Resurgent Radicalism

1 Apr 2015

By Prem Mahadevan for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

This chapter of Strategic Trends 2015 can also be accessed here.

The growing profile of the ‘Islamic State’, and its rivalry with al-Qaida, has heightened fears of terror attacks on Europe. The group has injected new enthusiasm into the global jihadist project by declaring itself a ‘Caliphate’ and thereby creating an illusion of military progress relative to the operationally stagnant al-Qaida. Europe needs to brace itself for the dual task of combating threats to its citizens at home while remaining alert to the strategic implications of Islamist insurgencies overseas.

A spate of terrorist attacks in the West since summer 2014 has alerted analysts to a fresh wave of radicalism from the Middle East. The rise of the so-called ‘Islamic State’ (IS) in Iraq and Syria is the most visible explanation of this phenomenon, but its roots lie deeper. ‘Leaderless jihad’, wherein terrorist groups devolve long-range operations to unaffiliated amateurs, has developed a forward momentum alongside ‘territorial jihad’, which aims to seize control of government structures. The two types of insurrectionary doctrine are complementing each other at a global level, confronting the West with a simultaneous threat of lone-wolf attacks at home and Islamist insurgencies in the developing world.

Although the IS is by far the most important contributor to this trend, its impact needs to gauged holistically. The group has profited from a growing sense of disillusionment among the international jihadist community with its main rival, al-Qaida. The latter was conceived and designed to operate from the sanctuary of a benevolent state or states, which it enjoyed when some governments were prepared to shelter its operatives for geopolitical reasons during the 1990s. Since the attacks in the US on 11 September 2001, however, the group has been homeless in a political sense. This has adversely affected its capacity to strike the West directly or to project influence into the Middle East. While many jihadist ideologues continue to stand by it, a younger generation of radicals has emerged since the 1980s that finds al-Qaida an antiquated brand. These younger radicals are gravitating towards the IS.

The January 2015 attacks in Paris are illustrative of the amorphous nature of contemporary jihadism. While the gunmen who attacked the satirical newsmagazine Charlie Hebdo claimed affiliation with al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), their accomplice who seized hostages in a kosher supermarket declared loyalty to the IS. From later reports, it seems as though all three men were operating semi-autonomously as products of a jihadist sub-culture that pushed them towards acts of violence, sans any concrete political grievance. Based on this event – as well as others in Europe, Canada, and the US – security officials have begun to wonder whether jihadist networks in the West are actually more of a mutated youth gang problem, instead of a coordinated terrorist offensive, requiring a bottom-up policing and community engagement solution.

What cannot be disputed, however, is that within its own neighborhood, the IS is coordinating military operations with the aim of creating a micro-state. The group’s capture of Mosul in June 2014 was a tremendous source of inspiration for jihadists across the world who had yet to score a comparable victory over government forces in their own regions. Since then, the IS’ foremost emulator seems to be Boko Haram in Nigeria, which has become even more ruthless over the last year. As was the case in Iraq, an increased willingness to inflict civilian casualties has terrorized large parts of the Nigerian state security apparatus, allowing jihadists to substantially undermine governmental authority. A corollary to this has been a significant growth in the role of organized crime in supporting jihadism – having acquired political dominance in certain pockets of territory, groups that were previously engaged in smuggling can now claim to be engaged in ‘trade’, and what was previously extortion can slowly be redefined as ‘taxation’.

There are thus, four explanatory pillars that account for the resurgence of radical Islamism. The first is the IS, and the alterative that it presents to the borderless model of jihad hitherto waged by al-Qaida. The second is al- Qaida itself, along with its affiliated groups. The third is the phenomenon that is loosely known as ‘lone wolves’ – individuals sympathetic to the cause of jihadism, but operating alone and with no formal training. This phenomenon has also produced ‘amateur’ jihadists – individuals who have received some training from an established group, but who operate autonomously and whose statement of subordination to that group is purely formal. The fourth pillar is organized criminal activity, which provides vital financial support for terrorist attacks.

This chapter will analyze how the rise of the IS has impacted, and will continue to impact, international terrorism. It will first situate the IS within global terrorism trends, to illustrate how these are being shaped by the group. Then, it shall demonstrate that the IS is feeding into an underlying pattern of governance collapse that exists in other parts of the developing world. This collapse has allowed the group to co-opt specialist talent into its ranks, giving it a structured and bureaucratic quality that makes its eradication all the more difficult. Next, the chapter will outline how the IS has diversified its funding sources to become a financially viable shadow state, taking particular advantage of its territorial dominance to generate revenue from new sources that are normally accessible only to governments. Finally, the chapter will examine the threat that developments in the Middle East and North Africa directly pose to European security.

Global overview

More than 13 years since the beginning of the ‘Global War on Terrorism’, the US and its allies have yet to fully destroy a single jihadist group. While al-Qaida Central – the core network originally formed in 1988 by Osama bin Laden and currently led by his deputy Ayman al-Zawahiri from Pakistan – has been severely damaged, it remains a functioning entity. Other groups have either voluntarily scaled back operations against the West, such as Hizbollah since 2001, or maintained a focus on regional targets instead of hitting Western homelands. For the most part, the US has been content to accord lesser priority to combating these groups, being preoccupied with homeland security and the vagaries of domestic politics.

