Russian Analytical Digest No 208: Post-Soviet De Facto States

18 Oct 2017

By Carolina de Stefano and Benedikt Harzl for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The two articles featured here were originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 10 October 2017.

Three Years On, Russia Faces New Challenges In Crimea

By Carolina de Stefano

Abstract

Since its annexation in 2014, Crimea has been undergoing major internal changes. Having cut all contacts with the peninsula to avoid giving the slightest form of recognition to Russia’s annexation, the West has lost the ability to know what is happening on the ground. Moscow and the local authorities have been implementing measures toward the full Russification of the peninsula and started a massive program of economic reforms aimed at giving it a “new life.” However, after three years and in a context of international isolation, problems with the feasibility of these reforms have started to emerge.

Crimea: a Blind Spot in Europe

While events in Ukraine’s Donbas remain a core element of contention between Russia and the West, the Crimean peninsula is becoming a blind spot for European politics.

The dispute over its status has critically reduced outsiders’ ability to visit the region, leading to a dearth of information about what is going on there. First, the current authorities require a Russian visa to enter. This demand has proved unacceptable for many, and especially for international organizations, since applying for such a document would correspond to the de-facto recognition of Moscow’s annexation. For the same reason, researchers and scholars are often prevented by their own institutions from going there.

On their side, the Ukrainian authorities limit entry by requesting special permissions to go to Crimea1 and by considering passage through Russia a crime punishable with prison. Kyiv also explicitly discourages foreigners from visiting the peninsula.2

Most acutely, local authorities refused the establishment of international permanent monitoring missions, arguing that human rights are not being violated and denying the need for such missions.3

In this context, the de-facto government exploited this absence of external observers to restrain local NGOs and media that are critical of the annexation. This is mally re-register in accordance with Russian legislation.4

Over the last three years, the refusal to abide by these measures has been presented by the authorities as an “extremist” or “separatist” act and used to close dozens of media outlets, including Chernomorskaya Television and the Crimean Tatar broadcaster ATR.5

Nevertheless, information transmitted by local NGOs and personal accounts of people who fled Crimea after 2014 have allowed international organizations to publish detailed reports on the human rights situation in the region.6

All of these documents report pressures, discriminatory measures and criminal prosecutions against journalists, NGO activists and ethnic and religious minorities (especially Crimean Tatars) who expressed their opposition toward the new authorities. Some of them also documented the mistreatment and disappearance of several people.7

Forced Russian Citizenship and the Implications for Minorities

Above all, the requirement to acquire Russian citizenship leads to discrimination against part of the population and violates their basic rights. Since the annexation, Russian citizenship is a necessary condition for having access to all the basic social rights, including education, healthcare, the right to work, and retirement pensions.8

Due the lack of available information, it is difficult to precisely estimate the percentage of the population that voluntarily acquired the new citizenship, as well as to distinguish it from those who were somehow forced to do it. According to the last national census (dating back sixteen years ago), the Crimean population was composed in 2001 of 58.3 percent Russians, 24.3 percent Ukrainians and 12.1 percent Crimean Tatars.9 Overall 77 percent of respondents indicated Russian as their native language.10

The conditions in which the 2014 referendum was held and the unresolved debate over the actual figures of voters’ turnout makes it difficult to assess the effective popular support that the Russian authorities enjoy, even though polls conducted between 2014 and 2015 show that the majority of the population approved the annexation.11

In any case, the fact is that those who refuse to take Russian citizenship have to either live in discriminatory daily conditions or flee the country, as has been the case for thousands of Crimean Tatars in the last three years.

As of today, one of the main acts encroaching on the rights of the Crimean Tatars has been the April 2016 order that shut down the Tatars’s self-governing Council of the Mejiis, a legislative body that had overtly but peacefully opposed the annexation. There again, authorities claimed that the group was involved in “extremism.”12

At the same time, the de-facto government sought to promote the creation of NGOs and religious groups that recognize Russian rule. It is noteworthy that these groups do not exclude participants on the basis of ethnicity or religious affiliation. In this light, three Crimean Tatars ran as candidates of the United Russia party in past local elections and new organizations representing ethnic minorities have been established.13

These small inclusive measures are far from sufficient to guarantee minorities’ place and rights in the new Crimea, as the flight of two hundred thousand people (10 percent of the population) between March 2014 and July 2017 dramatically testifies.14 The exit of these refugees is structurally changing the composition of the Crimean population in ways that are likely to remain in place for the long term.

