The Effects of Ceasefires in Colombian Peace Processes

24 Sep 2018

By Reidun Ryland, Tora Sagård, Peder Landsverk, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, Siri Aas Rustad, Håvard Strand, Govinda Clayton, Claudia Wiehler and Valerie Sticher for Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by external pagePeace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO)call_made in September 2018. external pageImagecall_made courtesy of Flavia Carpio/Unsplash.

Ceasefires play a crucial role in efforts to build and sustain peace. Despite the importance of ceasefires, they have received little scholarly attention. We examine the occurrence and effect of ceasefires in the armed conflict in Colombia. Our findings indicate that ceasefires played a facilitating role in reducing the number of fatalities in the conflict between FARC and the government during the most recent peace process. We do not find the same trend for earlier peace processes. As for the most recent peace efforts with ELN, at present, there is no available data on the number of fatalities.

Brief Points

- Since 1989 there have been 27 ceasefires in Colombia, of which 21 were declared unilaterally

- The on-going process between ELN and the government is the only peace process in Colombia that started with a bilateral ceasefire agreement

- Ceasefires do not automatically lead to fewer battle deaths

- The nature and dynamics of the conflict, as well as aspects of the group, shape the effects of ceasefires

Ceasefires in Colombia

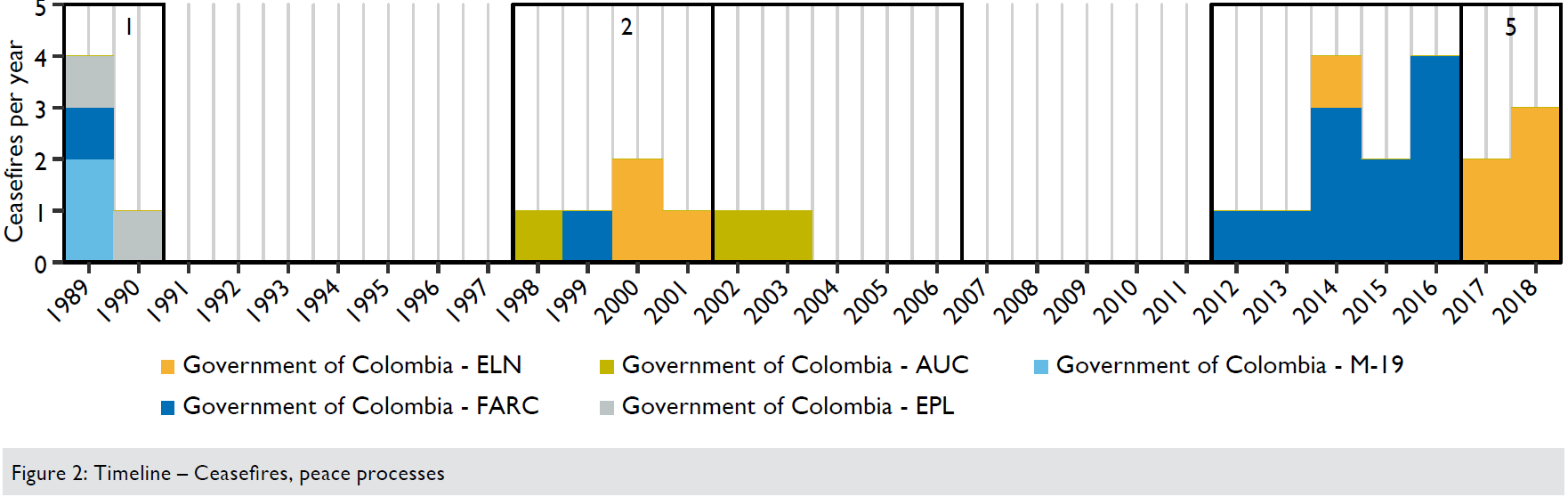

Since 1989, 27 ceasefires have been declared in Colombia, involving: the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC); The National Liberation Army (ELN); the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC); M-19; and the Popular Liberation Army (EPL).

