Intervening Better: Europe’s Second Chance in Libya

30 Jun 2016

By Mattia Toaldo for European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)call_made in May 2016.

Summary

- The new unity government in Libya gives Europeans and Libyans alike a second chance at getting the transition right, after the failures of the post-Gaddafi intervention.

- Military intervention alone will not be enough to stabilise Libya. Its security problems are fuelled by domestic problems, such as the economic crisis and divisions between rival forces in east and west Libya, and by the meddling of regional powers.

- European countries, and their allies in the region, are making things worse by supporting rival militias to fight ISIS, which removes their incentive to back the unity government.

- To stabilise Libya, the EU and its member states will need to make tough political choices rather than just providing capacity-building programmes or sending Special Forces. This may mean that need to take a hard line some of with Europe’s top allies in the region.

- Europe should focus on five areas: the economy; reconciliation of rival factions and devolution of power; a diplomatic off to ensure that Europe’s allies back the unity government; supporting a Libyan joint command against ISIS; and implementing a joint EU-Libyan plan on migration.

Libya is at a dangerous turning point. The post-Muammar Gaddafi transition has divided the country between three rival governments and dozens of armed groups. Once one of Africa’s wealthiest nations, Libya is now bleeding cash, in desperate need of humanitarian aid, and threatened by Islamic State (ISIS). Worse, from a European perspective, its chaos threatens to unleash greater migration flows and terrorism on Europe.

The recent creation of a national unity government is an opportunity to address these threats. Libya is a massive security problem, just a few hundred kilometres south of the European Union’s borders. But this is the result of domestic political and economic dynamics, which can be addressed only through the establishment of a strong unity government. These dynamics are made worse by the interference of some of Europe’s top allies in the region.

The EU and its member states, in close coordination with Washington and other allies, should push Prime Minister Faiez Serraj to address the domestic drivers of instability, focusing on economic recovery and reconciliation with rival forces in the east of the country. EU member states will have to choose whether to stabilise Libya at the cost of taking a tough line on their allies in the Middle East, or acquiescing in the unacceptable behaviour of some of these allies, who signed statements recognising the unity government but then supported rival administrations.

The first section of this paper discusses how the West can best intervene in Libya. In the past year, there has been increasing talk of military intervention within Europe and in the United States. On the ground, an informal intervention is already being carried out by Special Forces, undermining the unity government. The second section argues that these piecemeal informal intervention efforts have created a rush by rival armed groups to become the “Peshmergas of Libya”, undermining the solidarity which is essential to effectively fight ISIS. A strong unity government is vital for addressing Libya’s three intertwined emergencies, which are discussed in the third section: the economy, migration, and ISIS. The last section gives recommendations to policymakers in the EU and its member states, grouped in five baskets:

- Dealing with the economic emergency. This will be the litmus test for Serraj, as economic collapse could have a domino effect, increasing migration flows and strengthening ISIS.

- Addressing the institutional crisis. Libya still has at least two rival administrations, undermining the unity government.

- Leading a diplomatic offensive to preserve and consolidate the unity government.

- Supporting reform of the security sector and fighting ISIS.

- Coping with the migration crisis, in cooperation with the Libyan government.

How to intervene in Libya

Since early 2015, the Western media – and officials – have been talking more and more about the need to intervene militarily in Libya to fight ISIS and to support the nascent government.1 However, under UN Security Council Resolution 2259, any form of military assistance to Libya must be requested by the legitimate Libyan government. Europeans expected the new government to make this request once it had installed itself in Tripoli, but it is now clear that this is unlikely, at least for the time being.

It is not just a Security Council resolution that is stopping Europeans and the US from an open intervention in Libya against the will of the recognised government. This would require a level of force that neither the US nor Europe is willing to commit – and it’s not clear that even a massive intervention would work without the consent of Libyan authorities.

After more than a year of UN-led negotiations, Libyan politicians signed the Libyan Political Agreement on 16 December 2015. The deal creates a nine-member strong Presidential Council (PC), which functions as the head of state, and a Government of National Accord (GNA). Headed by Prime Minister Serraj, the Council has established itself in Tripoli but is still facing two rival governments, one in Tripoli and one in Tobruk.

However, Serraj has control of the major economic institutions and the support of key local councils. This is enhanced by a number of statements and high-level visits by international bodies, signalling that his Presidential Council and the nascent Government of National Accord are the country’s sole recognised authority.

This opens a new phase of Western, particularly European, engagement with Libya. Europeans now have the partner they were asking for, namely a national unity government ruling from the capital. The new government is the most credible and realistic solution to many of Libya’s problems, and, in turn, those of Europe – particularly ISIS and migration. The West should take care not to burden it with a laundry list of unrealistic demands, from stemming illegal immigration to fighting ISIS. Instead, it should concentrate on helping to strengthen the government’s political control over the country.

