Russian Analytical Digest No 207: Mobilizing Patriotism in Russia

2 Oct 2017

By Ekaterina Khodzhaeva, Irina Meyer, Svetlana Barsukova and Iskender Yasaveev for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 26 September 2017.

Introduction

The Growing Role of the Patriotic Agenda

This edition of the Russian Analytical Digest examines the growing role of the patriotic agenda in Russian politics and changes in the “official” meaning of this term and its interpretation by the authorities in recent decades. The first article, written by Ekaterina Khodzhaeva and Irina Meyer (Olimpieva), analyzes the system of patriotic education in Russia with a primary focus on federal programs. The analysis demonstrates considerable changes in the programs’ purposes and priorities over the last decade. In the next article, Svetlana Barsukova looks at the role of patriotism in forming consumer preferences among the Russian population. She considers the interplay of market and ideological factors in the formation of attitudes toward imported goods during the post-Soviet period. The third article by Iskender Yasaveev examines militarization of the national idea by the Russian political authorities during the third presidential term of Vladimir Putin. The country’s increased competitiveness gave way to militarized patriotism.

Mobilizing Patriotism in Russia: Federal Programs of Patriotic Education

By Ekaterina Khodzhaeva and Irina Meyer

Abstract

The paper describes the system of patriotic education in Russia. The main focus is on the federal programs of patriotic education and their evolution since 2000. The analysis demonstrates how the features and priorities of federal programs have been changing with the growing significance of the patriotic agenda in the Russian political context.

The patriotic revival is getting top priority in Russia in recent decades. Patriotism is gradually becoming the leading state ideology, with patriotic education serving as the key mechanism for mobilizing the Russian population to support the political regime. The system of patriotic education (hereafter PE) was restored from the Soviet past legally and administratively in the beginning of the 2000s. Today, PE is well incorporated into the Russian legislative system and includes federally funded programs that motivate state agencies and executive bodies to implement PE in various fields, including youth and educational policy, leisure and cultural activities, media outreach, and many others. Patriotic education is also carried out by civil society organizations, such as veterans’ groups and other organizations with a military-patriotic orientation, religious (primarily Orthodox) communities, Russian Cossacks, volunteer groups, and youth clubs among others.

PE is implemented at all levels of state governance via specially developed federal, regional, and local programs. More than 30 federal agencies have their own internal programs of PE. At the federal level, coordination of all PE activities is carried out by the Russian Pobeda (Victory) Organizing Committee that was created by presidential degree in August 2000. The Russian president chairs the Committee himself. Coordination of the PE federal programs is carried out by the Russian Center for Civil and Patriotic Education of Children and Youth (Russian Patriotic Center) that was established for this purpose by the Russian Federal Agency on Youth Affairs in 2016. The Ministry of Education and Science, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Defense perform as the main agencies of the federal PE program. At the regional and local levels, special coordinating bodies or councils on PE have been established by regional and municipal authorities. They also have their own programs and provide financial support for various PE projects. Many Russian regions have adopted and enacted regional PE laws.