FARC is the most frequent participant, with 13 ceasefires, followed by ELN (8), AUC (3), M-19 (2) and EPL (2). The Government of Colombia has participated in six ceasefires.

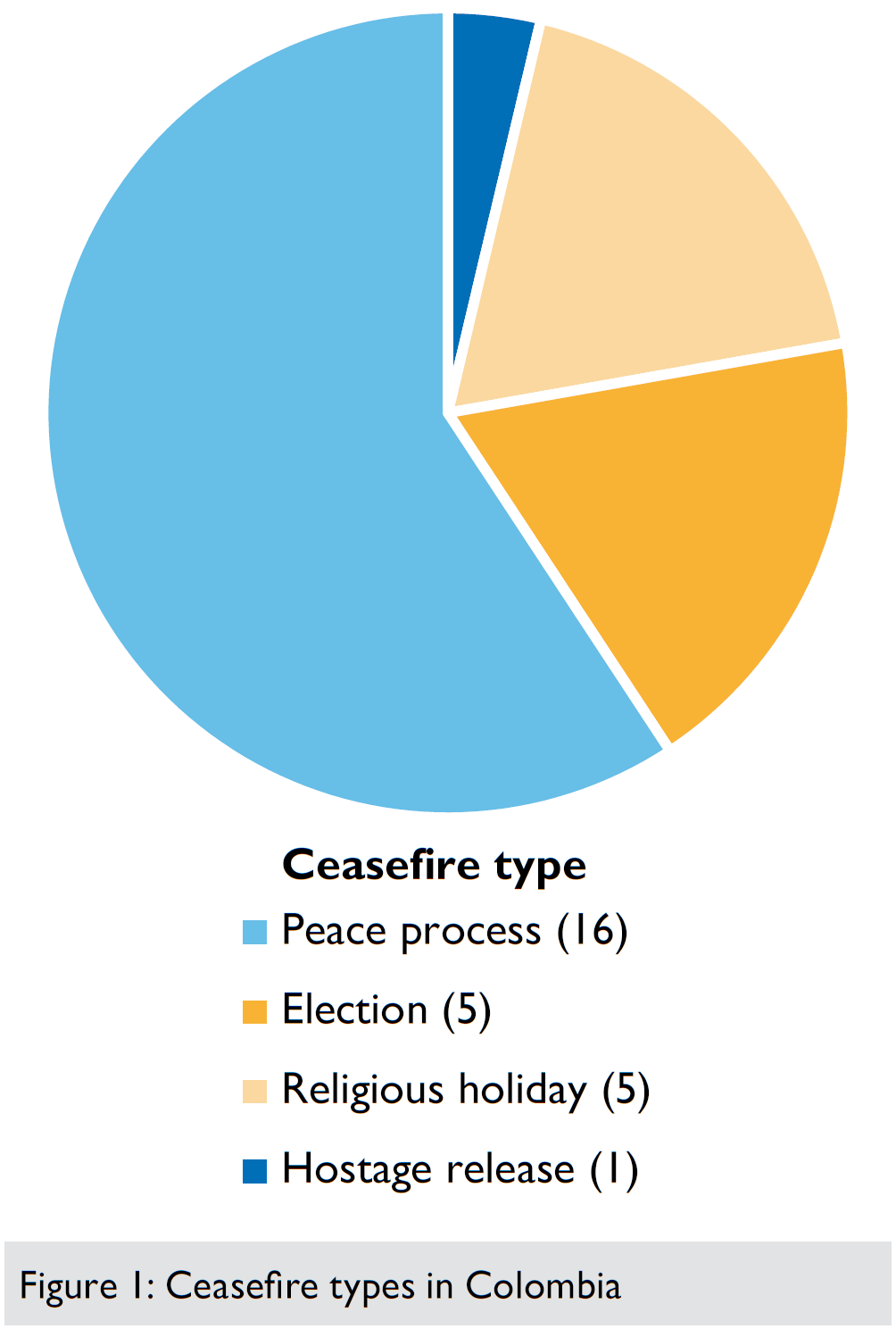

An important distinction is between bilateral and unilateral ceasefires. In the dataset, a bilateral ceasefire is a mutual agreement between two or more actors. A unilateral ceasefire is if the cessation of hostilities is undertaken by only one group alone.