In many Western capitals, policymakers are under the illusion that counterterrorism efforts can be carried out in isolation from other forms of engagement. But today, as in 2012, counterterrorism disconnected from a political process will not help Libya. The EU and its member states have to step up their political engagement, mediating, pressuring the factions to compromise, and acting forcefully to deter interference from regional powers that could lead to a new escalation.

The US and several European countries have been carrying out Special Forces operations in Libya for many months now, mostly for the purposes of fighting ISIS. The presence of US forces in Misrata and eastern Libya, and French and British forces in Benina airport and Tobruk, has been confirmed to the author by four different Libyan and Western sources. Italy is reported to have a large number of intelligence operatives in western Libya. These operations could be expanded, particularly if they are judged to have an impact in combating terrorism.

Looking for Libya’s Peshmergas

Western military intervention via Special Forces is already underway in Libya, without formal authorisation from the unity government. Instead, the US and some large European countries seem to be working directly with specific Libyan armed groups: above all, the city-state of Misrata and General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army. This works against the political efforts to strike a power-sharing deal including these groups. Each group involved in these bilateral relations is working on the assumption that they will become the equivalent of the Iraqi Peshmergas. That is, in exchange for fighting (or pretending to fight) ISIS, they expect to receive weapons and political support – even a de facto recognition of their autonomous control of territory.

A clear example of this phenomenon is the help from Egyptian and French Special Op forces to Haftar’s Libyan National Army, which has been advancing on Benghazi since February. This type of direct support from abroad has strengthened the sense of many politicians and military leaders in eastern Libya that they don’t need to strike a power-sharing deal with the forces now supporting the unity government – first and foremost Misrata – in order to have good relations with the US and Europe.

Not by chance, the House of Representatives has repeatedly failed to take two crucial steps to move the political process forward: voting on the Government of National Accord, and amending the constitutional declaration to implement the Libyan Political Agreement. On at least three occasions, a minority of MPs close to House Speaker Agila Saleh and General Haftar have physically blocked other MPs from voting in support of the Serraj government and the agreement.

On the other hand, US and European attempts to pressure Serraj and the Presidential Council to give a green light to other forms of military intervention have run up against two political realities in Libya:

- The Presidential Council is portrayed by its opponents as a foreign puppet, installed in Tripoli only to give the go-ahead to military intervention. Serraj is unlikely to request any form of Western military intervention for the time being, to avoid giving weight to these accusations. He made this explicit to several European foreign ministers who visited him in April 2016.2

- Military intervention would require a number of political decisions on the structure of Libya’s security sector, so that it could either fight ISIS or receive training from foreign forces. The Presidential Council would have to decide on a new military leadership and a national security council. But to do this, it needs the power-sharing deals that are hindered by the West’s use of Special Forces and the direct relationships with the various potential “Peshmergas of Libya”, among other things.

Stepping up political efforts

There is no doubt that force is needed to eradicate ISIS from Libya, and that the unity government will need foreign assistance to build a credible and accountable security sector capable of subduing the hundreds of militias in the country. Yet these are not mere technical decisions, and they cannot be solved with a capacity-building exercise. These are deeply political efforts. Reforming Libya’s security sector means reforming Libya’s entire power structure, which in turn affects the role that regional actors play in the country.

Instead of pretending that their Special Ops interventions will not harm the political process, the EU and its member states should bring their military strategy against ISIS into line with their support for the unity government. Europe should use its military action to create incentives for a political deal, which is needed to eliminate the ungoverned spaces in which the militants thrive.

This means three things:

- Continue high-level coordination through forums including the International Support Group (ISG) that the US and regional powers created in Rome in December 2015. Anti-ISIS efforts by the US and by single EU member states risk cutting against one another and undermining a political strategy. These efforts must at least be coordinated among the main EU actors in Libya, in line with their political goals and overall EU and UN positions. Europeans would then be in a better position to work in the ISG with the US and Arab allies.

- Keep up the pressure on regional powers to curb their interference in Libya and address the drivers of violence and political stalemate, working through the ISG and other forums. Europeans can do a lot to help the UN Special Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) to overcome the current bottlenecks in the implementation of the Libyan Political Agreement. Concerted European and US efforts to curb the growth of parallel economic institutions working for the rival government in Tobruk are an important driver of unity – for example, preventing their oil shipments from docking in European ports or taking out insurance policies in Europe.

- The EU and its member states can help the nascent unity government to address the main drivers of the current crisis, particularly the economic factors, which are the single most important element accelerating the country’s slide into chaos. Providing economic advice and capacity building, as detailed below, must go hand in hand with steps to improve the security situation. Insecurity damages the economy – for instance, by stopping oil production – but a collapse of the government’s capacity to pay salaries could decisively damage the security situation, pushing militias to join ISIS.

