Instruments of Pain (IV): The Food Crisis in North East Nigeria

26 May 2017

By International Crisis Group

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageInternational Crisis Groupcall_made on 18 May 2017.

Overview

The humanitarian crisis in north east Nigeria is at risk of growing worse. Almost five million people in the region (8.5 million across the wider Lake Chad basin) are facing severe food insecurity. This primarily is a result of a seven-year-old insurgency by Boko Haram, an Islamist militant group, which provoked forced displacement as well as massive infrastructure destruction. But the Nigerian military’s forceful counter-insurgency strategy also was a precipitating factor. Amid this situation, aid agencies are unable to access many of those in need due to security constraints and lack sufficient funding for 2017. They warn that emergency food rations may be cut in weeks, just as the lean season approaches for the vulnerable millions.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that “more than 20 million people in South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and north-east Nigeria are going hungry, and facing devastating levels of food insecurity”. As Crisis Group has argued in its three prior briefings in this series, preventing communities from tipping into famine clearly requires donors to immediately increase their contributions; in Nigeria’s case this means both honouring previous pledges and committing more to fill the 2017 funding gap. But politics lies at the core of any serious response.

As a priority, Nigeria’s government will have to step up and demonstrate greater commitment to providing relief to its own citizens, managing the provision of food and other humanitarian aid more judiciously and with greater accountability, and phasing out military restrictions on some economic activities in Borno state, crucial to resuscitating the region’s agriculture and overall economy. Securing access could require breaking a taboo and negotiating directly with Boko Haram. “Longer term, of course, the answer lies in a more comprehensive strategy for ending the insurgency: the army cannot on its own guarantee security and failure to provide other basic public goods and visible socio-economic dividends to affected areas risks derailing recent progress against Boko Haram. Moreover, as this crisis is directly the result of a man-made conflict, the Nigerian government must now explore all options for ending the conflict, including negotiating peace with the insurgents.

Conflict, Displacement and Food Crisis

The food crisis in north east Nigeria (and across neighbouring Lake Chad basin countries, Cameroon, Chad and Niger), currently Africa’s largest humanitarian emergency, has its roots in the conflict with Boko Haram that began in 2010. Over the last seven years, fighting has caused the deaths of more than 20,000 people and displaced almost two million, with another 200,000 fleeing to neighbouring countries. Since 2015, a rejuvenated Nigerian military and a four-nation Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF) – including the armies of Cameroon, Chad and Niger operating around the Lake Chad basin – have pushed Boko Haram to the eastern fringes of Borno state, along the mountainous border with Cameroon, and around Lake Chad. But the insurgency is resilient and much of the region remains insecure.1

Three main factors aggravated the crisis. Foremost was Boko Haram’s attacks on rural communities that forced many to flee. Second was massive destruction of economic infrastructure in Borno state and other parts of the north east caused by the fighting. The government’s response to Boko Haram also played a part: the Nigerian military often forced civilians to flee areas where it conducted counter-insurgency operations, either to minimise civilian casualties or prevent locals from collaborating with insurgents. It, and neighbouring regional militaries, also banned or restricted trade in goods and services in an attempt to deny Boko Haram supplies and revenue, a practice that further decimated the region’s economy. Combined, these factors led to a situation in which a huge population simply became unable to feed itself.

