Russian Analytical Digest No 220: Political Economy

28 May 2018

By Anders Åslund for Center for Security Studies (CSS)

The article featured here was originally published by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) in the Russian Analytical Digest on 16 May 2018. Thumbnail image "external pageПетергофcall_made" courtesy of Dmitry Dzhus/Flickr. Image license external page(CC BY 2.0)call_made.

Russia’s Economy: Macroeconomic Stability But Minimal Growth

By Anders Åslund

Two Contradictory Narratives

Any discussion about Russia’s economy tends to lead to a division into two camps. One camp, which includes President Vladimir Putin, claims that the situation is good because Russia enjoys solid macroeconomic stability and eventually growth is to come.

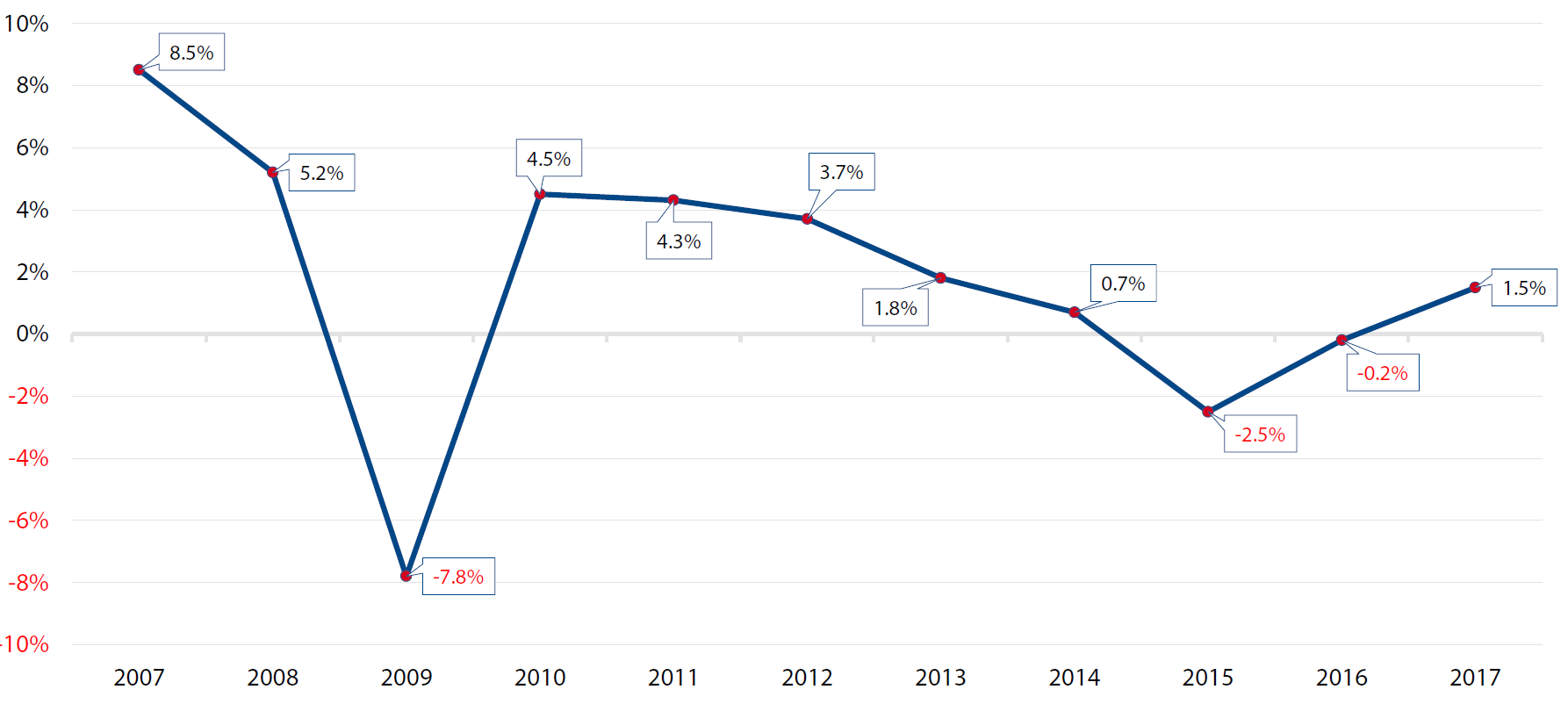

The other camp, including many Russian liberals and Westerners, focuses on the low growth rates. While Russia has managed to go through the repeated financial crises of 2008–9 and 2014–15 with reasonable macroeconomic stability, its economic growth shows no sign of rising above a meager 1.5–2.0 percent a year, a range within which virtually all serious forecasts fall.

It is time to put an end to this discussion. Russia’s macroeconomic policy has been close to stellar since 1999, while little structural reform has taken place after 2005. Rather than proceeding, structural changes are regressive. The standard of living fell for the four years 2014–17. Higher economic growth appears unlikely and that is a serious concern because the generation of economic welfare is the ultimate aim of economic policy.

Impressive Macroeconomic Stability

Russia’s financial crash of 1998 was a pivotal moment. On August 17, 1998, the Russian government defaulted on its domestic debt of $70 billion, froze international bank payments for three months, and soon devalued the ruble to one-quarter of its dollar value. Half of Russia’s commercial banks went under, including nine of the ten biggest oligarchic banks. The government of Sergey Kirienko fell.

For Vladimir Putin, who had just become FSB Chairman and was to be appointed prime minister in August 1999, this was a learning moment. His key lesson was that financial instability must be avoided at any price, because it could cost him political power. Ever since, Putin has emphasized the virtues of a conservative financial policy. This honor is rightly given to Aleksey Kudrin, who was his finance minister from 2000 until September 2011 and his team of likeminded fiscal conservatives. However, Putin appointed them all and they served at his pleasure. Putin had chosen strict fiscal conservatism, which he clearly sees as a precondition for true national sovereignty.