The most effective response to the rise of ISIS in Libya is the construction of an accountable Libyan state with an effective security sector – and there is no credible alternative to a UN-backed power-sharing deal to accomplish this. Without an accountable Libyan state, the West will be condemned to fighting an endless war in Libya against ISIS or future extremist groups.

A more politically solid unity government will be in a better position to deal with the problems that Europeans care about, including people smuggling. This is not to say that nothing can be done against ISIS in Libya in the short term. Quite the opposite: the anti-ISIS fight could strengthen the political process and vice versa. For instance, efforts by the Presidential Council to create a Military Joint Command – coordinating armed groups loyal to the unity government to fight ISIS – can both help the security situation and strengthen the political process by providing an example of power-sharing.

Libya’s three intertwined emergencies

The economic and humanitarian crisis

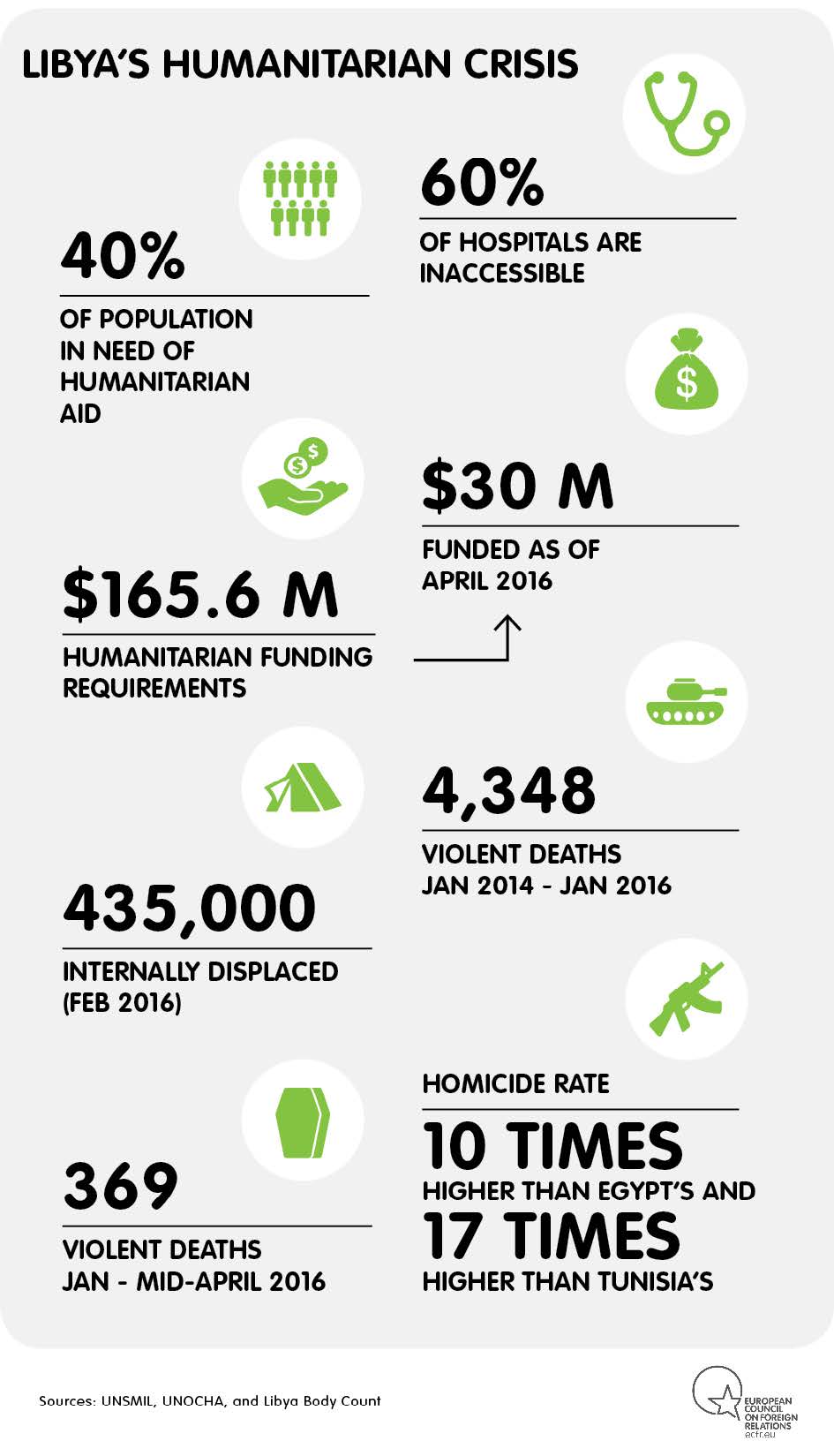

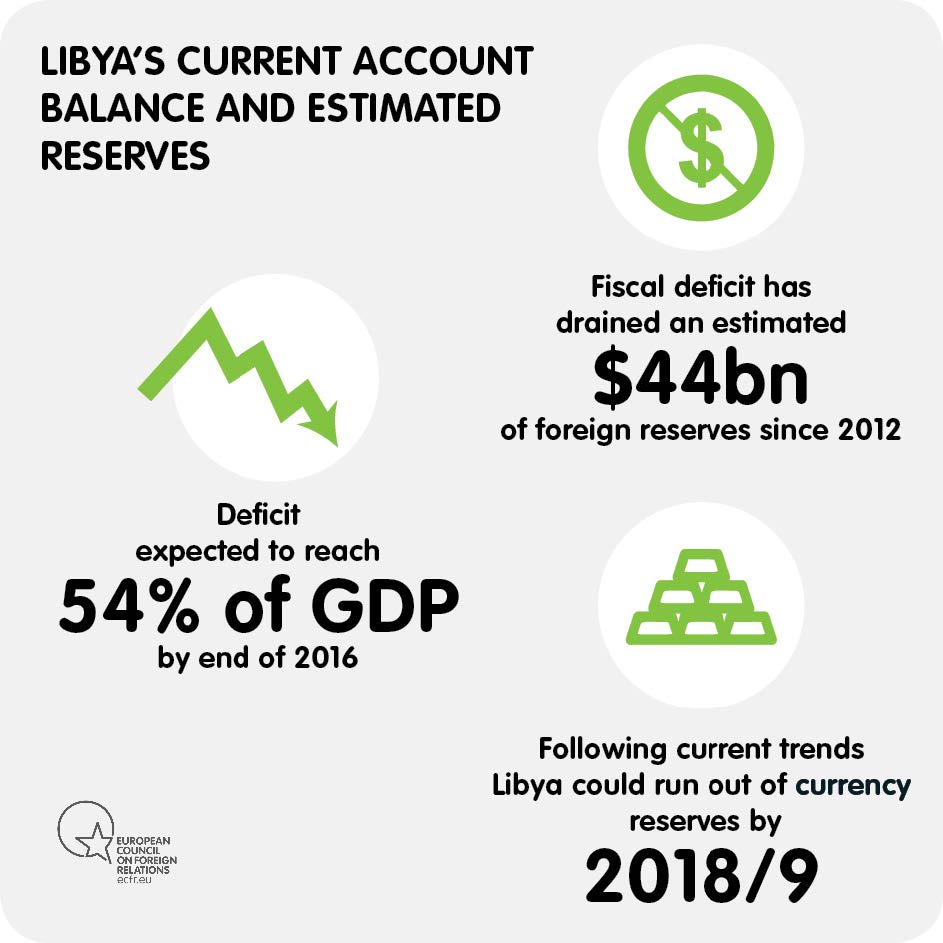

Until a few years ago, Libya was a wealthy country. Today, more than 40 percent of the population needs humanitarian assistance.3 The government deficit is expected to reach 54 percent of GDP by the end of fiscal year 2016.4 Libya has been depleting its foreign currency reserves. In 2014, they stood at more than $100 billion and are now estimated at around $50 billion.5

High government spending, particularly on salaries for the bloated security sector and militias, has contributed to this budget crisis. Spending on salaries rose from 24 to 40 percent of total government expenditure between 2012 and 2013, when most anti-Gaddafi militias were put on the government payroll. But the most important factor is the steep decline in oil production, which now stands at one fifth of its level under Gaddafi, due to damage inflicted by fighting and by ISIS attacks on production.

Libya is also suffering from a severe cash crisis. The country does not lack liquidity, but circulation is limited because the population does not trust banks. Rising inflation and the growth of the informal sector are also behind the cash shortage, which is currently Serraj’s most serious problem in terms of public opinion.

It is essential for his political survival that both the humanitarian crisis and the cash shortage appear to be at least on their way to recovery by the time Ramadan begins in June, to avoid outrage from a population unable to buy supplies for the holiday.

