The Effects of Ceasefires in Philippine Peace Processes

23 Jan 2019

By Ryland, Reidun, Tora Sagård, Peder Landsverk, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, Håvard Strand, Siri Aas Rustad, Govinda Clayton, Claudia Wiehler, Valerie Sticher and David Lander for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by external pagePeace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)call_made in December 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of the Republic of the Philippines Presidential Communications Operations Office/Joey Dalumpines.

The use of ceasefires by belligerent parties varies greatly across conflicts. In some cases, parties agree to a continuous stream of largely ceremonial ceasefire agreements that have little or no effect on the violence. In other conflicts, parties fight on for years without an agreement, but then develop a relatively stable and effective agreement that quickly reduces or terminates hostilities. This PRIO Paper will examine the use of ceasefires in two significant conflicts in the Philippines and analyze their effects on the level and extent of violence.

Brief Points

- Between 1989 and 2017, the Philippines had 149 ceasefires, of which 113 were in the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) conflict and 35 were in the Mindanao conflict.

- 36 ceasefires were related to peace processes.

- 21 ceasefires were declared bilaterally (i.e. both parties agreed to cease hostilities simultaneously), and 124 unilaterally (i.e. only one party committed to ceasing violence).

- In the CPP conflict, ceasefires have led to a short-term decrease in violence, but this has not lasted in the long run.

- In conflicts with multiple actors, the influence and role of ceasefires becomes harder to observe.

The Philippine Conflicts

The Philippines has been hard hit by several conflicts, and there is often more than one conflict active in the country at a time. Since the 1970s, the two most significant conflicts in the country have been the conflict over governance between the Government and the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) – hereafter referred to as the CPP conflict – and one over the territorial status of Mindanao – here referred to as the Mindanao conflict – involving a number of different actors.

The conflict over governance, with the CPP as the main antagonist, has seen a regular string of ceasefires declared, but these have most often been short and insignificant. In contrast, in the Mindanao conflict, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) signed a ceasefire with the Government in 1994 as part of a peace process, which ended with the 1996 peace agreement, and again in the 2000s ceasefires were leading up to a peace agreement between the Government and Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). However, the conflict persisted as splinter groups rejected the peace process.

The CPP conflict is rooted in the HUK rebellion (1946–1954), but reemerged in 1969 with CPP, a HUK splinter organization, in opposition. The CPP conflict quickly escalated, fueled by anti- US sentiment, desire for land reform, and the brutal policies of President Marcos, as well as, initially, the provision of weapons from China.

The election of Corazon Aquino initiated a peace process, which failed and was subsequently replaced by a massive military campaign. This conflict therefore reached a peak in violence in the early 1990s, without a military victory for either side.

The Aquino period also saw other actors involved in the CPP conflict. CPP had several splinter groups, of which the Alex Boncayao Brigade was the most significant, and elements of the armed forces staged several coup attempts against the government.

The second conflict is the Moro insurgency of the Mindanao Islands. In this conflict, Moro Muslim rebel groups have been fighting for an independent Muslim state in the southern parts of the Philippines. The Mindanao Islands is a marginalized area. Since the start of the insurgency, a total of eight military groups have been active in this conflict. Over the past 30 years, the two main groups have been the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). However, splintering and various factions of these groups have made the conflict more complex. In 2016, the Islamic State (IS) also became a part of the conflict, leading to a sharp increase in violence in the southern region.