The Growing Significance of the Patriotic Agenda

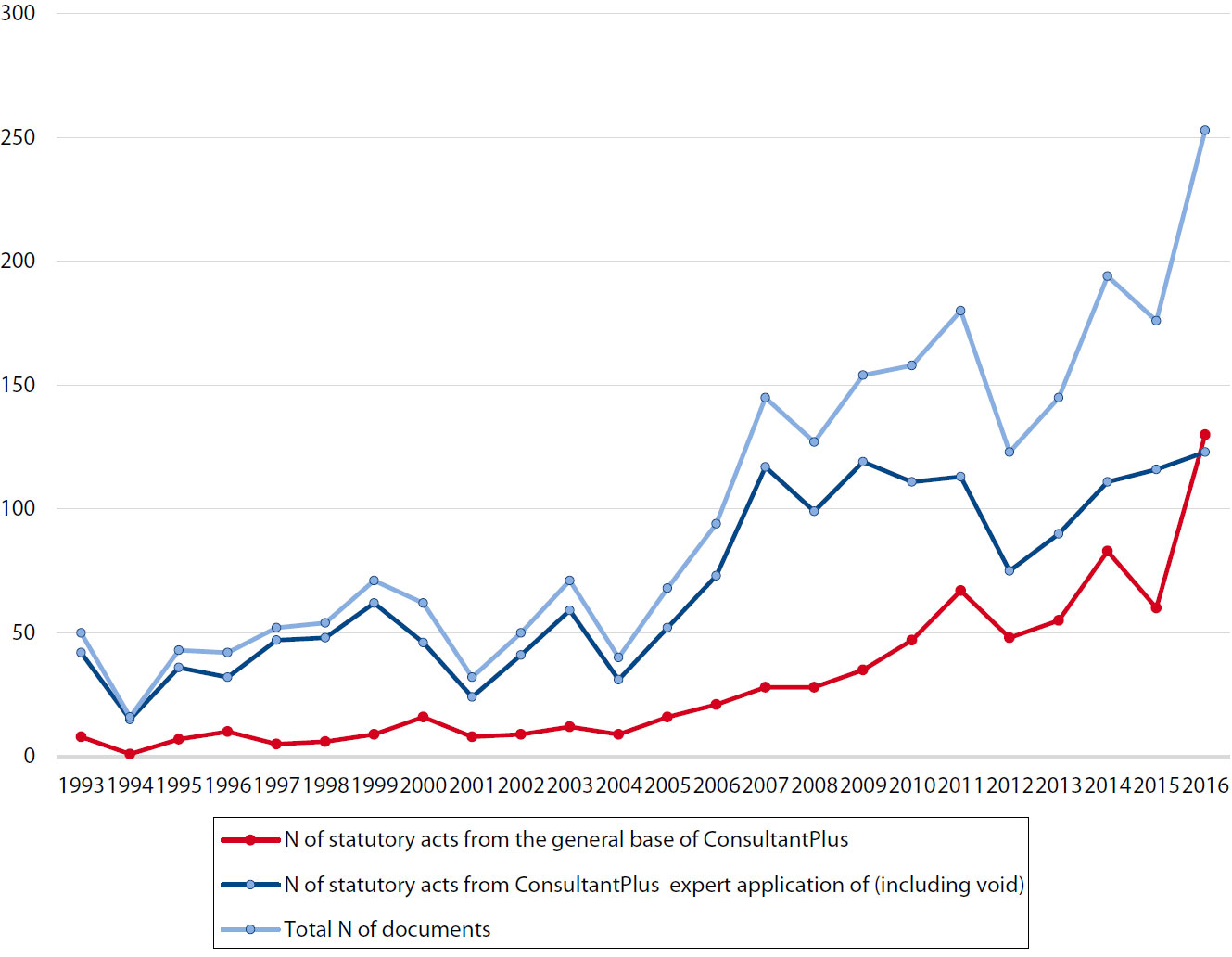

The growing significance of patriotism is reflected in the increasing penetration of this term into legislative documents. Figure 1 on p. 6 shows the results of a text search for the morpheme “patriot” in the database of the computer system Consultant Plus, which provides legal reference information. The search was made in both the general and expert databases for professional legal documents that include besides basic laws and regulations, all kinds of normative regulating documents including by-laws, orders, instructions, etc.

As the trend line demonstrates, during the first post-Soviet decade, the number of regulations referring to the subject of patriotism was relatively constant and small, less than 10 texts per year (which could also reflect the low level of the overall regulatory action during that period). While the subject of patriotism and patriotic education never left the political agenda completely during the 1990s, it appeared in the normative documents because of the activities of the Ministry of Defense and due to the preparations for various military holidays, such as the 50th and 55th anniversaries of the WWII Victory in 1995 and 2000.

The first increase in references to a patriotic agenda in the regulatory documents resulted from the development of the first federal program of PE during Vladimir Putin’s first presidency. Since the very beginning of his presidency, Putin constantly referred to the patriotic agenda in his speeches and inevitably touched on this subject during his annual direct “hot-line” dialogues with the population.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, the rise in references to the patriotic agenda has become a permanent trend. The increase refers to both the general and expert databases, which means that the laws mentioning the patriotic agenda were not only adopted but actively implemented in practice through various normative regulations, such as departmental instructions, orders and the like. Another reason for the increase is the intensive development of regional legislation on PE in recent years. Today, almost every region in Russia has adopted its own law and/or program on PE. At the same time, multiple attempts to develop the federal law on PE that have been undertaken since 2001 have not succeeded; the most recent draft of the law in still under discussion in the State Duma.

The sharpest rise in the patriotism curve affecting legislative documents can be seen in 2014 after the annexation of the Crimea, reflecting the general situation of patriotic hysteria during that period. In 2015, the overall number of mentions for the word “patriot” in Russian normative documentation exceeded 250.

Federal Programs

Since 2000, state policy in the field of PE has been implemented via the federal programs “Patriotic Education of Citizens of the Russian Federation” adopted by the Government of the Russian Federation every five years. They are usually referred to as the first, the second, the third and fourth federal programs (2001–2005; 2006–2010; 2011–2015, and 2016–2020 correspondingly). While the main principles of PE remained the same through all four programs, the emphasis and priorities of each program have been changing over time, reflecting the changes in political and ideological contexts.

The primary purpose of the first PE federal program (2001) was to establish the nation-wide PE system, including legal regulatory and administrative support. The Russian president and government ordered the work and it has been carried out since 1999 by the interdepartmental working group, which included representatives of 29 ministries, state agencies, veterans’ and other public organizations. Another purpose of the first program was the development of the nation-wide Concept of PE that was adopted by the government in 2003. The notion of patriotic education was determined as “… systematic and purposeful activity of government bodies and organizations to establish a high patriotic consciousness among citizens, a sense of loyalty to their Fatherland, readiness to fulfill civil duty and constitutional obligations to protect the interests of the Motherland. Patriotic education is aimed at the formation and development of an individual who possesses the qualities of a citizen who is a patriot of the Motherland and who is able to successfully fulfill civil duties in peacetime and wartime.” The program also defined the notion of “military-patriotic education” as an integral part of patriotic education in general.

The second PE federal program (2006) was primarily focused on the need to foster tolerance and friendship among Russian people reflecting intensive debates on these issues during that period. However, the idea of tolerance did not get much attention in the subsequent PE programs, except for general statements that PE should take into account the multi-national character of the Russian population. While the first program postulated the entire Russian society as the main target group of PE, the second program emphasized the need to foster patriotism among young people. This trend continued in the subsequent programs that emphasized the role of educational institutions as “integrating centers of joint educational activities of the school, family, and public organizations (associations).” The increasing emphasis on youth reached its peak during the fourth PE program when the Russian Federal Agency on Youth Affairs created the Russian Center for Civil and Patriotic Education of Children and Youth (Russian Patriotic Center) to replace the Russian Military Center as the main coordinator of PE programs at the federal level.

Since 2011, one can see the strengthening of the “protective” trend in PE. Thus, among the main target goals of the third program was “overcoming extremist manifestations among particular groups of citizens,… and strengthening national security.” At the same time, there are growing attempts to ensure the continuity of the contemporary system of PE with Soviet efforts to provide a military-patriotic education for young people. Thus, the third program speaks of the revival of the traditional and well-established “Soviet” forms of PE work, such as “military sports games and other events aimed at the military-patriotic education of the youth.” The fourth program that started last year goes further by claiming that existing forms of military-patriotic education are insufficient and asserts the necessity of retraining the people carrying out educational work to teach them new methods. Besides military camps, clubs, and games, the program encourages the creation of the so-called “cadet classes” in ordinary schools. The cadet classes are designed primarily for boys (rarely including girls) beginning from the 5th or 7th grades. The schoolchildren in cadet classes wear a uniform (often black, military-style, with aiguillettes); the class usually has a banner, an emblem, and a “code of honor.” The students use special forms of greeting at the beginning of the lesson and while addressing the teacher. They also have an oath, which every cadet says when entering a cadet class. The second half of the school day for cadet students includes combat and sports classes, as well as various competitions with the guidance of the curator, usually a former military officer. It is expected that many schoolchildren after cadet classes would choose military careers. Cadet classes are not connected only with the military and do not mandate military careers for the students. Almost every law enforcement agency (Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Emergency Situations, Investigative Committee, Federal Service for Punishment Execution, and even the Customs Service) in Russia has opened its own cadet classes in schools all over the country in order to recruit students for future jobs.