Together with the requirement to obtain Russian citizenship, the Russification of the population is being secured by the implementation of language and school laws. While current legislation recognizes Russian, Ukrainian and Tatar as the three official languages of the Republic of Crimea,15 each with equal status, many Ukrainian and Tatar schools and programs, in fact, have been shut down.16

2014–2017: an Optimistic Plan with a Complex Implementation

The policies of Russification are not the only way in which Russian and local authorities aim at integrating Crimea into the Russian Federation. Over the last three years, an ambitious, long-term developmental program is underway and the Russian government has provided huge subsidies to the peninsula.

The great majority of the reforms are based on the “Strategy for the socio-economic development of Crimea until 2030,”17 and on the “Federal targeted program (Federal'naya Tselevaya Programma, FTSP) for the socio-economic development of Crimea until 2020” which was approved in August 201418 and which officially amounted to 769.5 billion rubles at the beginning of 2017.19 The program envisions 350 new construction projects in Crimea, including schools and hospitals, by the end of 2020. It also foresees the construction of the Kerch bridge, expected to be completed by the end of 2018, which will link Crimea to the south-eastern coast of Russia.

The poor conditions and most of the dysfunctionalities that were inherited from the pre-annexation period, though, remain and in many cases have been worsening since 2014.

Some situations are impossible to resolve in the short term. Sevastopol, for example, has the lowest regional GDP in Russia—$1,500 per capita in 2015 compared to an average of $7,500 across Russia.20

Inflation climbed, peaking with a 25 increase in 2015,21 and the economic situation is far from improving. Among other factors, the main causes are the negative effects of economic sanctions and international isolation on tourism,22 restricted access to foreign imported products and financial credits, and the absence of public services previously provided by Ukraine, such as water and electricity.23 Finally, economic uncertainties also followed the change in the national currency from the Ukrainian Hryvnia to the Russian ruble.

Since the beginning of 2017, problems in implementing the program started to emerge. First, unsurprisingly, the costs and time needed are proving to be much greater than was expected initially. In September 2017, the Crimean authorities declared that expenses could rise by an additional 70 billion rubles.24

The delays are also due to the complex process of harmonizing Crimean legislation and regulations with Russian equivalents and the concrete management of the program.

Although thousands of Russian officials were sent to Crimea since 2014, Russia has also relied on local politicians (mainly former members of the Party of the Regions which had been headed by ex-Ukrainian President Yanukovich)25 and bureaucrats. Beyond credibility problems resulting from the slow implementation of reforms, coordination among local structures, as well as between the peninsula and the Russian ministries in Moscow, is proving difficult, costly and inefficient overall.

The current state of affairs was laid out in June 2017, when a report issued by the Russian Federation Accounts Chamber criticized the excessive number of highly paid functionaries responsible for the implementation of the plan and asked the Crimean authorities for clarifications.26 Soon after, the Russian Deputy Minister for Economic Development Sergey Nazarov admitted the existence of a series of problems that Moscow is facing, and identified the main causes as the lack of expertise and excessive haste in approving the plan in 2014.27

According to recent polls, the majority of Crimeans declare themselves satisfied with Russian management of the region, even if they recognize the complexities of the current situation.28

Nevertheless, the question of the feasibility of the reforms announced after the annexation remains a key issue for the development and the future of the peninsula.

Crimea, a Second Kaliningrad?

As of today, it seems that the Russian government has two main preferred solutions to deal with the emerging issues in reforming and transforming Crimea: the first is to subsidize those sectors that, according to the 2020 development strategy, were supposed to flourish autonomously by attracting private investments, above all in the tourism sector.29

The other is to downgrade Crimea as a top priority. Potentially Russia could remove funding required to guarantee social development in the long-term, including subsidies for schools and education. Instead, it would privilege initiatives that seek to boost international prestige and popular national pride. It is not by chance that the high-profile Kerch Bridge will link the peninsula to Russia by the end of 2018,30 while other projects will be delayed, or even abandoned.