The IS has emerged in this gap between the global rhetoric and local reality of US counterterrorism – the group harms Western overseas interests, far from Western jurisdictions, where the political will and operational means to combat it are proportionately weaker. Its media statements indicate that it perceives the US as averse to waging long-drawn counterinsurgency campaigns, and believes that it can outlast US air and even ground attacks. Despite heavy losses, the notion of persistence is central to its narrative. Here, it has history in its favor.

Even as US troops were withdrawing from Iraq in 2011, the IS was struggling to cope with 95 per cent manpower losses, which had been incurred as a result of cooperation between the Iraqi government, the US military, and Sunni tribesmen who opposed its hardline ideology. Between 2007 and 2010, the group fought a losing battle in which its leaders were tracked and killed, and its operational commanders scattered into the desert. However, its reconstruction began even during its downfall, when a number of cadres came into contact with former Iraqi military officials being detained at US-run prison camps. The result was a potent fusion of Salafist ideology with professional knowledge of army counterintelligence and urban warfare tactics.

In contrast, after 2011, the US lacked on-ground human intelligence assets in Iraq to push back against the jihadist momentum. This became evident during the first weeks of Operation Inherent Resolve, the aerial bombing of IS positions that began in summer 2014. Most sorties failed to engage any target, due to lack of identifying data. Although subsequent strikes were quite effective, notably around Kobane in Syria as a result of target-spotting by Kurdish militia, overall, the limited impact of airpower has been demonstrated. As already mentioned in Stra tegic Trends 2014, jihadists across the world have learned since 2001 to cope with the threat of aerial attack. Recognizing this, US officials have recently voiced concern that al-Qaida Central has proven surprisingly resilient against drone strikes in Pakistan. With the IS committed to carving out its own sovereignty in the Middle East, the question is now how al-Qaida can be prevented from adopting a similar agenda in South Asia once the US presence in Afghanistan ends completely.

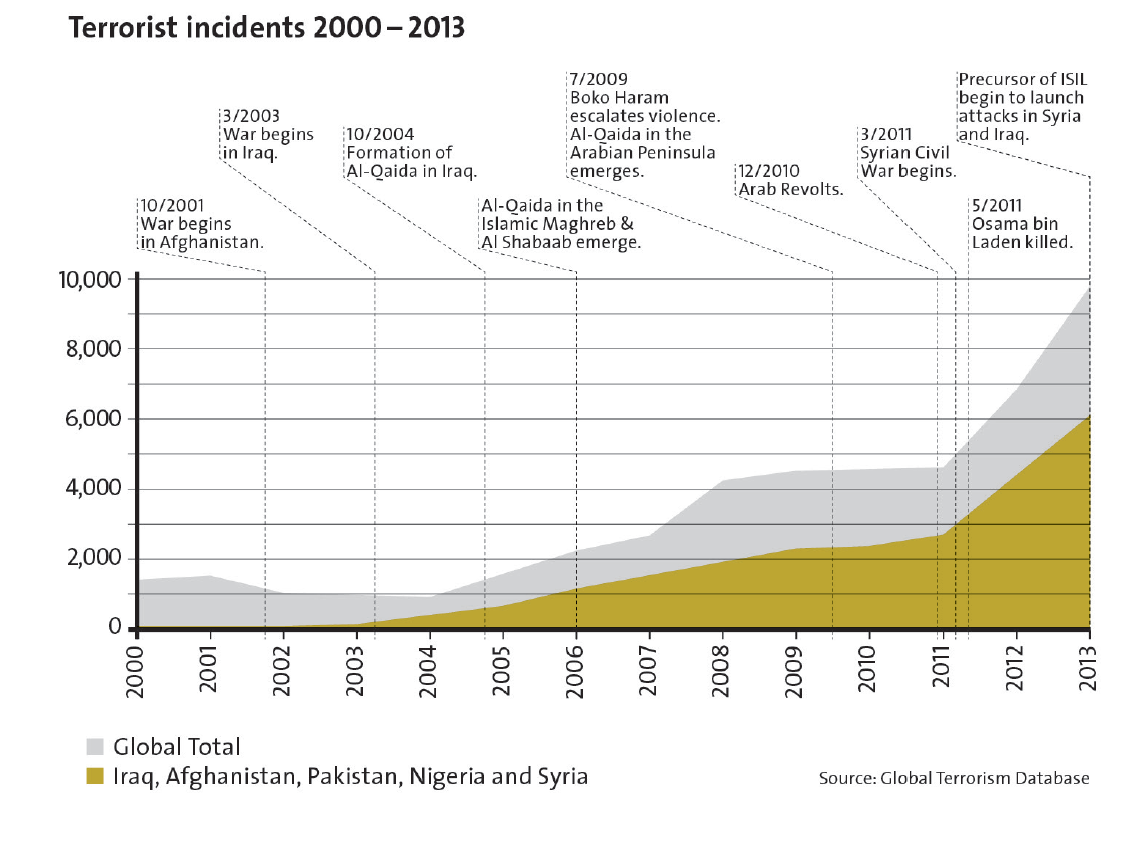

No doubt some precautionary measures need to be taken against a further rise in terrorist violence. Worldwide, such violence has risen five-fold since 2000, with 95 per cent of all deaths occurring in non-OECD countries. This latter statistic indicates that Islamist insurgencies quantitatively represent a much bigger threat to international security than ‘lone wolves’ in the West. During 2012 – 2013, fatalities increased by 61 per cent; the corresponding rise in 2013 – 14 was roughly another 25 per cent. Most attacks have occurred in just five countries: Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Nigeria. All are states where jihadist groups have a history of fighting for territorial dominance, and in some cases, exploiting local politics to propel their own institution-building agendas. In Libya, it is estimated that as many as 1700 militias are battling for supremacy, providing the IS with multiple entry points into the country through loaning its Libyan cohorts to local Islamists. The capture of Benghazi by Ansar al-Sharia in August 2014 and the subsequent declaration of an ‘Islamic Emirate’ there is viewed as the result of just such a process.

