LAC's Insecure Economies

5 Feb 2016

By José Luengo-Cabrera for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 21 January 2016.

With falling commodity prices, slowing Chinese growth and tightening financial conditions, the economies of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) have once again revealed their vulnerability to global headwinds – albeit to varying degrees. Dragged down by the faltering economies of Brazil, Argentina and Venezuela, the region has been experiencing economic deceleration for the past five years, with 2015 marking the first of overall regional contraction since 2009.

This comes at a time when popular disgruntlement with political leaders has been rekindled as a result of macroeconomic mismanagement, high-level corruption and widespread urban insecurity. Amid looming policy paralysis, the outlook for the major LAC economies is bleak.

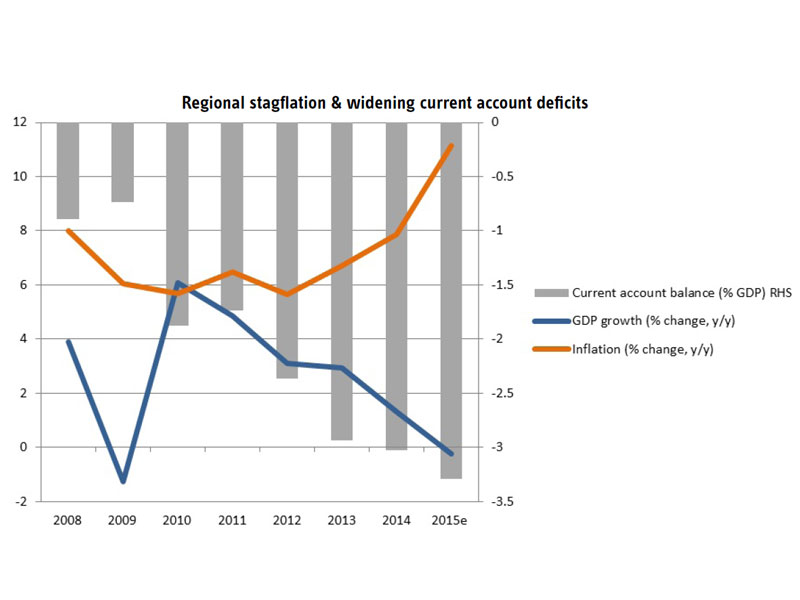

With double-digit inflation averaging across the region, the weakening of major currencies will continue to exert upward pressure on consumer prices, particularly through rising import costs exacerbated by an appreciating US dollar. The return of stagflation bodes ill for political stability, as opposition-led protests are already resurging. Amid growing levels of unemployment, the urge to adopt austerity measures is already clashing with workers’ demands for higher wages.

Water recedes, rocks appear

The adverse global conditions have shed light on the structural weaknesses of LAC economies. Having largely benefited from the 2000s commodities ‘super-cycle’, region-wide fiscal profligacy took root. But with the recent fall in energy, metals and agricultural prices, foreign-exchange reserves have shrunk drastically. This has reduced the buffers needed to weather the storm generated by global markets – as evidenced by widening current account deficits.

Brazil and Venezuela stand out as the worst regional performers. Their high dependence on Chinese demand and heavy reliance on oil has prompted a sharp fall in government revenue. This has been particularly true for Venezuela, as 45% of its budget proceeds and 96% of its export earnings depend on the sale of cheapened crude. And populist government spending ahead of the recent legislative elections has only deepened the state’s budget deficit further. Although the opposition Democratic Unity platform now has a supermajority in Congress, its internal divisions may delay efforts to propose much-needed fiscal consolidation plans. In turn, President Maduro’s eagerness to cling to power may undermine political stability as social unrest could intensify in the event of prolonged political wrangling, especially amid rampant inflation (141% y/y) and protracted shortages of consumer goods. The recently announced emergency decree, should it be implemented, is unlikely to avert a full-blown economic collapse.

In Brazil, a political crisis has erupted following a congressional impeachment process against President Rousseff – relating to a corruption scandal involving top-level politicians. Consequently, a political gridlock has halted the administration’s push to implement spending cuts and the looming policy paralysis has damaged investor confidence. But with faltering approval ratings, the government might still be tempted to implement populist (i.e. loose) fiscal and monetary policies; measures which could prove counterproductive for an already overheated economy. Driven by rising food and transport prices, inflation rates are at a 12-year high (10.5%), and widespread anti-government protests calling for Rousseff’s resignation already erupted last December and in early January 2016.

Source: IMF (WEO,2015). Note: average of aggregate data for LAC cohort. GDP in constant prices. Inflation = average consumer prices (click to enlarge).

Political cost of adjustment

While Brazil and Venezuela are facing the highest political costs in rebalancing their economies, Argentina stands out as a country where high expectations raised by the recent presidential elections could be reversed. Burdened by high debt payments and faltering trade with neighbouring Brazil, Argentina’s economy has been suffering the consequences of the protectionist policies of the Kirchner administration(s). Thus far, the newly-elected Macri government has rapidly implemented much-needed reforms, with export tariffs on major agricultural products either scrapped or partially removed. In tandem to the lifting of currency controls, a fresh round of negotiations was launched with the country’s holdout creditors, raising hopes of restoring its access to international financial markets.

However, with entrenched inflation problems, prohibitive interest rates (38%) and GDP growth below 1%, Argentina’s path to economic recovery remains uncertain. Possible clashes with trade unions demanding wage rises could result in labour unrest as the high cost of living continues to erode workers’ purchasing power.

Silver linings?

By contrast, Mexico, Chile, Peru and the net oil importers of the Caribbean have been able to partially absorb the global shockwaves. Mexico, for example, is benefiting largely from its economic integration with the US, with the latter’s economic recovery boosting the central American country’s industrial exports. Drug-related violence remains widespread, however, and may intensify with reprisals against security forces and government officials in the wake of the recent arrest of the infamous drug kingpin ‘El Chapo’.

In turn, Colombia’s economic outlook is set to improve thanks to the prospects of political stabilisation. The government reached a partial agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) over reparations and special tribunals last September, and a full peace deal could finally be struck this coming March. Although costly in the short term, a lasting peace agreement would yield significant economic dividends. Indeed, post-conflict experiences in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala demonstrate the opportunities for economic expansion which result from lower security-related spending, falling homicide rates and improved productivity.