Energy Security in the Baltic Region: Between Markets and Politics

13 Feb 2019

By Marc Ozawa for NATO Defense College (NDC)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageNATO Defense College (NDC)call_made on 29 January 2019. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Kremlin.ru. external page(CC BY 4.0)call_made

NATO addresses energy security concerns in three ways, through strategic awareness, infrastructure protection and energy efficiency measures. However, what may be a concern for NATO is potentially a problem for member states with conflicting views on the issue, the politics of which impact their interactions within the Alliance. Nord Stream 2, the trans-Baltic pipeline connecting Ust-Luga (Russia) to Greifswald (Germany), is one such example because it is so divisive.

This Policy Brief advocates a role for NATO as a constructive partner with the European Union (EU), the governing body for energy security issues in tandem with national governments, while avoiding the divisive politics of direct involvement. NATO and the EU have complementary perspectives on energy security. The Alliance’s view is directed at broad security implications and the EU’s Director- General for Energy (DG Energy) is more focused on market matters. In this complementarity of perspectives NATO could indirectly assist DG Energy in making better energy policies and help to avoid the politicization of projects that create friction within the EU, the type that can spill over into NATO. The strife around Nord Stream 2, for example, works against both EU unity and cohesion within NATO such that, what may not have originally been perceived as a problem for NATO, becomes one.

In the near term, it is difficult to imagine a unified view of Nord Stream 2 emerging within the EU, or amongst NATO member states. Proponents of the project (mainly in Western and Southern Europe) advocate market benefits while opponents decry the threat it poses to Ukraine not to mention those states that border Russia given their high dependence on Russian energy. With respect to Ukraine, Nord Stream 2 effectively removes the need for Ukrainian pipelines and further squeezes an already deteriorating negotiations position.

Tensions in Ukraine

Over the past decade, every time Ukraine’s negotiations position has diminished, the conflicts with Russia have become more acute and violent. Although NATO member states in the Baltic Region may today be more resilient to a supply disruption than previously, some states might not stand by idly in the event of another energy debacle in Ukraine. Because varying European views are predicated on different assumptions about the role of energy in international relations, it is difficult, if not impossible, to reconcile them in the current politically-charged climate. In order to help reduce tensions, improving strategic awareness through information exchanges between the EU and NATO is important given their complementary market-relative-to-security perspectives.

Likewise, increased information sharing and consultations among stakeholder groups are needed. States in the region would benefit from preparing now for a pro-active rather than re-active response to this year’s natural gas negotiations between Ukraine and Russia when the contracts currently in place will expire. The recent clash between Ukrainian and Russian forces in the Sea of Azov underscores the deteriorating situation. Considering that the last negotiations were part of drumroll of events escalating to the Russia-Ukraine crisis, the need for inter-organizational communication is critical to avoid “sleepwalking” into a geopolitical catastrophe that could draw in NATO member states, perhaps not militarily but destabilizing the Eastern Flank nonetheless.

Perspectives on energy security

A useful tool in understanding the competing tradeoffs facing policy makers is what is known as the “energy trilemma”. This framework illustrates the three primary components of energy policy including security of supply, the environment, and economics (or markets and social welfare).

The primary concern for NATO is the supply component. For supplier states such as Russia, the most important dimension is access whereas importing states in Europe emphasize access to supply.

For some states in the Baltic Region, the issue of energy dependence on Russia is an ongoing national security concern. Edward Lucas was one of the first western observers to warn against the prospect of a “new Cold War”, one that is divided not along ideological lines but rather characterized by Russia as one of several regional powers in a multipolar world. According to this perspective, Russia is pitted against Europe, NATO and the states that have traditionally comprised “the West including Japan” with energy representing one of the pressure points through which countries may exert influence.1 This is a world in which energy trade is less driven by commercial than political actors. Another observer claims that we have reached, and have perhaps even passed, a tipping point whereby global energy trade is being driven not by economic forces so much as hard power.2

These are two quite stark views of the status quo. A more mainstream and perhaps optimistic view of current events would be that we are witnessing the transition pains of a global system that is shifting from a unipolar, Pax Americana, to a new multipolar reality and that this shift will be neither linear nor smooth. Although the aim here is not to make sweeping claims about the energy world, it is important to mention these views because they represent narratives that are often associated with the geopolitics of energy.

