Russian Analytical Digest No 226: Russia and the Balkans

6 Dec 2018

By Dimitar Bechev and Branislav Radeljić for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 6 November 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Kremlin.ru external page(CC BY 4.0)call_made

Russia’s Influence in Southeast Europe

By Dimitar Bechev, Center for Slavic, Eurasian and East European Studies, University of North Carolina

DOI: <10.3929/ethz-b-000301365>

Abstract

Russia has emerged as a key player in the international politics of Southeast Europe, as well as an adversary of the West. Moscow wields disruptive influence by exploiting indigenous grievances and conflicts. Its principal assets are its connections to Balkan political, economic and societal actors, who, as a rule, pursue their own objectives and are not beholden to the Kremlin. At the end of the day, Russia lacks the power to roll back EU and NATO influence in the region.

Russia’s involvement in Balkans has become a hot topic in both the European Union (EU) and in the US. Countless policy papers, newspaper articles and political speeches point at the threat of a conflict between the West and Moscow tearing the region apart. The most recent example of Russian meddling in local affairs comes from Macedonia, a country on the cusp of entering NATO and starting membership negotiations with the EU. Russia has been blamed by politicians and pundits alike for seeking to sabotage the socalled Prespa Agreement, which settles the long-standing dispute with Greece over the name Macedonia. Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has been criticising the former Yugoslav republic’s decision to change its name to “North Macedonia” as a Western diktat. Zoran Zaev, the Macedonian prime minister, accused the Russian-Greek businessman Ivan Savvidi of bankrolling radical groups opposed to the rapprochement with Greece. In an unprecedented move, the Greek government, usually well disposed to Moscow, expelled two Russian diplomats last July, and denied entry to two more.1 Senior Western officials who have been shuttling to Skopje of late, like US Defence Secretary James Mattis, have been raising concern about Russian meddling.2

Russia has many partners and fellow travelers across Southeast Europe. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, it has forged a common cause with Republika Srpska’s leader Milorad Dodik, now the elected Serb member of the state’s tripartite presidency. Serbia’s President Aleksandar Vučić has been a frequent guest at the Kremlin too. Even his Croatian counterpart Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović, formerly a top NATO official, as well as a staunch critic of Russia’s “hybrid warfare” in Bosnia, has reached out to Vladimir Putin, as have Bosnian Croat leaders too.3 In Bulgaria, another EU member, Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and President Rumen Radev are attempting to outbid one another in their criticism of Western sanctions against Russia. Balkan governments continue to lobby Moscow for energy projects, such as the proposed extension of the TurkStream gas pipeline into the EU. While Bulgaria, along with Greece, refused to expel Russian diplomats in response to the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in March 2018.4

This article begins by discussing Russia’s strategy towards Southeast Europe. Then it looks at the region’s response. Lastly, the paper discusses three key areas where Moscow wields influence: security affairs, the economy, and within local societies.

Russia’s Strategy

In strategic terms, Southeast Europe lies beyond what Russia’s claims as its sphere of interest in the former Soviet Union. However, Russia sees Southeast Europe as a weak spot on the EU periphery, vulnerable to its influence. From the mid-2000s onwards, Moscow has sought to co-opt local actors (political elites, business leaders, parts of civil society) into implementing ambitious ventures, such as the South Stream pipeline. The growing confrontation with the West after Putin returned to the Kremlin in 2012, and particularly following the annexation of Crimea in March 2014, transformed the Balkans into an arena of competition. While Russia does not have the resources to roll back EU and US influence in the region, it is in a position to disrupt it. It does so by leveraging its links with like-minded actors, including anti-Western opinion makers, parties, activists and civic organizations with nationalist orien- tations. Such connections give Moscow an advantage in the broader contest with the West. And, from a relatively limited investment, Russia is getting a great deal of geopolitical mileage. The very fact that Russia is the focus of everyone’s attention as a direct competitor to Western power is an achievement in and of itself.5

The Region’s Perspective on Russia

With some notable exceptions (Romania, Kosovo, the Bosniak community, Albania), Southeast Europe looks at Russia as a potential ally and/or source of economic benefits. Moscow has historical and religious links to the region. Geography plays a part too. Russia is an immediate neighbour, and therefore poses a military threat to Romania and Bulgaria, but the countries of the former Yugoslavia and Greece are removed from the Black Sea littoral. The post-2014 military build-up in Crimea is not of direct concern. Perceptions of Russia are also informed by actor’s attitude to the West. Pro-EU and NATO constituencies are highly critical. Conversely, nationalists, conservatives and the far left, who are critical of Western powers and the US in particular, welcome Russia as a counterweight to Brussels and Washington.