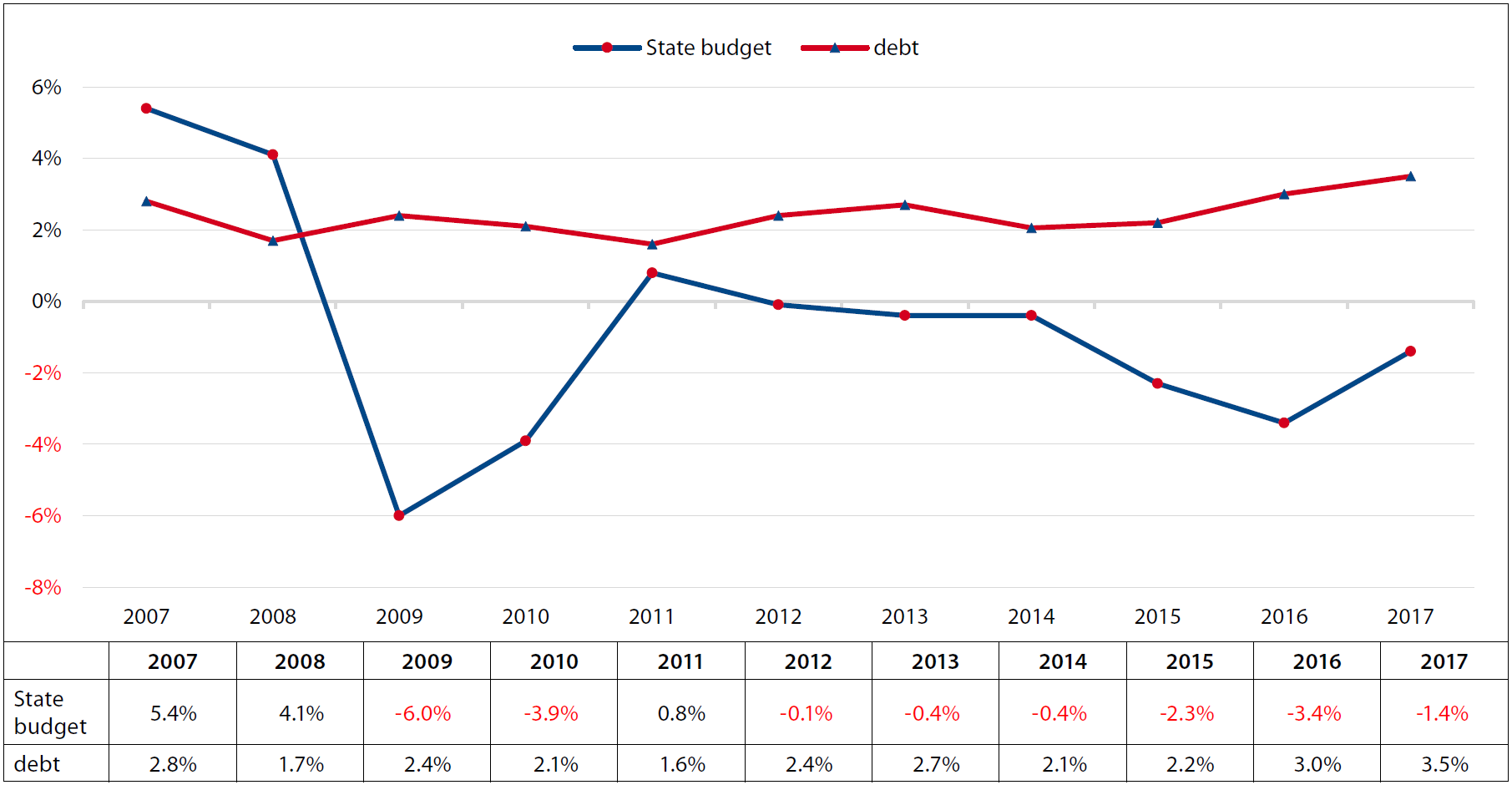

This fiscal conservatism is evident in all policies, and Putin himself mentions several of them in each public speech. The big lesson from 1998 was that Russia could no longer have a big budget deficit. At that time, nobody was prepared to lend Russia money, and the government could not swiftly raise revenues. The only way out was to cut expenditures sharply, and the governments did so by 14 percent of GDP from 1997 to 2000. As a consequence, from 2000 until 2008, Russia has sizable budget surpluses. Another outcome was that the public debt that equaled GDP in 1999 slumped to as little as 5.4 percent of GDP in 2008.1

Not only the government but also the country as a whole has had a steady and usually big foreign surplus on its current account. The Central Bank of Russia built up the third biggest currency and gold reserves in the world after China and Japan. They peaked at nearly $600 billion in August 2008, but they have stayed impressive. At present, they are about $450 billion.

