Peacekeepers Under Threat? Fatality Trends in UN Peace Operations

5 Oct 2015

By Jair van der Lijn, Timo Smit for SIPRI

This policy brief was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageStockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)call_made in September 2015. Republished with permission.

Summary

It is often claimed that contemporary United Nations peace operations perform their functions in increasingly dangerous environments and are therefore more likely to suffer casualties than in previous years. Yet the data on deaths among UN peacekeepers between 1990 and 2015 indicates that fatalities have not become more frequent, neither in absolute terms nor, especially, in relative terms. In fact, the rate of fatalities among uniformed personnel in UN peace operations has steadily decreased in relative terms since the early 1990s. While the number of hostile deaths (i.e. fatalities due to malicious acts) has increased somewhat in recent years, this is mainly due to the high number of fatalities in MINUSMA, which is one of the most deadly UN peacekeeping operations ever. All other ongoing UN peacekeeping operations have suffered relatively few fatalities and hostile deaths, and fewer than many UN operations that were active in the 1990s.

Introduction

Since the United Nations established its first peacekeeping operation—almost 70 years ago—more than 3300 people have died serving the UN in the pursuit of peace. On 29 May 2015, the International Day of UN Peacekeepers, the Dag Hammarskjöld medal was awarded posthumously to the 126 military personnel, police and civilians who lost their lives in 2014 while in the service of the UN. At the commemoration ceremony at the UN Peacekeeping Memorial in New York, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon remarked that for the seventh year in a row more than 100 peacekeepers had died serving the UN across the world. He attributed this to the fact that the UN deploys more peacekeepers than ever and that UN peacekeepers operate in ever more dangerous environments. [1]

These arguments are frequently used. For example, the US Ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, told the UN Security Council in October 2014 that ‘peacekeepers in 21st century missions face unprecedented risks . . . because we are asking them . . . to take on more responsibilities in more places and in more complex conflicts than at any time in history’.[2] In addition, the High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations stressed throughout its final report issued in June 2015 that peacekeepers are operating in increasingly dangerous and hostile settings, and that this will likely increase in the future.[3]

Indeed, in recent years UN peacekeepers have been attacked by violent extremist groups (e.g. in the Central African Republic, CAR, and Mali), held hostage by jihadists (in Syria), and deployed to areas in which there is little or no peace to keep (CAR, Darfur, Mali, South Sudan). Two-thirds of all UN peacekeepers operate in countries where armed conflict is ongoing and in some cases intensifying.[4] Meanwhile, since the end of the 1990s peacekeeping mandates have become more robust—often including the authorization to use force and sometimes even offensive action. Yet most peacekeepers are neither sufficiently trained, nor equipped, to deal with asymmetric threats and well-armed adversaries in addition to the set of tasks they are expected to perform. In other words—while any death in the service of the UN is inherently tragic—it is hardly surprising that peacekeepers are losing their lives in the line of duty.

However, is it correct to assume that contemporary peace operations are more dangerous than before? To answer that question, this policy brief analyses trends in (relative) fatality rates among personnel in UN peace operations since 1990, with a particular focus on fatalities resulting from malicious acts (hostile deaths).[5] The conclusions drawn are that operations have not become significantly more dangerous, at least not in terms of fatalities, and that contemporary operations are generally not suffering greater losses than their predecessors.

Trends in the Absolute Numbers of Fatalities

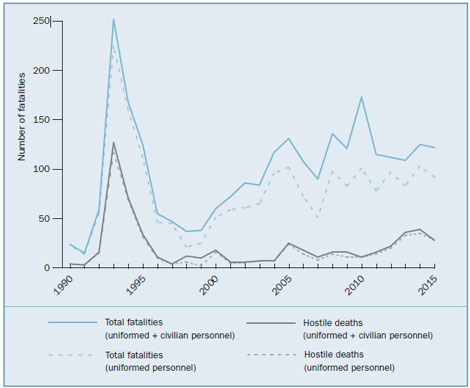

Figure 1 shows the total number of fatalities per year among all personnel in UN peace operations (peacekeeping operations and special political missions) since 1990. It shows an increase in fatalities from 1998 to 2005. Since 2006 there has been no clear upward or downward trend, and except for 2010 (when nearly 100 peacekeepers involved in the MINUSTAH operation died as a result of the Haiti earthquake) the fatality levels have remained more or less within a stable range. The same is true when focusing only on fatalities among uniformed personnel (military and police).