What ultimately defines the Balkan countries’ policy towards Russia is the pragmatic bent of their political elites. For them, links to the West, as represented by the EU and NATO, remain a top priority. Yet, Russia is viewed mostly as a source of economic opportunities and, occasionally, as an ally on key political issues (e.g. Serbia aligning with Russia over Kosovo from 2008 onwards). It is true that Russia’s changing posture has amplified the threat perception of late. Its actions in Montenegro, where the authorities link Moscow’s security services to a coup attempt in 2016 and to attacks on the rapprochement between Greece and Macedonia, are a case in point. Nonetheless, the majority of Balkan countries have a preference for engagement over containment when it comes to Russia.

The Security Dimension

Unlike NATO and the EU, Russia is not a direct stakeholder in Balkan security. While it sits on some diplomatic bodies, such as the Peace Implementation Council (PIC) in Bosnia, it has no boots on the ground. It withdrew its peacekeepers from the former Yugoslavia in 2003. At the same time, Russia plays an indirect role. A defence cooperation agreement from 2013 has broadened ties with Serbia. The two armies have been training together on a regular basis. Having joined the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization CSTO) as an observer, Belgrade hopes to modernize its military with Russian help. After lengthy negotiations, in 2016, Russia donated six surplus MiG-29 fighter jets, 30 T-72 tanks and 30 BRDM-2 armoured reconnaissance vehicles. Yet, Serbia is simultaneously pursuing military-to-military cooperation with NATO, a fact which remains underreported in the media loyal to President Vučić.6

Russian security agencies have a foothold in the region. For instance, the Military Intelligence Directorate (GRU), the outfit blamed for the hacking of the Democratic National Committee’s server in the run-up to the 2016 presidential election and the Skripals’ poisoning, was in all likelihood behind an attempt to assassinate Montenegro’s then Prime Minister, Milo Djukanović and derail the country’s entry into NATO.7 In the aftermath of the arrests made in Montenegro, Nikolai Patrushev, head of the Russian Federation’s Security Council and former director of the Federal Security Service (FSB), landed in Belgrade for talks with then Prime Minister Vučić.8 There have been allegations by the Greek government about Russian security operatives working to block the rapprochement with Macedonia and halt NATO enlargement. Last but not least, there have been long-standing suspicions about connections between senior Bulgarian officials and business leaders and Moscow, on account of their affiliation with the communist-era secret police, which, at the time, reported to the Soviet security apparatus.

Russia is involved in some of the outstanding disputes over sovereignty in the former Yugoslavia. Moscow’s seat in the PIC has allowed it to provide diplomatic cover to Milorad Dodik’s brinkmanship tactics and threats to pull Republika Srpska out of Bosnia via an independence referendum.9 Russian diplomats have engaged with Bosnian Croats, who also pose a challenge to the state’s constitutional structure. Without giving separatism a blank cheque, Moscow is ensuring Bosnia remains dysfunctional and internally divided. Russia’s role in Kosovo is not as central as previously, because the dispute between Belgrade and Pristina is now mediated by the EU and not the UN. However, the Kremlin has been encouraging, both publicly and behind the scene, Serbian nationalists, in order to counterbalance the West. But, that does not mean that Russian policy cannot be flexible and adapt to changing circumstances. For instance, Putin offered his support to Vučić and Kosovan President Hashim Thaçi’s initiative to settle the dispute through a negotiated partition.10 The discussions between Belgrade and Pristina had already been given their blessing by the Trump administration in the US and by the EU officials.

Russia’s Economic Footprint

In economic affairs, Russia lags far behind the EU. However, as a report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) observes, “Russian companies in [Central and Eastern Europe] have tended to be concentrated in a few strategic economic sectors, such as energy and fuel processing and trading, whereas EU countries have a more diversified investment portfolio that spans different manufacturing subsectors.”11 According to the authors, Russian investment represents a full 22 percent of GDP in Bulgaria and around 14 percent in Serbia. Oftentimes, Russian investment reaches the region through Europe, with the Netherlands, Austria, and Cyprus as gateways.12

Energy occupies a special place in Russian economic activities in Southeast Europe. Major Russian firms, such as Gazprom, GazpromNeft and Lukoil, dominate the oil and gas markets in the region. Their role grew exponentially in the 2000s. In 2008, for instance, Serbia decided to sell a controlling stake in its national oil company NIS (Naftna Industrija Srbije) to Gazprom-Neft, Gazprom’s oil branch. Lukoil owns Bulgaria’s sole refinery near Burgas, the largest in Southeast Europe outside Greece and Turkey. Lukoil Neftochim is the biggest company in the Bulgarian market and controls the wholesale and retail market. It has large presence in Serbia and Macedonia as well.13 Although it is a private company unlike Gazprom, Lukoil depends on the Kremlin’s good graces and therefore can easily be turned into a foreign policy tool.

