A Pedigree of Terror: The Myth of the Ba’athist Influence in the Islamic State Movement

7 Jul 2017

By Craig Whiteside for Terrorism Research Initiative (TRI)

Abstract

The presence of former members of Saddam Hussein’s regime in the Islamic State is well documented in hundreds of news reports and recently published books, and has become a staple in almost every serious analysis of the group. Attempts to measure the actual impact of this influence on the evolution of the group have left us with a wide diversity of views about the group; some believe it is a religiously inspired group of apocalyptic zealots, while others see it as a pragmatic power aggregator whose leaders learned to govern as the henchmen of Iraq’s former dictator. This article examines the impact that former Ba’athists made on who joined the Islamic State, how the organizational structure evolved, and the origins of its unique beliefs that inform strategy. The author relied on captured documents from multiple sources and Islamic State movement press releases collected since 2003 for this examination. The findings reveal that despite the prominence of some highly-visible former regime members in key positions after 2010, the organization was overwhelmingly influenced and shaped by veterans from the greater Salafi-jihadi movement who monopolized political, economic, religious, and media positions in the group and who decided on membership eligibility, structural growth, and strategic direction. This analysis should hopefully correct some inaccuracies about the origins and evolution of the group.

Introduction

The Islamic State claims in its propaganda to be a Salafi-jihadi group, a categorization that few serious terrorism analysts dispute, and therefore belongs to a community with a long heritage and very distinct membership amongst its different global strands, as documented by the likes of Kepel, Wiktorowicz, Hegghammer, and Hafez. During its inexorable rise to prominence, a handful of existing Salafi groups around the world pledged allegiance to the Islamic State, demonstrating that a plurality of jihadists took the legitimacy of the group seriously. Yet, jihadi rivals of the group frequently impugn this alleged credibility by pointing to the documented presence of former regime elements (FRE) from Saddam Hussein’s reign in the highest ranks of the Islamic State leadership. How should we understand this inherent contradiction, and what does it tell us about the group that has generated so much concern among nations around the world?

While competitors use the presence of the FRE in the Islamic State to delegitimize the group, analysts often use the same facts to explain a variety of aspects and events in Islamic State history. Critics of Wood’s depiction of the Islamic State as a religiously inspired group often use the Ba’ath angle to argue that the group leadership is more interested in a return to power than the Salafi-jihadi ideology. Others point toward the Islamic State’s fielding of effective conventional maneuver forces in 2013 as an example of the impact of Saddam’s former military officers, and the same goes for the highly developed Islamic State governance structures in 2014. Certainly, these analysts argue, the Islamic State’s security apparatus and emphasis on counterintelligence is an obvious product of an authoritarian regime that perpetrated extreme violence and genocide. These explanations are intuitive, based on real events involving real people, and convincing. And yet, the contradiction remains. How do the ideologues mix with their former persecutors in the Ba’ath, and how did they create such a high performing organization?

The purpose of this article is to answer this question in a more systematic way than previous explorations, and to make a serious effort to go beyond correlations and the use of the FRE as a heuristic for people to understand how the Islamic State rose to power. This article has three parts; the first looks at the people that made up the Islamic State, particularly the FRE, and examines their backgrounds and contributions to the movement since 2003. In the second, it traces the organizational influences on the evolution of the large bureaucracy that at one point was the world’s largest and wealthiest non-state armed group. Finally, in the third, it traces the FRE influence on the unique ideas pioneered and advocated by the Islamic State, concepts that have demonstrated remarkable longevity. The evidence–gleaned from Islamic State primary documents that were captured on the battlefield, as well as a database of Islamic State press releases–demonstrates that despite the presence of FRE in high levels of the organization after 2010, their influence has been fairly limited to specific areas. In contrast, long-standing members of the Salafi-jihadi movement from the region created this movement, nurtured it during its nadir, developed its unique and groundbreaking departments, and eventually midwifed the return of a modern caliphate.

If this is true, if the conventional wisdom that the former Ba’athists were the driving force behind the creation of the Islamic State is incorrect, then how and why does this matter? The importance of knowing your enemy is more than a pithy phrase; policymakers and advisors that make war on the Islamic State must understand the totality of its character in order to defeat it and achieve some lasting peace. Analysts who exaggerate the Ba’ath angle have contributed to a lack of understanding of the problem, with some consequence. One well-known Harvard scholar cited “the unlikely marriage of an extremist strand of Islam and some prominent former Ba’athist officials who knew how to run a police state” in his justification for a strategy of containment and the socialization of the proto-state into the international community. Fortunately, none of the main protagonists in the campaign to defeat the Islamic State chose to follow his advice, but the situation highlights why politicians must have access to an accurate depiction of threats to national security and global order. Furthermore, with this understanding, these same leaders can inform the public about the realistic duration of a struggle that will continue, at great length, into the unforeseeable future.

Background: ISIS as the Spawn of Saddam

It would be easier to find articles and books that do not mention the outsized influence of the FRE in the Islamic State, but for the sake of brevity I present three of the most influential works that contribute to this idea. Der Spiegel reporter Christoph Reuter wrote an article titled “The Terror Strategist: Secret Files Reveal the Structure of Islamic State” that is easily on pace to be the most cited article on this subject. In the piece, Reuter advanced an interpretation of the Islamic State based on his examination of one man’s personal documents that were captured in Syria in 2013. That same month (April 2015), veteran journalist Liz Sly wrote an article in The Washington Post that the editors titled: “The hidden hand behind the Islamic State militants? Saddam Hussein’s,” which traced the shadowy influence of mysterious Islamic State figures in Syria who were described as former Ba’athists. Finally, in a Wall Street Journal top ten book on terrorism, Michael Weiss and Hassan Hassan place a heavy emphasis on the role that Saddam’s intelligence men played in the resurgence of the group formerly known as al-Qaeda in Iraq. To summarize the collective and popular wisdom derived from these works, I quote Reuter:

IS has little in common with predecessors like al-Qaida aside from its jihadist label. There is essentially nothing religious in its actions, its strategic planning, its unscrupulous changing of alliances and its precisely implemented propaganda narratives. Faith, even in its most extreme form, is just one of many means to an end. Islamic State’s only constant maxim is the expansion of power at any price.