Furthermore, jihadist violence is proliferating largely independently of al- Qaida Central. A study of 664 terrorist/insurgent operations in November 2014 found that over 60 per cent of all fatalities were caused by groups that had no formal connection with the core al-Qaida network based in Pakistan. Worldwide, local jihadists are estimated to carry out 20 attacks daily, killing almost 170 people. This happens whether or not their organizational leaders have sworn a loyalty oath to al-Qaida chief al-Zawahiri. Such oaths, in fact, might only be an instrument in the power struggle between al-Qaida and the IS that could ratchet up their competitive dynamic.

During the 1990s, Osama bin Laden built a network of al-Qaida affiliates through two means: providing training and obtaining loyalty oaths from the leaders of more established groups. His successor al-Zawahiri inherited this network, but allowed parts of it to atrophy, particularly in Africa. Thus, the Nigerian group Boko Haram came to look for alternative patrons, eventually finding one in the IS. The two groups have created what appears to be a symbiotic partnership: in exchange for deferential statements from Boko Haram, the IS encourages African jihadists who cannot travel to Syria or Iraq, to go to Nigeria instead. Both organizations have enslaved women and girls, in particular from the Christian community in Nigeria and the Yazidis in Iraq. They justify such acts by claiming women as war plunder, to be bartered and sold as concubines. By specifying that they are targeting non-Muslims, they adopt an uncompromisingly exclusivist posture that appeals to other jihadist groups waging regional insurgencies. Attacks on Christian minorities in the Middle East and Africa increased substantially in 2014 over the previous year, more than doubling the world total.

Although al-Qaida is in no way averse to the brutal tactics of the IS, it disagrees with the group regarding their strategic value. Al-Qaida’s leadership has tended to be sensitive to Muslim public opinion and therefore, at least at the rhetorical level, advocates restraint in targeting co-religionists. The IS, on the other hand, is not only openly sectarian, but adheres to a rigid interpretation of Islam that allows it to openly brand all who disagree with it as apostates worthy of being killed. A very broad targeting policy gives the IS more opportunity to demonstrate its presence than al-Qaida, which is now regarded with disdain by a new generation of jihadist sympathizers, looking to align with a group that has a successful operational track record.

