Gender in Conflict

12 Dec 2014

By Christian Dietrich, Clodagh Quain for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by external pageEUISScall_made on 27 November 2014.

Violent conflict benefits few and tends to exacerbate the negative consequences of inequalities and marginalisation. The abduction of Nigerian girls by jihadi militia Boko Haram, the systematic rape carried out during the Syrian civil war, and the scores of Yezidi girls married off against their will by Islamic State (IS) in Iraq are some recent arresting examples of violence affecting girls and women.

Women, men and children experience and act differently in the context of violence and post-conflict reconstruction. In order to understand and address the gender-related consequences of conflict, an exclusive focus on sexual violence and the portrayal of girls and women primarily as targets has to be overcome. Such a narrative not only underestimates women’s capabilities for self-help, it can also hinder their empowerment. Just as men can be more than combatants, women can be more than just victims. In conflict, they can be civilians, breadwinners, peacebuilders and, at times, also combatants. By grasping the broad spectrum of women’s roles, a more nuanced understanding can be gained about gender in conflict; and more suitable policy responses adopted accordingly.

Gender in society

The concept of gender refers to the socially and culturally construed roles of women and men in a society. A focus on gender enables an analysis not only of the different roles, but also of the different opportunities that women and men have in a given social setting. Inequality might well be a cause for conflict, but conflict also amplifies inequality. Yet such instability does not necessarily aggravate gender inequality per se. In fact, its transformative impulses can provide room for those disadvantaged by gender roles to renegotiate their identities.

Gender inequality is a global phenomenon. For example, the difference in the rate of female parliamentarians in the first and last 50 countries ranked in the Human Development Index (HDI) is rather minor: 24.4% versus 17.1%, respectively. However, the vast majority of key peace agreements since the early 1990s were signed in relation to conflicts in developing countries, most of which rank considerably lower than developed countries on the UN Development Programme’s (UNDP) Gender Inequality Index (GII). All of the 20 most highly-ranked countries on the GII have ‘very high’ levels of human development, whereas all of the bottom 50 rank in the ‘medium’ or ‘low’ brackets of the HDI.

The participation of women in the political arena is often limited and, in some extreme cases, their rights as citizens are substantially curtailed. What is more, women’s representation varies substantially across policy fields: according to the Inter-Parliamentary Union, women are more likely to hold top positions in socio-cultural ministries rather than in ministries of defence, justice, interior or foreign affairs.

While men tend to dominate paid labour globally, it is women in lower middle income countries in particular who are often confined to specific economic roles without remuneration.

In conflict, social customs can additionally constrict women’s economic opportunities. That being said, the hardship imposed by conflict can necessitate and increase the tolerance for women transcending social customs and expanding their role beyond traditional conceptions.

Women as civilians...

While large parts of populations are affected by violent conflict, they may not necessarily be victimised, i.e. subjected to immediate physical harm. The role of women during the two World Wars (in what was then known as the ‘home front’) was shaped by the demands of the war industry and the vast mobilisation of men to be deployed at the front. This meant that many women took up work in factories and other areas previously considered men’s domains.

During the prevailing intra-state conflicts of the past two decades, civilian women also provided important support structures to warring factions. Voluntary or forced, their assistance can range from lending support to fighters by securing medical care, preparing food, or providing shelter.

War has detrimental effects on a range of services which are often taken for granted. By disrupting food supplies as well as health and education services, violence takes its toll on communities at large. Yet, on account of infant and maternal health, women have particular medical and nutritional needs that are likely to be insufficiently met during times of conflict.

Moreover, armed conflict also impairs social structures. When male breadwinners are absent, women frequently take on new responsibilities in families and communities. At the same time, women’s economic rights tend to be much more limited than those of their male counterparts. Where customs curtail women’s rights to land or property ownership, widows and/or female elders are left on the economic fringe or in a state of dependence when, for instance, the belongings of a deceased male are customarily passed on to his closest male relative. At the same time, women might also venture beyond socially assigned roles when providing for an extended family of surviving dependants.

The socio-economic consequences of conflict also often coerce civilian populations into unconventional markets and marginal work. The combination of various forms of stigma in the labour market and a need to substitute low household incomes means that prostitution often grows rapidly, as does organised crime or human trafficking. Between 2010 and 2012, the EU’s member states worked with 77 different countries on the implementation of policies which are sensitive to the role of gender in security. The EU also helps countries develop and implement national action plans that address awareness and reporting related to gender-based violence.

...victims...

Violence in conflict is itself multifaceted, encompassing political (kidnappings, torture and displacement), economic (robbery, ransom) or social forms (honour killings). Displacement, for instance, affects women, men and children equally in statistical terms, and amplifies the sense of vulnerability amongst those uprooted. Yet, culture and convention also have an impact: an interagency assessment carried out with Syrian refugees in Jordan showed that 40% of women and girls never – or rarely – leave their assigned shelter, as opposed to 28% of boys and 16% of men.