Participants and Funding

The central part of the federal PE program is the list of specific measures and activities, which specifies the funding and participants for each event. Along with federal and regional authorities and local self-government bodies, the list of participants includes various cultural institutions, museums, mass media, public organizations (primarily veterans’, youth, and religious—mostly the Russian Orthodox Church, but also the Council of Muftis of Russia), Cossack organizations, and others. Against the backdrop of a general ideological confrontation with the West, PE increasingly appears as a matter, in which only the trusted organizations loyal to the Russian authorities should be involved. Thus, in 2016, a bill on amendments to the federal law “On Public Organizations” was introduced to the State Duma prohibiting organizations involved in PE from receiving foreign funding.

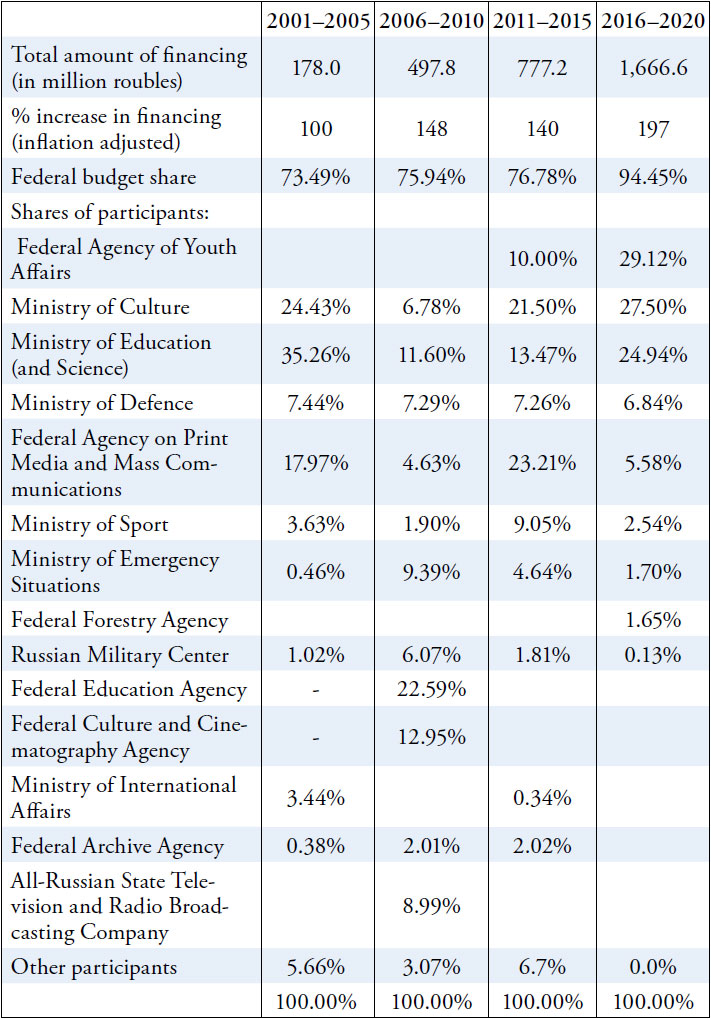

The funding for the PE programs comes directly from the federal budget. The share of the state in overall funding has increased from 73.49% in 2001 to 94.45% in 2016 (see Table 1 on p. 7). Since the requirement of cofunding in organizing events in Russia is usually a formality, the state effectively funds all PE in Russia. The overall spending on each subsequent PE program has been increasing significantly: by 1.48 times in 2006 compared with 2001, and by 1.4 times in 2010 (Table 1 on p. 7, inflation-adjusted data). The fourth program envisages nearly a doubling in financing. Most of the state funding is shared by the four main participants of the PE programs: the Federal Agency on Youth Affairs (the Russian Patriotic Center) (29.12%), the Ministry of culture (27.50%), the Ministry of Education and Science (24.94%) and the Ministry of Defense (6. 84%). The number of agencies and other bodies participating in the PE programs receiving state funding has been changing over time with maximum of 22 in the second program and a minimum of nine in the most recent fourth program. However, the federal bodies have to participate in the implementation of the PE programs regardless of whether they receive state funding or not. Thus, the fourth PE program lists 19 federal ministries and agencies among the program participants. The list also includes such organizations as the Voluntary Society for Assisting the Army, Air Force and Navy, the Russian Military History Society, the Russian Military Historical Society, the Russian Fleet Support Fund and registered and non-registered military Cossack associations as well as public and non-profit organizations.

