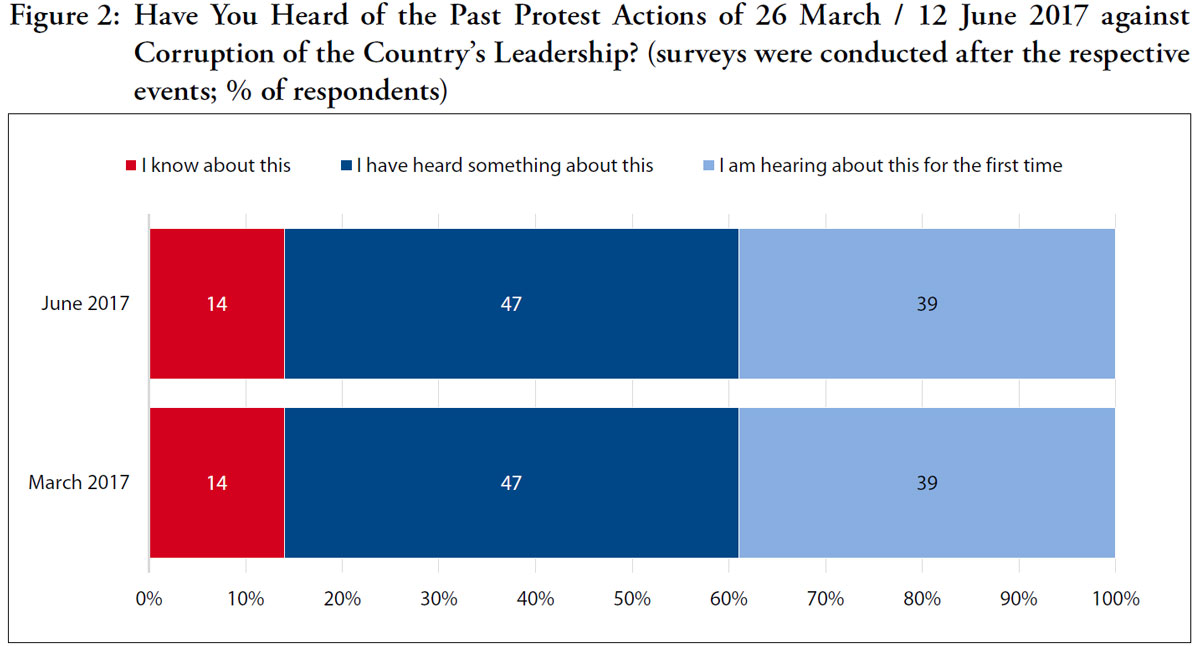

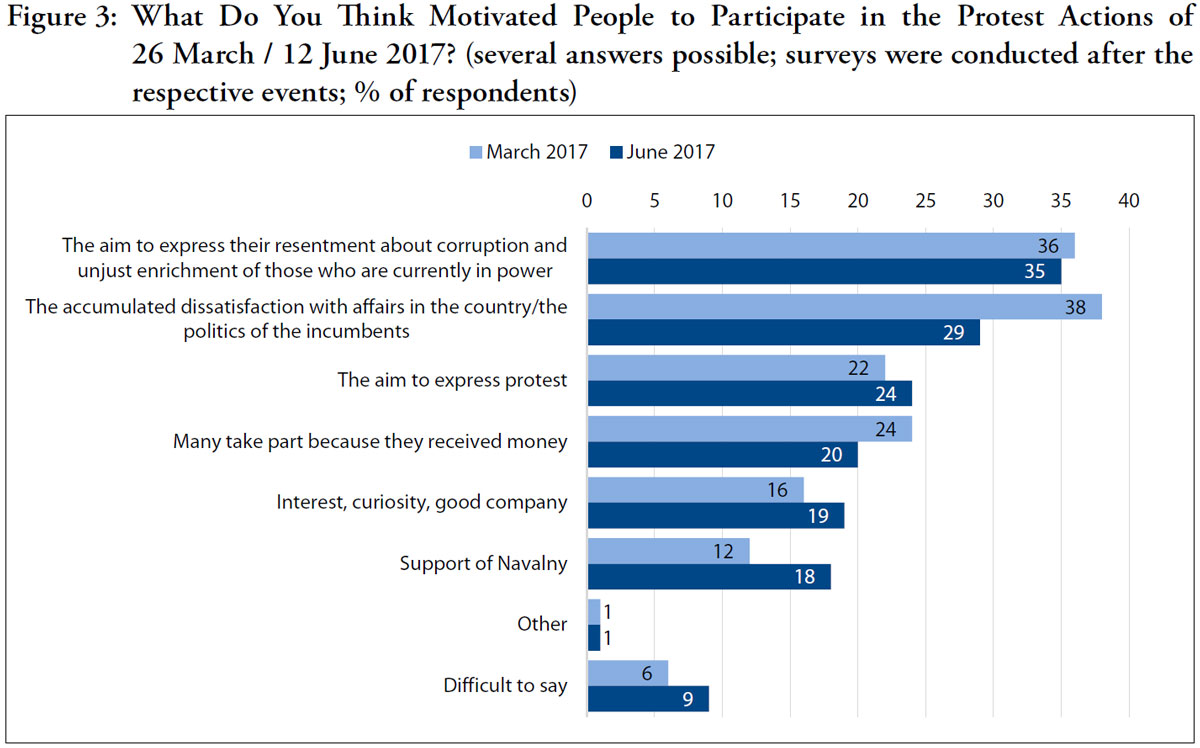

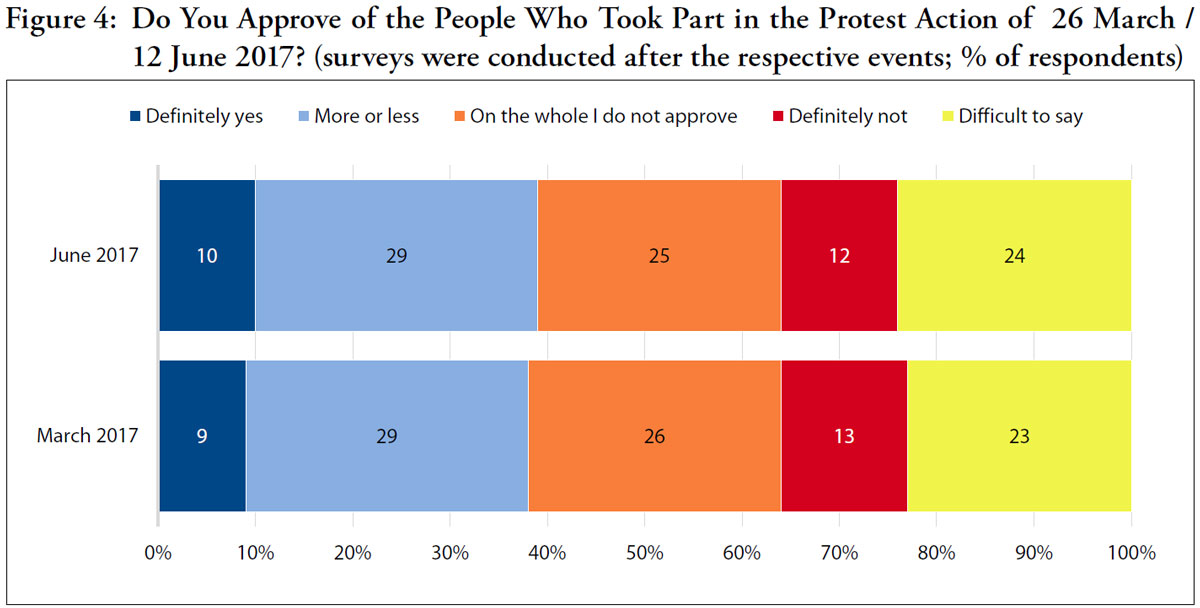

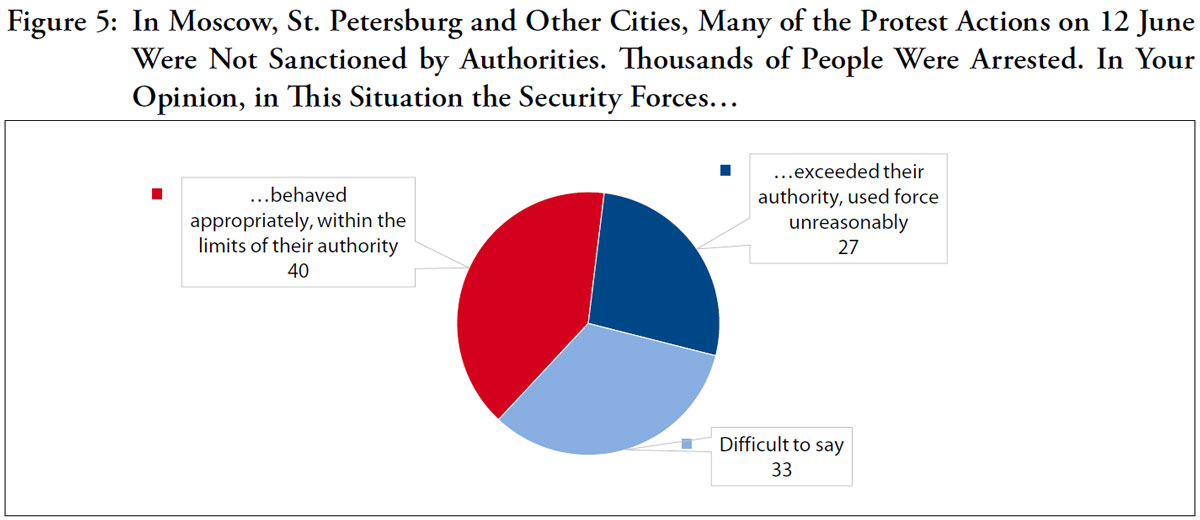

Protest Politics

Yet, the campaign does not just try to capitalize on arbitrary actions by the regime: Through well-placed provocations it forces the authorities to react, which often elicits clumsy and not always lawful responses by the lower bureaucracy. This strategy is most articulate in street protests. On 26 March and 12 June 2017, the campaign organized the largest demonstrations since the For Fair Elections protests in 2011/12. Mobilizing on an anti-corruption message, the campaign brought tens of thousands to the streets—in a hundred cities across the country. The response was fierce: on 12 June, over 1,000 people were detained, more than 700 of them in Moscow, where Navalny changed plans in the last minute and called on his supporters to gather at a place that had not been agreed upon with the authorities.

