The Future of NATO and R2P: Ten Lessons in Norm Formation

20 Mar 2017

By Brooke Smith-Windsor for NATO Defense College (NDC)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageNATO Defense College (NDC)call_made in March 2017.

NATO, Libya and the Responsibility to Protect

To this day, a visit to NATO’s official website paints a glowing account of its 2011 military intervention in Libya under United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1973:

Following the Gaddafi regime’s targeting of civilians in February 2011, NATO answered the United Nation’s (UN) call to the international community to protect the Libyan people … a coalition of NATO Allies and partners began enforcing an arms embargo, maintaining a no-fly zone and protecting civilians and civilian populated areas from attack or the threat of attack under Operation Unified Protector (OUP). OUP successfully concluded on 31 October 2011.

While immediate operational goals may have been achieved, and urgent threats to lives in Benghazi and elsewhere averted, more than half a decade hence the post-intervention legacy is far from rosy. What followed the collapse of the Gaddafi regime in October 2011 is a Libya and neighbourhood still rife with instability and violence facing the spectre of widespread civil strife and even collapse. Yet one would be at pains to find any acknowledgement of this state of affairs in official Alliance communications beyond tacit recognition by way of oft-repeated, open-ended offers of capacity building assistance. Any exploration of potential causal linkages with the 2011 military campaign is decidedly non-existent. Public pronouncements doing just that nevertheless have begun to emerge in individual member states. Describing Libya in 2016, for example, the UK House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee report on Britain’s contribution to the NATO intervention there candidly remarks:

The United Nations ranked Libya as the world’s 94th most advanced country in its 2015 index on human development, a decline from 53rd place in 2010 … In April 2016, United States President Barack Obama described post-intervention Libya as a ‘shit show.’

The US Congressional Research Service, in the same year assessing future American policy options, catalogues the myriad challenges facing the country ranging from: political discord; the prospect of fiscal collapse; terrorism including the rise of Islamic State and other armed extremist groups; as well as uncontrolled migration and trafficking.

The lack of similar public acknowledgement of the negative outcomes of post-intervention Libya within NATO itself is all the more surprising considering OUP’s positioning at the time, and since, as a test bed—indeed milestone—for the emergent international norm of Responsibility to Protect (R2P) against the threat of mass atrocity crimes; a norm to which all 28 Allies ascribe since its agreement at the World Summit Outcome of 2005 (see below). As Alex Bellamy remarks:

Never in history, prior to Resolution 1973, had the [UN Security] Council authorized the use of force to protect populations without the consent of the de jure authorities. Although such an authorization is not likely to be repeated often, this resolution marked a significant advance in signalling that the Council was no longer unwilling as a matter of principle to take such action, should it be judged necessary.

Yet here too the outcomes were not unreservedly positive. While R2P has since gained unprecedented traction in policy debates of the UN Security Council, some “geopolitical discomfort” with the outcomes, whether intended or not and particularly as regards the resultant regime change, has arisen. As Gareth Evans, the former Australian foreign minister and one of R2P’s principal architects has observed: “we have to frankly recognize that there has been some infection of the whole R2P concept by the perception, accurate or otherwise, that the civilian protection mandate granted by the Council, with no dissenting voices, was manifestly exceeded by that [NATO] military operation.”

The imperative of an R2P debate

As Evans’ observation alludes to, it is with respect to the so-called third pillar of the R2P framework and by extension NATO’s role in its implementation that remains the most controversial. The Australian Red Cross similarly remarks:

The third pillar, and the most contentious, is that if a State is ‘manifestly failing to protect’ its population from the R2P crimes of genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, then the international community is ‘prepared to take collective action in a timely and decisive manner.’ This pillar allows for the possibility of the use of force for protection purposes under Chapter VII of the UN Charter.

Despite the controversy, there remains a distinct possibility that the Atlantic Alliance might once more be called upon to implement the third pillar in accordance with its crisis management vocation (one of its “core tasks” recently reaffirmed at the July 2016 NATO Summit). If there were any doubt about R2P’s ongoing relevance to the Alliance’s crisis management mission, it is useful to recall the historic gravity of mass atrocity crimes, a repetition of which the R2P framework was in 2005 deliberately set up to avert: as the genocide historian Daniel Goldhagen reminds us, in the last hundred years the killing of over 100 million people, more than all combat deaths in all wars during the same period. No surprise, therefore, that the recently retired UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon would in his July 2016 parting report on R2P recall that:

Given the failures of collective action represented by the genocides in Rwanda and Srebrenica, [the Heads of State and Government] aspired to close the gap between existing legal obligations of States, which are clearly laid out in international humanitarian, refugee and human rights law, and the reality of populations threated with large-scale and systematic violence …The security of “We the peoples” matters every bit as much as the security of States.