As a result of displacement, economic insecurity, and marred social networks, people’s environments become more unstable, thus increasing the risk of sexual violence. Such violence against women, men and children ranges from cases of rape to forced prostitution, sexual slavery, forced pregnancy and other forms of sexual assault. It is increasingly used as a tactic of warfare that causes sustained harm to communities through psychological trauma and the disintegration of social cohesion. The extent of the problem can be shocking: in the east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), 1.3 million women and 760,000 men – out of a population of 5 million in the area– were victims of sexual violence between 1994 and 2010.

This said, attempts to quantify cases of sexual violence among women and men are challenging at best, with those reporting sexual violence often running the risk of discrimination or isolation. A 2014 survey of Syrian refugees by UN Women, for example, found that 92% of women indicated that a woman who lost her virginity before marriage, regardless of circumstances in which this occurred, would never be accepted within their community. First-hand accounts from victims and eyewitnesses are therefore rare and any information offered to international organisations, NGOs and other actors in the field requires overcoming victims’ inhibitions to break the wall of silence.

In response to the occurrence of gender-based violence, the EU has initiated 100 projects directly targeting affected women and girls, worth over €80 million in total. More broadly, gender issues have been incorporated in the training of EU mission personnel – such as in EUSEC Congo, which addressed the care of sexual violence victims.

...combatants...

Women’s involvement in conflict is by no means a new phenomenon. When Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich attempted to murder St Petersburg’s chief of police in 1878, it marked the onset of greater female engagement in political violence. Since the first incidents of female terrorism in the second half of the 19th century, the sociological impact of a gender reshuffle became strikingly evident.

In the Second World War, women were, for example, deployed by the Soviet army as a tactic to encourage their more hesitant male counterparts to enlist, and an estimated 15% of the 820,000 women who served in the Red Army were combatants.

Attempts to recruit women into terrorist groups are intensifying. Between 1985 and 2006, it is estimated women accounted for 15% of overall suicide bombers globally, and this figure continues to rise. The social and cultural barriers that allow women to evade thorough examination at many security checkpoints, for example, have been exploited to carry out logistical tasks, but also suicide attacks. Men have also exploited the reluctance to inspect women by disguising themselves in female clothing, a tactic adopted, among others, by members of al-Qaeda.

At present, women and girls appear to make up about 10% of those leaving Europe, North America and Australia to link up with jihadi groups, including IS. With the increasing involvement of women in terrorist organisations, the EU has reiterated its commitment to controlling the flow of foreign fighters under the present counterterrorism strategy. For instance, the Union is determined to strengthen its security cooperation with the countries neighbouring Syria and Iraq.

...and peacebuilders

Empirical data demonstrates a strong correlation between the presence of women in representative bodies and the gender sensitivity of the resulting legislation. Following the cases of mass rape during the Rwandan genocide in 1994 (100,000-250,000 women were raped over a three month period), for example, the Rwandan cross-party Forum of Women Parliamentarians put forward a proposal for the state’s first comprehensive law, based on extensive consultations with female citizens, to combat gender-based violence.

Conflict can provide an opportunity for women to take the lead both in the political sphere, helping to close the gender gap present in state institutions, and in communities. One-third of the 26 parliaments with 30% or more female representatives are, for instance, in countries which recently experienced conflict.

Peace agreements set the scene for post-conflict reconciliation and peacebuilding. As they affect society as a whole, their inclusiveness heightens the chances for lasting peace: the inclusion of civil society in particular is key to preventing relapse into war. In order to be gender sensitive, peace agreements need rely on women’s participation in the negotiation processes as they add a different perspective to discussions, thereby bolstering the comprehensiveness of agreements and the sustainability of peace.

The legal framework

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) embodies the international community’s acknowledgement of the impact of war on women, and their role in building peace. Subsequent resolutions, notably 1820 (2008), addressed protection, prevention, participation – and placed a particular focus on sexual violence. This series of resolutions provides a framework where women are protected but also empowered to participate in peace processes.

