Never Again: International Intervention in Bosnia and Herzegovina

16 Aug 2017

By David Harland for Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageCentre for Humanitarian Dialogue (HD Centre)call_made in July 2017.1

Executive summary

The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina was the most violent of the conflicts which accompanied the break-up of Yugoslavia, and this paper explores international engagement with that war, including the process that led to the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement. Sarajevo and Srebrenica remain iconic symbols of international failure to prevent and end violent conflict, even in a small country in Europe. They are seen as monuments to the "humiliation" of Europe and the UN and the failure of UNPROFOR, the peacekeeping force on the ground.3 On the other hand, the 1995 military intervention, the Dayton agreement, and the NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR) are seen as redemptive examples of the potential of military intervention under American leadership.4

These perceptions have subsequently shaped Western approaches to military intervention for a generation, and have informed the doctrines of "humanitarian intervention" and the "responsibility to protect".5 Yet this paper argues that these perceptions, based on an inaccurate narrative of the conflict, are wrong, and therefore the basis on which other interventions have subsequently taken place – including in post-war Bosnia and Iraq, Libya and elsewhere – are fundamentally flawed.6

A flawed elite deal?

The political deal that ended the war in Bosnia had been in preparation since before the fighting began, and evolved slowly over the three-and-a-half years. The Dayton agreement was the fifth iteration of this deal. The main features of the Dayton agreement had been elaborated in the four earlier plans. What was distinctive about the Dayton deal was that it took on many of the worst features of the earlier plans and discarded some of the best.

The Dayton agreement was an elite deal between the same three ethno-national elites that had started the war in the first place, and was brokered by the US without the endorsement of the people whose fate it determined. It cemented a ceasefire that had already been put in place by the UN before the negotiations began, and confirmed the results of ethnic cleansing, mainly to the benefit of the Serbs. Quite unnecessarily, it created enduring constitutional arrangements which were both unworkable and discriminatory, and which have prevented the emergence of moderate and pragmatic political forces.

The role of international actors

International responses to the crisis in Yugoslavia were generally reactive and incoherent. European states acted at cross-purposes with one another, and Europe acted at cross-purposes with the US. International organisations, such as the UN and NATO, were given conflicting mandates and undermined one another. Even when they were able to act together, the tools at the disposal of the international community were poorly coordinated. The lever of recognition was squandered by differences between Germany and its European partners. The Lisbon Agreement, which might have prevented the war altogether might have been fatally undermined by negative American signals, as was the Vance-Owen plan. The UN peacekeeping force was undermined by contradictions between those who provided troops but wanted a limited mandate and those who wanted a robust mandate but wouldn’t provide troops. And military intervention, when it happened, was disconnected from efforts to find a political settlement.

This paper asserts, therefore, that the war in Bosnia did not end because of a successful US-led humanitarian intervention; that the Dayton agreement is nothing to be emulated in the way it was brokered, in its content, or in how it was implemented; and that IFOR was less successful than UNPROFOR, and contributed to Bosnia’s continuing dysfunction. The war ended when it did for three main reasons. First, Europe and the US overcame the differences and mixed signals that had undermined their efforts until that point. Second, military events on the ground, led by Croatia, convinced the Serbs that they were on the brink of defeat and needed a settlement. And third, UNPROFOR was able to create the conditions for Western intervention and a durable ceasefire.

The lesson from this is not that the military intervention in 1995 was wrong, or that it would have been better not to attempt to broker a deal. On the contrary, the intervention was the right thing to do. What is important is to understand that it was not as decisive as later accounts have claimed; and the deal that emerged was not as positive.

Ultimately, this case points to the fact that foreign intervention in conflicts is fraught with cost and risk, even when the resources are enormous, the place is small, the sides are exhausted and the solution is largely agreed by local actors, neighbouring countries, foreign sponsors, and the world's most powerful nations. Even in these circumstances, failure in Bosnia was possible, and what success there was relied on time, luck, will and unusually capable military command, none of which can be relied upon to be present in any other situation.

The durability of the deal?

More than two decades after the deal, there have been no further outbreaks of fighting. The ceasefire that UNPROFOR oversaw prior to Dayton is still in effect and has never been violated. However, essential flaws in this elite bargain mean that Bosnia remains a dysfunctional state trapped in the provisions of that agreement. It is one of the poorest countries in Europe; the machinery of government established at Dayton is cumbersome and remains unreformed and financed by unsustainable levels of debt; school curriculum and the media reinforce grievances and fears among communities; rates of divorce and depression are high; and the rate of recruitment to jihadi organisations is the highest in the world. There might not have been a return to war, but there has been minimal progressive change.

Part I: The origins of the conflict

Four wars led to the collapse of Yugoslavia: Slovenia (1991), Croatia (1991-1995), Bosnia (1992-1995), and Kosovo (1998-1999). Of these, the war in Bosnia was by far the bloodiest, with three times as many killed as in all the others combined.7

Yugoslavia emerged in the early 20th century from the wreckage of the multi-ethnic Hapsburg and Ottoman empires. Like other new countries in Eastern Europe, Yugoslavia was ill-suited to existence as a nation state. Not only was it comprised of numerous self-identifying ethno-religious communities, but these communities were often inter-mingled. For almost the whole of its history, it was troubled by “the national question”.

During its first decades, Yugoslavia was roiled by conflict between Orthodox Serbs and Catholic Croats. This was amplified during World War 2, when the country was partitioned, with much of what is now Croatia and Bosnia being ruled by the pro-Nazi Croatian Ustaša. Under Ustaša rule, camps were set up to exterminate Serbs, Jews, Roma and others. SS Divisions were raised, including from among the Bosnian Muslims. Omni-directional inter-communal violence was common, with all communities being the victims of massacres. In all, more than a million people died, with Serbs accounting for the largest share of the victims.

Yugoslavia recovered, however, under the communist leader Josip Broz Tito. During the war, Tito's Partizan movement had provided inspiration to proponents of the Yugoslav idea, particularly in Bosnia, which had been the main battleground. Although initially made up mainly of Serbs from areas controlled by pro-Nazi forces, the Partizan movement was ideologically multi-ethnic – Tito himself was of Croat and Slovene heritage, and his commanders (and wives) were drawn from a range of communities. Yugoslavia's post-war economic performance and geo-political independence also became a source of pride for people of all communities.

With Tito's death in 1980, however, the country began to slip into crisis. Yugoslavia, which had one of the world's fastest-growing economies in the 1950s and 1960s, stagnated in the 1970s and went into precipitous decline in the 1980s. The country's geo-strategic position had guaranteed it easy credit from the West during the Cold War, but that faded with East-West détente and real income per capita fell by almost half in the decade following Tito's death.8

The economic crisis was accompanied by a political crisis. The post-Tito political leadership was weak, and the 1974 Constitution enshrined a system of power sharing, and of checks and balances, that hampered effective leadership. Partly under pressure from abroad, political space was opening, and was being filled by nationalists, including Serbian strongman Slobodan Milošević in Serbia, Franjo Tudjman in Croatia, and others.9

The nationalist agenda was straight-forward: they wanted independence, or maximum autonomy, for administrative units in which their community would be in the majority, and therefore politically dominant. This formula was easiest to apply in the case of Slovenia, as almost all Slovenes lived in the Republic of Slovenia, and few non-Slovenes lived there. In all other cases, however, the situation was more complicated, and nationalist goals could not be accommodated without either moving borders, or moving – or killing – people.

The communists had divided Yugoslavia into six nominally autonomous republics – Bosnia, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia and Slovenia. Partly by design and partly by the accident of demography, all of the republics except Slovenia were ethnically mixed. Croatia had a large Croat majority but a significant Serb minority; Serbia had a large Serb majority but two million Serbs lived outside of Serbia; and Serbia's "autonomous province" of Kosovo was home to an overwhelming Albanian majority of almost two million. Macedonia and Montenegro had Macedonian and Montenegrin majorities, but were also home to Albanians, Muslims, Serbs and others and Bosnia had no majority community.