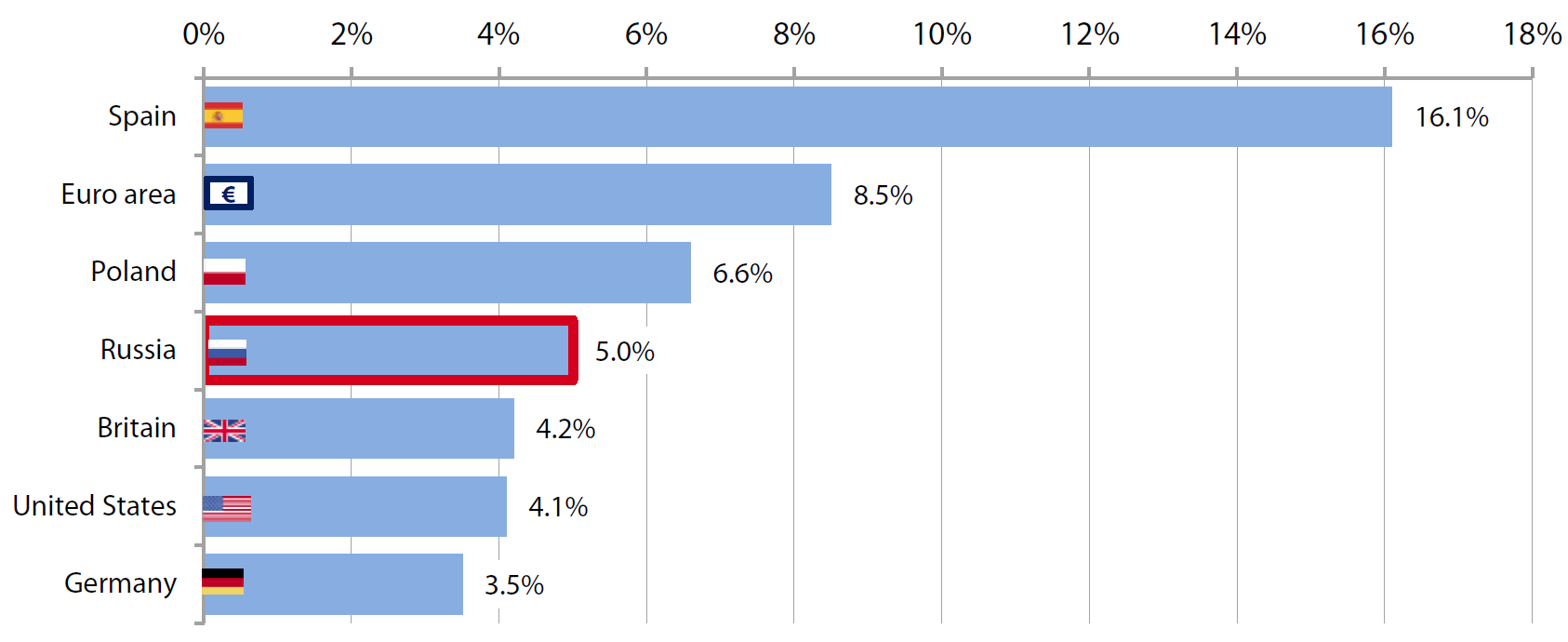

Macroeconomic measures that concern the population more directly have been given somewhat less attention, but inflation has now been pushed down to as low as 2.2 percent a year. Unemployment has been low all along, currently just over 5 percent of the labor force.

Much attention has been devoted to the crisis resolution of the Russian government in response to the global financial crisis in 2008–9 and the halving of the oil price and the imposition of Western sanctions in 2014–15. Officially, the government has claimed that it pursued the same policies, but they have in fact been quite different.

In 2008, the main government response was a huge fiscal stimulus. The budget balance swung from a surplus of 4 percent of GDP in 2008 to a deficit of 6 percent of GDP in 2009. Although Russia had the largest fiscal stimulus of any G-20 country, it also had the largest output decline of nearly 8 percent.

The explanation may lie in Russia’s bailing out of big state and oligarchic companies that crowded out other, more competitive and agile firms. A related reason was that Russia carried out a very gradual devaluation during three months in the winter of 2008–9, which in effect allowed the rich and powerful to speculate against the ruble and make a fortune on their overvalued rubles. As a result, Russia’s currency reserves shrank by $200 billion.

In 2014, the Russian government did not possess as large resources as in 2008, and the future looked less secure. Therefore, it adopted quite a different crisis resolution. The main action was to let the ruble float freely from December 2014. Initially, the ruble plummeted, causing a short-lasting panic and a sudden rise in inflation. This time, the government did not opt for any big fiscal stimulus, but pursued strict fiscal and monetary policies that contained the fall of the ruble, while inflation gradually fell to new lows. The currency reserves took a big hit in 2014, but started recovering in 2015. Since 2016, all macroeconomic indicators have looked just fine to the great pride of President Putin.

Meager Economic Growth

But you cannot eat macroeconomic stability. The key measures for the standard of living are the growth of the economy and real incomes. Russia experienced a wonderful decade of high economic growth from 1999–2008 with an average annual growth of no less than 7 percent.

In the early fall of 2008, Russia was at its peak. Putin even spoke of Russia as a safe haven in a world of financial crisis, but then it hit the country hard, and since 2009 Russia has had an average annual economic growth of no more than 1 percent.

For years, Putin blamed the global financial crisis and the low growth on the West, but economic growth has not recovered as it has done so globally. Clearly, Russia suffered from specific problems. While the crash of 1998 kick-started the economy, the crisis management of 2008 led to a much lower growth rate.

One big difference was that in 1998, the basis of a market economy had been laid and ample free capacity was at hand. The economy was ready for a take off. In addition, the old inept state enterprise managers were swept away by a wave of bankruptcies. In 2008 and 2014, the opposite happened. The government bailed out the incumbent owners and managers regardless of their performance. Rather than stimulating renewal and competition, the government did the opposite. A natural consequence was slower economic growth.

During Putin’s first term, 2000–4, his administration carried out a large number of substantial reforms, such as tax reform, pension reform, judicial reform, administrative reforms, as well as the adoption of a civil code. This was Russia’s greatest reform period. Its economic system was at its best in 2003. The newly privatized oil sector, Yukos, Sibneft and TNK-BP, drove the economic growth from 1999–2004, increasing Russia’s oil production by 50 percent by blowing new life into Russia’s brown fields.

However, after the oil prices started rising from the fall of 2003 further structural reforms seemed superfluous. Moreover, the low-hanging fruit of easy and popular reforms, such as the tax and land reforms, had already been undertaken, while the heavy social reforms remained. The monetization of social benefit in January 2005 was the last reform of significance. It aroused great popular protests among old-age pensioners. Putin did not seem convinced of the usefulness of further reforms, and he was not keen on facing protests.

The big negative turning point in Russia’s economic policy was the arrest of the main owner of the Yukos oil company, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, and the ensuing confiscation of Yukos’ property. The affair put an end to many things. Russia’s road toward more democracy and freedom finished; the affair showed the limits of the judicial reforms and property rights; it started a steady stream of renationalizations of successful private companies, ending the reign of oligarchs; and, ultimately, it marked the end of market economic reforms. Yet, to many people this became evident only much later.