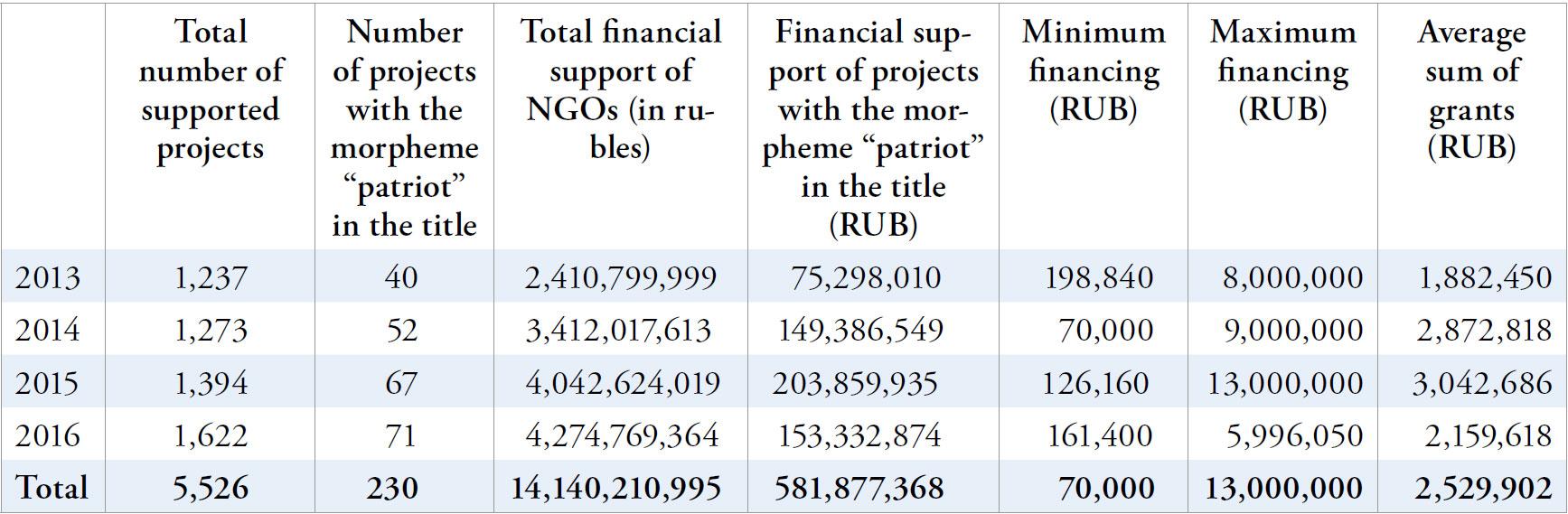

In addition to the direct support for the federal PE programs, other sources are used to support the patriotic agenda, such as e.g., the Presidential grant program for Russian non-profit organizations that was launched in 2012. A text search on the morpheme “patriot” in the name and description of projects supported by this program has shown the constant growth in the number of “patriotic-oriented” projects (see Table 2 on p. 8). While in 2012 none of the supported projects contained the morpheme “patriot,” from 2013 the number of these projects started to increase. From 2013 till 2016 there were 230 projects with “patriot” in the title that received overall about 580 million rubles from the federal budget. (This is the minimal estimation, because the search does not indicate the projects that also include patriotic component but did not indicate it in the project’s title). The smallest among the grants (70,000 rubles) was given to “the Ulan-Ude and Buryat Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church” for the military-patriotic club “Ostrov” (Island) in 2014. The biggest grant (13 million in 2015) was provided to the All-Russian Veteran movement “Boyevoe Bratstvo” (Battle Brotherhood) to support youth patriotic clubs in regional departments. The well-known motorbike club “Nochnye volki” (Night wolfs) received 3.5 million RUB in 2013 and 9 million RUB in 2014 for organizing new year’s festivities for children, and 12 million RUB in 2015 for the All-Russian youth center “Patriot.”

In addition, some federal bodies use their own resources to carry out PE. For example, the Ministry of Defense (the Western Military Command) sends its inspectors in patriotic education to general education institutions. It also promotes the Russian militarypatriotic movement “Young Army” created in 2016 in all Russian regions. The movement is financed through the Russian Voluntary Society for Assisting the Army, Air Force and Navy. Now the movement includes 117,000 people from all over the country. The financial support of this project is provided not only by the Ministry of Defense but also from semi-state banks. In 2016, VTB-bank provided 150 million rubles for the Young Army project (<https://www.dp.ru/a/2016/09/06/ VTB_videlit_150_mln_ruble>)

Evaluation of the PE Programs

The system of evaluation of the PE programs has been constantly changing as well. The first program formulated unclear and virtually unmeasurable indicators, such as “moral unity of society,” “revival of true spiritual values,” “social and economic stability,” “readiness of citizens to defend the Fatherland,” etc. The only widely cited quantitative indicator was the number of focal points and councils, programs and other regulations on PE developed at the regional and local levels. The second program developed an appendix in which quantitative parameters were complemented by qualitative indicators, such as specific spiritual and moral characteristics of the population. Since the third program, a special monitoring program designed to measure the effectiveness of PE was established with about 3 million rubles from the program budget each year.

Despite the measurement and evaluation systems, the effectiveness of the PE programs remains unclear, because the indicators reflect the process of program implementation rather than its result. Many indicators can be easily simulated and even fraudulent, others are too easy to achieve. For example, the conferment of the names of the Heroes of the Soviet Union and Heroes of the Russian Federation to the organizations does not require any investments or administrative activities. Perhaps this is the reason why by the end of 2015, 4,800 educational organizations and military-patriotic clubs received such designations.

Among the positive indicators are the growth in the number of cadet schools, as well as cadet and Cossack classes in regular schools. According to a recent assessment, the number of cadet schools in Russia by the end of 2015 was 177 with 61,846 students. In addition, about 7,000 cadet and Cossack classes operate in Russia. In 2015–2016, according to Ministry of Education, the number of cadet classes in Russia increased by 50 percent. The efficiency of leisure and sports work is measured by the number of schoolchildren who took part in presidential sports competitions and the number of military sports boot-camps. According to monitoring results, in 2010/11—7.5 million students, and in the 2014–15 academic year—10.1 million students from 37,200 general education institutions. The quality of work in these camps is not taken into account. The fourth program also looks at how many specialists in education have undergone PE retraining, the proportion of citizens who passed the Civil Defence Squads test, among other indicators.

Conclusion

The Russian version of patriotism has been changing with the development of the political agenda and the general political context. While the first two programs included discussions on tolerance and the elaboration of the new concept of Russia as an independent and strong state, the third and the fourth programs mainly concentrated on restoring the Soviet experience of PE and strengthening the “protective discourse.” Today, patriotic education in Russia aims at a younger generation and tries to combine the old well-established Soviet tools of military-patriotic education with the new methods and positive images of the past.

Patriotism is generally defined in Russian legislation and by program participants as a “state affair.” Almost all patriotic events and initiatives, regardless of whether they are organized by the state bodies or by NGOs, are paid for from the state budget. The dynamic of evaluative criteria for PE programs is a good example of how Russian governmental structures understand the effectiveness of PE. Each new program introduced a more detailed and quantitative assessment system. These new procedures are forcing the instructors who actually implement PE program to increase the number of events (at least on paper), but not necessarily boost their quality and real impacts.

Recommended Reading

- B. Bruk. What’s in a Name? Understanding Russian Patriotism. Report of Institute of the Modern Russia. <https:// imrussia.org/en/research>

- What is the beginning of the Motherland: the youth in labyrinths of patriotism. Ed. E. Omelchenko, H. Pilkington, Ulyanovsk, Ulyanovsk State University press, 2012. In Russian (С чего начинается Родина: молодежь в лаби- ринтах патриотизма). Под ред. Е. Омельченко, Х. Пилкингтон. – Ульяновск: Изд-во Ульяновского государ- ственного университета. 2012)

- Gabovitsch, M. (ed.), Memorial and Festival: Ethnography of the Victory Day (Памятник и праздник: этнография Дня Победы). Moscow, NLO Press (in Russian ) (in print).

