Iran´s New Way of War in Syria

14 Feb 2017

By Paul Bucala for The Institute for the Study of War (ISW)

This article was external pagepublishedcall_made by the external pageInstitute for the Study of Warcall_made and the external pageCritical Threats Projectcall_made in February 2017.

Executive Summary

Iran is transforming its military to be able to conduct quasi-conventional warfare hundreds of miles from its borders. This capability, which very few states in the world have, will fundamentally alter the strategic calculus and balance of power within the Middle East. It is not a transitory phenomenon. Iranian military leaders have rotated troops from across the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, Artesh, and Basij into Syria in order to expose a significant portion of its force to this kind of operation and warfare. Iran intends to continue along the path of developing a conventional force-projection capability.

Iranian military planners deployed thousands of soldiers from across its military branches over a 15-month operation to set conditions for the envelopment and eventual recapture of Aleppo City by pro-Assad forces in December 2016. They reoriented forces that had traditionally focused on defensive operations into an expeditionary force capable of conducting sustained operations abroad for the first time since the end of the Iran-Iraq War.

These developments signal a larger strategic shift on the part of Iran’s military leadership toward a more aggressive posture in the region. Iran is finding that asymmetric capabilities designed to deter the U.S. or Israel are insufficient to conduct the more conventional military operations required in Syria and elsewhere. The Iranian military is overcoming significant institutional obstacles to meet these new requirements.

The campaign for Aleppo reflects Iran’s success in applying this new approach to waging war. Iranian ground troops boosted the capabilities of Iranian-backed proxies and enabled pro-regime forces to seize and hold key terrain from opposition forces. Iranian forces successfully generated campaign plans, fought alongside local and foreign partners, took heavy casualties, and returned to the front in a sustained rotational pattern. The Iranian military also exposed its next generation of leaders to the fight, positioning them to continue evolving Iranian military doctrine and institutions along this path.

Iran’s continued evolution of its hybrid model of warfare in Syria will strengthen its capacity to project power in the Middle East. The procedures and tactics that Iranian forces have developed in Syria will facilitate Tehran’s efforts to deploy forces alongside similar proxy forces in other theaters, such as Iraq or Lebanon. Allowing Iran to consolidate its influence in Syria enables Tehran to expand and improve the capabilities of its proxies and direct them against U.S. interests and allies if it chooses.

The scope of Iranian combat operations in Syria guarantees that Iran will remain a dominant player on the ground, regardless of any shifts in Russia’s official position on Iranian involvement. Russia has outsourced the ground campaign to Iran and would not be willing to commit the many thousands of Russian troops required to replace Iranian troops or Iranian-backed proxies in the conflict. Most importantly, it signals that Iran’s leaders have decided for the first time in the history of the Islamic Republic to focus on developing a conventional force projection capability that can seriously challenge the armed forces of its neighbors. The balance of power in the region may be forever altered by that decision.

Introduction

Iranian military activities over the last year in Syria mark a significant transformation of Tehran’s approach to conducting operations abroad. Iran reoriented a sizable portion of its armed forces to sustain rotations of combat troops in the campaign to recapture Aleppo city for the Assad regime. Elements of Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) brigades deployed and fought alongside Quds Force-led proxies. Basij units, whose role had previously been exclusively internal, have fought on the front lines in Syria and died by the dozens. Even the Artesh, Iran’s conventional military that has traditionally focused only on defending the country’s borders, has deployed combat forces into the Syria fight. The Iranian military has thus demonstrated the capability to send combat forces hundreds of miles from its borders and sustain them in grueling high-intensity warfare—a capacity shared with only a handful of other states. Tehran is well-positioned to continue its current level of military involvement in Syria, moreover, and could attempt to export its deployment model in other theaters of operation. This “whole-of-military” approach expands Iran’s ability to conduct long-term expeditionary operations and transforms the nature of the Iranian military threat in the region.

Iran expanded its military presence in response to the changing force requirements of the Syrian battlefield. The Critical Threats Project documented the involvement of the IRGC regular ground forces in Syria in its March 2016 report, Iran’s Evolving Way of War: How the IRGC Fights in Syria. Iranian military planners have expanded this deployment model to include contributions from the Artesh, Iran’s regular army, and the Basij Organization, an all-volunteer paramilitary force. The presence of these Iranian ground troops proved critical in setting conditions for the envelopment and the eventual recapture of the city of Aleppo in December 2016.

This report relies on Iranian news outlets and social media to document Iran’s expanded capability to conduct military operations in support of the Syrian regime. U.S. allies and interests in the Middle East face a significantly heightened Iranian threat as Tehran becomes increasingly willing and able to project power abroad. Iran’s capacity to generate and sustain expeditionary operations is inherently limited by its ability to move personnel and resources back and forth from Iran freely, however. As the new U.S. administration reconsiders policy options toward Iran, policy-makers and analysts should redouble their efforts to target and impose fresh sanctions on the individuals and entities involved in the network that facilitates this transportation in order to constrain Iran’s destabilizing efforts in Syria and across the region.