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 1. Fatalities among personnel in United Nations peace operations, 1990–2015.

Notes: The values for 2015 are projections based on the fatalities in the first half of the year (up until 2 July) and do not represent the number of deaths in 2015 so far.

Source: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO).

By contrast, the number of hostile deaths has increased more clearly in recent years. The number of personnel killed by malicious acts in 2013 and 2014 was at its highest level for 20 years. However, while this is cause for great concern, recent facility levels are still much lower than those in 1993 and 1994, when the UN suffered heavy losses in the former Yugoslavia (UNPROFOR), Cambodia (UNTAC) and Somalia (UNOSOM II).

Moreover, it is worth remembering that malicious acts are not the main cause of deaths among peace operations personnel. Illness and accidents (i.e. causes that are not directly related to hostile environments) still account for the majority of deaths, something that remains underreported. Malicious acts usually do not account for more than 10 to 30 per cent of all fatalities per year, although the proportion of hostile deaths has increased in the past few years.

Trends in the Relative Numbers of Fatalities

Notwithstanding the above, when comparing fatality levels over multiple years, it is necessary to consider the exponential increase in UN peace operations personnel as well. Between 1990 and 2015 the number of uniformed personnel in the field has increased tenfold, from approximately 10 000 to more than 100 000. Figure 2 shows the number of fatalities per year for every 1000 military and police (on average) in UN peace operations. The reason for focusing on uniformed personnel is that no comparable data is available on civilian staff numbers before 2004, whereas the monthly statistics on uniformed personnel go back to 1990.

Click image to enlarge.

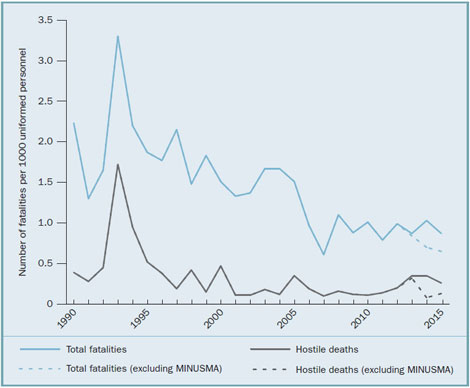

Figure 2. Fatalities per 1000 uniformed personnel in United Nations peace operations, 1990–2015.

Notes: The values for 2015 are projections based on the fatalities in the first half of the year (up until 2 July) and do not represent the number of deaths in 2015 so far. See box 1 for details of the methodology. MINUSMA = UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali.

Source: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO).

Surprisingly, the trend in these figures seems to contradict the assumption that UN peace operations have become more dangerous. Contrary to expectations, the number of fatalities per 1000 uniformed personnel has steadily decreased over the past 25 years. Whereas most years between 1990 and 2005 recorded values well over 1.5 per 1000—with a peak of 3.3 per 1000 in 1993—the trend line clearly falls in 2006 and 2007. Since 2008, fatalities among uniformed personnel have remained stable at about 1 per 1000.

Looking at the number of hostile deaths per 1000 uniformed personnel, there is also little evidence suggesting that peace operations have become significantly more dangerous. While there has been a relatively sharp increase in these figures since 2010, the peaks in 2013 and 2014 (0.35 per 1000) are not unusually high compared to those for the past 25 years, and they are approximately five times lower than in 1993 (1.72 per 1000). In fact, when MINUSMA (Mali) is excluded from the analysis, 2014 actually had the fewest hostile deaths per 1000 since 1990 (0.08 per 1000).