The rise (and fall?) of ISIS

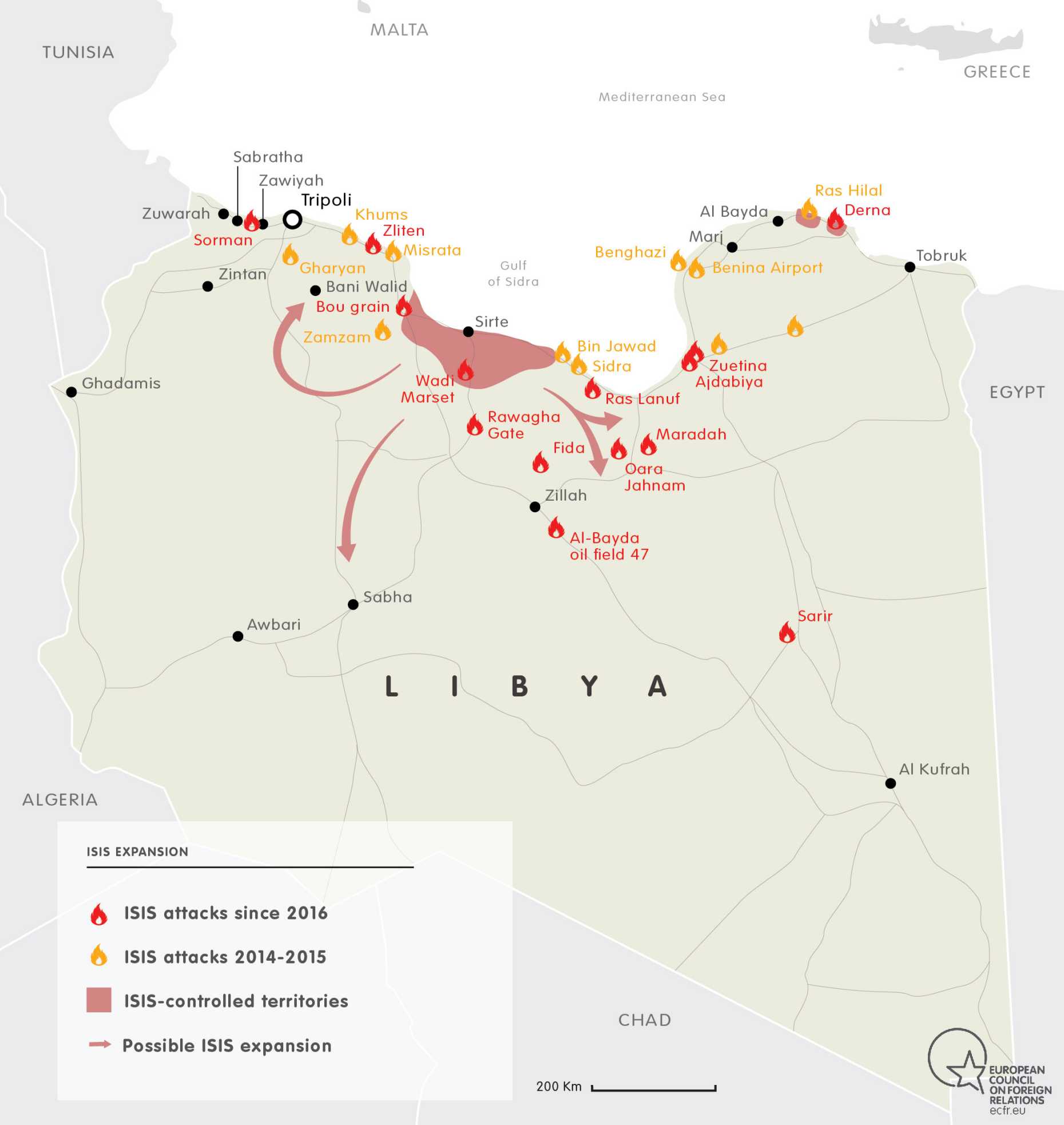

ISIS began to move into Libya in 2014, establishing its first base in the eastern town of Derna and then creating a contiguous zone under its control in Libya’s central Mediterranean coast, centred around Sirte, Gaddafi’s hometown. The organisation is already powerful and could continue to grow in Libya.

On the other hand, ISIS has not gained political traction among the vast majority of Libyans, reducing its capacity to recruit and expand. Though it has made small advances west and east of Sirte, the group has been expelled from most population centres outside of the area surrounding Sirte: Derna, Sabratha, and Benghazi are the clearest examples. In most cases, it was a coalition of local forces that forced the militants out of town. Nevertheless, a collapse of the unity government – and, crucially, of the Libyan government’s ability to pay salaries – would open the gates for ISIS to expand. Its recent defeats present an opportunity to get rid of the group and a lesson in how to fight them. But they are far from a signal of its ultimate decline.

ISIS may be suffering a short-term crisis in Libya, but it has a huge potential to expand in the country. Libyans and Europeans need a common political strategy to defeat this jihadist organisation.

Migration

Uncontrolled migration through Libya is a cause of renewed concern among Europeans. There are no accurate figures on the number of migrants that could make their way through Libya in the coming months. But some basic assumptions should guide policy:

- The number of illegal crossings via the Central Mediterranean route – of which Libya makes up the biggest part – jumped from almost 60,000 in 2012 to 170,000 in 2014, remaining relatively stable in 2015.6 The surge was overwhelmingly made up of the influx of Syrian refugees, who greatly increased the capacity and wealth of Libya’s people smugglers as they were more numerous and wealthier than their previous customers – African migrants.7

- Two circumstances could push up numbers again: either the Syrians return to using Libya as their main gateway to Europe, or another event, similar in magnitude to the Syrian war, increases the flows through Libya.

- Libya is traditionally a destination as well as a transit country for migrants, so it is not farfetched to think that if its economy gets even slightly back on track it could again absorb more than one million migrants, as it did until 2013.

