The Arab War(s) on Terror

10 Jul 2014

By Patryk Pawlak, Florence Gaub for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This Issue Brief was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 27 June 2014. Republished with permission.

With jihadi groups in control of swathes of Iraq, deadly attacks occurring on a weekly basis across the region, and governments adopting harsher measures to counter the spiral of violence, terror- ism is back on the Arab agenda. Three years after the killing of Osama bin Laden, terrorist groups – some affiliated with al-Qaeda, some not – are making inroads following a decade of relative containment. And while the region is no stranger to terrorism, Arab states now seem more deter- mined than ever to stamp out the phenomenon.

The return of al-Qaeda…

Although it is true that al-Qaeda suffered serious setbacks in the decade following 9/11 – in particular the killing of Osama bin Laden and several other top leaders – it has managed to regroup and establish strong regional franchises. Indeed, the majority of terrorist attacks are now perpetrated by al-Qaeda’s regional outlets rather than al-Qaeda central.

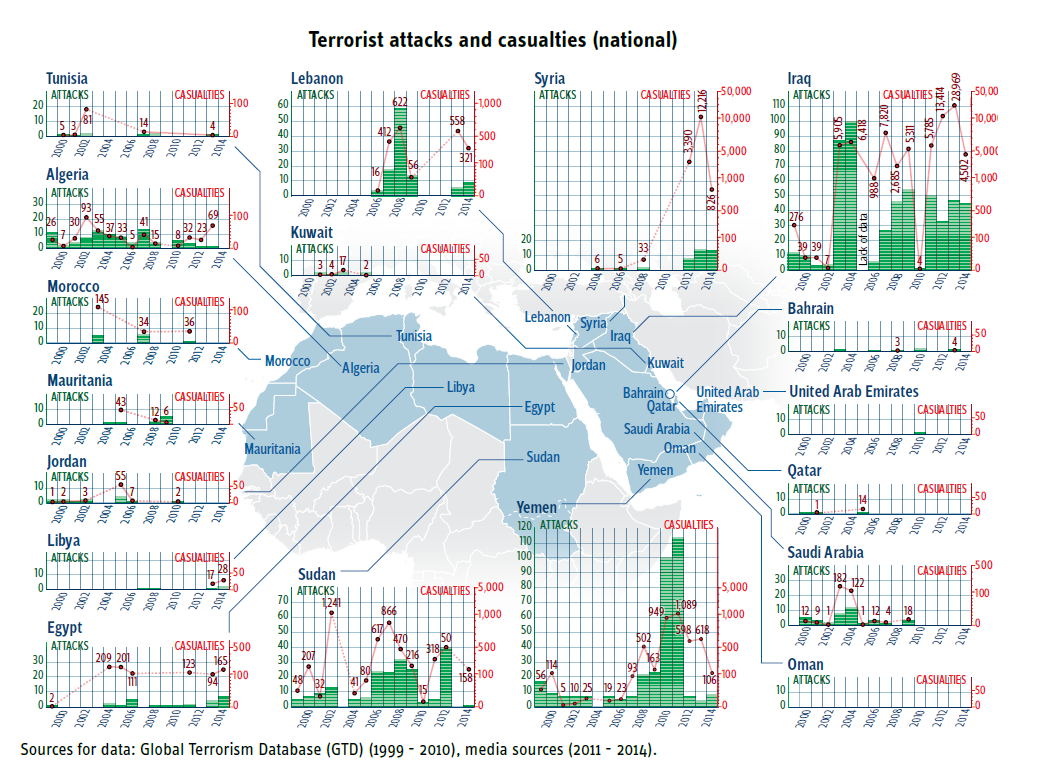

Although al-Qaeda in Iraq was severely weakened during the 2007 US military surge, it has regained strength since the withdrawal of American forces. Originally linked to Jabhat al-Nusra, an al-Qaeda affiliate participating in the fighting in Syria, the group fell out with the central leadership over questions of hierarchy. Now, having dissociated itself from al-Qaeda proper since February 2014 and calling itself the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or ISIS), the group has embarked on a full-scale guerrilla war against the governments of Iraq and Syria. Further south, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) is mainly active in Yemen, where it is currently engaged in a bloody conflict with the Yemeni security forces. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) emerged from the remnants of the Algerian Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat in 2007 and has since conducted numerous terrorist operations aimed primarily at Algerian and European targets.