The second, currently ongoing wave of large public events is framed, with ostentatious naivete, as a tour of meetings between the presidential candidate Navalny and his supporters. The campaigners plan to conduct such meetings—read: mass demonstrations—in 50 cities before December. Yet, after the first two weekends of meetings (including a rally in Yekaterinburg with several thousand participants), these plans were stalled, when local authorities started to decline the campaign’s requests for conducting the events. According to the law on public gatherings, demonstrations must be registered. Yet the law only grants local authorities the right to suggest an alternative time of day or another spot in the city. It does not provide for outright rejections. Referring to this law, the campaign in turn announced that it would treat such rejections as non-answers, which are judicially tantamount to permissions. On 29 September, shortly after this announcement, Navalny and his chief of staff Leonid Volkov were arrested and charged with calling for participation in non-sanctioned protest actions. They spent the next 20 days in jail. Upon release, when the series of meetings was to be continued and local authorities declined virtually all requests, the campaign changed tactics: in addition to sending out hundreds of further requests, they apply to private owners of urban space, such as central parking lots or large indoor areas, since in such cases no consultation with authorities is needed.

Programmatic and Organizational Trade-Offs

Behind this strategy, which always claims to have the law on its side (indeed several recent court cases against local authorities have been won), stands Leonid Volkov, a former businessman and political activist from Yekaterinburg. Volkov enjoys high respect among the regional activists of the campaign for his evident organizational talent. Yet, the impressive efficiency of the campaign is made possible through strict hierarchy and division of labor. Regional offices have to meet hard targets of volunteer agitation and signature gathering, which are regularly checked in great detail by the Moscow headquarters. In a few cases, local coordinators have been fired due to inefficient work on the ground. Decisions by the center cannot be overruled. This strictness raises some eyebrows among the local staff, but it does not meet resistance. However, those outside critics who point to an authoritarian leadership style and compare the campaign to a corporate machine rather than a movement certainly have a point.

Efficiency thus has a price, and so does Navalny’s effort to appeal to leftists, liberals and an unpolitical audience alike. His program (to which supporters cannot contribute from the bottom up) is vague, weak on details, and has been attacked from many sides. Leftists see the resurgence of market radicalism in his plan to abolish taxes for small businesses, while liberals hesitate to embrace his promises of increased social spending and a monthly minimum wage of 25,000 rubles. Yet, Navalny’s claim for “normality” might indeed be a sensible common denominator. A “normal” government that invests in education and infrastructure, a “normal” state with functioning, non-corrupt institutions that respect political freedoms and civic rights, and a “normal” market economy, where profits are not shipped to offshore tax havens—this may not sound like an exciting program. But it is this centrism, plus his persistent rhetorical attacks on oligarchs, that makes it difficult to dismiss Navalny as yet another of the much-disliked reformers of the 1990s. His statements on foreign policy are an equally carefully designed walk on the tightrope: he condemns Russia’s intervention in the Donbass, but only on strategic, not moral grounds, and he does not fully reject the annexation of Crimea. Instead, he demands a “normal” referendum, i.e. one that is conducted with respect to democratic standards.

The economic eclecticism and his charismatic, authoritative appearance make Navalny a candidate that is not entirely unlike Putin. This is not without reason in a situation where the current president is probably backed by a majority of the populace. Existing programmatic differences, on the other hand, are stressed aggressively: plans to conduct a major campaign against corrupt bureaucrats and oligarchs, to make the judiciary politically independent, and to liberalize the political competition are recurrent elements in his speeches and videos. Bringing home these points is important, but equally important is to undermine the population’s trust in Putin as a person—as his power rests upon this trust. Therefore, the relentless series of videos exposing corruption in Putin’s inner circle keep sending the same message: if Putin tolerates these excesses, he is not worth the people’s support—no matter what his policies are.

Conclusion

Alexey Navalny‘s campaign tries to make the best out of the regulations and practices of electoral authoritarianism. It uses every opportunity that the state must give to uphold at least a democratic facade—and provokes the regime into crossing the boundary. Repression, then, is immediately turned into a source of negative framing. The campaign shows the corruption and repressiveness of the regime on every smartphone screen, and mobilizes thousands of people who demand a choice at the ballot box. Evidently, exposing Russia’s hybrid authoritarian framework, where authorities interpret laws to suit the needs of those in power, is a central part of the campaign’s strategy. In a paradoxical twist, however, the campaign also tries to use this hybridity for itself: Should the Kremlin’s campaign managers come to the conclusion that Navalny’s participation in the elections would be in their favor—since it would lend the elections at least some legitimacy—then a way will be found to have him on the ballot. The campaign’s argument is simple: if the presidential elections are to be more than a farce, Navalny must be allowed to run. The campaign’s goal is to pressure the authorities into acknowledging this—even if that means one more act of interference from above.

Notes

1 The campaign publicizes the sums of collected money and the way it is used, but remains silent on the sources of donations. From personal conversations with people close to the campaign, however, the author knows that financial support not only takes the form of small donations by private citizens but also comes from owners of small and medium enterprises.

Further Reading

• The basic points of Navalny’s program (in Russian): <https://2018.navalny.com/platform/>

• The finances of the campaign as presented by chief of staff Leonid Volkov (in Russian): <https://www.leonidvolkov.ru/p/237/>

• A call for solidarity with Navalny from a left-wing perspective (in English): Budraitskis/Matveev/Guillory: Not justan Artifact <https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/08/russa-alexey-navalny-anticorruption-movement-left>

• Criticism from liberal economist Andrey Movchan (in Russian): <https://www.znak.com/2017-07-13/ekonomist_andrey_movchan_ob_opasnosti_avtoritarizma_v_postputinskoy_rossii>

• Oleg Kashin on the interdependence of Putin and Navalny (in English): <https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/03/opinion/russia-putin-aleksei-navalny.html>

• Moen-Larsen, Natalia (2014): “Normal nationalism”: Alexei Navalny, LiveJournal and “the Other”. In: East European Politics, 30(4), 548–567.