Closing that gap nevertheless takes time. Only by reflecting on state practice like in the Libya case will the contours of an R2P norm coalesce: “The disagreement regarding R2P and Libya illustrates, that while the norm itself has matured conceptually and politically since the time that human security and humanitarian intervention were first discussed, it is not yet an operational entity. This will require … continual re-evaluation.” This is to be expected and should be welcomed. R2P adds “a fourth characteristic, namely ‘respect for human rights,’ to the three Peace of Westphalia characteristics of a sovereign state—territory, authority and population. Unsurprisingly, this creates tensions … It is this tension that makes analysis of R2P both intellectually interesting and practically necessary.”

Such practical necessity is particularly germane to an organization like NATO which routinely defines its core mission as including a commitment to “shared values such as individual liberty and human rights,” and which prides itself on having the political will and military capacity to defend them. The fact that within NATO official strategic level policy debates on Libya and R2P have been few and far between is, therefore, cause for some concern. The 2014 report commissioned by the Deputy Chief of Staff of the operational command, Joint Force Command Naples, was a useful step forward but more needs to be done. A renewed focus on preparations for collective defense and deterring inter-state conflict in Europe post-Crimea, or rekindled preoccupation with combatting terrorism in anticipation of a Trump administration’s priorities, while significant in their own right, perhaps go some way to explain the lack of recent R2P policy discourse within the Alliance. Or, perchance, it is simply lingering hesitation to confront some uncomfortable truths about the outcomes of the 2011 Libya campaign. Whatever the reasons, as pointed out earlier, if history is any guide, the imperative of preventing mass atrocity crimes will not go away. And, in spite of recent failures to do so in places like Syria, as the International Red Cross also reminds us, “just because interventions cannot be mounted in every case where they should be is no reason for not mounting them in any case.”

In June 2016, Allies mustered the political will necessary to define a “NATO Policy for the Protection of Civilians” during operations, but this is not to be confused with an agreed policy framework for the implementation of R2P. The latter is to be distinguished from International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and relates only to the prevention of the four heinous international crimes described above. Helping to prevent those particular crimes in future by contributing to the debate within the Alliance about R2P norm formation is thus the subject of this paper. This is provided by renewed consideration of the actions of NATO and its members in the context of Operation Unified Protector in Libya.

Learning from legacy outcomes

Such revived reflection essentially means examining OUP’s legacy outcomes or the “lessons identified” from both the “normative” and “operative” perspectives of R2P. For our purposes, a lesson identified is defined as “knowledge from experience that creates value”—in this context, the value of maturing the concept of R2P and the particular contribution of NATO and its member states. The latter formulation is deliberate because, “For the time being, NATO remains an institutional union acting through common organs. Accordingly, each member state bears international responsibility for the acts committed by its forces engaged in NATO operations.” Both institutional and member state memory are, therefore, important here.

The normative perspective of R2P refers to the defined standard or vision of appropriate behavior for state actors as outlined at the 2005 World Summit Outcome in paragraphs 138 and 139. To summarize:

1. Responsibility of a state to protect its populations from mass atrocity crimes (Pillar 1);

2. Responsibility of the international community to assist states to fulfil their responsibility to protect (Pillar 2);

And, once more, particularly significant to NATO and its member states:

3. Preparedness of the international community “to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council, in accordance with the Charter, including Chapter VII, on a case-by-case basis and in cooperation with relevant regional organizations as appropriate, should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities manifestly fail to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity” (Pillar 3).

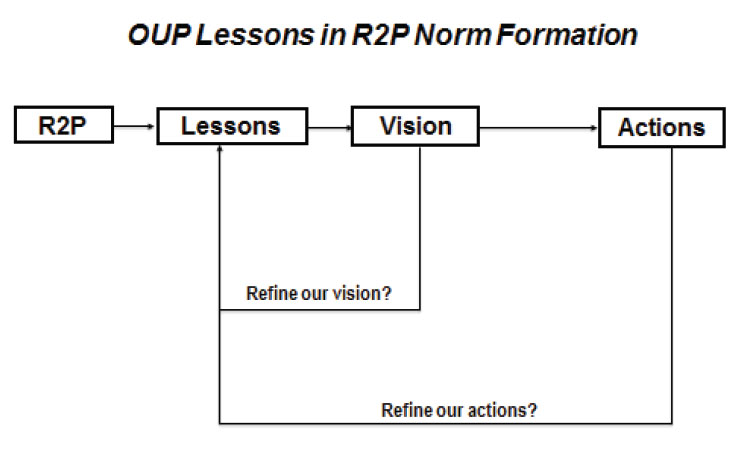

As depicted in Figure 1, the first question for NATO and its member states to explore is: does OUP’s legacy suggest the need for a refinement of the foundational principles that ground the vision of R2P as an emergent international norm? The second question to ask refers to the operative phase: do the actions required to achieve the tenets of that vision need to be refined based on the Libya experience? In answering those two questions from a NATO perspective, this paper will outline 10 lessons: 3 with respect to vision and 7 with respect to actions.