Balkan countries have been eager to benefit from Russian infrastructure projects. In 2006–2014, Bulgaria and Serbia joined South Stream, with Bosnia’s Republika Srpska and Macedonia coming onboard too. They are currently hoping to be part of TurkStream 2 (TS2). Greece, Macedonia and Serbia, for instance, are championing the TESLA pipeline extending TS2 into Central Europe. Bulgaria lobbies for the so-called Balkan Hub project that would be fed by gas from TS2, as well as form Azerbaijan and indigenous production in the Black Sea.14 At the same time, all Balkan countries are eager to diversify their energy supplies away from Russia and extract better commercial terms from Gazprom. For instance, Greece is already building the Transadriatic Pipeline (TAP), inaugurating the much-discussed South Gas Corridor linking consumers in Europe to the Caspian. Bulgaria and Serbia are working on connecting their grids with their neighbours to allow alternative imports. There are also projects for liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals that are being advanced by Greece and Croatia.

Russia’s Influence on Societies

Russia and Vladimir Putin enjoy popularity in many quarters of Southeast Europe. This reflects historical memories and perceptions of cultural proximity. But, what is also at play are deep-held grudges against the West. The scars of the Yugoslav Wars in the 1990s are still visible and are often exploited by politicians. As in other parts of Europe, Russia’s anti-Western messaging capitalizes on themes such as the fear of refugees, and Islamophobia more broadly, the economic hardship experienced by local societies, and opposition to LGBT rights. Russia casts itself as a champion of traditional values and national sovereignty.

Russian influence flows through a variety of channels, formal and informal. An example of the former is the local branch of the Sputnik news agency in Serbia, with a regional outreach mission. Mainstream media, including TV channels and the popular print outlets, provide positive coverage too. In general, the deteriorating media environment in large swathes of the Balkans (low journalistic standards, a lack of ownership transparency and political interference) is fertile ground for Moscow’s strategic communications or propaganda, depending on how one sees it.

The results are easy to see. A Gallup survey from 2014, funded by the European Commission, showed that Serbian citizens saw Russia as a leading donor, several notches ahead of the EU. In reality, the EU and its member states have spent €3.5 billion in Serbia alone since 2000. Russia’s contribution is hardly a tenth— mostly loans rather than grants—and lags behind that of the United States and even Japan. In Bulgaria, a survey by pollster Alpha Research, from March 2015, found that 61 percent of citizens held a positive view of Russia and 30 percent had a negative view. At the same time, nearly two-thirds of respondents stated they would vote for the EU and NATO in a putative referendum about whether Bulgaria should stay as a member and only one-third for alignment with Russia and other post-Soviet states. According to a Greek poll from October 2015, citizens see the EU as their main ally, with Russia much lower down the list (44 percent against 12 percent). However, when asked about individual countries, respondents ranked Russia second in popularity after France, and well ahead of Germany and the US. Overall, 58 percent are favourable towards Russia and 34 percent unfavourable.15

Pro-Russian sentiments do not necessarily mean the countries in question are likely to “pivot” away from the West. But, they do make it easier for politicians to hedge their bets and, to borrow an expression from a senior US diplomat involved in the Balkans, sit on two chairs. In addition, Russia holds an advantage in the pursuit of influence by media campaigns because, in many cases, it is preaching to the converted.

Conclusion

Russian influence in Southeast Europe is shaped by both supply and demand. Moscow has cultivated links to the region, in order to balance and compete against the West. But equally, local players have been keen to exploit their relations with Russia to achieve their own goals: maximize economic rents and enhance political clout. However, Russian influence is not without limits. Montenegro’s accession to NATO illustrates that. Moscow’s response has been low-key. The Russian Federation imposed a no visa regime (which would have hurt its own nationals residing or owning vacation property along the Adriatic coast). The economic countermeasures enacted by Moscow are not far reaching, in comparison to those adopted in either post-Soviet cases, like Ukraine or Georgia, or against Turkey in 2015–6. Russia will suffer another setback if Macedonia joins NATO next year. Yet, Russian influence will not simply wither away. So long as favourable local conditions—weak institutions and state capture, nationalism, resentment against the West—persist, Russia will remain part and parcel of Balkan politics.