Putin’s second term, 2004–8, was characterized by state capitalism. He merged hundreds of state and private companies into vast state holding companies. Gone was the idea of competition. His third informal term, 2008–12, when Putin was prime minister, became a time of blatant theft by his old St. Petersburg business friends.

Both the state companies and his cronies seemed insatiable, indulging in ever cruder asset stripping, impeding new enterprise development. The founder of Russia’s Facebook competitor vKontakte, Pavel Durov, had to flee the country when he refused to give information about his subscribers. Yevgeny Chichvarkin, who set up thousands of mobile phone shops, was raided and forced out of Russia. Even the patently obedient Vladimir Yevtshenkov was deprived of the oil company Bashneft after he had successfully restructured it.

Since 1991, Russia had pursued a clear course toward ever freer foreign trade, but in 2009 Putin decided to opt for a limited customs union with a few post-Soviet countries instead, stopping this trend. The Eurasian Economic Union with Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan has not raised the standard of living of anybody, while causing Russia large costs and much chagrin from everybody concerned.

As if to compensate for the minimal economic growth and the poor and declining standard of living, the Kremlin has opted for small wars. In August 2008, it pursued a five-day war in Georgia, which aroused great popularity. In February–March 2014, Russia occupied and annexed Crimea from Ukraine. It was wildly popular in Russia and the direct cost was limited, but the West responded with substantial primarily financial sanctions. Their greatest effect might have been that they further aggravated Russia’s trend toward clientelism and protectionism.

Further Russian aggression in eastern Ukraine and through cyber warfare have alienated the United States, the European Union, and all former Soviet republics. Russia is becoming increasingly lonely and isolated. Naturally, foreign direct investment in Russia has fallen sharply. Rather than facing up to realty and mitigate the damage he has caused, Putin just escalates, for example, by punishing his people with prohibitions against food imports from the West, causing further damage to Russia’s economy. At the same time, the Russian economy appears to go through an increasing criminalization at the very top.

This kind of economy is not likely to grow much. Investment is kept low by continued capital flight and the scaring away of foreign direct investment. Promising entrepreneurs tend to emigrate because of the hostile business climate. Research and development is not being integrated into the world but is being cut off or even punished for undue liberalism. The labor force is set to decline by 0.7 percent a year for the next fifteen years for natural reasons. Five state banks account for 60 percent of all banking assets, and they favor the big state and oligarchic companies. In the second half of 2017, three of the five biggest privately owned Russian banks went under amidst allegations of major fraud. However high the oil price may rise, it is difficult to see how this economy can grow by more than at most 2 percent a year.

The single hope is economic reforms. Russia maintains a sound, open economic discussion, including the reformers from the 1990s with Kudrin in the lead, but the economic system that Putin has built does not appear possible to reform. Even if Putin would so desire, he is surrounded by three strong constituencies that are likely to oppose any serious reforms. The State Security Service (FSB) would hardly accept to be constrained by any courts. The state enterprise managers oppose any real privatization. And Putin’s cronies seem insatiable in their personal enrichment.

Note

1 The macroeconomic statistics here are taken from Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition, BOFIT, Russia Statistics, <https://www.bofit.fi/en/monitoring/statistics/russia-statistics/> accessed on April 25, 2018.

About the Author

Anders Åslund is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and is writing a book about Russia’s crony capitalism.

Russia: Main Macro-Economic Indicators

Real Economy

Figure 1: GDP (Change to Previous Year)

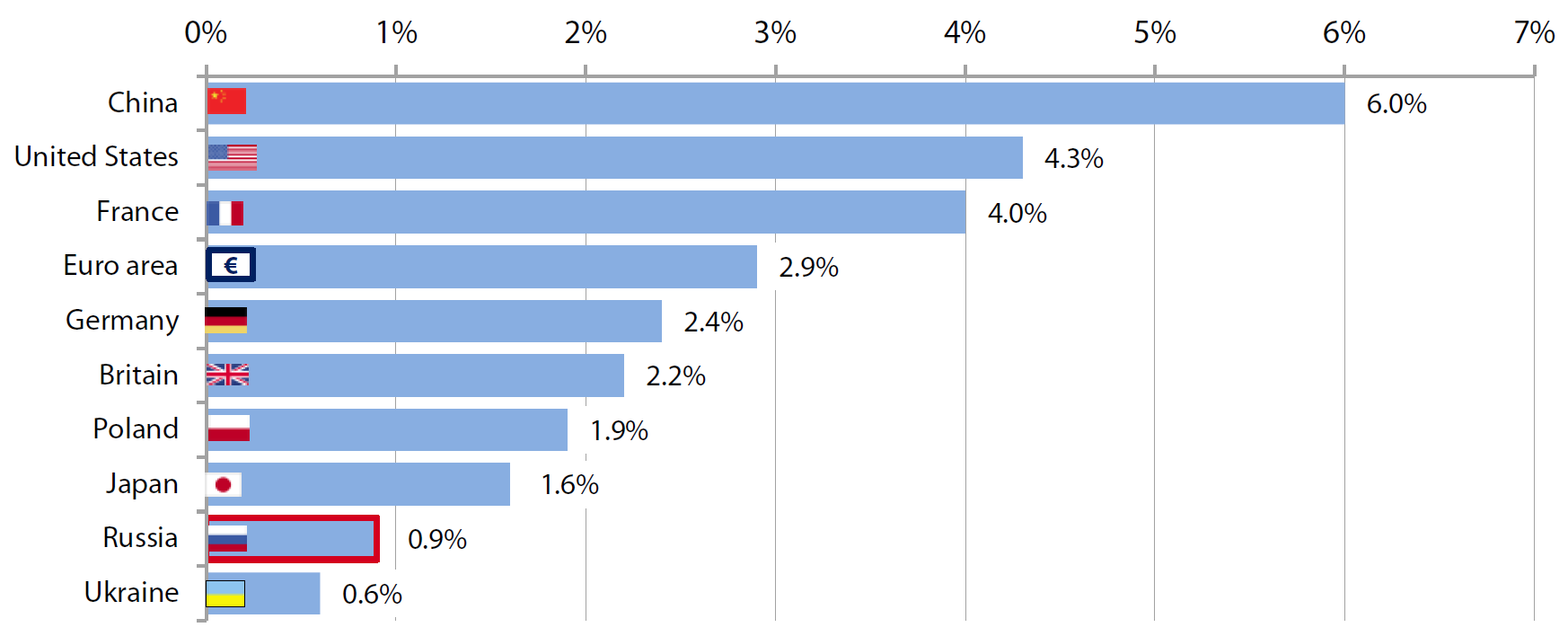

Figure 2: Industrial Production (Latest Figure, February or March 2018) (% Change on Year Ago)