This conclusion, made by unbiased professionals and based on interviews with defectors and evidence collected on the battlefield, is completely understandable based on the glimpses of information we have on this clandestine and operational security savvy group.

In examining the veracity of this conventional wisdom, the best place to start is with the people that made up the Islamic State movement. As one observer remarked about the importance of people in his military organization, “Soldiers are not in the army. Soldiers are the army.” In examining the Islamic State movement and the extent that FRE were in its ranks, I tried to answer the following questions: how did former Ba’athists rise to prominence in an organization founded by veteran jihadists, including some who had suffered at the hands of the previous regime? What was the role of the FRE in the Islamic State movement prior to 2010? And finally, what influence did the much-touted Faith Campaign have on Iraqis in the decade of the 1990s, which allegedly “primed” some members of the former regime to adopt the harsh politico-religious ideology of Salafi-jihadism?

True Believers, Converts, and More

“Heed our warning carefully. Gone are the days of nationalism, patriotism, and Ba’athism.”

– Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, emir of the Islamic State of Iraq, 2010

In late 2001, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi led a small group of militants from the Levant region into the autonomous regions of Kurdistan in northeastern Iraq, men who formed the nucleus of the future Islamic State. The group’s leadership developed its own adaptation of the Salafi trend, with a focus on establishing a religious government in the near term that would facilitate the practice of what they termed the “prophetic methodology”–the best societal practices as derived from the accounts of the companions of the Prophet in the earliest days of Islam. Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the collapse of the authoritarian government under Saddam Hussein gave the early Islamic State founders room to operate and recruit within an expanded range. The Coalition Provisional Authority’s decision to disband the Iraqi Army broadened this recruiting pool even more by adding military veterans by the hundreds of thousands, including officers with membership in the ruling Ba’ath party. While seemingly thrust into an ideal situation, Zarqawi’s men nonetheless had to walk a careful tightrope; as ideologues who themselves had resisted five different requests to join Al Qaeda in Afghanistan, they were not prepared to admit ideologically suspect candidates into their future state project.

For the purposes of this article, former regime elements (FRE) are defined as people who were Ba’ath party members, such as officers in the Republican Guard and security organizations, or political operatives and workers within government departments. This definition excludes the rank and file military conscripts in the national army as well as low-ranking policemen, none of whom were required to be members of the Ba’ath Party. The leaders who sought out former Ba’athists were trying to attract the best and brightest from the Iraqi Sunni elite into the Salafi-jihadi group, in a very competitive environment made up of many rival Islamist and nationalist groups. Zarqawi’s early thoughts on the Ba’ath were made clear in his famous letter to Zawahiri, where he blamed the lack of enthusiasm of Iraqi Sunnis for jihad on Saddam himself. His impressions of the men who made up his recruiting base were of a race that had “lost their leader and wandered in the desert of artlessness and negligence divided and fragmented, having lost the unifying head… they are the result of a repressive regime that militarized the country, spread dismay, propagated fear and dread, and destroyed confidence among the people.” While Zarqawi earned a well-deserved reputation as an uneducated thug, his critique of the aftermath of Saddam’s reign rings true.

Despite these challenges, Zarqawi’s recruiters moved in many different circles to build the organization from a small cadre of experienced fighters to become the dominant insurgent organization in Iraq by 2006, according to one American intelligence estimate. One of the group’s early priorities was to recruit people with military experience. Abu Abdulrahman al-Bilawi was a former infantry officer who joined Zarqawi’s Tawhid wal Jihad in 2003 and was the only former regime member to make it into the leader’s inner circle, which primarily consisted of non-Iraqi jihadists. Captured in 2005, Bilawi spent eight years in jail before escaping in the large Abu Ghraib prison break in July 2013. His return to the movement, immediate appointment as a military emir for all operations in Iraq, and subsequent campaign to collapse the Iraqi security forces in several Northern and Western provinces in 2014 illustrates not only the wisdom of the early recruiting effort to secure military experience, but also the continuity of the movement and the current leadership’s respect for the “early adopters.”

Samir Abd Muhammad al-Khlifawi, more famously known as Haji Bakr, was a former officer in the Iraqi Army who joined the Islamic Army after 2003 and was captured in 2006. Due to his extensive profile in the Reuter article, Haji Bakr is often used by analysts as the archetype of the FRE in the group. A senior Iraqi Interior Ministry figure with access to his prison files indicated that a close associate of Abu Muhammad al-Lubnani–one of Zarqawi’s closest deputies–recruited him in Camp Bucca sometime between 2006 and 2008. Haji Bakr was then assigned as a security official in the Islamic State’s assassination squads, and he was elevated to the position of head of the military council in 2010 during the bloodletting that saw most of the top leadership killed or captured due to a security leak by the emir of Baghdad, Manaf al-Rawi. According to the Iraqi Minister, Haji Bakr was also responsible for the development of heavy weaponry for the Islamic State.

