European Defence: The Year Ahead

7 Feb 2017

By Daniel Fiott for European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)

This article was external pageoriginally publishedcall_made by the external pageEuropean Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS)call_made on 31 January 2017.

After several months of intense work, the European Union ended 2016 having agreed to a number of fresh initiatives designed to articulate (and act on) a new level of ambition for security and defence. Under the overall direction laid down by the EU Global Strategy (EUGS), a specific plan on security and defence (SDIP) was published on 14 November 2016 – elements of which were endorsed at the Foreign Affairs Council on the same day and the 15 December 2016 European Council. Additionally, the European Commission published a European Defence Action Plan (EDAP) on 30 November 2016, and the EU and NATO agreed to act on the Joint Declaration they had signed at the Warsaw Summit in July by adopting conclusions for 42 action points on 6 December 2016. The EU therefore starts 2017 with a range of policy options to enhance defence cooperation: aligning these initiatives to produce coherent policy in the future is now a priority.

While 2018 could allow more political room for manoeuvre (following the string of elections scheduled in a number of key member states) for the agreed initiatives to take root, a small window of opportunity currently remains which will likely close at the end of March 2017 – in time for the 60th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome. After this point, negotiations with the UK on its expected departure from the EU are likely to begin, and a number of European governments will head into election mode. Within such a window, therefore, it may be worth reflecting on how the various initiatives tabled towards the end of 2016 could fit together and/or complement one another. This is an especially pertinent exercise given that some of the ideas that were around before 2016 – such as Permanent Structured Cooperation (PeSCo) – are once again being held up as potential game changers in the way EU member states cooperate on security and defence.

Recap and review

Following the June 2016 publication of the EUGS, eyes immediately turned to implementing its various work strands. Most prominently, a specific plan on security and defence was drafted and delivered on 14 November by High Representative/Vice-President (HR/VP) Federica Mogherini. The SDIP articulated a number of initiatives, including the suggestion for a voluntary Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) that would assist member states to better synchronise their defence planning through a yearly review to be conducted by the European Defence Agency (EDA). The Foreign Affairs Council also specifically requested proposals on strategic-level planning and oversight of operations, with a particular emphasis on civ-mil synergies, to compliment the establishment of an EU ‘permanent operational planning and conduct capability’ for non-executive CSDP missions.

The SDIP contains thirteen action points that articulate a new level of ambition on security and defence for the EU, and, above all, it introduces the innovative concept of ‘protecting the Union and its citizens’ – i.e. tackling those security challenges that fall along the nexus of internal and external security. In addition to wanting to respond more effectively to external conflicts and crises and build the capacity of partners, the SDIP built on the EU Global Strategy’s promotion of the interests of European citizens. Both the Council of the EU and the European Council endorsed the need to ‘protect Europe’ and take forward a number of specific policy proposals including the need to reframe the spectrum of crisis management tasks (to include, for example, special, air and maritime security operations and ‘hybrid’ threats) undertaken by the EU. Time will tell if these new tasks materialise into an identification of related military capability needs and shortfalls.