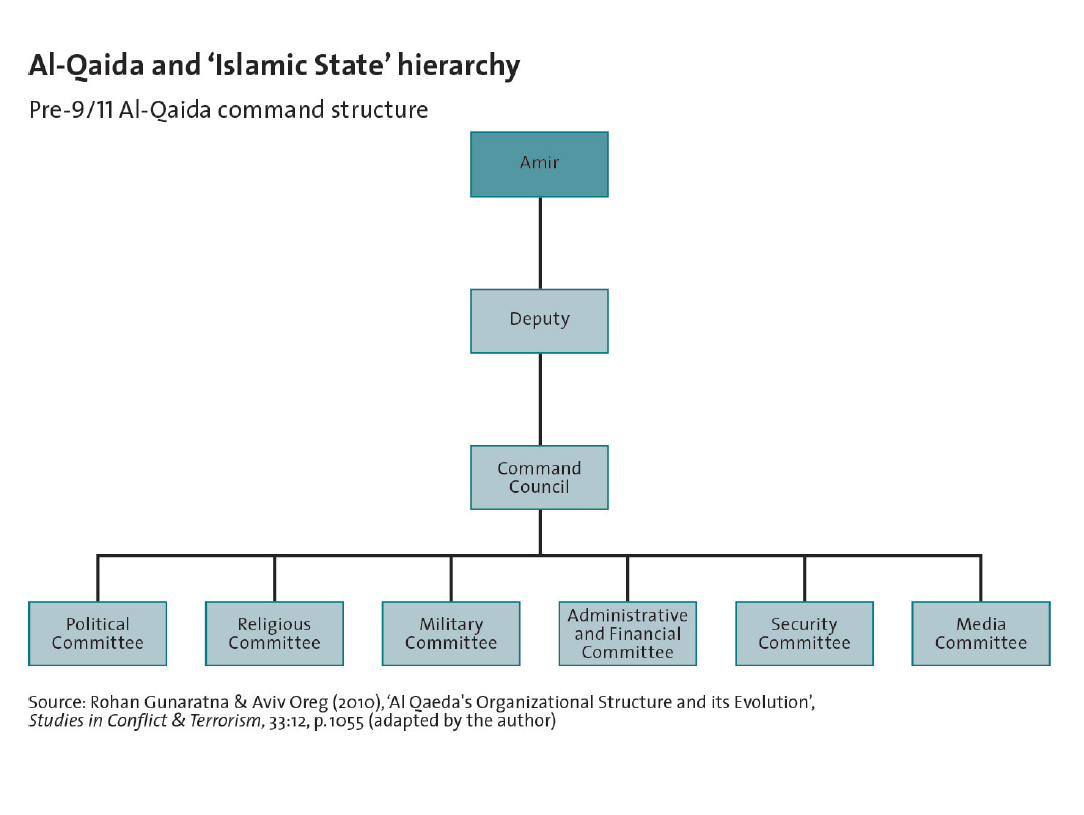

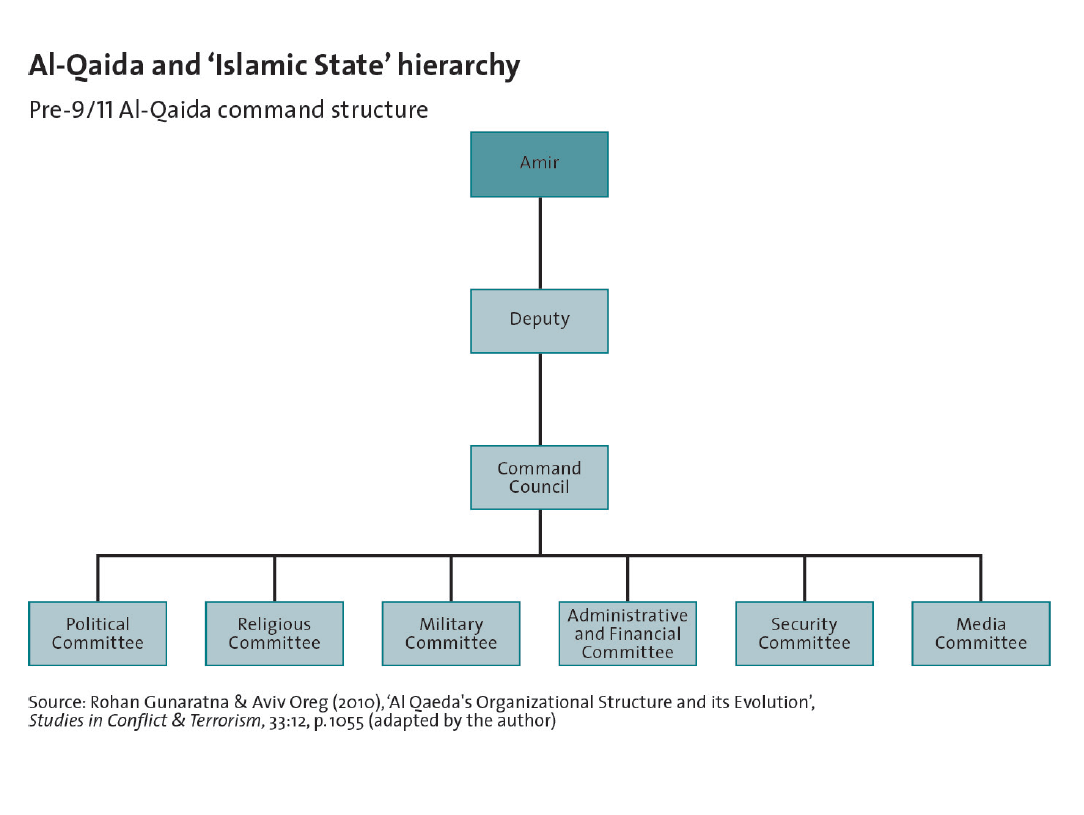

There is a fundamental difference between al-Qaida and the IS that partially explains their differing trajectories and fortunes. Al-Qaida saw its own role in global jihad as being merely a facilitator in the re-establishment of a grand Caliphate rather than being the founder. The IS, however, sees itself as the Caliphate’s foundational core, which means that it is willing to take responsibility for governance – something al-Qaida never did, even when it enjoyed safe haven in Sudan and Afghanistan in the 1990s. Al- Qaida is a parasitic organization that needs to be protected by a state structure. With no state willing or able to shield it from US counterterrorism efforts since 2001, the relevance of its strategic concept to the international jihadist project has dwindled. The IS seemingly offers a solution: creating a micro-state in regions of poor government presence that can serve as a platform for imposing a rule of puritanical Islam.

Terrorism through governance

After setbacks in 2007 – 2010, the resurgence of the IS was enabled by the Syrian civil war and the simultaneous rise of sectarian politics in Iraq. Syria provided the group with a hinterland, in which to build an operational base. Thereafter, the IS initiated two campaigns: ‘Breaking the Walls’ and ‘Soldiers’ Harvest’ intended to free its cadres who were being held in Iraqi prisons and to assassinate government officials, respectively. Even as it was thus engaged, the Shi’ite regime of then Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki systematically alienated Sunni Arabs by excluding them from job opportunities and refusing them any method of peaceful protest.

What resulted was a Sunni tribal uprising; the IS quickly jumped on the bandwagon and turned it to its own advantage. By forging tactical alliances with Sunni militias, it built pockets of influence in the Sunni heartland away from the Syrian border through relatively sophisticated, intelligence-led operations. In the north, it gradually encircled and infiltrated Mosul, paralyzing the local administration while keeping the Baghdad government off balance through a relentless car-bombing campaign. When the group finally occupied Mosul in June 2014, its clandestine networks in the city had already done the job of scaring away local security forces commanders and exploiting sectarian rifts in the army. The actual occupation was thus achieved relatively easily.

Such meticulous organization and planning had originated from the former Iraqi army officials who joined the IS while imprisoned alongside its ideological leaders in 2007 – 2010. Their circumstances were peculiar to Iraq: left with no source of income after US occupation forces disbanded the Ba’athist political infrastructure, many fell in with insurgent groups.