According to Reuter’s article featuring Haji Bakr, the former intelligence officer used his experience as part of a “tiny secret-service unit” attached to the anti-aircraft division to build the campaign plan for the subversion of Syrian rebel groups in 2012-13, and his personal papers revealed a series of sophisticated organizational charts and subversion plans. Based on these papers, Reuter described him in the article as “the architect of the Islamic State.” However, this is a very premature conclusion. First, it is possible that Haji Bakr’s background as a military intelligence officer did not correlate at all to counter-intelligence activities (they are distinct fields), and the same Iraqi official made no mention of any special mukharabat background when describing him as a former “Staff Colonel.” Second, there is no proof that these subversion tactics and plans were not standard doctrine for the group before the Iraqi insurgents moved into Syria–men who, after all, had been fighting for much of the past decade against a very capable military.

One of the most thorough (and balanced) examinations of the FRE in the Islamic State to date is Truls Tønnessen’s examination of jihadi biographies in Perspectives on Terrorism, which concluded that while al-Qaeda-trained veterans founded the Islamic State movement in Iraq, a coterie of former Iraqi officers served as successive heads of its military council since 2010, including Haji Bakr and al-Bilawi (mentioned above), Abu Ayman al-Iraqi (a.k.a. Abu Mohannad al-Sweidawi), and Abu Muslim al-Turkmani (a.k.a. Haji Mutazz). Analysts have used these series of appointments, which occurred during the campaign to secure a more permanent state structure for the movement, as an indication of the importance of the FRE to the Islamic State. However, there is a tendency among these writers to exaggerate and assume a much wider infiltration of the movement by FRE. This is compounded by actors like the Iraqi government–which fears a mythical Ba’athist resurgence–and jihadi rivals that actively promote misinformation campaigns that together have contaminated much of the writings on this topic. Even Tønnensen’s analysis included some of these rumors (with qualifications), misidentifying Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, Abu Maysara al-Iraqi, and Abu Ali al-Anbari as former regime members. These errors did not influence his overall conclusion, however; Tønnensen recognized that despite the presence of Haji Bakr et al., “it is still difficult to argue that [the Islamic State] is the ‘Ba’ath party resurgent.’”

Ironically, despite the sensitivities of having FRE in the ranks, the leadership made no attempt to hide this recruiting priority. Zarqawi, his successor Abu Omar al Baghdadi, and Baghdadi’s military deputy Abu Hamza al Muhajir made public statements on the need to recruit members of the former regime for their military experience. In fact, the Islamic State’s attitude toward recruiting former Ba’athists differs greatly from its harsh treatment of fellow Islamists–particularly the Iraqi Islamic Party (Muslim Brotherhood), whose members were treated as dangerous rivals and targeted for assassination. In a 2008 speech to the Iraqi people, Abu Omar eulogized the field commander of the Islamic State of Iraq, Abul-Basha’ir al-Juburi (a former colonel in Saddam’s army), and called him one of the state’s top martyrs. He invited other former regime members to repent, repudiate the Ba’ath, memorize part of the Koran, and then join the Islamic State. In an al Furqan media interview during this period, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir also referred to al-Juburi when he deflected complaints against the Islamic State’s practice of killing rival Sunnis, bragging that more former regime officers had joined the Islamic State movement than any other in Iraq. This was undoubtedly a lie; there were numerous other popular resistance groups that had an overwhelming presence of Ba’athists that far outnumbered the Islamic State at the time, such as the 1920s Revolution Brigade, the Islamic Army of Iraq, and Jaysh al-Mujahideen. Nonetheless, as these two public interactions confirm, both leaders made repeated and open efforts to recruit religiously vetted FRE in the years after Zarqawi’s death.

One mistake that analysts often make regarding the Ba’ath influence, is assuming that Sunnis were monolithically supportive of the regime or that service in the large governmental and security structures equated to a genuine allegiance to the dictator. One such individual who struggled with this reality was Abu Omar al-Baghdadi (Hamid Dawud Mohamed Khalil al-Zawi), a former local policeman in Haditha dismissed from the force during the late 1980s/early 1990s for his outspoken Salafi attitude. His Islamic State biographer excused his service as a policeman in the services of an apostate government, acknowledging that at the time, the Salafi trend did not consider this to be a disqualifying action. As proof of Abu Omar’s bona fides, the author related a story about the future emir. When coalition forces detained Abu Omar for suspicion of being a Zarqawi supporter in 2004 (he was), his American captors questioned him about a document on his computer denouncing Saddam Hussein, including a detailed listing of Saddam’s one hundred- plus acts of apostasy. According to his biographer, Abu Omar reminded his captors that they had the same opinion of Saddam as he did, and he was later released. He went on to become the first emir of the newly established Islamic State of Iraq in 2006.

The virtual promotion of Abu Omar as a former police or army general at least had some kernel of truth–his past as a local policeman–compared to the case of Abu Ali al-Anbari. Abudulrahman Mustafa al-Qaduli (also known as Anbari, Haji Iman, Abu Ala’a al-Afri) was the former Islamic State head of Sharia and religious policing (hisba) in Syria, and later the manager of state finances before his death in 2016 at the hands of U.S. special operations forces. Analysts, reporters, and policymakers repeatedly called him the “ex-Ba’athist general,” using his Ba’athist past as the epitome of the former regime’s infiltration of the Islamic State. In their influential and authoritative book on the movement, Weiss and Hassan described the amni (security unit) as “developed by former Iraqi Mukhabarat officers in its ranks. The entire spy sector of ISIS is headed by Abu Ali al-Anbari, the former operative in Saddam’s regime.” This mistaken attribution of Anbari as a former Saddamist general spawned literally hundreds of citations that were repeated in top journals, newspaper articles, books and blogs. The fact that the origins of the story came from defectors from the Islamic State and rivals should have given these analysts pause. To their credit, Weiss and Hassan are the only writers to correct the record about Anbari in their article titled: “Everything That We Know about this ISIS Mastermind was Wrong.”