Figure 1

Refine our vision?

1. Values versus interests

The values basis of the original R2P vision is clear and has been previously referred to. The challenge of course is adhering to it because states are also self-interested actors in their international intercourse. In this regard, the UN Secretary General has recently expressed concern that interests have sometimes trumped values and served as a block on R2P: “In some contexts where atrocity crimes have been committed, or are at risk, major powers support opposing factions and put these allegiances ahead of their protection responsibilities.” By the same token, the precursor report that inspired the 2005 World Summit Outcome—Report of the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS)—made reference to “right intention” as one of several criteria to warrant military intervention in the prevention of mass atrocity crimes. The purpose was to avoid states using R2P as a pretext for action serving in the first order their national interest: “The primary purpose of the intervention, whatever other motives intervening states may have, must be to halt or avert human suffering. Right intention is better assured with multilateral operations, clearly supported by regional opinion and the victims concerned.”

When it comes to OUP, values-based calculations for intervention were indeed present. For instance, in America’s case, the “normative arguments, which drew on R2P, were pitted directly against the national interests arguments offered by the Pentagon and others, and succeeded in altering the administration’s approach [to support intervention].” The previously referenced UK House of Commons report likewise refers to lawmakers at the time being influenced by “the horrific examples of Srebrenica, and Rwanda before, which [they] saw unfolding again.”

Nevertheless, it has been reported that narrow national-interest calculations may also have been at play in some quarters summarized as a desire to: gain a greater share in Libya oil production; increase national influence in North Africa; improve the government’s internal political situation; provide the national military with an opportunity to reassert its position in the world; address concerns over Gaddafi’s long-term plans to supplant their national power in Africa.

What is important, however, is for NATO and its member states to affirm—in time for the next humanitarian crisis—that on balance values drove Alliance decision-making. As this author has written elsewhere, states are indeed self-interested when pursuing material benefits. However, the point is that a regular feature of restraint is observed in military policy and action when values and the rule of law principally guide domestic and foreign policy decisions. This was the intent behind the original R2P vision for intervention and is at the foundation of its legitimization of the use of force.

2. Non-sequential pillars

In the immediate aftermath of NATO’s Libya campaign, some governments circumspect of the outcomes endeavoured to offer constructive criticism to improve the vision for R2P. One attempt was made by Brazil in a letter to the UN Secretary-General dated 9 November 2011. To the backdrop of concern that the Atlantic Alliance had resorted to force without first ensuring the depletion of all diplomatic efforts, Brasilia argued that, “The international community must be rigorous in its efforts to exhaust all peaceful means available in the protection of civilians under threat of violence, in line with the principles and purposes of the Charter and as embodied in the 2005 World Summit Outcome.” However, the US delegation among others was quick to question the strict chronological sequence from diplomacy to the use of force implied in the Brazilian note. The reference to “exhausted” was also questioned (recall that the World Summit Outcome uses the phrase: “should peaceful means prove inadequate”).

Appropriate decision-making in this area requires not just ‘temporal’ considerations but a comprehensive assessment of risks and costs and the balance of consequences … We further regret any implication that in those circumstances where collective action is necessary, diplomacy should be considered ‘exhausted’. We should not eliminate the possible role of diplomacy, even—perhaps especially—in situations where forceful action is required.

In other words, timely and decisive action through the use of force does not preclude ongoing diplomatic efforts in tandem. Since the time of the US statement, the UN Secretary General has affirmed this interpretation of the original vision for triggering coercive intervention in the last resort. In his 2009 report on “Implementing the responsibility to protect” he stated:

In a rapidly unfolding emergency situation, the United Nations, regional, sub-regional and national decision makers must remain focused on saving lives through ‘timely and decisive’ action (para. 139 of the Summit Outcome), not on following arbitrary, sequential or graduated policy ladders that prize procedure over substance and process over results.