This approach would also be in line with the general attitude of the Russian population towards Crimea, which emerged in a recent poll of the Levada center: while more than two thirds support the annexation and think that it brought to Russia more benefits than harm, 55 percent consider it unfair that structural reforms in the peninsula are being entirely financed by the federal budget31 (see also “Opinion Poll” below).

In the medium term, the risk is that Crimea will end up being a trophy to be displayed in a showcase, while at the same time becoming in fact a new (and isolated) Kaliningrad, Russia’s mismanaged exclave on the Baltic Sea.

Notes

1 For the text of the Ukrainian law regulating entry to Crimea: <http://mfa.gov.ua/en/news-feeds/foreign-offices-news/23095-law-of-ukraine-no-1207-vii-of-15-april-2014-on-securing-the-rights-and-freedoms-of-citizens-and-the-legal-regimeon-the-temporarily-occupied-territory-of-ukraine-with-changes-set-forth-by-the-law-no-1237-vii-of-6-may-2014>

2 “Kiev prigrosil belorusam sanktsyam za poezdki v Krym”, RBK, <http://www.rbc.ru/politics/02/08/2017/5981e4c39a7947818f79c351>, 2 August 2017.

3 The European Parliament’s Committee on Human Rights, The situation of national minorities in Crimea following its annexation by Russia, <http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/578003/EXPO_STU(2016)578003_EN.pdf>, April 2016, 12.

4 Amnesty International, “One Year On: Violations of the Rights of Freedom of Expression, Assembly and Association in Crimea, <https://amnesty.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Crimea_Briefing_formatted_final_and_formatted.pdf>, March 2015, 11.

5 Freedom House, Crimea profile, 2017, <https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2017/crimea>

6 See, among others, the reports by the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities, Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, as well as several Ukrainian NGOs, included the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union and the Center for Civil Liberties.

7 Helsinki Human Rights Union, “Tortured, disappeared, persecuted: Crimea is asking for justice,” <https://helsinki.org.ua/en/articles/tortured-disappeared-persecuted-crimea-is-asking-for-justice/>, 23 January 2017.

8 The European Parliament’s Committee on Human Rights, The situation of national minorities, cit.

9 <http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/nationality/>

10 <http://2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua/eng/results/general/language/ Crimea/>

11 See the results of the public opinion survey conducted by John O’Loughlin and Gerard Toal and administered by the Levada Center in December 2015: <https://www.opendemocracy. net/od-russia/john-o%25E2%2580%2599loughlin-gerard-toal/ crimean-conundrum>

12 Amnesty International, “Crimea: Rapidly Deteriorating Human Rights Situation in the International Blind Spot,” <http://www. refworld.org/docid/58cb9e824.html>, 17 March 2017.

13 For the list of the NGOs registered to the de-facto authorities as “cultural-national autonomies of Crimea,” see <http://gkmn. rk.gov.ru/rus/info.php?id=616539>

14 Ilan Berman, “How Russian Rule Has Changed Crimea,” Foreign Affairs, <https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/eastern-europe-caucasus/2017-07-13/how-russian-rule-has-changed-cri mea>, 13 July 2017.

15 <http://crimea.gov.ru/textdoc/ru/7/project/2-351.pdf>

16 ‘Narod, Opalennyi ‘Vesnoi’, Novaya Gazeta, <https://www. novayagazeta.ru/articles/2017/07/26/73245-narod-opalennyy-vesnoy>, 26 July 2017.

17 The text is avaiable at <http://minek.rk.gov.ru/file/File/ minek/2017/strategy/strategy-shortvers.pdf>

18 The program is at <http://fcp.economy.gov.ru/cgi-bin/cis/fcp.cgi/ Fcp/ViewFcp/View/2017/429>

19 “Krym poluchit bolee 54 mlrd rublei po FTSP razvitiya respubliki v 2017 godu,”, Tass, <http://tass.ru/ekonomika/3957057> 20 January 2017.

20 Fabrice Deprez, “The September 10th Gubernatorial Elections: What’s the deal?,” <https://bearmarketbrief.com/2017/09/05/ the-september-10th-gubernatorial-elections-whats-the-deal/>, 5 September 2017.

21 “Inflyatsya v Krymu prevysila 25% za god,” Vedomosti <https:// www.vedomosti.ru/economics/news/2016/02/10/628341- inflyatsiya-krimu>, 10 February 2016.