Regional energy relations with Russia

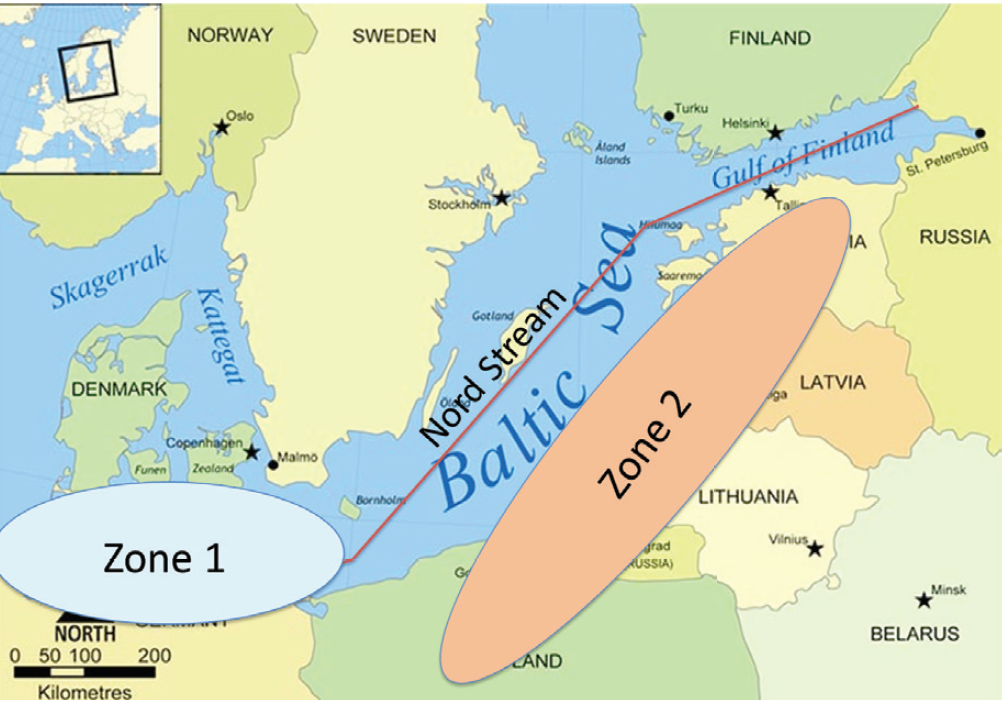

The Baltic Region is here defined as comprising the littoral states of the Baltic Sea, in contrast to what is sometimes referred to as the “Baltic states” of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Hence this analysis also takes into account Finland, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Poland, and of course Russia. In the Baltic Region, energy, in the form of oil and natural gas, generally flows from east to west, from Russia (the supplier) to the energy markets in the west. For historical reasons, namely the experience of World War II and the Cold War, the countries that were formerly Warsaw Pact countries and part of the Soviet Union (labelled Zone 2 in the below Figure 1), are more concerned with energy dependence on Russia than those that were NATO member states prior to 1991 (labelled Zone 1).

