Defeat by Annihilation: Mobility and Attrition in the Islamic State´s Defense of Mosul

19 Apr 2017

By Michael Knights and Alexander Mello for Combating Terrorism Center (CTC)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made in external pageVolume 10, Issue 4call_made of the external pageCTC Sentinelcall_made by the external pageCombating Terrorism Centercall_made in April 2017.

Abstract

The Islamic State’s defense of Mosul has provided unique insights into how the group has adapted its style of fighting to dense urban terrain. While the Islamic State failed to mount an effective defense in the rural outskirts and outer edges of Mosul, it did mount a confident defense of the denser inner-city terrain, including innovative pairing of car bombs and drones. The Islamic State continues to demonstrate a strong preference for mobile defensive tactics that allow the movement to seize the tactical initiative, mount counterattacks, and infiltrate the adversary’s rear areas. Yet, while the Islamic State has fought well in Mosul, it has also been out-fought. Islamic State tactics in the final uncleared northwestern quarter of Mosul are becoming more brutal, including far greater use of civilians as human shields.

The battle of Mosul is an unparalleled event in the history of the current war against the Islamic State, not only because Mosul is the largest city to be liberated from the group or because of the unprecedented size of the security forces concentrated against the Islamic State. It also unprecedented because, for the first time, the Islamic State has no nearby sanctuary to which it can retreat. Mosul is the capital of the Islamic State in Iraq, and the group draws significant prestige from occupying Iraq’s second largest city. Unlike in Tikrit, Ramadi, or Fallujah, the Islamic State defenders of Mosul are genuinely cut off from escape; they cannot simply mount a temporary resistance and then slip away to nearby Islamic State refuges to fight another day. Mosul is instead a Kesselschlacht (cauldron battle) in which the group is encircled and cannot hope to achieve a cohesive breakout at the end of the battle, as was attempted at Fallujah. The end of the Islamic State’s occupation of Mosul is drawing near, and it could end with the group mounting a ferocious (and atypical) last stand in northwestern Mosul.

With at least one quarter of Mosul still under Islamic State control, it is too soon to uncover the full story of the liberation of western Mosul. Therefore, this article will largely focus on the completed battle for east Mosul that raged between October 20, 2016, and January 24, 2017. During that 97-day fight, the Islamic State defended an area of 500 square miles, including 47 east Mosul neighborhoods with an urban area of just under 50 square miles. In a previous study of the defensive style of the Islamic State, the authors observed that Mosul is probably too big for the Islamic State to mount a perimeter defense capable of excluding a large attacking force due to the group’s relatively small numbers. The authors also stressed the “tactical restlessness” of Islamic State units—the compulsion of local Islamic State leaders to mount active, mobile defenses that were disruptive to attackers but which also led to high levels of attrition within the group’s ranks. This update will look at what aspects of the Islamic State’s “defensive playbook” remain the same and what aspects have changed to meet the conditions and challenges of defending Mosul.

East Mosul’s Rural “Security Zone”

Operational factors and the geography of Mosul shaped the design of the Islamic State’s defense of the city. The bisection of Mosul by the Tigris River (and the likelihood that all five bridges might be denied to the Islamic State) meant that the group needed to build stockpiles of munitions, plus IED and car bomb assembly workshops, on both sides of the river. Mosul was always likely to be fully encircled during the course of the battle, and in any case, the rural outskirts are lightly populated with open terrain, making them of limited use as long-term defensive bastions (in contrast to the dense palm groves outside Ramadi).a These factors meant that the Islamic State could not hope to mount a long-lasting defense in the east Mosul outskirts. Instead, it employed an economy of force effort that bolstered small numbers of infantry with extensive defensive IED emplacements and prepared fighting positions, tunnel complexes, and mortars with pre-surveyed defensive targets.