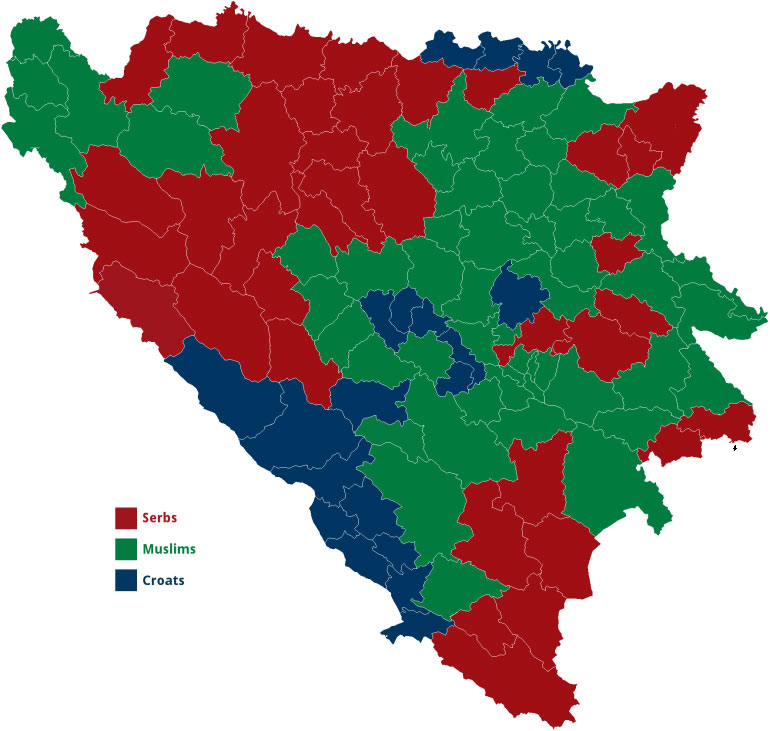

Ethnic Distribution in Former Yugoslavia

This complexity ensured that the borders of the six republics would be contentious if ever the country broke apart, as identity was mostly with the community (Serb, Croat, Muslim, etc.) and much less with the republic (Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia, etc.). Moreover, nationalists in Serbia and Croatia aspired to a "Greater Serbia" or "Greater Croatia", in which Serb- and Croat-inhabited territories outside the eponymous republic might be joined to the national home. Bosnia, with its large populations of Serbs and Croats, was a natural target of these ambitions.10

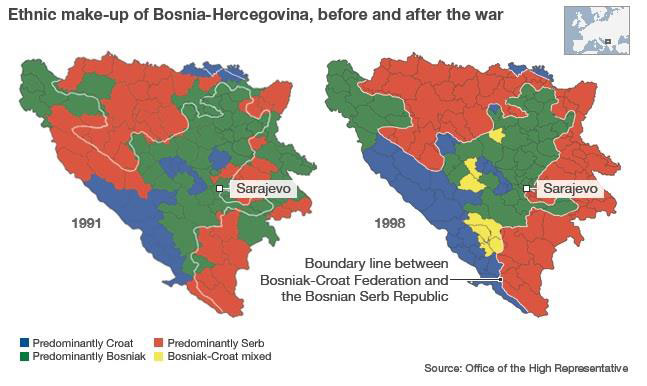

On the eve of the war, Bosnia's population was 43% Muslim, 31% Serb and 17% Croat. People without strong national affiliation – sometimes identifying themselves as “Yugoslavs”, and often from mixed marriages – and members of smaller communities, made up the rest. The differences between the communities were, and are, small: there are no significant differences of language or appearance, and a Bosnian of one community can often not identify the community to which another Bosnian belongs. Even socio-economic differences were small. Inter-marriage among the communities was common in the communist period, particularly in the cities. The level of hostility between the communities has baffled some observers, and has sometimes been described with reference to Freud's observations on “the narcissism of minor differences.”11

Nationalists defeat communists in free elections

Yugoslavia’s communist leaders agreed to hold the country’s first free elections in 1990. Bosnians organised themselves into three main nationalist parties, whose leaders were supremely unqualified to bridge the differences between the communities. Muslims rallied to the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), led by Alija Izetbegović, who had been jailed by the communists for his intent “to build an Islamic State in Bosnia”, and whose Islamic Declaration stated that there can be “no peace or coexistence between the Islamic faith and non-Islamic social and political institutions.” Serbs rallied to the Serb Democratic Party (SDS), led by Radovan Karadžić, a neuro-psychiatrist and poet who was to be later convicted of genocide. Croats rallied to the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), many of whose members took on the symbols – and sometimes the policies – of the Nazi period.12

Despite their clearly incompatible goals, these three parties formed an electoral alliance. With one another's support, the communists were defeated, as they were in Yugoslavia’s other republics. Roughly 75% of each of Bosnia’s largest communities voted for the three main nationalist parties, which took all seven seats of Bosnia’s collective presidency – three for the Muslim SDA, two for Serb SDS, and two for the Croat HDZ – and dominated the national and local assemblies.

At this point, the situation might still have been salvaged. Izetbegović had been beaten into second place by Fikret Abdić, a chicken tycoon from western Bosnia. Abdić had run with the SDA, but was neither an Islamist nor even much a nationalist – he had done well with old communist elites, and believed that a similar set of cosy accommodations could be found among the new nationalist elites. But Abdić was out of step with the Muslim nationalist establishment, which came to see him as a traitor to the cause. He stepped aside, withdrawing to a small castle on a hill in his home town of Velika Kladuša, hated by the emerging Muslim elite but adored by local poultrymen. The institutions in Sarajevo were taken over by more committed nationalists from the three winning parties.

Representatives of moderate parties were also successfully sidelined. The approximately 20% of the population who had voted against the nationalists were mainly from the urban middle classes, of all ethno-religious backgrounds. If the nationalist parties had been divided, the non-nationalists would have at least been swing players. But the nationalists held together for long enough to consolidate control of all state institutions, and then, as widely predicted, turned on one another. Thereafter, Bosnia became ungovernable, and, a little over a year later, slid into war.13

War in Slovenia and Croatia, and the “hour of Europe”

Slovenia declared independence in June 1991, just a few months after the first free elections, soon followed by Croatia. Slovenia, with its uniquely uncontentious borders, escaped almost unscathed after just ten days of confrontation and skirmishing with the Serb-dominated Yugoslav army. Croatia, however, descended into open warfare, with Serb nationalist forces seizing much of the Serb-dominated hinterland, and killing and expelling Croats as they did so in what became known as “ethnic cleansing”.

Until this point, the world beyond Yugoslavia had mostly tried to avoid getting involved in the country's troubles. Yugoslavia’s problems seemed complicated and atavistic, and not important enough when compared to other events at the time. European communism had collapsed; the Soviet Union was breaking up; Germany was re-uniting; and a military coalition was being built to repel Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. More prosaically, but also absorbing diplomatic energy, Europe's diplomats were in the middle of the negotiations that would lead to the Maastricht Treaty, which transformed the European Community into the European Union and created the euro.14

Moreover, the major European and other powers held opposing views as to how to deal with these events. Unhelpfully, these views in some ways mirrored the positions taken in World War 2. France and the UK, along with Russia, generally supported efforts to keep the country together and thus appeared sympathetic to the Serbs, who were the largest community and politically dominant. Germany, Austria and Hungary opposed the Serbs and supported the Croats and Slovenes, as they had for a century, proposing full, early recognition of Croatia and other breakaway republics. Turkey was supportive of the Bosnian Muslims, in cooperation with whom they had ruled Bosnia for centuries. The United States initially leaned closer to the position of France and the UK, with Secretary of State James Baker stating that the United States would not recognise Slovenia or Croatia “under any circumstances”, and that it had “no dog in this fight.”15

Despite their differences, the European Community responded quickly to the fighting in Slovenia and in Croatia. A mediation troika was established, and brokered an agreement on the Adriatic island of Brioni. This put an end to the fighting in Slovenia, and led Jacques Poos of Luxemburg, then at the helm of the rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union, to announce, with what came to regarded as exquisitely bad timing, that “the hour of Europe has dawned.”16

Buoyed by initial success, the European Community plunged in further, and two inter-linked mechanisms were established. The first was the International Conference on the Former Yugoslavia (ICFY), chaired by Lord Peter Carrington. ICFY's London Peace Conference took place in August 1991, with Carrington proposing Arrangements for a General Settlement which envisaged keeping the country together under a "loose confederation". These failed, largely over objections from Milošević, who wanted to retain more of the Serb-dominated centralised state.17

The European Community also established the Arbitration Commission, convened under the leadership of French jurist Robert Badinter. Following the failure of the International Conference, the Badinter Commission opined that Yugoslavia was “in the process of dissolution”, and, later, that the boundaries of the six Yugoslav republics would “become frontiers protected by international law.” In other words, subject to specified criteria, the European Community would recognise individual Yugoslav republics, within their current administrative boundaries, as they seceded.18

These initiatives were not a success, and, between them, sent dangerously mixed messages to the protagonists on the ground. Slovenia and Croatia understood that independence on their preferred terms was a real possibility. The Serbs saw how much they would lose if the country were allowed to break apart: the two million Serbs outside of Serbia would instantly become minorities in someone else's new nationalist state. But the Serbs also saw that there was division over the recognition issue, that there was no appetite to intervene against them, and that, as the party holding most of the weapons, their hand had been strengthened by the imposition by UN Security Council of an arms embargo.19

Germany then broke ranks with the Community by announcing its intention to recognise Slovenia and Croatia, irrespective of whether the latter had met the criteria established by the Badinter Commission.20 Carrington was opposed, arguing that this “might well be the spark that set Bosnia-Herzegovina alight,” and that a decision to recognize Croatia and Slovenia robbed the mediators of “real leverage”. Despite these misgivings, the Community fell in line with Germany.21

An uneasy – and what turned out to be temporary – peace was established in Croatia, requiring the Serbs to withdraw some of their men and weapons, many of which were just moved over the border to Bosnia.

