Unpacking Complexity in the Ukraine Peace Process

17 Apr 2019

By Anna Hess Sargsyan for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This article was originally published in the CSS Analyses in Security Series by the Center for Security Studies on 3 April 2019. The article is also available in German and French.

The armed conflict in and around Ukraine entered its fifth year with ongoing ceasefire violations and with no political resolution in sight. The multi-format peace process dealing with the conflict, known as the Minsk Process, has very modest outcomes to show for it, despite regular meetings within the Trilateral Contact Group format, the mechanism mandated to work out modalities of implementation of the Minsk agreements. In the run-up to presidential and parliamentary elections in Ukraine, the implementation of the security and political provisions of the Minsk agreements, signed under international pressure, remain elusive.

When a peace process lasts for four years without tangible outcomes, it becomes an easy target for criticism as being ineffective and irrelevant, and runs the risk of discrediting conflict resolution efforts. Some scholars pondered whether the conflict in Ukraine would become yet another protracted conflict that Russia would use to secure its stronghold in the post-Soviet space. What seemed to be only a speculation back then, has turned into bitter reality.

This growing critique of the Minsk Process needs to be assessed by unpacking its complexity. A close look at the conflict background, the issues of contention and the key elements of the existing peace process allows for a better understanding of the political and technical realities around it. An analysis of the rationale and positions of the parties sheds light on the influence of these factors on the process dynamics and outcomes. This context and process analysis in its turn raises the underlying question as to how effective the implementation of agreements can be if they were signed under pressure and how any process can move ahead if the parties involved lack the political will to do so. Unpacking this complexity not only sheds light on the challenges of the Minsk Process, but also helps identify openings for potentially revitalizing a deadlocked peace process.

