Defense Choices for the Next French President

17 Apr 2017

By Daniel Keohane for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy (No. 206) was originally published in February 2017 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

France has been the most militarily active European member of NATO in recent years, including a large domestic deployment because of an ongoing state of emergency. The next French President may have to make some major defense policy choices; on operations, spending, capabilities and international partnerships. Can France maintain its ambition to be a European power with global reach?

France is a permanent nuclear-armed member of the United Nations Security Council, with a special sense of responsibility for global security. The next president of France will wield tremendous power over French defense policy, including the ability, if necessary, to deploy force without immediate recourse to parliament. France has been the most militarily active European member of NATO in recent years, including a large domestic deployment because of an ongoing state of emergency.

The next French president will also inherit the second-largest defense budget among the European NATO states (over EUR 40 billion for 2017), which is planned to rise further, although future large increases may be constrained by the French government’s large budget deficit. The new French president may also produce a new white paper outlining the main geostrategic parameters for French defense policy for the following five years. All these developments come at a time when the security of France and Europe is threatened externally by Russia and internally by terrorism, among other challenges.

This analysis is not an assessment of the electoral programs produced by the French presidential candidates (the first round of elections will be held on 23 April 2017). Instead it considers the geostrategic and political landscape that will confront the next French president, alongside potential operational, budgetary, capability, and international partnership choices.

Geostrategic and Political Context

The main parameters of French defense policy were last set out in the White Paper on Defense and National Security of 2013, which outlined a considerable level of strategic and operational ambition relative to most other European governments, despite its announcement of cuts to national defense spending (from around 1.9 per cent to 1.76 per cent of GDP) and personnel (24,000).

After protecting national territory, guaranteeing European and North Atlantic security was considered the second strategic priority, but a threat from Russia was not discussed in the 2013 document. That has changed since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, and Paris has since responded to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine by sending an armored task force to Poland, increasing maritime patrols in the Baltic Sea, and cancelling the planned sale of Mistral amphibious assault ships to Russia.

Beyond Europe, French geostrategic priorities were narrowed in the 2013 white paper, prioritizing Africa (mainly North Africa and the Sahel) and the Middle East over the broader “arc of instability” – stretching across Africa, the Middle East, the Indian Ocean and Central Asia – highlighted in the 2008 version. The Indian Ocean was underlined as the next geostrategic priority, and the potential for strategic trouble in East and South-East Asia was also emphasized.

In other words, France has intended to remain a “European power with global reach”, continuing to strengthen military ties with a number of partners in the Gulf and the wider Indo-Pacific, even if it should prioritize security challenges in Europe and to Europe’s south. And France continues to maintain a global outlook on security. For example, despite the multitude of challenges to European security, French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian proposed in July 2016 that EU governments should send naval vessels to ensure open waterways in the disputed South China Sea.

Following the January and November 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris inspired by the Iraq/Syria-based ISIS, the geostrategic focus on the Middle East, North Africa, and the Sahel has been reinforced, alongside the need to deter Russia in Eastern Europe. The 2013 prioritization of territorial defense, European security, and the regions to the south of Europe, currently seems unlikely to change much – if anything, events since then have buttressed those priorities. But the hardening of the security environment for France and Europe has put added strain on the country’s defense resources (on which more in the next section).

Taking precedence over external priorities, since the November 2015 terrorist attacks, the French government has imposed a domestic state of emergency – whereby the executive and security services are granted special powers, such as searches without judicial oversight – which has been extended until 15 July 2017, a period that includes the upcoming presidential elections. This is the longest uninterrupted state of emergency in France since the Algerian war in the 1950s and 1960s.

And the war analogy does not stop there. French President Hollande and some of his ministers have described their struggle with Islamist terrorists (especially ISIS) as a “war”, language that most Europeans had previously associated more with neo-conservatives from former US president George W. Bush’s administration. Subsequent terrorist attacks, such as in Nice in July 2016, have stiffened the government’s war footing.

Some French security analysts (and a few politicians) have been very critical of this approach. As François Heisbourg from the Paris-based Foundation for Strategic Research (FRS) has said: “Bombing Raqqa and liberating Mosul are one thing; waging war on French citizens in St. Denis [...] is quite another”. A key decision for the next French president will be to decide on whether to prolong the current state of emergency – and to continue using such bellicose language – in part because of its impact on French defense policy.

Partly, but not only, because of the current threat from terrorism, there is widespread political support for increasing defense spending (currently, it equates to 1.8 per cent of GDP according to NATO figures) along with security funding (such as for police and intelligence forces). Three of the main presidential candidates, (François Fillon, Benoît Hamon and Emmanuel Macron) have committed to increasing the defense budget to at least 2 per cent of GDP, while another (Marine Le Pen) would like to raise it to an impressive 3 per cent (by contrast, the NATO-Europe average is just under 1.5 per cent). Few if any serious French politicians run on a political program to reduce defense spending and/or scrap France’s nuclear weapons program.

