The Next Steps of North Africa´s Foreign Fighters

12 Mar 2018

By Lisa Watanabe for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published in March 2018 by the Center for Security Studies (CSS). It is also available in German and French.

Since 2011, thousands of people have left their countries to fight in Syria, Iraq, and beyond, for the most part in the name of Islamic State (IS). The group’s successes attracted an estimated 40,000 foreign fighters – a figure far higher than that for other major jihadi mobilizations, including those associated with the 1979 – 89 Afghan war, the 1992 – 5 Bosnian war, the war in Afghanistan since 2001, and Iraq following the US-led invasion in 2003. North Africans have made up a significant contingent of foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. However, the Levant has not been their only destination. They have also flocked to Libya following the creation of an IS enclave in the conflict-stricken country.

North African states are wrestling with how to deal with returning foreign fighters, as well women and children seeking to return from formerly IS-held territories. Other foreign fighters may redeploy, with Libya in particular likely to be a preferred destination for those fleeing Syria and Iraq, due to its weak governance and security structures and continued IS presence. North Africa is geographically close to Europe, and there are transnational links between jihadis in both regions, as became evident in the cases of the 2016 Berlin Christmas market and 2017 Manchester Arena attacks, which were both perpetrated by individuals with links to jihadist groups in Libya. Therefore, Europe can ill afford to ignore the challenges that the next steps of foreign fighters and returnees will pose to North Africa over the coming years.

