Long-distance Relationships: African Peacekeeping

7 Dec 2018

By Stephen Aris and Kirsten König for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This CSS Analyses in Security Policy was originally published on 5 December 2018 by the Center for Security Studies. It is also available in German and French.

Long-distance Relationships: African Peacekeeping

The United Nations is continually searching for ways to manage the ever increasing demands to provide peacekeeping operations (PKO). When new crisis situations emerge, the UN often struggles to raise the resources, capabilities or political will to deploy an effective PKO in response. As a result, the UN has increasingly turned to the idea of working with other actors in joint, hybrid or coordinated PKOs. Most notably, the UN works with Regional Organizations (RO), as mandated by Chapter VIII of its Charter. These partnership arrangements aim to share the resource and capability burden facing the UN. Furthermore, endorsement from relevant ROs serves to strengthen a UN PKO’s political mandate and chances for long-term success. UN PKOs are authorized by the UN Security Council (UNSC), where oftentimes the voices of the actors with the greatest stakes in a particular crisis are sidelined. Collaboration with ROs, therefore, provides UN PKOs with greater “local” political legitimacy, participation and investment.

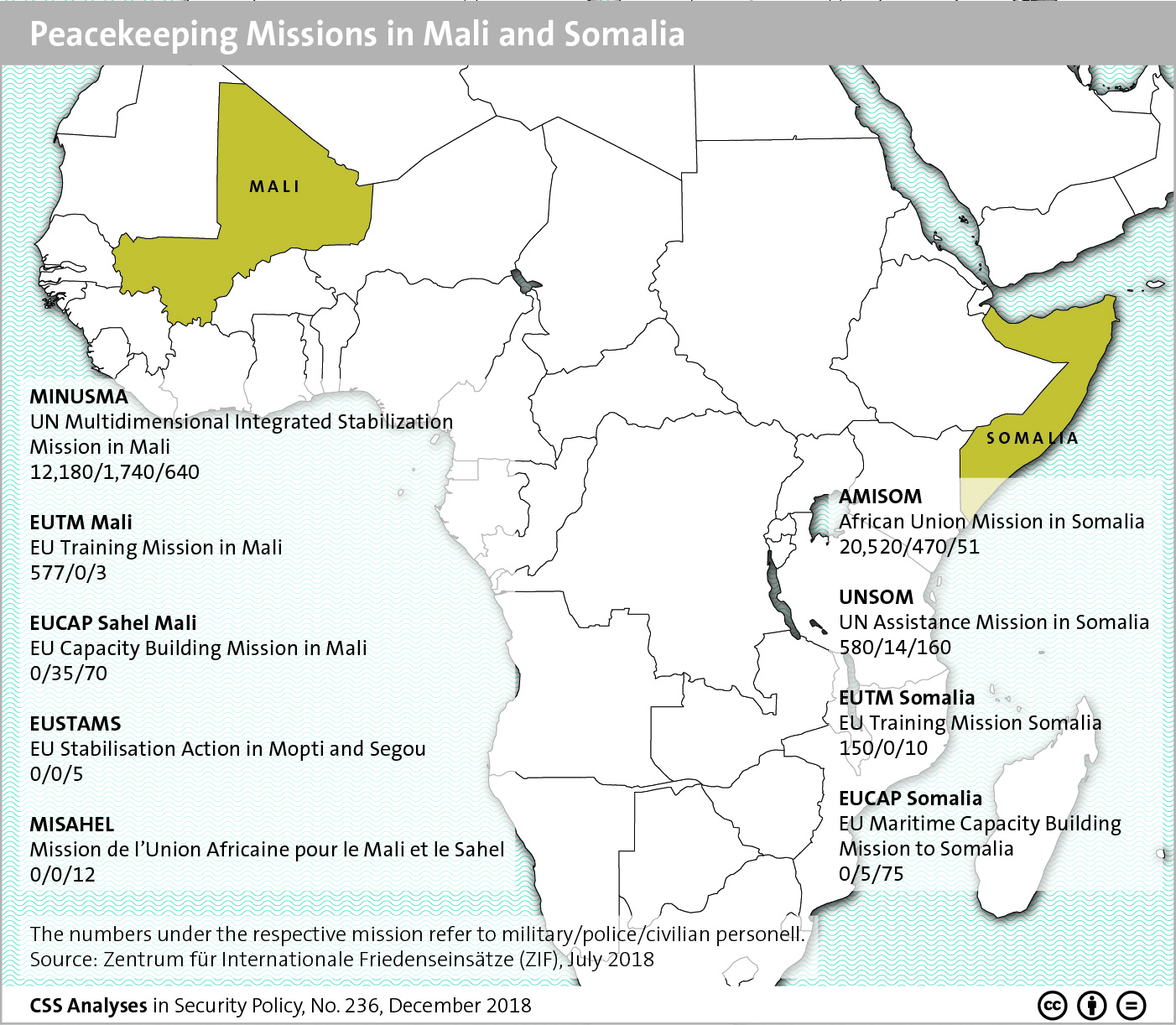

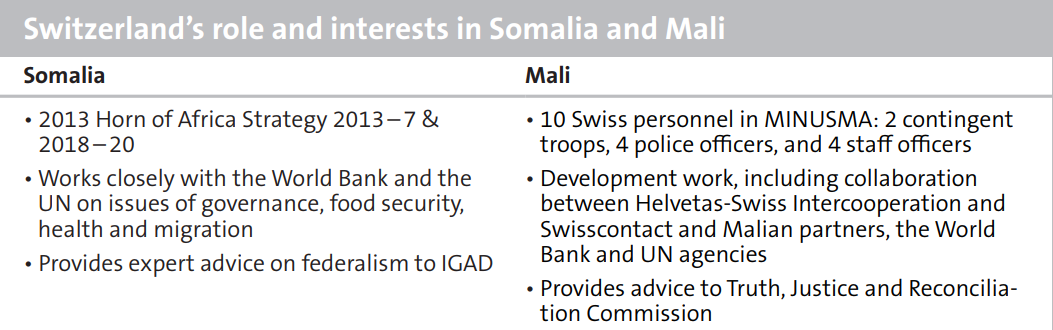

While expressing its desire to collaborate with multilateral organizations in all regions of the world, the UN has been most engaged in such partnerships in Africa. This is partly a reflection of need. Currently, half of the 14 peacekeeping operations led by the UN are on the African continent, and half of all ongoing conflicts the Uppsala Conflict Data Program classifies as wars are to be found in Africa. Since the mid-2000s, the UN and African Union (AU) have been actively developing a partnership. This relationship represents the only formalized partnership between the UN and a RO. The UN runs a permanent Office to the AU, and several joint strategic documents have been signed in recent years, setting out a framework for sustained collaboration between the two organizations. The UN’s Department of Political Affairs currently lists 18 contexts in which it is working together with the AU on conflict prevention and peacekeeping in Africa.