About the Authors

Ekaterina Khodzhaeva works as Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Comparative Political Studies, the North-West Institute of Management, Branch of RANEPA. Email:

Irina Meyer (Olimpieva) works at the Centre for Independent Social Research in St. Petersburg as a senior researcher and the Head of the “Social Studies of the Economy” Department. E-mail:

Figure 1: Dynamics In the Number of Regulations Referring to the Issues of Patriotism (Text Search for “Patriot” in the Main and Expert Datasets of the Computer Legal Reference System ConsultantPlus)

Table 1: The Financing of the PE Federal Programs

Table 2: The Distribution of Presidential Grants among Projects with the Morpheme “Patriot” in the Title

Consumer Patriotism: How Russians “Vote with their Rubles” for Great Power Status

By Svetlana Barsukova

Abstract

This article examines Russian consumers’ evolving attitudes toward imported goods during the post-Soviet era. It also considers the role of market and ideological factors in forming consumer preferences. Ideally, consumers should behave purely rationally, reacting only to the quality of a good, prices, and their own limited budgets. In which country a good is produced should not be important. However, in reality, rather than being guided by market signals, consumer views of goods are determined by political factors and moods, which changed considerably through the course of post-Soviet history.

Soviet Shortages and the Love of “Imports”

In the USSR, and especially during its later stages, there were shortages of practically all types of products— clothing, shoes, furniture, household electronics, pharmaceuticals, and food. This does not mean that the shelves in stores were absolutely empty. But what was there was not something that the ordinary citizen wanted to buy. For example, in grocery stores, milk was available, but mayonnaise was more difficult to find. Department stores sold coats produced in Soviet factories, but they were either no longer fashionable or low quality and therefore uncomfortable. (As Klara Novikova, a famous Soviet comedian noted, “the imported blouse ‘flaunts’ the body, while our does ‘not flaunt.’”) In these conditions, foreign consumer goods became symbols of quality, beauty, and fashion, while the taste of overseas delicacies was both wonderful and unusual. In day-to-day discourse, all goods produced abroad were labeled “import,” which a priori gave them a positive connotation. When a Soviet person wanted to say that he bought beautiful new clothes, or reliable electronics, or tasty salami, he said that he had purchased “import.” Members of the older generation even now describe goods as “import” if they want to emphasize the high quality of a product.

Foreign goods typically were distributed though closed channels or blat (see the works of Alena Ledeneva), but occasionally they appeared for sale in stateowned shops in Moscow, Leningrad, and several other large cities. In order to buy these goods, people stood in line for hours. Residents of provincial towns specially came to Moscow to buy imported goods, standing in line in the capital’s department stores some times without even knowing exactly what kind of “import” would be “handed out” on a given day. There was even a famous song by beloved bard Vladimir Vysotsky whose hero came to Moscow from a distant city with a list of goods his relatives had requested and gradually lost his mind standing in various lines. Alternative methods for buying imported goods included flea markets (барахолки), where one could buy almost anything, but for prices that were several times higher than in the state stores. Ironically, many of the goods sold in flea markets as “imports” were actually produced by illegal underground Soviet factories (цеховиками). Nevertheless, during the Soviet period, “import” signified a high-quality good and the fine taste of its owner. The very fact of consuming foreign goods bore witness to the high social status of a person.

Beginning of the 1990s: Unconditional Trust in Imported Goods

With the beginnings of economic reforms in the 1990s, the flow of imported goods into Russia dramatically increased. On one hand, the growing number of businesses began to provide extensive supplies of imported foods and other goods. On the other hand, Russians who lacked jobs and money began to travel to China, Turkey, Poland, and other countries, bringing back goods to sell. The growth of the “shuttle trade” was significant for the survival of the population during the crisis and for the Russian economy in general. In 1994, shuttle traders imported goods worth 8.2 billion US dollars, according to Russia’s State Statistical Committee. In 1995, this sum exceeded $10 billion or 20 percent of all Russian imports. Approximately 10 million people were involved in the trading business, according to several estimates. Along Russia’s borders, various “cities” popped up with services making life easier for the traders, including warehouses and wholesale stores, informal exchange offices to convert hard currencies at profitable rates, and intermediary firms that made it possible for the traders to work without paying taxes. There also appeared institutionalized informal systems for getting around limits on the amount of goods that could be imported including by buying border guards and hiring members of the local population living along the border to transport goods across state lines.

During the 1990s, imported goods were extremely popular for a variety of reasons. First, domestic production dropped dramatically due to the forced economic reforms. Agriculture, in particular, suffered a catastrophic collapse. During the first eight years of reform, from 1990–1998, agricultural output dropped 50 percent.

Second, the population of the USSR was convinced that imported goods were the best quality available. Former Soviet citizens had enormous interest and trust in any “imported” good. This was a time of naive consumption, which many today remember with smiles. However, slowly Russians learned to examine imported goods with a more critical eye. For example, one of the first products to appear on the Russian market was Rama, a famous spread made from vegetable oil, which was advertised as a magic ingredient for sandwiches. The bright packaging and assertive advertising campaign at first conquered the post-Soviet consumer. But Russians relatively quickly figured out that the product was little different than the well-known Soviet margarine, which was also made of vegetable oils. Russians cut back on using Rama in their sandwiches and began to buy it only for cooking.

The faith of Russian consumers extended even to products that turned out to be unhealthy. During the early 1990s, many products imported to the country were low-quality, cheap goods that contained harmful ingredients. One example was the powder “Invite,” which was advertised as being like juice. Its slogan was “Simply add water!” The consumer trust arose from the Soviet experience in which there were no television commercials so that television was considered to provide only “correct” information. Therefore, viewers watched television ads uncritically and believed them completely. They actively bought the power advertised as juice, added water, and gave it to their kids. However, when the parents began to notice that the “juice” turned their kids’ tongues bright colors, they stopped buying it and it quickly disappeared from the Russian market (though humorists long used the slogan “just add water” for their jokes.)

In addition to their disappointment with the market reforms, consumers also continued to lose faith in the imported foods. Memories of the USSR became more positive and Soviet products began to seem ever more natural and healthful in contrast to the goods brought from abroad. People also began to forget how hard it was to buy goods during the Soviet era. The discrediting of the imported foods was connected to the deficits on the Russian market, which meant that importers often brought in low quality goods. Russian still remember “Bush legs” (chicken legs) as emblematic of low quality imports. At a time when real incomes were dropping and there was a sharp plunge in domestic chicken production, the Bush legs helped Russians survive, but as the crisis eased they became a symbol of the low-quality imports no one wanted.