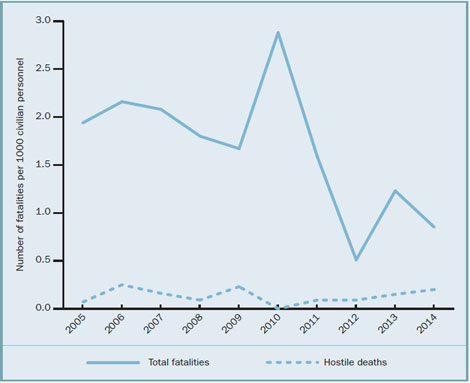

Although the majority of fatalities in UN peace operations occur among military and police, the absolute numbers of deaths among civilian staff are, unfortunately, markedly higher in the 2000s than in the 1990s. The increased numbers of civilian personnel in the field might explain this. Nevertheless, similar to uniformed personnel, there is no trend towards an increase in the relative numbers of fatalities among civilians. Figure 3 shows the number of fatalities per 1000 civilian personnel in UN peace operations between 2005 and 2014. In this 10-year period fatalities per 1000 civilian personnel actually decreased by more than 50 per cent, from 1.94 to 0.85 per 1000. Meanwhile, the number of civilians who died due to malicious acts remained stable at 0.1–0.2 per 1000.

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 3. Fatalities per 1000 civilian personnel in United Nations peace operations, 2005–14.

Notes: See box 1 for details of the methodology.

Source: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO).

Trends in Fatalities by Peacekeeping Operation

Fatalities are not evenly spread across peace operations, and those with particularly high personnel losses can significantly influence annual fatality levels. For example, the huge spike in fatalities in 1993 resulted primarily from the high number of losses suffered by UNPROFOR, UNTAC and UNOSOM II. An obvious explanation for the differences in fatalities is that UN peace operations vary in terms of operational environments, strength and composition, and mandated tasks. For instance, operations deployed amid ongoing conflict face larger threats than ‘traditional’ ceasefire observation missions, while operations with robust mandates are often assumed to involve more combat and consequently suffer more hostile deaths, particularly when they are authorized to use force against so-called spoilers.[6] As several current peacekeeping operations fit both categories, the assumption would be that this is reflected in their fatality figures.

Click image to enlarge.

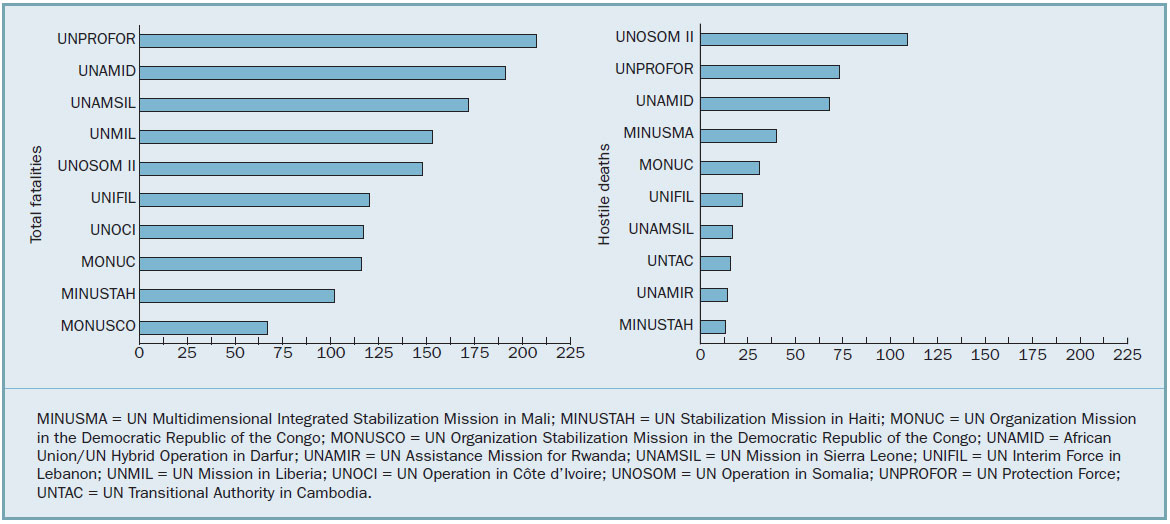

Figure 4. United Nations peacekeeping operations with highest absolute numbers of fatalities and hostile deaths among uniformed personnel, 1990–2015.