More recently, in the aforementioned July 2016 report on R2P, the Secretary General reaffirmed this interpretation: “My view has always been that paragraphs 138 and 139 of the World Summit Outcome indicated that the pillars are mutually supporting, and the responsibilities associated with each pillar will often be exercised simultaneously.”

Given these clarifications, NATO and its member states were warranted in resorting to force through UNSCR 1973 if to protect civilians facing perceived grave danger, while not precluding simultaneous diplomatic efforts that to date had failed to secure them. The extent to which new opportunities for diplomacy were considered once the military campaign had been launched, however, is an open question with the benefit of hindsight. The UK Foreign Affairs Committee, for one, has suggested that some national plans had called for a pause in the air campaign once Benghazi had been secured in March 2011, but others did not. This “lack of international coordination to develop an agreed strategy meant that any potential pause for politics became unachievable.” If accurate, Allies would do well to reflect on this episode in time for their next R2P intervention, and insist on a collective understanding of non-sequential pillars to mean still seeking and enabling concurrent diplomatic avenues to conflict resolution even after a military campaign is underway.

3. Recurrence

The ongoing instability and spectre of widespread violence affecting civilian populations in post- Gaddafi Libya has been mentioned previously and is well-documented:

Despite the initial success of the 2011 revolution, the situation in Libya quickly deteriorated as the multiple militias and rebel groups who had fought against Gaddafi rapidly took possession of the massive stockpile of weapons acquired during the dictator’s four-decade reign. The interim government failed to secure control over Gaddafi’s arsenal and, in February 2014, an expert report to the UN Security Council determined that most weapons continued to be controlled by non-State armed groups … The various armed groups also terrorized people and committed human rights abuses. In March 2014 Human Rights Watch warned that government institutions in the country, in particular the judicial system, were at risk of collapse. As a result, the Libyan ambassador to the UN cautioned the Security Council on 27 August, 2014 that Libya is now on the verge of ‘a full-blown civil war.’

The Libya case thus brings to light a scenario where intervention ostensibly to prevent mass atrocity crimes was succeeded by circumstances where their risk of recurrence, albeit by other actors, was also very real. The UN Secretary General has recently raised this issue in discussions about R2P:

Though paragraphs 138 and 139 of the 2005 World Summit Outcome do not explicitly refer to recurrence, the obligation to prevent is a central feature of the responsibility to protect, and prevention and recurrence are closely intertwined … Despite the immense challenges, we know that with the appropriate political will and resources we can prevent the recurrence of atrocity crimes. This has been demonstrated in cases such as Côte d’Ivoire, Timor-Leste, Guinea and Kenya, where the concerted actions of domestic, regional and international actors helped to avert the recurrence of widespread and systematic violence.

A 2014 RAND study, however, observes that in Libya after Gaddafi, “In contrast with all other cases of NATO military intervention, a very small United Nations (UN) mission with no executive authority has led the international effort to stabilize the country. The United States and its NATO allies have played a very limited role.” Yet, as the same report goes on to remark, the Libyan state was not capable of providing security for its population after the war: “Before it could do so, it needed far-reaching security sector reform coupled with disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration of rebel forces. This has proven impossible.”

The reasons for NATO’s lack of engagement in post-2011 Libya have been variously explained as, for example, national electoral cycles and the Afghanistan and Iraq experiences as acting as appetite suppressants in some western capitals for more long-term post-conflict engagements. Whatever the reasons, the costs of inaction over the last half decade have been clear. With respect to the normative vision of R2P, however, the mitigation of a recurrence of atrocities committed against civilians whether real or threated arguably needs to be incorporated into Alliance thinking about protection responsibilities in a post-conflict environment. This, of course, also closely relates to another criterion for R2P intervention first articulated in the aforementioned 2001 ICISS report: “reasonable prospects” whereby the Commission suggests “military intervention is not justified if actual protection cannot be achieved or if the consequences of embarking upon the intervention are likely to be worse than if there is no action at all.”