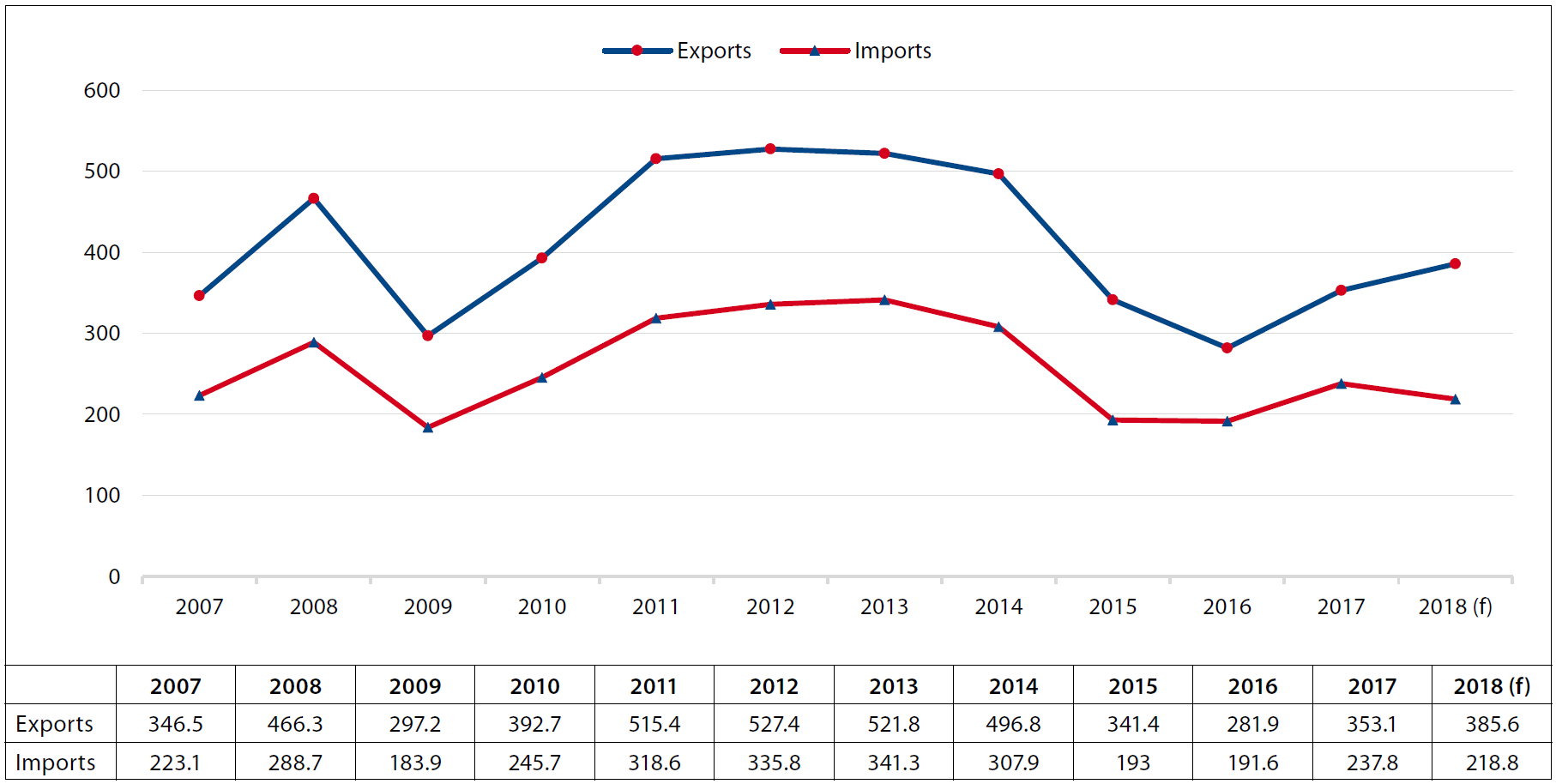

Figure 3: Foreign Trade (USD Bln.)

Finances

Figure 4: Balance of State Budget and External Debt (Federal Government Only, as Share of GDP)