Iran’s Surge for the Assad Regime

Iran has reshaped its military activities in Syria over the course of the civil war. Changes on the Syrian battlefield have driven Iran to intensify its military activities in the country, culminating in Iran’s surge of ground forces in support of the campaign to recapture the city of Aleppo. The increased involvement of Iranian troops on the Syrian battlefield in October 2015 marked a significant escalation of Iran’s approach to the Syrian conflict and introduced capabilities that turned the tide of the fighting.

Iran has provided military assistance in support of the Assad regime since the early days of the Syrian Civil War, although its efforts were relatively limited during the first stages of the conflict. Tehran sent limited numbers of Iranian military officers predominantly from the IRGC’s elite expeditionary wing, the Quds Force, to provide technical and top-level support to Syrian forces. These officers also formed local paramilitary groups and supported the deployments of Iraqi Shia militias and Hezbollah forces to Syria. But the limited manpower and capabilities of the Quds Force proved insufficient to enable the ground operations required by Iranian military planners. Iran also deployed retired and active high-ranking IRGC Ground Forces personnel to provide top-level advisory support to the Syrian regime, but that effort, too, was inadequate to the task at hand.

Iran escalated its involvement in Syria in the latter half of 2014, as Assad faced increasing losses on the battlefield. The emergence of ISIS in Iraq also required the reallocation of Iraqi-Shia militias that had been fighting in Syria back to Iraq to defend Baghdad, depriving Iran of a critical manpower pool. Quds Force officers mobilized thousands of foreign Shia fighters, including Afghans, to mitigate the attrition of the Syrian regime’s forces. Losses of mid-ranking Iranian officers during this period indicate that the Iranian military assumed command of field operations in some locations. Iran’s military involvement at this level failed to reverse the tide of the civil war, however, and the Assad regime suffered considerable casualties and territorial losses over the first half of 2015.

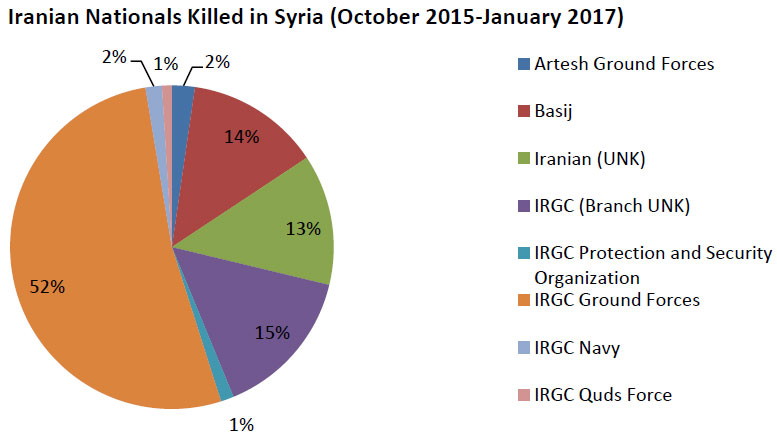

The Iranian regime surged deployments to Syria after September 2015 and over the course of 2016 to participate in the operation to encircle and recapture the city of Aleppo. These force contributions were predominantly comprised of IRGC Ground Forces, although they also included contributions from the Quds Force, Iran’s conventional military known as the Artesh, and the Basij paramilitary organization. The chart below illustrates the composition of the 306 casualties taken by Iranian forces from October 2015 to January 2017. Reports place the majority of these casualties around the city of Aleppo, although a handful of Iranian casualties have also been reported in Hama Governorate, near Palmyra, and around Damascus during this time period.