The Carrington-Cutileiro Plan: mixed signals and war

As fighting intensified in Croatia, and with Bosnia on the edge, the Badinter Commission issued another opinion, noting that the issue of the recognition of Bosnia still needed to be ascertained, “possibly by means of a referendum.”22 This prompted a round of competitive referendums. Bosnia’s Serbs organised a first vote in November, affirming their intention to remain a part of what was left of Yugoslavia.23 On 9 January 1992, they declared the establishment a Bosnian Serb “Republic”, to become independent of Bosnia if Bosnia attempted to become independent of Yugoslavia. Bosnia's Muslims and Croats then began to organise a referendum for Bosnia as a whole, knowing that their combined populations would ensure a majority for those seeking to separate from Yugoslavia. The referendum took place on 29 February and 1 March 1992. Muslims and Croats voted overwhelmingly for independence; Serbs boycotted.

Sporadic killings began even before the referendum was over. A Serb civilian – a guest at a wedding in Sarajevo's Old Town -– was shot dead as he waved a Serbian flag. Bosnian Serb preparations for war intensified, with help from Serbia, and also from Serbs forces and equipment being pulled back from Croatia. Masked men erected barricades in Sarajevo; Yugoslav military units clashed with Croats in Herzegovina; and Serb paramilitaries killed civilians in Bijeljina near the border with Serbia.

As the situation on the ground unravelled, the Europeans convened a peace conference chaired by Portuguese diplomat José Cutileiro, which appeared to make progress. The Carrington-Cutileiro Peace Plan established the basic model for the four peace proposals that followed. It was a "consociational" proposal: Bosnia would be independent, without changes to its borders; the country would be divided into "cantons", each dominated by one or other of the ethno-religious communities; and there would be power sharing between the three communities through a weak central government.24

The Carrington-Cutileiro Plan was signed by the leaders of all three communities in Lisbon on 18 March 1992. Under this Lisbon Agreement the 109 municipalities of Bosnia were to be allocated to one or other of the three communities. The mediators stated that the apportionment would be “based on national principles and taking into account economic, geographic, and other criteria,” but the preliminary proposals largely followed the results of the recently concluded census. The Muslim and Serb cantons would each have covered 44% of the territory, with the Croat canton covering the remaining 12%, to the distress of the leadership of that community.25

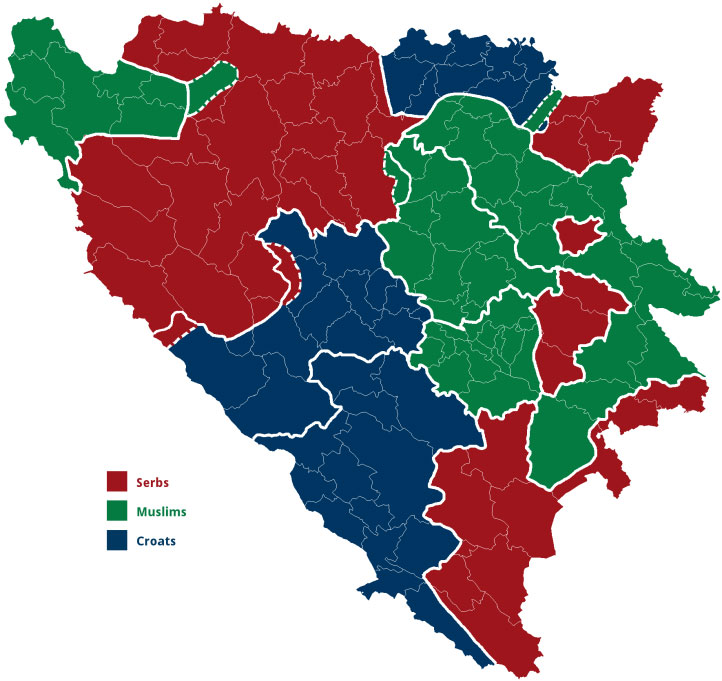

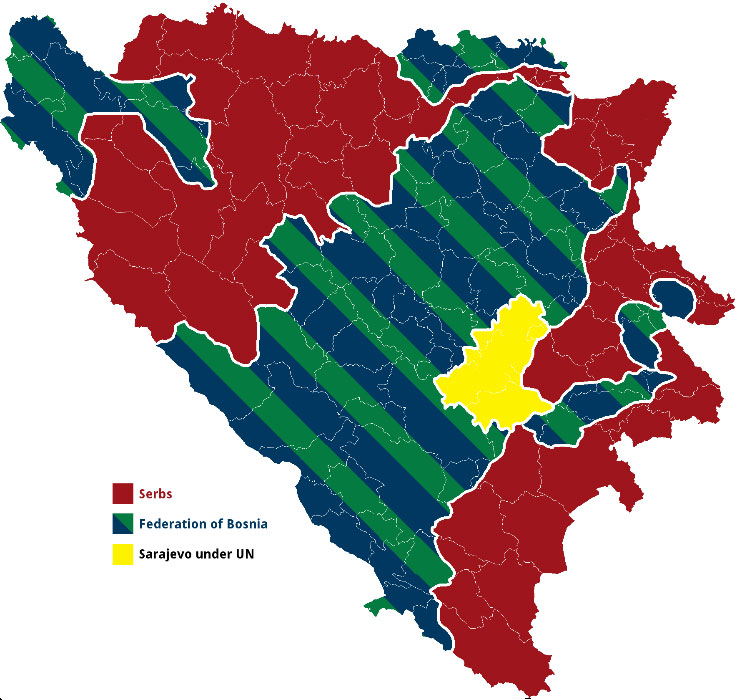

Carrington-Cutileiro Peace Plan, March 1992

The deal collapsed, however, before it could be fully developed and implemented, when President Izetbegović withdrew his signature. The reasons for this remain disputed. Izetbegović met with US Ambassador Warren Zimmerman on his return to Sarajevo, before announcing, on 28 March, that he was now opposed to the plan he had signed just over a week earlier and to any “division of Bosnia.”

While Zimmerman has denied that he advised Izetbegović to withdraw his signature, or that he gave assurances that the US would recognise Bosnia irrespective of whether an agreement was in place, what is not disputed is that the Muslims would never again be offered as much, and would ultimately settle at Dayton for much less.26

In the absence of an agreement as to whether Bosnia should be independent, stay part of Yugoslavia, or be divided – and in the absence of a generally accepted mechanism for even considering these issues – violence intensified. As Bosnia began to separate from what was left of Yugoslavia without Serb consent, Bosnia’s Serbs tried, as threatened, to separate from Bosnia. The European Community and the United States recognised Bosnia's independence at the beginning of April 1992, just as the fighting on the ground tipped into full-scale warfare.

The protagonists and how they fought

The war in Bosnia lasted from March/April 1992 to October 1995, and involved three main actors: the internationally recognised, Muslim-dominated Government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina; Republika Srpska, with its headquarters in Pale, near Sarajevo; and the Croat Republic of Herceg-Bosna.

The Government of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina

Izetbegović's core constituency was Muslim nationalists – those who had voted for the SDA in the 1990 election. Once the war began, however, several other groups became key to the government's survival. Many of the brigades were led by gangsters and petty criminals, Muslim by heritage but often with no strong political or religious agenda, who defended Sarajevo until late 1993.27 An ethnically diverse, and often political liberal, urban civilian population also offered varying degrees of support to the government, as an alternative to the nationalist extremism on offer from the Serb and Croat establishments. A small number of former Yugoslav military officers of Serb and Croat heritage also rallied to the government’s aid for the same reasons, and were useful to the government, at least as a signal to the West of its claimed commitment to multi-ethnicity.28

At the international level, Sarajevo enjoyed even more heterogeneous international support, including the US and the Western liberal establishment, and the Islamic world, including Shi'a Iran, the main Sunni states, and the jihadi networks. It was a difficult coalition to manage, requiring a moderate and multi-ethnic face for the West, and an Islamist – or at least Muslim – one for the East.

Republika Srpska

The leadership of Republika Srpska based itself in Pale, a mountain village near Sarajevo, unremarkable other than as the location of Karadžić's weekend cottage. The Pale civilian leadership was dominated by educated, if sometimes apparently unhinged, urban intellectuals, including a psychiatrist, a biologist, and a professor of comparative literature with an apposite Shakespeare quote for every occasion. This group of leaders sought, with considerable success, to awaken historic Serb fears of oppression and extermination. Karadžić, in particular, was a master of “post-truth” politics, spinning fictions – such as of the Muslims shelling their own civilians at the Sarajevo market place in 1995 – which endure to this day.29

The Bosnian Serbs had a complicated relationship with Serbia’s Milošević. Both were nationalists, though Milošević’s nationalism seems to have derived more from opportunism than from conviction. For reasons mainly related to internal Serb politics, Milošević encouraged the Bosnian and Croatian Serbs in their original efforts to establish Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Republika Srpska Krajina in Croatia. Also for reasons to do with Serb internal politics, however, and later also because of international sanctions, Belgrade’s support was never decisive, and was eventually withdrawn from Croatian Serbs almost together.

