Russian Analytical Digest No 196: Russian Security/Defense

23 Jan 2017

By Richard Connolly, Stephen Aris and Bettina Renz for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The three articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies in the Russian Analytical Digest on 23 December 2016.

Hard Times? Defence Spending and the Russian Economy

Abstract

Driven by an ambitious plan to modernize the armed forces and to upgrade the wider defence-industrial base, defence spending in Russia has grown rapidly since 2010. However, nearly two years of recession and bleak growth prospects have caused policy-makers to make some tough choices over how to allocate public resources. The recently-approved budget for the period 2017–19 envisages a reduction in overall public spending and of defence spending. While this suggests that the period of rapid growth in defence spending has ended, closer inspection of the proposed budget shows that the defence industry and the military remain important to the Russian leadership.

Russian defence spending, driven by an ambitious plan to modernize both the equipment used by the Russian armed forces and to upgrade the wider defence-industrial base, has risen sharply in recent years. However, the budget for the period 2017–19 adopted on December 9th suggests that defence spending, as a share of total federal government spending and of gross domestic product (GDP), may well decline in the coming years. Against the backdrop of Russia’s armed intervention in the Syrian civil war, and amidst a wider heightening of tensions between Russia and the West, this relaxation of the defence burden may appear surprising.

In this article, the scale of the planned reduction in defence spending is considered, along with the implications that spending plans are likely to have for the future of Russia’s plan to re-equip and modernise its armed forces, and what this might mean for Russian economic development in the near future.

From Rearmament…

The urgent need to re-equip the armed forces became apparent in the aftermath of the war with Georgia in 2008. In late 2010, the erstwhile president— Dmitry Medvedev—approved a new ten-year state armaments programme (gosudarstvennaia programma vooruzheniia, hereafter the GPV-2020) that was designed to re-equip and modernise the Russian armed forces by 2020. As well as providing substantial—and in the post-Soviet period, unprecedented—funds for re-equipping Russia’s armed forces, it was also envisaged that the GPV-2020 would revitalize the Russian defense industry through investment in the modernization of the industry’s fixed capital stock. As such, the GPV-2020 was an attempt to both modernize the Russian armed forces and to revamp the Russian defence industry. This led President Putin to express the hope that the defence industry would act as a “locomotive” of technological development in the wider economy.

As the rearmament process gathered momentum, total Russian military expenditure grew from 3.8 percent of GDP in 2010 to 5.4 percent in 2015. Within this, the amount allocated to the annual state defense order (gosudarstevennyi oboronnyi zakaz, or GOZ) grew from 1 percent of GDP in 2010 to 2.4 percent of GDP in 2015. This was augmented with state guaranteed credits (SGCs) provided via state-owned banks, as well as additional indirect funding that was channeled through other ministries, such as the Ministry of Industry and Trade, which funded the development of industrial projects with military applications.

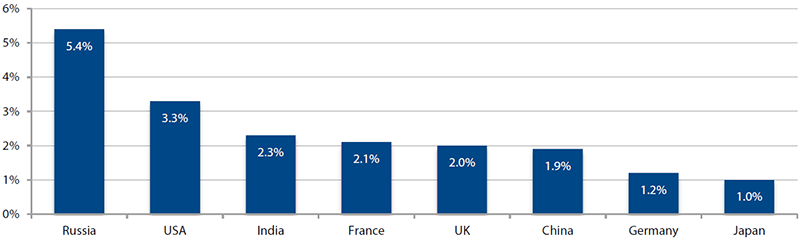

This injection of funds into the defence industry caused a reorientation in the overall allocation of federal government spending. In 2010, military expenditure accounted for 15.9 percent of federal government spending; by 2015 it had grown to 25.8 percent. In 2015, the GOZ alone (including SGCs) accounted for nearly 12 percent of federal government spending, up from less than 5 percent in 2010. With total military expenditure estimated by SIPRI to have reached around 5.5 percent of GDP in 2015, the defence burden in Russia was well in excess of the NATO average (1.5 per cent of GDP) and that of the USA (3.3 per cent) and China (1.9 per cent).

For some observers, this reorientation of defence spending was a worrying sign, contributing to the perception of a more militarily capable and threatening Russia. However, it should be understood that the rearmament process embodied in the GPV-2020 drove much of the rise in military expenditure, and this in turn was much-needed after the hiatus in defence procurement and military spending in general that occurred in the aftermath of the disintegration of the Soviet Union. Improved conventional capabilities may, for instance, reduce the emphasis that Russian defence planners place on the use of nuclear weapons in any large-scale conflict. And, lest it be forgotten, the absolute sums allocated to the Russian military remain significantly lower than either NATO to the west and China to the east.

The supplementary amendment to the 2016 budget made in October, which saw an additional RUB 780 billion allocated to the ‘national defence’ chapter of the federal budget, prompted some observers to highlight what appeared to be another sharp increase in defence spending. However, closer inspection revealed that this additional spending was not made to support current spending on operations or procurement, but instead was intended to pay down around RUB 750 billion of the principal outstanding on the SGCs that were used to supplement direct budget funding for the state defence order in previous years (the total stock of which amounted to over RUB 1.2 trillion).

The state decided to intervene before large repayments were due to be made over 2017–18, largely because a number of enterprises would have found the repayment schedule too onerous, raising the prospect of rising non-performing loans affecting the state-owned banks that had provided the loans to defence-industrial enterprises. Soon afterwards, a government decree, prepared by the Ministry of Finance, permitted the state to guarantee up to 100 percent of the debt of strategic enterprises, an increase from the 70 percent that was previously guaranteed by the state.