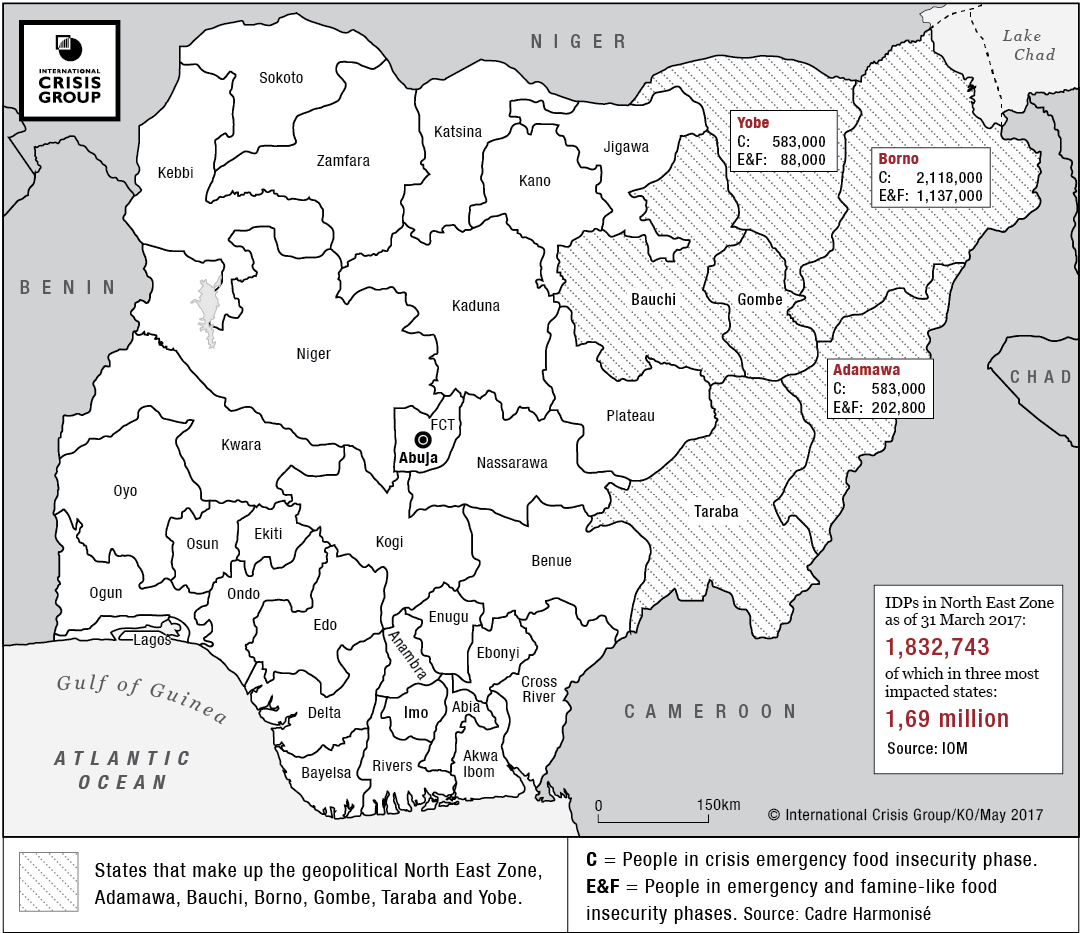

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) reported that 4.7 million Nigerians in the north east now urgently need food assistance, including 1.4 million facing an “emergency” and 38,000 famine-like conditions.2 All told, in the north-eastern Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states, an estimated 5.2 million people could face severe food insecurity by mid-2017, with 450,000 children under the age of five suffering severe acute malnutrition.3

A. Plummeting Food Production

As farmers, herders and fishermen fled or were forcefully uprooted from their communities, agriculture became a major casualty of the violence. The situation was aggravated as thousands of young and able-bodied men, crucial for farm labour, were either killed by Boko Haram or fled both the insurgents and the military. In Borno state, the insurgency’s epicentre, staple cereal production plummeted between 2010 and 2015 – sorghum by 82 per cent, rice by 67 per cent and millet by 55 per cent.4 Today, the state, which used to produce about a quarter of Nigeria’s wheat, grows none. Oluwashina Olabanji, the Lake Chad Research Institute executive director, said that wheat production across the entire North East Zone (comprising Borno and five other states) “has declined to just 20 per cent of what it used to be due to the insurgency”.5

Livestock production also is ruined. The Al-Hayah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria (ACBAN) reported that as of February 2016, 1,637 members were killed, and over 200,000 cattle, sheep and goats, as well as 395,609 sacks of food items lost in insurgents’ attacks in Borno state.6 Beginning in December 2014, the fishing industry suffered a similar fate as Boko Haram stepped up attacks on communities around Lake Chad.