Notes: Figures are as of 2 July 2015.

Source: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO).

Yet the data at the mission level reveals a more nuanced picture. Focusing on uniformed personnel in UN peacekeeping operations since 1990—political and peacebuilding missions are excluded because their military and police deployments are negligible—Figure 4 shows the 10 operations with the most fatalities and hostile deaths (in absolute terms). UNPROFOR had the highest absolute number of fatalities, followed by 7 operations in Africa, as well as UNIFIL (Lebanon) and MINUSTAH, the latter of which lost most of its personnel in the 2010 Haiti earthquake. UNOSOM II suffered the most fatalities in terms of hostile deaths, followed at some distance by UNPROFOR and UNAMID (Darfur). MINUSMA, which began only two years ago in 2013, is in fourth position. Besides UNAMID, MINUSMA and UNIFIL, none of the other currently active operations is among the top 10 in terms of hostile deaths.

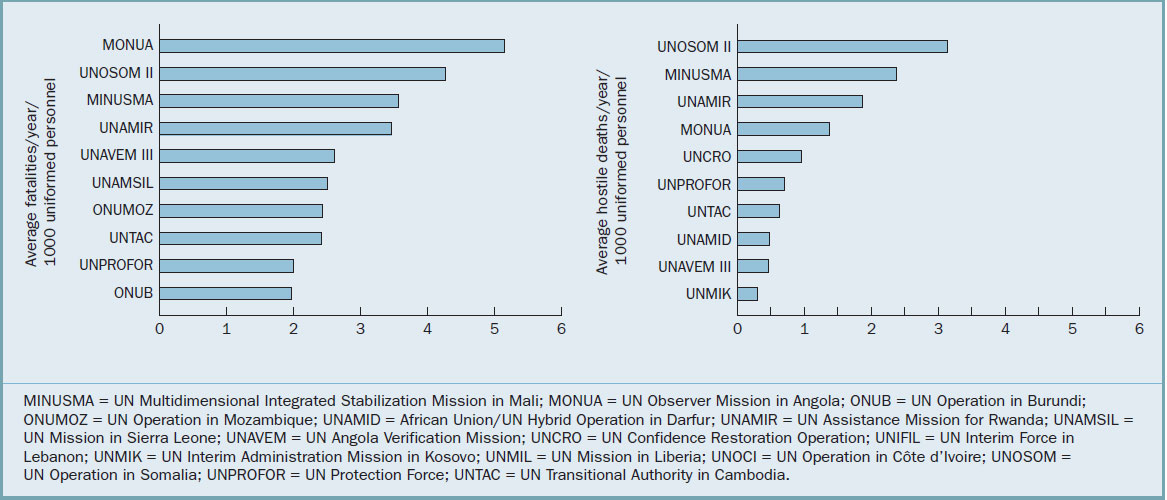

The top 10 looks quite different when mission strength and duration are taken into account. Figure 5 shows the 10 peacekeeping operations that suffered most fatalities and hostile deaths per year and per 1000 uniformed personnel (relative fatalities/hostile deaths).

Click image to enlarge.

Figure 5. United Nations peacekeeping operations with highest relative numbers of fatalities and hostile deaths among uniformed personnel, 1990–2015.

Notes: Figures are as of 2 July 2015. Calculations exclude peacekeeping operations with fewer than 1000 uniformed personnel on average.

Source: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO).