Both developments—the state intervention to reduce the principal outstanding on previous SGCs and the move to increase the proportion of loans guaranteed by the state— suggest that the financial situation of at least some key defence enterprises is precarious, despite the large increase in defence spending that has taken place in recent years.

…to a Change in Priorities?

After a period where the defence budget grew strongly each year, the new budget for the period 2017–19 suggests that a period of relative austerity lies ahead for the defence industry. Due to the wider, protracted economic slowdown that has afflicted the Russian economy since 2013, tax revenues have declined. Because of the desire in the leadership to reduce the size of the budget deficit, this has resulted in plans for a steady and significant reduction in federal government spending across nearly all spheres of government activity.

In 2015, federal spending amounted to 21.2 percent of GDP. Under the plans outlined in the budget, it is envisaged that the share of federal spending in GDP will decline to 18.7 percent of GDP in 2017, and eventually reach 16.2 percent of GDP in 2019. This reduction in overall spending is intended to reduce the federal budget deficit from what will probably be around 4 per cent in 2016 to just 1.2 per cent in 2019.

Since the recession began in 2015, defence spending has been cushioned from significant cuts, at least compared to most other chapters of budgetary spending (with the exception of social welfare spending). Some accounting sleight of hand has helped. For instance, the 2016 budget as outlined in the budget law envisaged a nominal reduction in spending on the ‘national defence’ budget line of just 1 percent (c. RUB 320 billion), compared to an average of 10 percent in other departments. This would have reduced the share of total (SIPRI-defined) defence expenditure from 5.4 percent of GDP in 2015 to around 4.8 percent. However, the allocation of nearly RUB 200 billion worth of SGCs to help execute the state defence order compensated for this reduction, even before the additional allocation of funds to reduce the stock of outstanding SGCs was made later in the supplementary budget.

The 2017–19 budget appears to portend a more significant reduction in the weight of the defence burden. Spending under the ‘national defence’ chapter is scheduled to decline from nearly a quarter of federal spending in 2016 (19 percent excluding the supplementary allocation of funds to pay off SGCs) to around 17.5 percent over the period 2017–19. If executed to plan, this reduction in spending should bring real (i.e. inflation adjusted) defence spending down to levels last seen around 2013. On the face of it, this halt to the rapid growth in defence spending of recent years appears to be a significant development. After all, if the Kremlin intends to curtail military expenditure, especially in an era of strained relations between Russia and the West, perhaps it will augur well for a future relaxation of tensions. However, closer inspection of the budget reveals that the reduction in funding for the defence industry may not be quite as severe as it is presented.

First, the apparently sharp annual reduction (2016–17) of nearly 30 percent in nominal terms that has been reported in some quarters is misleading. Such a large decline is a result of the inclusion of the additional funds included in the supplementary 2016 budget to reduce the outstanding principal on SGCs. If these additional funds are excluded from the calculation (so, comparing like-for-like expenditure), the reduction in spending committed to ‘national defence’ over the next year is closer to 9 percent in nominal terms.

Second, closer inspection of the planned expenditure reveals significant variation across spending on ‘national defence’. For instance, a large proportion of the proposed reduction in spending looks set to fall on the budget line ‘applied R&D (research and development) in the field of national defence’, where funding should decline from RUB 432 billion in 2016 to RUB 346 in 2017 and even further to RUB 176 billion in 2019, a cumulative decline of nearly 60 percent over three years. Most other budget lines are protected from such severe cuts, with the exception of the budget line ‘other items in the field of national defence’, under which spending on operations in Syria is believed to be funded.

Third, additional funds look likely to be made available elsewhere in the budget to compensate the OPK for cuts made in direct defence spending. For instance, an extra RUB 150 billion is allocated under the classified section of spending on the national economy. This represents a seven-fold increase on spending on the same classified section of the budget in 2016, and includes a nine-fold increase in classified spending on ‘applied R&D’. Given that a new state programme (No.425-8; “Development of the Defence-Industrial Complex”) to increase productivity in the defence-industrial complex was approved in May 2016, it is likely that this will be funded through an increase in spending channeled via the Ministry of Trade and Trade (Minpromtorg). And a further RUB 43.7 billion in SGCs has been made available to help finance the development of the defence-industrial complex. Thus, while the mechanism of funding has changed, the final beneficiary—the defence-industrial complex—remains the same.

Fourth, funding for the annual state defence order (GOZ) is forecast to decline only very slowly in nominal terms. Thus, while around RUB 1.65 trillion was allocated to the GOZ in 2016, modest annual reductions mean that by 2019 it is expected that around RUB 1.55 trillion will still be allocated to the GOZ, a large proportion of which finances procurement. This is quite a mild reduction in funding, even if inflation will erode the real value of this expenditure to bring it down to a level of expenditure last seen in 2013. Indeed, because expenditure on the overall ‘national defence’ line is expected to decline more quickly than spending on the GOZ, the share of the GOZ in ‘national defence’ spending should actually rise from 53.5 percent in 2016 to just under 58 percent in 2018 before declining thereafter.

Finally, there appears to be scope for an increase in defence spending if the wider economic situation improves. In early November the Duma approved a measure that permits the government to reallocate up to 10 percent of federal government spending towards defence and security without seeking agreement from the Duma, although apparently any extra funds cannot be assigned towards fulfillment of the state armaments programme. Because the overall budget is based on a relatively conservative oil price of $40 per barrel (Urals) over the three-year period, it is plausible that tax revenues may turn out to be higher than expected, especially if Russia and OPEC successfully cooperate to support oil prices. Government spending in Russia is highly correlated with oil revenues, so if the price of oil is higher than forecast, we should expect budgetary spending to rise with it.