About the Author

Jan Matti Dollbaum is a PhD candidate at the Research Centre for East European Studies at the University of Bremen.

Results of Surveys on Alexey Navalny Conducted by Levada Center

Demonstrations Against Demonstrations

By Jardar Østbø

Abstract

This article shows how, in the midst of the patriotic fervour following the Crimea annexation, the Russian regime used mass demonstrations to pacify the population. Rather than mobilizing people to actively participate in pro-regime, anti-opposition rallies, Kremlin spin doctors used social media to spread moods of sadness and fear in order to discourage all popular mobilization, even in favour of the regime.

Background: Pro-Regime Counter-Demonstrations

For authoritarian regimes, which rely on the population’s perception of the regime’s invincibility and the lack of political alternatives, even relatively small opposition-minded demonstrations represent a potential danger. To deal with this, the Russian regime has, along with other repressive and manipulative measures, staged parallel counter-demonstrations of various sorts. After the Orange Revolution in Ukraine in 2004–5, and the mass protests against the monetization of social benefits in Russia, the Presidential Administration set up “patriotic” youth activist organizations such as Nashi (Our people), which mimicked the Orange revolutionaries’ mass gatherings and absurdist performances. When this strategy proved ineffective in preventing the new wave of opposition mass demonstrations from late 2011, the regime used administrative pressure and incentives to make employers and educational institutions send people to mass gatherings that focused not primarily on supporting the regime, but on specific problems such as the “Orange menace.” Since 2014, the strategy of administrative pressure (“surrogate mobilization”) has remained, but the demonstrations have changed.

The Regime’s “Mobilization Dilemma”

The Crimea annexation brought patriotic euphoria and sky-high ratings for Putin. Nevertheless, the liberal opposition mobilized for two mass demonstrations, namely the “Peace March” in September 2014 and what was supposed to be an “Anti-Crisis March” on 1 March 2015. These demanded a response from the regime, but that was easier said than done. In general, even pro-regime mobilization may be dangerous for authoritarian regimes, as they prefer a passive population in order not to jeopardize the balance of the limited pluralism. A mobilized, active population can get out of hand, the agenda can change, new figures may emerge, and radical, but originally pro-regime groups may feel that the regime does not go far enough. Coincidence, provocation or even incompetence, for instance in crowd management, may have catastrophic consequences.

While continuing to ride the post-Crimea wave of nationalism might be a tempting option, the regime was (and is) not in a position to fulfill the hopes of many Russian nationalists, such as annexing the Donbass (too expensive and politically complicated) or articulating stronger Russian ethnic nationalism (which could alienate the large ethnic minority population). A certain nationalist sentiment in the “silent public” is good for the Kremlin—ungovernable nationalist activists on the streets are not.

An analysis of the context, the nominal organizers and, above all, the social media promotion of the two major counter-demonstrations within a year after the Crimea annexation strongly suggests that the regime spin doctors used these occasions to convey a tacit message of de-mobilization. Instead of whipping up action-oriented anger to mobilize a maximum amount of activists, they used the most important platforms (Twitter and VKontakte) to spread the dispiriting and thus pacifying emotions of sadness and fear.

Context of the Public Mourning: Countering a Peace Demonstration

On 27 September 2014, an event called “Public Mourning to commemorate the innocent victims of murder in Donetsk” was staged on Moscow’s Poklonnaia Gora, in front of the monument to the memory of the victims of the Holocaust. According to official sources, as many as 17,000 people participated. The event was announced shortly after the liberal opposition’s surprisingly well- attended Peace March, which in Moscow alone gained a following of at least 26,000 people protesting the regime’s action in Ukraine. The official organizers of the counter-demonstration were two Kremlin-linked but nominally independent “family values organizations.” The pretext was the finding of three unmarked graves on the outskirts of Donetsk, in areas until recently under the control of pro-Kyiv forces. While the OSCE at the time only confirmed finding a total of four bodies, Russian officials and state media were quick to describe them as “mass graves” and evidence of genocide. In contrast to these fierce statements, the Public Mourning as such was in advance announced as calm, dignified, apolitical and consensual. Although all political parties represented in the State Duma were to attend, there were no party slogans. The apolitical message was emphasized by the fact that the official sponsors were organizations focusing on “soft values” (as opposed to “hard politics”), both led by women. In addition, pro-government newspapers attributed the liberal opposition’s boycott to its “obsession” with the political and their insensitivity to people’s feelings.

Mood of the Public Mourning: Sadness

The Peace March was difficult to counter rhetorically without inadvertently compromising the Kremlin’s consistent denial of military involvement in the Donbass or (if they would focus on the image of the enemy) risk creating popular anger and a demand for large-scale Russian intervention. The solution was to use social media to work up a mood of sadness while minimizing the potentially mobilizing moods of blame and anger.