Departing and Deploying

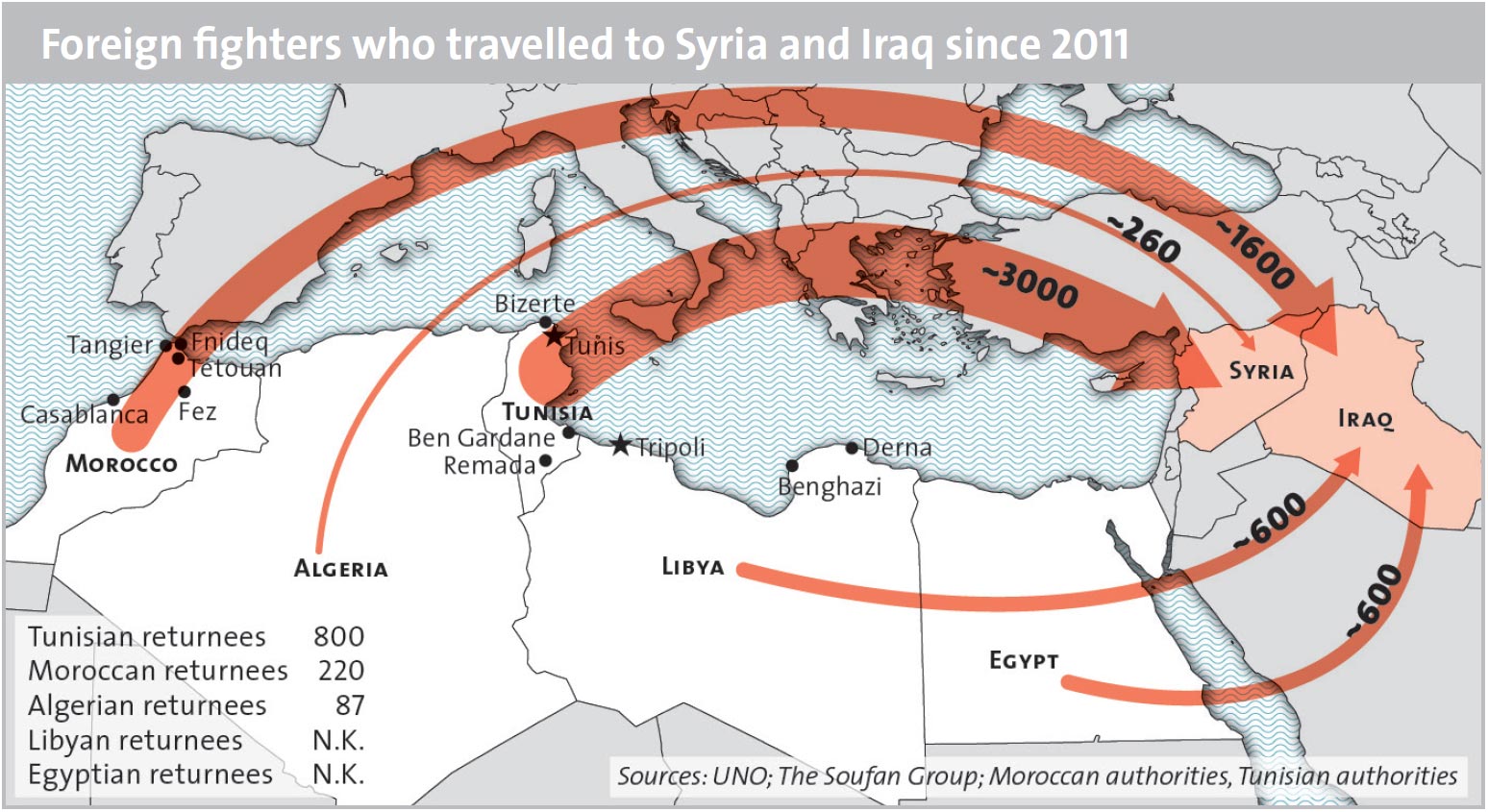

Jihadi foreign fighters may be loosely defined as individuals who travel to a state other than their own to participate in an insurgency within a conflict-afflicted state. While numbers are imprecise, due to delays in reporting and the absence of some official figures and subsequent reliance on estimates, they do help to give an idea of the scale of the problem. Over 3,000 Tunisians, some 1,600 Moroccans, and at least 600 Egyptians have travelled to Iraq and Syria. Although no official figures exist for Libyans, they were among the first to travel to Syria and Iraq, indicating that they too could have been present in fairly large numbers, some 600, according to estimates. Algerians have been present in markedly smaller numbers, 260 (as at December 2015).

North African foreign fighters have flocked not only to Syria and Iraq, but also to IS provinces within North Africa. Whereas Libya was once viewed as a transit and training hub for jihadis travelling to Syria and Iraq, it too became a destination state for foreign fighters from 2014 on. Ease of access to the country and the presence of an IS enclave in Libya made it an attractive destination, as well as a feasible alternative to the caliphate in the Levant as travel to Syria and Iraq became increasingly difficult. Some 1,350 to 3,400 foreign fighters are believed to have travelled to Libya since 2011. Tunisians have made up the bulk (1,000 – 1,500), joined by smaller numbers of citizens from other North African countries. North African foreign fighters have also joined the IS “Sinai Province” in Egypt, albeit in smaller numbers.

Recruitment appears to have been mainly carried out through people who are known to would-be foreign fighters, such as friends already in Syria or contacts within their local milieu, with online media playing only a secondary role. Established jihadi groups, such as Ansar al-Sharia Tunisia, Ansar al-Sharia in Libya, and Gema’a al-Islamiyya in Egypt, have also proven to be effective recruitment and facilitating networks. The personal nature of recruitment may help to explain why hotbeds of recruitment exist in major departure states, such as cities in northwestern Morocco (Fnideq, Tangier, and Tetouan), as well as Casablanca and Fes, Ben Gardane, Remada, Bizerte, and Tunis in Tunisia, and Tripoli, Derna, and Benghazi in Libya (see map). Some of these areas (Ben Gardane and Derna) have a history of radicalization and foreign fighter mobilization.

The routes taken to Syria and Iraq are by now well known to authorities. Many North African foreign fighters would have crossed over land from Turkey to reach Syria and Iraq. Some would have flown to Turkey, sometimes via a third country. Others would have crossed by sea to Turkey from Libya. Libya itself has been reached predominantly over land, often through towns such as Ben Guardane near the Tunisian-Libyan border or Debdeb on the Algerian-Libyan border. Some Egyptians have also flown from Cairo to Khartoum and then crossed over land from Sudan into Libya.

Reasons for becoming a foreign fighter are many and varied, resulting in no single identifiable profile. However, a number of factors do appear common to individuals who have become foreign fighters. These include a perceived duty to assist fellow Sunni Muslims in Syria; religious and ideological motivations, often linked to the notion of Syria as the location of the final battle between Muslims and “non-believers”; and a sense of social and economic injustice instilled by socio-economic marginalization in their home countries. Such push factors seem to have combined in complex ways with the promise of worldly gains, including salaries and wives, in IS propaganda, as well as a sense of perspective that is often lacking in foreign fighters’ home countries.