Some towns were “strong-pointed” to act as breakwaters against the advancing security forces. One example was Tishkarab, a small village nine miles east of Mosul, which held out for several days in mid-October against strong Kurdish forces directly supported by coalition special forces and on-call Apache gunships and fixed-wing airpower.b At Abbasi, 15 miles southeast of Mosul, Iraqi Army forces pushing up the Mosul-Kirkuk highway ran up against a dense cluster of bunkers, tunnels, IED-rigged obstacles, and an anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) ambush zone. The result was that insurgents dug in at Abbasi held up the Iraqi security forces (ISF) advance for several weeks.

A final component of the Islamic State security zone outside Mosul was its intense drip-feed of suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive devices (SVBIEDs) into the strongpoint battles. In a single day in the third week of October 2016, the Islamic State reportedly deployed 15 up-armored truck bombs against an Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF) column advancing toward Bartella, most of which were destroyed by main-gun rounds from the M1 Abrams tanks spearheading the column.c On the same date, Kurdish Zerevani forces pushing into Tishkarab ran into a stream of up-armored SVBIEDs racing toward their positions, including some large five-ton truck bombs. Despite last-minute airstrikes called in by Coalition JTACs that intercepted most of the Tishkarab SVBIEDs, the tremendous shock effect of these high-yield devices degraded Kurdish morale and inflicted substantial casualties.d

The actions in Mosul’s outer security zone were supported by the extensive use of operational and tactical smokescreens. Strongpoints like Tishkarab, Bartella, and Bashiqa were covered by a thick haze caused by scores of piles of burning tires. This obscuration was surprisingly effective because it made positive target identification more difficult and created additional hurdles for aerial weapons release under the rules of engagement prevailing at the time.e A broader pall of toxic smoke from the sabotaged Qayyarah oil wells and Islamic State-ignited sulphur piles at Mishraq covered the southern approaches to Mosul.

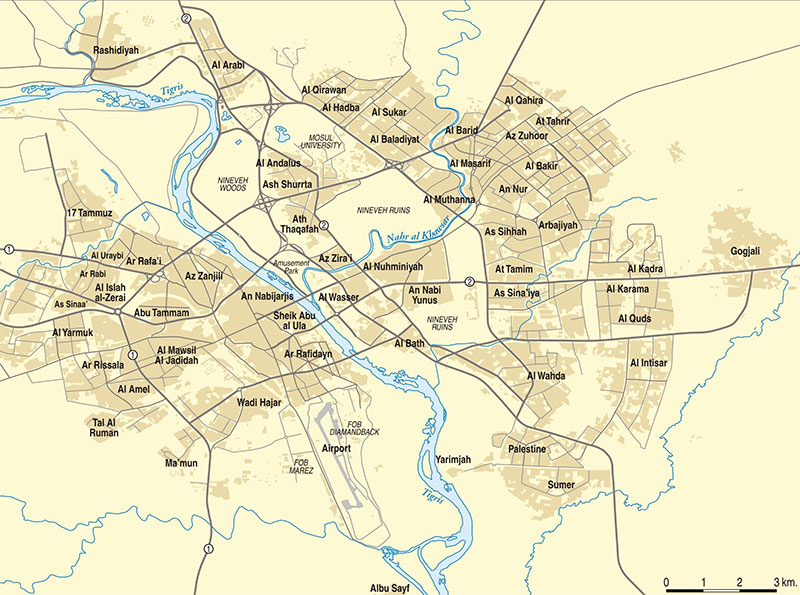

Outer Crust Urban Defenses

As in previous urban battles in Ramadi and Fallujah in 2015-2016, the Islamic State’s defense of Mosul was concentrated along a defensive “crust” roughly two to three kilometers (one to two miles) in depth running along the outer neighborhoods of city. In east Mosul, the Islamic State defensive belt ran from the al-Sukar and al-Hadba residential districts in the north through al-Tahrir, Zahra’a (just northeast of al-Bakir on the map), Samah, and the densely built up al-Karama district, where the Erbil highway enters Mosul, then flowing down to al-Intisar and Sumer in the south. In west Mosul, this defensive belt ran from the Tanak (area just west of al-Yarmuk on the map) and Tal al-Ruman districts, where the highway from the Islamic State stronghold at Muhallabiyah enters the city, down to the Wadi Hajar and Jawsaq neighborhoods north of Mosul airport and the Camp Ghizlani military complex. The Islamic State clearly had an accurate appreciation of the vectors from which the assault on Mosul were most likely to come (and subsequently did).