Figure 1: Fractured Baltic Energy Markets

This concern is not without merit. On the one hand, their level of dependence on one single supplier is simply higher. As Winston Churchill pointed out, “security in oil lies in variety and variety alone.”3 The second reason is that their experience with Russia as a supplier has been contentious compared to West European countries whose policy makers often praise the reliability of Russian energy supplies, even during the height of the Cold War and the ‘chaotic 1990s’. Russia’s Baltic neighbors have experienced multiple supply disruptions and disputes.4

As Russia’s neighbors, leaders from eastern Baltic States often complain about the different treatment they receive from Russia compared to Western Europe, claiming that Russia uses energy as a political tool for exerting infl uence on the region. For these states, Russia is perceived as an existential threat that is difficult to appreciate from the outside. As a result some eastern Baltic states have sought to reduce their dependence on Russian energy supplies, their concerns affirmed by experiences of states in the Black Sea, Caucasus and Balkan regions. The aggregate effect of these new infrastructure projects has been the fracturing of the Baltic Region into two energy security zones defined not only by physical constraints (availability of supply and other market characteristics) but also historical rivalries.

The shift in behavior and tone of interactions with Russia as one moves eastward across the southern Baltic region changes from cooperative to more adversarial. A number of factors contribute to this transition ranging from history and culture to interests and threat perceptions. Cooperation between Russia and western Baltic actors are reflected by signed agreements, visits and fulfilled contractual obligations. On the other hand, conflict between Russia and some eastern Baltic neighbors may come in the form of broken contracts, disputes, and commercial boycotts. The signals that each side sends to the other have shaped how actors interpret one another’s actions and what the appropriate reaction should be. This partially explains why interactions between Zones 1 and 2 with Russia are so varied and why the perspectives on Nord Stream are hard to reconcile.

Regional geopolitics and infrastructure developments

The geopolitical context to the east has also stoked new fears about energy trade with Russia. One major factor was the 2014 Russia-Ukraine crisis leading to the annexation of Crimea and another, the Russo-Georgian War of 2008.

Accordingly states in the Baltic Region have sought to either find alternative energy supplies to Russia, in the case of Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland and Finland, or to build new pipelines thereby bypassing Ukraine, in the case of Germany and Russia. This has had both stabilizing and destabilizing effects. New infrastructure for supplanting Russian supplies includes the construction of two liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminals in Świnoujście, Poland, and a floating facility off the coast of Klaipėda, Lithuania. These states have also invested in natural gas storage capacity and reverse-flow compressor stations, which allow gas to flow west to east (rather than only east to west). Additionally pipeline and electricity network operators in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland are coordinating to better distribute energy supplies in the region in case of a supply disruption.

New electricity transmission interconnectors are also being constructed to better link the eastern Baltic grid to Finland and Sweden. Another major development is a new nuclear power plant in Finland. Once complete, the Olkiluoto 3 project will have the potential to supply up to 10 percent of total Finnish power demand.5 Although these states have become more resilient to a Russian supply disruption, other developments have had a countering effect.

From a negotiations stand point, the states between Russia and Germany have historically maintained a degree of leverage over Russia for transporting natural gas to Western Europe. As Figure 2 illustrates, Nord Stream 1 supplanted approximately one third of the total natural gas flows from Russia to Europe when it became operational in 2011.6

Figure 2: Russia’s Dependence on Ukraine Pipeline for European Exports

Nord Stream 2, which is currently under construction, simply reinforces this trend by continuing to reduce Russia’s dependence on Ukraine. The capacity of Nord Stream 1 was 55 billion cubic meters (bcm) per annum whereby Nord Stream 2 would double that and overtake the current levels of 70-80 bcm being transported through Ukrainian pipelines.

NATO and energy security

Although energy security falls under the jurisdiction of national governments, a look at NATO’s range of energy-related activities reveals a more nuanced view.7 There is a NATO Centre of Excellence devoted to the study of energy security, and since the 2008 Summit in Bucharest, the Alliance has adopted the concept of “Energy Security” as one of a range of subjects that it addresses.