A majority (21) of the ceasefires in Colombia were declared unilaterally by an insurgent group. This is also the case for the ceasefires declared during or as part of an on-going peace process between the government and a group. The declaration of unilateral ceasefires is routinely used by rebel groups as a mechanism by which to establish good-will, or to reaffirm or start an ongoing peace process, either by own choice, or by the government’s urging.

As many as 11 ceasefires were declared unilaterally by one of the warring parties in an effort to help or salvage a peace process. In July 2015, for instance, the FARC announced a unilateral truce in attempt to rescue failing peace talks. Warring parties can use unilateral ceasefires to show the government that they are dedicated to the peace process. Indeed, the truce declared by FARC in 2015 made it possible for the parties to formally sign a peace agreement a year later. The remaining 10 unilateral ceasefires have primarily been related to religious holidays or elections.

We have recorded six bilateral ceasefire agreements, of which five are related to a peace process. Note that these five ceasefires all came into effect after 2016, and four of them were extensions of the same ceasefire. Bilateral ceasefire agreements, which require the consent of both parties, are naturally harder to reach than unilateral ones. Consequently, bilateral ceasefires are generally seen in the later stages of a peace process – often a sign of a more mature process.

Ceasefires and Colombian Peace Processes

The ceasefires in Colombia have clustered around three periods, shown in Figure 2. These three clusters broadly overlap with five peace processes between, on the one hand, the government, and on the other hand, ELN, AUC, M-19, EPL, and FARC. However, this does not imply that all ceasefires were initiated as part of the peace process or, for that matter, with the purpose of promoting peace talks. It is worth noting that no ceasefires have been declared in Colombia outside of an on-going peace process. This is in contrast to other conflicts where we routinely see truces outside of formal peace processes.

The first cluster of ceasefires are found in the 1989 to 1991 period. In this period, there were attempts at peace negotiations between the government and FARC, ELN, M-19, EPL as well as some smaller insurgent groups. The first four ceasefires in this period paved the way for the successful demobilization of M-19 (1989) and EPL (1991). The final ceasefire was part of a failed attempt by FARC to initiate direct talks with the government. All ceasefires were unilaterally declared by insurgents.