22 “A Krym snova nash!” Novaya Gazeta, <https://www.novay agazeta.ru/articles/2017/07/31/73293-a-krym-snova-nash>, 31 July 2017.

23 “Iskhodnyi material,” Novaya Gazeta, <https://www.novayagazeta.ru/articles/2017/03/08/71716-ishodnyy-material> 15 March 2017; “Krym snova ostalsya bez elektrichestva,” Lenta. ru, <https://lenta.ru/news/2017/07/28/no_light/> 29 July 2017.

24 “Raschody na krymskuyu FTSP uvelichatsya na 56–70 mlrd rublei,” Kommersant <https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/ 3402641?tw>, 5 September 2017.

25 David Szakonyi, “State Duma Elections in Crimea,” Russian Analytical Digest no. 203, 15 May 2017, 2.

26 “Krym i Sevastopol' zhivut ne po raskhodam,” Kommersant, <https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/3330069>, 20 June 2017; RBK, ‘Schetnaya palata obnaruzhila neeffektivnoe ispol'zovanie deneg v Krymu’ <http://www.rbc.ru/society/20/06/2017/ 594899539a7947564826e1fd> 20 June 2017.

27 “Minekonomiki soobshchilo ob otstaivanii v realizatsii FTSP Kryma i Sevastopol,” Kommersant, <https://www.kommersant. ru/doc/3386104>, 17 August 2017.

28 “Tri Goda s Rossii: kak Zhivetsya lyudyam v Krymu”, RBK, <http://www.rbc.ru/economics/16/03/2017/58c95b509a794 700d2ed237c>, 16 March 2017.

29 “Turoperatorov vnesut v byudzhet,” Kommersant, <https://www. kommersant.ru/doc/3384299>, 15 August 2017.

30 Joshua Yaffa, “Putin’s Shadow Cabinet and the Bridge to Crimea,” The New Yorker, <https://www.newyorker.com/maga zine/2017/05/29/putins-shadow-cabinet-and-the-bridge-to-cri mea>, 29 May 2017

About the Author

Carolina de Stefano is a PhD candidate at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies in Pisa and a visiting researcher at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

Opinion Poll

Russian Attitudes Towards the Annexation of Crimea and the Financing of Investments for the Development of Crimea

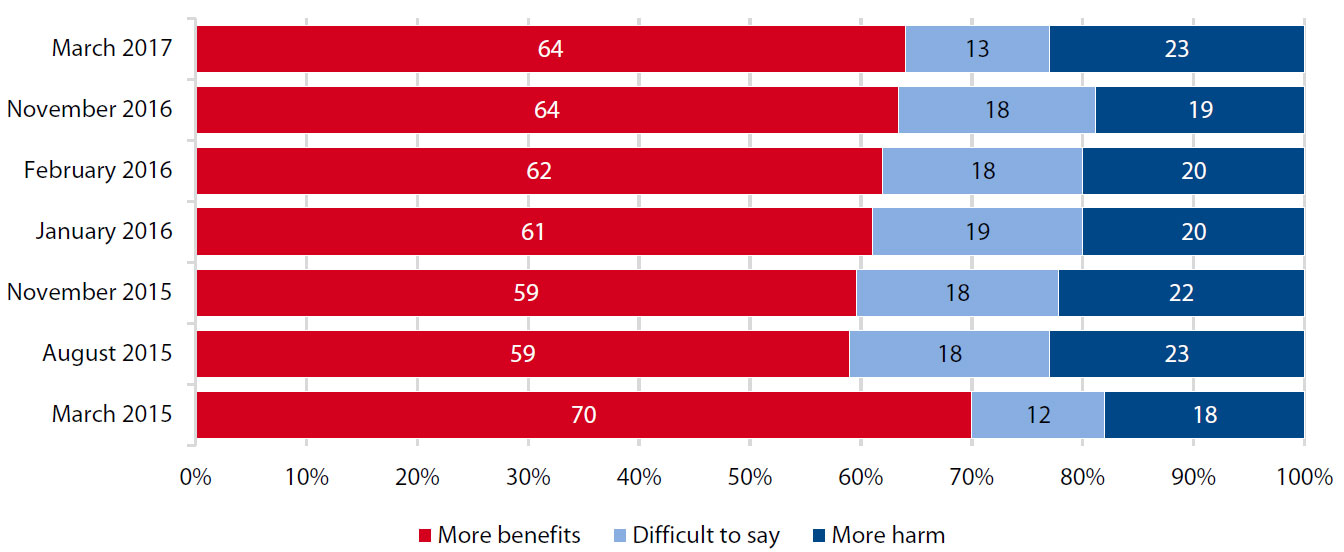

Figure 1: “On the Whole, Did the Incorporation of Crimea Bring More Benefits or More Harm to Russia?”