B. A Massive Displaced Population

The conflict has led to the internal displacement of almost two million individuals within Nigeria, with an additional 200,000 Nigerians living as refugees in neighbouring countries.7 This large population survives solely thanks to humanitarian assistance provided to internally displaced persons (IDPs) camps or to the benevolence and charity of communities where they take refuge. The region’s Fishermen’s Association chairman, Abubakar Gamandi, told Crisis Group:

The majority of the farmers and fishermen are now in internally displaced [per-sons] camps. Men and women who once produced food, fed their families some-times including numerous dependents, have now been reduced to beggars, depending on others to provide for them.8

Military activities, particularly the internment of large rural populations in camps (eg, Bama) or city-sites (eg, Banki, Gamboru-Ngala) that have fled areas of conflict since 2014, exacerbated the food situation.9 These camps, which largely rely on food supplied by the military as well as national or state emergency management agencies, were poorly resourced until international humanitarian organisations got involved in 2016. As an aid worker noted, “confining the IDPs in these camps and denying them freedom of movement also worsened their misery”.10

C. Decimated Regional Economy

The food scarcity, initially due to plummeting production and massive displacement, was compounded by the destruction of economic infrastructure and the military’s restriction of several key economic activities in large sections of Borno state. Fighting destroyed 30 per cent of houses, water sources, roads and bridges in the area, crippling agriculture and other economic activities. Road closures and curfews further restrict trade and livelihoods. The army also banned trading in fish from Lake Chad, movement of foodstuff, sale of vehicle fuel and fertiliser, as well as transportation by motorcycle, justifying such measures as short-term steps to choke the insurgents.

In some cases, the argument seemed unassailable. For instance, the army banned the sale of fertiliser on the ground that it is a key ingredient for making Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs). Likewise, it proscribed the sale of fish in towns near Lake Chad because Boko Haram’s levies on Nigeria-Niger cross-border fish traders had become an important source of funding. But there is a cost. Prolonged enforcement of such bans and restrictions has prevented large numbers of people from earning money, aggravating the earlier miseries caused by direct attacks and human displacement.

A Deficient National and International Response

Responses by both international actors and the government have been lacking. In large part due to relatively patchy local and international reporting on the Lake Chad basin crisis – as compared, for example, to humanitarian emergencies in Syria or South Sudan – international actors were slow to either recognise its gravity or respond. Some prospective donors almost certainly assumed oil-rich Nigeria was capable of managing the challenge; however, with the fall in oil prices from late 2014 onwards, coupled with sabotage of domestic production by Niger Delta armed groups through much of 2016, the country’s economy slumped into recession.

Other factors likely explain the insufficient reaction: longstanding concerns about Nigeria’s corruption and lack of accountability; President Muhammadu Buhari’s claim that humanitarian agencies were exaggerating the situation to boost their own fortunes;11 the Nigerian government’s rejection of UN Security Council debates on the insurgency and reservations about humanitarian support (borne out of its unpleasant experience during the late 1970s Biafra war);12 and, more broadly, local conservative sensitivities toward the influx of foreign, chiefly western, aid workers. The international response thus started slowly, lagging far behind needs. As a diplomat summed up, “we had a paradox: one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises was struggling for the world’s attention”.13

The international response picked up in 2016, leading some organisations to expand their food aid programs. The UN World Food Programme (WFP) raised the number of monthly beneficiaries from 200,000 in October 2016 to more than one million people in March 2017.14 Still, assistance fell short of growing needs. In early 2017, UN assistant secretary-general and lead humanitarian coordinator for the Sahel, Toby Lanzer, observed that only 53 per cent of the $739 million required under the 2016 Humanitarian Response Plans for Nigeria and other Lake Chad basin countries was funded.15

Subsequently, in an effort to mobilise a broader response in 2017, a UN Security Council mission toured the Lake Chad basin region and urged stronger international response.16 The governments of Norway, Germany and Nigeria, in partnership with the UN, organised a humanitarian conference on Nigeria and the Lake Chad region on 24 February 2017. The Oslo Humanitarian Conference drew pledges of $672 million from fourteen donors and raised global awareness of the crisis. Yet even that did not come close to bridging the estimated $1.5 billion now needed in the region.17