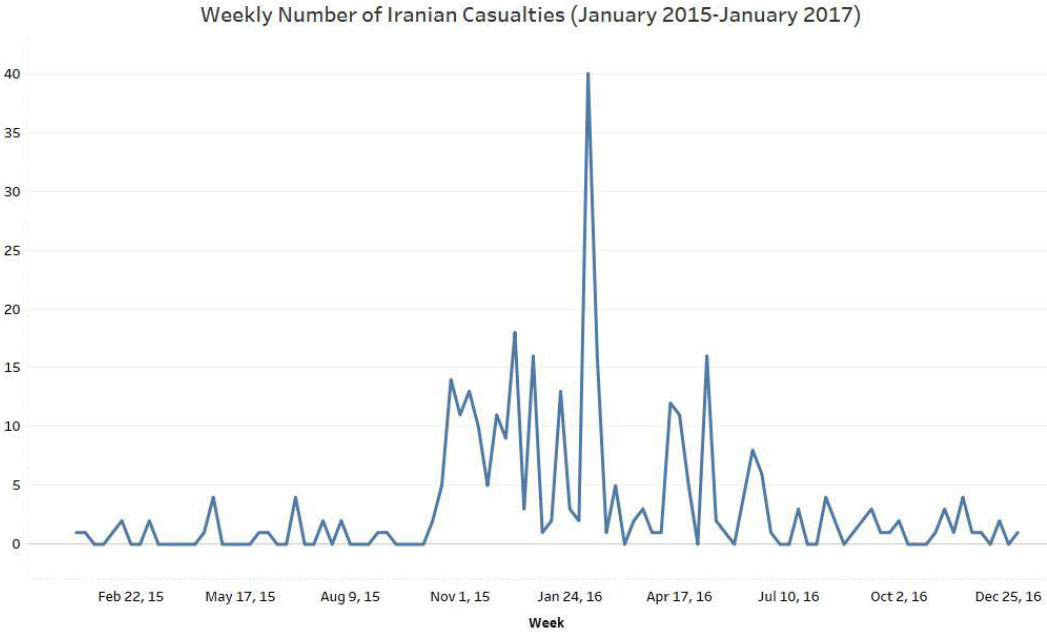

Larger numbers of Iranian troops were accompanied by a much more effective but risky deployment model that involved the direct participation of Iranian troops on the frontlines. Upticks of reported Iranian casualties closely follow waves of both pro-regime and opposition offensives around the city of Aleppo, reflecting the decision by Iranian planners to forward-deploy troops. The graph below documents reports of Iranian casualties over a two-year period from January 2015 to January 2017.

Iranian soldiers participated heavily in the pro-regime offensives across the southern front of Aleppo from October 2015 to January 2016, along with Lebanese Hezbollah Forces, Iraqi Shia fighters, and Afghans and Pakistanis trained in Iran. Iranian ground troops played a critical role in operations to relieve the besieged towns of al Zahra and Nubl in February that also severed a major opposition supply line into Aleppo City from Turkey. Iran lost more than 50 troops during the first half of February, the majority of which were likely involved in this operation. Iranian forces appear to have gone through a reconstitution phase in March 2016, although at least one Iranian officer was also lost during the Syrian regime’s operation to recapture the city of Palmyra.

Iranian forces participated in efforts to repel opposition offensives along the southern front of Aleppo from April to June 2016, including around the towns of al Eis, Zitan, and Khan Touman, where the IRGC Ground Forces’ 25th Karbala Division suffered 13 killed and 21 wounded during a rebel attack on May 6. Iranian casualties spiked again in June during opposition offensives southwest of Aleppo. Iran took casualties in July when pro-regime forces launched an offensive to sever the main supply route into Aleppo and again in the first week of August, when opposition forces staged a campaign to break the siege.

The Aleppo operation underscores the Syrian regime’s reliance on Iranian forces to direct and supply the manpower for effective pro-regime offensives on the ground. Russian airpower by itself cannot explain the successful operation to recapture Aleppo. The Syrian regime’s earlier use of area bombardment to suppress opposition defenses did not preclude rebels from repelling regime offensives in 2014 and 2015. Moreover, the fact that Iranian and proxy troops took significant casualties indicates that the Russian air campaign alone could not bomb rebel forces into submission.

