Gender Balancing in CSDP Missions

10 Dec 2015

By Maline Meiske for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Union Institute for Security Studiescall_made on November 2015.

In October 2015, the UN Security Council con - ducted a High-Level Review aiming at assessing progress in the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on women, peace and security. The Review provides an opportunity to take a closer look at the developments and progress made in the context of the CSDP. Ensuring women’s participation in CSDP crisis management operations is still a major challenge, particularly in military operations. Endeavours at the EU-level alone, however, are insufficient, and can only succeed in conjunction with member states’ efforts.

The EU has increasingly recognised that conflict and crisis management are not gender-neutral af - fairs and has introduced numerous gender policies and initiatives to forward the aims of UNSCR 1325. The key phrase is ‘gender mainstreaming’ – the process of assessing the implications of any planned action for men and women, which includes the proportional representation of both genders in conflict resolution and crisis management operations (also referred to as ‘gender balancing’). Boosting women’s participation began as an equal rights issue, but it has developed into a functionalist argument about improved operational effectiveness of crisis management and sustain - ability of conflict resolution. Adequate representation of female personnel is thought to help com - bat sexual violence, promote gender awareness among the host nations’ populations, and improve relationships between peacekeepers and local citizens. With the gradual release of gender-disaggregated data on women’s participation in crisis management operations, research on gender balance and the impact on operational effectiveness is on the rise. EEAS data on 16 civilian CSDP missions be - tween 2007 and 2013 reveal an increase in women’s participation, suggesting that gender policies and initiatives have had some success. Overall, the proportion of women participating in civilian CSDP missions rose from 20% to 26% and the absolute number of female civilian personnel in - creased from 240 to 869. For CSDP military operations, no gender disaggregated data is retained – a shortcoming that is in the process of being addressed. The EU Military Staff, however, estimates that only 3%-8% of the deployed personnel in CSDP military operations are female.

Mind the gap

To understand why women remain underrepresented in CSDP missions and operations, the methods of recruitment must be examined. Personnel are mainly supplied through national secondments, meaning that the decision-making authority in the allocation process lies with each member state. The underlying characteristics of each state thus determine women’s participation in CSDP missions. That there is a higher proportion of women in national civilian crisis management forces than in the military is reflected at the EU level. In 2013, for example, female police officers accounted for 16% of the total number in EU member states, whereas the percentage of women in national armed forces stood at 9%.

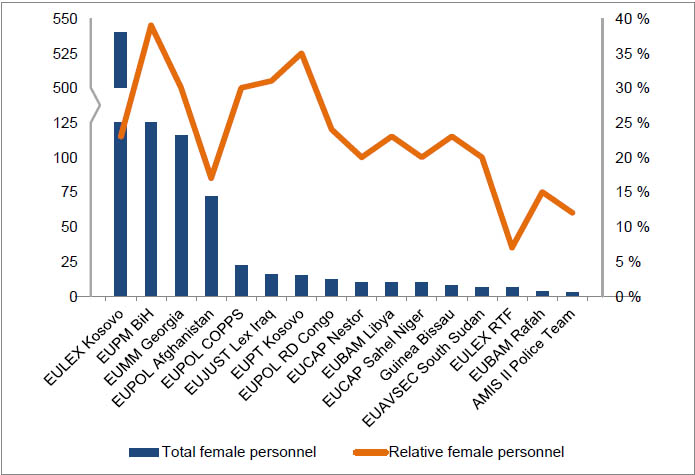

Absolute numbers and percentages of women deployed in individual civilian CSDP missions (2007-2013 averages)

Additionally, it should be noted that within military missions, only a minority of the female personnel assume a ‘direct combat role’, and instead are most strongly represented in support roles like logistics or administration. Moreover, women with direct combat roles are dispersed unevenly inside military organisations and constitute only a very small number of senior officers. Of the EU Military Staff currently stationed in Brussels, for instance, only 16 (8.5%) are women, the majority of whom are assistants. Likewise, no woman has ever hold the position as Head of Mission of an EU military operation and the first woman to head a civilian EU crisis management mission was only appointed this year – Pia Stjernvall for EUPOL Afghanistan. But just because a mission is civilian in nature does not mean that it automatically boasts a better gender balance. While EULEX Kosovo, for ex - ample, deployed on average 540 (23%) women and EUPM Bosnia and Herzegovina 125 (39%), EUPOL Afghanistan saw on only 71 (17%) employed. The variability in the proportion of female personnel in different missions is thought to be related to the conflict intensity in the area of deployment, but more concrete explanations are still needed. It is often assumed that gender balance is easier to attain than gender mainstreaming. However, while the EU can provide many guidelines, achieving gender balance on the national level is a prerequisite for ensuring gender balance in CSDP missions and operations.

Moreover, though gender-disaggregated statistics may function as an indicator for assessing the progress in terms of gender balance, simply ‘counting women’ cannot capture the complexity of women’s participation. It cannot explain the reasons for their consistent underrepresentation, their actual impact on the success and effectiveness of crisis management operations, or the different roles they play in the armed forces. Policies to improve gender balance in both the civilian and military aspects of crisis management have to take all these complex realities into ac - count, too. After all, gender balancing is not just a matter of ‘add women and stir’.