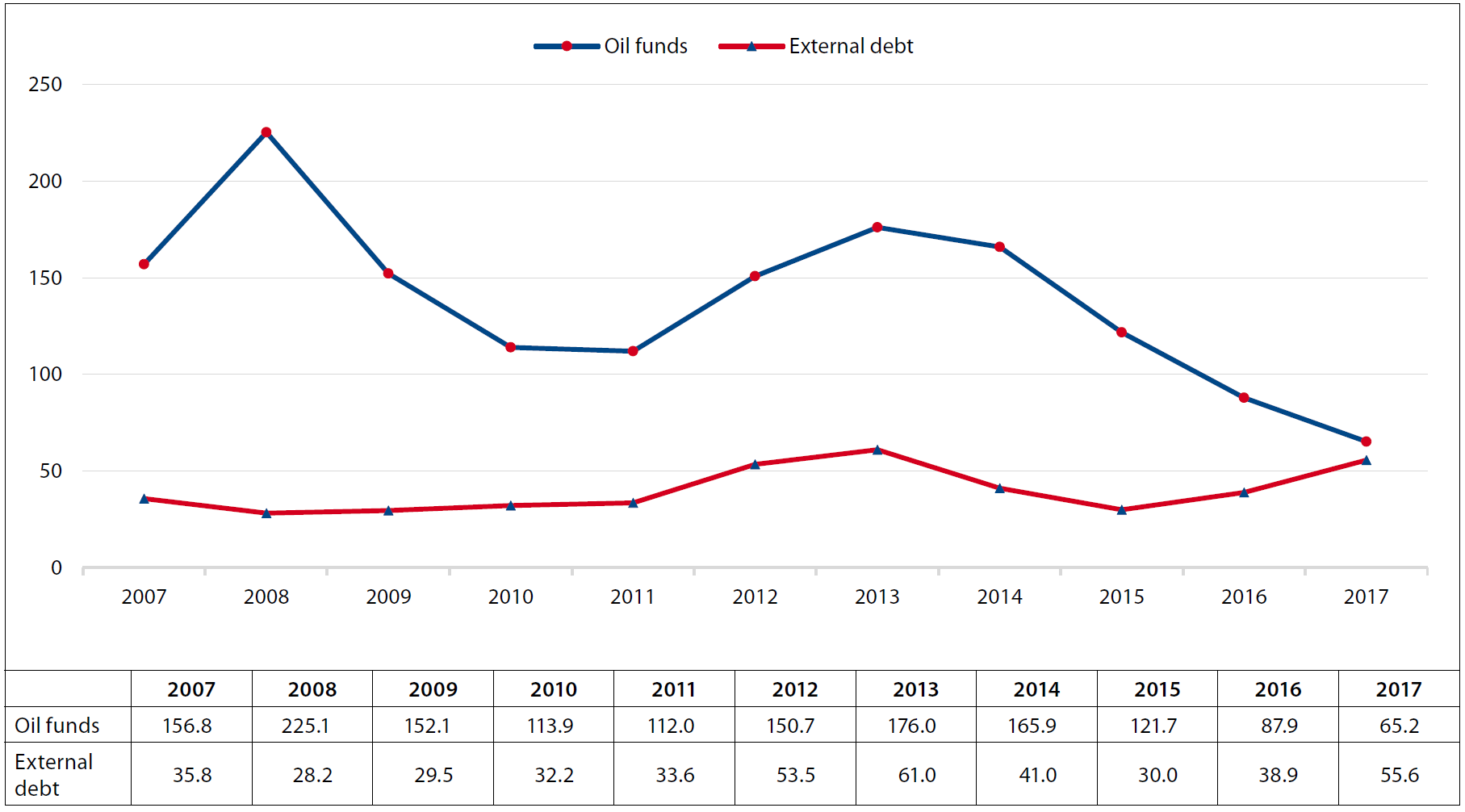

Figure 5: External Debt and Value of State Oil Funds (in Bln USD)

