The Islamic State´s Two-Pronged Assault on Turkey

29 Mar 2017

By Marielle Ness for Combating Terrorism Center (CTC)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCombating Terrorism Centercall_made on 15 March 2017.

“O muwahhidin! Turkey today has become a target for your operations and priority for your jihad, so seek Allah’s assistance and attack it. Turn their security into panic and their prosperity into dread, and add it to the scorching zones of your combat.” – Abu Bakr al-Husayni al-Bahhdadi1

Key Findings

- Islamic State activity in Turkey is clustered around major cities and along the country’s southern border with Syria, likely due to proximity, travel routes, and population density.

- The majority of Islamic State-linked attacks and plots in Turkey had some (formal or informal) connection back to the group in Syria and Iraq.

- The majority of attacks in major cities were conducted using explosive devices primarily delivered by suicidal means, while the plurality of attacks on the southern border utilized rockets.

- The Islamic state tends to attack soft, low-security targets in Turkish cities.

On November 4, 2016, two days after Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi instructed his followers to conduct operations against Turkey, the Islamic State claimed its first attack in Turkey. In the subsequent days, the Turkish government blamed Kurdish terrorist groups, and on November 6, the Kurdistan Freedom Falcons claimed responsibility for the attack. Despite these conflicting reports, the event marked a distinct divergence from the Islamic State’s previous policy in its approach to Turkey.

The following analysis employs an open source dataset of directly linked and conceptually inspired Islamic State attacks, plots and arrests in support2 of the organization in Turkey from June 2014 through January 2017. Since the Islamic State did not claim any even in Turkey until November 2016, Combating Terrorism Center researchers have coded events as being linked to or inspired by the Islamic State if a variety of government and media sources asserted the Islamic State was responsible or was the inspiration for an event.

Geographic Overview

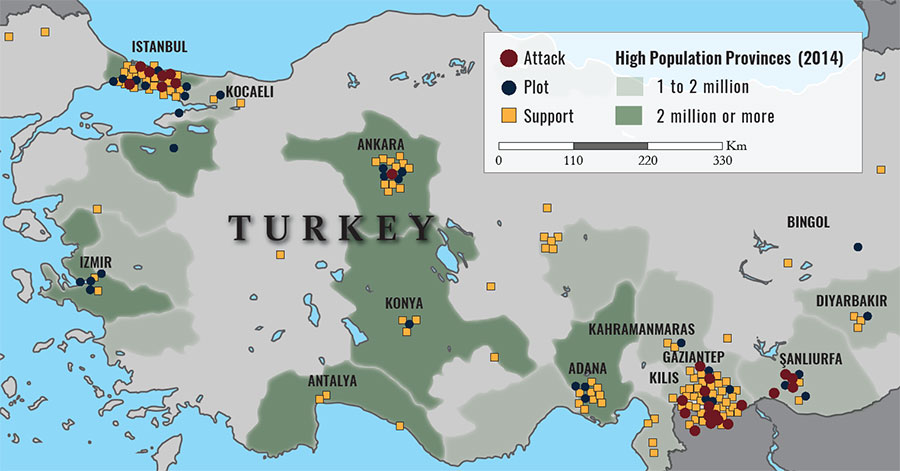

The dataset consists of 23 attacks, 28 plots, and 100 events of arrests for support activity for the Islamic State in Turkey. As the map3 (Fig 1) illustrates, Islamic State activity occurred primarily in more densely populated areas and along major travel routes. Over the dataset’s 31-month time period, 16 attacks (70%) occurred in the border region, specifically targeting Kilis and Gaziantep, while six attacks (26%) occurred around Istanbul. Attacks also occurred in Izmir, and the most lethal event happened in Ankara.