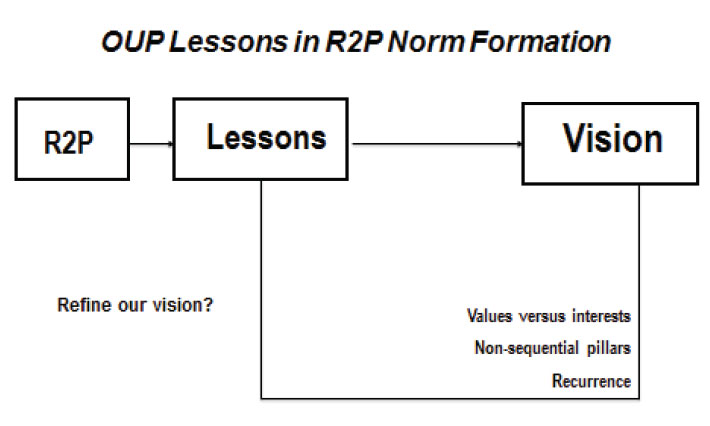

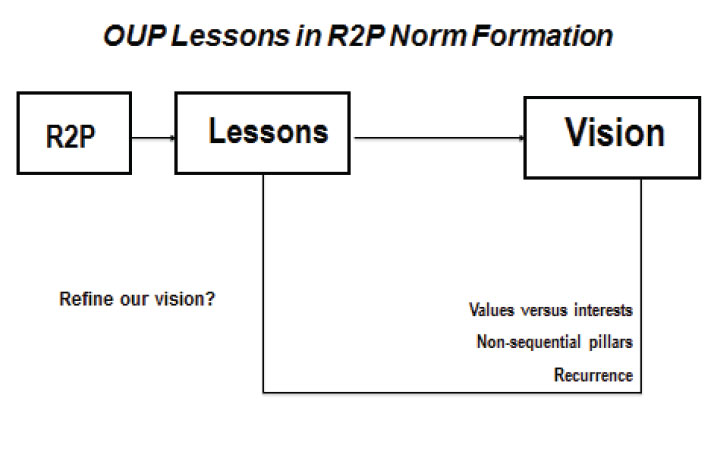

Figure 2 provides a summary of the three lessons from the OUP experience that should serve to help shape thinking within the Alliance and its members about the vision of R2P as a standard of appropriate behaviour by state actors, whether the supported or supporting. The normative foundations of R2P will matter little, however, if they are not backed up with actions to operationalize them. With the benefit of hindsight, OUP can in turn offer a number of lessons with respect to improving actions. 7 are discussed here.

Figure 2

Refine our actions?

4. Validate Indications and Warning

Phase 1 of the NATO Crisis Response System (NCRS) is entitled: “Indications and Warning” (I&W). The idea is to give decision-makers ample time to identify an emergent crisis and to prepare and plan an appropriate response. At its core is to be sound intelligence and information provided by dedicated NATO bodies and the member states.

In the context of R2P, the UN too has emphasized the importance of “early warning and analysis as a foundation for developing rapid, effective and flexible responses to atrocity crimes risks.” In the UN’s case, its Secretary General has highlighted the lack of regard for available information and intelligence in times past: “The internal reports of the Organization’s role in the genocides in Srebrenica and Rwanda pointed to the insufficient attention paid to early warning and to a general institutional weakness in risk analysis.”

As regards Libya in 2011, it has since come to light that it was not so much the lack of attention paid to I&W but to a certain extent least, the quality of information and intelligence on which some NATO member state assessments relied. Attention has focused on allegedly undue credence given to Gaddafi ’s rhetorical threats against civilians. By the same token, a lack of understanding of the regional complexities, actors involved and history giving rise to the rebellion has been profiled. Given these recent observations, those charged with Phase 1 of the NCRS would arguably benefit from deliberating on the OUP episode to discern the extent to which such information and intelligence may have informed the North Atlantic Council’s (NAC) political decision to intervene balanced against the credible reporting. Continual validation of I&W processes is an ongoing requirement and not unique to the Alliance. As the UN Secretary General has stated in referring to R2P:

One of the most pressing needs is greater investment in the human and material resources dedicated to information gathering and analysis, and the generation of viable policy options. This entails increased training of officials at all levels – national, regional and international – on the elements of early warning and early action and efforts to build a supportive environment for their respective work.

5. Advance ‘Responsibility while Protecting’

Whether or not one ascribes to the contention that NATO exceeded its mandate in implementing UNSCR 1973, the affirmative viewpoint expressed by some was real and, as Gareth Evans’ statement quoted at the outset of this paper makes clear, cannot be ignored. Brasilia was particularly vocal in this regard but once more, much of the criticism offered at the time was intended to be constructive. In the same diplomatic note to the UN Secretary General referenced earlier, the concept of Responsibility while Protecting (RwP) was first introduced:

Enhanced Security Council procedures are needed to monitor and assess the manner in which resolutions are interpreted and implemented to ensure responsibility while protecting. The Security Council must ensure the accountability of those to whom authority is granted to resort to force.

This followed the statement made one month prior in the UN General Assembly by then Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff that, “Much is said about the responsibility to protect, yet we hear little about responsibility in protecting. These are concepts that we must develop together.”