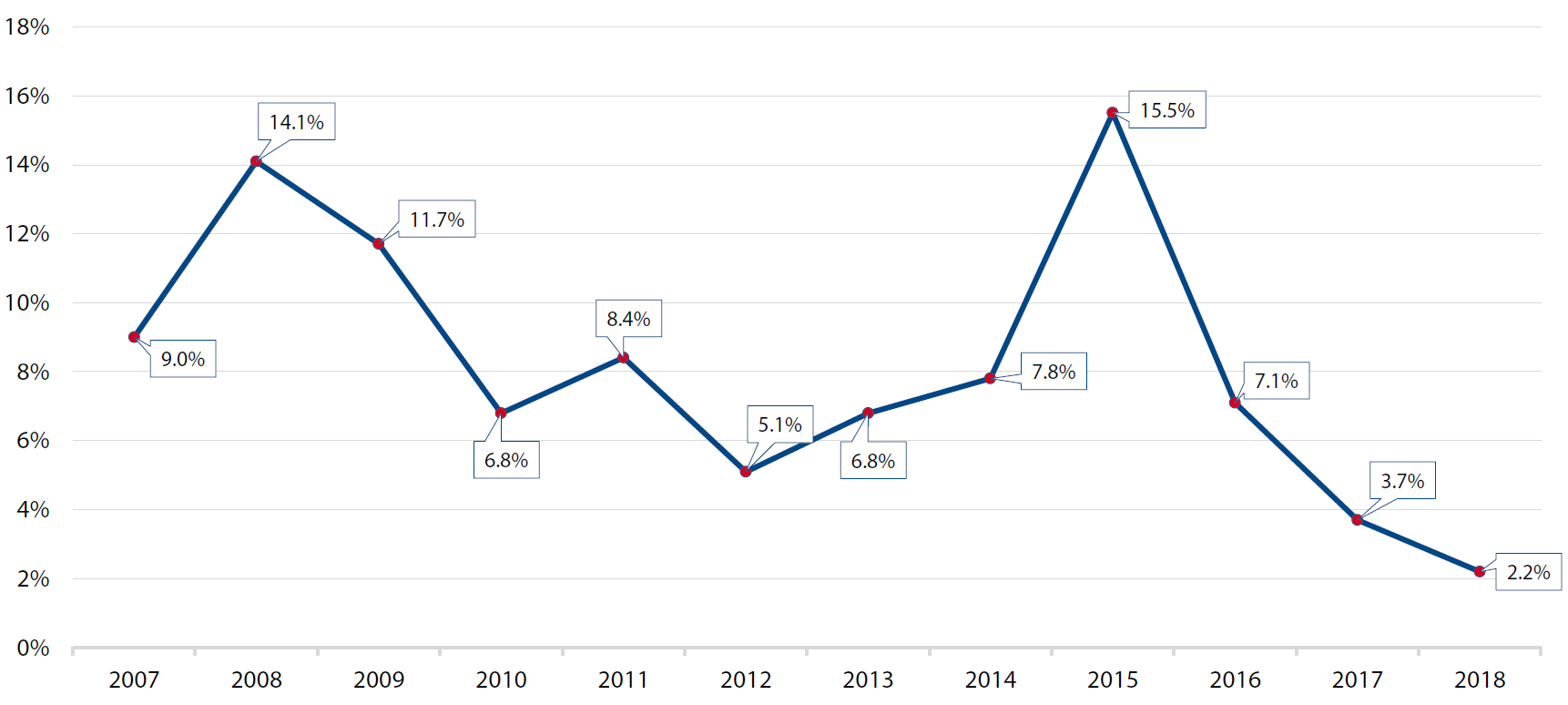

Figure 6: Consumer Price Inflation

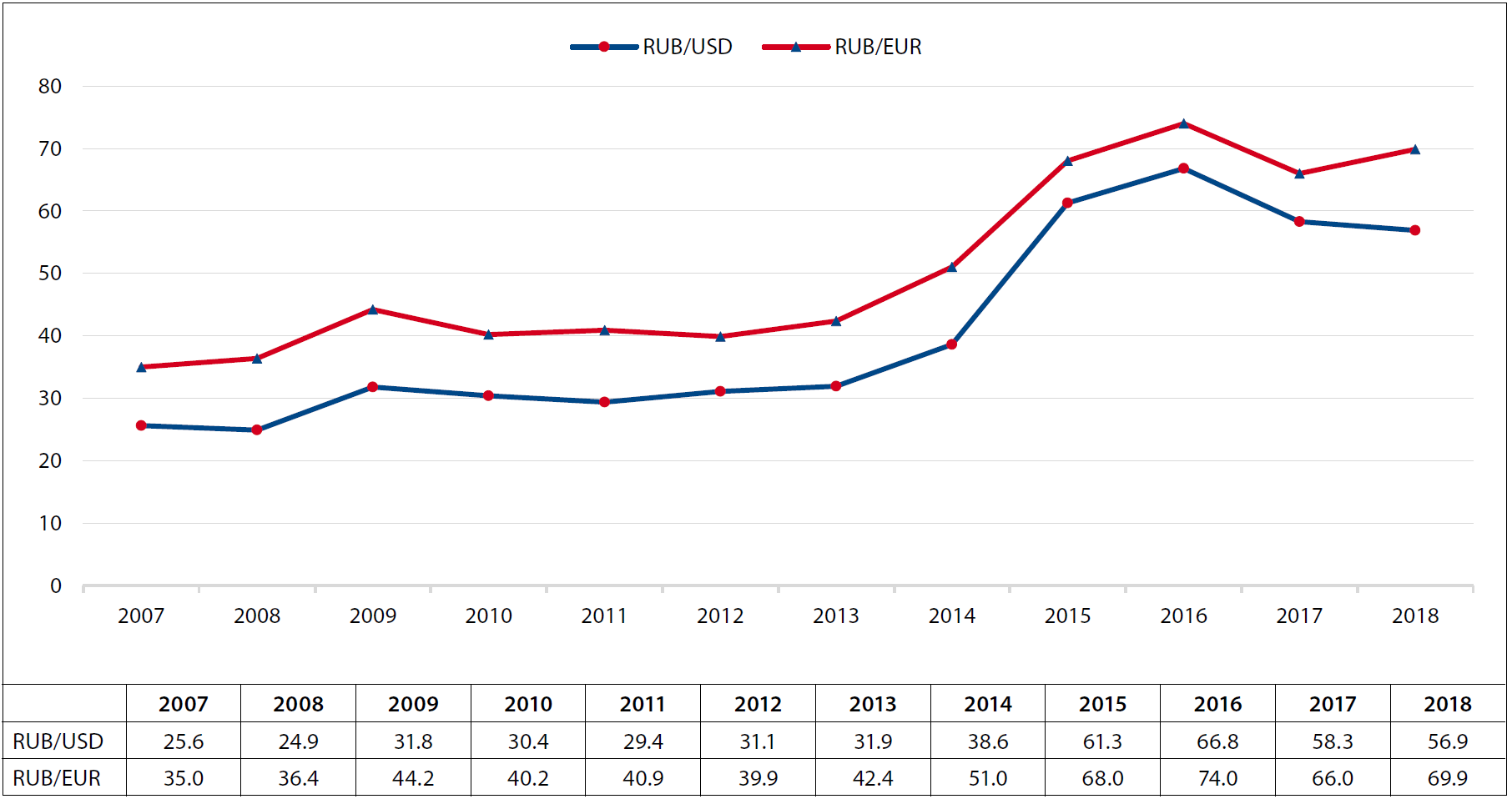

Figure 7: Exchange Rate

Social Data

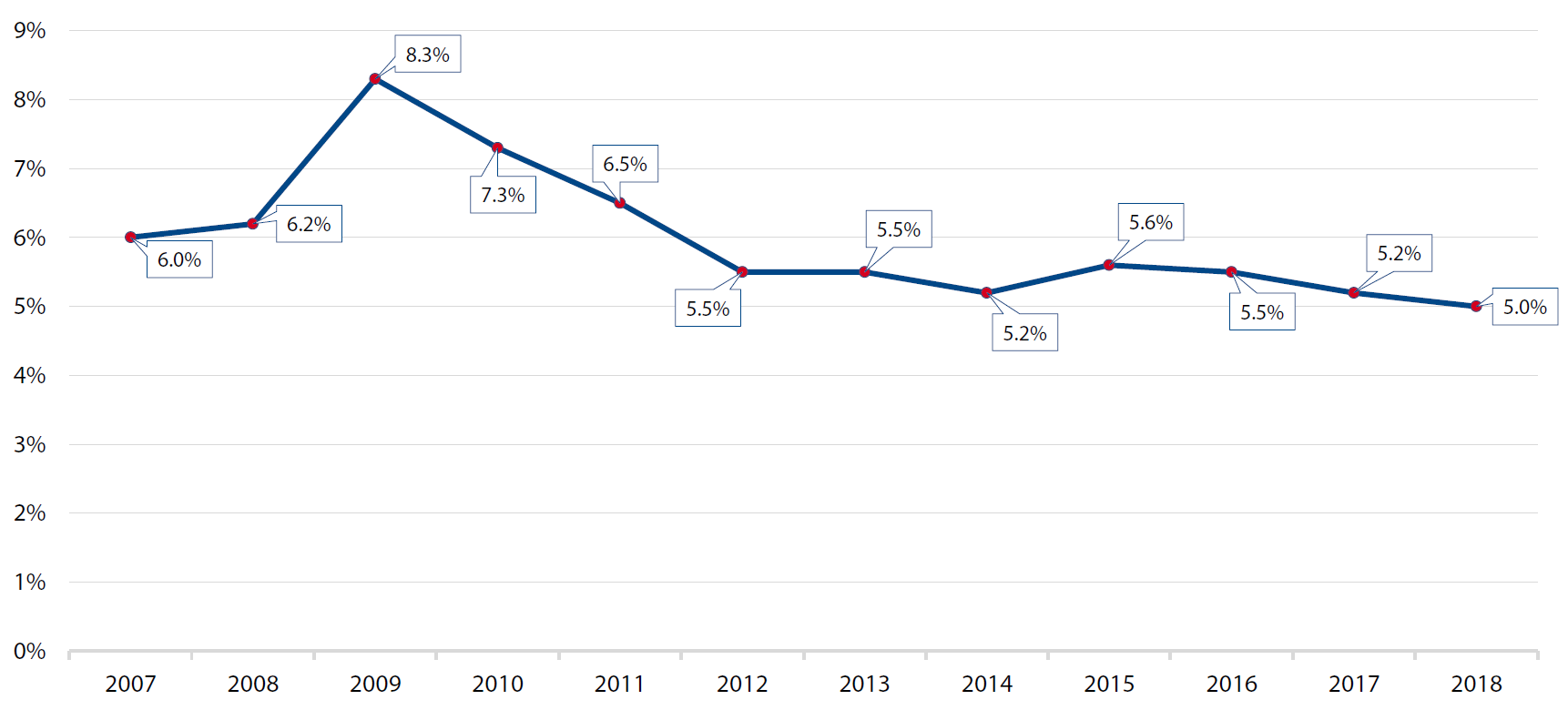

Figure 8: Unemployment Rate (ILO Method)