In addition to young men, a number of women have also migrated to IS-held territory in Syria and Iraq, as part of a broader mobilization linked to building a caliphate. Seven hundred Tunisian and an estimated 275 Moroccan women (roughly equivalent to 23 and 17 per cent of the amount of foreign fighters from these countries) are thought to have emigrated to the caliphate in the Levant. Women have also migrated to Libya, with Tunisian women amongst the largest cohort, numbering some 300, according to some estimates (equivalent to 20–30 per cent the figure for foreign fighters). Moroccan women also travelled to Libya, though it is unclear how many. Furthermore, children have accompanied their parents or were born in the caliphate and the IS province in Libya, although their numbers are as yet unknown.

Returning and Redeploying

Some foreign fighters have already returned to their countries of origin or residence in North Africa. Amongst those known to have returned are some 800 Tunisians, 220 Moroccans, and at least 87 Algerians (roughly 25, 13, and 33 per cent of the total number who left for Syria and Iraq, respectively). Given the strategic importance of Libya for IS, it is likely that a number of Libyan foreign fighters would have made the journey back to their homeland, though no official figures are available. In addition to those apprehended, many foreign fighters will have returned clandestinely, since returning through official ports of entry is now likely to result in arrest.

Judging by the countries through which they have transited or where they are currently stuck, it seems that the return routes are fairly similar to the ones they may have taken to reach their destinations. Tunisians have returned clandestinely by crossing over land from Libya, for example. Egyptians too have returned via Libya or Sudan. A number of Tunisians and Moroccans are currently stuck in Turkey as they try to make their way back, perhaps using the smuggling routes they may have initially taken to get to Turkey.

Those who have returned disillusioned or are heavily monitored by the security services in their home countries are unlikely to represent a grave risk. The most acute risks will be posed by the remainder, who may possess sophisticated skills and extensive networks and, in some cases, may even have been sent back home to continue the fight there. The IS enclave in Libya itself was established by Libyan foreign fighters who returned from Syria in 2014. While something similar is unlikely to be replicated elsewhere, some returnees could turn their attention to their home countries. Indeed, some Moroccan IS foreign fighters have already stated their intention to wage jihad against the monarchy.

Returning foreign fighters could not only have an impact on national jihadi networks, but also on regional ones. Regional jihadi networks could be reinforced by their return. Many North African returnees are likely to have been trained in Libya before travelling to Syria and Iraq. As a result, many may have jihadi contacts in Libya. Tunisians in particular have travelled in large numbers to Syria and Iraq and would most likely have trained and transited through Libya first, suggesting that the Tunisian-Libyan networks could be given a boost by their return.

Regional security may be further impacted by those who do not return home, but instead redeploy to the last remaining North African IS province – Sinai Province in Egypt – or to Libya, where IS is attempting to regroup. Indeed, numerous IS militants in Syria are believed to have already moved to Libya following military offensives against their movement’s heartland from 2015 on. The fall of IS strongholds in Syria and Iraq could increase that number. This would have implications not just for Libya, but also for its neighbors. Tunisia has already been heavily affected by the IS presence in Libya. The biggest 2015 terrorist attacks in Tunisia at the Bardo Museum in Tunis and the Sousse beach resort were carried out by individuals who had trained in Libya, and the attempted takeover of the border town of Ben Gardane in 2016 was planned by an IS cell based in the Libyan border town of Sabratha, for example.

Along with men, women and children have been fleeing IS-held territories. Some have made their way back home. Others are being detained in Libya, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, awaiting trial and/or repatriation. Women have not only had roles as wives and mothers, but also as moral enforcers and recruiters, and in Syria and Iraq, they have been used to carry out suicide missions. Some female returnees could, therefore, continue recruiting at home or engage in terrorist activities. Indeed, IS leaders have recently called upon female returnees to ready themselves for new missions that could include suicide attacks and raising their children to be future IS militants. While many children would have been too young to be trained in combat skills, reports have emerged of boys as young as nine being indoctrinated and taught to use weapons.