Beginning of the 2000s: The Formation of Differentiating Attitudes to Imported Goods

Toward the beginnings of the 2000s, Russians began to take a more nuanced view toward imports. They learned that imports vary in quality and far from all of them deserve to be trusted. Consumers avidly bought imported automobiles, computers, electronics, clothing and shoes. However, in the food markets, they began to favor domestic products, as all surveys showed since the end of the 1990s. The main qualities they began to seek was the products’ “naturalness” and the absence of “harmful chemicals.”

These new consumer preferences strengthened as the Russian economy grew stronger, especially in agriculture, where conditions gradually ripened to be able to meet the new demands. After the 1998 default, agricultural production began to grow. Grain producers recorded the fastest progress. Since the beginnings of the 2000s, Russia entered the global grain market and is among the top three exporters. Taking into account that the USSR was a chronic importer of grain, the success of the agrarian sector is often used as evidence of the success of the reforms. The growth of these exports is a source for national pride. In official discourse, Russia is described as providing food for “half the world.”

In addition to the growth of grain at the beginning of the 2000s, meat production has also increased, especially poultry and pork. For the first time in post-Soviet history in 2003 Russia introduced quotas on the import of meat. Until then there had been no limits on importing meat and the tariffs had been purely symbolic. Developing animal husbandry had been a national priority for the country and the government set up financial and administrative instruments to support its agrarians. By 2012 Russia met all of its poultry needs and almost met its pork demand and began working on plans to export meat. Production of grain per capita in 2008 was 169 percent of the 2000 level and meat 147 percent. For the period 2005–2010 investment in basic capital in agriculture grew three times, from 79 billion rubles to 202 billion (in real prices).1 The positive changes were so palpable that for 2005–2010 the share of imports in the Russian market fell for poultry from 47 percent to 18 percent.2

The growing sophistication of consumer preferences has had funny consequences for the marketing strategies of the producers. Russian firms making computers, elec- tronics, clothing and shoes typically hide their “Russian origins.” These companies take on English names so that consumers think of their goods as imports. For example, the famous company Vitek, which produces electronics, is Russian, but the name of the firm, packaging, and advertisements adopt a Western style.

Foreign firms which make food products for Russians, in contrast, take names “a la Rus.” For example, the juice market in Russia is effectively divided among the major global companies, however, their product has a primordial Russian name—Dobryi or Lyubimyi among others. The packaging uses Russian folk patterns and the advertising points out the juice is made according to “ancient Russian recipes.” A significant part of the Russian population does not suspect that these juices are made from imported concentrated syrups in Russian factories, many of which are owned by foreign companies. For example, the leading juice company Lebediansky was bought by PepsiCo in 2008.

The juice market is not an exception. Foreign companies invest in many branches of the Russian agroindustrial complex, including in enterprises producing products with typical Russian names. Despite the name, however, they use imported raw materials and equipment. For example, one of the most popular brands of cookies (Yubileinoe), whose history reaches back to prerevolutionary Russia, is made in the Bolshevik factory, which was bought by the French company Danon in 1992. Since the media does not discuss the theme of foreign investment, consumers consider everything made in the territory of Russia to be domestic production.

Escalation of Patriotism in 2014–2017

At the beginning of 2010, President Medvedev adopted a Doctrine on Food Security, which set down the specifics of Russia’s understanding of this topic. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, food security concerns a situation in which the population of a country has the ability to consume food in sufficient quantities and quality for normal life. There is no discussion about the source of the food. But in the Russian Doctrine on Food Security, “security” is interpreted as independence from imports. As Russia prepared to enter the WTO in 2012, the Doctrine was forgotten because its protectionist spirit contradicted WTO principles.

Events in Crimea reanimated the idea of food security as independence from imports. After August 2014, Russia banned food imports from a series of European Union countries and the US in reaction to the economic and political sanctions those countries had imposed. A full-scale consumer patriotism began. The former campaign “Buy Domestic!” which had always existed in the background during the 2000s, took on greater intensity. The most popular words in political discourse became “food security” and “import substitution.” Food security not only returned to the official discourse in 2014, it became the central concept of Russia’s domestic policy. Concern about the health of the population served as legitimation for the national-conservative shift in agrarian policy. It became an accepted truth that imported food was “dirty,” full of pesticides, and contained genetically modified organisms. In contrast, domestic products were “clean” and guaranteeing the health of the nation. There is an objective basis for these claims: In Russia thanks to the poverty of the farmers and the miserliness of state support, Russian farmers used one tenth the amount of fertilizers of Italy and Germany for one hectare and one hundredth that used in New Zealand.

The policy of import substitution led to a reduction in the quality of Russia’s food thanks to the efforts to produce more food on the previous resource base in order to compensate for the deficit of food caused by the limits on imports. The inability of poor consumers to pay also led to a reduction in quality. Thus, thanks to an insufficient supply of milk, about 70 percent of Russian cheeses are made from vegetable fats, which is a clear deception in what is being sold, but significantly reduced the retail price. The Russian Consumer Goods Monitor Rospotrebnadzor uncovers such violations but does not impose harsh penalties since the authorities understand that they have no alternative to import substitution. The names of products are changed in order to bring them into accordance with legal demands. As a result, instead of cheese, Russians today buy “cheese products” made on the basis of vegetable oils.

Despite the obvious reduction in consumer choice, rising prices for food, and the reduction in quality, import substitution in the food market is popular with the population. About 70 percent of the population supports the ban on food imports from the US and European Union countries, according to the Levada Center. This situation looks paradoxical unless we examine the Russian ideological context. Ideology and propaganda require looking at going to the grocery store as a civil act; in other words, the consumer is not only buying stuff, he is voting with his rubles for the right of Russia to conduct an independent foreign policy. The consumer losses are not discussed in this context since patriotism in its current form assumes a willingness to make sacrifices. When the Levada Center in 2015 asked “What are the Western countries seeking by imposing sanctions on Russia?” about 70 percent of Russians answered that they wanted to “weaken and humiliate Russia.” The pro-Kremlin media presents the image of a united people prepared for deprivations in the name of defending national interests; they also present the image of Russia surrounded by enemies which makes it difficult to change the picture of the world.