Pro-regime social media profiles who elsewhere would use strong language or even hate speech against the regime’s opponents, now resorted to posting photos of sad-looking people getting ready for the event. A recurring image was a photo of a multitude of slender candles of the type traditionally used to commemorate and honour the deceased in Orthodox churches, accompanied by basic information about the time and place of the event. Here, the perpetrators are left out, with the focus solely on the victims. There are no exclamation points, and the darkness surrounding the candles reinforces the impression of grief. This sense of quiet and dignity stands in stark contrast to the mentioned recent instances of regime-friendly media’s claims of genocide—but it makes perfect sense as an expression of de-mobilizing, “managed” sadness.

This mood is even more evident on the event’s official VKontakte page, which appears to be strictly edited, with commentaries following the official narrative of the war in Eastern Ukraine and of the Public Mourning. There is little sense of anger at the perpetrators, but all the more sadness, and even resignation and hopelessness. Also notable is the facelessness of the victims. Tellingly, the second main photo on the VKontakte page features a weeping girl or young woman, her hand covering her face.

If the regime’s goal had been to trigger a mass demonstration with a genuine following, it would have been expedient to point the anger directly at the alleged perpetrators and show photos of the deceased when they were still alive. Instead, the focus is on human tragedy in general, and the allocation of blame is very diffuse, offering only an unclear image of nefarious, evil forces. When exposed to such imagery, people are actually less likely to attend the demonstration that it would appear to be mobilizing for. And those who decide to attend are less likely to behave in unpredictable ways. In this sense, the “campaign” serves a de-mobilizing function.

Context of the Maidan Anniversary: Against the “Anti-Crisis March”

The next major opposition demonstration was to be arranged on 1 March 2015, as an “Anti-Crisis March of Spring,” signaling that the opposition was to focus increasingly on potentially much more resonant social issues instead of democracy, accountability and peace (the event was widely advertised but then completely reframed as Boris Nemtsov, one leading activist, was murdered two days earlier). With the dire economic prospects at the time, the opposition’s reorientation was bad news for the regime, as its social contract with its core supporters could be in danger.

The counter-demonstration was arranged one week in advance and framed as a one-year anniversary of the culmination of the Euromaidan uprising in Kyiv. Similarly to the Public Mourning, the Maidan Anniversary was advertised as apolitical, but while the former conveyed a sense of (hegemonic) femininity with motherhood, compassion and care, the latter communicated (hegemonic) masculinity, with patriotism, physical strength, and even the cult of violence. The main slogan, repeated from the stage between the acts, was “In Russia there will be no Maidan.” Its organizer, the newly formed Antimaidan Movement, a “patriotic” umbrella organization, featured intimidating board members, such as a motorcycle gang leader and a martial arts champion. The leader, a United Russia State Duma deputy, immediately struck an aggressive posture by threatening opposition activists with violence. Three hundred of his goons followed up on the same day by physically attacking a small, unsanctioned demonstration supporting opposition leader Aleksei Navalny.

Mood of the Antimaidan Anniversary: Fear

The social media campaign of the Maidan Anniversary was directed towards fostering the dispiriting moods of insecurity, resignation, and, above all, fear. The posts were awash with references to chaos and destruction, playing on the Russians’ traumatic memories of the upheaval of the 1990s. In general, fear of “the other” may fuel mobilization, but here, the other was not really identified. What strikes the observer is that instead of authentic photos from the Euromaidan, the public is presented with stylized drawings with little or no reference to concrete figures or events. There is no clear image of the enemy to blame other than an unidentifiable, threatening evil force. Both victims (of the Euromaidan uprising) and enemies are strikingly faceless. A telling example is one picture that appeared several times on VKontakte and Twitter: with flames and smoke in the background, two policemen in anti-riot gear are defending themselves against a numerically superior crowd throwing Molotov cocktails at them. The protesters are portrayed as perpetrators, not victims of violence. But more importantly: they are barely identifiable as human beings—faceless, unclear, black figures in a blurred and colourless drawing which gives a nightmare- like impression. Instead of focusing on the details of human suffering, or the fight between the “evil” protesters and the “good” police, the picture concentrates on the far less clear threat of general destruction—almost like a force of nature. What inspires fear is the situation, the nightmare spectre of chaos.

Fire, as an uncontrollable, destructive force, is a recurring theme on the official poster and in videos posted. Highly present in Russian historical memory (most recently by the 2010 wild fires claiming hundreds of lives), the devastating image of fire is also associated with the Euromaidan (protesters burning tires, and later, a fire in Odesa causing the death of dozens of pro-Kremlin demonstrators). Apart from spreading fear in the general public, the fire images might also intimidate the opposition-minded, reminding them that they are considered a dangerous contagion to be fought with all necessary means.

Hence, Antimaidan’s VKontakte posts and Twitter posts by prominent pro-regime tweeters, on the surface promoting mobilization for the demonstration, are much more logically interpreted as parts of a strategy to prevent mobilization in general. Not suited for generating action-oriented anger, this communication is conducive to engendering fear and insecurity, dispiriting emotions with no direct object.

Conclusions

The social media promotions of the Public Mourning and the Maidan Anniversary, as well as the events themselves, were both de-mobilizing in character. But whereas the former at least had a component of compassion, the latter was much more threatening, conveying the looming danger of violence and destruction—not in a foreign country, but here and now. Whether intended by the organizers or not: The promotion of these two pro-regime counter-demonstrations, especially the Maidan Anniversary, was useful not only from a tactical perspective (limiting attendance), but also on a more strategic level. The emphasis on human tragedy, diffuse allocation of blame, and the unclear, but strong threat of being destroyed by an unfathomable enemy, are geared towards reinforcing feelings in the populace of vulnerability and anxiety about the future, the implied message being that the only alternative to the Putinite regime would be chaos and destruction. Such an atmosphere is, of course, highly conducive to making the people rally around their authoritarian leader, not in a mood of patriotic agitation, but passively accepting the sad state of affairs.