Notes

1 Tensions escalate between Greece and Russia, with Macedonia in the middle, New York Times, 19 July 2018.

2 U.S. Defence Secretary warns of Russian meddling in Macedonia, Reuters, 16 September 2018.

3 In October 2017, Grabar-Kitarović’s three-day visit to Russia culminated in talks with Putin in his Sochi residence. She was seen at Putin’s side during the World Cup 2018 final played between Croatia and France in July 2018.

4 By contrast, non-EU countries in the region, such as Albania and Macedonia, did expel Russian diplomatic personnel, as did Romania and Croatia.

5 Dimitar Bechev, Rival Power. Russia in Southeast Europe, Yale University Press, 2017.

6 Serbia signed an Individual Partnership Agreement (IPAP) with NATO in January 2015. In 2016, the army has carried out 200 joint activities with NATO and the US, as opposed to just 17 with Russia. See Damir Marušić, Damon Wilson and Sarah Bedenbaugh. Balkans Forward: A New Strategy for the Region, Atlantic Council, November 2017.

7 The trial in Montenegro concerning the coup attempt is still ongoing. 8 Dimitar Bechev, The 2016 Coup Attempt in Montenegro: Is Russia’s Balkans Footprint Expanding, Foreign Policy Research Institute, April 2018. Patrushev has been characterised as “the curator” of Russia’s Balkan policy. See Mark Galeotti, Do the Western Balkans Face a Coming Russian Storm?, European Council on Foreign Relations, April 2014.

9 Dodik enjoys well-publicized links to Russian nationalists, such as the oligarch Konstantin Malofeev, who is on the Western sanctions list, because of his sponsorship of the paramilitaries which initiated the so-called Russian Spring in the Donbas in 2014. See Christo Grozev, The Kremlin’s Balkan Gambit: Part I, Bellingcat. March 2017.

10 That happened after talks at the Kremlin on 2 October. See “Putin, Vucic discuss “further steps” on Serbia-Kosovo deal”, Bloomberg, 2 October 2018.

11 Heather Conley et al. The Kremlin Playbook: Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe, CSIS, October 2016, p. 11.

12 A case in point is Agrokor, Croatia’s largest company accounting for full 16% of national GDP owes €1.3 bn to the Austrian subsidiaries of Sberbank and VTB.

13 On Russia’s economic influence in the Western Balkans, see Martin Vladimirov et al. Assessing Russia’s Economic Footprint in the Western Balkans, Center for the Study of Democracy (Sofia), January 2018.

14 The Bulgarian government is hoping to restart the nuclear power plant at Belene, a project implemented by Rosatom, which was frozen in 2012 due to the lack of funding.

15 Bechev, Rival Power, Chapter 8.

Further Reading

Dimitar Bechev, Rival Power. Russia in Southeast Europe, Yale University Press, 2017

James Headley, Russia and the Balkans. Foreign Policy from Yeltsin to Putin, Hurst, 2008.

Martin Vladimirov et al., Assessing Russia’s Economic Footprint in the Western Balkans. Corruption and State Capture Risks. Center for the Study of Democracy, January 2018.

Maxim Samorukov, Russia’s Tactics in the Western Balkans, Carnegie Europe, November 3, 2017.

Wojciech Ostrowski and Eamonn Butler (eds.), Understanding Energy Security in Central and Eastern Europe: Russia, Transition and National Interest, Routledge, 2018.

About the Author

Dr. Dimitar Bechev is Research Fellow at the Center for Slavic, Eurasian and East European Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Russia and Serbia: Between Brotherhood and Self-Serving Agendas

By Branislav Radeljić, University of East London, UK

DOI: <10.3929/ethz-b-000301365>

Abstract

Since the early 1990s, Russia’s standpoint towards the Balkans and Kosovo in particular has largely reflected Serbia’s position. However, while it opposes external interventions and insists on the principle of territorial integrity in the case of Serbia, Moscow has been primarily concerned with the strengthening of its own position in European affairs and from this point of view, the Kosovo question has perfectly served such an ambition.

In recent decades, the Balkan region has represented an excellent opportunity for Russia’s external engagement with and reassertion of its relevance in post-Cold War Eastern Europe, with Moscow’s influence over the former Warsaw Pact states having been diminished due to their accession to NATO and the European Union. During the Yugoslav drama of the immediate post-Cold War years, Russian representatives attended the ceremony proclaiming the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, offering their support to this new state established by Serbia and Montenegro in 1992. Later, during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Russia was a member of the Contact Group, formed in 1994 to deal with the war, and while it kept condemning the fighting, it also opposed its Western colleagues who were determined to use force against the Serbs. This was not an easy task, especially when it became clear that many of the acts of violence were being orchestrated by the regime of Slobodan Milošević. Towards the end of the 1990s, during the escalation of the Kosovo crisis and consequent NATO intervention, Russia insisted that the Kosovo question be approached as a Serbian internal issue, leaving Serbian sovereignty intact, in accordance with the UN Security Council Resolution 1160, adopted in March 1998.