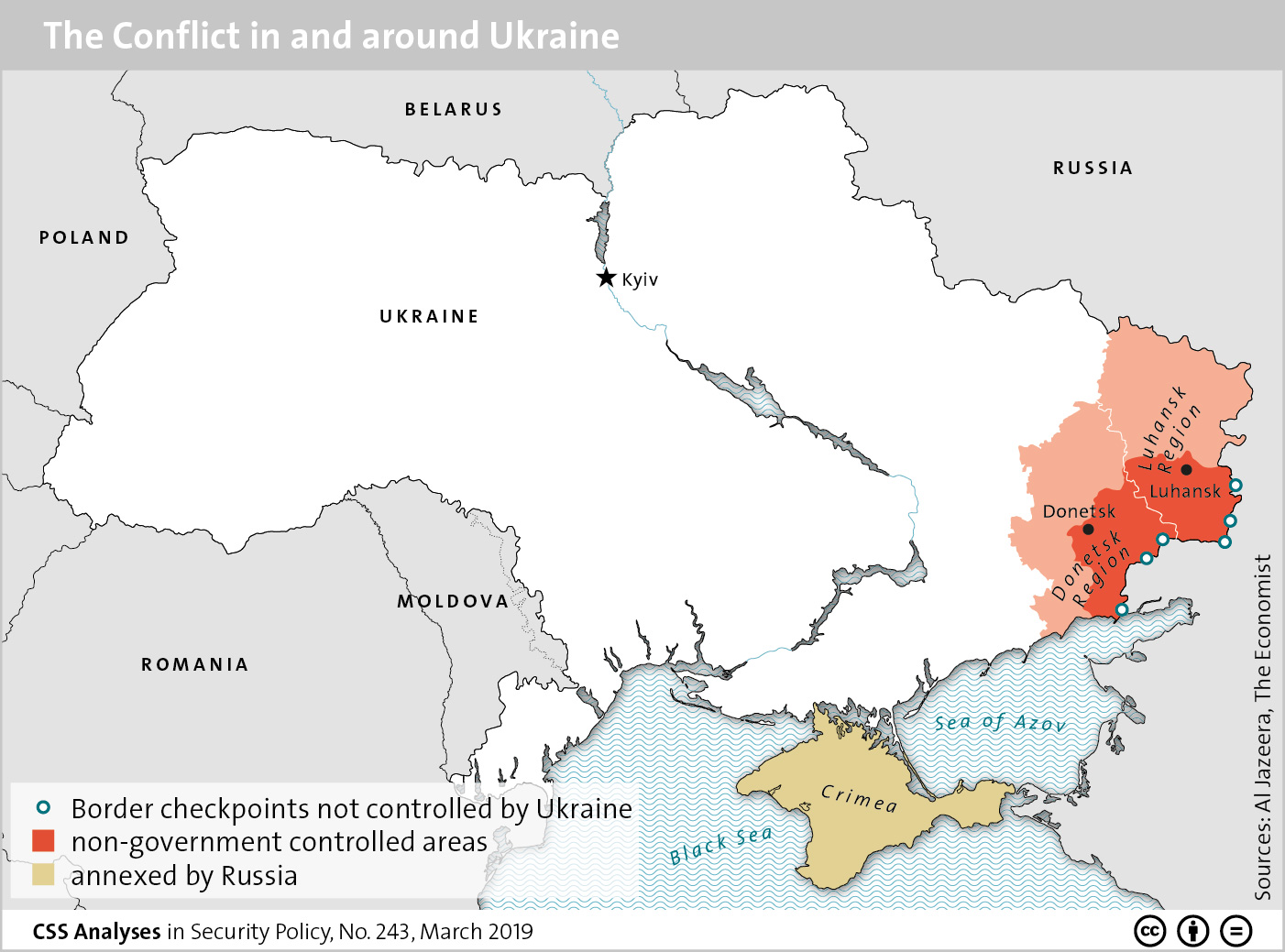

The conflict in and around Ukraine

In November 2013, then Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych backed out of the signature of the Association Agreement with the European Union. Full of disappointment, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians went out into the streets of Kyiv. The rapidly unfolding instability spread to the rest of the country and caused Yanukovych’s ousting. The power vacuum in Kyiv was followed by the annexation of Crimea by Russia and unrest in eastern Ukraine, ultimately leading to the breakaway of some parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Full-blown hostilities broke out between Russia-backed separatist forces in the two regions and the fledgling Ukrainian army, which left Donbas divided with a contact line between government controlled areas (GCAs) and non-government controlled areas (NGCAs). The loss of Crimea, the NGCAs and the control over its border with Russia undermined Ukraine’s sovereignty and further destabilized the country.

Over the past five years, the highly escalated conflict has turned into a low simmering conflict, with regular ceasefire violations and alarming human, economic and political costs. It has claimed around 13,000 lives on all sides and caused massive displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. It has left a whole region with a devastated economy and aging population in dire humanitarian conditions. All these factors led to the erosion of trust on many levels, causing an ongoing political and security standoff between Ukraine and Russia, a political and economic standoff between Russia and the West, antagonism and deteriorated relationships between societies in Ukraine and Russia, and severed ties between Ukraine and its NGCAs. Despite all the low points in the relationships of key actors of the conflict, however, they all remain committed to the settlement of the conflict in and around Ukraine through the Minsk Process.

To understand the conflict resolution initiatives and the content of the Minsk agreements at their basis, there is a need to outline the issues of contention and to understand the competing narratives on the causes and the consequences of the conflict in eastern Ukraine. Having lost Crimea to Russia and NGCAs to Russia-backed separatist entities, both the Ukrainian government and civil society alike see Ukraine as bearing the brunt of the conflict. Feeling attacked by its neighbor and one-time ally, Ukraine sees the conflict as orchestrated from outside and a blatant meddling in its internal affairs.

Russia on the other hand sees the conflict as being between Kyiv and the breakaway areas, justifying its annexation of Crimea as a means of protecting Russian-speaking populations abroad, while providing support to the separatist entities without openly acknowledging it. Russia saw the Maidan protests as a regime change orchestrated by the West and hence a direct threat to its geopolitical interests. Losing Ukraine to the EU is a major blow to the Eurasian Economic Union, Russia’s grand economic scheme in the post-Soviet space.

The West, in particular the US, Germany and France perceived the Maidan protests as homegrown and genuine demonstrations against a corrupt and oligarchic regime, in their own right. There is a widespread perception that Ukraine’s strive to become part of the European family of countries and to pursue its independent security and foreign policy got hijacked by the conflict instigated by Russia.

When it comes to the breakaway areas of Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine, little space is given to their narratives. Unrecognized by anyone internationally, including Russia, who is their political and military guarantor, these de facto authorities are seen as marionettes from all sides – the West, Kyiv and Moscow alike.

These diametrically differing perspectives on the conflict are reflected on the parties’ positions on issues at the heart of the conflict and their perceptions of who the direct conflict parties are. The most salient question for Ukraine is full restoration of its territorial integrity accompanied by a demilitarization of the NGCAs from foreign troops, whereas for Russia the political resolution of the conflict and the status of the self-proclaimed breakaway entities are central. This presents a considerable challenge for any third party and matters for key aspects of peace process design, in particular for the format and the agenda of talks, the participation of all relevant actors, their mandates and decision making power, as well as their commitment to potential agreements. The multi-layered Ukraine peace process is a reflection of these complexities and provides the parties with diverse formats for negotiation mechanisms to tackle issues of contention on multiple levels.