Al-Qaeda has thus become a more regional organisation than it was before, harnessing local and national grievances to further its own agenda. In Iraq, for instance, ISIS plays on Sunni dissatisfaction following the establishment of a political system from which they feel disenfranchised. In Egypt, al-Qaeda called for war against the Egyptian military after the ousting of President Morsi, while Jabhat al-Nusra has managed to use the chaos of the Syrian civil war to its own ad- vantage.

…and friends

In addition to al-Qaeda, other terrorist groups have also grown in strength, especially in areas where weakened states are unable to control or contain them. A case in point is Egypt’s Sinai, where various home-grown Egyptian groups – such as Ansar Bait al-Maqdis, Jama’at al-Tawhid, and armed Bedouins disgruntled with the govern- ment – have joined forces. Although this development preceded the events of 2011 (tourists were already targeted several times between 2004 and 2006), attacks have since intensified. Similarly, groups like Ansar al-Sharia are taking advantage of the implosion of Libya’s security structure to con- duct operations, particularly in the eastern parts of the country. Adding to regional worries, the branches of Ansar al-Sharia in Libya and Tunisia also recently announced their unification.

For two reasons, terrorism in the Arab world is, by default, a regional and not a national problem. Borders in the region are notoriously porous due to geographical constraints: the desert landscape of the Sahel zone as well as the Arab peninsula is difficult to patrol (in 2003, Saudi Arabia resorted to building a concrete barrier along its border with Yemen). In addition, the limited capacity of most countries in the region to control their own borders facilitates the movement of terrorist groups and supplies. Accordingly, local or national terrorist networks operate regionally be- cause they have the freedom to do so. The border area between Syria and Iraq has been practically unguarded since the US-led invasion, resulting in a ‘jihadi highway’ running in both directions. Lebanon’s border with Syria is just as open, al- lowing Hizbullah fighters and equipment to cross unimpeded. This matters, as Syria’s civil war has taken on a regional dimension precisely because its borders are open to fighters from abroad.

The weapons surplus in Libya has turned the country into a lucrative market for all groups across the region (Egyptian networks in the Sinai recently shot down a military helicopter with surface-to- air missiles most likely obtained in Libya). North African states therefore view the disintegration of Libya’s security apparatus with great concern. Egypt, for example, has repeatedly called for an international conference regarding Libya’s borders to be held later this year. Generally speaking, Arab states are seeking more international cooperation in the War on Terror, and it is in this spirit that Iraq organised the first international Conference on Combating Terrorism in March this year.

Re-defining terrorism: legal measures

Arab states are being called upon to address the current threats; as US President Obama declared this week, it is their job to stop the slide into in- security. In any case, terrorism is not a new phenomenon in the Arab world, and the region has already seen off waves of sustained attacks in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1990s. In 1998, the Arab League adopted the Arab Convention for the Suppression of Terrorism, which defined terrorism as ‘any act or threat of violence, whatever its motives or purposes, that occurs in the advancement of an individual or collective criminal agenda and seeking to sow panic among people, causing fear by harming them, or placing their lives, liberty or security in danger, or seeking to cause damage to the environment or to public or private installations or property or to occupying or seizing them, or seeking to jeopardise a national resource.’

Following 9/11, however, Arab regimes stalled at- tempts to establish an international definition of terrorism at a UN level, worrying that it might be conflated with the legitimate right to resist occupation.

Now, however, several Arab states have (re)de- fined terrorism in even more sweeping ways. In April, Jordan issued a new law introducing harsher sentences for terrorism – broadly defined as ‘any act meant to create sedition, harm property or jeopardise international relations, or to use the internet or media outlets to promote terrorist thinking’ – which include ten year’s incarceration or the death penalty. Egypt’s newly elected President al-Sisi has made the fight against terrorism his number one priority, and a draft law is currently being reviewed which defines terror- ism as actions which may: ‘obstruct’ the work of public officials, universities, mosques, embassies, or international institutions, qualify as ‘intimidation’, ‘harm national unity’, prevent the application of the country’s constitution and laws, or ‘damage the economy’. In June, the Egyptian government also announced a new system of mass surveillance of social media to combat terrorism.