As fatalities in small operations easily result in high relative values, operations that deployed fewer than 1000 uniformed personnel on average per month are excluded in these figures (but can be found in table 1). MONUA (Angola) had the highest relative number of fatalities, followed mostly by operations that were active in the 1990s. In fact, except for MINUSMA (discussed below), the only other operations in the top 10 in terms of the relative number of fatalities that were active in the 2000s are UNAMSIL (Sierra Leone) and ONUB (Burundi), which ended in 2005 and 2006 respectively. UNOSOM II accounted for the highest relative number of hostile deaths. MINUSMA, UNAMID and UNMIK (Kosovo) are the only ongoing peacekeeping operations in the top 10, although it should be noted that UNMIK has not suffered a single fatality among its uniformed personnel since 2008.

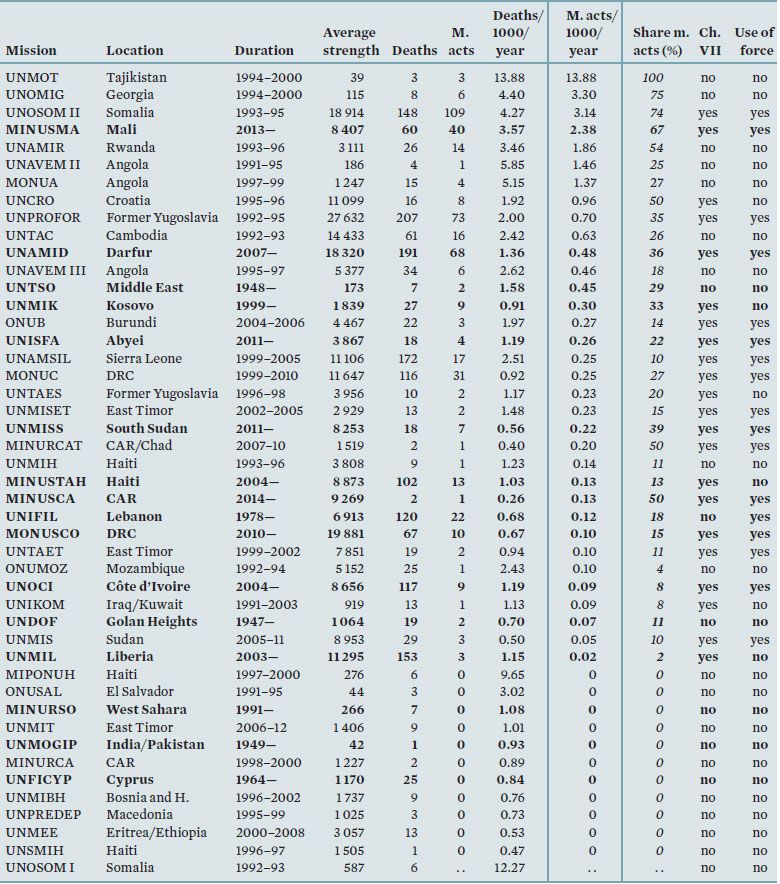

Table 1 shows that, in general, most ongoing UN peacekeeping operations have not experienced unusually high relative numbers of hostile deaths. The table provides a complete overview of all operations since 1990 (including the smaller operations) and ranks them according to the relative numbers of hostile deaths. With the notable exception of MINUSMA, all other ongoing operations rank in the bottom third of fewest relative hostile deaths figures. By contrast, out of the 10 most deadly operations in terms of relative numbers of hostile deaths, 9 were active during the 1990s.

Click image to enlarge.

*CAR = Central African Republic; Ch. = Chapter; DRC = Democratic Republic of the Congo; H. = Herzegovina; M. = malicious; . . = data not available.

Table 1. Fatalities among uniformed personnel in United Nations peacekeeping operations, 1990–2015.

Notes: Figures are as of 2 July 2015. Missions are ranked according to their value of relative malicious acts (average per year per 1000). Ongoing peacekeeping operations are in bold. UNTAG (1989–90) is excluded because its deployment ended in March 1990.

See box 1 [in the full report] for details of the methodology.