Belgrade thus pretended to be neutral in Bosnia, and withdrew the Yugoslav army as fighting intensified. In fact, however, the Yugoslav army was dominated by Serbs, and much of its equipment in Bosnia was handed over to the new Army of Republika Srpska (VRS), and Belgrade continued to provide clandestine support to the VRS throughout the war – intelligence, weapons, ammunition, fuel, payroll, spare parts, and maintenance. However, formed units were not provided, and what was provided was never quite sufficient to force a military result on the battlefield.30

Until the tide turned in the summer of 1995, the VRS, under the command of General Ratko Mladić, was by far the most effective fighting force in Bosnia. Although outnumbered more than two-to-one by the Muslims and Croats, a force of approximately 100,000 Serb men controlled most of the country for much of the war, and terrorised much of the rest.

The Croat Republic of Herceg-Bosna

The Bosnian Croats, led by Mate Boban, were the smallest of the three communities, and were divided between those living in almost purely Croat communities of Western Herzegovina, adjacent to the Republic of Croatia, and those intermingled among the Bosnian Muslims in Central Bosnia.

The Bosnian Croats built up a military force outside of the Muslim-dominated Bosnian army. The Croatian Defence Council (HVO) was the smallest of the three main armies, never numbering more than about 50,000 men. Just as the Bosnian Serbs received clandestine support from Serbia throughout the war, so the Bosnian Croats received clandestine support from Croatia. When the HVO flagged, or needed to go on the offensive, Croatia provided formed military units. Despite this, and despite benefitting from Croatia’s access to the international arms market, the HVO was too small and dispersed to be an effective fighting force for most of the war. A revolving door of military commanders, including a theatre director, did not help.

Pulled in different directions by its Herzegovinian and Central Bosnian constituencies, and by Zagreb, the Croats struggled to find a consistent war strategy. In the first year of the war, the Croats fought with the Muslims against the Serbs; then with the Serbs against the Muslims in the following year; then were quiet for a year, before finally ending up where they had begun, allied once more with the Muslims against the Serbs.

When, in the final act of the war, Croat forces rolled back the Serbs, this was mainly Zagreb’s Croatian Army, rather than the HVO.

How they fought

The war in Bosnia was not, for the most part, manoeuvre warfare, and it was not genocide. Except in its closing stages, the war most resembled a form of high-intensity gangsterism. At the very end, it began to tip into genocide, and manoeuvre warfare began in earnest.

From the beginning, all sides fought the way they did with an eye to their respective political goals. However, all three nationalist establishments were riven by factionalism, leading each to cling to maximalist, and sometimes incoherent, programmes in an effort to create the broadest possible base of support.

The Serbs had the upper hand in the opening phases of the war. They focussed first on ethnically cleansing the Muslim-majority areas adjacent to Serbia, and then on securing areas traditionally inhabited by Serbs and strategic linking territories. They also seized other exposed areas, intending to trade these back in a final settlement, under what they imagined would be a “land-for-peace” agreement. Their method was to terrorise the population by killing non-Serbs, expelling populations, burning homes and institutionalising sexual violence, including rape and sexual slavery.31

For areas they could not incorporate into Republika Srpska, they mainly relied on sieges as a way of putting pressure on their enemies to accept their terms. A legacy of the long Ottoman rule was that Muslims were more numerous in the towns which lay along Bosnia's many valleys, while Serbs were more numerous on the higher ground. Secure on this higher ground, Serb forces cut off food and other supplies to the valleys below, and bombarded them, often at random, and terrorising the local population with sniper fire.

After three years, when the Serbs came to believe that ethnic cleansing and sieges alone would not force a political deal, they tried an even more aggressive approach that included mass killings around the UN-designated “safe area” of Srebrenica. The International Court of Justice ruled that the war had not been a genocide, but that the killing of some 8,000 Muslim men and boys around Srebrenica had constituted a “genocidal act”.32

The Muslim mode of warfare was, for much of the war, quite different. As the largest community, they had the biggest base for military recruitment, but they began the war with few trained officers, little heavy weaponry, and without reliable access to the international arms market. The Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina was initially defeated almost everywhere. Their strategy, therefore, was to defend whatever they could, while doing their best to create the conditions for a Western military intervention on their behalf.

Hoping to prompt the West into action, the Muslims tried to make things appear even worse than they were. Death tolls, particularly of civilians, were hugely exaggerated (and readily believed and repeated by Western observers).33 Civilians were prevented from leaving urban areas under siege. Even if this did not make them human shields per se, it exposed them, in the presence of the Western media, to Serb sniper fire and shelling.34 Convoys evacuating Muslim civilians from Srebrenica and elsewhere were blocked by the Muslim authorities.35 When the Serbs did not cut off the water and electricity to Sarajevo, the Muslims did.36 Ceasefires were violated, prompting murderous Serb responses, and UNPROFOR units were attacked by Muslim forces, who then blamed the Serbs.37

The Western media, and the new 24-hour news cycle played a key role in this strategy. Based mainly in Sarajevo, the media shared some of the dangers and hardships of the besieged population, and were sympathetic. Images such as the blood of children spattered against the snow; elderly killed while queuing for bread or water; snipers hunting men and women of all ages; civilians clambering from buildings burning under shellfire; and ancient libraries burning, dominated Western media coverage. This prompted calls for something to be done for the victims, and contributed to the erratic, on-again-off-again nature of Western policy making.38

While the Western media coverage was real, it was not the whole story. Violence was certainly directed at the general population rather than just at enemy forces, but the proportion of civilian casualties was relatively low by the standards of modern warfare. Of the approximately 110,000 war deaths, some 70,000 were military, and about 39,000 were civilians. Civilian deaths thus accounted for about a third, and for somewhat under 1% of the total population.39 Likewise the violence was not as one-sided as it appeared in the media. Muslims accounted for just under two-thirds of the total war deaths, while Serbs and Croats accounted for one third.40

As the war and the sieges dragged on, with the Western world sympathetic but unwilling to intervene militarily, the Muslims invested more of their energy on other approaches. They formed an awkward triangle with Iran and the US to circumvent the UN arms embargo that the US had voted to put in place, and welcomed foreign mujahidin fighters, including “Afghan Arabs”, and others who would soon become part of Al Qaeda. They also ramped up efforts to train and organise a proper army whose superior numbers could be brought to bear.41

Deployment of UNPROFOR and the Vance-Owen Peace Plan

With the collapse of the Carrington-Cutileiro plan, and Bosnia's descent into full-scale war, the UN launched a major humanitarian effort. This became the world's largest humanitarian operation, and included an airlift into the besieged city of Sarajevo, the largest since the Berlin airlift of 1948-1949.42

To protect its humanitarian operation against the mayhem on the ground, the UN Security Council extended its peacekeeping operation from Croatia to Bosnia. In August 1992, Security Council resolution 770 gave UNPROFOR the mandate to take “all measures necessary” to facilitate the delivery of humanitarian assistance to Sarajevo and elsewhere. One month later, resolution 776 authorised an expansion of the force to allow it to support aid convoys across much of the country. The force grew in fits and starts, eventually numbering 39,000, or a little less than one tenth the size of three main warring armies.43

The UN humanitarian effort was an overwhelming success. Bosnia was one of the few major wars in which almost no-one died of either hunger or cold. Neither the humanitarian operation nor its protection force, however, was a mechanism to end the ethnic cleansing or the sieges. Nor was the Security Council’s imposition of a “no-fly zone” more than a minor impediment to the Serb campaign.44 As the war intensified, therefore, a new peace initiative was launched, with former US Secretary of State Cyrus Vance representing the UN and former UK Foreign Secretary Lord David Owen representing the European Union.

Vance and Owen developed a plan that followed the same consociational logic as the Carrington-Cutileiro plan, and the same matrioshka format of involving Serbia and Croatia in the talks, as well as their Bosnian Serb and Bosnian Croat counterparts. The central proposal was the territorial arrangement under which the country would be divided into ten cantons, each dominated by one or other of the three groups, but each with a power-sharing administration to reflect the pre-war mix of populations. The Serbs, who were still holding some 70% of Bosnia's territory, were to be allocated control of cantons comprising just 43% of the territory. Moreover, so as not to reward Serb ethnic cleansing, and to foreclose the possibility of the country being partitioned, the Serbs were divided into five isolated blocks of territory, the largest of which was the one furthest from Serbia.