The Minsk Matrix: Multiple Formats

An amalgam of third party efforts ranging from diplomacy, high-powered mediation to technical talks were underway to settle the conflict already in its early stages in 2014. As the conflict was still flaring up, the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) under the Swiss presidency managed to set up a Special Monitoring Mission (SMM) with an agility and speed unprecedented for the organization. Deployed in March 2014, after the annexation of Crimea and before the breakout of violence in the East, the SMM has been continuously facilitating local ceasefires. It has a mandate to “ensure effective monitoring and reporting of the situation on the ground, and towards reducing tensions and fostering peace, stability and security in Ukraine.”

On 6 June 2014, on the fringes of the Normandy commemoration, German Chancellor Angela Merkel together with then French president François Hollande brokered the first meeting between Russian President Vladimir Putin and the newly elected Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. The concerted diplomatic effort resulted in the creation of Normandy format (N4) on the level of heads of states and governments, and/or foreign ministers. On the same day, the N4 decided to set up the Trilateral Contact Group (TCG), to be comprised of one representative from Ukraine and Russia respectively, with a Special Representative to be designated by the OSCE Chairperson-in-Office as its third member.

Despite the high-level diplomatic initiatives, military logic on the ground prevailed. The Ukrainian army was losing ground to the Russia-backed forces in the East incurring major territorial losses. The Minsk agreements – the Minsk Protocol and Memorandum of September 2014 and the Package of Measures for the Implementation of the Minsk Agreements of February 2015 – followed major military losses for the Ukrainian army. They were both negotiated within the N4 format and serve as the basis of talks today within the Minsk Process. The circumstances under which the Minsk agreements were signed, the public perception that Ukraine is forced to make too many unilateral concessions and the fact that Russia is not mentioned as a conflict party, combined with the exclusion of the Crimea question have led to the reluctance of both the Ukrainian society and the political elite to support the Minsk Process.

The Minsk agreements entail key political, security, economic and humanitarian provisions. They call on all conflict parties in eastern Ukraine to observe immediate full-scale ceasefire, guarantee the withdrawal of heavy weapons, and for the Ukrainian constitution to allow for decentralization of power. The Minsk agreements further stipulate the release and exchange of hostages, restoration of socioeconomic ties between NGCAs and the rest of Ukraine, amnesty for persons directly involved in the events leading up to the breakup of the NGCAs, and full restoration of Ukraine’s sovereignty, including the control of its border with Russia. To come up with concrete implementation measures on the four key clusters, the Minsk Package of Measures also stipulated for the creation of four Sub- Working Groups (WGs) under the TCG.

In essence, the N4 acts as a political guarantor of the Minsk Process, namely the TCG, which in turn offers a platform to the four WGs, mandated to tackle security, political, humanitarian and economic issues respectively. While the Normandy format tackles high-level political issues, the TCG is a trilateral convening body bringing together the two lead negotiators from Russia and Ukraine accompanied by the OSCE Special Representative and overseeing the work of the WGs. The WG discussion rounds are the only format where representatives of Kyiv and the NGCAs communicate with each other directly.

This unique setup lacks an institutional coordination mechanism among all the different formats, which can cause procedural challenges and hinder efficient linkages. However, the fluidity and multi-faceted nature of the Minsk Process allows for progress in one format even when work in the others is not moving ahead. While the political contexts in Ukraine, Russia and the West have not been conducive to enabling N4 meetings since 2016, the TCG and WG meetings have taken place almost every two weeks in Minsk and the SMM work on the ground has continued uninterrupted. To analyze the efficiency of the Minsk Process, it is hence important to understand the bigger picture with all the formats but disaggregate it when looking at the results. Eventually, this differentiated viewpoint helps us understand whether results serve the ultimate resolution of the conflict, dealing with its causes, or its management, dealing with its consequences.

Conflict Resolution and Management

A friend and foe for any third party, constructive ambiguity allows room for maneuver to bring conflict parties together for talks in the short run, like setting up the Minsk Process formats, but it might become a liability in the long-run. The fuzzy formulations of the Minsk agreements seem to generate space for multiple interpretations by the parties, hence making the chances for an agreement to implement specific measures very thin. This is further complicated by procedural questions. Proceedings are usually not recorded, which has direct implications for the roles and responsibilities of the parties present at the discussions. Furthermore, the parties’ lack of decision-making power at the table renders commitments very weak.

The current deadlock in the political and security working groups in the Minsk Process is by and large due to timing and sequencing of the key political and security related issues in the Minsk agreements. Moscow blames Kyiv for the lack of progress on the political provisions to allow for decentralization and local elections in the NGCAs, while Kyiv insists on full demilitarization of the conflict zone and restoration of control over the state border before implementing the political provisions fully.