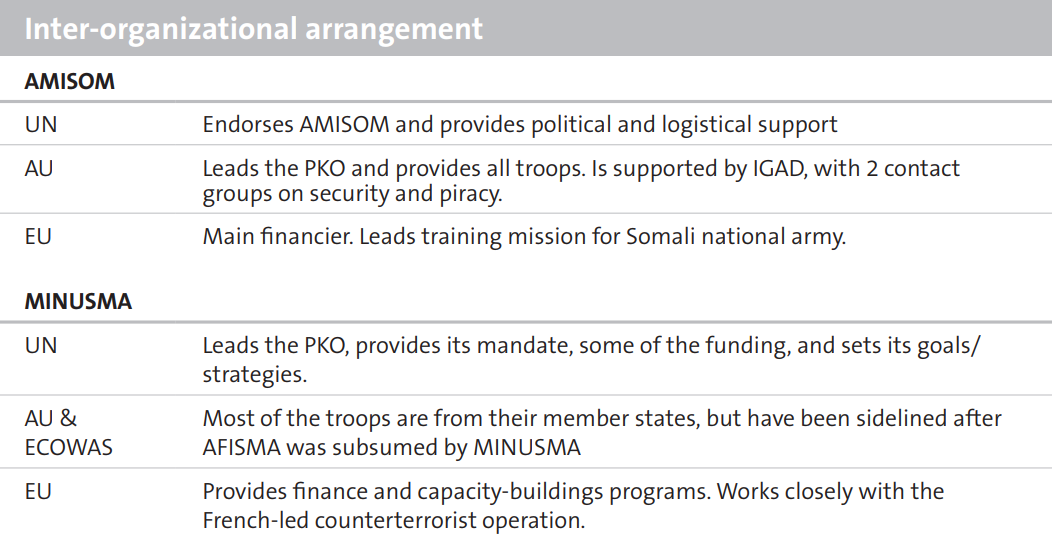

At the same time, this collaborative relationship between the UN and the AU has not been able to overcome one of the main challenges facing UN peacekeeping. African ROs often contribute troops and other capabilities to UN PKOs. They, however, often lack the financial resources required to sustain these PKOs. As a result, several collaborative UN-AU PKOs have turned to the EU to provide financial support. In this way, a tripartite, or sometimes quadripartite, arrangement has emerged between the UN, the AU and/or a sub-regional African RO, and the EU as a model of interorganizational peacekeeping in Africa. A typical allocation of roles and division of labour is that the UN provides a mandate endorsed by the international community, as well as bureaucratic support. African ROs offer the operation “regional” legitimacy and experience, as well as the backbone of personnel to conduct the operation. The EU meanwhile supports the operation financially and provides expert training to enhance the capabilities of the peacekeeping force.

On paper, this inter-organizational arrangement represents an elegant redistribution of the burden of and responsibility for managing security crises in Africa. However, relationships between organizations rarely function so smoothly in practice. Indeed, UN-RO partnerships open up a range of new challenges for both African peacekeeping and international peacekeeping in general.

First, cooperation with a RO requires the UN to make a political choice about who represents and can speak for a region. For example, the AU criticized the Western members of the UNSC for not listening to the regional voice by ignoring their plan for a political solution to the Libyan civil war in 2011, and instead arguing that the Arab League’s endorsement of their “no-fly zone” represented regional support. Hence, working with a RO has potential implications for the UN’s self-proclaimed commitment to impartiality, by potentially embroiling it in political disputes between competing ROs.

Second, almost all inter-organizational relationships are beset by ongoing tussles over the division of labour, whose mandate takes priority, and who will play the lead role. The 2017 UN Secretary-General report “on options for authorization and support of African Union peace support operations” amounted to a tacit recognition that collaboration between the UN and AU to that point had been largely informal and ill-defined, resulting in uncertainty and disagreement about these issues. Third, while the pooling of resources and capabilities is one of the main incentives for the UN and ROs to work together, this leaves open the question of what happens should one choose to end their participation in the PKO. Is it sustainable for PKOs to be dependent on multiple players, and their differing levels of commitment to resolving the security crisis?

Two of the most high-profile examples of UN-AU-EU peacekeeping collaboration shed light on these political and operational challenges: Somalia and Mali.

Somalia: AMISOM

The African Union-led PKO AMISOM was launched in response to developments in Somalia’s longstanding civil war during the mid-2000s. Following a failed attempt by the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), a regional organization in East Africa, to form a “peace enforcement” mission and the unilateral intervention of Ethiopian troops to prevent the collapse of the transitional government, AMISOM was mandated and deployed by the AU. This PKO was quickly granted UNSC authorization by the unanimous adoption of Resolution 1772, a mandate that has been renewed annually since 2007. Hence, AMISOM represents an inter-organizational peacekeeping arrangement in which the lead role is played by the RO, with the UN acting as a background partner. This distribution of roles was not based on mutual agreement at the start. The AU had envisioned that the overall responsibility for and lead role in the PKO would be handed over to the UN after a few years. This never happened. The UN lacks the political will to take over responsibility for a PKO on the ground in Somalia, in no small part due to the legacy of the failed UN PKO in the 1990s that caused considerable damage to its reputation. Furthermore, the UN has expressed its reservations about the AU’s “peace enforcement” mandate for AMISOM, with the UN reluctant to run a PKO based on such an active engagement approach. The UN does, however, contribute more to AMISOM than boosting its legitimacy by passing supportive resolutions. It operates politico-bureaucratic and logistical support programs.