In these districts, the Islamic State used the months preceding the ISF assault to build up defensive zones covering several contiguous urban blocks. Local residents were ejected,f and the outer neighborhoods were honeycombed with prepared fighting positions and caches of explosives and ammunition. Insurgents “mouse-holed” rows of houses to allow them to move rapidly between buildings while evading airstrikes. The urban equivalent of tunnels, this mouse-holing signaled the Islamic State’s intent to fight a battle of movement within neighborhoods, including the re-infiltration of areas cleared by the security forces. Small four- to five-man squads, usually with one heavy machine-gun and one RPG gunner, were distributed every few hundred meters of frontline, grouped into platoon-sized 20- to 30-man neighborhood fighting cells. These cells drew on the extensive network of pre-positioned ammunition caches to sustain their local fights.

Unlike in Ramadi, which was marked by high-density improvised minefields made of IEDs, insurgents do not appear to have made extensive use of static IEDs in urban Mosul. As in Fallujah, the lack of dense IED minefields in Mosul city was probably due to the civilian population still in place and the high volume of civilian traffic until the very start of the battle.g The lack of improvised minefields could have also been a reflection of changing ISF tactics in the battles before Mosul, where motorized infantry units bypassed IED minefields and moved on to their objectives, leaving such devices to be cleared by follow-on forces. Other static defense features used by the Islamic State also did not greatly impact the Mosul battle. In east Mosul, the group constructed a new earthen berm that ran along the edge of the urban area, while in southwest Mosul the group built a more substantial berm line that traced the path of the old Saddam-era anti-tank trench, which had been improved by the coalition in 2008. Roads were obstructed by roadblocks, including T-wall barriers, parked cars, and rubble berms. These obstacles did not greatly aid the defense and were only effective when they were covered by fire, typically snipers, mortars, or anti-tank weapons.

Islamic State anti-tank defenses were particularly effective in the rural belts and at the outer edge of Mosul city.h Humvee columns spearheaded by M1 Abrams tanks ran into a dug-in, firmly anchored Islamic State defense supported by urban anti-tank guided missile (ATGM) positions. The Islamic State seems to have saved up a large stock of ATGM ammunition and distributed it throughout concealed positions in the outlying villages and outer edges of the city neighborhoods, turning the peripheries of Mosul city into ATGM ambush zones.i The flurry of ATGM strikes against buttoned-down tanks during the initial probes into east Mosul made the Iraqi Army reluctant to push its armor further into the urban area, leaving columns of soft-skinned Humvees to advance without armor support. The Islamic State achieved an important goal for much of the east Mosul battle: to separate enemy tanks and infantry from cooperating in the street-to-street fighting.

Defending the Mid-Density Inner City

The Islamic State could not prevent the security forces from penetrating into the city, whereupon the nature of the defense changed again. The Islamic State adopted a mobile defense after being evicted from the fortified outer crust of east Mosul. This mobile defense consisted of aggressive and well-supported counterattacks against exposed ISF penetrations—a continuation of the “tactical restlessness” observed by the authors in their earlier piece on the group’s “defensive playbook.” Small squad and platoon-sized teams of insurgent fighters repeatedly infiltrated cleared areas and launched night counterattacks and ambushes, frequently exploiting low-visibility weather conditions, including heavy rain and dust storms.j

In some cases, ISF columns penetrated into the urban area but were then broken up and isolated in a series of large ambushes in the urban interior. In late October 2016, a column of the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF) Salahuddin Regional Commando Battalion ran into a large ambush in the Karkukli neighborhood after penetrating about two miles into east Mosul. As documented by a CNN film crew, the unit was ambushed, isolated, and under sustained attack for over 24 hours, suffering heavy personnel and vehicle losses.