Plots4 were also concentrated in Istanbul (32%), Ankara (14%), and along Turkey’s southern border (25%). However, plots were also disrupted in Adana, Konya, Kahramanmaras, and in eastern Turkey. This divergence indicates that these regions could be focus areas for the group, the Islamic State has some level of reach—inspirational or otherwise—into these areas, or law enforcement is better equipped to manage the threat in certain cities. Support activity data paints a similar picture reinforcing Islamic State links to those locals.5

Fig. 1 Map of Islamic State Activity in Turkey June 2014-January 2017

Operational Dynamics

Connections to Islamic State Central: The overwhelming majority of attacks and plots in Turkey during the 31-month time frame were linked to the central organization of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq, whether formal or informal. Except for one plot and one attack, all were either directed by the organization or there was evidence that operatives were in direct contact with Islamic State personnel. This finding can primarily be explained by Turkey’s close proximity to Islamic State territory and that Turkey has been the primary means of entry for emigrants and foreign fighters into Syria and Iraq. What is not evident in the data is the relationship between the various Islamic State-linked operational cells in Turkey. The data indicates that the disbanding of one cell does not necessarily lead to the disruption of another cell by Turkish law enforcement.

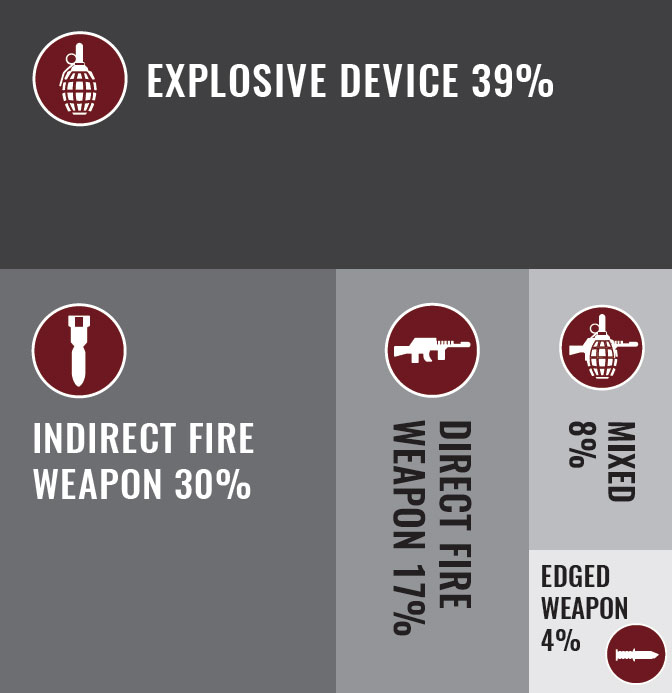

Fig. 2 Weapons Used in Islamic State Attacks

Weapons: The Islamic State relies heavily on explosive devices,6 primarily delivered through suicidal means, as a weapon for attacks in Turkey. Of the 23 attacks, nine (39%) attacks used explosive devices and six of those were delivered using either a suicide vest or vehicle. Similarly, of the 28 plots, 11 (39%) involved individuals planning to use explosive devices, 10 of which planned to deliver the weapon using suicide vests. There does not appear to be a distinct difference in weapon choice between attacks and plots. The group’s reliance on suicide bombs is not novel. For the last quarter of a century, terror organizations’ reliance on suicidal means of delivery has “proven to be one of the most efficient and least expensive tactics ever deployed.”7

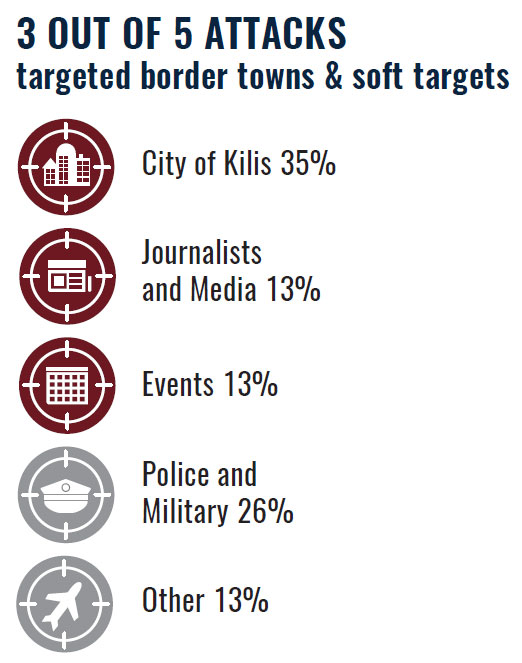

Fig 3. Target of Islamic State Attacks in Turkey

In this dataset, suicide attacks are the most lethal. These include (1) the suicide attack on a peace rally in Ankara on October 10, 2015, with 103 deaths; (2) the suicide attack on a Kurdish wedding in Gaziantep on August 20, 2016, killing 55 individuals; and (3) the suicide fighter8 attack on the Istanbul Airport on June 28, 2016, with 45 deaths.