- The appalling conditions of migrants and refugees in Libya, including in detention centres nominally under government control, are one of the main drivers that push migration from there to Europe.

Rather than panicking about “millions” of Africans coming through Libya – a fear stoked by Libyan politicians and by Europe’s tabloid press8 – the EU and its member states should focus on the patterns and drivers of migration. This involves early identification of push factors (like a civil war), boosting Libya’s capacity to absorb economic migrants, and making sure that Libya’s authorities respect the human rights of migrants and control the borders.

Recommendations

Given Libya’s chaos and insecurity, the West’s natural response is to put “security first” and focus on supporting the central government’s ability to control its borders and build a national army. The problem is that the West already tried this strategy between 2011 and 2014 – and it failed.9 Libya’s insecurity is the result of a complex interaction between political, economic, and military factors, both domestically and from the region.

The EU and its member states should act across five different policy baskets. In terms of priorities, the economic crisis should come first, as it is a crucial opportunity for the unity government to show the population that it can deliver. In addition, failure to resolve the economic woes will exacerbate the humanitarian crisis, increase migration flows, and promote the growth of ISIS. Second, political reconciliation is crucial, not only to keep violence down but also to make Libya’s institutions work. Third, the EU and its member states should act on the regional drivers of violence and chaos in Libya. Acting on these three elements first will help Europe to address its two most pressing concerns in Libya, namely security and counterterrorism on the one hand, and migration on the other.

Economy first

Help Serraj to address the cash crisis

There are only a few weeks left before Ramadan begins in early June. To keep the support of the people and show that he is in charge, the prime minister and his government need to show that they can address the current liquidity crisis.

Liquidity per se is not lacking – the problem is circulation, due in part to lack of trust in the banks. Europe should help the Libyan government and its central bank to guarantee deposits up to a certain level, in order to encourage Libyans to keep their money in banks rather than under their mattress. To this end, the EU could work through the UN to release some of the Libyan assets frozen in 2011. Another measure to push Libyans to circulate their cash would be the creation of bonds by the Central Bank of Libya (CBL) with interest rates above inflation. The EU could give technical support to the CBL to put this in place. All measures to increase the circulation of cash should be accompanied by oversight to avoid moral hazard.

Boost the government’s ability to resist militia demands

The Government of National Accord and the CBL, which acts as the Treasury, are in an impossible position, juggling competing demands for money from actors including the armed groups. European governments should consider imposing an external constraint on spending on salaries, especially those of the bloated security sector, to help the CBL and the government push back against these demands, rein in public spending, and resist threats by militias. This could take the form of a budget assistance programme or an international mechanism (such as IMF staff monitoring) to help the CBL and the government manage public spending.

The idea that there is a lot of money for salaries or to be distributed among competing actors will increase demands, sometimes violent, by militias. An external constraint and a shared economic programme with Western assistance would allow the government to say that it does not hold the “keys to the safe”, while prioritising assistance to local councils or agencies dealing with the humanitarian crisis, and achieving “quick wins”. Libya needs a limit on salary expenditure in order to keep up with its current commitments and avoid unreasonable demands, but at the same time it needs more government revenue to restart the economy.

Address the political issues blocking oil production

Restarting oil production is the best way to address Libya’s budget crisis, even though the current low market prices means it will generate only limited cash. This should be used to lessen reliance on the CBL’s reserves, which are depleting fast, not to increase expenditure on salaries. Reopening oil terminals in the east and recommencing production in the south-west will be crucial. On the latter, it is important for the unity government to reconcile with the city of Zintan, which controls oil production in the region and is currently boycotting the Presidential Council. This will require external mediation, both from UNSMIL and drawing on the resources and expertise of the EU Liaison and Planning Cell (EULPC), which brings together military and mediation expertise from the 28 member states.

Build a consensus economic policy

The IMF and the World Bank have previously worked to bring the various Libyan governments to a consensus on the budget. This produced an agreement in Istanbul in 2015 that allowed the CBL to begin to rein in public spending. Now, the EU, in coordination with international financial institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, should help the Presidential Council’s newly formed financial committee to address the economic crisis. While training programmes, such as the one led by the World Bank, can do a lot to increase technical expertise within the bureaucracy, this financial committee will deal primarily with political issues, which will require external mediation to avoid creating new conflicts.

Reconciliation and institutional crisis

Help to push Libyan Political Agreement through the House of Representatives

Approval by the House of Representatives is crucial to give the agreement and the unity government full legitimacy. Numerous attempts to hold a vote on the agreement and on the selection of Government of National Accord ministers have been violently disrupted by a hostile minority, and it is now clear that the only way to have a free and functioning parliament is to hold its meetings outside the area controlled by General Haftar, which includes Tobruk. The EU and its member states should state clearly that international recognition of the House of Representatives is conditional upon its ability to guarantee the freedom of expression of its members and that they welcome (and can support, upon request) the move to any location where this freedom can be guaranteed.