In early December 2016, an armored ISF strike force launched a “thunder run” from outer Intisar district toward the Salam Hospital near the Tigris. The column broke through to the hospital complex but was then hit by multiple suicide car bombs and intense rocket-propelled grenade and small-arms fire. The company-sized unit was cut off for over 24 hours, suffering heavy casualties.

Most recently, in March 2017, the 2nd Emergency Response Brigade of the Ministry of Interior launched a “thunder run” through Islamic State-held streets of west Mosul to reach the Nineveh Provincial Council compound. The Islamic State counterattack on the compound involved the use of Islamic State bulldozers (covered by sniper and RPG fire) to breach perimeter T-walls, allowing insurgent fighters to assault the compound. The retreating Federal Police convoy was struck with several suicide car bombs released from nearby hide sites.

The VBIED/Drone Nexus in Urban Fighting

The SVBIED was the “momentum breaker” most frequently used by the Islamic State to blunt ISF penetrations into the inner city. The Islamic State quickly learned that this tactic was much more effective in the dense urban terrain than it had been in the open areas outside Mosul. In the initial phase of the urban battle, the Islamic State was able to generate up to 14 SVBIED attacks per day, drawing on an essentially limitless supply of civilian vehicles looted from car dealerships or the local population, some even donated by residents. Vehicles were converted to car bombs at industrial-scale manufacturing workshops dispersed around the Mosul urban area.k The devices were then moved to forward hide sites in residential areas, such as houses with garages or covered driveways, where they were concealed from coalition sensors.l

ISF columns moving slowly through the dense urban terrain faced SVBIEDs released from hide sites at high speed through narrow side streets to detonate against their flanks. The tight urban spaces dramatically reduced the ISF’s reaction times and ability to engage SVBIEDs with tank main gun rounds or anti-tank guided missiles, forcing security forces to rely on less effective close-range AT-4 rockets and RPGs. In some cases, parked SVBIEDs were driven directly out of garage hides into passing ISF columns.

The SVBIED cat-and-mouse game in Mosul evolved rapidly. The ISF blockaded streets with wrecked cars and T-walls, but the Islamic State stayed one step ahead by using camera-equipped hobby drones to bypass roadblocks and guide suicide car bombs onto targets using live video feed and radio. SVBIEDs were also regularly sent out in pairs, with the first car bomb breaching any defensive berm or barrier, allowing the second to access the target.m Local Iraqi Islamic State fighters familiar with the neighborhoods were also sent out on motorcycles to accompany and guide in car bombs. The Islamic State adapted to coalition strikes on UAV launch sites and control stations by switching to mobile UAV controller teams moving around the city on motorcycles.

The Islamic State also changed the visual signature of its car bombs. SVBIEDs were painted with dun-colored camouflage to blend in with Mosul’s urban terrain and were fitted with improvised armor plating, allowing them to shrug off small-arms fire. By February 2017, insurgents had further adapted by “camouflaging” up-armored SUV or pickup SVBIEDs, painting fake windows and tires and bright colors to resemble conventional civilian vehicles in an effort to confuse ISF and overhead coalition intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR). One armored SVBIED was even mocked up as a taxi, replete with an accurate paint job and exterior features.n

Infiltration Attacks into Cleared Areas

A feature of the Islamic State defense of Mosul has been its investment of effort into the destabilization of liberated parts of the city. One method has been the use of SVBIED “deep strikes” into seemingly secure areas of Mosul. In late December, three up-armored SUV suicide car bombs passed through several cleared neighborhoods and hit a market and police checkpoint in the Gogjali district, a six-mile drive into the eastern outskirts of Mosul. UAV route reconnaissance likely aids these types of missions by diverting car bombs around ISF checkpoints.