Following the Kremlin’s inability to prevent the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia, with some perceiving it as a direct insult to its efforts (a view shared by numerous Russian and Serbian officials at the time), Kosovo and the wider Balkan region came to be ranked high on Russia’s foreign policy agenda. Even after the war came to an end and the UN Security Council Resolution 1244 had been adopted, Russia’s mistrust of the West’s response to Kosovo continued. The Russian Federation was welcomed to take part in KFOR [NATO-led Kosovo Force] within the framework of the NATO-Russia Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security; however, Moscow considered that this only provided Russia with scope for a rather limited presence as compared to NATO. This inferiority complex triggered the decision in Moscow to send troops to Priština international airport, occupying it before the arrival of the previously authorized NATO troops. Despite its peaceful outcome, this incident confirmed the Russian leadership’s concerns about the future position of the Serbian population in Kosovo under the foreign supervision, but even more importantly, the Kremlin’s concerns with its own reputation at home and within the international system.

In contrast to the West, which was concerned with the still-in-power Milošević regime, but also expected that it would need to come up with a common position regarding the status of Kosovo, Moscow stuck to its previously adopted standpoint—simply put, the West made a terrible mistake in the case of Kosovo. Putin, soon after being elected President of Russia in March 2000, approved an official Foreign Policy Concept of the Russian Federation, which among other interests and priorities, stipulated that Russia was in favor of a just settlement in the Balkans and the preservation of territorial integrity, and not Kosovo’s independence. In Serbia, following the overthrow of Milošević, the country’s new president Vojislav Koštunica, expressed appreciation for the Russian approach; during his own visit to Moscow in late October, Koštunica welcomed Russia’s interest in the region, stating that its presence was necessary for a greater balance of European, Russian and US forces. In return, some months later, Putin visited Belgrade, reconfirming Russia’s support for Serbia’s territorial integrity. And again, while the international community was struggling to identify a durable solution for Kosovo and the region—be it in the form of the failed 2003 “standards before status” approach, requiring Kosovo to properly democratize, or the failed 2005–2007 Vienna talks, when it became obvious that none of the two conflicting parties were ready to compromise— the Russians seemed the most relaxed of the other counterparties. They believed that the promoted policy of Kosovan independence contradicted the sections of UNSC Resolution 1244 that related to Serbian territorial sovereignty, making the talk of status pointless. Moreover, the Russian authorities insisted that the decision on Kosovo should be of a universal character and that the portrayal of the Kosovo as a unique case was yet another attempt by the West to circumvent international law—an approach confirming the existence of inconsistencies or double standards within the international community. Even when Moscow joined the Contact Group on Kosovo, together with Brussels and Washington, aimed at furthering the negotiations on the future status of Kosovo and seeking to achieve a mutually acceptable solution, the Russian side still insisted on the preservation of Serbia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.

When the Kosovo Albanian leadership adopted a resolution, proclaiming independence from the Republic of Serbia in February 2008, the position of Russia was once again in stark contrast to the one adopted by the dominant Western powers, who rushed to recognize the new state. For example, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs stated that, in addition to violating Serbian sovereignty, the Kosovan authorities ignored the UN Charter, Resolution 1244, the Helsinki Final Act, and so on. Putin characterized the act as a terrible precedent with unavoidable consequences for the international system, and soon-to-be President, Dmitry Medvedev proclaimed that what Iraq was to the United States, Kosovo was to the EU. Understandably, the Serbs welcomed the Russian approach, which went even further in mid-April 2009, when the Russian state submitted a long statement to the International Court of Justice, outlining its arguments as to why Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence was not in accordance with international law. In fact, the support continued, becoming the highlight of official visits and diplomatic exchanges between Belgrade and Moscow. On different occasions, Medvedev and the Russian Ambassador to Serbia, Aleksandr Konuzin tried to assure the Serbs that the painful Kosovo problem was also in the hearts of all Russians. And, when Putin visited Serbia in March 2011, in addition to confirming Russia’s willingness to support its southern Slavic brothers in the energy and financial spheres, he also stressed that Russia would support Serbia’s Kosovo policy.

