Africa Uprising? The Protests, the Drivers, the Outcomes

6 Dec 2016

By Valerie Arnould, Aleksandra Tor and Alice Vervaeke for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 2 December 2016.

Political and social protests across the African continent have garnered much attention over the past year. Ethiopia has been rocked by mass street protests across its Oromia and Amhara regions over grievances about political exclusion, which gained global prominence when an Ethiopian athlete at the Olympic Games in Brazil made a gesture (wrists crossed above his head) which has come to symbolise the demonstrations. Elsewhere, South Africa has witnessed large-scale and persistent student unrest at campuses across the country over tuition fees and demands to ‘decolonise’ universities, resulting in significant disruption to the academic year and damage to property. Meanwhile, highly-contested electoral processes saw protests break out in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Gabon, and Uganda. Even countries such as Chad, Angola and Zimbabwe – which traditionally see few protests because of the tightly controlled nature of the public space – experienced large-scale public unrest.

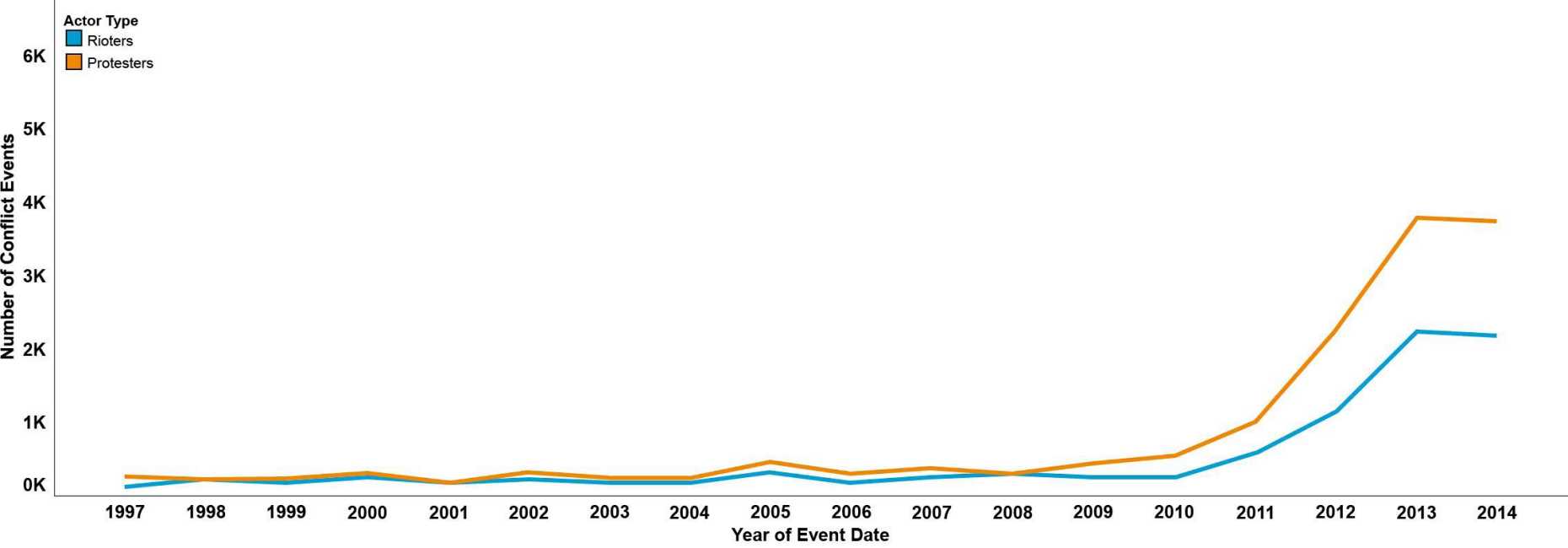

These developments chime with similar mass anti-government protests in previous years in countries such as Burundi, Senegal and Burkina Faso. In fact, data suggests that the number of popular protests in Africa has increased significantly since the mid-2000s, reaching its peak in recent years, and that this rise has affected the entire continent.

To what extent can this surge challenge sitting governments or even be the harbinger of broader social and political change on the continent?

The historical pattern

While the recent spike is notable, Africa has a long history of mass street protests. Colonial powers faced opposition from national liberation movements, as well as strikes by labour unions and street demonstrations by disenfranchised urban populations. After independence, both political protests and economic strikes continued intermittently, driven by discontent over the dominance of one-party rule and dictatorships, as well as worsening economic conditions and draconian austerity measures.

Protests gained particular prominence in the late 1980s and 1990s, and have been credited with helping to bring about a democratic shift across the continent. Between 1989 and 1994, 35 countries moved from one-party rule to multi-party elections, resulting in changes of leadership in 18 countries (compared to none before 1990, with the exception of South Africa and Mauritius).

Recent protests do not, therefore, represent a radically new development for Africa. Rather, they fit into a historical pattern of popular mobilisation to express discontent with the performance of governments. At their core, they are expressions of unmet popular aspirations for change and of the inability or unwillingness of many countries to provide a serious response to the grievances which triggered earlier waves of protest.