Operations, Budgets, and Capabilities

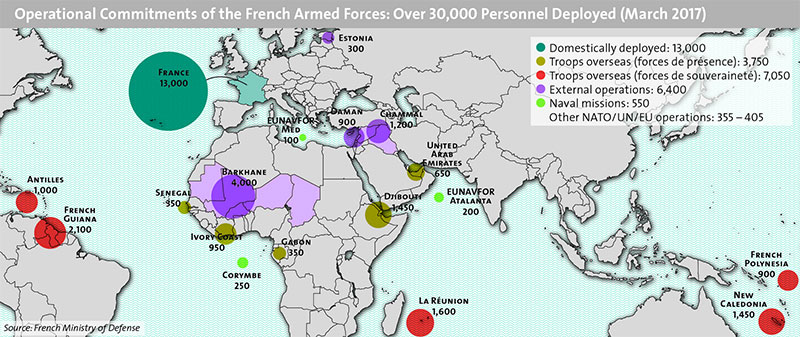

The domestic war footing against terrorists and the intensified bombing campaign against ISIS in Syria and Iraq have put added strain on French defense resources. For example, some 13,000 soldiers are currently deployed domestically to protect sensitive targets. Moreover, France is the EU member that has engaged in the most international military operations in recent years. In addition to intervening in Libya and Côte d’Ivoire in 2011, Mali in 2013, and the Central African Republic (CAR) in 2013 – 4, France has kept 4,000 soldiers stationed across the Sahel (stationed in Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Nigeria).

Paris also sent its aircraft carrier, the Charles de Gaulle, to the Persian Gulf to carry out strikes against ISIS in Syria and Iraq at the end of 2015. In a first for a non-US ship, the French carrier took command of US Naval Forces Central Command Task Force 50, which plans and conducts strike operations in the US Fifth Fleet area of operations. Furthermore, France is not neglecting its global outlook: Later this year, France will send a Mistral-class amphibious assault ship to the western Pacific for military drills with the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force, the UK’s Royal Navy, and the US Navy.

To some degree, these greatly increased domestic and international commitments have reduced France’s ability to defend NATO territory in Eastern Europe. However, it has previously sent fighter jets to the Baltic and ships to the Black Sea; although it is not one of the lead framework countries for NATO’s recently-deployed Baltic battalions, it is contributing 300 soldiers to the UK-led battalion in Estonia. Furthermore, France will take command of NATO’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force (VJTF) in 2020.

There is some debate in French military circles as to whether France can realistically keep up this tempo and combination of operational commitments, especially if they continue to grow. Some capabilities have experienced higher-than-planned attrition rates, for example. In July 2016, the government announced that it would create an 84,000-strong national guard for homeland security duties, drawn from the police, gendarmerie, and army reserve (which will also grow from 28,700 to 40,000 by 2018), to relieve the armed forces from their current domestic duties – a plan which the next president may wish to continue. In line with growing operational commitments, France also announced during 2015 (after the January Charlie Hebdo terrorist attacks in Paris) that the French defense budget would rise by EUR 3.9 billion between 2016 and 2019, resulting in a 4 per cent increase in real terms, and keeping French spending at around 1.8 per cent of GDP up to 2019.

To maintain France’s current level of strategic ambition, however, the French defense budget will have to increase further in the future. But even though the next French president will most likely want to continue increasing defense spending to at least 2 per cent of GDP by 2025, this may prove more difficult than presidential candidates may wish to admit. The French government budget deficit equated to around 3.5 per cent of GDP in 2016, well above the Eurozone average of 2.1 per cent in 2015. The French national auditor (Cour des Comptes) has consistently criticized the government for exaggerating its progress on improving the health of public finances. The European Commission in Brussels has warned that the next French president must immediately implement austerity measures to avoid breaching EU budget rules (the Eurozone’s agreed budget deficit limit is 3 per cent of GDP).

Since 2013, France has been spending its defense budget on developing a variety of force projection capabilities, with particular emphasis on intelligence-gathering and rapid response. The overall numbers of fighter jets, tanks, and (to a lesser degree) ships have been cut, but some of those capabilities are being replaced with more advanced models – and are being supplemented with more drones, satellites, transport planes, guided missiles, and special forces. Michael Shurkin of the RAND Corporation in the US says that the French military is highly conscious of its small size and lack of resources (compared to the US). He describes the French way of war as “substituting quality for quantity, and fighting smart, of making the most of the tools at hand”.

Despite a focus on terrorism, the French armed forces will remain committed to being able to cope with a full-spectrum set of security challenges, ranging from territorial defense to overseas deployments. For example, France will continue to maintain and upgrade its nuclear deterrent (which currently consumes around 11 per cent of the annual French defense budget, a proportion which is projected to rise in the future; the UK version, by contrast, consumes only 5 – 6 per cent of the yearly British defense budget, since it uses US technology). In a speech at Istres in February 2015, President Hollande warned of the risk of future strategic surprises, including a major state-based threat to France, requiring continued investment in the force de frappe.

