Constrained Leadership: Germany´s New Defense Policy

12 Dec 2016

By Daniel Keohane for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy (No. 201) was originally published in December 2016 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Germany’s new defense white paper says that it should contribute more to international security, including with military means. But will Germany substantially increase its international military role? And what impact will the election of Donald Trump in the US and the UK exit from the EU have on German defense policy?

The German government published a “White Paper on German security policy and the future of the Bundeswehr (German armed forces)” in July 2016, in between two political happenings with potentially major consequences for European security. The first event was the June decision of the British people to leave the EU. The second was the November election of Donald Trump to be the next president of the US.

The combination of these events has led some to suggest that Germany will not only become even more important within the EU, both to keep it from fragmenting further and to lead European foreign policies; but that Germany may also have to become the main defender of Western liberal values if the US scales back its commitment to defending the liberal world order under President Trump.

But would this extend as far as Germany playing a much greater military role in de-fending the liberal global order? The main message in the new white paper is that Germany should take on more responsibility for international security, and that Germany should therefore boost its military role on the world stage. This core message reflects am emerging trend: in recent years, Germany has become more active militarily, has promised to spend more on defense, and is cooperating more closely with allies.

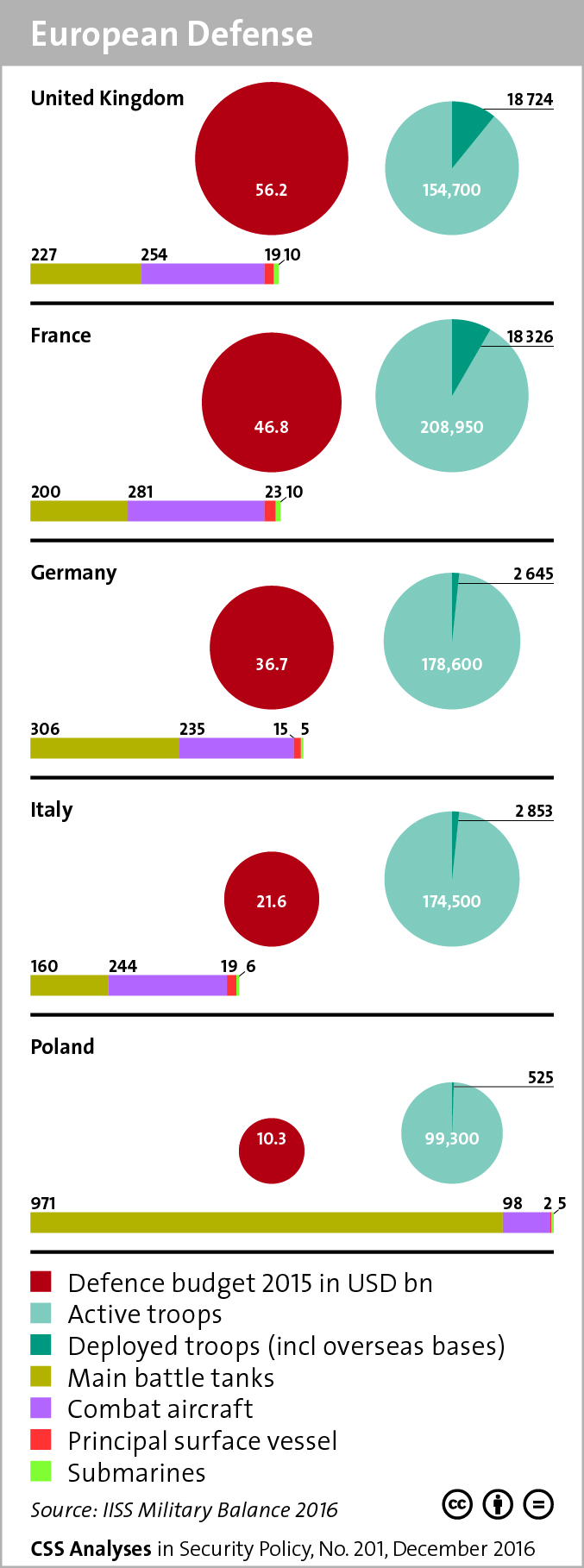

Most other Europeans and Americans welcome this upward trajectory of German military activity, as there is no doubt that NATO and the EU would benefit from a stronger German military contribution. After France and the UK, in absolute numbers, Germany is the third largest European defense spender in NATO. But expectations of German defense policy should not be too great, as Germany is doing more from a relatively low base compared to other allies of a similar size. German defense spending, for instance, only amounts to around 1.2 per cent of GDP, far below the NATO goal of 2 per cent (in comparison, France spends 1.8 per cent and the UK 2 per cent).