Following Anbari’s death, we finally learned the truth: he was a career Salafist who had been a member of Ansar al-Islam in 2003 before joining al-Qaeda in Iraq, and was esteemed enough to be elected the head of the Mujahideen Shura Council in 2006–the political front that preceded the establishment of the Islamic State. Detained by British special forces that April, he was able to shield his identity as a top political leader and was later released by the Iraqi government in an early 2012 amnesty. He immediately returned to the Islamic State organization and participated in its phoenix-like rise, playing a large role in its expansion from Iraq into Syria in 2013 by recruiting many independent jihadist groups. He also advised Abu Bakr on relations with their errant affiliate–Nusra Front.

The irony of this confused identity is heavy; despite the capture of detailed Ba’athist records in 2003, no one was ever able or willing to verify that the alleged head of the Islamic State’s intelligence unit was not an ex-Ba’athist general trained by the KGB, but instead a veteran Salafi-jihadi (from the 1980s) whose experience was largely in supervising regional sharia functions for then al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) and more recently the Islamic State. Anbari’s post-prison religious lecture tapes are considered to be the definitive promulgation of the Islamic State’s religious doctrine. Furthermore, it is conceivable–based on the Islamic State’s detailed eulogy of Anbari in its al Naba newspaper–that he had no intelligence responsibilities and that these descriptions were tied to the mistaken assumption that he was a former Ba’ath general.

If the confusion over Anbari stems from rumors that became legend, two other accounts that push the Ba’ath hijacking of a weakened Islamic State movement around 2010 are obvious rival information operations campaigns that should be relied on with extreme caution. “Abu Ahmad” claimed to be reporting the experience of a Zarqawi-era defector in one celebrated report, and “wikibaghdady” in a similar account reported intimate details about the group’s efforts in Syria to coopt various armed groups fighting the Assad regime. Both authors claim that the members of the cabal surrounding Abu Bakr - especially Haji Bakr - were agents of a Ba’ath resurgence in Iraq, and close associates of the Bashar Assad’s regime in Syria. While both accounts have verifiable details, they are also riddled with errors. For example, “Abu Ahmad” was wrong about Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s imprisonment in Bucca, putting it two years after it happened; he claims that the leader of the MSC, Abu Abdallah al-Baghdadi, was really Abu Omar (instead of Abu Ali al-Anbari); and he makes sure to gratuitously dispute Abu Bakr’s Qureshi lineage. Both authors’ proposal that Abu Bakr came out of nowhere to lead the group (with the assistance of the Ba’athists), instead of being carefully groomed for years by the existing leadership, is contradicted by many accounts. These issues and their general conspiratorial nature should give us pause about the true background and intentions of these authors.

The misinformation campaign about the Ba’ath influence in the Islamic State, deliberate or not, does not restrict itself to verified veterans of the Islamic State movement. The Izzat Ibrahim al-Douri saga has been the most egregious example of misinformation, with numerous reputable news sources reporting that Douri’s Naqshbandi group (known by its Arabic acronym JRTN)–the official neo-Ba’athist movement in Iraq–had pledged allegiance to the Islamic State in 2014. The official press offices of the Islamic State and JRTN both denied these reports, which had been breathlessly reported as evidence of the convergence of the two movements. Subsequent JRTN critiques of Islamic State governance, massacres of the Shia cadets at Camp Speicher, and the periodic roundup and execution of senior former regime officers in Mosul have demonstrated that JRTN and the Islamic State do not see eye-to-eye. Despite numerous predictions that JRTN would be the next Sunni insurgency following the withdrawal of U.S. forces, when the Salafis in the Islamic State returned in 2014 from defeat they met the Sufis of JRTN–led by a true Ba’athist general–who then wisely and rapidly disappeared from public view.

The Islamic State’s release of biographies and eulogies in the past several years has made it clear that the recent leadership of the Islamic State, particularly politico-religious leaders like Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Abu Ali al-Anbari, and Abu Mohammad al-Adnani, have come from the pre-2003 underground Salafi movements of Iraq and Syria. Their collective embrace of a select cross-section of former regime officials is a strong argument for considering the impact of the religiously infused ideology of Salafism as the magnetic element that brought this “unlikely” group together, to echo a quote cited above.

To explain this religious trend among the FRE, some analysts have put forth the theory that Saddam’s Faith Campaign had primed Iraqi society and set the stage for the rising popularity of Islamist movements. In this explanation, it is unclear as to whether Saddam was deliberately manipulating the growing religiosity of the population or if he was truly undergoing a similar conversion to more conservative religious views. In a New York Times piece, Kyle Orton described how the influence of Saddam’s regime was the cause of a growing Salafi movement, which by this time supposedly netted Saddam’s intelligence agents who, while spying on the underground movement, were themselves converted. No researcher has rigorously tested aspects of this theory, but nonetheless it has been prominently offered as an intuitive explanation for why certain members of Saddam’s regime went on to join and fight for the Islamic State.

Brill and Helfont strongly dispute this explanation of an Iraqi society transformed by an Islamist leaning Saddam Hussein, and their examination of captured documents housed at the Hoover Institution’s Ba’ath archives found no evidence of any Salafi transformation of Saddam’s inner circle or the society at large. Citing Saddam’s speeches attacking Islamists as the “two-faced men of religion,” Brill and Helfont convincingly dispute any attempt to link Saddam to the Islamic State. Instead, they conclude that the destruction of the Iraqi state in 2003, the sectarian struggles of 2004-2007, and the “authoritarian aspirations” of the Shia-dominated Maliki regime were much more important factors in the rise of the Islamic State.

To conclude this section, the Islamic State’s leaders deliberately recruited capable (and religiously acceptable) individuals with military experience from 2003-2006 when they had a shortfall in this particular skill. These people were Salafi first, former military officers second, and then former Ba’athists in identity salience. As the organization matured and its members gained combat experience, there was less of a need to recruit for this skill. In fact, the leaders of 2014 were established and credible members of the old guard–regardless of their original background.