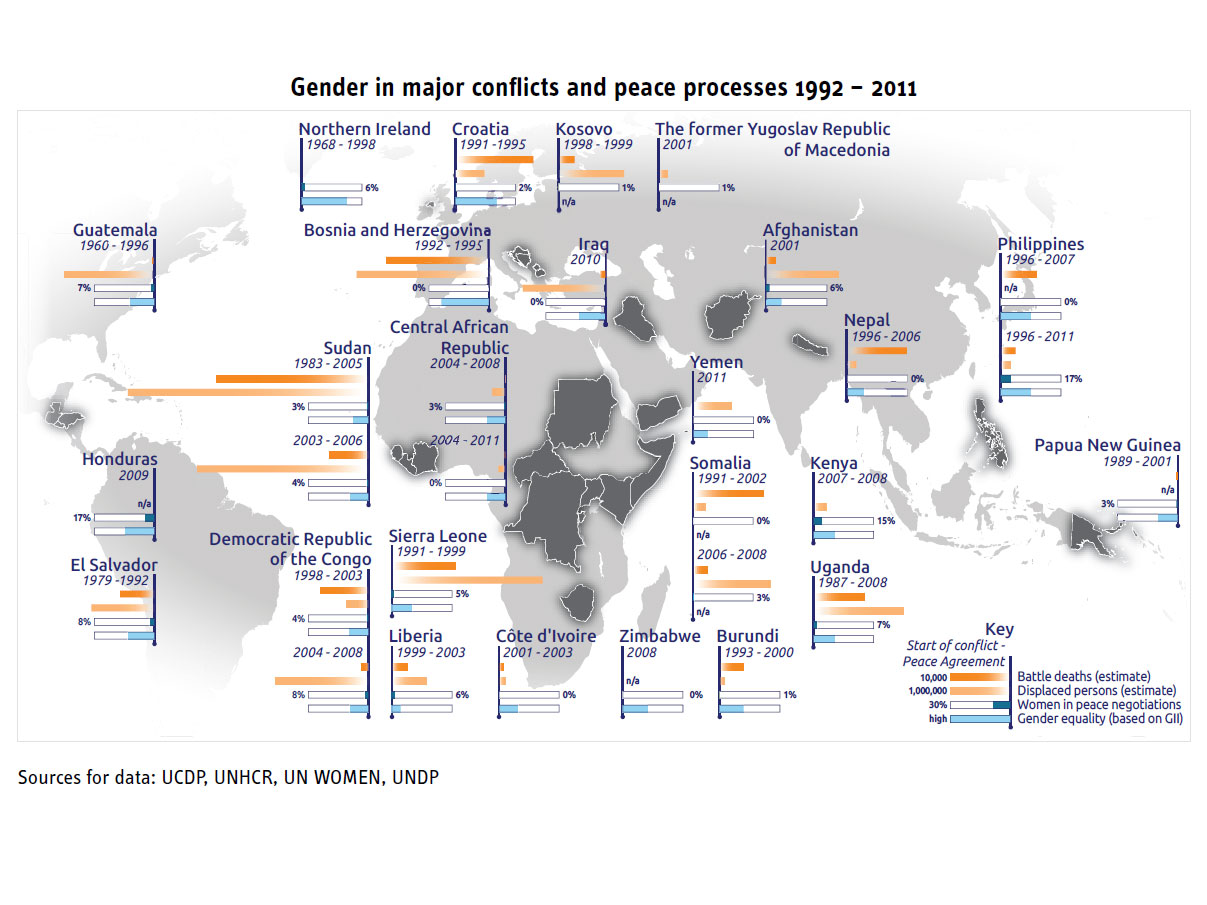

While strides have been made in their involvement in community-based peacemaking, paper-based commitments have yet to translate into practice. Women’s potential during peace processes remains virtually untapped. According to the European External Action Service, only 2.4% of signatories and 5.9% of negotiators were female in the ten peace accords signed since 1992 for which gender-sensitive data is available.

While the lack of data suggests that gender equality in peace negotiations is not yet considered a feasible goal, this deficiency is well known to most experts. The Council of the EU publishes regular reports in relation to the comprehensive approach and UNSCR 1325 and 1820. The Union invests in a range of related projects: for instance, a joint programme of the EU, UN Women and UNDP – funded by the Instrument for Stability’s Peacebuilding Partnership (2012-14) – addresses women’s participation and leadership in peacebuilding and post-conflict recovery.

Beyond their participation in peace processes, the EU also emphasises women’s involvement in the Union’s Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). Of the current 14 CSDP missions and operations, 9 have a gender adviser, and several have personnel devoted specifically to training and/or mentoring on gender issues.

A nuanced narrative

Both analysis and policies for gender equality and women’s empowerment have evolved considerably over the past decades. The EU, its member states, and the UN work in close partnership under the framework evoked by UNSCR 1325 and its successors. However, implementation is often cumbersome and tangible changes are rare.

Policies for peace and stability need to be gender-sensitive as both women and men can play a number of roles throughout violent conflict. While the effects of gender inequality can be exacerbated during conflict and put women – who are usually the ones disadvantaged by that inequality – and men in more volatile situations, the transformative nature of conflict can also be an enabler to redefine gender roles.

Suitable policy responses must address not only what women cannot do, but also what they can do as a result of conflict.

Christian Dietrich and Clodagh Quain are Executive Research Assistants at the EUISS.