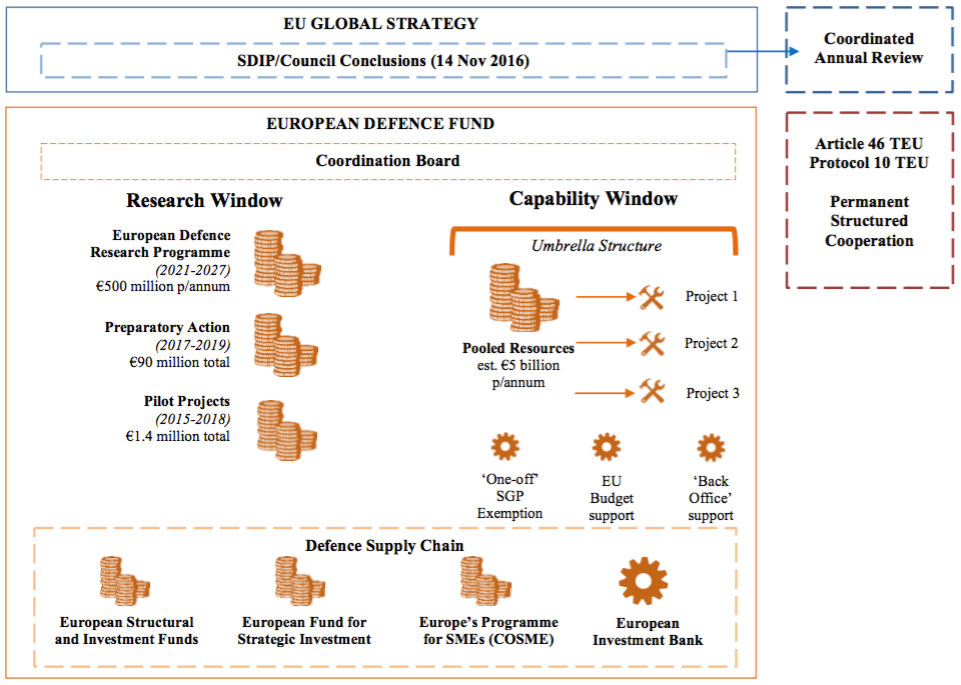

To add to these initiatives, the European Commission released the EDAP on 30 November 2016. This plan focuses on the industrial and capability development elements of EU cooperation and articulates the new idea of a ‘European Defence Fund’ (EDF). This fund is comprised of two individual but interlinked ‘windows’ related to defence research and capability development:

- a ‘research window’ in the fund focuses on the way the European Commission can support defence research, and to this end EU funds are being made available to support defence-relevant small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and research institutes. From March 2017 to 2020, for example, the EU will allocate €90 million for defence research. The hope is that a specific European Defence Research Programme worth an estimated €500 million per year will come into play after 2020.

- a ‘capability window’ will pool national resources for the purposes of joint capability development (such as strategic enablers). The Commission estimates that the ‘capability window’ could amount to up to €5 billion per year. To encourage member states to engage with the window, the Commission is offering incentives in the form of a) a ‘one-off’ exemption for national capital contributions to the fund from the Stability and Growth Pact rules on deficits; b) ‘back office’ support for the projects and potential coverage of the administrative costs of the ‘capability window’ under the EU budget; c) possible use of the EU budget to support demonstrator projects, prototypes, feasibility studies and testing. To manage such projects, an ‘umbrella structure’ will be established to set out the framework for cooperation and to outline the European Commission’s level of support.

To more broadly underpin the European Defence Fund, and to ensure a more effective defence supply chain in Europe, the EDAP also foresees a more significant role for the European Investment Bank in supporting SMEs. In this vein, the EDAP outlines areas of support for the defence supply chain and SMEs with financial instruments such as the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) and the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF).

On top of that, the European Commission spent much of 2016 evaluating the effectiveness and relevance of two directives adopted back in 2009 to enhance cross-border transfers of defence equipment (2009/43/ EC) and provide clarity over defence procurement (2009/81/EC). The conclusion is that investments alone are not enough to support the European Defence Technological and Industrial Base; a harmonised approach to internal trade in defence equipment and defence procurement in the defence sector is still required.

Finally, the EU and NATO then agreed to act on the Joint Declaration they had signed at the Warsaw Summit in July by adopting conclusions on 6 December 2016. These laid down more than forty action points in seven different areas (‘hybrid’ threats, operational cooperation, cyber security, defence capabilities, industry and research, exercises and capacity building) that are designed to take forward the cooperation between the Union and the alliance. A report detailing the progress being made on EU-NATO cooperation will be delivered by the end of June 2017.

EU defence policy ‘eco-system’ (2016-17)

Enter PeSCo

Many of the initiatives adopted in 2016 could complement the work being undertaken by the HR/VP to provide ‘elements and options’ for PeSCo under Article 46 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU).

Interestingly, many of the initiatives brought about by the EDAP (i.e. the defence fund, the capability window and the umbrella structure) and the SDIP’s suggestion for a Coordinated Annual Review on Defence are not mutually exclusive with PeSCo. It could even be said that the European Defence Fund actually provides a greater level of clarity over the scope and purpose of European defence cooperation than was the case with the PeSCo provisions (under both Article 46 and Protocol 10).

Whereas PeSCo never sought to pre-judge the specific shape of permanent structured cooperation on defence, the EDF – and in particular its ‘capability window’ – is clearly geared to defence capability development. The Commission even goes as far as to estimate the basic financial contribution that would be required to launch joint capability programmes. The specific rudiments of PeSCo were never as clear.