After explosive devices, indirect fire weapons9 are the second most utilized weapon in Islamic state attacks in Turkey (30%). The majority of these attacks occurred in May 2016 in Kilis and resulted in a casualty rate of less than five causalities per attack. The Islamic State has primarily relied on Katyusha rockets for indirect fire weapon attacks.10 Insurgent and terrorist tend to resort to this weapon system rather than artillery because they can set up numerous rockets on stands to fire simultaneously without an individual present to operate them. Katyusha rockets have a maximum range of roughly 30 kilometers and offer quick effects on the target, but they are less accurate than artillery. Artillery, on the other hand, requires a crew of operators constantly firing the gun to hit the target. Use of Katyusha rockets is a classic insurgent tactic; these weapons devastate a target and leave the other party with no target upon which to fire.

Targets: Due to the small sample size of attacks and the group’s use of indirect fire weapons (which often do not have a precise or disclosed target), it is difficult to identify trends in Islamic State targets in Turkey. As a whole, the data indicates the Islamic State targets a variety of sectors and individuals. Of the 23 attacks, 35% targeted the city center of Kilis. Other main categories of attack targets—each at 13% of the total number—were events (i.e. youth activist meeting, peace rally, and wedding); journalists and media; and the military.

Although based on a small sample, the data illustrates that border towns and soft targets was a key Islamic State targeting priority, as the combination of the group’s indirect fire attacks against the border outpost of Kilis and its attacks on events, journalists, and the media account for 61% of all incidents. There appears to be no relationship between the chosen target and type of weapon employed other than the Katyusha rockets used to target Kilis. Anecdotal evidence tied to Abdulkadir Masharipov, the New Year’s Eve nightclub attacker, also suggests—that the group is flexible and responsive to on-the-ground conditions when it comes to targets. As have been widely reported, Masharipov originally planned to attack Taksim Square in Istanbul, but due to an increase in security at that location, he aborted the plan.11 He was instructed by his handler to find a new target, and ultimately selected the Reina nightclub, which he had passed earlier that evening.12

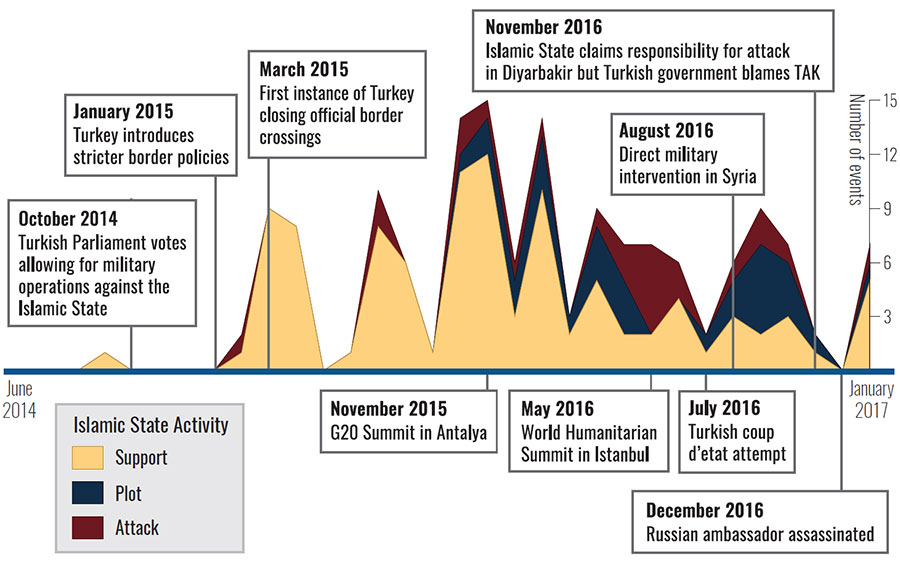

Timing Considerations: The timeline below charts attacks, plots, and support activity from June 2014 through January 2017 and denotes significant events that occurred during this time period.