Implications for the Modernization of the Armed Forces and Economic Development

It is clear that Russia’s protracted and still ongoing economic slowdown is forcing policy-makers in Moscow to make some tough decisions about how to spend increasingly scarce public resources. However, despite the mood of austerity that is reigning across most ministries, the plans for public spending over the next three years do appear designed to reduce, if not eliminate, the impact on both the military and defence industry.

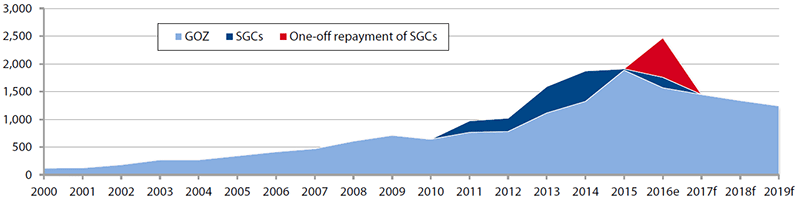

Clearly, as public spending is reined in, the rapid growth rates observed in both procurement (which, including SGCs, rose at a nominal average annual rate of over 30 percent between 2010 and 2015) and military spending more widely have come to an end. As Figure 1 shows, the peak in spending on the GOZ was reached in 2015 and is scheduled to decline over the next three years.

According to the President, the focus for the foreseeable future should be on the ‘optimisation’ of defence spending (i.e. the more efficient use of existing resources) and ‘diversification’ of defence-industrial production (i.e. a shift away from state defence orders as the primary source of sales towards civilian production), so that the defence industry can reduce its dependence on the GOZ for the vast majority of its revenues (estimated by Putin to account for 84% of defence industry revenues in 2016).

Nevertheless, the fact that the government appears to remain committed to rearmament despite the sharp reduction in overall government spending shows that the modernisation of the armed forces, along with social welfare, retains primacy among Kremlin priorities. After all, in real terms, spending on the GOZ looks set to remain at 2013–14 levels for the foreseeable future.

Thus, the re-equipment of the armed forces appears likely to continue, reflecting the political priority that this objective has enjoyed in recent years. While some individual weapon systems, such as the PAK-FA fighter aircraft and the Armata battle tank, may be produced in lower numbers than originally forecast and at a slower pace, it is still likely that significant volumes of new equipment will reach the armed forces over the next few years, enhancing the overall capability of the armed forces.

While this orientation towards defence spending, at the expense of, for instance, education and health, may well appear misguided given the scale of socio-economic challenges confronting Russia’s leaders, there are several reasons to believe that it can nevertheless be maintained.

First, Russia has very real and specific security concerns that mean it is required to bear a greater defence burden than most countries. As a result, both elite and public support for a relatively high volume of defence spending is high. These security concerns are unlikely to disappear soon, so this commitment by both elite and the wider population should be expected to persist.

Second, senior officials, including the President, have stated that once the objective of modernising the equipment used by the armed forces has been met, procurement spending will probably be scaled down to a lower level. Indeed, the statements concerning the likely focus of the new state armaments programme that should be developed by summer 2017—GPV-2025—indicate that attention will switch from large-scale re-equipment to the development of high-technology communication and information systems and new generation weapon systems.

Finally, for all the talk of Russian leaders displaying a preference for ‘guns over butter’, the fact remains that the defence burden remains an order of magnitude lower than that which prevailed during the Soviet era. While defence spending may not prove to be the locomotive of growth and technological development that Putin had hoped for, defence spending is not yet distorting economic development to the extent that it did during the Soviet period.

About the Author

Richard Connolly is director of the Centre for Russian, European and Eurasian Studies at the University of Birmingham. He is also associate fellow on the Russia and Eurasia programme at Chatham House, visiting professor at the Russian Academy of the National Economy, and editor of Post-Communist Economies.

Note: estimates on GOZ spending supplied by Prof. Julian Cooper, University of Birmingham

Additional Reading:

- R. Connolly and C. Senstad. 2016. ‘Russian Rearmament: An Assessment of Defense-Industrial Performance,’ Problems of Post-Communism.

- J. Cooper. 2016. ‘The Military Dimension of a More Militant Russia,’ Russian Journal of Economics, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 129–145.

Figure 1: Spending on Rearmament (Annual State Defence Order, GOZ), Million RUB 2015 Constant Prices, 2010–2019 (2016–2019 Estimates; Prices Adjusted for Inflation Using GDP Deflator)

Figure 2: Defence Spending as a % of GDP in Russia and Other States

Still in Search of its Place: The CSTO As a Collective Politico-Military Framework

Abstract

While most attention is centred on Russia’s use of military tools for foreign policy goals in Ukraine and Syria, Moscow’s flagship politico-military alliance—the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)— continues to fly under the radar. For the Kremlin, it represents a key tool for constructing regional politico-military unity around itself. However, recent events highlight the distinct limitations to this function. And, with Moscow’s attention increasingly focused elsewhere, it is unlikely that the CSTO will take significant steps forward in the near future.