While a level of disappointment with Brazil for not maturing the concept is well known, this does not diminish the concept’s value as a means by which to negate fears expressed in the Global South or elsewhere about the possibility of mandate excesses— whether intended or not—by NATO or others in an R2P Pillar 3 contingency. On the occasion of the tenth anniversary of R2P, Evans specifically revived the RwP discussion: ‘

A solution simply has to be found to the current post-Libya stand-off if R2P is to have a future … if we are not, in the face of extreme mass atrocity situations, to go back to the bad old days of indefensible inaction, as with Cambodia, or Rwanda or Bosnia, or of otherwise defensible action taken in defiance of the UN Charter, as in Kosovo.’ [Evans] pinned his hopes for that solution on some variant of the ‘Responsibility while Protecting’ (RwP) idea ...

The reference to Kosovo is important and not simply because the 1999 military operation there (Allied Force) was a NATO one. As a 2015 analysis observes:

The state practice necessary for identifying a customary rule in this area remains unclear and 15 years after Kosovo the situation remains much discussed, but has not yet been ‘settled’. While the opinion juris clearly points to a limited allowance for the use of force when a state has exceeded its scope of ‘sovereignty’ by abusing its population, the matter ‘without UNSC authorization’ is largely untested.

So if the emergence of a customary norm allowing resort to force on humanitarian grounds without Security Council authorization has yet to occur, R2P Pillar 3 remains in 2017 the international community’s—and the Atlantic Alliance’s—principal operative framework for forceful humanitarian intervention to prevent mass atrocities. All the more reason to clarify, post-OUP, the role of the Security Council (3 permanent members of which are NATO Allies) as RwP intended. In this regard, the essence of the debate of which NATO and its members need to be a proactive part, turns on the extent to which “the Security Council leaves to states the operational control and even the strategic direction, but maintains an effective political control over the operations.” The latter concerns “the power to verify through the reporting system the respect for the limits set in the authorization, to assess the objectives achieved, and ultimately to suspend or put an end to the operations.”

6. Acknowledge air power limitations

The lack of NATO involvement in Libya following the conclusion of OUP in October 2011 has already been referred to. One glaring absence was the lack of “boots on the ground” once the air campaign had concluded. UNSCR 1973 forbade their deployment when authorizing the initial international intervention so a new Security Council mandate would have been required. That Allies apparently neither sought one nor planned for such a contingency nevertheless broke with historic precedent:

Prior to Libya, NATO military interventions had normally been followed by post-conflict operations of significant size. In 1995, NATO deployed forces in Bosnia to safeguard the Dayton Accords. Soon thereafter, international actors set up an Office of the High Representative with executive authority to intervene in Bosnian politics to help implement the Accords’ civilian aspects. In Kosovo in 1999, NATO followed up its air campaign with the deployment of peacekeeping forces and the UN set up a large civilian administrative structure to help manage postwar Kosovo’s challenges.

The deterioration of security and stability in post- Gaddafi Libya may in part be explained by the lack of an international peacekeeping ground force whether NATO, UN or otherwise. RAND for one has begun to investigate this correlation suggesting that even a smaller scale deployment with a troops-to- inhabitants ratio of 10:1000 (approximately 61 000 peacekeepers) may have sufficed: “It is reasonable to believe … that even [this] smaller effort, and certainly [a] medium-sized effort, would have been beneficial in creating space for disarmament, demobilization and reintegration, and security sector reform.” As the study equally acknowledges, however, more still needs to be done in estimating ground force requirements for multinational stabilization operations. Given the Alliance’s historic precedents with such deployments and considering the limitations of air power that OUP brought to light, NATO military strategists have good reason to be engaged in this analysis—ideally prior to the next political decision to launch an R2P intervention.

7. Sustain P3 leadership

In advancing R2P, the UN Secretary General has remarked on the importance of the five permanent members of the Security Council exercising leadership given their influence and veto power there. In NATO’s case this refers to the US, France and Britain (P3). OUP was notable given the significant leadership role exercised by the latter two member states in the conduct of the operation albeit considerably enabled by the US in the areas of air-to-air refuelling, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), and strategic lift for instance. As the US Permanent Representative to NATO and the Alliance’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) jointly observed at the time:

Within 10 days of the UN Security Council voting a resolution mandating the protection of Libya’s civilians … NATO took command of a significant force of dozens of ships and hundreds of airplanes and commenced operations … While US planes flew a quarter of all sorties over Libya, France and Britain flew one third of all missions ... France and Britain played an extraordinary part in the operation, leading the pack in providing air and naval assets.