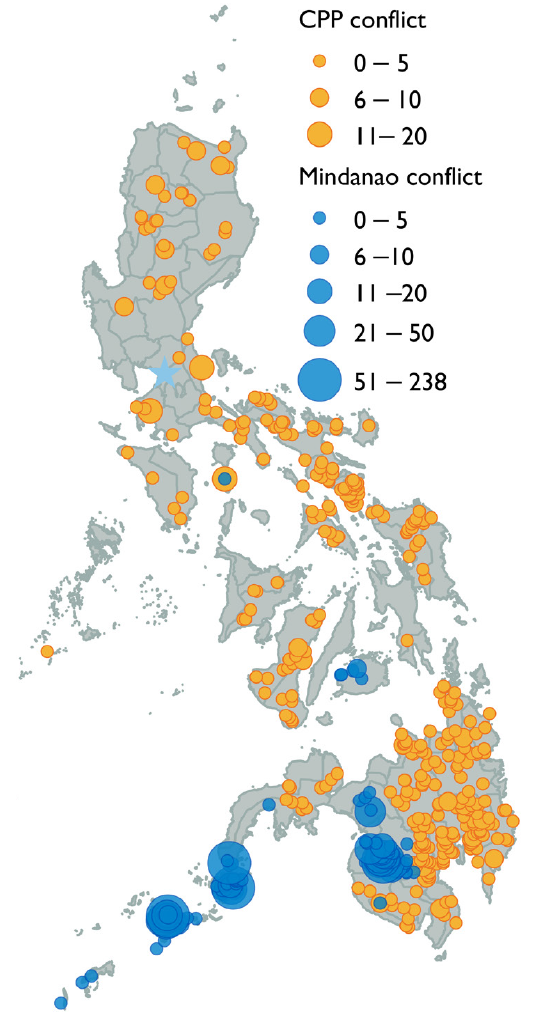

Figure 1 shows the distribution of conflict events and battle deaths in the two conflicts between 2013 and 2017. The CPP conflict has the largest extent and the highest number of events, but the Mindanao conflict, limited to the southern islands, has been more severe in terms of battle deaths.

Ceasefires in the Philippines

Between 1989 and 2017, 149 ceasefires were declared in the Philippines. The majority of declared ceasefires were related to the CPP conflict (113). In the Mindanao conflict, 35 ceasefires were declared, mainly by the two main military groups, MILF and MNLF, but also with some of the other militant groups operating in the area (Moro National Liberation Front Misuari faction (MNLF-NM), Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), and Maute Group).

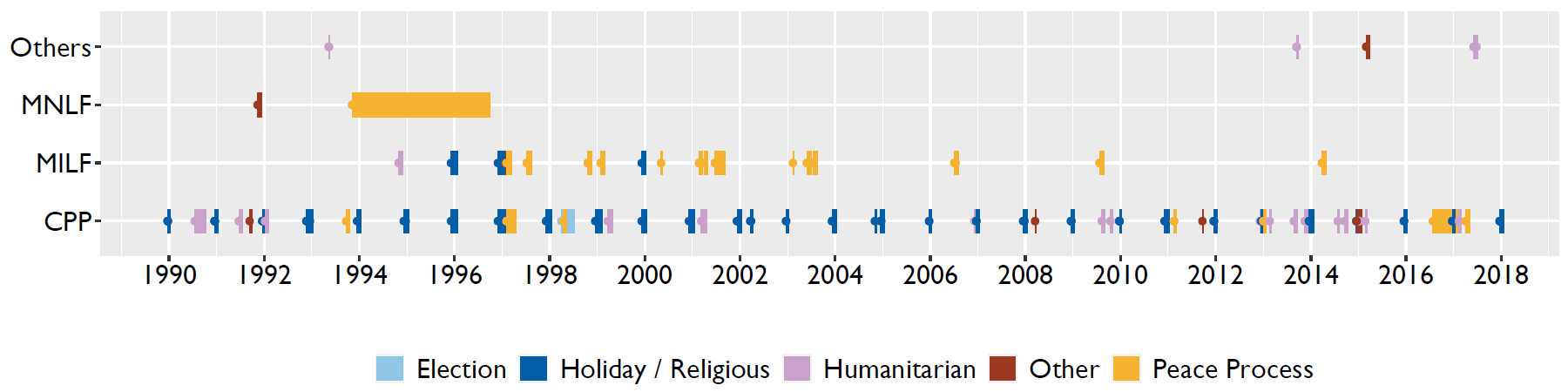

As Figure 2 indicates, more than half of the ceasefires are related to religious holidays. Every year, the Government declares a unilateral ceasefire with CPP over the Christmas holiday, and in most years CPP has reciprocated it. In 2018, however, it was CPP who first announced the Christmas ceasefires; currently, the government has not reciprocated the gesture.

Occasionally there have been ceasefires related to Eid in the Mindanao conflict. These ceasefires typically only last for a few days. This pattern can be seen in many conflicts, but it is particularly pronounced in this context. Out of the 149 ceasefires that were declared, 36 are clearly linked to the onset or continuation of a peace process, while 27 are related to humanitarian motivations, mainly natural disasters or the rescue of civilians caught in the crossfire.

An important distinction is between bilateral and unilateral ceasefires. In our coding, a bilateral ceasefire is a mutual agreement between two or more actors. A unilateral ceasefire instead refers to when only one group ceases hostilities alone. In the Philippines, we observed 21 bilateral and 124 unilateral ceasefires. However, in many cases the parties sign mutual unilateral agreements, such around religious holidays. We also see several examples of reciprocal unilateral ceasefires, rather than a bilateral ceasefire, such as between the CPP and the Government in August 2016, after the inauguration of Rodrigo Duterte as President (see below).