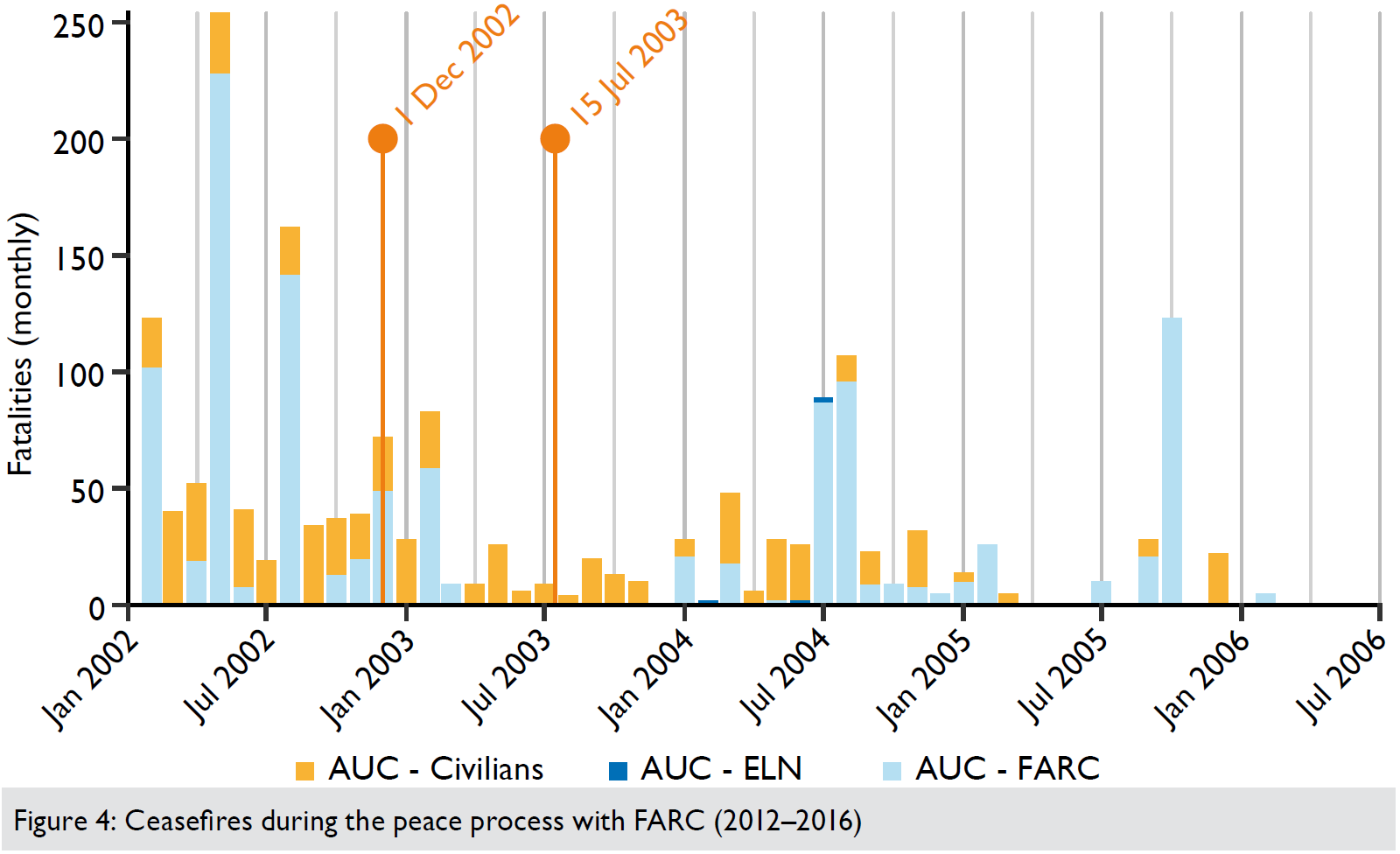

The second period spans roughly from 1998 to 2002. Here, the government had separate talks with FARC and ELN. Four out of five ceasefires in this period were declared by these two insurgent groups. Nevertheless, none of them were directly related to the peace process. Instead, three were related to religious holidays, while the fourth was connected to the release of hostages. The latter was also the only bilateral ceasefire. The negotiations between FARC and ELN broke down when Álvaro Uribe took office as President of Colombia in 2002. This was the same year that negotiations were initiated with the AUC, who declared a unilateral truce as part of preconditions to start talks. This ceasefire was later extended in the demobilization pacts of 2003 and 2004, ending with the completion of disarmament of AUC in 2006.