The agrarian lobby is successfully exploiting the ideologically modified attitudes of Russian consumers. For example, they actively protested Russia’s entry into the WTO by citing the opinion of the people. In fact, supporters of this step were more numerous than opponents, 30 percent to 25 percent respectively, according to data from VTsIOM in 2012. Ten years earlier, at the peak of liberal feelings, a majority (56%) supported joining the WTO, while only 17 percent were opposed.3

In conditions of “nostalgic revanchism” exploiting gastronomic memories is an effective tool for selling goods on the market. A widely used marketing technique for mass market foods has become their “Sovietizaton” when the name, packaging, and advertising reference the Soviet past. Advertising patriotism is also increasing in which the heroes of Russian folklore, examples from Russian history, fragments from Soviet films, and Soviet songs appear with increasing frequency. This Sovietization affects products that were actually available during Soviet times, such as the chocolate Alenka, and new products which are stylized as Soviet, such as the popular ice cream sold under the brand “48 kopecks.” There was no such brand in Soviet times, but an Eskimo ice cream bar cost that much and is fondly remembered by the older generation. Another example is Tushenka, a canned meat sold under the name Sovok, a slang work for Soviet, which is packaged using Soviet designs.

Ironically, the “nostalgic consumer” includes not only the older generation who remember Soviet times and have personal experience living in the USSR. Young people are also attracted to this trend, reacting to the myth and image of the times created by the collective memory of the people. It is this image of the past, cleansed of negative content that is actively used in marketing strategies. The Russian consumer, regardless of age, believes that the USSR cared about the quality of its food. Half the population of the country believes that Soviet food was of a high quality and tasted good, according to a 2014 VTsIOM poll. Buying products with a “Soviet” name, the consumer effectively makes symbolic contact with a past shorn of unhappy memories.

Conclusion

Accordingly, consumer behavior in post-Soviet Russia has made two significant transitions:

From general consumer happiness about all imported goods to a much more differentiated approach. The vast majority of Russians prefer domestic food products, but seek imported electronics and other computer and high tech products. The formation of these more sophisticated tastes was connected to the development of market mechanisms and related approaches to consumption.

• In today’s Russia, “gastronomic patriotism” defines relations between the consumer and imported goods. These feelings are driven mainly by ideological factors borne by the patriotic surge connected to Crimea. At the base of the preference for domestic foods lies an idealization of the Soviet past.

Notes

1 Sel'skoi khoziaistvo, okhota i okhotnikch'e khoziaistvo, lesovodstvo v Rossii. Statisticheskii sbornik. 2015. Moscow: Rostat, <http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2015/selhoz15.pdf> p. 38.

2 Ibid, p. 117.

3 Issledovanie VTsIOM: mneniia rossiian o Vsemirnoi torgovoi organizatsii. 2012. Tsentr gumanitarnykh tekhnologii, <http://gtmarket.ru/news/2012/08/27/4916>

Recommended Reading

- Абрамов Р. (2014). Время и пространство ностальгии // Социологический Журнал, № 4, с. 5–23.

- Барсукова С. Ю. (2010). «Экономический патриотизм» на продовольственных рынках: импортозамещение и реализация экспортного потенциала (на примере мясного рынка, рынка зерна и рынка соков) // Журнал институциональных исследований, Т. 2, № 2, с. 118–134.

- Кусимова Т., Шмидт М. (2016) Ностальгическое потребление: социологический анализ // Журнал институ-циональных исследований. Том 8, № 2. С.120–133.

- Holak S. L., Matveev A. V. and Havlena W. J. (2007). Nostalgia in post-socialist Russia: Exploring applications to advertising strategy. Journal of Business Research, vol. 60, no. 6, pp. 649–655.

- Holbrook M. B. and Schindler R. M. (2003). Nostalgic bonding: exploring the role of nostalgia in the consumption experience. J. Consum. Behav., vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 107–127.

About the Author

Svetlana Barsukova is a professor in the Department of Sociology at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow, Russia). E-mail:

Militarization of the “National Idea:” The New Interpretation of Patriotism by the Russian Authorities

By Iskender Yasaveev

Power Rhetoric

This article examines the motifs of power rhetoric concerning Russian youth and its evolution during Vladimir Putin’s third presidential term (since May 2012).1 It uses materials collected by the Centre for Youth Studies at the National Research University “Higher School for Economics” in St. Petersburg. The motifs of power rhetoric were defined as regularly encountered language con- structions in topics related to youth. The study analyzed Putin’s public speeches and recordings of his meetings with different councils concerning youth policy and other state programs. We also used the reports of the Russian Government and the Federal Agency for Youth Affairs (Rosmolodezh).

External Threat

Our analysis demonstrated that one of the key motifs of the current power rhetoric about youth is external threat. The motif of the external threat is represented by such language constructions as “struggle for minds,” “manipulation of consciousness,” “imposing of norms and values,” “the provoking of conflicts,” “informational confrontation,” “staged propaganda attacks,” and “geopolitical rivalry.” At the same time, official rhetoric does not specify who exactly is threatening Russia. The enemy remains a “figure of silence.”

Examples of how Putin uses the motif of external threat can be seen in the following excerpt:

“As demonstrated by historical experience, including our own, cultural self-awareness, spiritual and moral values, and value codes are an area of fierce competition. Sometimes, it is subject to overt informational hostility—I don’t want to say aggression, but hostility certainly—and wellorchestrated propaganda attacks. These are not irrational fears, not my imagination, this is exactly how it really is. At the very least, it is one form of competition. Attempts to influence the worldviews of entire peoples, the desire to subject them to one’s will, to impose some system of values and beliefs upon them is an absolute reality, just like the fight for mineral resources that many nations experience, including ours. We know how the distortion of national, historical and moral consciousness has led to catastrophe for entire states, to their weakness and ultimate demise, the loss of sovereignty and fratricidal wars… We must build our future on a strong foundation, and that foundation is patriotism.” (Putin, September 12, 2012)

Patriotism in this context is presented as a means of confronting this undefined, but actual, external threat.