What is more, only $458 million of the pledged amounts were targeted for humanitarian action in 2017, while the remaining $214 million was for 2018 and beyond. As of late April, the World Food Programme reported receiving a mere 20 per cent of its 2017 funding requirements.18 OCHA also reported that, as of 30 April 2017, only 17.2 per cent ($182 million) of the 2017 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) for north east Nigeria had been funded and that additional funding is urgently required to continue to scale up the humanitarian response.19

The funding gap is not the only challenge. Food aid delivery is seriously hampered by insecurity. Despite the government’s repeated claims to have degraded and decimated the insurgency,20 aid workers assess that roughly 80 per cent of Borno state, along with parts of Adamawa and Yobe states, still present high or very high risks for humanitarian agencies’ operations.21 On 28 July 2016, the UN briefly suspended aid deliveries after insurgents attacked a UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) convoy between Borno state capital, Maiduguri, and the town of Bama, injuring a UNICEF employee and an International Organization for Migration contractor. In some areas purportedly under government control, the army’s effective hold largely is confined to local government headquarters; with continued military “clearance operations”, the security situation remains too risky for aid workers in several localities. As a result, food aid delivery is weakest where the food situation is most dire.

About 25 per cent of IDPs found refuge in officially-designated IDP camps or other camp-like sites. The other 75 per cent have moved into host communities (chiefly spread across Borno, Adamawa, Yobe, as well as Bauchi and Gombe states).22 The latter are difficult for the government and aid agencies to track and locate. Moreover, the federal government has failed to prioritise their needs. Together, this means that food is not reaching large numbers of people in need, including some of the most vulnerable. While the government periodically has sent grains to IDPs – releasing them from the national strategic reserve – and despite additional aid from the Presidential Committee on North-East Initiatives (PCNI) and the Victims Support Fund (VSF), supply has been neither consistent nor sustained. Many inhabitants of the region question the government’s claim that it has spent over $2 billion in humanitarian assistance for the north east in 2016 as displaced and vulnerable populations have yet to experience any commensurate relief.

Nigeria’s bureaucracy and corruption also impede aid delivery with visa restrictions to international aid personnel coming into the country and sluggish customs processes for clearing imported supplies.23 There have also been cases of food trucks diverted to unknown destinations and of food consignments stolen by camp and local officials.24

The net result of delayed and inadequate funding, pervasive insecurity, poor and unreliable distribution, as well as governmental red tape and corruption is plain: as of April 2017, only 1.9 million of the 5.2 million or a mere 37 per cent of the population at risk of severe food insecurity was being reached.

Risks of a Failed Response

The inability to sustain, let alone expand, food and other humanitarian aid would have devastating consequences. In many communities that humanitarian aid workers presently cannot reach, famine looms. Without sustained food delivery, many people will starve to death; a larger number will die from disease. As the rainy season sets in, beginning in May, illnesses are more likely to spread, especially within IDP camps, and those lacking in food will be at even greater risk. Among the survivors will be thousands of stunted children, a burden for the region’s future development.

There could be security consequences as well. Without sufficient food in the camps to sustain them, tens of thousands of IDPs and refugees already are seeking to return home to take advantage of the rainy season and farm and fend for themselves.25 A hasty, hunger-driven return to insecure areas could expose them to Boko Haram attacks and overwhelm the army’s ability to provide security.