Structure as Destiny

You [the U.S.] were [sitting] safely in your country receiving the riches of Iraq, and you had imposed on us a rabid ruler who stole our money and killed our men and fought our religion, and we were ever so eager to fight you directly so that we can [take our revenge] from you, for we knew that you were the serpent’s head and evil emanates from you. But the tradition of betrayal mandated that you would turn your backs to your agent [Saddam] and suddenly hate him, so you cut off his neck and you sent him to the Avenging and Overpowering King [Allah], and we got what we never expected or contemplated, to see your soldiers in front of us and on our soil in an act of injustice on your part, and in our yearning for your blood.

– Abu Omar al Baghdadi (2008)

This next section will assess the influence of the former Ba’ath regime members on the emergent hierarchy of the Islamic State movement. Existing as an amorphous network in its early years in Iraq (2002-2005), emir Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and the shura (consultative) council transformed the movement over several years into a multi-layered bureaucracy. Despite the security risks of building a highly structured organization subject to enemy targeting, the leadership of the movement used the transition from Al-Qaeda in Iraq to the Islamic State of Iraq to build a national level structure that would perform three important tasks: control its members’ use of violence, maximize the value of group resources, and expand territorial control into new areas. The vehicle the leadership chose was the “M-Form” type of organizational structure, which has a centralized set of departments that are replicated at multiple localities.

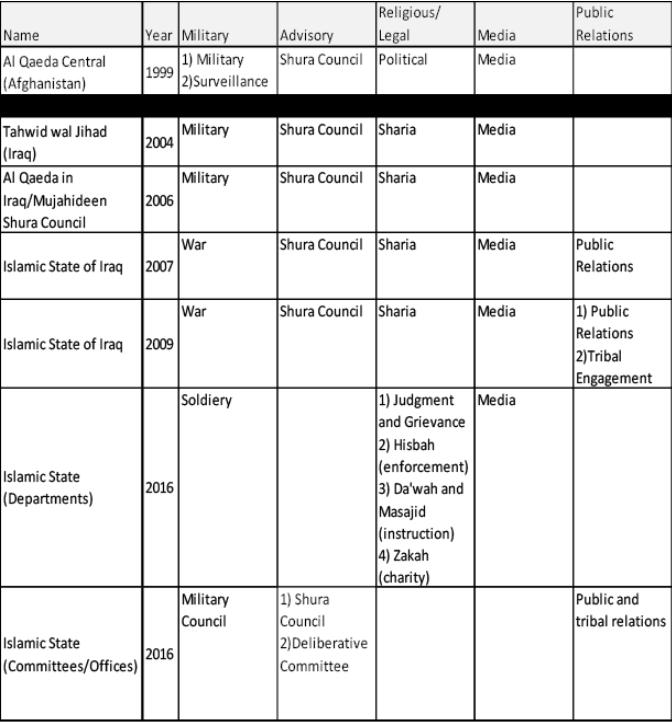

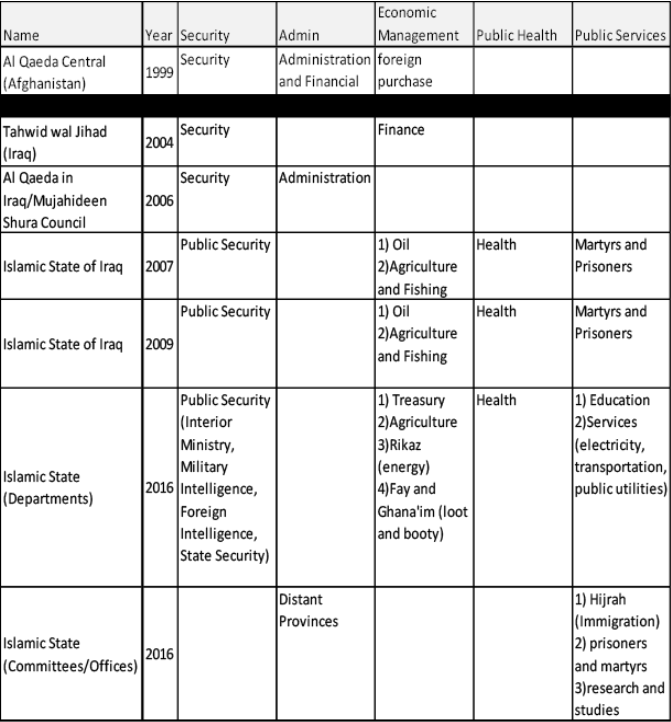

It was the veteran jihadists–most with experience gained in al-Qaeda’s camps in Afghanistan before 2001–that put together the blueprint for the future Islamic State. Accordingly, there should be no surprise that the original frameworks of Tawhid wal Jihad, al-Qaeda in Iraq, the Mujahideen Shura Council, and the Islamic State of Iraq are all closely derived from that of Al-Qaeda Central, if not identical. According to captured documents available from the Harmony Collection at West Point, Al-Qaeda’s organizational chart in 1999 included the following departments: military, political (sharia), information, security, surveillance, foreign purchase, and an administrative and financial committee (see first line of Figure 1 below, “Al-Qaeda Central.”)