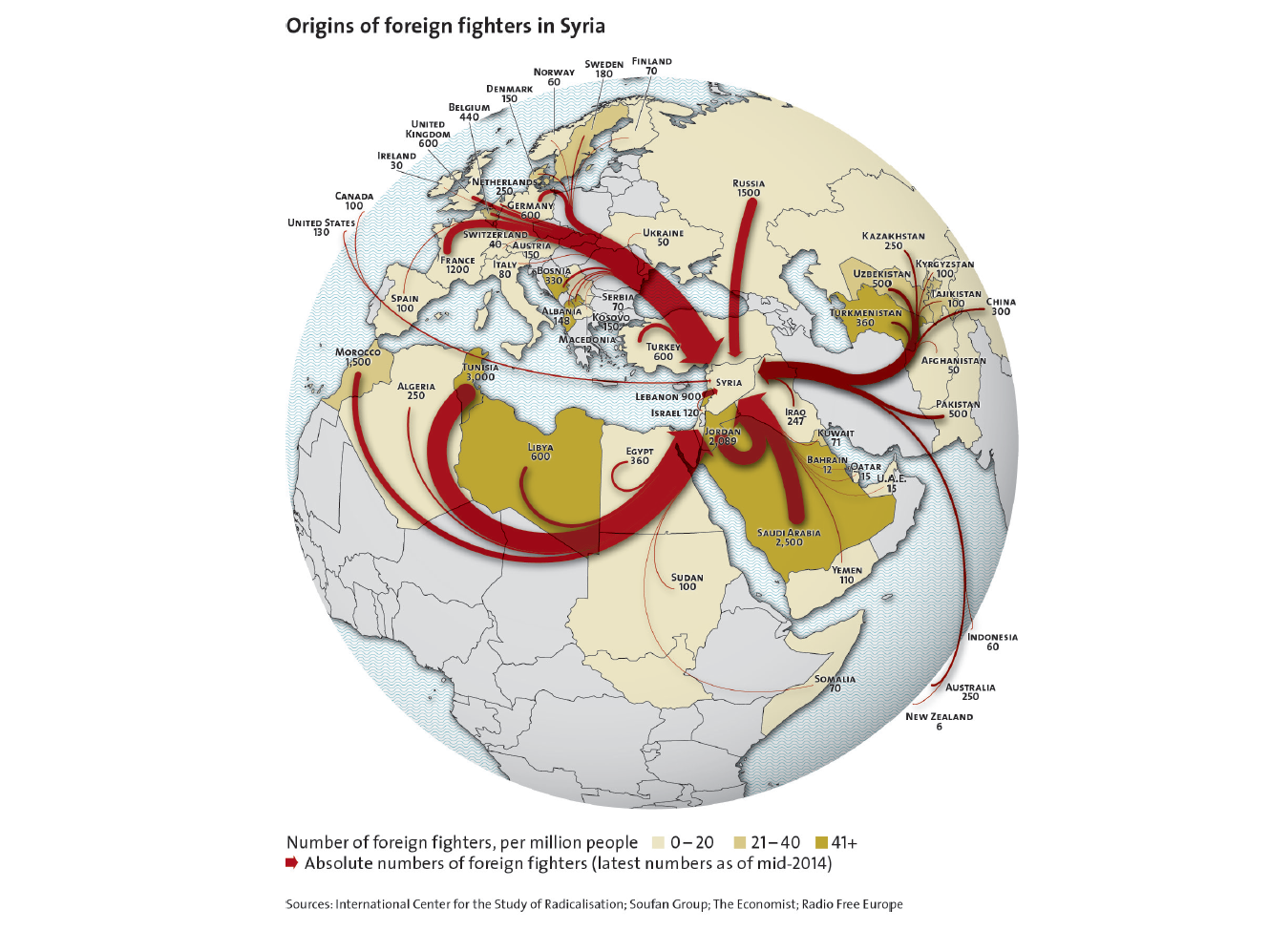

The tactical acumen of these former soldiers when combined with the fanaticism of radical Islamist ideologues, made for a lethal combination as violence in Iraq steadily increased. Admittedly, such a convergence of interests is unlikely in other jihadist hotspots across the world, but even a limited overlap of agendas is enough to change the dynamics of a conflict. The top IS commander in Syria, for example, is thought to be an ethnic Chechen who previously served in Georgian military intelligence. Many of the battlefield successes attributed to jihadist groups in Syria are believed to have been orchestrated by veteran insurgents from the Caucasus. A decade of experience in fighting Russian troops has made Chechen Islamists tactically adept, to a degree unusual among foreign fighters travelling to the Middle East. This has allowed them to assume a disproportionate number of senior positions within the anti-Assad forces in Syria.

Even without the help of former soldiers, jihadist groups are gaining potency through skill-sharing among themselves. In 2003, the IS (then known by a different name) pioneered suicide bombings in Iraq. It had learned the efficacy of this tactic from al-Qaida, which in turn had acquired it from Hizbollah in the early 1990s. At the start of its bombing campaign in Iraq, the IS was in a junior partnership with al-Qaida. Over a period of time, the power balance shifted, as al-Qaida languished under the weight of international counterterrorism pressure, and the IS engaged in indiscriminate attacks against Iraqi Shi’ites, Sunnis, and US occupation forces. Its much more visible presence in the conflict area allowed the group to develop an independent funding stream from foreign donors, which then attracted recruits from the wider Middle East and beyond.

