Violence and Non-Violence in Anti-Government Mobilization

21 Nov 2016

By David E Cunningham, Belén González, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, Dragana Vidović and Peter B White for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pagePeace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)call_made in November 2016.

Grievances against a government can motivate a wide range of forms of popular mass mobilization, yet violent events have received disproportionate attention. Existing data indicate that non-violent challenges to the government have been more common than violent challenges, whereas violence has been relatively more likely for territorial disputes. The choice of tactics is closely related to objectives and mobilization potential, and many actors seeking to challenge the government are likely to be more effective using non-violence than violence. Although grievances may be ubiquitous in autocratic regimes, active claims are not, and we show how our new data allow us to study separately claims against the government and factors affecting mobilization.

Brief Points

- Despite the widespread focus on violent events, non-violent anti-government mass mobilization has been more common than violent challenges

- Non-violence is more likely to be used and is more effective than violent mobilization when actors can mobilize much larger numbers

- Most cases where individuals have plausible grievances against autocratic governments do not see large-scale mobilization

- Separating anti-government claims from mass mobilization provides new insights into initial motives and opportunities for mobilization

Anti-Government Mobilization

Conflict research and media attention to anti-government mobilization is often skewed towards violent events, such as the current civil war in Syria. General definitions of conflict, however, emphasize the underlying incompatibilities or conflict of interests between actors rather than the specific means that actors use. Although grievances against the government can motivate violence, they can also and often do motivate other responses, including forms of non-violent direct action such as protests, strikes, and boycotts. During the Arab Spring, for example, long-standing dictators in Tunisia and Egypt were ousted through large-scale non-violent mobilization. Despite the common focus on violence, large-scale non-violent challenges to the government have been more common than violent challenges, and non-violent mobilization has often posed more severe challenges to authoritarian governments than violent campaigns.

In this policy brief, we describe what our research tells us about grievances over the government, when actors chose non-violent means to contest the government, and how this compares to the use of violence. We draw on insights from a new data set documenting claims made by dissident organizations against the government that allows for examining when we are more likely to see either violent or non-violent mobilization over these claims.

Grievances and Active Dissent against the Government

Many researchers argue that conflict over different incompatibilities tends to be driven by distinct factors and processes. For example, ethnic groups are more likely to seek independence or greater autonomy, and the risk of violence in such disputes increases when groups face greater political exclusion and marginalization and have a higher ability to challenge the government militarily (e.g., Buhaug, 2006; Cederman et al., 2013, Cunningham, 2013). However, there has been much less attention to conflicts over the central government – including claims over the political system, leader or government selection – and the specific means of mobilization that actors choose.

We argue that the key underlying motives are conceptually similar across violent and nonviolent large-scale popular mobilization against the government. Both arise under political and economic exclusion in autocratic systems, where acts of dissent inherently involve a challenge to government authority and must rely on direct action as conventional forms of politics are closed off and opposition is not tolerated. In democracies, actors have a wide range of opportunities to influence governments and policies through legal avenues and competitive elections. Indeed, the only clear case of new violent mobilization against the central government emerging in a democracy is the 1971 Marxist JVP rebellion in Sri Lanka, although some democracies see violent separatist movements by ethnic groups that reject the existing nation-state. Moreover, non-violent direct action challenging the government itself is also rare outside autocracies, and generally restricted to cases where the degree of democracy is questionable, such as the 2004 Orange Revolution in Ukraine, following contested elections widely seen as stolen.