Figure 9: Unemployment Rate (Latest Figure, February or March 2018)

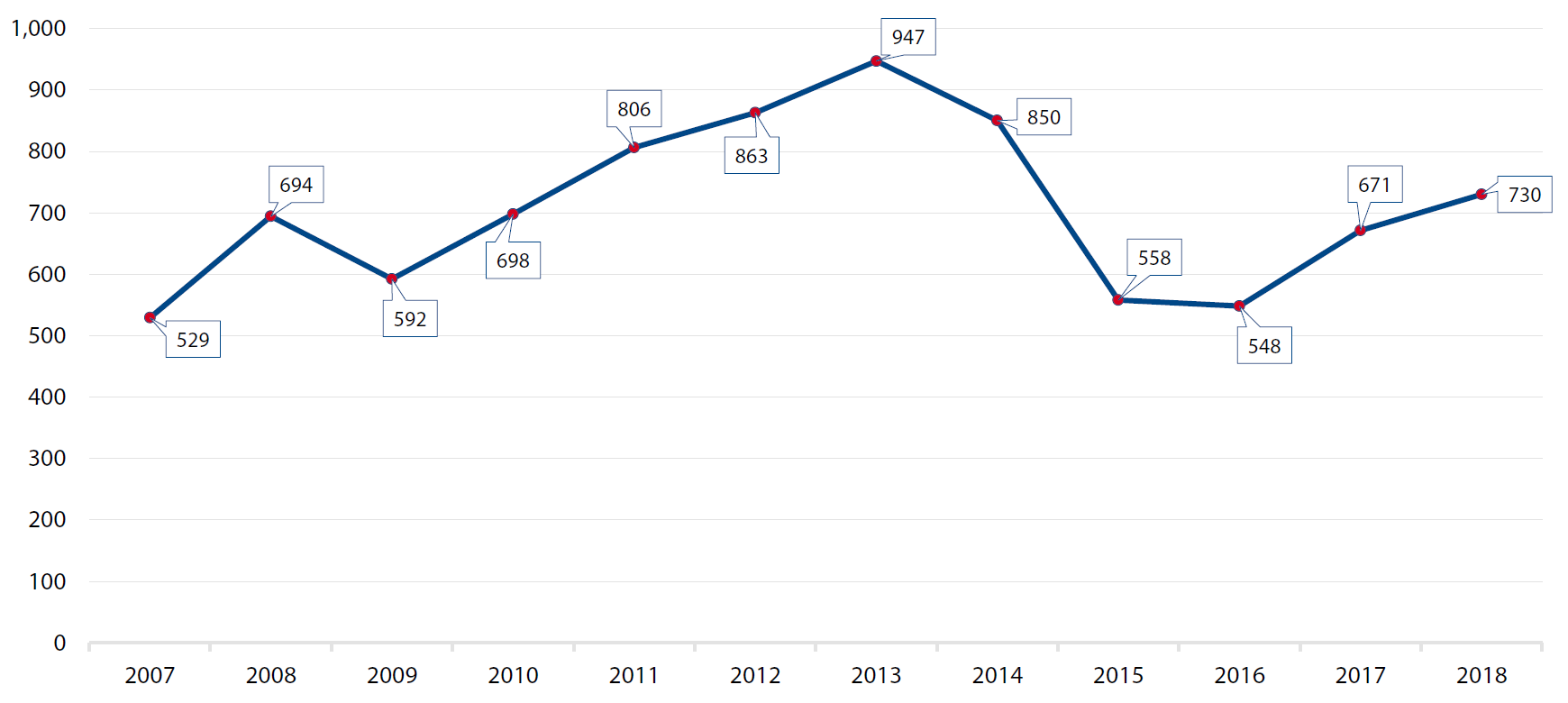

Figure 10: Average Monthly Wage (Converted into USD)

For more information on issues and events that shape our world, please visit the CSS Blog Network or browse our Digital Library.