About the Author

Jardar Østbø is a freelance analyst and translator, formerly (2014–17) a postdoctoral research fellow with the University of Oslo’s NEPORUS project, funded by the Norwegian Research Council.

Nationwide Protest and Local Action: How Anti-Putin Rallies Politicized Russian Urban Activism

By Oleg Zhuravlev, Svetlana Yerpyleva and Natalia Saveleva

Abstract

This article analyzes a phenomenon new to Russia: the politicized local activism that emerged in the wake of the Bolotnaya Square protests. Local activism is fundamentally ambivalent in terms of politics. On the one hand, it is fundamentally apolitical (see Gladarev, 2011, Eliasoph, 1996), since it permits people to be content with small deeds while ignoring the large-scale political processes on which people’s lives depend. On the other hand, it functions as a hidden channel for politicizing the apolitical (Bennett et al., 2013). We argue that apoliticism is a specific culture, meaning a set of habitual ways of understanding the immediate world and acting in it. Here, we present our own approach to defining and analyzing apoliticism and politicization.

Defining Apoliticism in Russia

Our main argument is that the anti-Putin protests For Fair Elections politicized local activism in Russia. Urban activism has been a widespread and popular form of contentious politics in Russia as well as in many other post-communist countries. On the one hand, local activism represented protest politics in an apolitical society. On the other hand, it itself was a manifestation of “avoiding politics” (Eliasoph, 1998) since it distanced itself from both conventional and opposition politics focusing instead on “concrete problems” and “real deeds”. That is why post-protest local activism is an important example of the politicization of society in general. But what is apoliticism?

We argue that apoliticism should not be deemed a tautological umbrella term, denoting popular passivity, but a set of cultural and practical mechanisms that generally supports non-involvement in public politics, but might also encourage the emergence of certain types of collective action. We define apoliticism in Russia in terms of three basic elements. The first is a culture that opposes apoliticism, supposedly part of a normal life, to politics. In other words, the societal majority buys into the notion that politics is associated with violence, empty rhetoric, deceit, and corruption. It is something amoral, while private life, associated with honesty, sincerity, success, and dignity, is something good. Second, apoliticism represents the primacy of the private or, rather, familiar realm in people’s daily lives and careers. Whereas the culture of apoliticism consists of collectively shared and emotionally charged meanings, the primacy of the familiar realm means that a particular knowhow is widespread in society. The dominance of private or, rather, familiar know-how in Russia has generated a public realm that is unfamiliar and underdeveloped, and sometimes even “frightening” (see, e.g., Prozorov, 2008). Third, apoliticism is based on certain regimes of visibility, i.e., on means of telling truth from falsehood, the authentic from the inauthentic. Thus, apoliticism in Russia is a stigmatization of politics, the immersion of daily life in private experience, and the authenticity of facts confirmed by personal observation in contrast to ideological mumbo-jumbo. These elements have the force of an imperative, of an obligation. In other words, society says to its members: do not get mixed up in politics, which is dirty; do not step beyond the realm of the familiar; do not trust the ideologically freighted speeches you hear on TV. These selfsame elements of depoliticization in Russia have not only defined political apathy but have also triggered specific kinds of collective action.

A vivid example of how apoliticism can both restrict and inspire collective action is local activism, both in Russia and other countries. We will present the case of activism in the wake of Bolotnaya Square, i.e., inspired by a huge protest, activism that is a pragmatic example of what happens when local collective action is politicized. In other words, by analyzing the new species of local activism, which has become part of the protest and opposition movements, we shall present a microsociological model of social change. We shall see that the fusion of the Bolotnaya Square movement and local activism has spurred the appearance of new, sustainable shapes of collective action, which in turn have facilitated a transformation of political culture in Russia.

Theoretical Approach

In our analysis of the familiar and public realms, we draw on the approach of Laurent Thévenot who has labeled three “grammars of commonality,” which “help to differentiate ways of voicing concerns and differing” (Thévenot, 2014: 9), rather than classic republican theories of the public and private spheres. When we speak of the culture of apoliticism, we follow Jeffrey Alexander in assuming that it is built from society’s prevalent cultural structures, i.e., binary codes, charged with collective emotions, that convey positive meanings to one pole of semantic oppositions, while imparting negative meanings to the other pole (Alexander, 2003: 152). We will show, however, that the transformation of political culture has occurred due to changes in the communicative and practical use of cultural codes. Hence, we will be relying on the approach to culture introduced by Thévenot and Nina Eliasoph, who in their research redefined cultural sociology showing how people differentiate cultural meanings in different ways, depending on the specific communicative and pragmatic circumstances (Eliasoph and Lichterman, 2003; Lamont and Thévenot, 2000). We analyze the regime of visibility in terms of the critical reality test, consistent methods or manners of reinforcing one’s own rightness with words and things (Boltanski and Thévenot, 2006). Finally we uncover the mechanism that put together the experience of Bolotnaya Square and the practices and modes of apolitical local activism using political event theory (William Sewell, 1996; McAdam and Sewell, 2001; Della Porta, 2008).