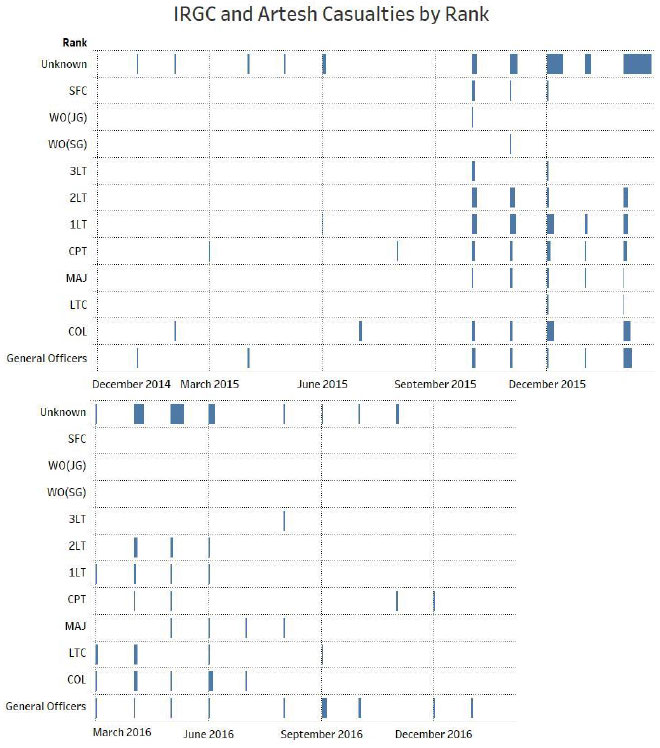

The presence of Iranian soldiers on the ground helps explain how various linguistically-diverse proxy forces managed to launch coordinated and simultaneous offensive operations against committed and relatively well-armed rebel forces. Iranian military planners appear to have used IRGC officers to reinforce and serve as command elements for proxy forces, as hypothesized in the Critical Threats Project’s 2016 report on the IRGC Ground Forces in Syria. This deployment model explains the distribution of ranks of IRGC officials killed in Syria, which contain a disproportionately high number of junior, mid-level, and senior IRGC officers. These officer cadres were not commanding their own enlisted soldiers in Syria—who do not appear to show up on the casualty rolls--but rather served as an integrating element among Iran’s diverse set of proxies operating on the ground in Syria.

The graph below displays the distribution of ranks by month for IRGC and Artesh casualties. The chart is weighted so that larger segments represent more casualties taken at that rank for a given month.

This deployment pattern is the most cost-effective model for Iranian military planners. It minimizes the potential number of Iranian losses while also improving the combat effectiveness of local partners. It also positioned Iranian troops and proxy forces to play a direct role in supplying intelligence for Russian air strikes, as one IRGC major general disclosed during a news interview. Lebanese Hezbollah likely supported this effort with assistance from Russian Special Forces. Iranian military planners also deployed specially-trained Iranian volunteer fighters and elite Special Force teams to the front lines in order to provide combat support for the numerous but relatively poorly-trained proxy militias.

Iranian forces adopted a new deployment model after August 2016 as pro-regime operations tightened the encirclement of Aleppo. The increasing urban and risky nature of the battle around Aleppo--coupled with the May 2016 defeat at Khan Touman-- probably drove Iranian military planners to pull back forward deployed troops. The IRGC lost a disproportionately high number of general officers--more than a quarter--after August 2016 as a percentage of all reported losses. This data point indicates that the Iranian military maintained its top-level command and control structure over its proxy forces until the eventual recapture of Aleppo by pro-regime forces in December 2016 even as it pulled its cadres away from front line fighting.

The 15-month Aleppo operation proved to Iran’s senior leadership the success of its new approach of waging war abroad. Iranian officers did not shy away from celebrating their accomplishment. IRGC Major General Yahya Rahim Safavi, the Supreme Leader’s senior military advisor, credited “the Iran-Russia-Syria-Hezbollah coalition” for “liberating” Aleppo. Iranian forces successfully exercised the ability to design operational plans, fight a determined enemy alongside local and foreign partners, take casualties, and return to the battlefield. The Aleppo campaign also exposed a large portion of Iran’s operational units and junior officers to participating in a sustained operation abroad, better positioning these forces to wage similar campaigns in the future.

1) Dec 2015: IRGC officer from 2nd Imam Mojtaba Brigade boasts about soldiers from his unit involved in clearing operations around Zitan and Khan Touman. Six members of 2nd Imam Mojtaba brigade reported killed in December.

2) Jan 2016: Basij Special Forces conduct operation near Khan Touman and suffer heavy casualties.

3) Feb 2016: IRGC and Basij Special Forces conduct operation to relieve the siege of Nubl and al Zahra under the cover of the Russian Air Force. More than 40 Iranian casualties occur during the first half of February, the majority of which likely participated in the operation.

4) Apr 2016: IRGC forces suffer casualties in vicinity of al Eis during offensive conducted by rebel groups.

5) Apr 2016: Fars news Agency published picture of Artesh Special Forces in the town of al Hadher.

6) Apr 2016: Pro-regime sources report that Artesh Special Forces conduct operation with Lebanese Hezbollah and Iraqi Shia militias against opposition forces in the town of al Eis.

7) May 2016: IRGC forces suffer more than 15 killed when rebel offensive storms Khan Touman.

8) Aug 2016: Iranian forces take casualties as rebel forces launch offensive to retake siege of Aleppo.

9) Oct 2016: A Basiji is reported to be killed in 3000 apartments Protect amid rebel counteroffensive. Multiple other Iranian casualties reported.

10) Nov 2016: Iranian casualties spiked as pro-regime forces seize key districts in southwestern part of city.

Iran’s “Whole of Military” Approach to Syria

Iran has strengthened its force projection ability in accordance with the operational demands of the campaign around Aleppo. In doing so, Iranian military planners have demonstrated their determination and willingness to overcome doctrinal and institutional obstacles within Iran’s military structure. The Iranian military’s proven ability to integrate troops from across its branches into foreign operations indicates that Iran’s capability to project force abroad is far greater than what is commonly assessed.