Widespread concerns about Russia’s military power and intentions have returned to the top of the agenda for Western politicians and analysts alike, notably in relation to Russia’s “hybrid warfare” in Ukraine and bombing campaign in Syria. The growing discomfort about Russian military activities has manifested themselves in escalating tensions and posturing between Russia and NATO countries, including the repositioning of military hardware and troops vis-a-vis one another, Russia’s withdrawal from a nuclear security agreement earlier this year and fears about direct military confrontation in Syria. Against this backdrop, many commentators are explicitly, or more often implicitly, presenting the Kremlin as an effective wielder of the military tool in its foreign policy toolbox. For example, it has been suggested that Russia has altered the diplomatic context around Syria in its favour, and successfully unsettled the Eastern-members of NATO.

In the midst of the high-profile diplomatic disputes on Ukraine and Syria, Russia’s use of military tools for foreign policy goals in its South have gone largely unnoticed. As opposed to the conflictual dynamic that prevails in its policy towards its West, Russia has long been using politico-military cooperation as a central component for its efforts to consolidate its primary role in what the Kremlin has variously termed its “near abroad” or “zone of special responsibility”. While increasingly credited as an effective user of a military dimension to its foreign policy to its West, the evolution of Russia’s flagship politico-military alliance—the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO)—suggests there may be distinct limitations to the Kremlin’s ability to effectively use it in the name of region-building.

Moscow hopes that the CSTO will function as a structure to enshrine a collective political unit among its members, with Russia’s role as the primary military benefactor of the other members serving to ensure the Kremlin’s primacy as the security guarantor for these states, and for the post-Soviet space writ large. While it is now well-established and to some extent serves these goals, the CSTO’s lack of progress in establishing a reliable role for itself in the region’s security landscape has seen many question its utility and ultimately its long-term existence. In late October, the Secretary-General of the CSTO and the long-term Kremlin-insider, Nikolai Bordyuzha felt moved to write a letter refuting an article published on versiya.ru, which argued that the organisation may soon cease to exist. That Bordyuzha saw it as necessary to directly challenge this commentator’s analysis is expressive of the gap between what the organization’s officials claim is the CSTO’s every growing role and importance for regional security, and the repeated question asked by analysts and commentators: what exactly is the CSTO for? While this question has been ever-present throughout the CSTO’s lifespan, its poignancy may well be increasing as it seems clear that the focus of Moscow’s attention and importantly its finances may be shifting to other politico-military priorities, such as the continuing cost of the Syrian bombing campaign and grandiose ideas such as re-establishing military bases far from Russia. Furthermore, recent events have highlighted persistent political differences and diverging foci of attention among its members, as well as the emergence of alternatives to the CSTO.

Too Much Dominance?

The abiding feature of the CSTO as a vehicle for multilateral politico-military collaboration is the overwhelming predominance of Russia as compared to the other members. The position of Moscow as the centre-of-gravity is both a major binding agent and a source of incoherence. For all the other members, their relationship to Russia is key to their participation, with collaboration with one another a very distant (in some case, non-existing) secondary priority. Arguably the most important dimension to the organization is that the other members are able to purchase arms and military equipment from Russia at rates well below market value. As Russia is the major military supplier of all the other members, this exchange relationship constitutes the backbone to the multilateral structure. The result is what network mappers would call a simple star-shaped network, whereby the only meaningful relationships within the CSTO connect Russia to the other members.

Although instituting their predominance is integral to the value of the CSTO in the eyes of the Kremlin, they would also like the organization to make at least some functional contribution to addressing security challenges, for it to form some kind of security community and for it to be acknowledged by the rest of the world as the legitimate and authoritative multilateral security organization for the region. However, the extent of Russian predominance seems to place a limit on progress towards these latter goals. On the rare occasions the CSTO vies away from Russian-centricism, its basic political constitution becomes dysfunctional. This can be seen by the mismanagement of the long discussed appointment of a new CSTO Secretary-General. At the end of 2015, it was stated that the long-term Kremlin-insider Nikolai Bordyuzha was to step down and be replaced, reportedly by an Armenian candidate. However, at October’s annual CSTO Summit this decision was postponed for a second time, with suggestions that this was due to a lack of agreement about which member would provide the new head. The decision is now slated to be made before the end of 2016. This saga could be read as suggesting internal incoherence, which is seemingly only overcome by having a Russian as Secretary-General. While the Kremlin may be happy that it is the unifying element to the CSTO, the extent to which this is the case leads to major questions about its wider utility.

Collective Defence Without Agreement?

Aside from Russian predominance, there are clear differences in policy-positions between the CSTO members. The most pressing and fundamental is the ongoing, and recently reignited, Nagorno-Karabakh dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan. As last April’s outbreak of open conflict illustrates, this is a dispute that is never far away from outright conflict. In this context, there has been discussion about the commitments made by the signatories of the CSTO Charter to one another in terms of “collective defence”, and whether this is in anyway equivalent to NATO’s often-mentioned article 5 guarantee. The CSTO Charter certainly contains phrases alluding to some notion of “collective defence”, but the wording is at best ambiguous. While Yerevan actively seeks to promote the idea of a CSTO collective defence commitment as applicable in the case of an Azeri attack on Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia, as the major military sponsor of all CSTO activities, has retained an aloof position on the question, never openly endorsing such an understanding. This is likely in part because several of the other CSTO members implicitly and at times explicitly side with Azerbaijan on the issue. Kazakhstan’s has sought to emphasise that as the Nagorno-Karabakh territorial dispute has never been settled and thus there is no common understanding on “ownership”, this question lies outside the scope of the CSTO Charter commitment.