The recruits were a mix of jihadist veterans from other combat theaters and new volunteers. Initially motivated by a desire to drive out Western troops from Muslim lands, over a decade, the influx morphed into a quasi-criminal assortment of freebooting mercenaries. Many had criminal convictions in their home countries. For example, a number of Lebanese-Australians who had been involved in street gang violence left to fight in Syria after 2011. Chechen exiles from Turkey and Austria, among other countries, found the IS as a natural home for their jihadist sympathies. Over 100 Kosovar Albanians – part of an ethnicity that has tended to be staunchly pro-Western out of gratitude for the NATO intervention of 1999 – joined the IS and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria.

What unites the motley crowd of foreign fighters with the IS, al-Qaida, and regional jihadists is a common quest for a new political identity that cuts across current international and regional boundaries. The IS has moved to the first rank of jihadism by building a governance model that many Islamists find attractive after perceiving themselves as marginalized in their home societies. Disillusionment with a lack of integration into local power structures has made groups such as Boko Haram, Abu Sayyaf and Mujahidin Indonesia Timur, as well as factions of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, keen to adopt new tactics for seizing power. Boko Haram, for instance, has shifted from guerrilla attacks to clearing and holding territory in the face of Nigerian government offensives. It has seeded approach routes to its strongholds (roughly 20 towns in three states) with improvised explosive devices (IEDs), much as the Taliban have done in Afghanistan, to drive up the human and material costs of counterinsurgency. Apparently copying the IS, it has targeted the Shi’ite community in Nigeria with the aim of polarizing intra-Muslim relations and creating a captive constituency among Sunnis. The group is also feeding into the historical identity of ethnic Kanuris who once ruled over an Empire founded in the modern-day province of Borno. Its trans-border operations into Cameroon and Chad are a repudiation of current nation-state boundaries, just as the IS is meant to signify a rejection of the Sykes-Picot agreement.

The IS has used the retreat of governance in Iraq to set up its own administration, the first objective of which is counterintelligence. Accounts from IS-controlled territories suggest that the group prioritizes the identification of government loyalists and religious minorities when it enters a new area. Computerized databanks have been created, based on financial records and government files, to identify persons who might pose a security risk to the group. Besides coercing municipal workers to continue their jobs (with pay), the IS also assigns some of its foreign volunteers to administrative duties, thereby showing that it is committed to bureaucratization. The group matches volunteers to their aptitude and previous career training, and has even put out job advertisements for oil industry experts. Allegedly, the IS eventually hopes to print its own gold-supported currency, thereby strengthening its claim to full statehood. Towards this, it is reported to have established its own bank in early 2015 and announced a ‘budget’ of USD 2 billion, the bulk of which has been allocated towards salary payments and civic service provision.

Al-Qaida cannot hope to match this. With the IS having appeared amidst the jihadist fraternity, it now faces a loyalty problem among its affiliate groups. Some jihadists that operate in conflict zones believe that the IS model is more applicable to them, particularly since they do not share al-Qaida’s long-standing fixation with attacking Western homelands. Others, probably out of organizational inertia and lack of past contacts with the IS leadership, are inclined to abide by their vows of loyalty to al-Qaida chief al-Zawahiri. The IS itself is believed to be courting defections from the latter camp, creating factional tensions. One example is the Dagestan network of the so-called ‘Caucasus Emirate’ in southern Russia. While the bulk of the ‘Emirate’ has remained loyal to al-Qaida, a powerful sub-group is thought to have switched allegiance to the IS. The implications of this are two-fold: Either the mainstream ‘Caucasus Emirate’ will now be compelled to emulate the IS model and attempt to set up a parallel administration, or it will seek to carry out expeditionary attacks on Russian cities to compensate for its overall military weakness. In any case, Russian authorities are prudent in anticipating a rise in terrorist violence.

Diversified funding through territorial dominance

A jihadist group with at least partial control over territory can substantially increase its fund-generating ability by taxing legal and illegal business activity and/or smuggling high-value contraband in bulk quantities. The IS has leveraged such control to become the richest terrorist group in the world, with a total worth of roughly USD 2 billion. Al-Qaida Central, on the other hand, has been systematically starved of funds since 2001. In 2005, it even had to ask the IS (then known as al-Qaida in Iraq) for USD 100,000. In the following years, the IS’ strategic fortunes rose in tandem with its finances. From initially relying on private donors in Sunni Arab states, the group entered the lucrative oil-smuggling trade. It thereby acquired an independent funding base that lay well outside the jurisdiction of US law enforcement agencies. This put it at an advantage over al-Qaida, which depended on long-distance money trails that were being aggressively targeted by financial counterterrorism measures.

The IS symbolizes a convergence between organized crime and terrorism. During the Cold War, both terrorists and gangsters received some measure of protection from state authorities in order to function. This protection often only amounted to passive tolerance and nothing more, but without it, they had no hope of survival. Thus, Palestinian terrorist groups like the Black September Organization were covertly sheltered by the intelligence services of Warsaw Pact countries, while the West allowed organizations like the Sicilian Mafia to establish parallel states in post-war Italy, intending to use them to thwart the spread of communism. After 1989, both arrangements collapsed. Terrorist and criminal organizations on both sides of the Cold War ideological contest found themselves simultaneously orphaned, and began collaborating with each other on a more frequent basis. As outsiders in the new international system, they had little to lose.

Scrutiny of terrorist funding over the last two decades reveals that mercenary imperatives can forge alliances across all ideological boundaries. For example, during the early 2000s, Hizbollah obtained weapons from Russian mobsters in Central America. Introductions were provided by a former Israeli military official who had grown friendly with a senior Hizbollah operative through business ties developed in the Congo. Shi’ite Hizbollah had also helped Sunni al-Qaida enter the West African diamond smuggling trade during the Liberian civil war. More recently, it is believed that al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) has grown heavily involved in the Latin American drug trade. In exchange for protecting cocaine shipments travelling across North Africa and bound for Europe, the Algerian jihadist group is reportedly paid a 15 per cent commission on the profits.