Methodology and Data Collection

Our article is based on three types of empirical data: interviews with rank-and-file Bolotnaya Square protesters (159 interviews); interviews with focus groups, comprised of members of post-Bolotnaya Square local groups (45 interviews); and, finally, participant observations of the work done by local activists. All interviews, focus-groups and observations were collected between 2012 and 2016.

From Familiar to the Public and Vice Versa

The “Bolotnaya” movement of 2011–2012 was an example of “eventful protests” (Sewell, 1996; della Porta, 2008). It was the first mass political protest since 1993. Hundreds of thousands took part in the rallies against electoral fraud. Since the agenda of the protest was vague and demands were unarticulated, the very experience of gathering and being together became the important goal, not just the means, of the movement. The eventful experience of unity, shaped by the sudden break with routine, was the achievement of all the protesters (Zhuravlev, 2014).

However, encouraged by their experience of the public events, some of the people involved in them, sensing that the protest rallies were becoming less and less meaningful, decided to organize neighborhood associations that, on the one hand, would enable them to realize their desire to engage in public work, and, on the other, render collective action more specific, tangible, and effective. Activists got together not in order to solve an urgent problem, but because they had already been whipped up by the energy of public protest; the specific agenda was secondary. So, despite the outward resemblance to ordinary local activism (after all, the post-Bolotnaya Square local groups engaged with the exact same issues: the deforestation of public parks, runaway urban development, and road construction that impinged on forests and neighborhoods), they were engaged in a different sort of activism. It was not provoked by an invasion of the familiar realm, as had been typical in Russia in the cases described by Gladarev, Clément, Miryasova, and others (Gladarev, 2011; Clément, Demidov & Miryasova, 2010), but by the experience of the previous mobilization and politicization. This reverse genesis of local activist groups—not from issue to action, but from action to specific issues—suggests a transformation in the meaning and purpose of social activism.

As they became involved in local activism, the protesters rediscovered their own habitats, their own neighborhoods and towns. On the one hand, neighborhoods took on more specific shapes; their borders and geographies emerged. On the other hand, these were not geographies of familiar places, but geographies of issues in need of solutions and action. More important, however, is the fact that the rediscovered neighborhoods are not just places or constellations of issues, but have come to be seen as civil society in miniature. The neighborhoods were seemingly repopulated with “citizens.” Thus, post-protest activism integrated the local and familiar sphere of urban collective action with the nationwide and public sphere of contentious politics.

Politics and Getting Real Things Done

Continuing this line of our analysis, let us proceed to study yet another hybrid that fused apolitical small deeds, regarded in pre-Bolotnaya Square activism as part of familiar space, and the political, which was outside this space.

Alexander argues that high-profile political events cause a re-articulation of fundamental cultural codes (Alexander, 2003). Elaborating and simultaneously criticizing Alexander’s approach, Eliasoph and Lichterman have called for a pragmatic way of analyzing cultural codes. The sociologists argue that in different circumstances and different communities people understand, articulate, and give meaning to the prevalent cultural oppositions in different ways (Eliasoph and Lichterman, 2003). Our study has also shown that when new local groups are launched, politics and specifics can be combined and evaluated in different ways in the rhetoric of activists.

First, the juxtaposition between politics and getting real things done could be normative. In this rhetoric, the solving of specific problems was conceived as valuable in itself and an end in itself to be pursued and “the political” is associated with aggression, abstraction, showing off, destruction, propaganda, critique, ideology, and chatter, while getting real things done is bound up with specificity, meaningfulness, goodness, usefulness, practicality, effectiveness, familiarity, mundaneness, peace, and realism. On the contrary, another discourse, based on the opposition between politics and specifics, endowed the political with a positive meaning. In this discourse, getting real things done generally functioned as a tactic that legitimized collective action, which inevitably had a political dimension. Juxtaposing politics to real things in favor of either of the former or the latter, both types of discourse were superseded, during the evolution of the activist groups, by a new, third discourse that united politics and specifics in a single frame.

By becoming involved in various campaigns and projects (for example, municipal district council election campaigns), members of the new groups do real things and take part in opposition politics at the same time. Real things and politics had fused. This evolution caused the category of the political to take on a new meaning. In later interviews, activists willingly talked about politics as something essential, vital, and beneficial, emphasizing, however, that they were talking about “good” politics rather than “bad” politics, about grassroots politics, say, as opposed to official politics. Thus the opposition between politics and specifics, which had been the foundation of the culture of apoliticism, has been transformed into an opposition between good politics and bad politics. This major social change—the transformation of political culture—has been an effective tool in the eventful politicization of local activism.

Biographical Hybrids

The Bolotnaya Square movement produced not only new combinations of the private and public realms and thus redefined the very meaning of the word “politics”. It has also entailed the emergence of hybrids of a completely differently kind: the combination in the lives of activists of elements of know-how which had existed independently of each other prior to the large-scale protests.