IRGC Ground Forces

The Iranian regime relied heavily on elements from IRGC Ground Forces units to participate in pro-regime operations around Aleppo, marking a significant transformation in the organization’s doctrine and historic posture. IRGC Ground Force units have been oriented toward a defensive mission of protecting the Iranian regime from external and domestic threats since the end of the Iran-Iraq War. The 2008 reforms of the IRGC Ground Forces were aimed at decentralizing the organization’s structure and hardening units’ ability to survive an attack from the U.S. or Israel, although decentralizing their command-and control theoretically made them less effective as a conventional military force.

The Iranian regime transformed the role of IRGC Ground Forces in Syria following the Russian intervention in September 2015. High-ranking IRGC Ground Forces officers served as senior advisors in Iran’s military involvement in Syria since at least the middle of 2012, but their involvement was limited to a senior Train, Advise, and Assist (TAA) capacity. Casualties among IRGC Ground Forces personnel escalated significantly after September 2015, corresponding with reports that Iran had increased its number of troops in the country. The high casualty tolls after this period reflect Iranian military leaders’ decision to deploy greater numbers of IRGC Ground Forces to the frontlines in a new deployment model.

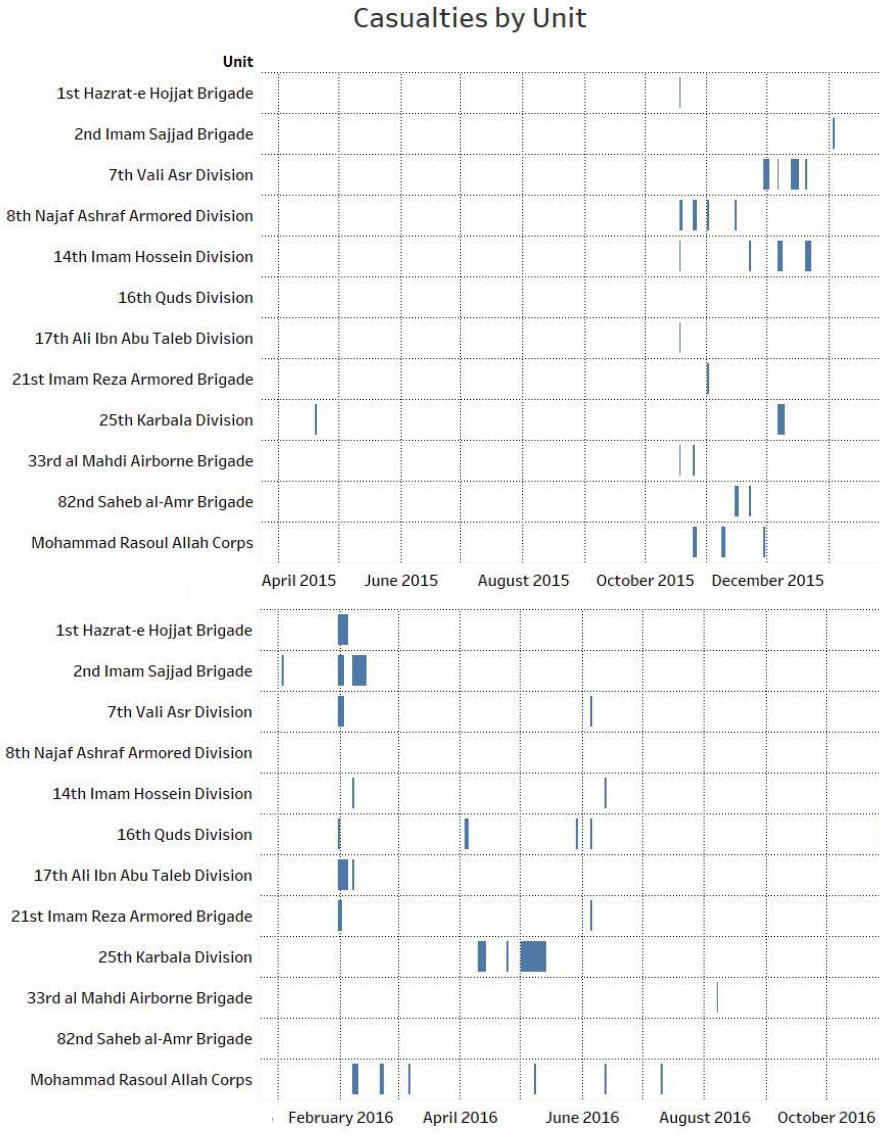

The distribution of casualties indicates that specific elements from IRGC Ground Forces units were deploying and taking casualties on the frontlines in Syria after September 2015, as the Critical Threats Project has previously documented. Iranian military planners appear to have cycled through IRGC Ground Forces units, likely in an effort to expose as many different units as possible to the conflict in Syria while also ensuring that fresh rotations of troops were available. Units tapped repeatedly to deploy were likely the best equipped and trained units within the IRGC Ground Forces’ order of battle. The large number of IRGC Ground Force units selected to contribute to the conflict in Syria indicates a broader transformation in the organization’s fundamental posture, rather than an effort to develop a small elite capability.