The plan was presented in early 1993 and immediately attacked from all quarters. It was opposed by the Bosnian Serbs who were in a position of strength and felt they could do better; and it was opposed by liberal Western opinion, particularly in the US where Vance and Owen were accused of “moral appeasement” and of “carving up” Bosnia and denounced for negotiating with Milošević and Karadžić.45

Revised Vance-Owen Peace Plan, February 1993

President Clinton had declared himself in favour of a policy of “lift and strike” – lifting the UN arms embargo established before the war broke out in Bosnia, and using air strikes against Serb targets. With the Vance-Owen plan floundering, Secretary of State Warren Christopher was dispatched to Europe to promote the strategy among European allies. Meanwhile, however, unbeknownst to most, President Clinton had decided against trying to implement such a policy.46

Washington's solution to this conundrum – of publicly supporting a much more robust military option, but privately opposing that option – was to publicly support the Vance-Owen plan, while making it clear that the US would do nothing to help implement it on the ground. Clinton's National Security Advisor, Anthony Lake, briefed European ambassadors in February 1993 that the US was now “strongly supporting” the Vance-Owen plan, but “had sought to disabuse the Bosnian Moslems of any notion that there would be any US military intervention on their behalf.”47 The Bosnian Serbs correctly read this as an unwillingness to impose a settlement on them, and rejected the deal.48

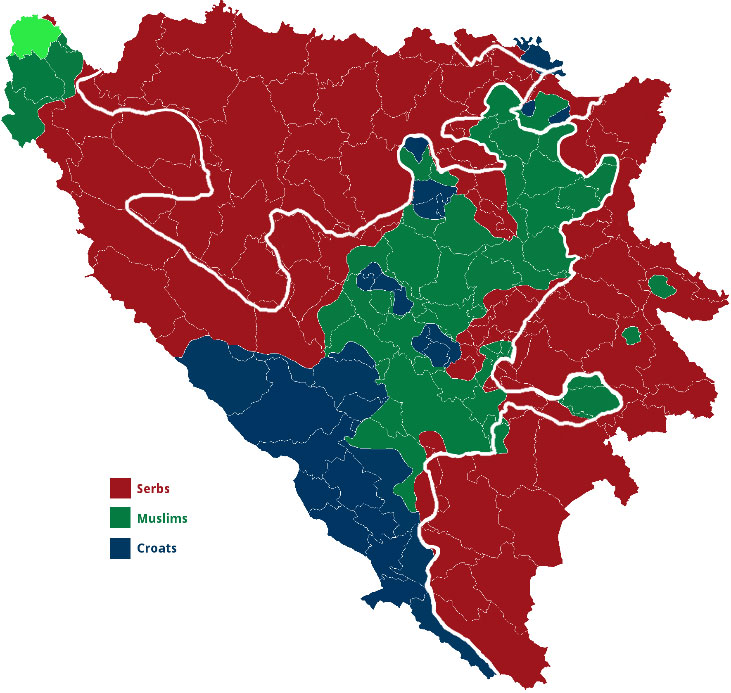

Approximate Territorial Holdings 1993-1995, and Dayton Inter-Entity Boundary Line, November 1993

The Joint Action Plan papers over differences among the main international actors

The United States did not respond to the rejection of the Vance-Owen Peace Plan with “lift and strike”. Rather, it decided to work with its partners – France, Russia, Spain and the United Kingdom – to find “new ideas”, and to “manage” the situation on the ground through the enhanced use of the UN peacekeeping force, to which it would not contribute forces of its own.

The “Joint Action Plan” was a diplomatic compromise that might have made sense to those who made it, but only made the situation worse on the ground. Its core idea was the establishment of “safe areas” for six Muslim-held areas under siege by the Serbs – Bihać, Goražde, Tuzla, Sarajevo, Srebrenica and Žepa. UNPROFOR was to be mandated to protect these areas. The UN Secretariat objected vigorously, arguing that UNPROFOR was neither equipped nor configured for this: it was a peacekeeping force comprised of lightly armed, dispersed, and highly visible forces in uncamouflaged white vehicles. It was deployed for escorting aid convoys, operating Sarajevo airport and monitoring front lines; not for force-on-force warfare.49

Nevertheless, the safe areas were created by the Security Council on 6 May 1993. The US then co-sponsored Security Council 836 extending the mandate of UNPROFOR to “deter attacks” on the six safe areas, and calling for more troops. Secretary General Boutros-Ghali insisted that 34,000 additional troops would be required for the new mission, stoking a conflict with the US from which he never recovered. An additional 7,000 troops were ultimately provided, mainly by France, leaving the safe areas exposed. The new approach was later described by Owen as “an ill-conceived and dangerous policy [which] ... paved the way for the predicted disaster at Srebrenica.”50

In addition to exposing the people who lived in the six enclaves to mortal danger and undermining UNPROFOR, the new policy also created confusion in the UN-NATO relationship. Resolution 836 mandated NATO to use air power to support UNPROFOR in the performance of its new mandate. This was to happen “under the authority of the Security Council and subject to close coordination with the Secretary-General and the Force.”51 A complicated “dual key” arrangement was established, requiring both the UN and NATO to agree to the use of air power on any given occasion, with one set of arrangements for “close air support”, and another for “air strikes”.52

As well as establishing safe areas, the US also led the Security Council in establishing an International Tribunal “for the sole purpose of prosecuting persons responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in the territory of the former Yugoslavia.” The founding resolution optimistically asserted that “the prosecution of persons responsible for the above-mentioned violations of international humanitarian law will contribute to ensuring that such violations are halted …”53 This illusion was immediately disproved on the ground.

The Croats and Serbs, seemingly oblivious to these initiatives, reacted to the collapse of the Vance-Owen Peace Plan by going on the offensive. The Croats went to war with their erstwhile Muslim allies, attempting to carve out their Croat Republic of Herzeg-Bosna by force, just as the Serbs had already done with Republika Srpska. Beginning with a massacre of Muslim civilians in Central Bosnia, this campaign included familiar elements of ethnic cleansing, bombardment of civilians, and the destruction of cultural heritage, including the iconic Old Bridge at Mostar. The Croat campaign, however, was a military failure, and by the end of 1993 the Croats had been defeated in much of central Bosnia.54 They were then pressured by Zagreb and Washington to enter into a Federation with the Bosniacs, re-creating a joint front against the Serbs.55

The Serbs, seeing that there was still no Western appetite for intervention against them, also pushed forward, assuming that their enemies would eventually sue for peace. By April 1993, the Serbs were on the brink of taking the surrounded towns of Srebrenica and Žepa in Eastern Bosnia. Then, in a brief moment of success for the international community, they hesitated. Rather than taking Srebrenica, the Serbs agreed to a ceasefire in return for Muslim disarmament.56 In the summer, under the threat of NATO strikes, they hesitated again. Having taken Mt Igman, overlooking Sarajevo, the Serbs agreed to hand the area over to UN control – a decision that weighed against them as the war came to a climax.

The Owen-Stoltenberg Plan lays the groundwork for partition

By allocating each community territories in which they had constituted a pre-war majority, the Vance-Owen Peace Plan had envisaged a Bosnia in which ethnic cleansing was largely reversed. Moreover, with the communities divided into a patchwork of unconnected territories, secession would have been impossible. But with the US unwilling to commit to the implementation of an arrangement that might bring them into conflict with the Serbs, and with the Serbs more dominant on the battlefield than ever, the mediators attempted to structure the deal differently.57

Owen, now joined by former Norwegian foreign minister Thorvald Stoltenberg, proposed a "Union of Three Republics". Instead of dividing the Serbs up into the dispersed areas in which they had lived prior to the war, the new maps started from the reality on the battlefield. The Serbs would be allocated a single large block of territory, including the whole of the border with Serbia; the Croats would be allocated two smaller territories, both adjacent to the Republic of Croatia; and the Muslims would be provided with road links to connect the main body of their territory with isolated Muslim cities in Eastern Bosnia. A large Sarajevo district at the centre of the country would serve as a common capital.

The logic behind the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan was the opposite of that of the Vance-Owen Peace Plan. Rather than proposing an arrangement for an indivisible country and reversing ethnic cleansing, the emphasis would be on creating a deal that would be easier to implement on the ground.

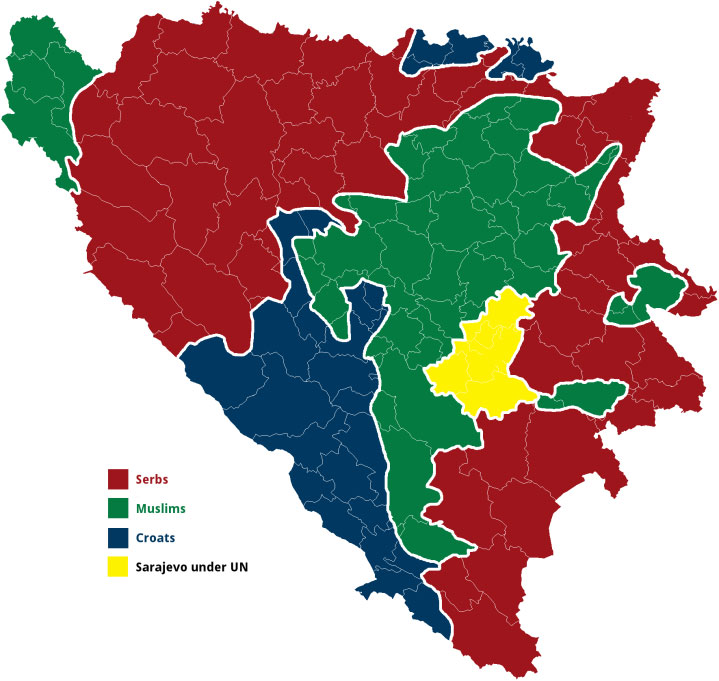

Owen–Stoltenberg proposal, August 1993

By allocating the Croats and Serbs territories that could easily be detached from Bosnia, the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan accepted that the three communities were not going to live together again. The partition that was a reality on the ground would be confirmed by agreement. This was affirmed by the parties, including in a Muslim-Serb declaration providing for referenda to be held after two years on whether or not the constituent republics would remain part of the Union.58