In light of the UN’s refusal to take over responsibility for its operation, AMISOM grew significantly from 2007 to become the AU’s most costly PKO, with the largest troop deployment in its history. However, the AU lacked the resources to sustain such a huge deployment from the beginning. The UN has provided various support packages and funds over the years, but AMISOM has largely been reliant on other external donors. One of the most prominent is the EU. This funding comes mainly from the EU’s African Peace Facility program, part of the European Development Fund. Most significantly, EU funds have paid the salaries of the peacekeepers. This promise of a regular income works as an important incentive for the participation of troops from East African countries. In addition, the EU has played a notable role in supporting the goals of AMISOM, through the EU training mission for the Somali national army and the EU capacity building program, as well as extensive anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia. In other words, the EU stepped in to play an invaluable role in filling a financial and expertise void at the heart of AMISOM.

This, however, leaves AMISOM largely dependent on the EU. This situation does not tally with the idea that inter-organizational PKOs would serve to empower ROs to deliver globally-endorsed, but locallyinformed solutions to security crises. The extent to which the PKO is dependent on EU finance is evident by the accelerated timetable for AMISOM’s withdrawal from Somalia. From 1 January 2016, the EU decided to reallocate how its funds are used within Somalia. As a result, payments to AMISOM peacekeepers were reduced by 20 percent. The money cut was reallocated to aspects of the PKO other than peacekeepers salaries, with the EU arguing that it was time to prioritize a handover to the Somali army. AMISOM tried and largely failed to lobby the UN and other external donors, such as the US and the Gulf states, to cover the loss of EU funding for its peacekeepers. One year later, UN Resolution 2372 endorsed an AMISOM plan to draw down its role in Somalia by December 2021. This reduction in EU funding for AMISOM peacekeepers and a hastened plan for withdrawal are directly related.

It is highly questionable whether AMISOM is being drawn down because it has successfully completed its mission goals. Many analysts suggest that the Somali army – currently half the size of the AMISOM deployment – will not be ready to take full responsibility for maintaining security by 2022. There are continued large-scale al-Shabaab attacks in Somali cities and regular clashes continue to threaten stability. The US intensified drone strikes against militant targets. Nonetheless, a switch in the priorities and funding contribution of one of the key partners in the inter-organizational arrangement supporting AMISOM has had a big impact on the long-term outlook, goals and sustainability of the operation.

Mali: MINUSMA

The Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) is a notable UN-led PKO in a number of respects. It is one of the only PKOs to, one, have a “robust” peacekeeping mandate, two, involve troops from European countries, and three, to operate in parallel to an “antiterrorist” operation conducted by other external actors. It is also an example of a UNRO peacekeeping arrangement that differs from the one that emerged in Somalia. In Mali, the UN did step in to take over a PKO led by African ROs, namely the AUECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) joint PKO AFISMA. In contrast to Somalia, it is the UN that plays the lead role in, funds and has overall responsibility for the operation, while the African ROs are background partners. After a coup in March 2012, ECOWAS, the AU and the UN each advanced strategies for restoring constitutional order and bringing the conflict in Northern Mali under control. This led to Resolution 2085, in which the UN endorsed the African-led AFISMA, and charged the AU and ECOWAS with leading the PKO. However, due to disputes between the two organizations over the leadership of the PKO, its deployment was delayed. In the meantime, a new offensive against government forces in Northern Mali triggered a French-led military intervention, to which the UNSC also granted its approval. Subsequently, AFISMA operated alongside this French-led operation that also involved troops from African states.

However, at the request of the Malian transitional government and the UN, AFISMA was subsumed by the UN-led MINUSMA in the second-half of 2013, only six months into the one-year mandate granted to it by Resolution 2085. Both the AU and ECOWAS consented to this “rehatting” arrangement. However, the AU’s Peace and Security Council did so on the condition that this UN PKO would be given a “robust” mandate and that both the AU and ECOWAS would be consulted on and play an important role in the evolution of MINUSMA. By the time of the transition, the AU was already expressing its reservations that African ROs were being sidelined by the UNSC and European actors.