A Constrained Context

Germany has long had difficult debates about it military role in European and global security, going back to the landmark 1994 Constitutional Court decision that the German armed forces could be deployed beyond NATO territory within the framework of mutual security organizations, most importantly the EU, NATO, and the UN. That decision was followed by difficult debates over the Social Democrat/Green government’s support for NATO’s intervention in Kosovo in 1999.

Germany’s military contributions since then have fluctuated from strong support to the ISAF mission in Afghanistan during the 2000s to its abstention from the UN Security Council resolution preceding NATO’s military intervention in Libya in 2011. Germany’s non-participation in the 2011 NATO bombing campaign in Libya (and abstention from the UNSC vote) had a negative impact on Berlin’s relationship with its closest allies, and fed into an image of a country that was happy to let other Europeans shoulder the heavier military burdens. In early 2014, speeches by the German president, foreign minister, and defense minister all underlined that Germany should be prepared to take on more responsibility for international security, including with military means.

In response to the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014 – which shook many in Berlin – Germany not only led international diplomatic undertakings such as placing EU economic sanctions on Russia, but also pledged to reinforce air-policing capacities in the Baltic States, sent a vessel to the NATO naval task force in the Baltic Sea, and doubled its presence in NATO’s Multinational Corps Northeast headquarters in Szczecin, Poland. In addition, Berlin will lead one of four new NATO battalions soon to be stationed in Eastern Europe. All this is intended to demonstrate Germany’s firm commitment to NATO’s defense and to assure Eastern allies, as well as to deter Russia.

After the November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, Berlin moved quickly to get parliamentary approval to send reconnaissance aircraft and a frigate to support the intensified anti-ISIS bombing campaign in Syria. While this is not a full-blown combat role, it amounts to much more than Germany’s previous modest follow-on-support efforts to French combat operations in Mali and the Central African Republic during 2013 – 14. Since the 2015 Paris attacks, Germany has greatly enhanced its presence on the ground in Mali. Furthermore, Berlin sent weapons to a conflict zone for the first time to the Kurdish Peshmerga in Iraq and Patriot missiles to Turkey under NATO.

But the domestic legal and political constraints on using military force remain considerable in Germany. For one, the Federal Government has to have the agreement of parliament (the Bundestag) to deploy German forces abroad. For another, those forces can only be deployed with a sound international legal basis – until now, this meant preferably a UNSC resolution or at least within the framework of NATO and the EU. Moreover, domestic public opinion has generally been cautious about using military force. A series of Koerber Stiftung opinion polls from January 2015 to October 2016 shows an increase in the willing-ness of Germans to take a more active role in international crisis management (from 34 per cent to 41 per cent) – but although there is an increase in support for greater activism, a majority still prefer restraint (falling from 62 per cent to 53 per cent).

This constrained domestic political environment helps explain why the process for drafting the white paper was novel, in that a number of public consultations were held across the country to engage interested citizens. It also explains why the core idea in the white paper of German leadership on international security, including via military contributions, is new in the German political context.

Germany’s Strategic Outlook

The strategic analysis in the 2016 defense white paper takes a global outlook on international security, and starts with a sober assessment of Germany’s position in the world. In the long run, Germany is unlikely to remain the world’s fourth-largest economy, since economic power is shifting from the West to the East and South. Furthermore, the German economy is highly integrated into the global economy and depends to a large degree on continued globalization for its prosperity.

Germany has a keen interest in defending the current global system, by helping to deepen global governance and taking on more responsibility for global security. However, given its security interdependence with its EU partners and the US, Germany takes a “partnership-based” approach. As the white paper puts it: “Pursuing German interests therefore always means taking into account the interests of our allies and those of other friendly nations”. In that context, Germany intends to practice “leadership from the center” by assuming a leading role in coalition with its partners.