Defense

The motif of external threat is closely linked with the motif of defense. From this perspective, young people are seen, on the one hand, as an object of protection from various kinds of “external” influences in connection with their alleged vulnerability. On the other hand, youth must provide protection, meaning that it is expected to defend the country. Official rhetoric usually combines these two different views. Along with the need to protect young people, the priorities of “protecting the country,” “protecting the interests of the Fatherland,” “securing the sovereignty of the Motherland,” and a “strong and independent Russian Federation” are emphasized.

The necessity of training young people to make them ready to defend the country is formulated as one of the priorities of the state youth policy.2 The idea of protection also dominates the new state program “Patriotic Education of Citizens of the Russian Federation for 2016–2020,”3 which highlights the issues of defense and militarization. One of the main expected results of the program for 2016–2020 is formulated as follows: “ensuring the formation among young people of moral, psychological and physical readiness for the defense of the Fatherland, loyalty to the constitution, military duty in conditions of peacetime and war time, and high civic responsibility.”

The expression “ in conditions of peacetime and wartime” was never used in the previous programs of patriotic education and is repeated in the new program two times. In this way, the Russian authorities shifted the meaning of patriotism from “love of the Motherland” to readiness to defend the state by military means from external and internal enemies. At the same time, Russian power rhetoric is characterized by the idea of patriotism as a natural and universal feature of all Russian youth: “I am sure that we all have one thing in common, and that is that we are all patriots of our country” (Putin, August 2, 2013).

Unlike the previous five-year programs for 2001–2005, 2006–2010 and 2011–2015, the adjectives “military” and “war” in different combinations such as “military- patriotic”, “military service”, “wartime”, etc. were used in the patriotic education program for 2016–2020 dozens of times. The current program suggests some innovative methods, such as using “patronage by military units over educational organizations” in which the units take the lead in providing military-patriotic education for children in civilian schools. The previous programs also suggested such “patronage” for the purposes of education, however the objects of patronage were the military units themselves and patronage implied “participation of cultural institutions, public organizations (associations), representatives of the creative intelligentsia in military- patronage work aimed at educating soldiers about the treasures of Russian and world culture.”4

Labor

In contrast to the popularity of the military-related issues, the issues of labor are almost completely neglected in the new program of patriotic education for 2016–2020. The word “labor” is used only a few times in such constructions as “Ready for labor and defense” (a sports fitness training program that existed in the Soviet Union and was restored in modern Russia in 2014 by Vladimir Putin’s decree) and “patronage of labor collectives over military units.” In contrast to the current program, all previous programs of patriotic education included statements about the preservation and development of “glorious military and labor traditions,” the involvement of labor collectives in patriotic education, “increasing social and labor activity of citizens, especially young people,” and the “development of the system of patriotic education in labor collectives.” In other words, the sphere of labor is excluded from the current patriotic education program. Patriotism is interpreted now by the authorities as being oriented primarily toward military service. The militarization of the idea of patriotism in power rhetoric constructions at the federal level is rebroadcast through dozens of programs of patriotic education in the Russian regions.

Evolving Definitions of Patriotism

During his third presidential term, Putin repeatedly called patriotism a national idea: “We have no, and cannot have any, other unifying idea except patriotism” (February 3, 2016). Meanwhile when asked about the national idea in Russia in the first half of the 2000s, Putin answered this question in a completely different way:

“The main thing is to ensure a high rate of economic growth. The future of the country hinges on that. Our country must be competitive in all spheres.” (Putin, June 5, 2003)

[Economic] Competitiveness dominated Putin’s interpretations of the main national idea:

“We must be competitive in everything. A person must be competitive, a city, a village, an industry and the whole country. This is our main national idea today.” (Putin, February 12, 2004)

The anti-traditionalism of Putin’s statements during his first term contrasts with the traditionalism of his third term. Putin has used the expression “traditional values” dozens of times over the past five years.

“We know that there are more and more people in the world who support our position on defending the traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years: the values of traditional families, real human life, including religious life, not just material existence but also spirituality, the values of humanism and global diversity.” (Putin, December 12, 2013)

The militarization of patriotism, its representation as a national idea and the displacement of the idea of the country’s competitiveness as a central notion means that the Russian authorities have abandoned the modernization aspirations that were characteristic for them in early 2000s. Becoming a “competitive country” as the goal of Russia’s development has given way to a [militarily] “strong country.”

Notes

1 The study was carried out within the project “Creative Fields of Interethnic Interaction and Youth Cultural Scenes of Russian Cities” supported by Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 15-18-00078).

2 The Foundations of State Youth Policy of Russian Federation for the Period to 2025. <http://government.ru/media/files/ceFXleNUqOU.pdf> (accessed 31 July 2017).

3 The State Program “Patriotic Education of Russian Citizens 2016–2020”. <http://government.ru/docs/21341> (accessed 31 July 2017).

4 The State Program “Patriotic Education of Russian Citizens 2006–2010”. <http://base.garant.ru/188373> (accessed 31 July 2017).

Recommended Reading

- Omelchenko, Elena. 2012. Kak nauchit' lyubit' Rodinu? Diskursivnye praktiki patrioticheskogo vospitaniya molodezhi [How to Learn to Love the Homeland?: Discursive Practices in the Patriotic Upbringing of Youth]. S chego nachinaetsya Rodina: molodezh' v labirintakh patriotizma [Where Homeland Begins: Youth in the Labyrinths of Patriotism] (eds. Elena Omelchenko, Hilary Pilkington), Ulianovsk: Ulianovsk State University, pp. 261–310.

- Yasaveev, Iskender. 2016. Leytmotivy vlastnoy ritoriki v otnoshenii rossiyskoy molodezhi [Motifs of Government Rhetoric on Youth in Russia]. The Russian Sociological Review, vol. 15, no 3, pp. 49–67. <https://sociologica.hse.ru/ en/2016-15-3/191980638.html> (accessed 31 July 2017).

- Sanina A., Migunova D., Zuev D. 2017. Patriotic education as an object of state policy: Quantitative analysis of regional programs. XVIII April International Academic Conference on Economic and Social Development at HSE. <https://events-files-bpm.hse.ru/files/_reports/86241926-EEB6-4267-8A20-00C8A314FDE7/Sanina_Migunova_ Zuev.pdf> (accessed 31 July 2017).

About the Author

Iskender Yasaveev is Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Youth Studies at the National Research University Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg.

Thumbnail external pageimagecall_made courtesy of Nicolas Raymond/Flickr. (CC BY 2.0)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.