The latest protests started in the late 2000s and spiked dramatically from 2010-2011 onwards. In part, the protests overlapped with the ‘Arab Spring’, suggesting the latter may have had a contagion effect across the continent. However, protests had already started increasing since 2005, well ahead of the Arab Spring, which suggests that deeper dynamics are at play. Popular unrest has taken different forms, varied in scale, and occurred both at the local and national level. They include street demonstrations against rising food prices and the cost of living (Chad, Guinea, Niger), strike actions over arrears in wage payments and labour disputes (Botswana, Nigeria, South Africa, Zimbabwe), pro- tests over rigged elections or attempts by leaders to extend their constitutional term limits (Burkina Faso, Burundi, DRC, Gabon, Togo, Uganda), student protests (Uganda, South Africa), and outbreaks of unrest over police violence, extortion, corruption and impunity (Chad, Kenya, Senegal, Uganda). What many of these popular protests have in common is that they are driven by deep-seated frustration with the economic and political status quo.

Africa rising?

Rising economic growth on the continent over the past two decades led to optimistic narratives about ‘Africa rising’ as real GDP increased by around 5% each year since 2000. However, this has not translated into a substantial reduction in economic inequality, (youth) unemployment, a reliance of large sections of the population on the informal sector, and overall poverty. At the same time, data from Afrobarometer, a pan-African research network, suggests that while there has been an increase between 2002 and 2010 in the demand for democracy, there is also a widespread perception that political leaders are failing to deliver. Despite the introduction of multi-party systems in many countries, the political space often remains tightly controlled by the regimes in power; free, fair and genuinely competitive elections are in short supply; and critical voices within the political opposition, media or civil society frequently face harassment, curtailment and control.

Protests are further driven by frictions caused by the arbitrariness of state rule and its often violent interference in the day-to-day lives of people – through the destruction of informal settlements, the dismantlement or relocation of informal markets, daily police harassment and extortion, for instance. This, in turn, impacts on already insecure and precarious economic situations. Recent protest movements in South Africa and Ethiopia offer an illustration of the close intertwining of these different protest dynamics.

Workers and students in the south

South Africa, a country with a long history of protests, has been most strongly affected by the increase in strikes and demonstrations over the past five years, driven by a spiralling economic crisis as the country confronts shrinking economic growth, a strong depreciation of the rand, and a 25% unemployment rate. Protests are also fuelled by popular discontent over the ruling African National Congress (ANC) party’s perceived failure to address the inequalities inherited from the apartheid era. This is particularly the case among poor and marginalised communities living in urban areas and informal settlements. Poor service delivery, urban housing, local government corruption, and forced evictions are the most common triggers of protests. These are generally localised and spontaneous, but they have the capacity to rapidly expand and escalate, and often involve the destruction of vehicles and state property. The mining sector, which accounts for about 7% of South Africa’s GDP, is also frequently marred by mass strike actions and unrest over wages, labour conditions, and slow progress in improving black ownership of mining assets.

Protests in South Africa are renowned for being often accompanied by violence. This is in part driven by the heavy-handed tactics employed by the police, which provoke retaliatory violence. The most notorious incident in recent years was the 2012 Marikana massacre, when the police – pressured by a platinum mining company (of which the country’s current Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa was a non-executive board member) and senior officials – opened fire on striking workers, killing 41 and injuring 78. But violence by protesters is also a reaction to what they perceive as ANC unresponsiveness to their grievances. Violence, and in particular destruction of public property, is seen as an effective means to force authorities to pay attention to their demands.

Riots and protests in Africa (1997-2014)

Over the past two years South Africa has also seen an escalation of student protests at universities, which have resulted in the disruption or suspension of academic activity at all major universities, violent confrontations between students and the police, and extensive damage to property. Students initially started protesting against higher student fees, concerned that this would prevent many already disenfranchised youths from accessing education, and the outsourcing of service jobs on campuses. But the movement has since expanded to also include calls for the ‘decolonisation’ of South African universities, as epitomised by the #RhodesMustFall campaign launched at the University of Cape Town in March 2015 to denounce institutional racism on campus. Universities are accused of having taken insufficient measures to increase the number of black students and faculty members and to revise curricula to ensure they include the works of African thinkers and secure a place for indigenous knowledge systems.

Although student protests have received the moral support of labour unions and churches, they have yet to link up with social movements beyond campuses, and it is unclear how sustainable the protests will be – also considering the loose organisation of the student movements. However, the protests feed into a broader backlash against the ANC, as illustrated by the growing influence of the Economic Freedom Fighters movement, the poor performance of the ANC in the August municipal elections in key urban constituencies, and the divisions within the trade union movement (an important traditional power base for the ANC). They reflect an increased questioning of the hegemony of the ANC over its failure to address economic disenfranchisement and redress racial and class inequalities.