By this point, it had already become clear that too many official disagreements surrounded the Kosovo question. Both the Serbs and the Kosovo Albanians only put forward a plan A as an option, meaning that one side would exit as an absolute winner and the other as an absolute loser. The international community played an important role in the formation of both sides uncompromising approach, due to the obvious differences between its actors. In contrast to 1992, when both the then European Community and all twelve of its members recognized Slovenia and Croatia as independent states, the situation was more complicated two decades later, leaving Kosovo in a truly unfavourable position. The EU was not united around the Kosovo settlement (since five of its member states—Cyprus, Greece, Romania, Slovakia and Spain—had refused to recognize Kosovo’s independence), meaning that both the Kosovo Albanian and Serbian leaderships expected even greater support from individual players with a clear-cut position, namely the US and Russia. The prospects for interdependence and partnership between Belgrade and Moscow grew further in 2012, when Tomislav Nikolić, the founder and first president of the Serbian Progressive Party (a party formed in 2008 by Nikolić and Aleksandar Vučić, the former Deputy President and General Secretary, respectively, of the ultranationalist Serbian Radical Party) entered the Serbian political scene as the new President. Putin congratulated him, inviting friendship and mutually beneficial cooperation between the two states, and Nikolić chose Moscow for his first visit abroad. Although it was said to be an informal meeting, this visit opened numerous questions about the politics of alternatives and new opportunities, and whether the new Serbian leadership, contrary to their electoral campaign, was going to minimize its links with the West and move more towards the East. Indeed, Nikolić made clear in Moscow that the only thing he loved more than Russia was Serbia and announced that Serbia would never join NATO.

As would be expected, the Russian military intervention in Ukraine and the consequent annexation of Crimea in March 2014 encouraged all sorts of questions about the similarities between the cases of Kosovo and Crimea, and the contradictions and inconsistencies characterizing Russia’s approach towards the notion of territorial integrity were widely commented upon. Putin was heavily criticized by numerous Western officials, whose views he tried to discredit by calling them cynical and beyond double standards. However, the Crimean question has revealed that Russia was ready to pursue its own geopolitical interest by assisting Ukraine’s disintegration. Following the outbreak of the Ukrainian crisis, the Serbian leadership did not side with the EU’s decision to introduce sanctions against Moscow, but has adopted a neutral position. This represents an attempt to show respect towards Russia, but is also a position that is acceptable for Brussels, so that Serbia’s integration with the European Union would not be compromised. Still, the presence of Serbian volunteers supporting pro-Russian forces in Crimea—support that is inspired by their shared Orthodox faith, Russia’s advocacy in the case of Kosovo and, more generally, anti-Western views— encouraged more debate about how Belgrade manages this balancing act between Moscow and Brussels, and thus about Serbia’s overall direction. When Putin visited Belgrade in October, numerous words of mutual appreciation were exchanged, with claims that Russia and Serbia see each other as their closest ally. Indeed, whenever the two sides have interacted either in Belgrade or Moscow, the message has been the same, with Russia promising to back Serbia’s claim to Kosovo.

The trajectory of the Russian–Serbian relationship outlined above has been further strengthened by the two countries’ mutually supportive political regimes. They both oversee a privatization of the state, a process facilitated by mounting corruption and state-generated propaganda. While using every opportunity to stress that they are working in the best interests of their respective peoples, so that many members of the public will continue to express their admiration for the ruling elite. The two regimes have sought to maximize their power even if this has implied widespread fearmongering, through threats, prosecution and the total exclusion of critics. Accordingly, issues around freedom, democratic change and societal transformation, bear no relevance on Russian–Serbian relations. Although it is understandable that the EU cannot do much about the highly problematic semi-authoritarian aspects of the Russian regime, it does come as a surprise that such practices have been tolerated in the Balkans. In fact, more and more voices have argued that the rise of President Vučić has, in fact, weakened the support for the EU in Serbia, because it has revealed the EU’s hypocrisy towards its core principles and values, such as the rule of law and human rights. Many from the intellectual elite, who have firmly advocated for EU accession in the past, are now disenchanted with the EU’s lack of reaction to Vučić’s alleged undermining of democratic principles. Vučić and his closest associates are known for sending out mixed messages. On the one hand, they have declaratively supported EU values, pledged their support for EU accession and so on. Whilst, on the other hand, the slightest external criticism from the EU has resulted in a narrative that the West wants to overthrow Vučić, that big powers are working against Serbia and that Russia makes for a more honest and reliable friend.