CPP Peace Processes and Ceasefires

The conflict between the CPP and the Government was at its most intense in the late 1980s and early 1990s, following a failed peace process in the mid-80s. During the 1990s, President Fidel Ramos initiated a renewed peace process, resulting in several ceasefires. In the late 1990s, however, the peace talks stalled, and the conflict re-escalated.

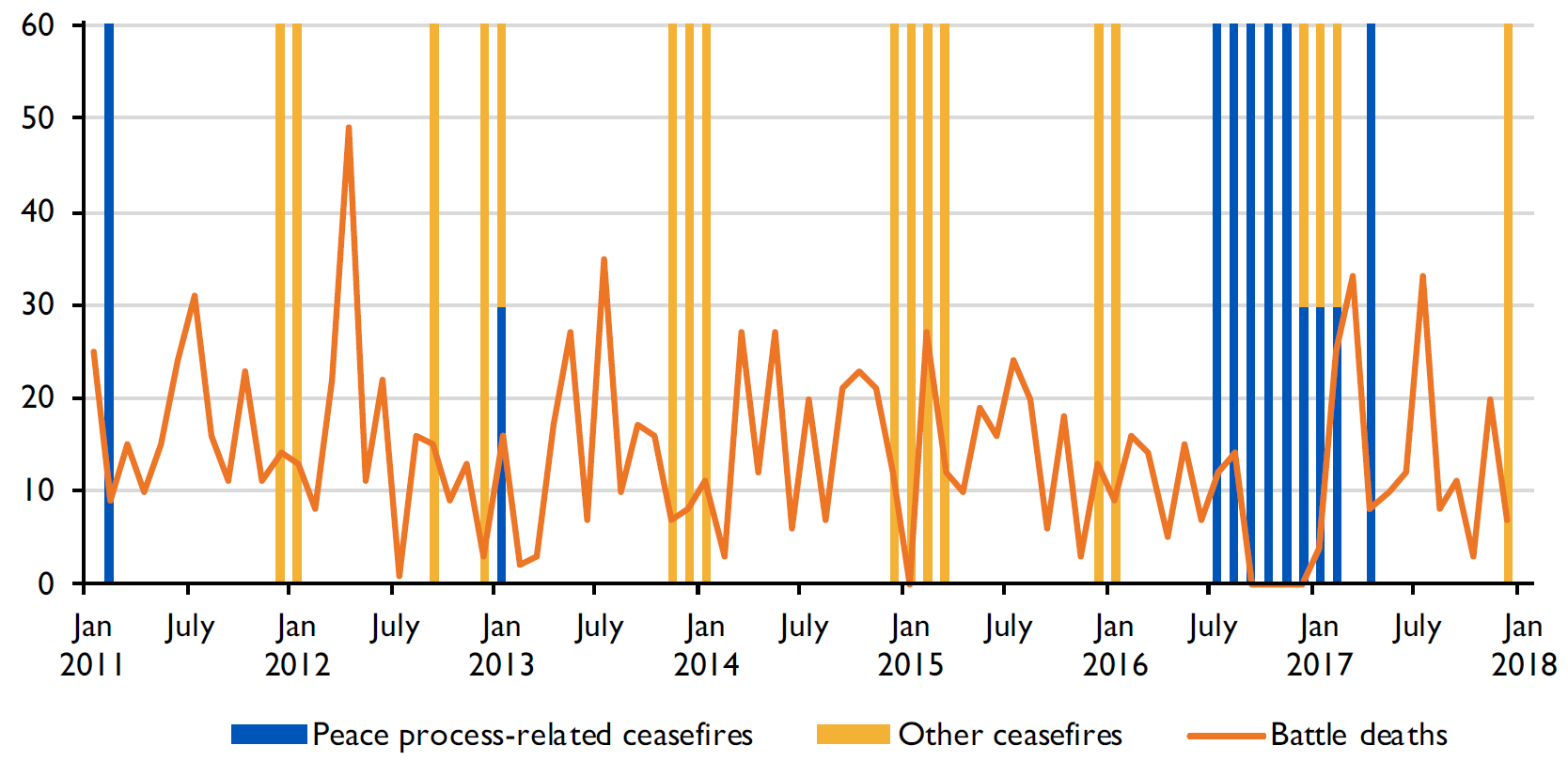

Norway became a third-party mediator in the early 2000s. In 2011, formal talks between the Government and the CPP were resumed. Figure 3 shows the monthly intensity of the CPP conflict between 2011 and 2017. During this period, several ceasefire agreements were signed.

If we compare levels of violence in the months prior to and after the signing of a ceasefire agreement which is related to the peace process, we see a significant drop in violence. This constitutes some preliminary evidence that ceasefires do have a short-term effect in reducing violence. Whether this is always the case, and the extent to which ceasefires also shape long-term behavior is not yet clear in existing research.