Critics of PeSCo argue that there is little point in triggering Article 46 when EU member states can already do more together. The publication of the EDAP and the idea for a CARD could be viewed as exemplary areas where greater cooperation can be achieved without a need to necessarily invoke treaty articles. Nevertheless, the feeling of several member states is that triggering PeSCo would inject stronger political commitment into European defence. It is worth recalling that PeSCo is written into the EU treaties (albeit as an enabling provision, not an obligation) and that it would therefore be legally binding on those EU member states that decide to trigger Article 46 through qualified majority voting – although it would have to be inclusive from the start and not exclude any member states that may want to join in the future.

Before an inclusive PeSCo is initiated, however, there needs to be consensus on the criteria guiding such cooperation: if there is no preliminary agreement on the purpose and shape of PeSCo, it is unlikely that it would deliver on the aspiration for closer defence cooperation. The political expectations associated with PeSCo are indeed such now that member states would not likely risk initiating it without some guarantee that it would be lasting, meaningful and mutually reassuring. On the other hand, given that the debate on PeSCo has now officially started, it might become politically awkward not triggering it.

A Coordinated Annual Review on Defence inside PeSCo could provide a way to ensure commitments on defence expenditure and investments, standardisation and interoperability, and coordinated defence procurement by making them more binding in nature. As it stands, in fact, the CARD is viewed as a voluntary mechanism to enhance the synchronisation of member state defence planning – all under the auspices of the EDA. Should it stand outside PeSCo, it would definitely require sustained political commitment from the member states.

Proponents of PeSCo also state that it would need to be internally modulated so as to allow individual capability programmes to be placed within it. Internal modulation of PeSCo would also lend the requisite flexibility to those member states that wish to pursue closer collaboration in specific capability areas. This flexibility also informs the European Commission’s idea for a ‘capability window’ under the European Defence Fund.

Here, a question would be whether some coherence between the capability projects initiated under PeSCo and the EDF’s ‘capability window’ could be achieved. One possible way of ensuring complementarity and even synergy would be to place the European Defence Fund inside PeSCo, too. This would, however, entail coming to some agreement on how EU funds (to which all member states contribute) could be used for only some projects and member states under the ‘capability window’ and/or PeSCo.

In this regard, the Commission’s idea to form an ‘umbrella structure’ to manage various capability development programmes could also be seen as a way to ensure coherence over the ways in which PeSCo could be internally modulated. If so, then how would the ‘umbrella structure’ and the Coordinated Annual Review on Defence complement each other? Indeed, both initiatives aim to instil some degree of synchronicity in national defence planning and budgetary cycles.

PeSCo may well be seen as a mechanism through which to rationalise these various initiatives, although how an ‘umbrella structure plus CARD’ would be managed inside PeSCo remains to be seen. The HR/VP is likely to have a key role in this regard, although perhaps the ‘Coordination Board’ foreseen in the European Defence Fund – which will be composed of member states, HR/ VP, EDA, Commission and industry – could be a conceivable model of governance.

Point of arrival?

Despite these options, it is also worth contemplating what would happen if Article 46 TEU is not triggered in early 2017. The year ahead includes a number of important national elections, so it is not entirely guaranteed that any outgoing governments will be willing or able to bind the hands of incoming ones by launching PeSCo. It might appear more sensible to first make a success of the ‘capability window’ contained in the European Defence Fund. Simultaneously initiating PeSCo and launching the European Defence Fund could be a tall order, and a lot of political effort will be required to achieve swift consensus among the member states on both of these initiatives.

Perhaps the European Defence Fund – and more specifically the ‘capability window’ – could be seen as an important test case for a future PeSCo. In a way, any joint capability programmes launched under that ‘capability window’ could already lead to the ‘modular approach’ called for by the European Council on 15 December 2016 and come to represent a sound basis for PeSCo.

Although the pressure to move European defence to a new level of cooperation is strong, perhaps a step-by-step approach is also worth considering in order to build the consensus required for an inclusive and meaningful PeSCo. If member states do not feel ready to initiate PeSCo within the next few months, in other words, this should not be read as failure. Even without PeSCo, many of the new initiatives agreed to in 2016 offer the EU a number of innovative avenues – and solid building blocks – through which to move from vision to action.

About the Author

Daniel Fiott is the Security and Defence Editor at the EUISS.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.