But there was a dilemma built into this for the Croats and Serbs. Under the terms of the proposed deal, the Serbs would have to give up almost a quarter of the land they held. Moreover, if either the Croats or Serbs were to leave the Union, they would lose their stake in the mixed Sarajevo district, the jewel in Bosnia's crown. Regardless, a provisional agreement was reached on board the British warship HMS Invincible on 20 September 1993. The Muslims would hold just over 33% of the land, including access to the River Sava in the North and the Adriatic Sea in the South; the Croats would hold almost 18%, and the Serbs 49%. Presidents Milošević and Tudjman as well as the representatives of the Bosnian Serbs and Bosnian Croats agreed with the proposal, and President Izetbegović informed the mediators that he would seek a “yes” vote. Just two days later, however, Izetbegović told the media that he was “personally not inclined” to accept the package, which was then rejected by the Muslim Assembly and the war continued.59

NATO threatens air strikes and UNPROFOR establishes ceasefires

The protagonists reacted in different ways to the collapse of this third attempt to reach a deal. Most visible, but least effective, were the Serbs who continued to believe that, if they controlled enough territory and inflicted enough pain, their enemies would seek peace on land-for-peace terms. They began in 1994 by tightening the siege of Sarajevo, which backfired in February when 70 civilians were killed in a mortar attack on Sarajevo’s main marketplace. A moment of unity between the UN and NATO produced a threat to bomb the Serbs if they did not pull back.

UNPROFOR’s Bosnia commander, Lieutenant-General Michael Rose, saw an opportunity to put a ceasefire in place around Sarajevo. This was resisted by the Bosniacs and their international supporters who hoped that, with NATO air support, they might be able to push the Serbs back. But Rose was adamant that the international community could either do peacekeeping or war-fighting, but not both at the same time. UNPROFOR, he insisted, was not a war-fighting force, and should not cross the “Mogadishu line” – the line he drew between peacekeeping and war-fighting, which the US had crossed in Somalia several months earlier, with disastrous results.60

Rose was supported by own civilian boss, Yasushi Akashi, fresh from a successful UN mission in Cambodia, and by Secretary-General Boutros-Ghali. Britain and France, as the main contributors of troops on the ground, were also in support. Arms were twisted, both in Sarajevo and in NATO capitals, and a ceasefire was agreed upon for the Sarajevo area. NATO established a “Total Exclusion Zone” for the heavy weapons of both sides.61

At one level, the Sarajevo ceasefire was a success. The bombardment largely stopped, casualty rates fell dramatically, and the flow of aid surged. The first glimmers of normal life began to return to Sarajevo, with the trams beginning to run again along Sarajevo’s notorious “Sniper Alley”. However, the logic of a Sarajevo ceasefire soon became apparent. Under threat of NATO air attack, the Serbs withdrew many of their heavy weapons from the heights above Sarajevo. But, confident that the Sarajevo front was calm, they opened a new offensive against the besieged Muslim enclave of Goražde, to the east of Sarajevo. They advanced, moving close to the city centre, and Rose called down limited NATO air attacks. The Serbs halted, negotiated a ceasefire, and then broke off their attack.

They tried one more time, in the western enclave of Bihać. A Bosniac-Bosniac war-within-a-war was being fought in that region between forces loyal to Izetbegović and those loyal to his erstwhile electoral partner, Abdić, the chicken tycoon. The Serbs intervened on behalf of Abdić, rolling back a pro-Izetbegović force that had briefly broken out, and then closing in on the city of Bihać itself. For the third time, the same sequence played itself out: the Serbs advanced; UNPROFOR called in limited NATO air attacks; the Serbs stopped; and a ceasefire was agreed.

The Serbs were at an impasse. Limited ceasefires suited them because they were over-stretched. But if every offensive was met by a new ceasefire, they could never take the cities they had besieged and could never bring the war to a conclusion. But if they refused to accept the ceasefires on offer, NATO, they feared, might intervene against them more forcefully.

A misleading calm established itself over much of the country. The Serbs and the international community were in a sort of stalemate. The Croats, chastened by their failed confrontation with the Bosniacs the year before, and pressured by Zagreb, accepted the peace agreement imposed by Washington. They used the hiatus to build their strength, and to work with the government of Croatia to prepare a new offensive, this time against the Serbs. As the year drew to a close, Croat units slowly began to advance westward, nudging the Serbs back from the border with the Republic of Croatia, leaving the Croatian Serbs almost surrounded in their would-be capital of Knin.

The Bosniacs, now despairing of the Western military intervention they had hoped for, began in earnest to build a credible fighting force. With support from the US and the Muslim world, the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina was quietly transformed into Bosnia’s largest fighting force. With some quarter of a million men in the field, and with the Croats having switched to their side again, the Bosniacs were at last ready to exploit the Serb over-stretch.

The Contact Group Plan

While all this was happening on the ground, the main Western powers formed a five-country “Contact Group” with Russia, in the hope of establishing a common mediation position. Russia was weak, having emerged much diminished from the break-up of the Soviet Union, but was seen by the West as an essential influence over the Serbs. Once formed, the Contact Group developed a peace plan of its own, including a plan to link acceptance by the parties to the new smart sanctions regime. This new deal was presented to the parties in August 1994.

The consociational model of the Carrington-Cutileiro, Vance-Owen and Owen-Stoltenberg plans was retained in the new Contact Group plan. What was new was the proposed division of the country not into three ethno-religious zones, but into two: the Bosniac-Croat Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Republika Srpska. This was an American formula, and came at cost. The designation of the areas under Serb control as a thing apart from the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina was attractive to the Serbs, whose goal was separation from the Bosniacs and Croats. Moreover, the constitutional and territorial arrangements of the Federation were convoluted, to accommodate difficult relations between Bosniacs and Croats.

The Owen-Stoltenberg formula of 49% of the land for the Serbs was continued under the deal proposed by the Contact group. With the Bosniacs and Croats now nominally a single entity, they were allocated the remaining 51% of the territory. Within these overall percentages, the Contact Group plan attempted to further “simplify” the map, smoothing out the boundaries in ways that were assumed to be easier to implement.

Contact Group Plan, July 1994

But the logic undergirding the Contact Group plan and the UNPROFOR ceasefire was flawed. With the guns largely silent, and the Serbs still holding 70% of the country, the Serbs felt little pressure to make major concessions. It was not calm on the ground that was needed to create the conditions for a political deal, it was military balance. Despite support for the plan from Milošević’s government in Belgrade, therefore, the Bosnian Serbs rejected the deal, recalling that they had supported the previous proposal, to which they still claimed to be committed.

UN sanctions against the Bosnian Serbs were then tightened, while those against Serbia proper were eased, on the condition that Serbia would apply sanctions of its own on the Bosnian Serbs. The monitoring arrangements for this sanctions regime were imperfect, and Belgrade avoided implementing the sanctions on the Bosnian Serbs where it could, but the noose was beginning to tighten on Pale.62

Although the Contact Group plan had largely failed, it had succeeded in partially isolating the Bosnian Serbs. Existing rifts between Belgrade and Pale were exacerbated by the new sanctions. Milošević was treated, if not as a partner of the West, then at least as a man with whom the international community could do business while Karadžić and the other Pale leaders were increasingly shunned as extremists. General Ratko Mladić and the Bosnian Serb military were caught in the middle – as extreme as the Pale civilian leadership, but largely loyal, or at least beholden, to Belgrade. These divisions grew over time and weakened the Serbs, a weakness that was a precondition for an eventual settlement.

The three sides prepare for a final confrontation

After the collapse of the Contact Group plan, several months passed with little further military action. And then the Serbs realised that everything had changed. The Serb leaders convened in the mountains above Sarajevo during the winter months of 1994-1995, concluding that the strategy which they had pursued throughout the war had failed. Time, rather than working in their favour, was against them. The Bosniacs and Croats were not going to make peace just because the Serbs held so much of the land, and Serbia was not going to support them to an overwhelming victory on the battlefield. Their enemies – the Government of Croatia, which outnumbered the Croatian Serbs by almost ten-to-one, and now also the Bosniacs – were growing in strength and would soon be able to defeat them.

The Serbs decided on a change of strategy. Rather than waiting for their enemies to grow stronger they planned to strike hard and force an end to the war in 1995. They would strangle UNPROFOR and the international aid mission that incidentally fed much the Bosnian army and allowed Sarajevo to resist the siege; they would eliminate the threat to their rear from the Bosniac enclaves in the East; and then they would pivot west, to prop up Abdić’s anti-Izetbegović forces in Bihać, and to prepare to confront the rising menace of Croatia.

Unrelated to this, the Bosniacs and Croats were also getting ready to go on the offensive. The ceasefire was cementing the Bosniac territorial disadvantages, and the return of some degree of normalcy was allowing Western attention to turn its attention elsewhere – undermining an essential part of the Bosniac strategy. Unwilling to settle just on the shreds of territory the early phases of the war had left them with, and with the population of Sarajevo unwilling to face another winter under siege, the Bosnian army was planning to break out of Sarajevo. Over the border in Croatia, Zagreb was almost ready for its final assault on the Croatian Serbs.