The values and interests outlined in the white paper are not new: values such as human rights, democracy, and the rule of law; alongside interests such as protecting German territory and citizens, upholding international law, and ensuring open global trade. What is new is the interest-based approach and tone of the document, which asserts that Germany is keener than before to promote its values and protect its interests. In other words, the white paper is not driven solely by an assessment of the security environment, but is also value-based and interest-guided.

The white paper states that Germany’s security environment is becoming ever more complex, volatile and unpredictable. Two geopolitical challenges in particular are highlighted. The first is Russia’s calling into question of the European peace order, as shown by its 2014 annexation of Crimea. The second is the fact that the EU is increasingly under pressure, as shown by the British decision in June 2016 to leave the Union. In addition, the white paper mentions a number of other transnational security challenges, such as international terrorism, cyber-security, fragile states, climate change, uncontrolled migration, and epidemics or pandemics.

Five strategic priorities are outlined in the white paper. They include two clear global security objectives: maintaining a rule-based international order and protecting the global commons (ensuring open trade routes and access to resources). Alongside those are three capacity-building aims, namely to ensure the German government can take a holistic approach to security (whole-of-government), develop its capacity to recognize crises early and prevent them, and contribute to strengthening the ability of NATO and the EU to act.

The central strategic importance of NATO for Germany is strongly emphasized in the white paper, which says that “only together with the United States can Europe effectively defend itself against the threats of the 21st century and guarantee a credible form of deterrence. NATO remains the anchor and main framework of action for German security and defense policy.”

The new German defense white paper also says that EU members should aim to create a “European Security and Defense Union” in the long-term. However, it is not entirely clear from the white paper what the implications of such an eventual European defense union would be in practice. For example, would it mean greater military integration under the control of national governments or ultimately via the Brussels-based EU institutions?

Operations and Military Capabilities

Germany will continue to participate in multilateral military operations, as it has long done through NATO, the EU, and the UN. What is new, however, is that Germany is now also prepared to act via ad hoc coalitions if necessary (such as that against ISIS). Moreover, the white paper says that Germany is not only prepared to participate in ad hoc cooperation; it may also consider initiating such coalitions.

This is a striking break with past German security and defense policies, which focused mainly on acting through multilateral institutions, and the de facto reality that Berlin has not been in the habit of initiating international military operations. While Germany has engaged in ad hoc diplomatic coalitions to deal with specific challenges such as Iran and Ukraine, whether or not Berlin will initiate ad hoc military coalitions in the future is an open question because of said domestic legal and political constraints.

The white paper states that the German government would like a more flexible interpretation of the law to be able to act if necessary, but ad hoc military coalitions might well turn out to be incompatible with Germany’s Basic Law (Grundgesetz), although the Constitutional Court has yet to be called upon to give a verdict. This raises the question of whether Germany can really lead without greater domestic political and legal flexibility.

The German armed forces, the Bundeswehr, are described as an instrument – one of several – of German security policy, rather than as a defense force first and foremost. The German white paper followed the publication of a new strategy document for EU foreign policy, the Global Strategy, in late June 2016. The comprehensive approach to international security outlined in the German white paper is similar to that described in the EU document, which envisages an “integrated” approach.

National and collective defense via NATO remains a core task, alongside external operations of varying types (ranging from training third-country armed forces to military interventions), and also some homeland security duties (the German constitution severely restricts this internal role). A key challenge for the Bundeswehr will be to develop the ability to cope with the entire spectrum of potential operational pressures. This in turn, as the white paper high-lights, will require the Bundeswehr to become a highly flexible and agile set of forces. A particular emphasis is therefore placed on developing better command-and-control and reconnaissance capacities.

Moreover, Berlin has pledged to increase its defense budget from € 34.3 billion to € 39.2 billion by 2020. However, although Germany is boosting its defense spending, a large number of capability gaps and shortages remain; addressing these adequately would likely require further defense spending hikes. The German defense ombudsman said in January that Germany has a shortage of usable military aircraft (amongst other capability types). For example, only 38 of its 114 Eurofighter jets were operational. German Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen has announced a plan to invest some € 130 billion in defense infrastructure and equipment by 2030, al-though those plans have yet to be fleshed out and approved.