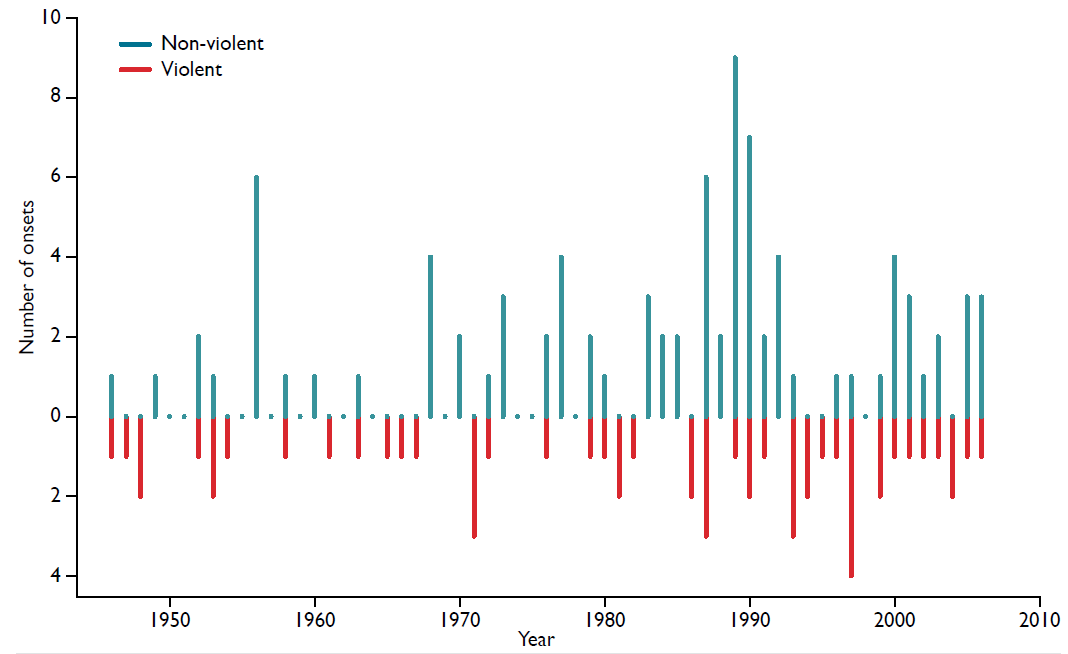

State capacity is often defined by control of the means of violence, and there is a common folk wisdom that violent uprisings are the most serious threats to the government. However, our research actually shows that large-scale non-violent challenges to the government have been more common than violent challenges and often have a bigger impact (see Dahl et al., 2016; Gleditsch et al., 2016). Figure 1 compares the number of non-violent outbreaks of mass mobilization against the government to violent challenges and shows that the former have been more common. By contrast, violence has been more common than non-violence in mobilization for claims over territory, typically involving distinct ethnic groups. Moreover, non-violent mobilization has more often preceded concessions or reforms than violent challenges. Gleditsch et al. (2016) shows leaders have lost office twice as often under non-violent than violent challenges (see also Chenoweth & Stephan, 2011).

Mobilizing large-scale dissent is difficult in a dictatorship, and the government typically uses repression to deter or suppress dissent. Given the high risk to participants, it is not surprising that large-scale mobilization against the government remains rare, even if grievances are widespread. However, comparing cases where we see active dissent reveals important clear differences between non-violent and violent challenges.

Whereas violent challenges to the government can evade repression by going underground, non-violent challenges inherently rely on public opposition. Since individual participants must expose themselves to the government, it is a risky proposition without sufficiently high total participation and efforts to mobilize will be unlikely to impose significant costs on the government unless participation is high. Hence, mobilizations will often fail to materialize when participation cannot be expected to be sufficiently large, even if grievances against the government are widely held.

With high participation, however, large-scale non-violent dissent and refusal to comply with state authority can impose substantial costs on the government and increase the likelihood of elite defections. The risks to individual participants from repression decline rapidly with larger total numbers. It is easier to attract more participants for non-violent campaigns as no particular skills are required, and dissent does not require leaving civilian life behind to the same extent as joining a rebel group. By contrast, the feasible participation in violent dissent is normally capped at a low level, at least in the short run, since converting sympathizers into capable rebels requires arms and training.

It is generally more difficult for the government to repress large numbers in non-violent protest, and doing so leads to higher risks of international condemnation. If violence alienates some potential participants, then maximum participation under violence declines even further relative to non-violence. Thus, even under a conservative and questionable assumption that non-violent dissent is never absolutely more effective than violent dissent with the same number of active participants, non-violent dissent can still be relatively more effective than violence if a sufficiently larger number of active participants can be mobilized. Thus, dissidents with broad appeal and the ability to mobilize more participants should be more likely to use non-violent tactics, while the resort to violence often arises as an adaptation to low mobilization capacity. We show elsewhere that data on participants and proxies for resources in different types of mass mobilizations are consistent with these expectations (Dahl et al., 2016; White et al, 2015).