With all three sides now believing, for different reasons, that they needed to go on the offensive, the UNPROFOR ceasefire began to unravel. Former US President Jimmy Carter mediated a follow-on “Cessation of Hostilities Agreement” over the winter of 1994-1995, but this soon succumbed to the logic of a final military confrontation. Violations were limited at first, but then, as the snow thawed, greatly increased.

The Serb strategy to end the war in 1995 might have worked had they not miscalculated. The Serbs had grown accustomed to Western fecklessness, or, at least, to a certain gap between Western protestations of outrage and action. Assuming that there was no end to this, they pushed both the Bosniacs and UNPROFOR harder. They tightened the siege of Sarajevo, and resumed their bombardment of the city, ignoring the ceasefire. UNPROFOR’s new Bosnia commander, Lieutenant-General Rupert Smith (who had replaced Rose in January) ordered airstrikes against Serb forces. The Serbs retaliated, taking 400 UN soldiers hostage, which they only released against assurances from the international community that no more such strikes would be ordered. The apparent seal on this promise was the transfer of the UN “key” to turn on airstrikes from the UN mission on the ground to the UN Secretary-General in New York.63

UNPROFOR moves to war-fighting mode by stealth – how soon is now?

The hostage-taking was the turning point for the UN and UNPROFOR’s main backers. Smith began preparing for war with the Serbs, which needed to be done without their knowledge. He gathered together the nucleus of a small war-fighting force from the peacekeeping units on the ground and two combat-ready “Battle Groups” were formed – one British and one French. Above Smith, Britain and France were edging closer to the decision to commit their forces to war. France’s new president, Jacques Chirac, came to office wanting to take a stronger line against the Serbs, and UK Prime Minister John Major approved the deployment of an artillery regiment to reinforce the new Battle Groups. Some capacity and will to move against the Serbs was beginning to emerge, though it was still not decisive or thought-through.

In early June 1995, the British, French and Dutch decided to expand on Smith’s Battle Groups and announced their intention to form a Rapid Reaction Force to support UNPROFOR – or, if needed, to cover its withdrawal, possibly in the context of a shift to a “lift-and-strike” policy. The force was not to be in Blue Helmets and white vehicles, and was to be battle-ready. To allay Serb anxieties about this gathering force until it was ready to strike, Smith hid the command arrangements for the Rapid Reaction Force. He wanted all around him to believe that this was a NATO force, operating under NATO control, and nothing to do with the UN, except for administrative and logistic purposes. This, he believed, would give him the time he needed to move exposed UNPROFOR personnel to safety.64

At the beginning of July, the Serbs made their big move. On the 11th they overran the UN “safe area” of Srebrenica, sweeping aside a small force of Dutch UNPROFOR troops. Instead of just detaining the Bosniac military-age men and expelling the rest, as had happened in the past, they began to slaughter their victims. Within a week, some 8,000 Bosniac men and boys had been killed as they tried to escape the enclave, or had been captured and then transported to execution sites, and shot.65 The author of this paper visited a warehouse in which several hundred captives had been held. Gunfire and grenades had been directed through the windows from the outside, exploding the bodies of those within. Human remains – including blood and hair, some of it still attached to shreds of skin – were caked onto the walls, floor and ceiling.66

Enough, finally, was enough. The major international powers met in London just over a week later, and decided – or were considered by France, the UK and US to have decided, which was enough – that any further Serb outrage would be met with a military response. The authority to use air power was placed in the hands of the Force Commander – there was to be no further political component to the decision for its use. When it was unleashed, force would be used for as long as necessary. A British air-mobile brigade was deployed to Croatia to serve as a combat reserve for the coming operations.

There was still no real political strategy behind this, beyond a sense that the Serbs had crossed a line and that their atrocities could not go unanswered. Just as the tool of recognition had been de-linked from the deal-making process, thereby depriving the mediators of leverage, the same was now the case with the use of force.67

After the London meeting, Smith established a separate headquarters for the Rapid Reaction Force in the village of Kiseljak, outside of Sarajevo. By creating a separate headquarters, away from UNPROFOR’s main headquarters, Smith hoped to maintain the deception that the Rapid Reaction Force was not a UN instrument, and was not under his command. He also hoped to hide its real business, which was to work with NATO’s 5th Allied Tactical Air Force in the final planning for a military campaign against the Serbs.

General Smith met with NATO’s Commander-in-Chief Allied Forces South, Admiral Leighton “Snuffy” Smith, to put in place the last arrangements. The Smiths agreed that the NATO air operation was to be in support of the UN Ground Plan, when this was ready, and that both commanders would have to approve all targets. It was further agreed with the UN’s Smith would select all the targets, except for those to be hit as part of the suppression of Serb air defences.

Operation Deliberate Force

Events unfolded fast. The Republic of Croatia launched Operation Storm at the beginning of August, destroying the Croatian Serbs in a matter of days. Croatian forces then crossed into Bosnia in force, later advancing into the Serb heartland around the Western city of Banja Luka.

The UN had one last preparatory move to make before UNPROFOR joined in the fighting. The remaining Bosniac enclave in Eastern Bosnia, Goražde, contained a British battalion and a Ukrainian company. The UN’s Smith met with Mladić in early August, just after the Croatians had launched Operation Storm against the Croatian Serbs, and told him what he wanted to hear: that the Ukrainians would not be replaced when they left, and that the British battalion would probably not be replaced either. He claimed that the Bosniacs opposed this plan and might interfere, in which case Mladić should instruct his local commanders to give assistance to the withdrawing unit. Mladić, who welcomed the apparent abandonment of Goražde, agreed, and instructed his subordinates accordingly.

At the end of August, with the UN Rapid Reaction Force deployed and with the UN-NATO plans in place, the Serbs made a fatal mistake. On the 28 August, a mortar bomb killed several dozen people in Sarajevo’s main market place and, despite much noise to the contrary, there was never any real doubt in the minds of UN analysts that it was the Serbs who had fired this shell.68

Smith still needed a few more hours to get the last UNPROFOR troops to safety. Perhaps uncharitably, he decided that the UN’s most plausible cover story would be incompetence, so he feigned indecision and made bland statements to the Serbs and the media indicating that the UN was not sure what had happened at the marketplace and was looking into the matter. That night, the British battalion drove out of Goražde, through Serb territory, and out of the country to safety – in full view of the Serbs.69

The next morning, without direction from above but with the last UNPROFOR troops safe, Smith “turned the key” to launch the joint UNPROFOR-NATO military operation known as Operation Deliberate Force. Artillery bombardment and air strikes began that night. The plan was to break the siege of Sarajevo and thereafter to keep attacking so as to weaken the Serbs to a point that they would be willing to accept a political settlement on more-or-less reasonable terms. It was not much of a political plan, but for the first time, it was something.

The new UN artillery on Mt Igman opened fire from the land ceded by the Serbs to the UN in 1993. UNPROFOR bombarded Serb artillery and air defences around Sarajevo, preventing the Serbs from striking back at the UN or at Bosnian civilians and allowing NATO aircraft to engage Serb targets close to Sarajevo, as well as elsewhere across the country. Two days later, Smith informed the Serbs that he was opening a route out of Sarajevo over Mt. Igman. For over three years, the Serbs had controlled this road with their heavy guns. On 2 September, Bosnian civilian traffic, protected by UNRPROFOR artillery, surged, and grew with each passing day. The three-year siege of Sarajevo was broken.70

The end of the war

Over the coming weeks, the Serbs fell back before the advancing Croatian forces, were pressed by the Bosniacs along the line of confrontation, and were bombarded by UNPROFOR and NATO. By late September, they had lost much of the land they had taken since 1992 and were on the brink of collapse. By early October, the Serb stronghold of Banja Luka lay open to the Croatian Army.

Suddenly, desperate to end the war and hold what territory they could, the Serbs participated with new enthusiasm in the revived peace efforts now led by Richard Holbrooke of the US and former Swedish Prime Minister Carl Bildt. The Serbs needed a ceasefire to stop the haemorrhaging on the battlefield, and they needed to lock in the concessions that had been made to them when they were strong: 49% of the territory, and the weakest possible central government.

Holbrooke had joined the negotiating effort recently, and had been caught unaware by UNPROFOR’s decision to turn the key that launched the joint UNPROFOR-NATO offensive.71 A professional diplomat with experience on Wall Street, Holbrooke brought extraordinary drive and a deal-maker’s approach to the situation. His weakness, however, was egotism, which Milošević exploited. In pursuit of the ceasefire and the deal he needed, Milošević flattered Holbrooke saying that he could take credit for ending the siege of Sarajevo and that he alone could end the war.72 He also agreed with Holbrooke that he would lead the Serb delegation himself, sidelining Karadžić and the other Bosnian Serb leaders (whom Milošević also wanted sidelined).