Even after the Islamic State lost all of its neighborhoods in east Mosul, the group continued to send night raids across the Tigris, linking up with Islamic State fighters still present in the east bank in an effort to disrupt the ISF occupation of east Mosul. In one case, Islamic State infantry crossed the Tigris and made a five-mile penetration around Mosul’s outer southeastern edge to attack ISF rear areas. The Islamic State’s remarkable tactical energy at the small-unit level has been sustained even through the ongoing fighting in west Mosul, where insurgent fighting cells have continued to undertake night raids and sniper attacks behind the ISF front lines.o

The Islamic State has also made extensive use of rocket and mortar fires against liberated neighborhoods to create mass civilian casualties and disrupt the return to normal civilian patterns of life. Armed drones have now been added to this effort, dropping grenade-sized munitions on schools and humanitarian aid distribution centers to maximize civilian casualties and disrupt ISF stabilization efforts.

Camera-equipped quadcopter hobby UAVs have also proven effective at attacking the ISF and have been used since at least the first week of November 2016. The volume of UAV-dropped munition attacks grew from pinpricks to persistent harassment over the course of the east Mosul battle. Having access to real-time targeting data, the Islamic State effectively targeted small clusters of ISF personnel, Humvees, and tanks during both the daytime and at night. By February 2017, ISF were reportedly sustaining up to 70 UAV attacks per day, and while these attacks caused few casualties, they were a sap on morale.

Assessing the Islamic State Defense of East Mosul

On one level, it is difficult not to be impressed by the confident defense that the Islamic State has mounted in Mosul. The city is large, with a 32-mile perimeter and over 70 neighborhoods. Well over 50,000 security forces took part in the offensive to clear Mosul, with two-thirds of these forces deployed to eastern Mosul. Persistent coalition surveillance and airstrikes supported the Iraqi forces, day and night.

Yet, the Islamic State never faced the full weight of the Iraqi security forces. The Kurdish Peshmerga were only asked to participate in shallow breaching of the security zone to a depth of two to three miles. In the view of the authors, based on synthesis of hundreds of pieces of individual battle reporting and imagery, the Iraqi Counter-Terrorism Service forces proved to be the only reliable and resilient attacking force. The various axes of advance were poorly coordinated. As a result, for most of the battle, the Islamic State could largely focus its efforts on just one out of the five main axes of attack—that of the Counter-Terrorism Service forces on the eastern axis. The authors calculate that between 450 and 850 Islamic State fighters were engaged at any one time in fighting in east Mosul.p Iraqi combat forces actively engaged in eastern Mosul city probably never exceeded 6,000 during the first 12 weeks of the battle, and they numbered considerably less during the first phase in November 2016.q Thus, the Islamic State defenders were never overwhelmingly outnumbered at the point of contact.

Viewed with clear eyes, the battle for east Mosul provides many lessons about the Islamic State’s evolving defensive playbook and its strengths and weaknesses. The Islamic State has historically projected and sustained defensive power from the rural zones around contested cities, leaving the inner cities as an “economy of force” effort that relied on improvised minefields covered by very small numbers of defenders. In Mosul, the formula was turned on its head: the rural operations were short-lived and not very successful. The inner-city fighting was the key, and thus Mosul may be the Islamic State’s first true defense of a city.

The Islamic State rural security zone proved valuable to the defense in areas where the attacking forces were hesitant and easily deterred, notably against the Iraqi Army forces on the northeastern and southeastern axes. The incorporation of anti-tank guided missiles into rural strongpoints, covered obstacles, and outer crust defenses was genuinely effective in separating Iraqi motorized infantry from its supporting armor. But the security zone proved ineffective at delaying high-quality attacking troops such as the Counter-Terrorism Service, the most effective units of the Peshmerga, and their attached coalition special forces. Within just 11 days, the ISF had a secure beachhead on the eastern edge of Mosul city. SVBIED counterattacks, while fierce, were largely defeated by airpower in the open suburbs. Even the well-prepared defensive belt along the eastern edge of Mosul city did not blunt the ISF attack, which employed new tactics to bypass strongpoints.