In a point related to the prior discussion of recurrence, however, the failure of the P3 to adequately lead Alliance thinking about security sector support to the Libyan state in the aftermath of OUP has been widespread. Even those who speak positively of the initial humanitarian intervention have not shied away from criticism:

We may not like it—and Obama certainly doesn’t—but even when the US itself is not particularly involved in a given conflict, at the very least it is expected to set the agenda, convene partners and drive international attention toward an issue that would otherwise be neglected in the morass of Middle East conflicts. The US, when it came to Libya, did not meet this minimal standard ... Even President Obama himself would eventually acknowledge the failure to stay engaged. As he put it to [Thomas L.] Friedman: ‘I think we [and] our European partners underestimated the need to come in full force if you’re going to do this.’

In answering a question about the “worst mistake” of his Presidency, Obama also pinpointed Libya: “Probably failing to plan for the day after, what I think was the right thing to do, in intervening in Libya.”

In sum, therefore, for the Alliance the episode underscores the importance of sustained P3 leadership in any R2P contingency. Should a new Trump administration’s “America First” mantra translate into a renewed appreciation of the United States’ position as NATO’s indispensable Ally rather than isolationism, Washington’s role will be critical here. Should it not, Britain and France will have to lead thinking about the ever-critical “political-military estimate” of a situation in order to develop response options in future R2P contingencies.

8. Verify ‘absorption capacity’ of assisted state

As the previous section suggests, although later than perhaps ideal, in July last year, the Atlantic Alliance clarified its readiness to support stabilization in post- Gaddafi Libya:

In accordance with our Wales decision, we are ready to provide Libya with advice in the field of defence and security institution building, following a request by the Government of National Accord, and to develop a long-term partnership, possibly leading to Libya’s membership in the Mediterranean Dialogue, which would be a natural framework for our cooperation. Any NATO assistance to Libya would be provided in full complementarity and in close coordination with other international efforts, including those of the UN and the EU, in line with decisions taken. Libyan ownership will be essential.

If wishing to relate this offer to R2P’s Pillar 2, it would appear to most closely align with the first of seven inhibitors to atrocity crimes as outlined in the 2014 report “Fulfilling our collective responsibility: international assistance and the responsibility to protect.” Here reference is made to establishing a “professional and accountable security sector.” In a NATO context, this clearly falls within the purview of the core task of “cooperative security” revealing its potential role in R2P implementation alongside crisis management in a Pillar 3 context.

Should a request for security assistance arrive, however, the aftermath of OUP flags an important lesson in capacity building that needs to be taken into account. Where member states and other institutions to date have made offers of assistance related to good governance, one of the biggest challenges has reportedly been lack of local institutional capacity to absorb the offers of assistance, financial or otherwise, due to ongoing uncertainty about Libya’s political institutions and a dearth of expertise. As the aforementioned RAND study observes in speaking about post-Gaddafi’s Libya:

Moreover, the institutions of the security sector were extremely weak or non-existent administratively … Worse, the Ministry of Defense had actually been dis-established by Gaddafi decades ago. The military had been run by the Chief of Staff, creating an inherent tension in efforts to build a more standard Ministry of Defense.

Although the Alliance has placed its faith in the Government of National Accord (GNA), ongoing political uncertainty and institutional limitations will have to be taken into account in any decision about defense and security capacity building should a request for assistance be received in Brussels. The same may be said for that matter of any other state asking for NATO’s prevention assistance.

9. Ensure inter-organizational coordination

The previously cited Warsaw Summit communiqué’s point of emphasis on international coordination in Libya post-OUP is an important one. It was in fact stressed throughout the execution of operation as well. For example, as NATO Defense Ministers stated in the midst of the campaign:

We will continue to coordinate with other key organizations, including the United Nations, the European Union, the League of Arab States and the African Union, and to consult with others such as the Organization of the Islamic Conference, and we encourage these organizations’ efforts in the immediate and longer term post-conflict period.

The end of the operation was little different:

This wasn’t just a… Western intervention. NATO acted only after it was clear that it had broad-based regional support, including from the Transitional National Council and the Arab League, which requested intervention. Four key Arab partners— the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Jordan and Morocco—participated in the effort. And it acted on the basis of a clear UN mandate.

These references certainly align with prevailing sentiment within the leadership of the United Nations when it comes to R2P: “We have learned over the past decade that international responses to atrocity crimes tend to be most effective when the United Nations and regional and subregional arrangements work closely together.” Yet this did not mean that practical shortcomings did not emerge during OUP. One case in point was NATO’s relationship with the African Union.