The Charles de Gaulle aircraft carrier is currently being re-fitted, and some experts and politicians would like France to develop a second carrier to ensure that France always has this capability option. The idea of sharing a carrier with the UK was also mooted following the 2010 bilateral Anglo-French Lancaster House treaties, but this notion was later scrapped. However, a second French carrier would consume a significant portion of the defense budget. The UK’s two new aircraft carriers, for example, which will start entering service from 2020, will cost over EUR 3 billion each.

International Partnerships

After the UK leaves the EU (due by March 2019), France will be the leading military power in the EU by some distance. Since the Brexit vote in June 2016, France has made a number of concrete proposals together with Germany for strengthening EU military cooperation. Berlin and Paris have sensibly proposed that more of the costs of military logistics, medical assistance, and satellite reconnaissance should be shared, together with more EU funding for military research and equipment procurement.

They also wish to improve the EU’s ability to manage military operations and to deploy more quickly. And they would like a core group of countries to lead on EU military cooperation by deepening their mutual commitments via a legal mechanism in the EU treaties known as “permanent structured cooperation”. Moreover, France and Germany are deepening their bilateral cooperation. In October 2016, Berlin and Paris agreed to create a combined air transport squadron by 2021, jointly buying, basing, and using C-130 aircraft from the US.

Many French politicians pay lip service to deepening European military cooperation, but the next French president should not overestimate the potential for the Franco- German partnership to develop substantially stronger EU military policies. This is in large part because of their very different strategic cultures and visions for EU defense. The Franco-German Brigade, a joint military formation created in 1989, has rarely been deployed. The current German government strongly opposes French proposals to exclude some (if not all) defense spending from EU budget deficit calculations. Also, in contrast to many German politicians, no French president would call for a “European army” (with its federalist overtones). What more French would prefer is a strong Europe de la défense, meaning a full-blown intergovernmental EU military alliance – which France would lead.

Despite Brexit, the next French president should want to continue working closely with the UK on military matters. French strategic culture is much closer to that of Britain than that of Germany. One of the presidential candidates, Emmanuel Macron, said the day after the March 2017 terrorist attacks in London that while he supported a stronger EU defense policy, there was little chance of making it effective in the coming years. Macron added that France should pursue cooperation with both Germany and the UK. Based on the 2010 Lancaster House treaties, France and the UK are developing a combined expeditionary force and deepening their dependence on each other for missile technology, among other things.

Given the closeness of their military relationship, Defense Minister Le Drian has been at pains to stress that Anglo-French cooperation should be “Brexit-proof ”. But Franco-British military cooperation may not be immune to politics, especially difficult Brexit negotiations between London and Paris. There are precedents. According to Jean-Pierre Maulny of the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs (IRIS) in Paris, President Hollande downplayed the Anglo-French military partnership after his election in 2012 because of a political desire “to display the rebalancing of the relationship with Germany”, while the UK rejection of military action in Syria in 2013 put an end to the belief – enshrined in the 2010 treaties – that the French and the British would fight every battle together.

Another key relationship consideration for the next French president will be the potential impact of US President Donald Trump on Franco-US cooperation. The most supportive NATO ally of French military actions in recent years has been the US (which, for instance, has provided aerial refueling and troop transportation for France’s 2013 intervention and ongoing operation in Mali). Trump shares the French desire to defeat ISIS in Syria and Iraq, but his questioning of the future viability of both NATO and the EU may create both opportunities and challenges for France. The opportunity may be to reinforce France’s leading role on European defense as the strongest military power that is a member of both the EU and NATO. The challenge for an already-stretched France may be to shoulder an increased military burden if Trump were to scale back the US military commitment to European security.

The next French president will also likely wish to continue investing in other relationships beyond those with NATO and EU members. This is in part because France wishes to maintain a global military footprint, such as its base in Abu Dhabi, opened in 2009. It is also because the French defense industry has had an impressive run of export orders in recent years, reaching a record high of EUR 20 billion in 2016, and the next French president will want that to continue. Recent examples include fighter jet deals with India, Egypt, and Qatar, alongside a major submarine deal with Australia worth USD 37 billion over several decades.

All in all, the next French president should enjoy widespread political support for further increased defense spending, and for deploying robust military force if needed. But if France wishes to maintain its ambition to be a “European power with global reach”, the next president will still face some very challenging choices on operations, budgets, capabilities, and international relationships.

About the Author

Daniel Keohane is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zürich. His other CSS publications include Brexit and European Insecurity (2017), Constrained Leadership: Germany’s New Defense Policy (2016), The Renationalization of European Defense Cooperation (2016), Is Britain Back? The 2015 UK Defense Review (2016).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.