Irrespective of interpretations of the wording of the CSTO Charter, in practice it is difficult to imagine the Central Asian Republics either politically supporting or military committing people and resources to a CSTO operation in the South Caucasus. In this way, it is politically pragmatic for the CSTO bureaucracy and Moscow to fudge and side-step the issue on Nagorno-Karabakh. But, as a consequence, the question of the utility and purpose of the organisation is once again brought to the surface. If it is unable to respond to even a question of “collective defence”, then the active military component of the CSTO must also be in doubt in general. On the back of the CSTO’s inaction during the Osh riots (2010), some analysts ask if there are any circumstances or scenarios in which a CSTO military operation could be mounted and which would be politically supported by all of its membership.

New Alternative Military Frameworks?

These doubts about the CSTO’s operational viability as a collective military actor are also evident with regard to the potential spill over of militancy from Northern Afghanistan into Central Asia. Alongside its emphasis on countering “colour revolution” scenarios (which have been the subject of most CSTO joint military exercises over the last decade), this threat has been a staple of both Russian and CSTO discourses. Over the last year, this concern has been further amplified, due to the increased intensity in fighting in the areas of Afghanistan neighbouring Central Asia. The city of Kunduz, close to the Tajik border, has fallen to and been retaken from Taliban-forces twice in the last year. While Russia is interested in supporting border security in all the Central Asian Republics neighbouring Afghanistan, only Tajikistan hosts both Russian troops and a military base under the auspices of the CSTO. In early autumn, both the head of Russia’s Security Council and CSTO-head Bordyuzha visited Tajikistan for talks about the impact of the deteriorating situation in northern Afghanistan. Indeed, several CSTO military exercises have been held in Tajikistan in recent years, modelled on responding to the threat of militant groups crossing from Afghanistan.

Yet, doubts remain over whether the CSTO would act collectively in response to such a situation. It would seem highly unlikely that Armenia or Belarus would be willing to commit troops to a region they see as very distant from their own, while Tajikistan’s willingness to permit the troops of other Central Asia Republics to fight on its territory is also far from certain. Ultimately, it would likely more come down to the attitude of Russia and their relationship to the Rahmon regime. In which case, it is feasible that the Russian security apparatus may simply dispense with the multilateral paraphernalia of the CSTO and opt for a distinctly unilateral approach.

Furthermore, the doubts about its reliability as a collective military actor seem such that the Rahmon regime is not content to rely solely on the CSTO as its emergency military backup. Recently, it has begun exploring a new military-security relationship with China. Such engagement was already in evidence within the format of the SCO, and its “peace mission” military exercises. And, certainly, the CSTO-SCO relationship is a rather obtuse and ambiguous one. The China–Tajik security relationship has now, however, expanded beyond the SCO, and into formats of which Russia is not a participant. In late summer 2016, a joint statement by China, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan was issued announcing the launch of a Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism. A Chinese-driven initiative, it aims at coordinating the efforts of military leaders from the four states towards the common goal of tackling terrorism and extremism. Under this umbrella, China and Tajikistan held a joint bilateral military exercise in Tajikistan’s Gorno Badakhshan province in October.

The reaction from some commentators in Moscow has been less than positive, seeing these developments as violating an informal understanding that China leaves military concerns in Central Asia to Russia and the CSTO. And, also that Tajikistan, as a member of the CSTO, should not be engaging in joint military exercises outside the scope of the CSTO. Ultimately, China’s ever increasing importance to Russia on all manner of other issues means that Russia will not seek to make this a problematic area in their relationship. Therefore, in spite of Moscow’s discomfort with the idea, the Kremlin and the CSTO may have to get used to the presence of alternative Chinese military-security initiatives in Central Asia. A trend that may well be reinforced by the recent terrorist attack on the Chinese embassy in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan. While the exact details of who conducted this attack and in whose name are unconfirmed, it seems to have been carried out by a transnational network of extremists related to East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) traversing Syria, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. This has led to speculation that this event may precipitate a more activist security policy towards Central Asia from China. And, thus, potentially that the CSTO may be facing competition in its core market of Central Asia.

Political Capital on the International Stage?

While its utility, reliability and effectiveness as a collective security actor has always been seen as limited, it has been widely noted that the CSTO also has another important function for Moscow: international political symbolism and recognition. One of the CSTO’s primary functions is to present itself as the main multilateral regional security structure in the post-Soviet space, and for this to be recognized by those outside the region. And, in so doing, gain recognition from NATO, the EU and other regional organizations as a legitimate peer. However, such recognition has not been forthcoming from the West, which has largely ignored the CSTO and even questioned its legitimacy, suggesting that its Russian-centric nature means that it is little more than a vehicle to assert Moscow’s geopolitical pre-eminence over its proclaimed “zone of special responsibility”. The frustration at this lack of reciprocal recognition was openly articulated by Belarus’ President Alexander Lukashenko at this year’s annual CSTO summit, in which he commented that instead of asking the world to recognize it, the organisation should act in a way that forces the world to recognise it. This statement should not be understood as a threat, but rather in the context of his wider comments suggesting that the CSTO Summit is a waste of time, because its discussions do not lead to any tangible agreements among the members.

Against this backdrop of negativity over its status, one recent positive development from the perspective of Moscow has come in the form of a UN Security Council meeting to discuss UN cooperation with the CSTO, CIS and SCO. At this meeting, the CSTO Security-General, Bordyuzha addressed the UNSC outlining the CSTO’s activities (with the CIS and SCO heads doing likewise), and the Belarusian representative to the UN (Belarus is currently the acting President of the CSTO) speaking on behalf of the CSTO membership. The event was hailed by the Russian Foreign Ministry as a signal of CSTO’s growing role in the world.