Duterte and the CPP Peace Process

Rodrigo Duterte came into power in June 2016. In his first State of the Nation address, he declared a unilateral ceasefire against CPP, which was then reciprocated by CPP in August of the same year. In addition, Duterte released 22 prisoners, including the CPP chairman Benito Tiamzon.

Peace talks were resumed in Oslo in late August 2016, and the parties declared mutual unilateral ceasefires. This was followed by a period of low violence (see Figure 3). However, the relationship between the Government and the CPP broke down in early 2017. In February 2017, the CPP let the August ceasefire expire due to a conflict over the release of political prisoners. In response, Duterto canceled the peace talks and declared an all-out war against the CPP, resulting in a significant increase in violence.

A new ceasefire was forged in negotiations that took place in the Netherlands in April 2017, but the violence has continued. Following a war of words between CPP co-founder Jose Maria Sison and Duterte during the summer of 2017, Duterte declared the end of the peace talks and proclaimed the CPP-NDF as a terrorist organization.

The Mindanao Peace Process

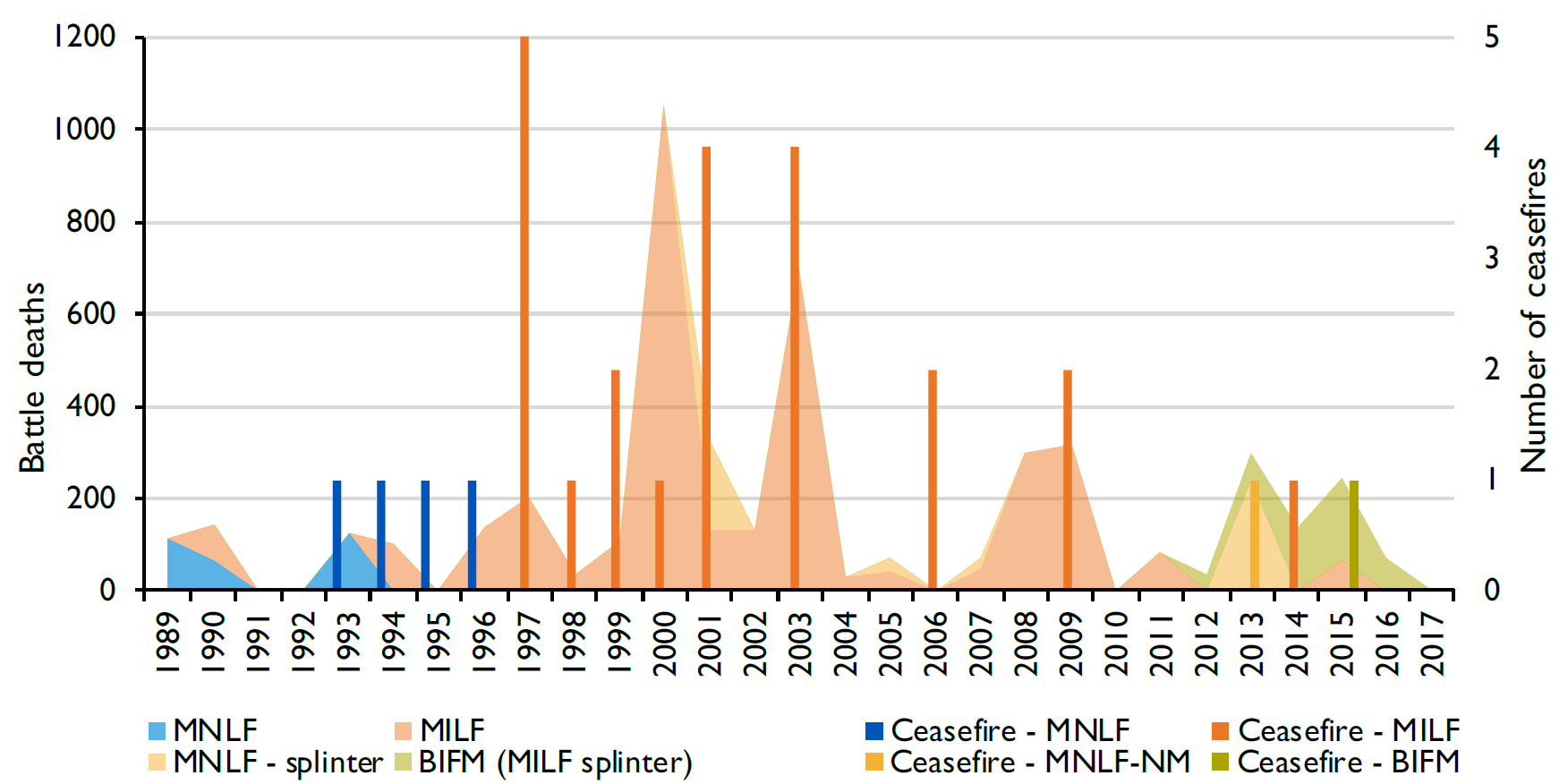

The Mindanao conflict has seen several attempted peace processes. In 1992, the Ramos government and MNLF began talks that culminated in the 1996 peace agreement. MNLF was given a major political role in an autonomous region. Since 1993, MNLF has not been involved in violent conflict.

However, in 2001, violence between MNLF factions (MNLF-NM) and the Government broke out after MNLF founder Nur Misuari was removed from office on corruption charges. Since then, occasional outbreaks of violence involving MNLF factions have been recorded. Figure 4 indicates the level of violence committed, and the number of ceasefires declared by each group.

The 1996 peace agreement did not include the more Islamist group, MILF. Nevertheless, MILF gave tacit support of the process, resulting in a period of relative peace in the late 1990s, which included several ceasefires between the Government and MILF. This ended in March 2000, when the Estrada government began a military offensive against MILF.

Over the course of the conflict, violence periods were often punctuated by or ended through a ceasefire. Towards the end of the 2000s, violence between MILF and the Government again subsided. Peace talks resumed, and in 2012 the Framework Agreement on Bangsamoro was established, followed by the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro in 2014. However, in 2013 a MILF splinter group, the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Movement (BIFM), appeared, renouncing the peace process.

In 2013 and 2015, ceasefires with the splinter groups MNLF-NM and the BIFM were declared. However, both of these were related to humanitarian crises rather than a peace process. Thus, as of now, there is no evidence of an ongoing peace process between the Government and these splitter groups.

Ceasefires, Multiple Stakeholders and Factionalization