As the battle spread into the interior of east Mosul city, the size of the battlespace increased, including both high-density urban neighborhoods and large tracts of open land set aside for archaeological sites and parks. In this environment—where Islamic State and Iraqi forces both employed a low forces-to-space ratio—the battle was mobile and fluid. This allowed the Islamic State to take back the tactical initiative periodically and to exercise the aggressive counterattacking instincts of its local commanders. The SVBIED-led counterattack regained its potency as a tactic in this environment, and the Islamic State innovated with its use of camouflaged car bombs, “deep strike” SVBIEDs sent into the stabilized areas, and the use of UAVs for real-time target and route reconnaissance. The Islamic State stepped up its long-range raids and armed UAV attacks, further indications that the group is never comfortable unless it is tactically on the offensive. All of the Islamic State’s concealment activities—night-fighting, use of bad weather, smokescreens, tunnels, mouse-holing, and camouflage—are aimed at restoring tactical mobility to the battlefield under conditions of enemy air supremacy.

Adaptation to Islamic State Tactics

The Islamic State has fought well at Mosul, but it has also been out-fought in the battle and is on the verge of defeat. A gradual opening of multiple fronts against the Islamic State is certainly one reason, drawing more Iraqi forces into the fight, but a more important factor is that the ISF-coalition partnership has adapted and partially neutralized all of the Islamic State’s tactics.

After a series of devastating SVBIED strikes on ISF columns and clusters of parked vehicles in the initial phase of the urban fight, the security forces rapidly learned to fortify-in-place by using bulldozers to throw up earth berms, putting up roadblocks made up of abandoned civilian vehicles, and positioning Abrams tanks at intersections.r The ISF also increasingly began calling in “terrain denial” airstrikes to crater roads to prevent SVBIEDs that were stalking their columns along parallel streets from ramming their vehicles.

In December 2016, a series of coalition airstrikes selectively destroyed replaceable bridge sections and cratered access ramps on all five of the Tigris bridges, interdicting the flow of car bombs from car bomb factories in the west to attack zones in east Mosul and forcing the Islamic State to use up its remaining VBIED reserve in the east half of the city. Airstrikes destroyed car bomb workshops and hide sites inside Mosul city. By the first week of January 2017, commanders had begun to note a decline in the Islamic State’s ability to generate SVBIED attacks, which dropped from an average of 10 per day (with half striking home) to one to two per day (with roughly less than one in six penetrating to their target). Soft-skinned civilian vehicles with lower explosive yields were also increasingly common instead of up-armored trucks or SUVs.

Attrition and more coordinated ISF-coalition operations broke the resistance of the Islamic State in eastern Mosul in the second week of January 2017. Coordination between Islamic State neighborhood fighting cells began breaking down under the pressure from the multiple ISF lines of advance, coalition airborne jamming platforms, and intensified precision airstrikes. The shrinking Islamic State defensive pocket in east Mosul could not maneuver, lacked fortified positions, and ran out of car bombs.

The volume of armed UAV attacks was also reduced when the United States deployed counter-drone jamming systems up to the frontline. ISF and embedded coalition special operators also adapted to Islamic State route reconnaissance drones by monitoring insurgent two-way radio traffic and using Iraqi and coalition hand-launched UAVs to track moving car bombs and call in airstrikes.

The Battle Ahead

On January 24, 2017, Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi declared the complete liberation of eastern Mosul, 97 days after the operation had begun. The west Mosul clearance operation is ongoing at the time of writing and has seen fairly rapid ISF advances into a nearly half of western neighborhoods in its first 50 days, albeit bypassing some of the denser old city areas whose narrow streets preclude the use of armored vehicles and fire support. The advance has slowed as Islamic State fighters are compressed into the densely populated northwest of the city, an area two miles by three miles, where Islamic State tactics have become more desperate. Iraqi and coalition tactics have also become more costly in civilian lives, in part due to the Islamic State’s increasing collocation of civilians with Islamic State car bomb hide sites, fighting positions, and rocket launch sites. The Islamic State’s first real defeat by annihilation, its first true “last stand” battle, appears to be now unfolding in northwest Mosul. If the other Islamic State capital, the Syrian city of Raqqa, were to be encircled, a similar last-stand battle might also ensue, possibly catching more Islamic State fighters in its net but guaranteeing a tougher, more brutal battle first to secure the city.