The Russian speaker, at the UNSC meeting, also noted that the lack of information about the region has led to misinterpretations of the CSTO, further adding that some UNSC permanent members “have been attempting to artificially marginalize those organizations, seeing them as geopolitical competitors”. The representative from Ukraine, which is a non-permanent member of the UNSC for 2017, offered a very different interpretation, noting that the CSTO is “pretending that there is no ongoing Russian aggression against Ukraine, no occupation of Crimea, no de facto occupation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, and no war crimes committed against the Ukrainian and Georgian peoples”. These sentiments were echoed by the US speaker. As these contending voices suggest, the prospect for an open political acknowledgement and recognition of the CSTO as the primary and a legitimate collective security actor for the post-Soviet space is no closer to be realized.

At the same time, the CSTO is actively engaged in various collaborative activities with the UN, including the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and UN Regional Centre for Preventive Diplomacy for Central Asia. With the CSTO pushing for recognition as a UN authorized peacekeeping force for UN mandated security operation. While it is difficult to foresee the UNSC’s Western members endorsing such a status, the CSTO is seemingly making some progress toward this in their relationship with the UN bureaucracy. To this end, Moscow will likely continue to invest at least some resources into promoting the political symbolic role of the CSTO, irrespective of progress in its function as an active security-guarantee for its members.

Conclusion

In contrast to many recent depictions of the Kremlin as a masterly player of its military card to realize political goals in Eastern Europe and the Middle East, the evolution of the CSTO suggests that there are distinct limits to Moscow’s capability to use military coordination as the basis for integration in the post-Soviet space. The CSTO is certainly not without utility for Moscow, as it positions Russia as the hub of a network of military relationships, mostly around arms sales. It also supports the CSTO’s function as a multilateral politico-military actor, by spearheading the formation of collective military forces and conducting regular military exercises. However, there are distinct limitations to the extent of CSTO unity due to internal differences amongst its membership and their doubts about the reliability and effectiveness of it as a tool to address what they perceive as the main security threats they face. To further develop and consolidate the CSTO as a multilateral politico-military structure would require Moscow to double down on its investment of financial, diplomatic and political resources into its development. However, the signs are that the Kremlin’s attention is increasingly being drawn to events and goals beyond the scope of the CSTO, and that it is thus content for the CSTO to continue to function in its current limited form.

About the Author

Stephen Aris is Senior Researcher at the Center for Security Studies, ETH Zurich.

Further Reading

- Joshua Kucera, external pageThe Bug Pitcall_madeblog on EurasiaNet

- Stephen Aris, ‘Collective Security Treaty Organisation’ in James Sperling (ed.) Handbook on Governance and Security (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2014)

Russia’s Modernised Military: Lessons from Crimea and Syria

Abstract

The Russian military’s enhanced capabilities have caused fears of further military aggression and expansionism. However, significant limitations in Russia’s ability to project military power on a global level pertain. Assessments of the implications of Russia’s modernised military for international security should focus on the leadership’s possible future intentions for the use of force, rather than on capabilities per se.

Introduction

During the operations leading up to the annexation of Crimea in spring 2014 and the subsequent and ongoing air operations over Syria, Russia demonstrated a range of new and improved military capabilities it had acquired in the course of the modernisation programme launched in 2008. Although these improvements are certainly notable, it is also clear that the modernisation of its military is an ongoing process that is by no means complete and significant limitations remain, especially compared to the militaries of more technologically advanced countries, and the United States in particular. Arguably, what matters more for international security and for the West’s consideration of appropriate policy responses to Russia are not improved capabilities per se, but the country’s new confidence in its military as a tool of foreign policy and possible future intentions for using this tool, which are far from certain.

Transforming the Russian Military into a Flexible Tool of Foreign Policy

Up until the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the West had largely written off Russia as a serious global military actor, especially when it came to its conventional capabilities. It was clear that the country’s capabilities to project power globally had been massively reduced and there were serious shortcomings in its armed forces’ preparedness, equipment and training especially when it came to dealing with smaller-scale contingencies or limited wars. These shortcomings were painfully demonstrated during the wars in Chechnya and to an extent also in Georgia in 2008, where Russian forces were criticised for the use of excessive force, problems with command and control and especially a lack of coordination between different arms of services, resulting in excessive casualties and friendly fire incidents. The absence of even basic modern technology commonly used by Western militaries was also noted. The Chechen campaigns and Georgia war were fought largely like conventional, large-scale operations where Russia relied almost entirely on physical and numerical superiority over the opponent and on overwhelming, blunt force.

Having said this, when it comes to the sheer potential to use destructive military force, the weakness of the Russian armed forces before Crimea should not be overstated, just as its strength today should not be exaggerated. Even before the 2008 reforms, Russia was by far the dominant military actor in the former Soviet region. Even throughout the 1990s, Russia was able to use military force in its immediate neighbourhood with impunity and, although its operations were cumbersome, the country never risked comprehensive defeat. On a global level, too, Russia retained a massive destructive and offensive potential, at least in theory, in the form of its strategic nuclear arsenal. Unlike its conventional capabilities, the strategic nuclear forces remained always competitive with those of the United States. Given the ongoing discrepancies in Russian conventional capabilities vis-à-vis NATO and the West, it is clear that the achievements of the 2008 modernisation programme have not changed the global power balance substantially. The central objective of the 2008 military reforms was to overcome the shortcomings of the Russian armed forces had experienced in operations since the early 1990s, all of which were small-war like scenarios and limited wars. The reforms sought to transform the Russian armed forces from a large and unwieldy military that was outdated in many respects into a force that was more ‘useable’ in small wars and insurgencies, which it had not performed well in during recent decades. In other words, the central aim of the modernisation programme was to turn the Russian military from a blunt instrument into a flexible tool of foreign policy. Towards this aim, relevant structural reforms were implemented, new equipment was procured and training was adjusted. These changes, it was hoped, would make the Russian armed forces more rapidly deployable, better coordinated and better prepared to deal with the requirements of smaller-scale contingencies.