Finally, the continuous support from Russia has also provided the Serbian authorities with greater bargaining power and capacity to balance its relations with Moscow and Brussels, so that they can secure economic and political benefits from both sides (as a part of the EU membership negotiation process and by good access to Russia’s natural resources). In return, Moscow’s policy of amity and cooperation with Belgrade has not only served the position of Serbian official policy within the international community, it has also served the interests of the Russian leadership, which has gained greater presence in and relevance vis-a-vis the growing uncertainties characterizing the EU’s policies and the overall European integrationist project. The obvious fatigue faced by the Brussels administration in relation to the messy case of Kosovo (due to the ever-popular secessionist debates within some of its member states, even though they did not object to the previous NATO action, such as Spain) represents an additional incentive for the Russian leadership to insist on the rightness of its own uncompromising view and thus to reinforce its place in European affairs.

Further Reading

Radeljić, B. (2017) Russia’s Involvement in the Kosovo Case: Defending Serbian Interests or Securing its Own Influence in Europe? Region: Regional Studies of Russia, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia 6(2), 273–300.

Radeljić, B. and Mehmeti, L. I. (Eds) (2016) Kosovo and Serbia: Contested Options and Shared Consequences, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Radeljić, B. (2014) Official Discrepancies: Kosovo Independence and Western European Rhetoric. Perspectives on European Politics and Society 15(4), 431–444.

About the Author

Branislav Radeljić is Associate Professor of International Relations at the University of East London, UK.

Opinion Poll

Friends and Foes of Russia

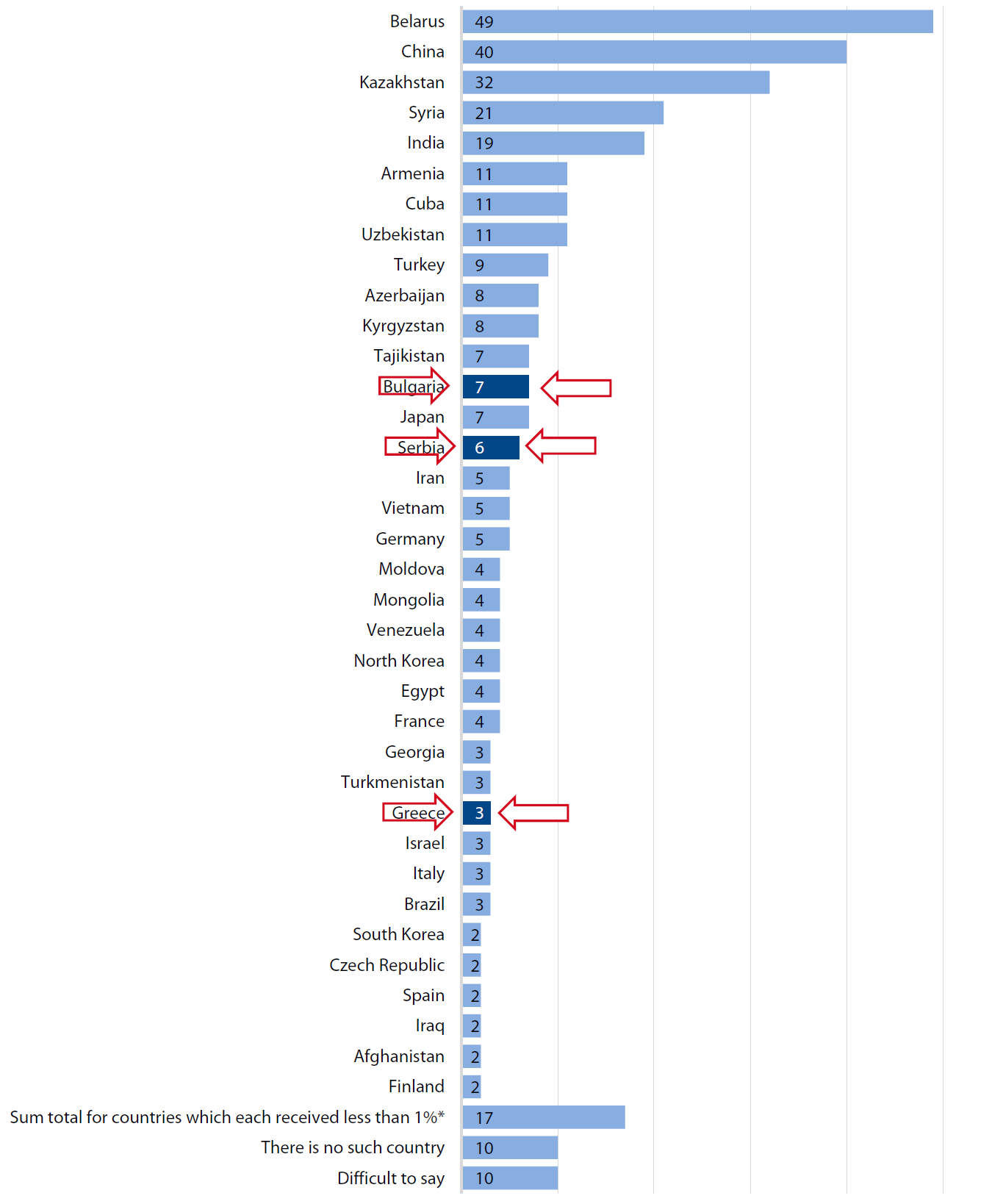

Figure 1: Name Five Countries Which You Would Consider the Closest Allies and Friends of Russia