In comparison, according to captured Islamic State of Iraq documents, the group’s provincial governance in Anbar province had similar subunits by late 2006: military, legal (sharia), media, security, and administration (see Figure 1 below.) Missing a foreign purchase division, the leaders instead relied on elements of its administrative wing to conduct financing and run its lucrative extortion efforts that served to free the leadership from outside influences and fundraising activities–a key imperative learned from Abu Musab al-Suri’s lessons from the original Syrian uprising. Anbar province’s organization mirrored a similar structure at the national level, with the exception of a shura committee. Captured documents confirmed that lower level district organization in the towns of Tuzliyah and Julayba in Anbar were organized exactly like their provincial parent. To show the extent of the sophistication of the organizational structure in this early period–in light of Reuter’s surprise at the incredible detail of Haji Bakr’s wire diagrams in 2013–the Anbar provincial administrative emir in 2006-7 supervised a unit responsible for economic studies, loots and sales, aid and storage, human resources, inventory and audit, movement and maintenance, finance and accounting, and programs improvement and training.

The announcement of the first “cabinet” of the Islamic State in April 2007 demonstrated the beginnings of an evolution that built on the al-Qaeda Central-influenced structure, with the following ministers: a deputy to the emir/war minister (long-time Zarqawi deputy Abu Hamza al-Muhajir), public relations, public security, media, oil, Sharia, martyrs and prisoners, agriculture and fishing, and health. A second slate in 2009 produced a new list of ministers of the same departments. Aymenn al-Tamimi noted that many of the titles (professor, doctor, engineer) of the individuals named in both slates give the impression of technocratic expertise, while also maintaining an impressive inclusion of diverse and important Sunni tribes (Janabi, Mashadani, Dulaymi, Jubouri) with a minimum of foreigners.

In 2009, in reaction to its routing by pro-government Sunni militias (Sahwa) and other counterinsurgent forces two years earlier, emir Abu Omar al-Baghdadi created a tribal engagement office that financed and managed local efforts to recruit and co-opt Sunni tribal figures back into the Islamic State fold. Along with this political outreach, security detachments (like the one Haji Bakr was assigned to run) assassinated key Sahwa figures that refused to renounce their affiliation with the government or were fingered by tribal rivals as impediments to the destruction of the local Sahwa organization. The survival of the tribal engagement office in the current structure of the Islamic State is vindication of both the importance and the effectiveness of this structural innovation. While Saddam had also flirted with tribal engagement during times of regime stress with limited results, the creation of this department by Abu Omar al-Baghdadi–an original member of the Iraqi Salafi movement–played a large part in ensuring access to the Sunni population and securing a comeback in later years.

The Islamic State’s current structure (2016-2017) contains the same original departments of the early movement and many new ones, now that the organization governs territory and tends to the needs of a real population. According to a detailed media release about the current structure, the “delegated committee” advises caliph Ibrahim (Abu Bakr) and supervises 35 provinces (wilayet), nineteen of which are in Iraq/Syria. There are 14 departments: Judgment and Grievance, Hisbah (religious enforcement), Da’wah and Masajid (religious instruction), Zakah (charity), Soldiery (military), Public Security (internal), Treasury, Media, Education, Health, Agriculture, Rikaz (energy resources), Fay and Ghana’im (loot and booty), and Services (electricity, transportation, public utilities). These bodies are supported by the following committees and offices: Hijrah (immigrants), prisoners and martyrs’ family welfare; research and studies, distant provinces, and public and tribal relations (see Figure 1 below). Each province is led by a governor (wali), who supervises a comparable structure, albeit when properly resourced with personnel and funds. From modest beginnings in 2006, the Islamic State evolved from a copy of the al-Qaeda organization to its own unique and sophisticated structure based on its experiments in governance and interactions with the local population. With the possible exception of the internal subdivisions of the amniyat (security) department, none of this reflects the influence of the former Ba’ath regime.

Figure 1: Structural Evolution of the Islamic State Infrastructure (2003-2016)

Competing Influences: Salafi Evolution or Sons of Saddam?

The third and final area of this article relates to this author’s findings on the impact of the former Ba’athists on the ideas and practices of the Islamic State. The proponents of the idea of a strong Ba’ath influence on the group point toward the group’s dramatic military success, excessive and telegraphed brutality, and the sophistication of its intelligence operations as evidence. To date, this analysis has largely been more intuitive and based on interviews of defectors, than on empirical evidence or an appreciation of the history of the organization. To test for Ba’athist influence, this section examines three important practices that have set the Islamic State apart from other insurgent groups: belief in the efficacy of violence, utilization of sectarian wedges, and its unique counterintelligence practices.

The Islamic State’s embrace of violence as a multi-use tool serves many goals, and its irregular warfare campaign strays far from the usual rhetoric of insurgent groups trying to win the hearts and minds of the population for the eventual overthrow of an incumbent government. Some authors ascribe this predilection for public violence to the Ba’ath members within the Islamic State. The problem with this narrative can be explained with one name: Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. As the charismatic founder of the movement, Zarqawi set the lasting norms for the group’s unique and enduring doctrine of using violence as an effective political tool. While Jihadi scholars often ascribe the origins of this method to the influence of the 2004 jihadi publication Management of Savagery, the Islamic State rejected that notion and claimed that, while similar, Zarqawi’s campaign plans and overarching strategy–often described in its releases as an embrace of al wala’ wal bara’ (loyalty and disavowal)–were completely original and approved by the group’s shura council before Management of Savagery was ever published.

Certainly, the group’s first strikes in 2003 against the United Nations, the Jordanian Embassy, and a Shia procession at the Imam Ali mosque in Najaf were an early proof of concept that violence could tear the new Iraq apart. Within weeks of announcing the “official” formation of his group in early 2004, Zarqawi’s media department filmed his participation in live decapitation videos posted for worldwide consumption on the Internet. These same media teams followed suicide bombers into markets to capture raw footage of Shia civilian victims in order to peddle them in videos to Sunnis angry about ethnic cleansing by government allied forces. Zarqawi created assassination brigades as early as 2004 to strike back at government targets, Shia militias, and even Sunni rivals in a brutal and devastating irregular warfare campaign. By the time of his death in 2006, Zarqawi had formed well-established norms of organizationally directed violence, including mass executions of Iraqi policemen and targeting civilians for weekly mass bombings, that long outlasted his reign as the leader of the movement. As a sign of this continuity, Zarqawi’s Iraqi successors (Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi) both continued these violent practices for over a decade.