Organise a General Assembly to bring together MPs and mayors

Currently, Libya’s political institutions fail to represent many in the country, particularly local powers. In his 2 March statement before the UN Security Council, Special Envoy Martin Kobler announced his intention to work on the creation of a Grand Shura Council, which would include mayors and tribal leaders. While selecting the tribal component might take longer, Europe should assist UNSMIL in organising a General Assembly of mayors and MPs from both the House of Representatives and the newly created State Council.

This forum could help to close the gaps between the parties, address the humanitarian crisis, and provide an impulse to the political process. It would bring together the MPs with the mayors who have been a major driver of unity and local ceasefires in the past two years. Over time, all municipalities could create the “majlis shura” – advisory bodies including tribal and social leaders, whose legal basis is set out in Law 59 and which are already active in many municipalities. This General Assembly should be a political forum for national dialogue and reconciliation, not a legislative authority to rival the House of Representatives or the State Council.

Help the unity government reconcile with eastern Libya

It is essential for the Government of National Accord to reconcile with the forces dominant in eastern Libya. The EU, in coordination with UNSMIL, can do a lot to help the Presidential Council devise a proposal that brings in the east without disappointing the government’s backers in Tripoli. There is broad support throughout Libya for devolution and decentralisation of power, and this is likely to have a central place in the new constitution.

An important part of the unity government’s powerbase is composed of municipalities, both in the west and south of the country. A broad framework for decentralisation at city council level could bring together all parts of Libya. This would go some way towards appeasing the unity government’s opponents who are currently gathered around General Haftar. Devolved economic institutions should also be part of the picture, particularly alongside a more equitable distribution of oil revenues. The EU should make clear that alongside its commitment to preserve the integrity of Libya, it is ready to support the decentralisation of power.

High-level political pressure

The EU, and member states that are part of the International Support Group and/or the UN Security Council, should keep their diplomatic attention and commitment high. They should aim to ensure that the Government of National Accord works in the regional context towards de-escalation, and that the goals set out at the Rome conference in December, starting with support for the unity government and the non-recognition of rival governments, are implemented by all parties. To this end, the EU and its member states should work on three elements:

Pressure Egypt

Europe should make clear that it takes President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi at his word on his support for Libya’s unity government.10 As part of this, the EU should demonstrate that it will work with the US to enforce the agreement and existing UN Security Council resolutions, even in the face of violations backed by Egypt, whether in terms of arms transfers to forces opposed to the unity government, or support for economic institutions that serve rival governments. This is all the more important given that Egypt supported all relevant UN Security Council decisions on these issues.

Thwart the growth of parallel institutions

Europe should block efforts to establish or consolidate parallel institutions in eastern Libya, in accordance with existing UN Security Council Resolutions. To this end, it is important that the US, the EU, and EU member states continue working with the Presidential Council to monitor attempts to sell oil or to print cash by the parallel “Central Bank” and “National Oil Company” which answer to the rival government in Beyda.

Individual sanctions against those supporting illegal oil or arms deals

The EU already has in place a system to issue sanctions against individuals who obstruct the political process. These have been used against two members of the near-defunct Islamist-leaning “Tripoli government”, and against the House of Representatives speaker, who was placed under a travel ban and an asset freeze. Similar measures should be devised for those individuals who are implicated in illegal attempts to sell oil, dispose of Libyan assets, or deliver weapons in contravention of existing UN resolutions.

Security

Support Military Joint Command

The Presidential Council recently created a military Joint Command to combat ISIS. This is an essential step to ensure Libyan ownership of the process and coherence in military strategy. If correctly structured, it will also help prevent Libyan sub-national actors from profiting from their direct relationships with the US and other countries to avoid striking a power-sharing deal. In other words, it is one of the means to avoid the damaging search for the “Peshmergas of Libya”. The EU and its member states should push other Libyan actors, starting with Haftar’s Libyan National Army, to place themselves under the command of the unity government, which is supreme commander of the armed forces, and to join the Joint Command. The EU member states should also discuss what forms of assistance and advice they could offer to this command, starting with intelligence and communications.

Give an exemption to the arms embargo to fight ISIS

Lifting the arms embargo is problematic, as there is no guarantee that the weapons would not fall into the wrong hands. However, Europe has an interest in ensuring that the unity government can face security threats, particularly from ISIS. European governments should ensure that a centralised procurement system with a degree of international and independent oversight is in place before they even consider approving an exemption to the embargo for the unity government. This is particularly important for those who are members of the UN Security Council, whose Sanctions Committee is tasked with considering exemption requests.