During 2015, as illustrated by the timeline, there appears to be a relationship between major events and arrests for Islamic State support. This is specifically illustrated in April 2015 when Turkey closed official border crossings13 with Syria and the month leading up to and the month of G20 Summit (November 2015). This alludes to law enforcement increasing security for high-profile events and after policy changes. Furthermore, the largest number of Islamic State plots disrupted in a month by Turkish authorities (four plots) took place in September 2016, one month after Turkey’s invasion into northern Syria. Three of these four plots targeted Istanbul.

Conclusion

The data presented here illustrates the varied and dynamic threat posed by the Islamic State in Turkey. In relation to the group’s activity surrounding border towns, Turkish military forces have pushed the Islamic State farther into Syria, greatly limiting its ability to accurately use indirect fire weapons (e.g. Katyusha rockets) against the country, with the last completed attack in early October 2016. Regarding the group’s operations in major cities, law enforcement in recent weeks has increased raid, arresting hundreds of Islamic State supporters and personnel with some media sources reporting up to 750 aressts.14 However, recent investigations have highlighted the extent of the Islamic State’s network in Turkey, and increased military and law enforcement pressure is necessary to counter this threat.15

Fig. 4 Timeline of Islamic State Activity in Turkey June 2014-January 2017

Notes

1 Al-Baghdadi speech, November 2, 2016, page 6.

2 Support, as defined in this study, is any type of support an individual expresses toward the Islamic State that ends in an arrest, including but not limited to recruitment; facilitation of travel; monetary or material support; virtual support; or personnel support.

3 The geographic visualization of Islamic State activity in Turkey was constructed using geo-coordinates of events from the dataset. Only seven events did not have corresponding geo-coordinates and were, therefore, excluding from the visualization. Where there was a high concentration of events, geo-coordinates were dispersed so all would be visible.

4 Data corresponds with the location of the intended target of the plot. If individuals were arrested at a different locale, they were coded as previous support personnel.

5 Over 80% of all Islamic State arrests for support activity in Turkey was related to individuals attempting to travel to or return from Islamic State territory.

6 Explosive device is defined as anything that combusts, including but not limited to suicide vests, suicide vehicles, IEDs, and grenades.

7 Ami Pedahzur and Arie Perliger, “Introduction: Characteristics of Suicide Attacks,” in Ami Pedahzur ed., Root Causes of Suicide Terrorism: The Globalization of Martydom (New York: Routledge, 2006), p. 1

8 A suicide fighter, or inghimasi, is an individual who conducts an operation without the expectation of survival.

9 Indirect fire weapons are defined in this study as rocket artillery and mortars. Direct fire weapons are defined as small arms (e.g. AK47, handguns, pistols); shoulder-fired rocket/RPG; or crew served (e.g. machine gun, medium/heavy machine guns).

10 Aaron Stein, “ISIS and Turkey: The Rocket Threat to Kilis,” Atlantic Council, April 26, 2016.

11 “New info on ISI role in deadly Istanbul New Year’s attack,” Associated Press, January 18, 2017.

12 Ibid.

13 Despite this initial closing of official border crossings, the border was not completely shut and migration and foreign fighter flows continued over the time frame of this study. The event, however, does mark a distinct Turkish policy change and is reflected in the data.

14 “Islamic State suspects detained in Turkey raids rises to nearly 750,” Chicago Tribune, February 6, 2017.

15 Ahmet S. Yayla, “The Reina Nightclub Attack and the Islamic State Threat to Turkey,” CTC Sentinel, 10 March 2017.

About the Author

Marielle Ness is the General John P. Abizaid Research Associate at the Combating Terrorism Center.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.