The elements of deployed IRGC Ground Force appear to have operated at different levels of the battlefield in accordance with operational needs. Whereas the mid-level and high-ranks of some casualties is indicative of a top-level advisory model, several IRGC Ground Force elements appear to have served as combat elements on the ground. The 2nd Imam Mojtaba Brigade of the 7th Vali Asr Division and the 2nd Imam Sajjad Brigade took relatively lower-ranked casualties, for example. Casualties identified as belonging to the IRGC Ground Forces Special Forces units known as the Saberin also appear to contain lower-ranked casualties.

Data points in Iranian press reports indicate that IRGC Ground Force personnel deploy on two-three-month rotations in Syria. The graph below of reported casualties by IRGC Ground Force unit supports this conclusion. The graph is weighted with larger segments for weeks when a specific unit suffered more than one casualty. Clear groupings of casualties are evident from the 8th Najaf Ashraf Division, 25th Karbala Division, 7th Vali Asr Division, and 2nd Imam Sajjad Brigade, Mohammad Rasoul Allah Corps, and others, indicating that elements from those units deployed in a cyclical pattern to the frontlines. This graph does not display those units which took too few casualties to assess a rotational pattern or IRGC Ground Force casualties not identified as belonging to a specific unit. The changing nature of Iran’s deployment pattern is also indicated in the graphic, as Iran appeared to pull-back its forward deployed troops after June 2016 once the fight in Aleppo became more urban and risky for Iranian troops.

The campaign in Syria is transforming the IRGC Ground Forces, an organization structured for defending the regime against ground invasion and domestic unrest. Whereas the IRGC Ground Forces once trained for asymmetric warfare against a foreign aggressor, the IRGC Ground Forces launched an exercise in western Iran “based on actual operations in Syria” in late January 2017. Experiences in Syria could have also contributed to the IRGC leadership’s decision to form a dedicated IRGC Ground Forces’ air assault unit (helicopter-borne infantry), “required for supporting and even conducting offensive operations considering the type of missions carried out by the [IRGC] Ground Forces across the world,” according to Iranian news outlets. It will be important for analysts to monitor further changes, particularly in the IRGC Ground Forces’ order of battle and acquisition efforts, in order to assess the extent of the Syrian conflict’s effect on the IRGC’s decision-making.

The Artesh

The involvement of Iran’s regular military, the Artesh, in Syria is comparatively much more limited than the IRGC’s, but indicates a significant flexibility by Iranian military planners to overcome doctrinal limitations in response to changing force requirements. The Artesh’s mission has historically been constrained to protecting Iran’s territorial integrity, and there were no confirmed deployments of Artesh troops to a combat zone between the end of the Iran-Iraq War in 1988 and 2016. The decision to deploy Artesh troops to Syria therefore marks a fundamental shift in Artesh doctrine and its status within the IRGC-dominated military establishment.

Iranian military planners deployed at least two packages of Artesh Special Forces and regular troops to Syria. The first took losses in April 2016 and appears to have been aimed at reinforcing IRGC Ground Forces south of Aleppo. All casualties from this deployment were reported to have been members of the Artesh Special Forces. The commander of the Artesh Special Forces unit that appears to have spearheaded this deployment was later promoted twice in quick succession, presumably signaling the Iranian regime’s satisfaction with the Artesh Special Forces involvement in Syria. A single Artesh casualty reported on August 1, who was “at the end of his 45-day deployment,” suggests that there was a separate Artesh deployment in June 2016, moreover. The soldier hailed from a non-special forces Artesh unit, indicating that conventional Artesh units are also deployed to Syria at least in part. The full extent of the Artesh’s involvement in Syria is unknown, but it likely is far broader than these two deployments. Transport planes owned by the Artesh Air Force regularly operate in Syria, for example.

Artesh troops appear to be integrated within the IRGC’s command and control structure in Syria, as Artesh Commander Major General Ataollah Salehi disclosed in an interview in April 2016. This data point reveals a willingness and ability to manage the long-standing friction between the two organizations. In June and July of 2016, the Iranian military sought to boost the interoperability of the two services through a series of reforms to Iran’s command structure that will better enable it to plan and conduct military operations using all branches of Iran’s conventional forces. Better integrating the Artesh into Iran’s armed forces -- while also subordinating it the IRGC--strengthens Iran’s force-projection capabilities in the face of rising force commitments overseas.