From Claims to Mobilization

The path from grievances over the government to manifest claims is complex, and incipient mobilizations can fail at many stages. Our research separates the process leading to large-scale mobilization into stages to understand why some countries see smaller-scale anti-regime activity while others experience large-scale mobilization though either violent or non-violent tactics, and while yet others see no anti-regime activity at all. Claims against governments and mobilization are led by organizations willing to engage in anti-regime action. We can think of organizational expression of anti-regime grievances as a precondition for large-scale mobilization, whether non-violent or violent. We have collected annual data on expression of grievances by organized dissidents for nearly 100 randomly selected countries, not including consolidated democracies. We identify these through named dissident organizations or other social organizations (e.g., unions, students, religious congregations) making public statements calling for a fundamental change to the political system (e.g., establishing democracy in a dictatorship), the composition of the central government, or the electoral process (e.g., claims of electoral fraud). Our data on governmental incompatibilities identify conflicts over government independent of mobilization, where we can examine what drives these disputes to evolve into violent or non-violent mobilization, or no large-scale dissent.

Contrary to the common claim that grievances are ubiquitous and cannot explain political action, we show that organizations expressing anti-regime grievances are not ubiquitous. We find active claims in only about 50% of the possible cases with plausible grievances, indicating that a significant share either lack sufficient grievances to result in public claims, or that the costs to publically challenge the government are so high that potential dissidents either fail to organize or choose not to do so.

Most governmental incompatibilities do not lead to either violent or non-violent mass mobilization. In our data, civil war takes place about 20% of the time when organizations are expressing anti-regime grievances, while non-violent campaigns occur about 6% of the time. However, even though violent civil wars are more frequent in terms of incidence than large-scale non-violent campaigns, this primarily reflects how civil wars tend to last much longer than non-violent campaigns, which tend to either succeed or fail relatively quickly, while some violent insurgencies have lasted for decades. When we look at new outbreaks we actually see more non-violent campaigns breaking out than new outbreaks of civil wars, especially after 2000. In our data, we find about twice as many non-violent campaign onsets over the government as civil war onsets over governmental incompatibilities. Moreover, while existing data show that civil wars appear to have become less common and generally less severe since the end of the Cold War, non-violent mass mobilization has become relatively more common.

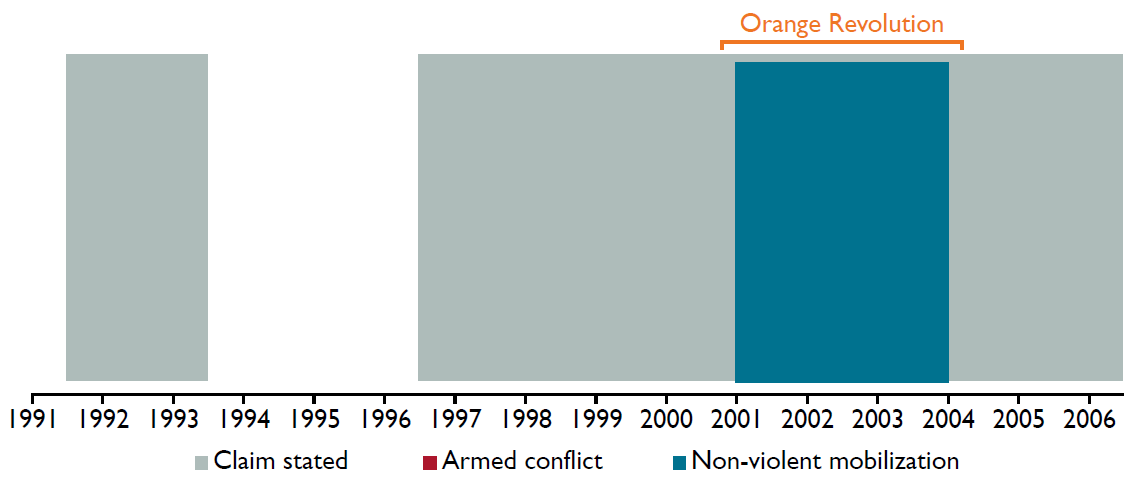

We use Ukraine as an example to illustrate our new data on claims and their use in studying mobilization. Unlike for example the Baltic republics, where the transition to competitive democratic systems was generally swift, Ukraine has suffered from high levels of corruption, generally poor governance, and several efforts to subvert the electoral process after independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. This has given rise to a large number of organizations articulating incompatibilities over the government. In our data, we see a high frequency of maximalist claims on the government, as displayed in the timeline of claims and instances of mass mobilization in Figure 2 over the period 1991–2006 (the end of the current NAVCO data). As can be seen, claims predate the well-known 2004 Orange revolution.