Other groups in Africa obtain funding from charcoal exports (al- Shabaab) and maritime piracy (Boko Haram). None of these is exclusively dependent on one source of income. Depending on local conditions, it can also be possible to abduct Western nationals who are either visiting as tourists or working in the country as technical experts or NGO activists. From 2008 to 2014, governments paid anywhere between USD 125 and 165 million in ransoms for hostages taken by al-Qaida affiliates around the world, the majority of them in the Maghreb. Exact figures are difficult to obtain since many Western countries disguised the payments as ‘foreign aid money’. The actual kidnappings were done by local criminals who were paid a commission for each snatch. Victims did not always have to be foreigners: In South Asia, the Pakistani Taliban has for several years run a kidnapping racket focused on businessmen, politicians, and government officials. Intelligence on prospective targets is obtained through domestic servants. Understaffed law enforcement agencies, worried for the safety of their own personnel, tend to take a hands-off approach, often advising victims’ families to negotiate a ransom on their own.

The scale of rent collection by terrorist groups is directly related to their territoriality. Two of the biggest funding sources of the IS are peculiar to the Middle East: oil and antiques. Before the US-led aerial bombing campaign of its forces, the IS was estimated to be capable of producing 280,000 barrels of oil per day, of which it actually sold only 80,000. This alone is thought to have yielded a daily income of USD 1 million. Oil sold at half the market price to neighboring countries made the IS inherently competitive as an energy producer – hence, much of the coalition’s effort has since gone into attacking its oil installations. These are likely to have suffered serious damage by early 2015, causing a shift to other sources of revenue generation. Antiques play a crucial role here: the archaeologically rich terrain of Iraq and Syria literally offers a treasure trove of diggings. As with kidnapping and drug trafficking, the actual theft is often done by professional smuggling syndicates, with the IS content to accept a tax of at least 20 per cent of the profits. Satellite imagery of countries affected by the Arab Revolts of 2011 has indicated a massive rise in the number of illegal excavations of archaeological sites. While not all of these are related to jihadist violence, there is still a strong suspicion that the trade in artifacts, which ends mainly in European and US auction houses, is fuelling terrorist activity in the Middle East.

Drug and human trafficking and antique smuggling are favored by jihadist groups because they have a dual purpose: to generate operational funds and to harm the ‘enemy’ politically. Since the 1980s, Islamist terrorists have justified involvement in the global drug trade as a way of undermining Western societies, which they perceive as morally degenerate. With the IS now in physical control of territory in the Middle East, sex slave trading has become a tool for asserting political dominance in local cultures. Even antique smuggling is seen as part of a ‘cleansing’ process, to rid the IS of pagan idols that contravene its core religious principles and legitimacy. To their supporters, there is little contradiction in jihadists being pious but waging war against non-believers through street-level crime. In the absence of state sponsorship as the major source of funding it had been during the Cold War, social acceptance of profiteering in the terrorism industry has increased.

The result has been an increase in the operational capability of terrorist groups, which can now develop ties with organized crime for sustained logistical support. Although the actual costs of conducting a terrorist attack in the West are relatively low, contact with criminal elements is essential for any sophisticated and large-scale operation. Even if such contact is delegated to secondary members of the jihadist network, it remains vital because its absence would drive up the logistical expenses of an attack to levels that might not be within reach of the core operatives. For example, the 2004 Madrid bombings are estimated to have cost approximately EUR 8000, but the indirect costs of clandestine travel and supporting activities would have been at least five times that figure. Some of these hidden costs were collaterally absorbed by criminal syndicates such as the Italian Camorra, allowing the attack cell to concentrate on the actual bombings.

In recent years, Europol has been particularly alarmed by high levels of illegal immigration from conflict-prone countries in the Middle East and South Asia. Among diaspora communities, illegal elements of the Pakistani diaspora might be the most susceptible to fusing crime and terrorism. This is partly because of the strong role that Pakistan plays in the Afghan heroin trade, serving as a transit country for 40 per cent of all shipments. Rivalry between different trafficking syndicates, often based on nationality (for example: Pakistani versus Turkish), has led to a sense of marginalization even among the immigrants themselves. This makes for a fertile ground for jihadist recruitment, and many ‘lone wolf ’ terrorists in the West have been found to have a petty criminal background. De-radicalization programs offer little protection against them because criminal-jihadists, unlike idealistic volunteers for jihad who do not know the realities of combat, are morally hardened.

Homeland security threat

Although the terrorist threat to Europe is miniscule in absolute terms, it still has the capacity to undermine inter-religious relations within European societies. For some years now, there has been a slow drumbeat of ‘lone wolf ’ attacks, which gathered pace during 2014. From the May 2014 shooting at the Jewish Museum of Belgium to the Charlie Hebdo attack, lone wolves and ‘amateur jihadists’ (those who have received some paramilitary training, but operate on their own initiative) have demonstrated an astute political sense in their targeting pattern. They have hit locations that have a high symbolic value but are relatively easy to access, thus requiring little preparation for an assault. They have fed into larger currents in the domestic politics of many European states – such as France, Norway and the United Kingdom – which see multiculturalism and immigrant assimilation as failed experiments. Hence, they have lit a spark that could in future years develop into a serious domestic security threat to Europe.