The Syrian conflict has laid the groundwork for further changes within Iran’s regular military. Comments from Artesh officials signal a broader evolution in Artesh doctrine to include preemptive deployments abroad as part of the organization’s mission to protect Iran’s borders, for example. The Artesh might also be prioritizing the development of capabilities that would better enable it to wage operations beyond Iran’s borders. The formation of Artesh quick-reaction units earlier in 2016 and their subsequent deployment to the Mohammad Rasoul Allah Drills in southeastern Iran, for example, reflect the Artesh’s commitment to developing its rapid force projection capabilities. Rhetoric from Artesh officers indicate that they welcome a broader mission set, likely in a bid for increased funding and prestige for an organization once regarded with suspicion by the regime’s leadership.

The Basij

Iran’s military planners have repurposed some Basij elements into a fire-support force for IRGC elements operating in Syria. This development constitutes a significant evolution for the Basij, an auxiliary force tasked with internal security, morals policing, and serving as a mobilization base for the IRGC Ground Forces in the face of external or domestic threats. A total of 87 Basij fighters and other Iranian “volunteers” appear on the casualty rolls from October 2015 to January 2017.

The Iranian military used Basij Special Forces units known as Fatehin to train and absorb volunteers from across Iran’s provinces. The history of the Fatehin units is not clear, but one Fatehin unit commander claims that these elite Basij Special Forces units were created in the early 2000s. Another report suggests that IRGC Brigadier General Hossein Hamedani played a key role in organizing them to deploy to Syria.

These fighters were engaged in direct combat. Young Basij volunteers have very little to offer in terms of training or advising but can provide dependable firepower to other Iranian troops on the ground. According to comments from Iranian commanders, Fatehin Special Forces played a direct role in supporting pro-regime operations south of Aleppo in January 2016 and again to recapture the towns of al Zahra and Nubl in February 2016. The commander of Tehran’s Fatehin unit indicated that Fatehin forces fought as a cohesive unit near the town of Khan Touman southwest of Aleppo in January 2016, when they suffered 12 casualties out of more than 250 fighters operating on the ground. Thirty Fatehin soldiers were killed in Syria as of October 2016, according to this Fatehin commander.

Iranian military officials have voiced their intention to expand the military effectiveness of the Basij, as signaled by the appointment of Hossein Gheibparvar, a seasoned IRGC Ground Forces brigadier general with experience in Syria, to head the Basij Organization in late 2016. IRGC Commander Major General Mohammad Ali Jafari announced Iran will expand the creation of the Fatehin units, underscoring the regime’s intention to further operationalize the Basij forces into a supporting element for the IRGC’s expanded missions abroad.

The institutionalized involvement of the IRGC, Artesh, and Basij military forces in Syria reflect Iran’s ability to repurpose its armed forces to project power in a relatively conventional manner. It is also a possible indicator of further changes to Iran’s armed forces as the military appears to move away from asymmetric capabilities toward a preference to field conventional military force. Future promotions of more officers involved in Iran’s ground operations in Syria -- rather than officers with backgrounds in intelligence or domestic security -- could signal a concerted effort by the Iranian regime to strengthen its conventional force posture.

The View from Tehran

Iran’s decision to escalate along conventional lines in Syria helps secure Tehran’s strategic goals in Syria. Iran’s military capabilities are insufficient to recapture the entirety of Syria or defeat ISIS decisively in battle, but Tehran’s core interest in Syria is far broader than the anti-ISIS campaign. Iran ultimately seeks to ensure that Iranian proxies can use Syrian territory as a vehicle to project influence into the Levant and maintain a deterrence infrastructure against Israel. The deployment of regular Iranian ground troops improves Tehran’s ability to independently capture and hold territory critical to ensuring that Assad remains in power for as long as possible. It also guarantees Iran the capability to secure terrain strategically valuable to Iran’s power-projection efforts independent of the Syrian central government or foreign actors.

The logic of Iran’s military intervention will drive regime elites in Iran to continue expanding its military presence in Syria. The Iranian leadership almost certainly does not want to expend hundreds of troops in Syria, particularly as it faces widening force commitments elsewhere. The Iranian regime faces no other viable options for achieving its goals in Syria, however. The Syrian regime lacks the capability to plan and conduct successful military operations without Iranian assistance, whereas ceding complete military control to the Russians would inevitably lead to Iran losing strategic leverage in the country.