In Iraq, the relevant law states that anyone ‘who instigated, planned or financed, or enabled terrorists groups […] shall be punishable by death.’ Saudi Arabia’s 2013 terrorism law vaguely defines it as ‘any act harming the reputation or standing of the state, or attempting to coerce authorities into doing or refraining from doing something.’ In a similar vein, Algeria toughened its terrorism law last year. Against the current trend, Tunisia is currently reviewing its 2003 law (which defined terrorism as acts which could ‘disturb the public order’ and ‘bring harm to persons or property’) in order to bring it into line with international human rights standards.

Creating more enemies?

Where terrorism is defined in too broad a manner, it is often hard to distinguish between legitimate political opposition and terrorism.

The Syrian regime frames its crackdown on a popular uprising as a fight against Islamist terrorism, while in Egypt, several journalists working for Al Jazeera have been sentenced to lengthy prison terms for having assisted the Muslim Brotherhood. The official branding of the Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation by Syria, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates – 86 years after its founding – seems questionable given the group’s renunciation of violence in the 1970s. And although the Brotherhood stands accused of being involved in the recent terrorist attacks which have struck Egypt (a charge it de-nies), the Egyptian government has, so far, failed to produce any evidence in support of its claims.

Several countries have also taken decisive steps to deal with returning fighters from Syria. According to the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation, up to 11,000 individuals from 74 nations have taken up arms as opposition fighters in Syria. Some countries simply question, and then either release or monitor, the suspected individuals. Saudi Arabia, Morocco and Jordan, how- ever, threaten returning fighters with jail terms.

It remains to be seen to what extent these new laws will curtail freedom of expression or be used to clamp down on citizens expressing discontent through either public protest or social media. But governments should be wary of the limits of repressive techniques: the abuse of new laws to fight political opponents rather than genuine terrorists, combined with pervasive corruption and continued human rights violations, may have negative consequences for domestic and regional stability. The barring of the Algerian Islamic Salvation Front from politics in 1992, for example, undoubtedly contributed to the group’s radicalisation.

Across the board, Arab citizens support measures against terrorism: according to a Pew survey, public support for al-Qaeda has decreased to 17%, while 66% of those questioned expressed concern over Islamic extremism. However, support for Hamas (which Egypt declared a terrorist organisation in 2014) and Hizbullah (declared a terrorist organisation by the Gulf states in 2013) remains steady at 46% and 33%, respectively.

Upping the ante: logistical measures

Arab states have also taken practical steps to curb terrorist activity. Egypt has deployed several battalions in the Sinai, and Tunisia (increasing its troop deployment rates eight-fold) has ordered the aerial bombardment of terrorist training camps on its soil. Algeria, struck by a major attack on an oil installation in early 2013, has reshuffled its internal security directorate, dismissed high-ranking officers in charge of the dossier, and sent some 5,000 troops to patrol its border with Libya. Algeria also joined forces back in 2010 with Mali, Mauritania and Niger to create a joint military committee to combat AQIM.

Despite difficult financial conditions, the budgets of both internal and external security forces have soared across the region. Most of these additional resources will fund new positions (8,700 new posts were created in Tunisia), or salary increases and other perks for existing staff.

Nevertheless, the situation of Arab security personnel remains dire. Underpaid and over- stretched, domestic security forces are also often under-equipped or employed to monitor po- litical opponents rather than terrorist networks. Security forces in Tunis recently went on strike in protest against their lack of equipment, and in Iraq, the intelligence services – crippled af- ter Prime Minister Maliki dismissed personnel trained by US instructors – were almost blind to the developments leading up to the current crisis.

Tough choices?

The knock-on effects of terrorism in the Arab world are being felt across the Mediterranean: EU and Arab League officials agreed at the third ministerial meeting in June 2014 ‘to share, as appropriate, assessments and best practices, as well as to cooperate in identifying practical steps to help address the threats’.

While recognising the ‘shared interest in ensuring that terrorism and violent radicalisation be eliminated from the region’, the EU has consistently stressed that the fight against terrorism must not come at the expense of civil liberties and human rights.