Policy Responses

Thus far, countries in North Africa have adopted an overwhelmingly legalistic approach to returning foreign fighters. In line with the 2014 UNSC Resolution 2178, which required countries to take steps to address the foreign fighter phenomenon, most countries (with the exception of Libya) now have legal frameworks for prosecuting returning foreign fighters, for the most part for having joined a terrorist group abroad. Therefore, returning foreign fighters who are detected at official ports of entry will face arrest. However, not all of those arrested will be prosecuted for a number of reasons, including lack of evidence and under-capacity criminal justice systems, which may make it difficult to compile evidence to bring people to trial.

In spite of the difficulties of prosecution, few countries in the region have adopted administrative measures to deal with returning foreign fighters for whom prosecution may not be feasible, but who may be suspected of having committed foreign fighter-related crimes. Tunisia is one notable exception, however. Those returning foreign fighters not being tried judicially are being held under house arrest and monitored, for example.

In addition, no de-radicalization or reintegration programs specifically tailored to returning foreign fighters appear to have been created, either inside or outside of prisons. While Moroccan and Tunisian governments have on occasion spoken of the possibility of establishing such programs, nothing concrete has yet transpired. In the Tunisian case, proposals to deal with returning foreign fighters that go beyond incarceration have tended to prompt a fierce reaction from civil society actors who insist on a tougher approach, preventing successive governments from following through on their proposals. However, in September 2017, the Tunisian government announced a new initiative to de-radicalize returning foreign fighters, though its fate has yet to be seen.

Locking up returnees without accompanying measures aimed at their de-radicalization and re-integration may prove short-sighted. Imprisoning returnees may provide ideal environments for them to radicalize and recruit others, particularly since some countries in the region have overcrowded prisons in which inmates may already harbor grievances against the state, making them susceptible to jihadi narratives. Moreover, some foreign fighters who have only arrest and imprisonment to expect on their return may decide that they have no choice but to move on to weakly governed and conflict-afflicted states and to rely on the support of jihadi networks, making their demobilization unlikely while increasing the risks associated with regional hotspots like Libya.

Countries in the region have yet to develop clear policies on how to deal with female returnees. Thus far, the information available suggests that while women detected upon returning are arrested, there may be a tendency to show them more leniency than male returnees, reflecting a broader propensity in the wider MENA region to view women as non-violent or as victims. Tunisian female returnees, for example, have been arrested, subsequently released, monitored, and given counseling through programs supervised by The Ministry of Women’s Affairs and Family. No defined policies appear to exist for the treatment of children who travel back with their mothers or orphans who may eventually be accepted by their parents’ countries.

Moving Forward

Given that individuals are likely to present different levels of risk, effective national strategies for dealing with returnees are likely to require a case-by-case approach. While some individuals may need to be imprisoned, others may be better dealt with outside the prison system. Such a differentiated approach would need to be accompanied by carefully designed de-radicalization and reintegration programs both inside and outside prisons. Mental health and social support structures will probably be needed in the case of children.

However, de-radicalization and reintegration will only be effective if returnees do not later encounter the same conditions that pushed them to leave their countries in the first place. The UN Action Plan on Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE) has called on states to address the conditions conducive to radicalization as part of their national PVE strategies, as well as ensuring that counter-terrorism activities take place within the rule of law. However, many governments in the region still have a long way to go to address direct (police brutality, indiscriminate arrests) and structural (political and socio-economic exclusion) causes of radicalization.

Reducing the regional impact of returning and redeploying foreign fighters will also require a coordinated regional approach to the problem, including greater cooperation between states in relation to border security and intelligence sharing, which is not as robust as it could be. Libya remains the weakest link in any such effort to deny jihadi militants a safe haven in the region. Concerted regional and international efforts to end the conflict in Libya and to build improve governance and security in capacities in the country are thus urgently needed.

Europe, including Switzerland, can support North African countries in their efforts to deal effectively with the challenges associated with returnees and redeploying foreign fighters by encouraging the exploration of de-radicalization and re-integration options, supporting progress on security sector reform and improvements in political and socio-economic inclusion, particularly amongst youths, as well as by standing united behind the UN political process in Libya and supporting Libya and supporting capacity-building in the country.

About the Author

Dr. Lisa Watanabe is a Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. Among other publications, she is the author “Algeria: Stability against All Odds?” (2017) and “Libya – in the Eye of the Storm” (2016).

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.