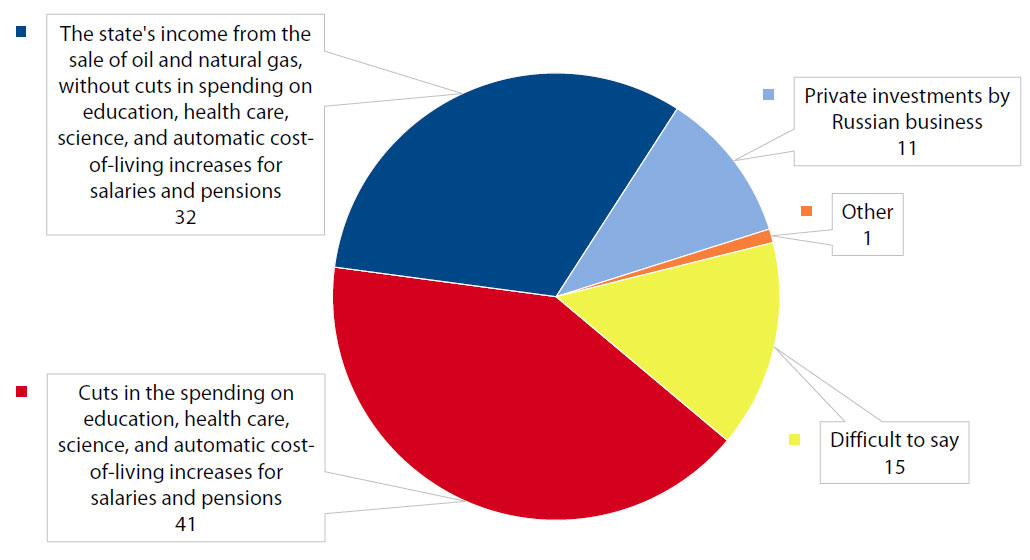

Figure 2: “The Incorporation of Crimea Required Significant Investments by Russia. In Your Opinion, What Are the Sources of Funds for These Investments?”