Source: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO).

Contemporary UN peacekeeping operations: more robust, fewer fatalities?

The data shows that there is no clear relation between the ‘robustness’ of mandates and the relative number of hostile deaths.[7] Only four peacekeeping operations in the top 10 of operations with the highest relative number of hostile deaths had or have Chapter VII mandates under the Charter of the United Nations, three of which had or have the explicit authority to use force beyond self-defence.

Most peacekeeping operations that received increased robust mandates in the past decade or so have on average not suffered unusually high relative fatality figures in terms of hostile deaths. Particularly surprising is the low position of MONUSCO (Democratic Republic of the Congo), which—with its Force Intervention Brigade and mandate to neutralize armed groups—is arguably one of the most robust UN peacekeeping operations ever established. The same applies to MINUSCA and UNMISS, which operate in hostile environments in CAR and South Sudan, respectively (although it might be too soon to draw conclusions on the former given the short time it has been in place).

MINUSMA: the exception that proves the rule?

MINUSMA has dominated the fatality count in UN peacekeeping operations in the past two years. It has already lost 60 uniformed personnel so far, of which 40 were hostile deaths.[8] In 2014 MINUSMA accounted for 80 per cent of all UN peacekeepers who died of such causes (28 of 35). Since 1990 only UNOSOM II suffered more hostile deaths in a single year (81 in 1993). Many peacekeepers that have been killed in Mali died in several multi-casualty incidents, often involving improvised road bombs or targeted attacks. These types of asymmetric attacks against UN peacekeepers are a relatively novel development, and the experience of MINUSMA underscores that the UN has found it difficult to adapt to these new kinds of threats.[9]

Table 1 shows that MINUSMA is indeed one of the most deadly operations in the history of UN peacekeeping. Only three operations have had a higher average number of hostile deaths. Disregarding operations with an average of fewer than 1000 uniformed personnel, only UNOSOM II ranks higher. The differences when compared to other current operations are striking.

MINUSMA is therefore clearly an exception rather than representative for of current UN peacekeeping operations. Thus, while UN Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping, Hervé Ladsous, recently stated that MINUSMA’s casualty level is ‘quite revealing of modern-day peacekeeping’, this is simply not correct—neither in absolute nor in relative terms.[10]

Conclusions

It is evident that many UN peacekeepers operate in highly challenging and dangerous environments. However, contrary to what seems to be commonly assumed, the absolute and relative numbers of fatalities in UN peacekeeping operations have not increased significantly over the years. In fact, the trend in the relative number of fatalities between 1990 and 2015 seems to suggest the opposite. Similarly, most ongoing peacekeeping operations suffer comparatively few fatalities (whether hostile or not hostile deaths), despite their increasingly robust mandates. A notable exception is MINUSMA, which is, in fact, one of the most deadly UN peacekeeping operations ever.

There are several possible explanations for why this long-term relative decline in fatalities has, for the most part, gone unnoticed. First, as decision makers and the general public are consumed by day-to-day business, they may lack the long-term memory or interest to place current affairs into their historical perspective. Second, in today’s ‘Twitter era’ casualties and incidents have become more visible. Whereas in earlier times news about fatalities might have gone unnoticed, today such news can reach a global audience in an instant. Third, major troop-contributing countries (TCCs) may be using the argument that peacekeeping has become an increasingly risky endeavour in their lobbying to boost troop reimbursements. Fourth, proponents of more funding for peacekeeping operations may be using such arguments to legitimize increased spending, while those who advocate budget cuts are perhaps using them to illustrate the UN’s ineffectiveness.