Liberation does not, of course, necessarily equate to security, and there have been ongoing Islamic State attacks inside eastern Mosul since January. Some of these are from bypassed Islamic State fighters; others are deliberate infiltrations across the river from Islamic State-held areas. Drone-delivered bombings and indirect fire are also used to harass the eastern half of the city. Furthermore, resentment is growing among civilians over the arrest of eastern Mosul military-age males in the search for those complicit in Islamic State crimes. In both the eastern and (eventually) the western halves of Mosul, there is a need to develop and use a consensus-based security decision-making body that represents all the city’s factions. Residual Islamic State elements need to be combed out with surgical counterterrorism and counter-organized crime operations (as mafia-type activity is typically how the Islamic State and its forebears have rejuvenated after setbacks in Mosul). The key risk is that Mosul’s distance—physical and political—from Baghdad will result in the same neglect of local security dynamics that opened the door for the Islamic State in 2014. Salafi terrorists have been defeated in Mosul before, only to mount strong comebacks in 2005, 2007, and 2014. The story of the Islamic State in Mosul is far from over.

Substantive Notes

[a] The terrain in the Fallujah-Ramadi corridor is characterized by dense groves and a sprawl of medium-density villages and rural areas. In contrast, the area in the Nineveh plains surrounding Mosul is characterized by relatively open terrain with small, scattered villages. The Mosul-Erbil highway corridor gradually coalesces into a continuous, built-up area of mechanic garages, scrap yards, and shops as it nears the eastern edges of Mosul.

[b] Author Michael Knights observed the Tishkarab battle from Peshmerga and U.S. positions, including discussions between U.S. Joint Terminal Attack Controllers.

[c] The authors’ synthesis of open source reporting, with duplicates removed, resulted in 15 separate credible claims of car bombs detonating on the eastern axis. (Indeed, one author heard multiple car bombs detonating per hour over a four-hour period on that axis in late October). Also see Bryan Denton, “ISIS Sent Four Car Bombs. The Last One Hit Me,” New York Times, October 26, 2016.

[d] Most VBIEDs deployed in the east Mosul fight were SUVs or pickup trucks, capable of carrying around 500-750 kg of explosives. The charges are mostly built from large barrels or jugs filled with ammonium-based homemade explosives, sometimes boosted with military high explosives, anti-tank mines, and propane tanks. See Conflict Armament Research, “Tracing the supply of components used in Islamic State IEDs: Evidence from a 20-month investigation in Iraq and Syria,” February 2016.

[e] Author Michael Knights observed the thickness of the smokescreen over the eastern axis and spoke to coalition and Kurdish officers about the difficulties the smokescreen caused.

[f] In an earlier CTC Sentinel article, “The Cult of the Offensive,” the authors explained that the Islamic State’s approach to Mosul’s civilian population was hard to predict and should be intensively studied. For most of the battle, the Islamic State has made surprisingly little use of civilians as “human shields” in the urban battle, though as its defensive pocket shrinks in northwest Mosul, there are signs of explicit gathering of civilians at strong-pointed buildings and VBIED storage sites. See “Press Release on civilian casualties in west Mosul,” Joint Operations Command – War Media Cell, Republic of Iraq, March 27, 2017.

[g] In the defensive layout seen in Fallujah, Iraqi forces found IEDs were rare in the interior of the city after breaking through the outer belt of IED minefields and defensive fighting positions. Joel Wing, “Iraq Gains Big Victory Over Islamic State In Fallujah In Record Time,” Musings on Iraq, June 20, 2016.

[h] The Islamic State had previously used ATGM “snipers” to pick off significant numbers of Iraqi armored vehicles south of Baiji in April and May 2015. The area is near Hajjaj, where the ISF main supply route passed close to uncleared Islamic State-held villages.