A deteriorating situation likewise could increase trans-Saharan migration to Europe’s shores. Nigeria already ranked as the third largest source of migrants crossing the Mediterranean in 2016; most of those fleeing are economic migrants from the country’s south, not conflict refugees, but a prolonged food crisis in the north east could add to the migrant flow. Nigeria’s chief humanitarian coordinator, Ayoade Olatunbosun-Alakija, warned: “The world could see a mass exodus from a country of 180 million people if support is not given, and fast”.26

Millions of severely deprived, undernourished and displaced youth seeking food and other forms of sustenance represent not only a humanitarian disaster but also potentially a longer-term risk for the region’s stability. They could turn to bandit groups, be engaged by local politicians to fight electoral rivals or recruited by extremist jihadist groups. Borno state Governor Shettima pointedly warned: “If we fail to take care of the 52,000 children orphaned by Boko Haram, then we must get ready that 15 years down the road, they will come back to take care of us”.27

What Needs to be Done

The most immediate step the international community could take to prevent a slide toward famine is to support ongoing food programs and expand their coverage. That would entail honouring pledges made at Oslo and by the UN Security Council mission that visited Lake Chad basin countries in early March 2017 to assess the humanitarian situation but also mobilising additional resources to fill the almost $1 billion funding gap in 2017.28 Urgent and timely disbursement also is crucial; this in turn will require aid agencies and their local partners to coordinate more closely, share information on access routes as the rains set in, and augment local storage capacities in anticipation of greater supplies.

Rolling back the food crisis also requires the government to demonstrate greater commitment to providing relief to its own citizens by:

- Avoiding the indiscriminate use of force that fuels displacement and prevents aid agencies from delivering food on a sustainable basis or from expanding their reach, even as it maintains military and vigilante operations against insurgents, and also restores civil authority in liberated areas of the north east.

- Focusing on improving security in communities to which formerly displaced persons have returned, allowing them to restart farming and other economic activities.

- Exploring what heretofore its counter-insurgency strategy has not contemplated, namely the option of negotiating with willing Boko Haram factions to allow access to people aid agencies have been unable to reach and who number an estimated 700,000.

- Scaling up provisions for food aid and other emergency needs, while ensuring that distribution is more transparent, accountable and targeted to areas where displaced communities have returned in order to facilitate economic recovery and reduce reliance on food aid.

- Maintaining military pressure on Boko Haram, but also using a more holistic strategy to defeat the insurgents by demobilising militants, solving local conflicts, reinvigorating the economy and reestablishing administrative services, including justice and security, as well as economic projects and infrastructure.

As the present food crisis was caused by an armed conflict, its ultimate solution lies in resolving that conflict. Military operations against Boko Haram represent only one option toward ending the violence. Following the precedent set by negotiations that resulted in the release in October 2016 and May 2017 of over 100 kidnapped school girls, the Nigerian government must also now explore the option of a negotiated end to the entire conflict.

Appendix A: Nigeria – Food Insecurity in North East

Notes

1 For earlier reports on Boko Haram and the conflict, see Crisis Group Africa Reports N°s 168, Northern Nigeria: Background to Conflict, 20 December 2010; 216, Curbing Violence in Nigeria (II): The Boko Haram Insurgency, 3 April 2014; and 244, Watchmen of Lake Chad: Vigilante Groups Fighting Boko Haram, 23 February 2017; Africa Briefing N°120, Boko Haram on the Back Foot?, 4 May 2016; and Africa Commentary, North-eastern Nigeria and Conflict’s Humanitarian Fallout, 4 August 2016.

2 In Borno state, 1,099,000 people, or 19 per cent of the population, are currently facing “emergency” food insecurity (large food consumption gaps resulting in very high acute malnutrition and excess mortality) and 38,000 facing “famine” (extreme lack of food and/or other basic needs even with full employment of coping strategies; starvation, death, and destitution evident). In Adamawa state, 197,000 people are in emergency and 5,800 in catastrophic phase; in Yobe state, 88,000 are in emergency. “North East Nigeria: Food Security and Nutrition Crisis”, Assessments Capacity Project (ACAPS), 12 April 2017.

3 “Nigeria – North-East: Humanitarian Emergency. Situation Report No. 10”, UNOCHA, 30 April 2017.

4 A new variety of wheat introduced by the government in 2012 and which promised to triple the average yield could not be planted in Borno because most of its wheat-growing areas were either occupied by, or within deadly reach of, the insurgents. “Boko Haram conflict cuts Nigeria’s wheat crop as farmers flee”, Bloomberg, 20 April 2017.