Even more worrying, lone wolves and amateur jihadists have had the effect of splitting policy attention between homeland security and combating large-scale terrorism overseas. With much of the media transfixed by Charlie Hebdo attack, little attention was paid to the near-simultaneous massacre of approximately 2000 people in northeast Nigeria. Through this massacre, Boko Haram consolidated its hold over Borno province and came a step closer to emulating the territorial dominance of the IS in Iraq and Syria. The group is now thought to have a strong presence in as much as 20 per cent of Nigeria’s territory – an area the size of Switzerland. Meanwhile, in Mali, jihadists who had previously been routed by the French air and ground offensive in 2013 are quietly returning. Among their first initiatives upon recapturing territory is to identify and eliminate all ‘collaborators’ who assisted the French. There is little that can be done to resist this trend, due to policy preoccupation with security threats closer home.

Much speculation has surrounded the question of foreign fighters travelling to join the IS. The number of EU nationals fighting with the group is estimated at anywhere between 3000 and 5000. Roughly 1200 come from France, home to Europe’s largest Muslim and Jewish populations and thus considered a prime target for any spillover of violence from the Middle East. With Muslims representing eight per cent of the French population, but constituting around 70 per cent of all imprisoned criminals, jihadist recruiters have a simmering pool of resentment to tap into. Among political analysts, questions are being raised about whether the French effort to integrate marginalized communities is too much or too little. The answer to this would also be pertinent for Belgium, Denmark, and the UK, all of which have been heavily affected by IS recruitment campaigns. The group has revolutionized online radicalization, through a smart propaganda campaign backed up by money power and technical expertise.

To begin with, the IS gives great emphasis on relaying the positive impressions of its rank-and-file recruits. This is in contrast to al-Qaida, which mostly allowed senior commanders to appear in its media releases and had them deliver drab, politically-loaded rants. IS members, on the other hand, narrate how life in the IS is appealing at a mundane level and talk about how civic services are provided to ensure a high standard of living. Although the truth is vastly different, impressionable and psychologically dislocated youth from around the world find the IS fantasy a tempting one. Although many join the group with the express purpose of waging violent jihad, a sizeable minority seem to actually believe that the IS represents a new experiment in state-building and wish to contribute to it out of pseudo-altruistic motives. Certainly, the Syrian civil war provides a cause to rally around, given the fierce repression practiced by the Damascus regime.

To avoid disillusioning its more idealistic supporters, the IS ensures that public disgust with its extra-judicial executions, including the beheading of Western journalists, does not swell into a counter-movement. Some beheading videos have been edited to leave out the goriest footage, thus presenting an illusion of a ‘suffering-free’ death. Those who are ideologically attracted to the IS model of politics find such killings morally palatable, since they do not have to confront the human tragedy that is inherent in the act. At the same time, such footage, together with photographs of prisoner executions in official IS publications, exerts a psychologically strong pull upon viewers. Al-Qaida, forced to remain a de-territorialized group whose members are on most-wanted lists, lacks the resources, time, and space to match the sophistication of IS propaganda.

European security experts are sure that the influx of foreign fighters to the IS is a potential long-term problem. What they are not clear about is how this problem will manifest itself. The worst-case scenario – that of European jihadists returning home to create mayhem – is not assessed as very likely. This is because surveillance technologies introduced over the past decade have given law enforcement agencies a fairly good picture of their activities once they re-enter Europe. Only resource constraints and legal barriers (in some cases) prevent detailed case-specific knowledge of the public risk that each individual poses – both problems are unavoidable in free societies that do not wish to become police states. Instead of carrying out attacks themselves, such jihadist veterans might find it easier to serve as motivators, exploiting freedom of expression laws to inspire future generations towards radicalism and if incarcerated, to win over prison inmates. This is a more insidious challenge, as Dutch investigators have discovered. Despite initial successes in scaring off aspiring jihadists from pursuing their plans, authorities have noted that in recent years, potential terrorists have learned how to game the system. The latter are now aware of their legal rights, and the limits of police power to intercept and question them. Consequently, they are becoming better at disguising their activities and staying below the surveillance grid. The most likely attack scenario would be one of ‘amateur’ terrorists, with a strong criminal background, carrying out operations based on logistics support obtained through gang contacts. While these preoccupy the attention of European security officials, Islamist insurgencies in the Middle East, North Africa, and possibly South Asia will likely make a determined grab for political power.

The IS is the key to the unfolding trend. As the primary pillar of jihadist resurgence since the death of Osama bin Laden and the Arab Revolts of 2011, its fate will closely shape other groups’ enthusiasm for ‘territorial’ jihad. Meanwhile, al-Qaida and its affiliates are seeking to assert their continued relevance by encouraging attacks on Western homelands. Here, the third pillar – lone wolves and amateur jihadists – becomes crucial. It gives al-Qaida a strike capability which the IS might be compelled to acquire as well, once its cadres in Iraq and Syria are sufficiently demoralized by military setbacks against coalition forces. In such a situation, they will need fresh doses of courage injected into them through long-distance attacks in Europe, North America, or Australia. The fourth pillar – organized criminal activity – would serve as an enabler of such attacks, both financially and logistically, and in certain cases by providing additional manpower from the prison population of European states. Taken together, these four pillars of radicalism suggest that whatever the outcome of the campaign against the IS in the Middle East, Europe needs to remain vigilant.