While AU member states Nigeria, South Africa and Gabon voted affirmatively for UNSCR 1973 as non-permanent members of the Security Council, as the operation dragged on, African support fractured. Growing discomfort with NATO on the part of many African countries (some who had even supported the original UN Resolution) and those within the AU senior leadership has been well documented and it is not the purpose to repeat it here. Suffice it to say, it was not that Africans oppose intervention to address atrocity crimes. The AU Constitutive Act, in fact, specifically countenances “the right of the Union to intervene in a Member State pursuant to a decision of the Assembly in respect of grave circumstances, namely: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.” Rather, concern turned on OUP outcomes morphing into regime change, a sense that diplomacy—principally the AU roadmap—had been marginalized in favour of a military approach to conflict resolution and, a feeling of a general lack of appreciation for AU leadership aspirations when it comes to questions of African security. Part of the difficulty appeared to lie in the absence of inter-institutional machinery to facilitate AU-NATO dialogue. Prospects have since improved with the May 2014 signing of an agreement which formalizes the status of the NATO liaison office to the AU Headquarters in Addis Ababa. But many other ideas to strengthen institutional ties between, for example, the Peace and Security Council (PSC) and North Atlantic Council (NAC) and between the Permanent Representatives Committee (PRC) and Political and Partnerships Committee (PPC), have yet to reach fruition. Given what NATO’s latest 2016 Summit communqué says about working with the AU on Libya, they should be revisited; and likewise before the next R2P exigence on the same continent or elsewhere arises.

10. Reflect yet act

The newly appointed UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, has been called upon “to foster a renewed debate among member states around the rules and principles under which the application of R2P should take place.” A similar call for NATO and its member states to contribute to this with particular reference to their OUP experience has been made in these pages. But as Guterres’ predecessor at the UN was quick to point out, as important as R2P conceptual discussions are, they should not “stand in the way of the imperative to move from refinement of the concept of responsibility to protect to its implementation.” “Reflect yet act” is the essence of Ban Ki-moon’s message and it is equally germane to the Alliance as it debates its role in humanitarian intervention to prevent the most egregious of international crimes. As the 2016 edition of the “NATO Lessons Learned Handbook” informs us, a lesson is only genuinely learned once it is applied across the institution:

Three Basic Steps to Learning

1. Identification: Collect learning from experiences.

2. Action: Take action to change existing ways of doing things based on the learning.

3. Institutionalization: Communicate the change so that relevant parts of the organization can benefit from the learning.

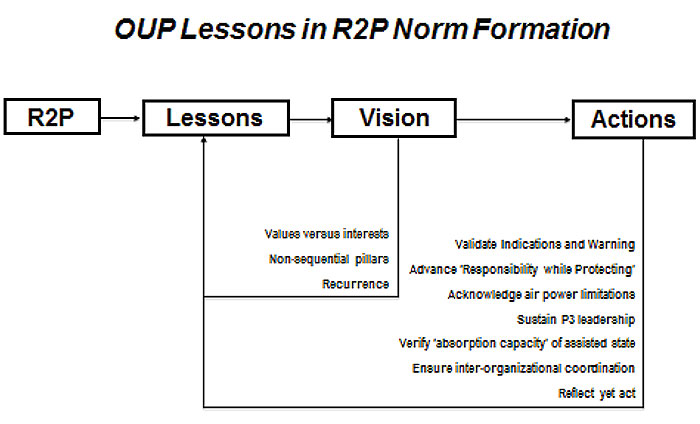

So the fundamental challenge is to act on and communicate across the Alliance the R2P lessons identified as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Conclusion

Whether working through the UN Security Council, the UN General Assembly or the Alliance itself, all NATO member states have a duty to mature R2P as it enters its 12th year of norm formation. None among them has questioned the individual responsibility to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. Nor have they questioned the obligation of the international community to assist other states in also fulfilling that responsibility and, if necessary, to intervene with UN sanction should they fail to do so. As the Libya case demonstrates, the conduct of the Atlantic Alliance, one of the few regional organizations both capable and politically willing to operationalize the coercive provisions of Pillar 3, is particularly significant to shaping what remains R2P’s most controversial element. Learning from this experience, by reflecting and acting on the ten lessons summarized in Figure 4, offers a starting point to a reinvigorated focus on an emergent international norm corresponding to NATO’s crisis management as well as cooperative security core tasks. At a juncture when a newly-minted US administration is questioning the Alliance’s relevance, this could not be more timely.

Figure 4

About the Author

Brooke Smith-Windsor, Ph.D. is the former Director of Strategic Guidance at Canada’s Department of National Defense.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.