While the number of fatalities occurring during UN peacekeeping operations does not appear to be increasing, it may still be true that peacekeeping environments have become more dangerous. If that is the case the findings of this brief suggest that, since the 1990s, the UN has improved markedly in managing the threats against its personnel in the field. However, a more concerning possibility is that UN peacekeeping operations and TCCs have become more risk averse and, in order to minimize casualties, avoid confrontations with armed groups at the expense of implementing their mandate. [11] The High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations noted in its final report that peacekeeping operations mandated to protect civilians sometimes ‘struggle simply to protect and resupply themselves’, and that ‘in increasingly dangerous environments [they are] often reduced to delivering a limited set of critical tasks’.[12]

Policy implications

The findings in this policy brief have the following policy implications:

1. The UN needs to better highlight its achievements: Despite significant challenges and occasional setbacks, the fact remains that the UN is deploying more peace operations personnel than ever. Alarmist rhetoric about fatalities is not helpful at a time when renewed confidence in peace operations is required, especially if such rhetoric is based on false assumptions.

2. As UN peace operations fatality figures seem to be improving, this could be another incentive for Western countries to participate in such operations: The UN is in dire need of niche capabilities and force enablers that current TCCs cannot provide. Western countries, which are better positioned to provide these capabilities, tend to give insufficient force protection and security measures as the main reasons for non-participation. However, their experiences with UN peacekeeping in the 1990s may no longer be relevant to active peace operations. While such operations are taking place under equally (if not more) difficult circumstances, fatality rates actually appear to be falling.

3. Every fatality needs to be prevented, not only those caused by malicious acts: Most fatalities still result from non-hostile causes. More can—and should—be done to minimize deaths resulting from illness and accidents.

4. Peacekeepers deserve the best training, equipment and capabilities for self-protection: The experiences of MINUSMA in Mali underline that peacekeepers facing asymmetric threats require modern equipment, technology, tools and training methods in order to protect themselves against ambushes, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), landmines, mortar strikes and suicide attacks.

5. Force protection cannot be the overall goal of UN peacekeeping operations: Although the aim should be to minimize fatalities, this should not absorb the whole operation at the expense of mandate implementation. For the credibility of the UN as a security provider it is imperative that operations perform the tasks assigned to them, such as the protection of civilians.

Notes[1] Ban, K., Secretary-General to the United Nations, ‘Secretary-General remarks at wreath-laying ceremony for International Day of United Nations Peacekeepers’, 29 May 2015, external pagehttp://www.un.org/sg/statements/index.asp?nid=8687call_made.

[2] United Nations, Security Council, 7275th meeting, S/PV.7275, 9 Oct. 2014.

[3] United Nations, ‘Report of the High-Level Independent Panel on United Nations Peace Operations’, A/70/95-S/2015/446, 17 June 2015.

[4] United Nations, A/70/95-S/2015/446 (note 3), p. 89.

[5] See box 1 for details about the sources used for this policy brief.

[6] Bellamy, A. J., ‘Are new robust mandates putting UN peacekeepers more at risk?’, IPI Global Observatory, 29 May 2014, external pagehttp://theglobalobservatory.org/2014/05/newrobust-mandates-putting-un-peacekeepersat-risk/call_made.

[7] Bellamy (note 6) has drawn similar conclusions based on the proportion of fatalities caused by malicious acts per year for all UN peacekeeping operations combined.

[8] As of 2 July 2015.

[9] Between June and Nov. 2014 alone, 25 UN peacekeepers were killed in Mali in 5 single multi-casualty attacks. United Nations, Security Council, ‘Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Mali’, S/2014/692, 22 Sep. 2014 and S/2014/943, 23 Dec. 2014.

[10] United Nations, Security Council, 7464th meeting, S/PV.7464, 17 June 2015.

[11] A 2014 report by the UN Office of Internal Oversight Service names the unwillingness of TCCs to accept the risks involved with the use of force as one of the reasons why many peacekeeping operations are hesitant to use force to protect civilians, despite their authorization to do so. United Nations, General Assembly, ‘Evaluation of the implementation of and results of protection of civilians mandates in United Nations peacekeeping operations’, Report of the Office of Internal Oversight Service, A/68/787, 7 Mar. 2014.

[12] United Nations, A/70/95-S/2015/446 (note 3) p. 22, p. 38.