In addition to a belief in the efficacy of violence as a strategic tool to shape public perception and terrorize his foes, Zarqawi’s controversial and steady advocacy of a sectarian strategy survived well into the current period. Not surprisingly, this enduring trait of the Islamic State is rarely mentioned in discussions of the role of the former regime members in the group. While the Ba’athist regime professed to be secular in nature, and included Iraqis of all sects and ethnicities, the Islamic State’s peculiar version of Salafism has predisposed its leaders to view the Shia of Iraq as deviants from the proper path and a historic threat to Sunni leadership of Iraq. Zarqawi argued early on that the Shia were the main threat to the establishment of a caliphate in Iraq, and used sectarian attacks as a wedge to push more moderate Sunnis into his camp. Sectarianism was not a result of civil war, despite Zarqawi’s crocodile tears in 2005; Zarqawi’s slaughter of hundreds of Shia pilgrims in March 2004 reinforced that this was a calculated strategy that continues to this day–as seen in the annual targeting of the Ashura and Arba’een festivals or in the infamous Camp Speicher massacre.

Despite the controversy over his targeting of Shia civilians, one reason Zarqawi expanded his group so quickly in the early years was his recruiters’ focus on the underground Salafi community that existed in Iraq for decades. This community, often viewed by Saddam with extreme suspicion, had ironically benefited from the tentative relaxation of secular practices during Saddam’s Faith Campaign. Often incorrectly described as products of the Faith Campaign, they were instead earlier converts to a more genuine and regionally dispersed campaign waged in mosques by speaking tours of members of the international Salafi movement, similar to those of Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani. While Zarqawi is on public record as bemoaning the state of the Iraqi Sunnis in his famous letter to Zawahiri, he had to have been pleasantly surprised by the existence of such a robust underground community.

An interesting characteristic of this Iraqi Salafi community was its virulently anti-Shia nature, something that most likely existed for decades, if not centuries. While Zarqawi had been a recent adopter of anti-Shiism based on his observations of Shia collaboration with the American invasion of both Afghanistan and Iraq, the members of the Iraqi Salafi milieu–including Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and Abu Ali al-Anbari–all viewed the Shia community as a legitimate target in their efforts to reclaim Iraq and probably held these beliefs long before Zarqawi’s arrival. This relatively extreme belief–not particularly shared among the leadership of mainstream Sunni insurgent groups–was a contributing factor to the violent divisions that eventually inspired the Awakening (Sahwa) movement in Iraq in 2006, an event with significant consequences for the Islamic State movement.

Matthew Barber’s short history of one Iraqi family of the Salafi movement, the Badris, illustrates how anti-Shiism was not a foreign import but a long-standing trend among Iraqi Salafis, particularly in a highly mixed-sect and religiously important area like Samara, the capital of Salahuddin province. Subhi al-Samerai al-Badri was a career police officer who had to curtail his anti-Shia attitudes when the secular Ba’ath consolidated power in Iraq in the 1970s, and went to Saudi Arabia to preach instead. He later returned to Iraq and was known by students for his extended sectarian rants during class, despite the Ba’ath party’s restrictions on such speech. Several biographers of early and influential Islamic State members named the esteemed Subhi al-Badri (d. 2013) as the religious teacher of their subject. Even more indicative of the importance of this social network to the leaders of the Islamic State is the fact that al-Badri was related to the current “caliph” Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, whose real name is Ibrahim Awad Ibrahim al-Badri. Despite the stringent efforts of the Saddam regime to sabotage any and all threats to its power, the underground Salafi movement grew in influence and membership in Iraq during the late 1980s and 1990s, and was dedicated to replacing Saddam with a more acceptable religious government. Abu Ali al-Anbari’s two part eulogy in the Islamic State media mentions a similar beginning for this movement veteran; Anbari studied under a Sheikh Fayiz in the 1980s, joined the Salafi group Ansar al-Islam around the time of the 2003 invasion, and defected with several others–including future media emir Khaled al-Mashadani and former special forces officer Abu Muslim al-Turkmani–to Zarqawi’s group around 2004-2005. His original teacher, Fayiz Abdul Rahman al Zaidi, was a Salafi preacher in Mosul during the 1970s and had been imprisoned by the Saddam regime on several occasions before being executed with two other individuals, allegedly for trying to convert Shia to Salafism and for declaring military service under the Ba’ath to be “humiliating.” One researcher noted that these acts of defiance were a result of “the role played by Saudi Arabia in promoting Salafi thought by flooding Iraq with Salafi literature during the rapprochement between Baghdad and Riyadh because of the Iraq-Iran war in the 1980s. At a time when many religious books, Sunni and Shi‘a alike, were banned in Iraq, government censors turned a blind eye to the distribution and sale of Salafi books from Saudi Arabia. But despite its ostensible toleration of the spread of Salafi ideas and literature, the Ba‘ath regime did not hesitate on a number of occasions to resort to brutal methods to remind the Salafis of who was really in charge.”

These intriguing threads reveal the difficulty of trying to simplify the complex backdrop from which the Islamic State rose. The group’s first spokesman, Abu Maysara al-Iraqi (from Kazimiyah, Baghdad), was a convert from Shiism who led his family into the Salafi practice. In the process he was jailed by the regime before being released in 2003. Sam Helfont argues that it was this systematic neutralization of Salafis, Wahhabis, and Islamists (including the Iraqi Islamic Party/Muslim Brotherhood) in the decades before 2003 that paved the way for a Faith campaign that was just another method of coercion and control of the population.