In this capability context, European military cooperation – indeed, integration – is also important for Germany from a more practical viewpoint. Berlin has strongly pushed for more pooling and sharing of (mostly European) capability efforts, having proposed for instance the “Framework Nations Concept” for deeper capability development within NATO since 2013. Germany has acted upon its general desire for more European military integration by incorporating two Dutch brigades, one mechanized and one airmobile, into two German divisions, and by placing a German battalion under the command of a Polish brigade.

Brexit, Trump, and German Defense

Speaking while presenting the defense white paper on defense on 13 July 2016, von der Leyen said that Germany and France would lead talks with other EU members to assess their appetite for closer defense cooperation. She added that the UK had “paralyzed” progress on these issues in the past, but now the rest of the EU should move forward. Partly based on a number of subsequent practical Franco-German proposals, EU foreign and defense ministers approved a new plan for EU security and defense in mid-November.

While they agree on much, there are some major differences in strategic culture between Berlin and Paris, however. For one, France, as a nuclear-armed permanent member of the UN Security Council, has a special sense of responsibility for global security, and is prepared to act unilaterally if necessary. Germany, in contrast, will only act in coalition with others, and remains much more reluctant than France to deploy robust military force abroad.

Further Reading

John R. Deni, “external pageGermany Embraces Realpolitik Once Morecall_made”, in: War On The Rocks, 9 September 2016.

Bastian Giegerich, “external pageShare Guns and Sovereignty – Armaments Cooperation in Europecall_made”,, in: IISS Military Balance Blog, 26 August 2016.

Paul Hockenos, “external pageThe Dawn of Pax Germanicacall_made”, in: Foreign Policy, 14 November 2016.

Markus Kaim and Hilmar Linnenkamp, “external pageThe New White Paper 2016 – Promoting Greater Understanding of Security Policy?call_made”, in: SWP Comments, November 2016.

Stefani Weiss, “external pageGermany’s Security Policy: From Territorial Defense to Defending the Liberal World Order?call_made”, Bertelsmann Stiftung Newpolitik, October 2016.

Moreover, Berlin and Paris do not necessarily agree on the end goal of EU defense policy. Calls in the white paper for a “European Security and Defense Union” in the long-term give the impression that EU defense is primarily a political integration project for some in Berlin. The French are more interested in a stronger inter-governmental EU defense policy today than a symbolic integration project for the future, since Paris perceives acting militarily through the EU as an important option for those times the US does not want to intervene in crises in and around Europe. Because of their different strategic cultures, therefore, France and Germany may struggle to develop a more active EU defense policy more than their joint proposals would suggest.

The election of Donald Trump in the US will also put pressure on Germany to further increase its defense spending. In an interview with the Washington Post in March 2016, Trump singled out Germany for criticism about not pulling its weight within NATO. Furthermore, such views had already become main-stream in the US. In a 2015 Pew opinion poll, 54 per cent of US citizens said that Germany should make a greater military contribution to international security, with only 37 per cent saying it should limit its role.

However, although Chancellor Angela Merkel has said since Trump’s election that Germany will need to increase its defense spending, the defense budget may not grow substantially more in the short term, at least until after the 2017 general election, in part because of public opinion. In a 2016 Pew poll, only 34 per cent of Germans favored increasing defense spending, with some 47 per cent saying it should remain at its current level. Therefore, even though militarily Germany is doing more, spending more and cooperating more compared to before, the domestic political constraints on German defense policy remain considerable.

Germany’s new military ambition, as laid out in the 2016 defense white paper, along-side its recent growth in international military activity, should be welcomed by its partners. But a stronger German military role in international security will remain constrained by domestic politics.

About the Author

Daniel Keohane is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zürich. His CSS publications include “The Renationalization of European Defense Cooperation” (2016), and “Is Britain Back? The 2015 UK Defense Review” (2016).

Most recent CSS Analyses:

- Putin’s Next Steppe: Central Asia and Geopolitics No. 200

- Switzerland and Jihadist Foreign Fighters No. 199

- Bioweapons and Scientific Advances No. 198

- Brexit: Implications for the EU’s Energy and Climate Policy No. 197

- Swiss Border Guard and Police: Trained for an “Emergency”? No. 196

- One Belt, One Road: China’s Vision of “Connectivity” No. 195

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.