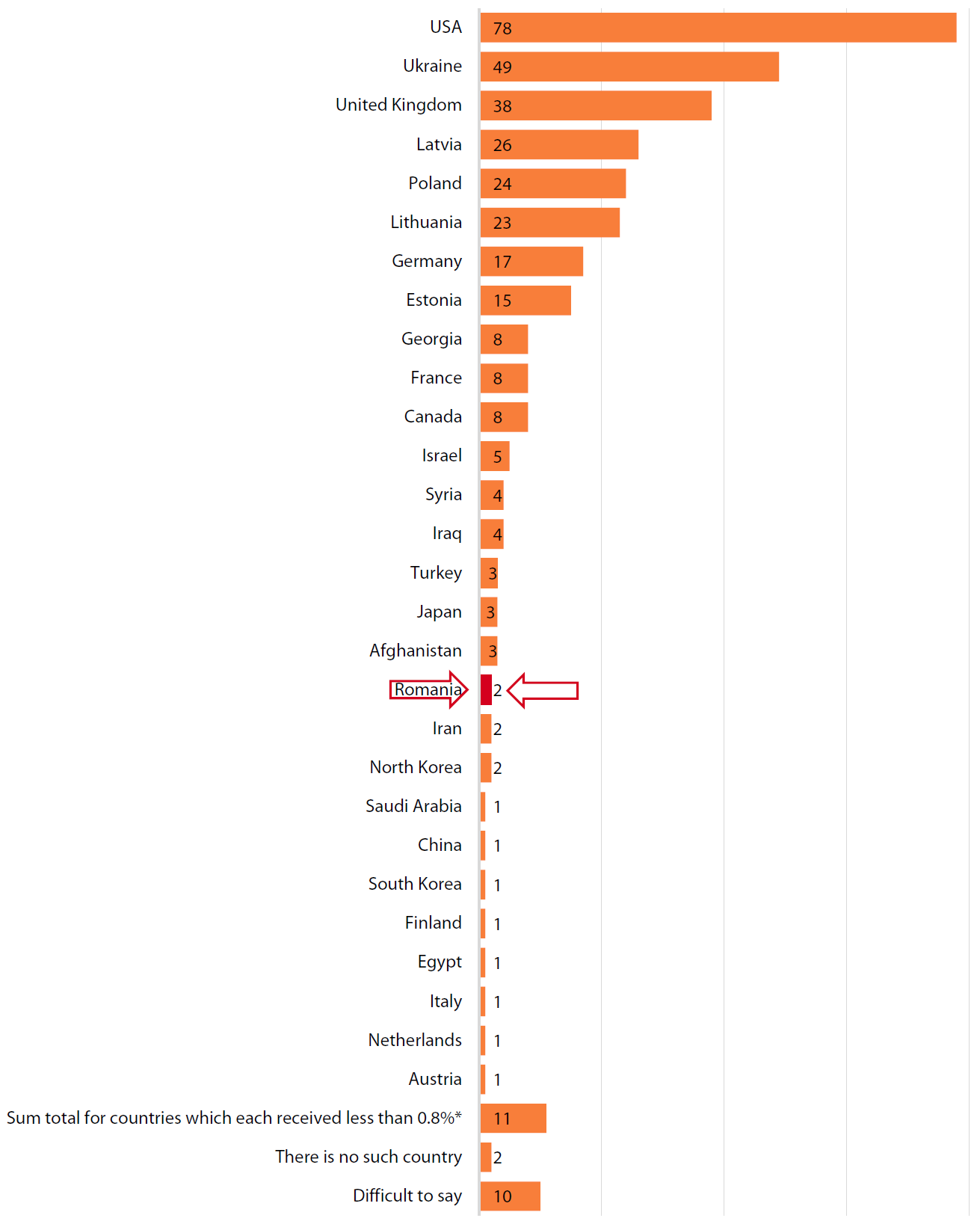

Figure 2: Name Five Countries Which You Would Consider the Worst Enemies of Russia

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.