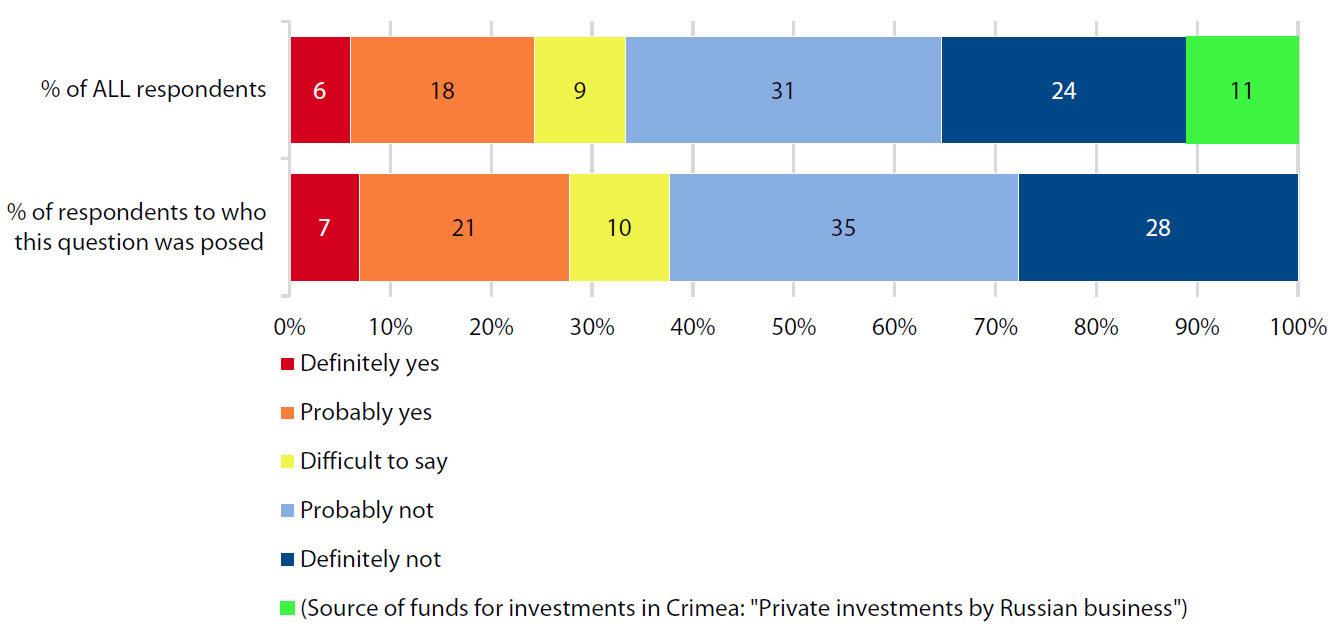

Figure 3: “What do you think—is the Russian government acting correctly by freeing budgetary resources for the development of Crimea, at the expense of cutting spending on education, health care, science, and automatic cost-of-living increases for salaries and pensions?” (question posed to respondents who chose answer “cuts in the spending on education, health care, science, and automatic cost-of-living increases for salaries and pensions” in the previous question)

Russia’s Approach to Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Problematic Legal and Normative Rationales for Citizenship and Bilateral Treaties

By Benedikt Harzl

Abstract

This article examines how Russia’s citizenship and bilateral treaties with the breakaway Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia have repercussions for elements of Russian domestic and foreign policies. Over time, Russia has changed its approach to dual citizens to reduce their rights to work within Russia and undermined its approach to Kosovo by recognizing secessionist regions in Georgia.

Three Factors Dictating the Triangle Dynamics of Russia, Georgia, and the Breakaway States

Although the current crisis in Ukraine, as well as the flare-up of violence over Nagorno-Karabakh in April 2016, often overshadow events surrounding Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the prevailing issues in the dynamics among Russia, Georgia and these breakaway regions continue to drive important parts of the narrative in the South Caucasus.

First, Russia and Georgia remain divided over the most basic question about the nature of the conflicts over these two entities and potential solutions. While Russia took the controversial decision to recognize both Abkhazia and South Ossetia as independent states in August 2008, the Tbilisi government—even after the somewhat Russia-friendlier Georgian Dream movement came to power—still insists on the principle of territorial integrity and regards these areas as part of Georgia. The divergence of these positions is unambiguous and will continue to remain so.

Following the 2008 fighting, the Georgian authorities have abandoned force as a means to reestablish jurisdiction over the breakaway states. Likewise, the outcome of the 2008 events has helped to discredit war as a legitimate conflict resolution tool in the domestic discourse. Nonetheless, Georgia has adopted legislation that effectively prevents the elites of the de facto states of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from enjoying the privileges of statehood to the full extent.1

This, in turn, prompted Moscow’s controversial decision of 2008, representing a major shift away from the traditional anti-secessionist consensus of Russian foreign policy after 1991. Moreover, today Abkhazia and South Ossetia appear to be more dependent on Russia than they were prior to 2008, a situation reflected in how these entities are—or are not—“integrated” into contemporary conflict resolution efforts.2

Secondly, despite the fact that US interest in the region has been declining as the new US presidential administration remains mired in domestic turmoil, Russia still perceives the South Caucasus as a geopolitical and—considering the Association Agreement between the EU and Georgia—an increasingly geo-economic field of contestation. Hence, any Russian decision or policy proposal concerning Abkhazia and South Ossetia will necessarily be weighed against these geopolitical considerations and will, consequently, reflect the broader context in which Russia views the region.

Thirdly, the degree to which Russian policies vis-à-vis Abkhazia and South Ossetia represent an official legal position will inevitably have a potentially problematic impact on buttressing legal justification as well as legitimacy elsewhere: The resistance against an independent Kosovo seems, therefore, tenuous in the light of Russian policies in the South Caucasus.