Iran is well positioned to continue its military involvement in accordance with its strategic goals. The Iranian military appears to be in a state of reconstituting its operations in Syria during the Turkey-Russian-backed ceasefire, although it remains unclear whether Iran intends to commit its forces again to fight on the frontlines. It is clear, however, that domestic factors do not overly restrain Iran’s capacity to deploy force abroad. Iran’s major political factions largely appear to support Iran’s military activity in Syria, as indicated by the lack of debate over Iran’s role in Syria during the otherwise contentious parliamentary and Assembly of Expert elections in February 2016. Improving economic conditions in Iran will ensure that the Iranian regime can sustain the logistics tail needed to support its military footprint in the country.

Iran’s ability to conduct long-term force deployments in Syria is primarily dependent on the presence of forces receptive to Iranian direction and which Iran can reinforce with ground troops. But the Iranian regime’s extensive posture and influence among paramilitary groups in Syria indicate that Iran will maintain this infrastructure regardless of who is in power in Damascus. Recent developments in the region could allow Iranian officials to commit more proxy forces to the fight in Syria, moreover. The successful liberation of Mosul may free up Iraqi Shia fighters for the fight in Syria, while the recent political victories of Hezbollah allies in Lebanon might make Iranian officials more risk-tolerant in directing Hezbollah’s deployments to Syria.

Iran’s continued development of its hybrid model of warfare in Syria will strengthen its capacity to interoperate with its network of proxies in the region. The Iranian military appears to view Syria as a laboratory in order to further shape its evolving way of war, as signaled by the decision to deploy personnel from the IRGC’s advanced officer school to the conflict. The operating procedures that Iranian forces have generated and learned in Syria could allow Tehran to replicate its model of irregular hybrid warfare with similar proxy forces in other theaters, such as Iraq.

Conclusion

The characteristics of Iran’s military activities in support of the campaign to recapture Aleppo should be a wake-up call that Iran has developed a significant capability to generate and sustain military operations abroad. Iranian military planners successfully managed to repurpose a significant portion of its armed forces to operate as an expeditionary force abroad in the first time since the end of the Iran-Iraq War—and many hundreds of miles beyond what they attempted during that conflict. It is a capability that Iran could replicate elsewhere in the region with potentially game-changing implications for the battlefield.

U.S. policy-makers must avoid the temptation to believe that Iranian influence in Syria will be contained within Syria’s borders. The Iranian regime recognizes its proxies in Syria as part of its Axis of Resistance coalition on which Iran can rely to contain the U.S. and its regional allies. An opportunity for Iran to consolidate its influence in Syria translates into an expanded capability to use Syrian territory as a staging point to conduct operations throughout the region to the ultimate detriment of U.S. interests and allies in the Middle East.

The character of Iran’s deployment model complicates policy options to roll back Iranian influence on the battlefield in Syria. Efforts to contain Iranian troops could be hampered by the extent to which these actors are integrated within local and foreign fighter units. Targeting formations of proxies with conventional weapons also risks unintentional escalation with Iran, given the likelihood that Iranian troops are intermingled among the proxy forces.

Iran’s broadening military footprint in Syria exposes Iran to pressure on its ability to move resources into the country, however. The sustained force rotations documented above require a large military supply chain susceptible to the imposition of sanctions or interdiction of air operations. This network is particularly vulnerable as it largely rests on Iran’s ability to conduct aerial resupply through an airbridge that stretches from Iran to Syria. The nuclear deal clearly allows the imposition of U.S. sanctions on Iranian entities and organizations involved in terrorism-related activities, “facilitating a significant transaction” for the IRGC, human-rights violations, and others. U.S. policymakers should leverage these exemptions to apply pressure on the military-industrial complex that supports Iran’s destabilizing efforts abroad.

U.S. policy-makers must recognize that any strategy that emboldens the Russian posture in Syria will not contain Iranian influence in the country. The convergence of Russo-Iranian interests across the broader Middle East indicates that any U.S. appeasement effort to persuade Russia to abandon Iran in Syria will ultimately be unsuccessful. Iran’s role in Syria is costly, and Russia’s leadership would ultimately prefer to outsource the ground campaign to Iran rather than committing the many thousands of Russian troops required to replace Iran in the conflict. Even if a U.S. diplomatic effort overcomes these odds and is successful at affecting a change in Russian policy toward Iran, Iran’s far-reaching influence over Syria’s economic, military, and political institutions ensures that any U.S. effort to subvert Iran’s posture in Syria through Russia will undoubtedly end in failure.

About the Author

Paul Bucala is an Iran analyst at the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. He coauthored ‘Iran’s Evolving Way of War: How the IRGC Fights in Syria’ with Frederick W. Kagan and ‘Iran’s Airbridge to Syria’. His work at the Critical Threats Project focuses on Iranian military operations in Syria and elsewhere. He also coauthored ‘The Taliban Resurgent: Threats to Afghanistan’s Security’ at the Institute for the Study of War.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.