[i] ISF pushing up the Mosul-Kirkuk highway from Kuwayr reported taking daily effective ATGM hits fired from positions inside insurgent-held villages. At least one IA M1 Abrams was disabled by an ATGM during the initial push into east Mosul. The tempo of ATGM strikes tapered off after the first few weeks of the assault as insurgent ATGM stocks were depleted. For an example of ATGM strikes on Iraqi armored vehicles near Mosul, see Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “This video shows ISIS destroying an advanced U.S.-built tank outside Mosul,” Washington Post, November 3, 2016.

[j] In the first phase of the Mosul battle, 14 Iraqi special operations forces personnel were killed in a night counterattack by insurgents after clearing Bazwaya, a hamlet on the eastern axis. Nick Payton Walsh, Ghazi Balkiz, and Scott McWhinnie, “Battle for Mosul: The Iraqi Fighters Closing in on ISIS,” CNN, October 31, 2016.

[k] The main clusters of VBIED manufacturing workshops were located in the Gogjali industrial area on the eastern outskirts, the east Mosul industrial area (As Sina`iya) on the Mosul-Erbil highway, and the Wadi Iqab industrial area in northwest Mosul, marked as As Sinaa’ on the map in this article, north of al-Yarmuk.

[l] Potential VBIED hide sites in residential neighborhoods were marked at the ground level with a spray-painted red circle to guide in drivers ferrying car bombs forward.See Chad Garland, “Stealth is Islamic State’s weapon against coalition’s sophisticated tactics,” Stars and Stripes, March 10, 2017. Some Islamic State tunnel complexes were reported to be wide enough for vehicles to access, suggesting car bombs may be also have been pre-positioned in underground hide sites.

[m] The Islamic State also used armored SVBIED bulldozers that were capable of clearing obstacles. For an excellent, in-depth look at the Islamic State’s urban VBIED tactics, see “The History and Adaptability of the Islamic State car bomb,” zaytunarjuwani.wordpress.com, April 26, 2016.

[n] There were also some reports of suicide car bombs disguised as civilian vehicles flying white flags. For the fake taxi, see the image at https://twitter.com/AbraxasSpa/status/843490681331113985

[o] One such night raid involving an Islamic State sniper equipped with a night-vision scope is described by an Iraqi officer in Susannah George, “In Mosul, a heavy but not crushing blow to IS group,” Associated Press, March 14, 2017.

[p] This estimate is derived from the authors’ calculations of the size of the urban combat area, the number of simultaneous contact zones, and the density of the Islamic State presence at the tactical, neighborhood-level—as reported by ISF personnel and as seen in video footage released by the Islamic State. These frontline fighters were likely supported by an additional several hundred insurgents distributed among dedicated indirect-fire, VBIED, and logistics support cells, as well some rear-area security personnel in neighborhoods behind the frontline.

[q] The main forces employed in east Mosul on the eastern axis were the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Iraqi Special Operations Forces brigades, plus some supporting Iraqi Army forces from the 1st and 9th divisions. All Iraqi units are chronically undermanned, and an estimate of 6,000 combat troops present on the ground would be generous.

[r] At least one M1 Abrams tank was rendered inoperative in east Mosul when a car bomb drove directly into the tank. “ISIS suicide bomber takes out Iraqi tank in battle for control of Mosul,” Associated Press, November 17, 2016.

About the Authors

Dr Michael Knights is the Lafer Fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. He has worked in all of Iraq’s provinces, including periods embedded with the Iraqi security forces. Dr. Knights has briefed U.S. officials on the resurgence of al-Qa`ida in Iraq since 2012 and provided congressional testimony on the issue in February 2017. He has written on militancy in Iraq for the CTC Sentinel since 2008. Twitter: @mikeknightsiraq

Alexander Mello is the lead Iraq security analyst at Horizon Client Access, an advisory service working with the world’s leading energy companies. Twitter: @AlexMello02

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.