Beyond violence and sectarianism, the final analysis of FRE influence on unique aspects of the Islamic State’s beliefs and practices focuses on the group’s excellence at counterintelligence–something widely attributed to Saddam’s former agents. This argument, advanced with persistence and sophistication by prominent Islamic State analysts, points to the skill with which the group conducts intelligence operations outside of its controlled territory and counter-intelligence inside the “caliphate.” This focus on the amniyat (security) department and its presumed origin relies on the assumption that jihadist groups do not naturally practice counter-intelligence, a skill which apparently is naturally limited to the government officials of authoritarian states. Once again, like many of the ideas that make up the shibboleth that Saddam was the godfather of the Islamic State, this is a reasonable proposition that weakens in explanatory value with a minimum of effort.

Clandestine movements like al-Qaeda absolutely require counter-intelligence functions in order to operate in authoritarian countries. Abu Musab al-Suri’s experience in the Syrian rebellion against Hafez Assad emphatically pointed to the absence of this skill as a major reason for the infiltration and subsequent collapse of what should have been a great opportunity for the Islamists and Salafi groups that populated the resistance. Al-Qaeda’s experience in Afghanistan after the withdrawal of the Soviets demonstrated the lengths that hostile intelligence agencies would go to infiltrate the movement, and there are documents and testimonies that confirm how serious al-Qaeda leaders took counter-intelligence. Abu Musab al-Zarqawi’s extensive interactions with a ubiquitous Jordanian intelligence service before his founding of the Islamic State movement surely influenced the policies and practices implemented by the leader in his new Iraqi home after 2002. To summarize, clandestine organizations that survive the punishment that the Islamic State has endured for over a decade, by the very best counter-terrorism forces in the world, eventually develop excellent operational security measures and understand from an insurgent perspective how to prevent the undermining of the state.

Conclusion

Nibras Kazimi has spent over a decade traveling and working in his native Iraq, and smartly commenting on its politics. In 2011, when most others had moved on from closely examining the insurgency, Kazimi made some important observations about his own mistakes:

Operationally, I went wrong by trying to understand the network of the non-Al-Qaeda actors as having their origins in the Saddam regime, as former officers, security officials and Ba’athists. What I missed was that there was a supra-network of young Salafists and other assortment of young Sunni Islamists who came to age during the 1990s - many of whom spent time in Saddam’s prisons and who all know each other -alumnae went on to become Al-Qaeda, the Islamic Army, the Ansar al-Sunna, the Army of the Mujaheddin and the 1920 Revolt Brigades. This supra-network led the insurgency, and recruited the ex-regime officers and Ba’athists as sub-contractors of the jihad; the Saddamists worked for the Salafists from the very beginning, not the other way around.

It took this insightful observer several years to come to this conclusion, but it is one that we should take seriously if we are to truly understand the Islamic State’s previous return from the dead, as well as try to predict what will happen when the “caliphate” collapses. Kazimi is not alone in this realization. Fawaz Gerges in his recent history of “ISIS” called the Ba’athist influence hypothesis “misleading and reductionist… overlooking internal and external, structural conditions in Iraq and Syria that fueled the group’s revival.”

This exploration of Ba’athist influence on the Islamic State movement reinforces Kazimi’s and Gerges’ insights, and demonstrates that the sentiment described by Reuter in his influential article on Haji Bakr–that ISIS is a non-religious power accumulator with little connection to the jihadist trend–is categorically false. That Reuter could make this statement based on genuine captured documents shows that despite the availability of credible information, it is still possible to make erroneous deductions based on limited glimpses into complex organizations. The Islamic State, like its rival al-Qaeda, deliberately recruited former regime members for their military experience early in their existence. Once in the organization, they almost exclusively served in military and command roles–a key function in an insurgency to be sure–but not the most important. In revolutionary war, it is the political and social aspects of the conflict that dominate the action and will determine the outcome. The technical requirements of modern warfare and weaponry absolutely demand an expertise in military operations. But outside of war-fighting functions and internal security, the former regime members in the Islamic State were simply not to be found. Time and time again, the various leaders of the Islamic State installed religious experts, who could reliably interpret and uphold the legitimacy of the so-called caliphate project, into its important governing structures and departments–such as its groundbreaking media department, its religious education programs, its wealth management, etc. Certainly the FRE contributed in a significant manner to the hybrid military campaign that consolidated extensive terrain in Syria and Iraq between 2012 and 2014, and this recognition certainly deserves the attention it has received. The problem with this attention is the need for balance; in looking at it from the Islamic State perspective, their legends are presented as a broad mix of people: homegrown Salafis, FRE, and immigrants.

Beyond the presence of some very prominent FRE in the senior ranks of the Islamic State, and probably scores scattered throughout the mid-level ranks, there is little evidence of any deep Ba’athist influence on the evolving structure or the enduring ideas of the organization. Instead, early adopters of the Salafi-jihadist trend were the ones who shaped the organizational culture during the decade-long struggle to establish an Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. As such, our efforts to understand the ability of the Islamic State to remain a coherent entity should focus on its ties to the global Salafi community, foreign fighter induction networks, and certainly its demonstrated ability to recruit among local tribes in Iraq and Syria–and much less on a dying ideology from yesterday–in order to avoid a very tainted view of this organization on which to base strategic and operational decisions.

About the Author

Craig Whiteside is a professor at the Naval War College Monterey where he teaches national security affairs, and a fellow at the International Centre for Counter Terrorism (ICCT) – The Hague.

This work is licensed under a external pageCreative Commons Attribution 3.0 Licensecall_made. (CC BY 3.0)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.