On the one hand, people have met others in the post- Bolotnaya Square local groups whose lives would hardly have intersected outside Bolotnaya Square. The sociologist Olivier Fillieule would have called them people with different “activist careers.” The analysis of the biographical interviews with members of post-Bolotnaya Square local groups revealed four different activist careers, leading to involvement in the new local activism—ordinarily, these four careers rarely intersect and shape different social institutions: apolitical professionalism; apolitical volunteer social organizations, focused on helping individuals but not on changing the ground rules; professional big-time politics, as reflected in the competition among political parties; and “kumbaya” oppositionism in the social networks. During the popular protests of 2011–2012, representatives of these different careers came together in the same place, and later, thanks to the event of Bolotnaya Square, they wound up in the same local groups. The intersection of these careers within the new local activism partly shaped its hybrid nature. On the other hand, aside from bringing together activists whose paths had not previously crossed, the event of Bolotnaya Square also facilitated the fusion of various experiences and know-hows in the same careers. People who, on the eve of Bolotnaya Square, were going through personal crises and could not find their place in life discovered their calling in post-Bolotnaya Square activism. People who had devoted their lives to professionalism in a particular field and had been passionate about it for its own sake for many years at some point realized that local activism would help them become better professionals, and their professional skills make them better activists.

Conclusion

In our article, we have shown that the unity felt by different people as a result of their experience at the Bolotnaya Square protests, the sense of solidarity that guided the sudden collective action of thousands of people, later spread to the neighborhoods of Moscow and Petersburg. The neighborhoods gave birth to local activist groups that, although they resemble conventional local Russian activism, are fundamentally different from it. We analyzed the mechanics of this social transformation, showing how the experience of the event and the inertia of the eventful collective experience, channeled to the scale of neighborhoods and taking root in the concrete practice of doing real things, has gradually altered political (or, rather, apolitical) culture. The activists in these groups have established a stable, reproducible group style (Lichterman and Eliasoph, 2003) that combines the apolitical and the political—the realm of the familiar and the public sphere, the ethic of small deeds and oppositionism, a belief in self-evident facts and political campaigning.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Jeffrey (2003). The Meanings of Social Life: A Cultural Sociology. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bennett, Elizabeth, Cordner, Alissa, Taylor Klein, Peter, Savell, Stephanie, & Gianpaolo Baiocchi (2013). “Disavowing Politics: Civic Engagement in an Era of Political Skepticism.” American Journal of Sociology 119.2: 518–548.

- Clément, Carine, Miryasova, Olga, & Andrei Demidov (2010). Ot obyvatelei k aktivistam. Zarozhdaiushchiesia sotsialnye dvizheniia v sovremennoi Rossii. [From ordinary folk to activists: emergent social movements in modern Russia]. Moscow: Tri kvadrata.

- Della Porta, Donatella (2008). “Eventful Protests, Global Conflicts.” Journal of Social Theory 9:2: 27–56.

- Eliasoph, Nina (1996). “Making a Fragile Public: A Talk-Centered Study of Citizenship and Power.” Sociological Theory 14.3: 262–289.

- Eliasoph, Nina and Paul Lichterman (2003). “Culture in Interaction.” American Journal of Sociology 4.108: 735–794.

- Fillieule, Olivier (2010). “Some Elements of an Interactionist Approach to Political Disengagement” Social Movement Studies 9.1: 1–15.

- Gladarev, Boris (2011). “Istoriko-kulturnoe nasledie Peterburga: rozhdenie obshchestvennosti iz dukha goroda” [Petersburg’s cultural heritage: the emergence of a public from the city’s spirit]. In Ot obshchestvennogo k publichnomy [From the social to the public], ed. Oleg Kharkhodin, 69–304. St. Petersburg: EUSP Press.

- McAdam, Doug and William Sewell (2001). “It’s about Time: Temporality in the Study of Social Movements and Revolutions.” In Silence and Voices in the Study of Contentious Politics, ed. Ronald Aminadze, Jack Goldstone, Doug McAdam, Elizabeth Perry, William Sewell, Sidney Tarrow & Charles Tilly, 89–125. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Prozorov, Sergei (2008). “Russian Postcommunism and the End of History.” Studies of Eastern European Thought 60: 207–230.

- Sewell, William (1996). “Historical Events as Transformations of Structures: Inventing Revolution at the Bastille.” Theory and Society 25.6: 841–881.

- Thévenot, Laurent (2001). “Pragmatic Regimes Governing the Engagement with the World”. In The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. Ed. Theodor R. Schatzki, Karen Knorr Cetina, & Eike von Savigny, 64–82. London & New York: Routledge.

- Thévenot, Laurent (2015). “Voicing Concern and Difference: From Public Spaces to Common-places.” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 1.1: 7–34.

- Yerpyleva, Svetlana (2018). “From Nationwide Protest to Local Initiatives: Activists’ Careers and Socialization Process”. Forthcoming

- Zhuravlev, Oleg (2014). “Inertsiia postsovetskoi depolitizatsii i politizatsii 2011–2012 godov” [The inertia of post-Soviet depoliticization and politicization during 2011–2012]. In Politika apolitichnyh: Grazhdanskie dvizheniia v Rossii 2011–2013 godov [The politics of the apolitical: civic movements in Russia, 2011–2013], ed. Maxim Alyukov et al., 27–70. Moscow: Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie.

About the Authors

Oleg Zhuravlev is a sociologist, a researcher and professor in the School of Advanced Studies, University of Tyumen

and a researcher with the Public Sociology Laboratory (PS Lab).

Natalia Savelieva is a sociologist, researcher and professor in the School of Advanced Studies, University of Tyumen

and a researcher with Public Sociology Laboratory (PS Lab).

Svetlana Erpyleva is a sociologist, a researcher and instructor in the School of Advanced Studies, University of Tyumen

and a researcher with Public Sociology Laboratory (PS Lab).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.