Ethnic groups and regions in the east

When Ethiopia’s government announced its land reform measure, the ‘Greater Addis Ababa Master Plan’, in November 2015, regions inhabited by the Oromo and Amhara peoples – the two largest ethnic groups in the country – saw a sharp rise in street protests. The plan provided for an expansion of the capital of Addis Ababa into the surrounding Oromia region, a move which would cause the Oromo to lose their constitutionally-enshrined regional rights. Although the government abandoned its plan just two months later, the widespread opposition transformed a single-issue protest into a wider political campaign.

Although the protests began over a land reform measure, grievances run much deeper. They vary between regions and between political parties, but common factors are the opposition to the government, the call for a more democratic political space and a fairer distribution of wealth and jobs, and the fight against corruption. In sum, Ethiopia is confronted with the aspirations of a growing and increasingly well-educated youth that wants to participate in the political and economic system. In 2016, the protests in Oromia spread to the neighbouring Amhara region. While there are currently no indicators of a formal alliance, a political rapprochement between both groups would represent a significant threat to the government and an important shift in Ethiopia’s socio-political landscape.

The protests took a violent turn on both sides when protesters damaged foreign investments and government forces opened fire during the Oromo cultural festival last August in Bishoftu. The incident triggered the imposition of a state of emergency on 9 October for a period of six months, which included a curfew, detention without a court warrant, the monitoring of all communications, the deployment of federal security forces to the regions, and the prohibition of public gatherings. Since then, 11,000 people have been arrested – according to government sources – while Amnesty International estimates that around 1,000 have been killed in the protests since November 2015.

Internet access and social media activity have also been severely restricted. Several bloggers have been arrested and magazines have been pressured to stop publishing. The state of emergency effectively puts Ethiopia under military rule, and all constitutional rights are suspended. While it contained the protests in the short term, a political response is required to prevent a further escalation of the crisis. Political reforms were discussed at the Council meeting of the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) party in August, with an emphasis on the internal causes, political extremism and corruption. In October, the beginning of the parliamentary year, the president announced far-reaching reforms, including electoral reform, a more proportional system, a drive against corruption and the liberalisation of the economy. In November, Prime Minister Desalegn announced a cabinet reshuffle, which included the appointment of people with a more technocratic profile and the inclusion of nine new Oromo representatives. However, further concrete steps may be needed to address demands for job creation, fairer power-sharing, re-balancing the federal system between the centre and the regions, and more inclusive economic reforms.

Where next?

An important aspect of the recent protests is the central role played by youth movements such as Y’en a marre in Senegal, Balai citoyen in Burkina Faso and La Lucha in the DRC. They have been the harbinger of new forms of protest (different from more traditional civil society actions) and are rooted in the development of connections between grassroots activities and national-level protests. Social media has also played an important role in facilitating protests, in line with a wider trend of a growing popularity of hashtag campaigns. The #Tajamuka (‘We are fed up’) campaign in Zimbabwe, #Unemploymentmovement and #IShallNotForget campaigns in Botswana, or #Feesmustfall in South Africa illustrate how social media has enabled both a rapid and broad social mobilisation while also raising international visibility. However, due to the relatively low level of internet penetration in Africa compared to other regions of the world, the mobilising effect of social media continues to be mostly limited to urban areas, while street mobilisation remains reliant on more traditional methods such as leaflet distribution and word-of-mouth information spreading.

The prospects of the recent protests triggering political and socioeconomic change are challenged by the mostly repressive response deployed so far by governments. Excessive use of force by law enforcement actors against protesters, arbitrary detention, and harassment of protesters or their leaders are widespread. Governments also react by restricting freedom of movement, shutting down media outlets, and tightening legislation on non-governmental organisations’ (NGO) operations and funding. Data from Freedom House, a US-based NGO, clearly shows that there has been a general decline in civil liberties and political rights on the continent since the new wave of protests started – although this does not necessarily mean that such a decline is driven only by the protests. A willingness on the part of governments to engage in a dialogue and enact reforms to address the grievances has so far been limited.

Most protests in Africa are unlikely to result in regime change. While the successful removal of former presidents Abdoulaye Wade in Senegal and Blaise Compaoré in Burkina Faso raised hopes, the particular circumstances in both countries are not easily replicable. What is more, the Burundian experience shows that protests can also have the counter-productive effect of hardening a regime in power. And a key lesson to be drawn from the democratisation wave of the 1990s in Africa is that regime change does not necessarily lead to systemic change.

The current protests do, however, need to be taken seriously as evidence that more formal processes to affect change are not working, thus sending a strong signal to donors interested in supporting democratisation. Protests in Africa, therefore, should not necessarily be viewed as vehicles for regime change, even though this is the declared aim of some of them. Instead they are to be seen as a means to press for reform and challenge the state’s monopoly of political discourse and action.

About the Authors

Valerie Arnould is a Senior Associate Analyst, and Aleksandra Tor and Alice Vervaeke are Junior Analysts at the EUISS.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.