5 “Boko Haram conflict cuts Nigeria’s wheat crop as farmers flee”, op. cit. The geopolitical North East Zone comprises Adamawa, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Taraba and Yobe states.

6 Crisis Group interview, Alhaji Ibrahim Mafa, chairman, Al-Hayah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria, Maiduguri, 24 October 2016.

7 The number of IDPs has declined slightly as military gains against Boko Haram have enabled some to return: UNOCHA reports that, as of 31 March 2017, 1,832,743 persons (326,010 households) remain displaced in the six North East Zone states. “Nigeria – North-East: Humanitarian Emergency. Situation Report No. 8 (as of 31 March 2017)”, UNOCHA, 12 April 2017.

8 Crisis Group interview, Maiduguri, 18 October 2016.

9 Crisis Group Commentary, North-eastern Nigeria and Conflict’s Humanitarian Fallout, op. cit.

10 Crisis Group email correspondence, aid worker based in Maiduguri, Borno state, 3 May 2017.

11 “Buhari accuses UN, others of exaggerating crisis in North-east Nigeria”, Premium Times (www.premiumtimesng.com), 4 December 2016.

12 During the civil war (1967-1970), the government prohibited trade with Biafran separatists. Humanitarian agencies then smuggled in goods to prevent civilians from starving, but similar means were used to bring in arms.

13 Crisis Group interview, Western diplomat, Abuja, 22 April 2017.

14 “Scaling Up Food Assistance in Northeastern Nigeria”, U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), 5 April 2017.

15 “Europe ignores Nigeria humanitarian crisis at its peril, warns top UN official”, The Guardian, 31 January 2017.

16 “UN Security Council says North East Crisis most neglected”, Business Day, 7 March 2017.

17 “Oslo Humanitarian Conference for Nigeria and the Lake Chad region raises $672 million to help people in need”, press release, UNOCHA, 24 February 2017.

18 “Insecurity in the Lake Chad Basin – Regional Impact, Situation Report No. 25”, World Food Programme, 30 April 2017.

19 “Nigeria – North-East: Humanitarian Emergency. Situation Report No. 10”, op. cit.

20 “Boko Haram not in control of any Nigerian territory, Army insists”, Premium Times, 24 September 2016; “Boko Haram substantially degraded, says Gen. Abubakar”, Vanguard, 26 September 2016; “Defence Minister insists Boko Haram largely degraded”, Today, 17 December 2016; “Nigeria Boko Haram: Militants ‘technically defeated’ – Buhari”, BBC, 24 December 2015; “Nigeria: Boko Haram is crushed, forced out of last enclave”, AP, 24 December 2016; “Boko Haram not occupying Nigerian territory – defence minister”, Channels Television, 22 April 2017.

21 Crisis Group interviews, Abuja, 20 and 27 April 2017.

22 Crisis Group interview, National Emergency Management Agency official, 20 April 2017.

23 Crisis Group interview, aid worker, Abuja, 19 April 2017.

24 Crisis Group interviews, displaced persons, civil society leaders, Maiduguri, October 2016. See also, “Borno IDP camps: Rising hunger as officials divert food”, Daily Trust, 17 July 2016; “How officials steal food meant for people displaced by Boko Haram, IDPs narrate”, Premium Times (www.premiumtimesng.com), 5 October 2016; “Court jails two Borno LG officials for selling IDPs’ rice”, The Punch, 5 May 2017.

25 Crisis Group telephone interview, IDP camp administrator in Maiduguri, 22 April 2017.

26 “World must aid famine-threatened Nigeria to avoid ‘mass exodus’”, Reuters, 18 April 2017.

27 Lecture at 40th Anniversary of late General Murtala Mohammed’s assassination, Abuja, 13 February 2017.

28 The UN Nigerian Humanitarian Response Plan seeks $1.05 billion. As of late April, 15.3 per cent was funded.

About the Organization

The International Crisis Group (ICG) is an independent, nonprofit and nongovernmental organization that works to prevent and resolve deadly conflicts.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.