Lessons from Crimea and Syria

Russia’s operations in Crimea and in Syria clearly demonstrated that this refinement of the Russian armed forces has yielded considerable success. Unlike the blunt force used in Chechnya and Georgia, barely any destructive military force was used in Crimea and military planners relied instead on an information campaign that was met with open arms by the majority of the local population, on special operations forces to secure important infrastructure, and also a show-of-force approach in the form of large-scale exercises conducted close to the Ukrainian border. In Syria, additional new capabilities have been revealed. For the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia launched an out-of-area operation. This took the form of a heavily technology-dependent air campaign similar to operations conducted by US-coalition operations, which Russian military strategists had admired since the 1991 Gulf War. In the course of the Syria operations Russia displayed air- and sealift capabilities few observers thought it possessed and the absence of which would have made a similar operation simply impossible ten years earlier. Both Crimea and Syria also showed significant improvements in coordination. In Crimea, a variety of military and non-military tactics were skilfully combined and much improved air-to-ground coordination in Syria meant that Russia to date has not lost a single aircraft over the theatre of operations, in comparison to Georgia, where seven aircraft were shot down in friendly-fire incidents over a period of five days. Having said this, in autumn 2016 two fast jets were lost in short succession in accidents during attempts to land on Russia’s only aircraft carrier in the Mediterranean Sea, demonstrating clearly that technological problems persist. The 2008 reforms clearly have transformed the Russian armed forces into a more flexible instrument of foreign policy, where force levels and relevant tactics can now be fine-tuned to the specific objectives of various situations. It is important to bear in mind that both Crimea and Syria were limited operations in scale and scope and as such tell us little about Russia’s ability to project military power globally on a larger scale. Given ongoing problems with desired manpower levels, the procurement of equipment in sufficient quantity and quality and economic stagnation, it is highly unlikely that Russia will be able to launch and sustain an out-of-area operation involving ground forces on the scale of US coalition operations in Afghanistan and Iraq now or in the foreseeable future.

What are Russia’s Intentions?

In terms of lessons to be identified from Russian military actions in Crimea and Syria, what matters more than improvements in capabilities—although these are not insignificant—is the country’s renewed confidence in the military as a foreign policy tool and the leadership’s potential intentions for how to use this instrument in the future. It is likely that the success of the Crimea operations, which transformed the image of the Russian military both domestically and internationally, has supported the leadership’s decision to launch the air operations over Syria. Generally, it is likely that Russia’s decision to use military force in certain circumstances will be taken more easily in the future, when ten years ago there would have been a reluctance to do so, because of doubts about having the capabilities required to succeed. The air operations in Syria simply would not have been possible ten years ago, even if there had been the political willingness to engage in such a conflict. Russia’s improved confidence in its armed forces, however, does not necessarily translate into the intention to use military force as the foreign policy instrument of choice, or for expansionist aims, as some observers have feared.

It is impossible to estimate Russian future intentions regarding the use of military force for certain and intentions can also change over time. However, some possible lessons can be drawn from Russia’s use of military force as a foreign policy instrument throughout the post-Soviet period. As discussed above, even before the 2008 modernisation process and the annexation of Crimea in 2014, Russia was the dominant military actor in the former Soviet region. It used military force towards the achievement of various objectives in this region on several occasions, when it perceived this to be in its national interest. This included various ‘peace-enforcement’ operations during the 1990s (South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Transdnistria and Tajikistan) and the war with Georgia in 2008. On other occasions, Russia did not get involved militarily, such as the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh or the unrest in Kyrgyzstan in 2010, because other foreign policy instruments were seen as more suitable. On no occasion before the Crimea annexation had Russia used military force to expand its territory, even if it had the opportunity to do so, such as in the aftermath of the 2008 war with Georgia. There is every reason to assume that Russia will continue using military force in various situations in the future. However, it is likely that, as was the case in the past, Russia will continue doing so in pursuit of specific foreign policy objectives and interests.

A central objective of Russian foreign policy and key to its national interest has been and continues to be the maintenance of the country’s Great Power status, also militarily, and the perceived need to be granted this status internationally. Both the operations in Crimea and Syria have considerably contributed towards the achievement of this objective, as Russia is yet again seen as a serious military competitor. The use of military force for expansionist aims, especially in situations where this could lead to a direct conflict with the US/ NATO, would appear to be counterproductive within this context, not only given the ongoing limitations of Russia’s military power in global perspective, but also because it would seriously threaten not only Russia’s Great Power status, but the existence of the state itself. This is not to say that such a conflict is outside of the realm of possibilities, but it seems likely that it would be the result of escalating tensions, and not of an expansionist act of aggression.

Conclusion

In order to avoid potentially alarmist conclusions, the possible implications of Russia’s re-emergence as a global military actor need to be assessed bearing in mind that states today maintain strong militaries not only for the fighting of wars and expansion of territory. Clearly, prestige and image are an important factor, also or maybe especially for Russia. This is an important point when it comes to West’s consideration of appropriate policy responses now and in the future: inconspicuous Russian displays of military power in the form of ‘swaggering’ or brinkmanship to enhance its international image cannot be simply deterred by military force. Attempts to do so could even encourage further swaggering and increase the danger of unintended escalation in the longer term.