Mass mobilization against the government in Ukraine has been largely non-violent, with mass protest located in the capital Kiev and urban centers. Non-violent challenges to the government have been facilitated by a mix of clear motives and facilitating factors. By contrast, the violent conflict in the East of Ukraine following the ousting of Yanukovych in 2014 is a separatist conflict, emanating from the East-West split on closer ties with Russia, although the turn to active violence could be seen as a response to the changes following the Maidan protest. The general use of non-violent tactics in challenges to the government and calls for political reform is consistent with our claims above on the characteristics that support mobilizing large numbers of dissidents. Ukraine is a largely urban country, with more than two-thirds living in cities at independence. Although there has been substantial government pressure in Ukraine on media outlets over the period, the press has often broken free of restrictions and helped disseminate awareness of grievances and mobilize dissent. The 2004 Orange Revolution was preceded by a “Journalists Rebellion”, where a prominent newscaster accused the government of electoral fraud. The main Ukrainian dissident group Pora! (It’s Time!) also benefitted from the prior success of Otpor! (Resistance!) in non-violent mobilization to overthrow Milosevic in Serbia, as well as support and training from pro-democracy activists and international actors. By contrast, the narrow base of the eastern separatist movement and relative lack of influence in the capital are much less favorable for effective non-violence, and Russian military support further promotes violent tactics.

Predicting Future Mobilization

Separating out the initial stage in which organizations express anti-regime grievances and the latter stage of large-scale mobilization can enhance our understanding of when and where these conflicts take place, as well as potentially how to prevent them and promote non-violent tactics. While active civil wars fortunately are relatively uncommon, many societies have a potential for large-scale unrest. By identifying governmental incompatibilities – potential violent or non-violent conflicts over government – we can track the development of organizations and their resource base to update the assessment of the likelihood of future challenges.

Identifying a set of countries with the potential to experience civil war and non-violent campaigns can guide policymakers as to where to focus their attention if they are interested in preventing disputes from becoming violent or to try to foster knowledge about the opportunities for non-violent action for political change.

Additionally, thinking about dissidents and governments as strategic actors who choose whether and how to engage the state and respond to challenges can help to guide how to intervene in these disputes. Many dissidents may be open to using non-violent tactics as opposed to violence, but may not see them as potentially effective, or see violence as justified against an oppressive government. External actors can influence this choice by trying to discourage governments from responding to protest with violent repression and by working to promote international awareness or support for non-violent action.

References

Buhaug, Halvard (2006) ‘Relative capability and rebel objective in civil war’, Journal of Peace Research 43(6): 691–708.

Cederman, Lars-Erik, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch & Halvard Buhaug (2013) Grievances, Inequality, and Civil War. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Chenoweth, Erica, & Orion A Lewis (2013) ‘Un- packing nonviolent campaigns: Introducing the NAVCO 2.0 dataset’, Journal of Peace Research 50(4): 415–23.

Chenoweth, Erica & Maria J. Stephan (2011) Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Non-violent Conflict. New York: Columbia University Press.

Cunningham, Kathleen G. (2013) ‘Understanding strategic choice: The determinants of civil war and nonviolent campaign in self-determination disputes’, Journal of Peace Research 50(3): 291–304.

Dahl, Marianne, Scott Gates, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch & Belén González (2016) ‘Accounting for numbers: How group characteristics shape the choice of violent and non-violent tactics’, Type-script, Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede, Roman Olar & Marius Radean (2016) ‘Going, going, gone: Varieties of dissent and leader exit’, Typescript, Peace Research Institute Oslo.

Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg & Håvard Strand (2002) ‘Armed conflict 1946–2001: A new dataset’, Journal of Peace Research 39(5): 615–37.

White, Peter B., Dragana Vidović, Belén

González, Kristian Skrede Gleditsch & David E. Cunningham (2015) ‘Nonviolence as a weapon of the resourceful: From claims to tactics in mobilization’, Mobilization: An International Quarterly 20(4): 471–491.

About the Authors

David Cunningham is Professor and Peter White is a PhD candidate at the University of Maryland. Belén González is a Research Fellow at the University of Mannheim. Kristian Skrede Gleditsch is Professor and Dragana Vidović is a PhD candidate at the University of Essex. Cunningham, González, and Gleditsch are also research associates at PRIO.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.