Peace Processes under the Santos Administration

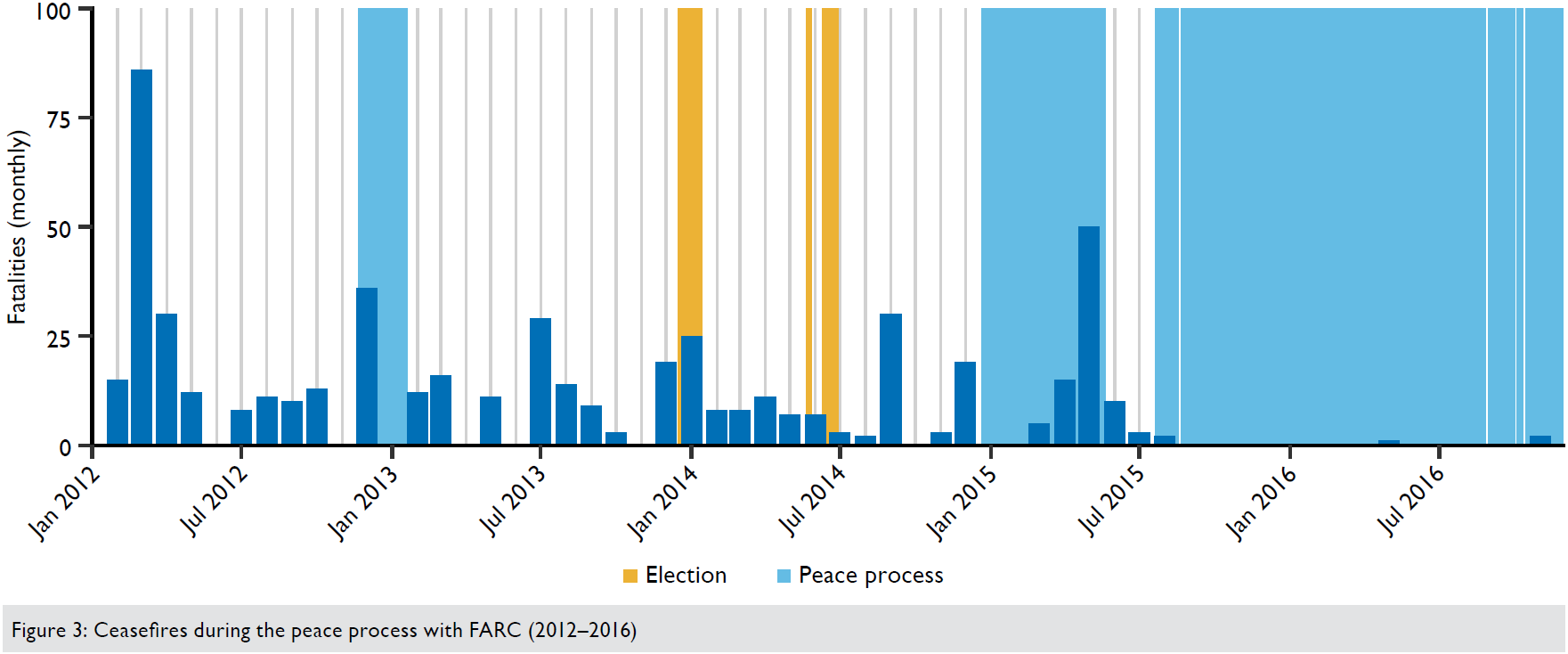

Negotiations between the government and FARC re-started officially in 2012. Since then, there have been 11 ceasefires, where three of them were not directly linked to the negotiations (Figure 3).

Most of the ceasefires declared in this period were unilateral. In fact, no bilateral ceasefire was declared until August 2016. There is some indication that the government resisted bilateral ceasefires for fear that FARC would use it as an opportunity to rearm. Nonetheless, the government did reduce its military activities in response to some of FARC’s unilateral ceasefires. Only days after FARC declared a unilateral ceasefire in July 2015, for instance, the government announced it would halt some military activities.

With the completion of the peace agreement, the government and FARC declared a “definitive bilateral ceasefire and cessation of hostilities” on August 29, 2016. The ceasefires that followed were reiterations of the same agreement: first, after the referendum, then they were further extended twice in mid- October, and in the end they were replaced by the final agreement.

The fifth and so far final peace process started between the ELN and the government in February 2017, after several failed attempts. Six months into negotiations, a temporary bilateral ceasefire was announced. The truce ended after the fixed period lapsed in January 2018. The two parties have not yet managed to negotiate a new agreement, marking this ceasefire as the only bilateral agreement related to a peace process that the government has not managed to prolong. The ELN have declared three unilateral election-time truces since then.

The peace process with the ELN differs from the other peace processes in that the ELN has not declared any unilateral ceasefires related to peace negotiations. Under the other peace processes, the government required that insurgents show commitment to the process through such unilateral ceasefires. In the case of the ELN, however, the government agreed to a temporary bilateral agreement early on in the talks. One possible explanation for this is that since the Santos administration had already concluded a successful peace process with FARC, it felt confident, going into the negotiations with ELN, that they could reach an agreement.