In a further sign of departure between the two PKOs, the Nigerian contingent of troops that formed the backbone of AFISMA did not continue to serve in Mali under MINUSMA. Nigeria is the dominant player in ECOWAS, and the withdrawal of its troops was a signal of a change in focus between the two PKOs. As a UN operation, MINUSMA has been able to call on troop contributions from countries outside of Africa, including notable contingents from China, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden.

In 2017, the UN endorsed the French-led counterterrorist “Operation Barkhane”, which involves the deployment of troops from the Sahel 5 group (Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, and Niger). One of its key roles is to combat the insurgency in Northern Mali. Even before then, MINUSMA had been operating in collaboration with the French-led mission. The more interventionist mandate of the latter has served as a cover to the UN PKO, which even with a “robust” mandate is uncomfortable with direct confrontation.

Lobbying by France led the EU to also engage with the efforts to stabilize Mali. The EU has established a training mission that supports the work of both MINUMSA and the French-led “Operation Barkhane”. Notably, the latter receives significant funding from the EU.

Although both the AU and ECOWAS gave their backing to MINUSMA and “Operation Barkhane”, they are critical of the fact that they have been effectively squeezed out of these PKOs, which are now run by the UN and European actors. This arrangement, on the one hand, ensures that PKOs in Mali are better financed and resourced. Yet, on the other hand, this is not compatible with efforts to increase the role of regional and local voices in PKOs. Indeed, the UN would seem to have sided with the French-led PKO over the African-led one, by granting the former its endorsement after already authorizing the latter, and moving to replace the latter before its mandate had expired.

In Somalia, the long-term sustainability of the AU-led PKO is dependent on the EU’s priorities for its external funding. In Mali, there is significant funding available from the UN, with additional missions funded by the EU and France, but the long-term sustainability of the PKO is questionable. African ROs only have minor roles and little political investment in the process. Should the political will of the UN, EU or France to lead PKOs in Mali decline, as is perfectly possible due to MINUSMA being the deadliest PKO for peacekeepers in UN history, there is no African-led PKO readily in place to step in and fill a potential security void. As the AU or ECOWAS have had little input into the mandate of the existing operation, a smooth transition between a UN-led and an African-led PKO would be unlikely.

The Way Forward

The UN’s efforts to work more closely with ROs is an important development for meeting the demand for peacekeeping in Africa and worldwide. There are numerous advantages, including reducing the resource and political risk burden on the UN, and enhancing the regional legitimacy of UN PKOs. However, these arrangements often do little to overcome a shortfall in finance and expertise to support PKOs.

In Africa, this has led to the EU becoming a regular third institutional player in peacekeeping cooperation between the UN and AU, mainly as a donor and supplier of expert training. Therefore, the ongoing efforts to further the UN-AU relationship should also encompass a focus on UN-AU-EU trilateral relations. A third UN-AU-EU trilateral meeting was held in September 2018. However, this trilateral dialogue should be extended beyond a summit, to include the creation of specific trilateral coordination mechanisms for each PKO in which all three organizations play a role. This is imperative for establishing a clearer understanding of how they can work together, and manage some of the contested political issues and operational shortcomings that have emerged in their inter-organizational peacekeeping collaborations to date.

As the case of AMISOM highlights, the UN and AU need to continue to work towards a common understanding about each other’s differing interpretations of “robust” peacekeeping. While the latter is more prepared to practice “peace enforcement”, the former insists “robust” does not amount to “enforcement”. As long as these distinct visions of peacekeeping are maintained, then it will be politically difficult for one to hand over a PKO to the other.

Furthermore, the vague and informal nature of the division of labour, responsibilities and commitments between the three organizations represents an important challenge to the sustainability of the PKOs. There is a danger that if one partner changes their position (withdraws, or shifts its priorities), then the whole arrangement will collapse or become hamstrung by operational obstacles. It is, therefore, important for these organizations to establish more clearly demarcated arrangements with one another, including the definition of their long-term commitment to the PKO. This would create better conditions for effective inter-organizational peacekeeping collaboration.

About the Authors

Stephen Aris is a senior researcher at the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich, focusing on the study of regionalism and international institutions.

Kirsten König is a research assistant at the CSS and teaching assistant at the University of Zurich.

This CSS Analysis draws on work from a larger SNF-funded project “Which region? The politics of the UN Security Council P5 in international security crises”.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.