NATO engages energy security in three ways. The first is through, what NATO calls “Strategic Awareness” by keeping informed of the relevant issues and sharing information among member states The second is through supporting the protection of critical infrastructure. Lastly, the Alliance promotes energy efficiency in the military, thereby contributing to the energy security of NATO’s activities.8

Historically NATO has, albeit perhaps reluctantly, played a more active role as one of the international fora where member states have deliberated on energy security matters. The clearest example of this was the Large-Diameter Pipe Embargo of 1962, which was initiated by the US and shaped through debates in NATO.9 The embargo was intended to prevent the Soviet Union from building the infrastructure that would enable oil and gas exports to Western Europe. Two decades later, the US led a second sanctioning of pipeline-related materials to the Soviet Union. However, this time NATO member states were divided on the issue and ultimately the Alliance never signed on to the sanctions. As things stand today with Nord Stream 2, NATO’s role is limited to information sharing and consultations whereas member states, along with a growing EU role, are responsible for regulation and energy policy matters.

EU-NATO interactions and reinforcing regional stability

Compared to Russia, where the point of contact for gas negotiations is simple, usually Gazprom, there are several groups on the European side including national governments, companies, the EU (meaning the Commission), unions and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The interests of states, be they commercial or strategic, are still important and will usually drive developments, but in the long term greater interaction will help to build social capital and improve the coherence of positions among the various stakeholders. And with greater alignment of perspectives, we can expect to lower the probability that one or more actors may unintentionally create a security problem for all parties. Raising awareness of the various aspects of energy security through information sharing and repeated interactions is an important, yet deceptively simple first step towards building the trust and cohesion among the various actors in the Baltic Region and the eastern neighborhood.

Although energy security is included in the Third Energy Package and the emerging “Energy Union”, EU policy is commercially rather than security driven. Given the supply disruptions of the past decade, military conflicts in Ukraine and Georgia and Gazprom’s status as a state-owned entity, it should come as no surprise if and when politics may become intertwined with the business of energy in the border regions of Russia. Long-time observers of Russia will recognize the fluid relation between commerce and politics.

In contrast to the EU, on energy matters NATO is limited to building strategic awareness/information sharing, protecting critical infrastructure and contributing to greater efficiency for its facilities and operations. However, since the joint declaration between the President of the European Commission (EC) and the Secretary General of NATO in 2016, both organizations are making efforts for the “enhancement of the EU-NATO relationship” and “EU-NATO cooperation”. Although energy security is not mentioned in the list of cooperation areas, greater interaction between NATO and the EU presents opportunities for improving the strategic awareness of both organizations and thereby better informing the energy security policy-making process within the EC. With respect to energy security, interactions have already begun ranging from joint EU-NATO exercises and informal North Atlantic Council sessions to staff-to-staff talks and EU participation in thematic meetings and courses, to name but a few. These are encouraging first steps, and perhaps more important is the potential for further substantive cooperation in the future as institutional links develop.

Notes

1 E. Lucas, The new Cold War: how the Kremlin menaces both Russia and the West, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2009.

2 J. Verbeurgt, “The geopolitics of energy: energy security in the 21st century”, European Security and Defence, 06/2018, p. 14.

3 Originally cited in D. Yergin, “Ensuring energy security”, Foreign Affairs, Vol. 85, No. 2, March 2006, pp. 69-82.

4 See R. L. Larsson, Russia’s energy policy: security dimensions and Russia’s reliability as an energy supplier, Stockholm, Swedish Defence Research Agency (FOI), 2006.

5 “Areva’s Finland reactor faces new delay”, Reuters, 13 June 2018.

6 C. K. Chyong, “The role of natural gas in Ukraine’s economy and politics”, Energy Policy Research Group, University of Cambridge, Presentation of EPRG E&E Seminar, 26 May 2014.

7 J. Grubliauskas and M. Rühle, “Energy security: a critical concern for Allies and partners”, NATO Review, July 2018.

8 J. Grubliauskas, “NATO’s energy security agenda”, NATO Review, 2014.

9 A. E. Stent, From embargo to Ostpolitik: the political economy of West German-Soviet relations, 1955-1980, Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 114-5.

About the Author

Marc Ozawa is a Visiting Scholar in the Research Division at the NATO Defense College.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.