However, incremental steps remain in place, such as the law on special status for certain areas of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions of Ukraine with a proviso that elections can take place in the NGCAs only in case of full demilitarization. On the security front, there has been marginal progress and withdrawal of weapons further away from the contact line. Seasonal ceasefires have contributed to a significant decrease of casualties in 2018. There have also been recent efforts to break the current political deadlock by introducing elements of a possible UN peacekeeping mission in the conflict zone, without much success so far.

While the sequencing of implementation of the political and security issues hinders substantial progress towards the resolution of the conflict, work has been progressing due to the dynamics within the humanitarian and economic working groups. Tangible efforts have been underway to alleviate livelihoods of the affected populations across the line of contact. Parties have been able to agree on a detainee exchange in 2017, to undertake joint efforts for water provision from GCAs to NGCAs and guarantee respective payments. Repairs of water infrastructure along the line of contact take place due to the regular discussions in the Minsk meetings. Also, the parties have managed to agree on the restoration of the Vodafone network in the NGCAs, the only mobile phone service across the line of contact.

Switzerland and the Peace Process

In June 2014, during its OSCE Presidency, Switzerland appointed Swiss diplomat Heidi Tagliavini as the OSCE Special Representative for Ukraine. She served in this capacity within the Trilateral Contact Group from the summer of 2014 until June 2015. Since then, Switzerland has supported the Trilateral Contact Group and its four working groups through Ambassador Toni Frisch, OSCE Co-ordinator of the Working Group on Humanitarian Affairs. Furthermore, Switzerland deployed up to 16 monitors to and, until October 2018, Alexander Hug as deputy head of the OSCE’s Special Monitoring Mission in Ukraine

Matter of Political Will or Formats?

The brief summary of the challenges and successes of the Minsk Process highlights the nature of its work as that of conflict management, rather than conflict resolution. By serving as a regular communication platform, it allows for progress on humanitarian issues from saving civilian lives to enabling communication and access to basic services for a dignified life. However, the political settlement of the conflict remains elusive, ceasefire violations by armed actors occur regularly and socio-economic ties between Ukraine and its NGCAs remain severed.

The lack of tangible progress in the Minsk Process can be attributed to a constellation of factors, most conspicuously, to the lack of political will from key actors. The circumstances under which the Minsk agreements were signed illustrate the limitations of the use of pressure to bring parties to an agreement. With the Ukrainian army quickly losing ground to the Russia-backed forces in the East, the agreements were necessary to stop the violence on the ground and force the parties to talks. However, the agreement signed in a military logic of the unfolding events comes with its limitations and poses challenges for implementation. Ukraine had very little choice but to sign an agreement largely deemed by its public, the government and the parliament as being unfavorable. From the Russian perspective, the Minsk agreements need to be implemented both by Ukraine and the unrecognized breakaway entities. Neither political elites nor the domestic constituencies in Russia are in a position to oppose the Minsk agreements, and even though implementation of these provisions are closely linked to a lifting of the Western sanctions against Russia, this does not give them enough incentives to settle the conflict.

Given lack of political will from all parties combined with procedural and technical challenges, conflict parties can easily drag their feet and delay implementation, making the premise of a success for the overall Minsk Process rather shaky. Over time, a lack of tangible progress has further eroded trust between parties, positions have hardened, and societal perceptions of the utility and relevance of the Minsk Process have become even more unfavorable than they were before.

Whether it is possible to ripen parties’ political will and reinvigorate efforts to unblock the political impasse remains an open question. In the current year of both presidential and parliamentary elections in Ukraine, it is hard to imagine any progress. The larger political climate among Western actors and Russia is not conducive either for bringing in renewed energy into the political echelons of the Minsk Process. While so far all parties easily dismiss the Minsk Process as ineffective, they seem to tacitly agree that there is no alternative at present. With all its challenges, the Minsk Process has served as a communications and conflict management platform, with very modest but tangible results on the ground that improve the lives of those most affected by the conflict. It is in this sense that it should continue its work, because every life matters and as the classics say “jaw jaw is better, than war, war.”

Recent Issues in the CSS Analyses in Security Policy Series

- Lessons of the War in Ukraine for Western Military Strategy No. 242

- PESCO Armament Cooperation: Prospects and Fault Lines No. 241

- Rapprochement on the Korean Peninsula No. 240

- More Continuity than Change in the Congo No. 239

- Military Technology: The Realities of Imitation No. 238

- The OSCE’s Military Pillar: The Swiss FSC Chairmanship No. 237

About the Author

Anna Hess Sargsyan is a Senior Programme Officer at the CSS. Her work in Ukraine ranges from educational management to expert support to dialogue processes on different levels.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.