Holbrooke privately encouraged the Bosniacs and Croats to take what territory they could straight away, but, with Milošević’s encouragement, publicly joined the international push for a ceasefire. The Bosniacs bridled, feeling that they at last had the military upper hand. But without US support, they had little choice. On 5 October, UNPROFOR presented the parties with a ceasefire proposal. The Bosniacs insisted on provisos with respect to the restoration of utilities in Sarajevo, but these bought them just five days for further campaigning.73

Serb forces withdrew from the western towns of Mrkonjić Grad and Sanski Most on the night of 9 October, leaving a small number of mainly elderly civilians to their fate. Croatian and Bosniac forces advanced, taking the towns with no further fighting, burning houses, and driving out the remaining civilians. The last shots of the war were fired on 10 October 1995 as the war ended as it had begun – with sporadic violence against civilians – and then the guns fell silent. UNPROFOR forces demarcated the final front lines, separated the forces, oversaw the withdrawal of heavy weapons, and established liaison offices and mechanisms for investigating and dealing with reported violations. By mid-October, violations of the ceasefire – mainly encroachment into areas between the front lines – had come to an end.

The Dayton Agreement: An Elite Bargain

Peace talks began on 1 November 1995, two months after the siege of Sarajevo had ended and three weeks after the last shots of the war had been fired. The agreement was negotiated over a three-week period at the Wright-Patterson Air Base in Dayton, Ohio, chosen by Holbrooke to isolate the parties and awe them with the spectacle of American power. Holbrooke took almost exclusive control: the UN was excluded other than for side talks on the Eastern Slavonia region of Croatia; and representatives of the Contact Group countries were present, but were mostly isolated from the talks themselves. No contact beyond the base was permitted.

The three delegations were led by the Presidents of Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia, the same three leaders who had led their communities to war in 1991 and 1992. Bosnian Croat and Bosnian Serb leaders were present, but under the authority of the Presidents of Croatia and Serbia. There was no representation for non-nationalists, the smaller communities, or women or civil society, nor was there provision for consultation, review or approval. Despite such narrow representation, Holbrooke decided to try to lock in agreement on all issues on which the leaders could find common ground: “What was not negotiated at Dayton,” he argued, “would not be negotiated later.”74

The General Framework Agreement for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina – the Dayton Agreement – comprised a brief chapeau and 11 annexes. Annexes 1 A, 1 B and 2 cover military matters, regional stabilisation and the establishment of the “Inter-Entity Boundary Line” separating the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina from Republika Srpska. The military annexes called for a deployment of a NATO-led Implementation Force (IFOR), but just for one year, as part of an internal US deal.

The rest of the agreement is divided into nine parts covering non-military aspects of the agreement:

Annex 3, on elections;

Annex 4, the full text of the new Bosnian constitution;

Annex 5, on the arbitration of disputes between the two entities;

Annex 6, on human rights;

Annex 7, on refugees and displaced persons;

Annex 8, on national monuments;

Annex 9, on public corporations;

Annex 10, on civilian implementation and the High Representative; and

Annex 11, on the international police taskforce.

To the extent that there would be oversight of these arrangements, it was agreed among the major international actors that an ad hoc group of countries should form a Peace Implementation Council (PIC) to appoint a High Representative. The PIC would report to the Security Council on its work, but would not receive guidance from it.

Key Features of the Elite Bargain

Four main features of the Dayton deal stand out. First, the Serbs got an exceptionally good deal. The 51:49 formula was taken from the Owen-Stoltenberg Plan, when the Serbs held over 70% of the country despite the fact that the Serbs were now much diminished. By the time they arrived at Dayton, they had lost all of the “extra” land they had held, and were on the brink of military disaster. US observers had objected to earlier plans that were seen as too generous to the Serbs, starting with the Lisbon Agreement in 1992 which allocated the Serbs 44% of the land. But the Serbs were now offered 49%, and gladly accepted.

Second, Dayton drew heavily on the earlier peace plans, but in perverse ways. The Vance-Owen plan would have blocked Serb secessionist ambitions by limiting Serb control to the isolated areas in which they had constituted a pre-war majority. This arrangement was dropped at Dayton in favour of the option the Serbs preferred, of a single territory, including on ethnically cleansed lands which had previously had non-Serb majorities. The Owen-Stoltenberg plan would not have blocked Serb secessionist ambitions, but proposed a constitutional arrangement that would have been much easier to implement. This was also dropped at Dayton in favour of more convoluted arrangements. The worst feature of the Contact Group plan was the awkward division of the country into two political entities rather than three, to the delight of the Serbs and the frustration of the Croats. This feature was retained at Dayton.

Third, and with far-reaching negative consequences, the Dayton annexes included a full constitution for the country. The original language of Bosnia's constitution is English, and much of the drafting was done by State Department officials. The constitution was designed to allow each community to block actions by the other communities. In practice, it created a decision-making mechanism that would be difficult to implement even with good will on all sides, and established a system of government so heavy that it would be unaffordable in a much wealthier country. Above all, the constitution locked in the ultra-nationalist preferences of three presidents. For example, it provided that one of the three members of the collective Presidency would be a Serb directly elected from Republika Srpska. It was excluded, under the constitution, that a non-Serb in Republika Srpska should even contest this seat, just as it was excluded that a Serb in the Federation should seek to become a member of the Presidency.75

Fourth, whatever its other strengths and weaknesses, the agreement was going to be hard to implement. The bulk of the agreement was focussed on the military arrangements and the mandate was strong, but the nine civilian annexes less detailed and the mandates often weak. Compared with the sweeping powers granted to the Commander IFOR, the modest role given to the civilian High Representative was striking. This was a US decision, rather than the result of a negotiated compromise by the parties, intended to ensure that the civilian High Representative would have no authority over IFOR – the authority of UN civilians over the UNPROFOR Force Commander being seen by the US as a negative lesson from the previous period. The effect was to hobble the implementation of the civilian provisions of the agreement.

Implementation of the Dayton agreement – the first year

The implementation of the Dayton agreement was not a success. IFOR was exceedingly cautious and did as little as possible to implement the military aspects of the agreement, while the civilian aspects got off to slow start and then stumbled.

On 22 December 1995, UNPROFOR handed over command to NATO: IFOR was effectively created by the majority of existing UN contingents simply switching their blue berets to their national colours, and painting their white vehicles green; and the US contingent, notably absent from UNPROFOR, crossed into Bosnia early in 1996. The deployment of IFOR posed no major challenges. The war had ended almost three months earlier, with the front lines long-since stabilised by UNPROFOR forces, with its peacekeeping force operating unhindered throughout the country.

Unlike UNPROFOR, IFOR had overwhelming military force at its disposal, an unrestricted mandate, full operational autonomy, and no war on the ground. Nevertheless, IFOR's priority, at the insistence of the US, was to ensure zero IFOR casualties. Despite a mandate to do so, therefore, IFOR refused to offer protection for civilians who wanted to remain in their homes, or to displaced people who wanted to return home.

The first impact was on refugees and on Bosnians of all communities who found themselves on the wrong side of the ethnic divide. With the end of the war, hundreds of thousands of refugees returned to Bosnia, or were returned to Bosnia by the countries which had sheltered them. With IFOR unwilling to use its protection mandate, however, many of those returning opted not to go back to their original homes, but rather to new homes in “their” areas – Bosniacs and Croats to the Federation, Serbs to Republika Srpska. As a result, the areas that comprised the Federation became overwhelmingly Bosniac and Croat, and the area that made up Republika Srpska became overwhelmingly Serb.

The consolidation of ethnic cleansing was particularly visible around Sarajevo, which had once been a thriving, multi-confessional home to all of Bosnia’s communities. By the end of the war, approximately 100,000 Serbs lived in parts of Sarajevo which were to be transferred to the Federation. Many of those fled before the transfer took place. Many of those who did not flee of their own will were burned out of their homes by Serb extremists who were opposed to Serbs living in the Bosniac- and Croat-dominated Federation. Many of the rest were then driven out by incoming Bosniac extremists. Although many of the most egregious attacks took place at the perimeter of its Ilidža headquarters, IFOR chose not to intervene.76

Just as serious as IFOR’s inaction on the military front were problems on the civilian side. If IFOR had huge capacity but little will to act, the opposite was true of the civilian implementation of the agreement. Carl Bildt, former Prime Minister of Sweden, was appointed by the Peace Implementation Council to be first High Representative. When appointed, Bildt had almost no staff, a small budget, and very limited authority, either over the parties or over the work of the different international organisations charged with the implementation of the various annexes.77

The arrangements on elections were particularly damaging. Dayton required that elections should take place within 6-9 months, under the supervision of the Organisation for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE). This time-frame was an error, but suited those at Dayton: the three nationalist leaders whose parties were in de facto control on the ground and who controlled the media and the economy; and the Americans who wanted to see benchmarks of success and a drawdown of IFOR before the US Presidential election of November 1996.78

In their haste, and to avoid a confrontation with the nationalist establishments, the OSCE agreed an election system that encouraged zero-sum competition between representatives of the three parties. There was no requirement for candidates of one community to receive any votes from the others. As a result, the only competition was among candidates to mobilise their own core constituencies. This was done by fear-mongering about the other communities, and any moderate voices that could have spoken across community lines were marginalised.