Launch CSDP mission

An EU Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) mission to train Libya’s police, rebuild the judiciary, and reform the security sector is a good idea. The failure of the post-Gaddafi security sector was central to the new outbreak of fighting in 2014: the constellation of militias was the main source of insecurity rather than the origin of stability. The Government of National Accord needs help to rethink the sector and design a model that is as inclusive as possible. While supporting this rethink, the CSDP mission could help to train lightly armed police forces, with an emphasis on investigative capacities and outreach to the population. With help from the CSDP mission, the government could build community security programmes with some degree of popular participation, in coordination with local authorities. Rebuilding the judiciary and reopening courts should be the priority, along with training security details to protect judges, lawyers, and witnesses.

The reform of the security sector should be part of the reconciliation not just between Tripoli and eastern Libya, but also between the central and local governments, and between Libyan Arabs and minorities. European pressure to move too quickly might be used by some groups to override others, leading rapidly to conflict.

Migration and the refugee crisis

Redesign anti-smuggler Operation Sophia

There appears to be a genuine concern among Libyan municipalities and decision-makers about the dangers and the inhumanity of people-smuggling. The EU could redesign Operation Sophia, working with the Government of National Accord, to allow for a greater degree of Libyan and regional ownership. The EU should explore the possibility of joint patrols with the Libyan and Tunisian coast guards, and of coordinating the actions of central government agencies (starting with the Interior Ministry) with those of municipalities.

Increase inspections and oversight to guarantee rights of migrants

The EU should strengthen its own presence and that of the international organisations of which it is part. It and its allies should carry out inspections of detention centres, in coordination with civil society and human rights organisations where possible. European governments should continue to strengthen the presence of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and the UN refugee agency (UNHCR) in the country, while mobilising its agencies to deal with the humanitarian crisis, working with local councils where possible.

Push for ratification of the Geneva Convention

Europe should push Libya’s legislative authorities to ratify the Geneva Convention. This would commit them to ensuring adequate protection for refugees, and would make it possible for Europe to deal with Libya according to international law.

Conclusion

Europeans risk making two errors. The first is to see Libya purely through the lens of counterterrorism, or of the migration “threat”. The second is to take a purely technical approach, focused on building capacity. All these things are important, but to achieve lasting results, the EU and its member states need to help the unity government tackle the economic crisis, step up reconciliation between factions, and develop functioning representative institutions. On top of this, the EU and its member states can pressure their allies in the region to help to avoid Libya falling victim once again to regional dynamics that fuel violence and division rather than stability.

To grapple with these problems, technical solutions and expertise are very important, but high-level political efforts are even more so – and these were precisely the elements that were missing after 2011. Europeans and Libyans cannot afford to miss this second chance.

Notes

1 See, for instance, Eric Schmitt, “Obama Is Pressed to Open Military Front Against ISIS in Libya”, the New York Times, 4 February 2016, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/05/world/africa/isis-libya-us-special-ops.html?_r=0.

2 Where not otherwise indicated, this paper is based on confidential interviews and meetings conducted by the authors with Libyan, European, Arab, and American political and security officials in Brussels and Tunis in April 2016.

3 Rori Donaghy, “Interview: Martin Kobler, the UN envoy trying to put Libya back together”, Middle East Eye, 25 April 2016, available at http://www.middleeasteye.net/news/meet-martin-kobler-un-envoy-trying-put-libya-back-together-again-482900992#sthash.IoiEZ0VT.dpuf.

4 Michael Schaeffer and Wesal Ashur, “Overview: Libya Public Financial Management”, the World Bank, March 2016, hard copy given to the author by the World Bank Libya country office.

5 Saleh Sarrar, Caroline Alexander, and John Follain, “Unexpected Glimmer of Hope Arises in Libya”, Bloomberg, 6 April 2016, available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-06/unknown-and-untested-libyan-leader-makes-inroads-toward-unity.

6 Frontex, annual risk analysis 2013–2015, available at http://frontex.europa.eu/publications/?c=risk-analysis.

7 Mattia Toaldo, “Libya’s migrant-smuggling highway: Lessons for Europe”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 10 November 2015, available at http://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/libyas_migrant_smuggling_highway_lessons_for_europe5002.

8 See, for instance, Nick Gutteridge, “Libya’s rulers ‘weaponise’ migrants threatening to flood Europe with MILLIONS of Muslims”, Express, 3 November 2015, available at http://www.express.co.uk/news/world/616657/European-migrant-crisis-refugees-Libya-government-war.

9 Anthony Dworkin, “Five years on: A new European agenda for North Africa”, European Council on Foreign Relations, 18 February 2016, available at http://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/five_years_on_a_new_european_agenda_for_north_6003.

10 “Egypt’s El-Sisi Shifts His Support To The UN-Backed GNA”, the Libyan Gazette, 7 May 2016, available at https://www.libyangazette.net/2016/05/07/egypts-el-sisi-shifts-his-support-to-the-un-backed-gna/.

About the author

Mattia Toaldo is senior policy fellow for the Middle East and North Africa Programme at the European Council on Foreign Relations and has been studying Libya since 2004.