In the following analysis, this three-tiered interplay will be examined by problematizing the conferral of citizenship and the assistance through “bilateral” agreements, which are separate but nonetheless intertwined issues. In particular, this contribution will investigate the repercussive backlashes these policies have had, and will have, for the Russian Federation and the breakaway states. The author will argue that the approaches chosen by the Russian Federation vis-à-vis the Georgian breakaway states are not strategically employed to interact with other official positions of the Kremlin.

“Passportization” or Standard Procedure in accordance with the Law?

With Putin’s rise to power –or even earlier, as some would argue– the Russian Federation gradually started to abandon its former role as a neutral broker3 in both conflicts. It seems that this shift was nowhere better visible than in the way that Russian citizenship was deliberately used as an instrument to fulfil Russia’s strategic interests in the early 2000s.4

An expansive character had always characterized the Russian citizenship law, though the reasons for this approach have varied over time.5 Technically, the law permitted simplified access to Russian citizenship even to former Soviet citizens not residing on the territory of the former Soviet Russia (RSFSR).6 In particular, the 2002 amendment to the law provided for the acquisition of Russian citizenship, through a simplified procedure, by stateless persons who were formerly Soviet citizens. That became the crux of the matter in Georgia: by virtue of this provision, hundreds of thousands of Abkhazians and Ossetians became eligible for Russian citizenship.

However, among all post-Soviet republics, only Latvia and Estonia produced significant numbers of de lege stateless persons following the adoption of their citizenship legislation. Unlike these states, Georgia and Moldova granted citizenship on a territorial basis. Hence, Abkhazians, Ossetians as well as other non-titular persons residing on Georgian territory were de lege Georgian citizens. Although it is evident that Abkhazians and Ossetians were not overly keen to obtain citizenship formally after the end of the 1990s wars, these individuals were not stateless. Likewise, even if these persons were not in physical possession of the piece of paper indicating their citizenship, they were still considered Georgian citizens de lege. In other words, Georgia cannot be held accountable for the effective—not legal—statelessness of these persons. However, the Russian authorities violated their own laws by inducing residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia to apply for Russian citizenship, supposedly in order to gain leverage both over the two entities as well as Georgia7.

Breach of Domestic Law as Repercussion

The first immediate repercussion for Russia resulting from this deliberately incorrect reading of the law affected the domestic principle of the rule of law in an area which has always been treated in a sensitive and cautious way. The breach of domestic Russian law was extensive. By conferring citizenship en masse, the Russian law enforcement agencies exposed their lack of ideological neutrality.

However, this excessive citizenship distribution over many years contributed to a change of policy by 2014. Among other factors, it arguably compelled the Russian State Duma to introduce new regulations on dual citizenship holders,8 obliging persons belonging to this group to notify the Russian Federal Migration Service of such citizenship if they resided outside of the Russian Federation.

Since their diplomatic recognition in 2008, the citizenship of the de facto states of Abkhazia and South Ossetia also fell under this category and indeed, the new 2014 regulation caused much concern in those entities. Once listed as holders of a second citizenship, these persons were effectively subjected to severe restrictions in their everyday civic opportunities: They are not eligible to work as public sector employees in Russia and face other limitations.

In addition to these domestic problems, the extension of citizenship also undermined Russia’s foreign policy. Both Putin and Medvedev publicly stated that the rationale for extending citizenship to the residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia was to protect Russian citizens from “genocide.” This rationale suddenly implied that the Russian Federation embraced the “responsibility to protect” doctrine supporting the idea of humanitarian intervention, something it had rigorously opposed in countless cases prior to the August 2008 war.

Ultimately, these domestic and foreign repercussive dimensions of the policy to confer citizenship on residents of the de facto states illustrate the dilemma that domestic rule of law and accountability can hardly be reconciled with geopolitical considerations.

“Bilateralized” Assistance

Abkhazia and South Ossetia seem unable to enter into relations with Russia as equals: both depend too strongly on Russia given their existence as unrecognized political entities by the rest of the world and the high level of their economic dependency. Thus, one may ask to what extent the Russian Federation seeks to organize its relations with both entities in a way that provides for a juridically separate existence in accordance with Moscow’s recognition of both entities as independent states?