About the Author

Dr Bettina Renz is an associate professor in the University of Nottingham’s School of Politics & International Relations

Perceptions of the Significance of Military Power

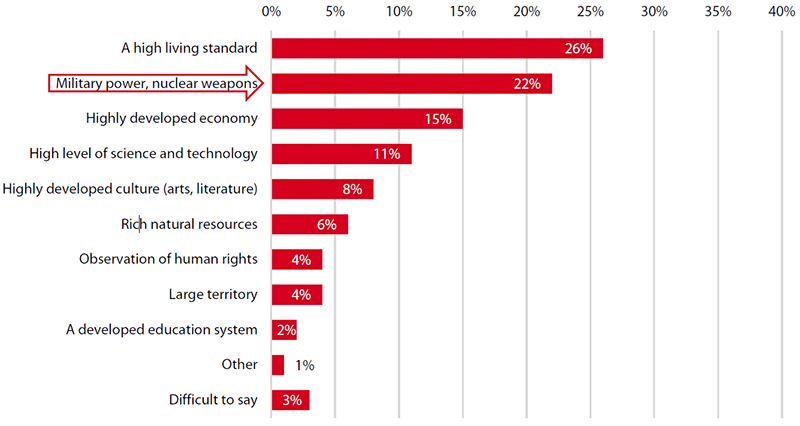

Figure 1: What Should a State Possess in Order to Be Respected by Other States?

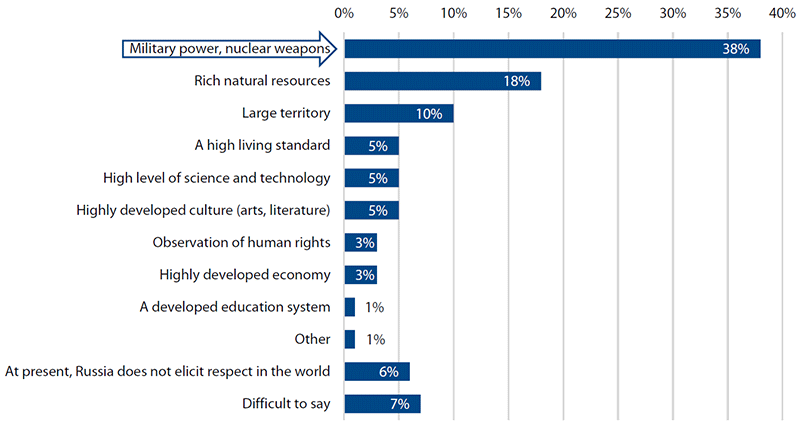

Figure 2: What Elicits At Present Respect for Russia Among Other States?

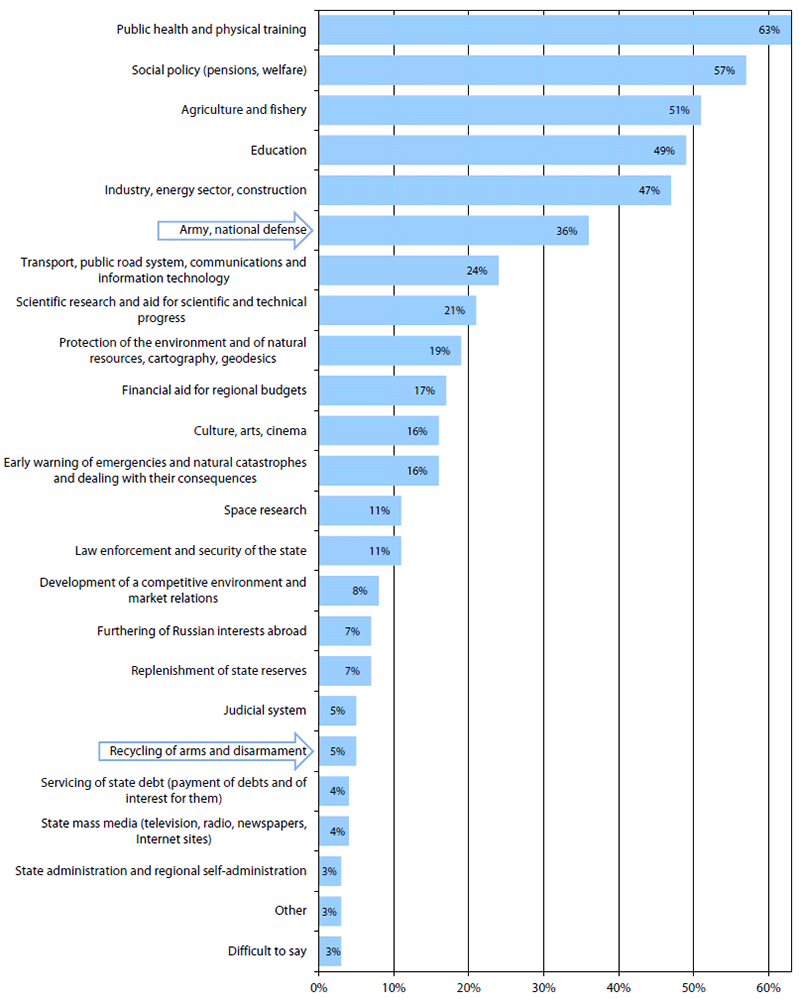

Figure 3: Which Items of the State Budget Should Russia Finance First and Foremost?

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.