Ceasefires are not only a means of ending violence; they should also be understood as a part of the political process which is closely related to the dynamics of the conflict. In the case of the Philippines, ceasefires played different roles in the two main conflicts. In the case of the CCP conflict, the ceasefires were plainly a part of negotiation processes, between two clearly defined conflict parties.

In the Mindanao conflict, the picture is more complex, with multiple stakeholders and ceasefires. While the ceasefires and peace agreement in the period 1994–1996 did not lead to an overall decrease in violence, they did end the conflict between MNLF and the Government. Similarly, the peace process between 2012 and 2014 seems to have reduced the violence between MILF and the Government, but we see an increase in violence from the MILF splinter group BIFM. In 2017, the level of violence by the splinter groups decreased. However, the overall violence in the area increased due to IS.

Kolås (2011) suggests that a ceasefire can affect the dynamics of a conflict in several ways. First, it can change the internal cohesion among the belligerents. In the Mindanao conflict, during the peace process, groups splintered into pro- and anti-negotiation groups, offering some anecdotal evidence of this effect. The violence thus continues.

Second, ceasefires affect the relationships between the non-state conflict actors. This might explain why in 2011, MILF negotiations with Government resulted in fighting between MILF and BIFM.

Finally, ceasefires can either create new opportunities or pose limitations for the militants in terms of operational space. In principle, the pause in violence could create opportunities for new groups to recruit from the inactive group. This might explain the growing presence of IS in the Mindanao conflict. This could lead to further polarization and extremization of the conflict, and thus worsen the prospects for a peace process with the splinter groups.

In much of the current research on ceasefires, there is often an assumption that a ceasefire fails if it is not associated with a reduction in violence. The case of the Mindanao conflict suggests that this is not always so straightforward. With the new dataset that we are currently developing, we focus on conflict actors rather than on conflicts, so that in future we will be able to isolate the influence of a ceasefire on the behavior of different groups.

We can test the effect of a ceasefire on the relations between the actors involved. Further, we can also test how this affects the conflict dynamics and the relationships between other conflict actors. This data will be important for understanding both the global trends and interactions between groups in multi-stakeholder conflicts such as in Afghanistan and Syria.

About the Authors

Reidun Ryland and Tora Sagård are Research Assistants; Peder Landsverk is a Master’s Student; David Lander an Intern; and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård and Siri Aas Rustad are Senior Researchers at PRIO.

Håvard Strand is Associate Professor at UiO and Senior Researcher at PRIO.

Govinda Clayton is Senior Researcher, Claudia Wiehler is Research Assistant and Valerie Sticher is a senior program officer at the CSS at ETH Zürich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.