Following the 2008 events, relations with both statelets and subsequent assistance provided by Russia had to be established through the baseline of a number of “bilateral” treaties.9 However, the degree to which this endeavor was achieved in a truly bilateral way seems dubious at best: With most of the territory budgets’ provided by Moscow and more than 90 percent of the residents possessing Russian citizenship, a real “bilateralism” could hardly be achieved from the very outset.

Once again, the citizenship issue provides a telling example: In accordance with Article 10 of the Agreement on Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance, the parties have the possibility to “protect the rights of their citizens living on the territory of the other contracting party”. Since the vast majority of the residents of Abkhazia and South Ossetia are Russian citizens, this provision effectively gives Russia a free hand to intervene into the internal affairs of these entities and would clearly undermine the logic of its underlying proposition.

Other subsequent agreements included explicit security guarantees and joint border management. However, the asymmetry of this endeavor was hard to deny. Development aid granted by some of those agreements serves as an ideal instrument to direct the overall economic development. Likewise, the agreement concluded in 2014 provides for the “creation of a common economic and social space.”

In other words, despite the bilateral activism of the past years, the disproportionate power of the Russian Federation became strongly evident, which in turn casts serious doubts on the assumption that Abkhazia and South Ossetia are in fact “independent political entities.” The bilateral agreements, rather than illustrating a somewhat equal relationship, reflect the enormous political and economic levers that the Russian Federation wields over Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Conclusion

The policies of the Russian Federation vis-à-vis Georgia’s separatist regions, particularly concerning citizenship and bilateral treaties, have revealed a lack of consistent legal and normative rationales in critical fields, arguably creating collateral damage for Russia itself. This damage affects both internal and external dimensions of state action: While the internal dimension exposes a selective implementation of domestic law, the external dimension reveals that the foreign policy of the Russian Federation concerning secessionist conflicts contributed to an incoherent, contradictory and unpredictable official legal rationale for the Kremlin’s actions in international affairs.

Notes

1 Georgia’s Law on Occupied Territories, adopted in 2008, bans all economic activities in Abkhazia and South Ossetia by all domestic and foreign companies. Further, it also prohibits foreign citizens to travel to Abkhazia and South Ossetia without authorization by the Georgian authorities. In addition, the US and a number of European countries view Russia as a military occupying power in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Therefore, Georgia has scored a major success in how these two breakaway territories are perceived today.

2 In the Geneva talks, the official delegations are allowed to invite so-called “guests” to the discussions. Hence, Abkhaz and Ossetians participate only in this capacity, and in unofficial working groups on IDPs and security. Yet, they remain excluded from the plenary sessions. See: Nona Mikhelidze, “The Geneva Talks over Georgia’s Territorial Conflicts: Achievements and Challenges”, Documenti IAI 10, 25 November 2010, 1–7, 3, <http://www. iai.it/sites/default/files/iai1025.pdf>

3 Russia was indeed, a broker and guarantor of a number of ceasefire agreements concluded between Georgia and the breakaway states, e.g. the Moscow Agreement concerning Abkhazia of 1994.

4 Applications for Russian citizenship from Abkhazia and South Ossetia reached their peak between 2002 and 2003, something which the Russian authorities also actively supported. See: Osipovich, A. (2008) ‘Controversial Passport Policy Led Russians into Georgia: Analysts’, AFP, 21 August.

5 It has to be noted that this flexible approach was also chosen to avoid mass immigration into Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

6 For instance, provided that they simply registered within three years after the law’s adoption. See, in particular, the first draft of the citizenship law of 1991, Federal Law No. 1948-1-FZ of November 28, 1991).

7 Franziska Smolnik, Secessionist Rule: Protracted Conflict and Configurations of Non-state Authority (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2016), 132.

8 Without a doubt, addressing the taxing dilemma of Russian expatriates was an additional objective of this regulation.

9 Between 2009 and 2014, the Russian Federation signed over 70 agreements with South Ossetia and Abkhazia on different issues relating to military and economic cooperation as well as border management. See: Thomas Ambrosio and William Lange, “The architecture of annexation? Russia’s bilateral agreements with South Ossetia and Abkhazia”, Nationalities Papers (44:5, 2016), 673–693, 680.

About the Author

Benedikt Harzl is Assistant Professor at the Russian East European Eurasian Studies Center (REEES) at the Law School of the University of Graz and an Austrian Marshall Plan Foundation Fellow in Central European Studies at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies.

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.