The new government has reiterated its conditions for furthering peace negotiations with the ELN, after a one-month evaluation of the previous negotiations. The conditions are for the ELN to release all hostages and cease all criminal activity. As part of the condition to cease criminal activities, there is a demand for the ELN to declare a unilateral ceasefire. If that were to happen, we might see a return to the pattern of negotiations coupled by several unilateral ceasefires. However, the ELN has announced that the conditions are unacceptable. Thus, negotiations are currently gridlocked.

Do Ceasefires Lead to Less Killing?

A successful ceasefire should lead to a deescalation of the conflict and reduced killing. This, however, is not always the case.

Figure 3 shows a sudden and sustained drop in fatalities in the conflict in July 2015. This drop comes as a consequence of the peace process, and in particular the ceasefires, between FARC and the government. This pattern is consistent with the scholarly literature that has emphasized that ceasefires are often initiated in the early phases of peace processes in order to reach a cessation of hostilities and establish momentum for further talks.

In contrast, the peace process between the government and AUC exhibits a different pattern. As illustrated in Figure 4, even though the ceasefire declared in December 2002 was reiterated and in-force throughout the demobilization process, fatalities directly related to this particular conflict did not subside. In fact, killings either perpetrated by or inflicted on the AUC ended only with the conclusion of disarmament in 2006. For the peace process with the FARC, in contrast, fatalities ended over a year before disarmament and demobilization was concluded.

One possible explanation for these discrepancies are the differences between the groups. The AUC is an umbrella organization consisting of several small groups. The group leadership might therefore have less control over all of its members. There is anecdotal evidence supporting this: during the first 21 months of the ceasefire, over 300 people were killed mainly by two AUC factions. Broader group-level organizational aspects of this kind and their impact on the effectiveness of ceasefires are woefully under-researched.

Another possible explanation lies in the different natures of the conflicts. The AUC was formed with the main purpose of defeating left-wing guerilla movements and promoting right-wing politics. There was no direct conflict with the state, and there are therefore no registered fatalities due to fighting between AUC and the government. For FARC however, most fatalities inflicted by or against them have come as part of the conflict with the government.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Research has paid only limited attention to ceasefire agreements. We still know little about when and why they come into force and when they are effective. Nonetheless, ceasefires are clearly related to the level of fatalities in conflict and deserve far more attention.To that end, this project has conducted a first pilot study of ceasefires in Colombia. This is the first step in a more comprehensive data collection project on ceasefires which is currently on-going as a collaboration between PRIO and the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zurich. The dataset will contain all ceasefires in the internal armed conflicts in the 1989–2017 period.

When ready, this data will allow us to explore a range of issues relating to when and why armed actors declare ceasefires. The data will also be used to explore how ceasefires affect the dynamics of conflict and peace processes.

However, the data only focuses on ceasefires in conflict in which the government is an active part. This means that ceasefires between nonstate actors are at the moment not included. In the Colombian case, this entails that we are missing potentially crucial information on ceasefires in conflicts between, for instance, AUC and the FARC. Mapping such non-state ceasefires is an important avenue for future mapping exercises.

For present-day Colombia, a key question is how the most recent ceasefires in the conflict with the ELN will affect the intensity and the number of fatalities seen in that conflict. We lack the data necessary to examine that question. Nonetheless, ELN, like FARC, is a unified, left-wing guerilla, which has primarily been engaged in a direct confrontation with the state. If history is any guide, we can be cautious optimists and expect a similar relationship between ceasefires and fatalities to that observed for the conflict with the FARC. That is given a continuation of the peace process under the new administration.

About the Authors

Reidun Ryland and Tora Sagård are Research Assistants; Peder Landsverk is a Master’s Student; and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård and Siri Aas Rustad are Senior Researchers at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

Håvard Strand is Associate Professor at the University of Oslo (UiO) and Senior Researcher at PRIO.

Govinda Clayton is Senior Researcher, Claudia Wiehler is Research Assistant, and Valerie Sticher is a senior program officer at the Center for Security Studies at ETH Zürich.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.